Abstract

The guidelines for the management of hypertension by the Japanese Society of Hypertension (JSH2019) defined blood pressure (BP) levels of 130–139/80–89 mmHg as “elevated blood pressure”. The JSH2019 also revised the target level of BP control to a lower level. Thus, lifestyle modifications are quite important regardless of the use of antihypertensive drugs. Among the lifestyle modifications, salt reduction is most important, especially among East Asian people, who still consume a significant amount of salt. Since the awareness of salt reduction may not necessarily lead to actual salt reduction, the assessment of individual salt intake is essential when members of the medical staff provide practical guidance regarding salt reduction. The evaluation methods of salt intake are classified as the assessment of dietary contents and the measurement of urinary sodium (Na) excretion. Since highly reliable methods, such as the measurement of 24-h urinary Na excretion, are not convenient in practical clinical settings, the combination of the assessment of dietary contents using questionnaires and the estimation of salt intake using spot urine is recommended as a practical evaluation procedure. Repeated assessment of salt intake and practical guidance from dieticians are useful for long-term adherence to salt reduction. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Salt Reduction Committee began to certify flavorful foods as being low in salt content in 2013. More than 200 products have been certified as of April 2019. The utilization of these products is expected to aid in the salt reduction of hypertensive individuals as well as the Japanese general population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of hypertensive individuals in Japan is estimated to be 43 million. The Japanese Society of Hypertension (JSH) revised the Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension 2014 (JSH2014) and published the JSH2019 [1]. In these guidelines, a BP level of ≥140/90 mmHg is adopted as the criterion for grade I or higher hypertension, while the subclasses “normal blood pressure” and “high-normal blood pressure” employed in the JSH2014 are classified and expressed as “high-normal blood pressure” (120–129 and <80 mmHg) and “elevated blood pressure” (130–139 and/or 80–89 mmHg), respectively. Lifestyle modifications should be attempted by all individuals with a BP level of≥ 120/80 mmHg. In high-risk individuals with “elevated blood pressure” and in patients with hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg), lifestyle modifications/nonpharmacological therapy should be performed actively, and antihypertensive treatment should be initiated as needed. Since the target levels of BP control are also revised to the lower levels compared with those of the JSH2014, the importance of lifestyle modification is emphasized regardless of antihypertensive treatment.

Excessive salt intake is one possible cause of the high prevalence of hypertension and stroke in Japan. Numerous observational or interventional studies have demonstrated that BP is high in groups with high salt intake and that BP decreases following reduced salt intake [2,3,4]. Thus, salt reduction is the most important factor for guidance regarding lifestyle modification in Japanese hypertensive patients.

This review focuses on the current status of salt intake and discusses the practical and personal education of dietary therapy in Japanese hypertensive patients.

Lifestyle modification recommended by the guidelines

Table 1 indicates the points of lifestyle modification advocated by the JSH2019 [1]. The degree of BP reduction achieved by the modification of individual factors is not always large, but comprehensive modifications are more effective. Multidisciplinary guidance, including guidance by dieticians and physical therapists, is necessary. Because salt reduction with a goal set at <6 g/day is expected to be effective in reducing BP and suppressing cardiovascular events, the JSH2019 adopts the salt reduction goal of <6 g/day. In a meta-analysis of 8 interventional studies of hypertensive populations, including prehypertension cases, analysis was conducted by dividing the salt intake level into four categories: low (<5.3 g/day), relatively low (5.3–9.2 g/day), relatively high (9.3–14.5 g/day), and high (>14.5 g/day) [5]. In that analysis, BP showed a dose-dependent change, with a 6.87/3.61 mmHg reduction recorded following salt reduction to 4.5–8.2 g/day. In addition, in other meta-analyses, effectiveness in lowering BP was shown following salt reduction to less than 6 g/day [6, 7]. On the basis of these reports, the Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension in Adults prepared by the Evidence Analysis Library® (USA) proposed that a reduction in salt intake to 3.8–5.1 g/day lowers BP by 12/6 mmHg at maximum [8]. Thus, a salt reduction goal of <6 g/day for hypertensive patients is supported by adequate evidence.

Salt intake and cardiovascular events

A salt reduction goal of <6 g/day is expected to suppress the onset of or death from cardiovascular events by hypotensive effects, but no long-term interventional study evaluating the direct relationship between salt intake level and cardiovascular events, cardiovascular death or total death has been reported. In the combined analysis of the data from four studies, including the PURE study based on the values estimated from a single spot urine sample, a J-shaped relationship was observed between the salt intake level and cardiovascular events and total death, and a significant increase in combined primary endpoints (total death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure) was noted in the group with an Na intake of less than 3 g/day (equivalent to ~7.6 g salt/day) compared with the group with an Na intake of 4–5 g/day (equivalent to 10.2–12.7 g salt/day) [9]. On the other hand, a linear relationship was noted between salt intake levels (evaluated using 24-h pooled urine samples 3–7 times during an interventional study lasting for 1.5–4 years) and total death during the follow-up period (23–26 years) among prehypertensive cases [10]. One possible factor resulting in such contradictory results in observational studies is the large bias in the low value range or the high value range of urinary salt excretion determined by the Kawasaki method using spot urine samples (employed in the PURE study) or the possibility of so-called “reverse causation” in observational studies based on single measurements [11, 12]. In a recently reported prospective cohort study in China, salt intake was evaluated via the collection of overnight urine from 954 residents for three consecutive days during two seasons. As a result, cardiovascular events and stroke incidence during a median follow-up period of 18.6 years were significantly higher in subjects with high salt intake [13]. This observation also supports the conclusion that high salt intake, as evaluated by multiple measurements of salt intake, is associated with a high incidence of cardiovascular events. Because there is no long-term interventional study using salt intake levels evaluated with 24-h pooled urine, the evidence is not adequate to address the relationship between salt intake levels and the suppression of cardiovascular events. However, sufficient evidence indicates that salt reduction to <6 g/day is effective in lowering BP in hypertensive patients. Therefore, it is recommended to adopt the salt reduction goal of <6 g/day because it is expected to suppress the onset of cardiovascular events as well as cardiovascular death by hypotensive effects.

Regarding the goal of salt reduction, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension Treatment Guidelines 2017 presented a goal of 1500 mg Na/day (equivalent to 3.8 g salt/day), stating that even when this goal is not achieved, BP may be reduced if the daily Na intake is reduced by at least 1000 mg (equivalent to 2.5 g salt) [14]. On the other hand, the European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension Hypertension Treatment Guidelines 2018 proposed a goal of reducing salt intake to <5 g/day [15], and the WHO Guidelines (for the general population) strongly recommended a salt intake of less than 5 g per day [16].

Potassium intake and other dietary patterns

The increased intake of potassium is another important point of dietary therapy. Because potassium antagonizes the hypertensive effects of sodium, the intake of potassium-rich foods, such as vegetables and fruits, is expected to exert hypotensive effects. In a meta-analysis of 23 studies involving a total of 1213 hypertensive patients and focusing on the relationship between potassium intake and BP, BP reduction following potassium supplementation (4.25/2.53 mmHg on average) was significant, and a dose–response relationship was noted between potassium intake (<50 mmol/day, 50–99 mmol/day, ≥100 mmol/day) and the magnitude of BP reduction [17]. In another meta-analysis focusing on the relationship between potassium intake and stroke, the risk for stroke was lowest when the potassium intake was 90 mmol ~3500 mg)/day [18]. The WHO recommends at least a 90-mmol/day potassium intake for the purpose of reducing BP and suppressing the risk for cardiovascular diseases [16]. With respect to potassium intake in the Japanese population (age 20 and over), the National Health and Nutrition Survey in 2017 reported 2,382 mg for men and 2256 mg for women [19]. Given the target for daily potassium intake (3000 mg or more) proposed in the “Dietary Nutrient Intake Standards for Japanese 2015” (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) [20], greater potassium intake is recommended. In Japan, where salt intake is high but potassium intake is low, we may consider it important to recommend salt reduction plus a greater intake of potassium. Reports are available on the hypotensive efficacy of dietary patterns rather than of individual nutrients taken from foods. Among these reports, sufficient evidence has been reported on the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, which is rich in vegetables, fruits and low-fat dairy products and low in saturated fatty acids and cholesterol, and its combination with salt-reduction programs (DASH-sodium diet) [21, 22]. In addition, hypotensive efficacy has been reported with dietary patterns rich in olive oil and polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as the Mediterranean diet and Nordic diet, as well as dietary styles rich in seafood, grains, vegetables, fruits and beans, and low in meat [23]. The traditional Japanese dietary pattern is close to these dietary patterns and will facilitate a healthy diet if combined with a salt-reduction program.

Assessment of salt intake in hypertensive individuals

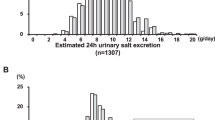

Awareness of the necessity of salt reduction among hypertensive patients has not always led to corresponding daily practices (Fig. 1) [24], and it is therefore important to assess salt intake levels in individual patients when guiding them towards salt reduction. Table 2 shows the method of the evaluation of salt intake levels [25]. The assessment based on dietary contents includes the weighing method, the questionnaire method and the measurement-before-intake method. The weighing method, by which salt intake is estimated by weighing the food ingested by each subject, is highly reliable but is complicated and requires calculation by a dietician. The questionnaire method is easier than the weighing method, but it still requires calculation by a dietician. The measurement-before-intake method is highly reliable, and hospital meals and test meals for clinical research are examined by this method. However, it is inconvenient to measure the salt content before each meal, and accurate determination requires calculation by a dietician. The measurement of urinary Na excretion is an alternative method for the evaluation of salt intake. It includes the measurement by 24-h urine collection, measurement by nighttime or overnight urine collection and measurement by using second morning urine or spot urine samples. The measurement by 24-h urine collection is the gold standard for assessing salt intake and is thus used in many clinical and epidemiological studies. However, it is relatively difficult to perform, and inadequate urine collection may lead to the underestimation of salt intake. The measurement by nighttime or overnight urine is more convenient than 24-h urine collection. A urine salt sensor, which estimates salt intake by analyzing data in overnight urine using a preinstalled calculation formula, has been reported to be in relatively close agreement with the value determined by 24-h urine collection [26]. The usefulness of the self-monitoring of daily salt intake using this device for salt reduction was reported in hypertensive patients [27] as well as in the general population [28]. The estimation of salt intake by measuring Na in the second morning urine sample [29] or spot urine sample [30] is used in epidemiological studies. Although the values obtained by these methods are not highly reliable, they are nonetheless convenient and considered clinically useful. In clinical practice and at health checkup facilities, it is recommended to evaluate the daily urinary salt excretion estimated from the urinary Na levels of spot urine and to propose a feasible method of salt reduction with the use of a simple questionnaire, such as a food intake frequency questionnaire. However, because the estimate based on a spot urine sample is not highly reliable, it is necessary to repeat measurements while providing guidance to individuals and to judge the efficacy by evaluating a trend.

Distribution of 24-h urinary salt excretion in salt-conscious (n = 271) and non-salt-conscious (n = 89) hypertensive patients [24]

Practical and personal education of dietary therapy

The food items contributing salt intake are diverse among individuals in Japan [31]. Thus, it is essential to provide specific and practical guidance regarding salt reduction based on the subject’s eating habits. We have developed the “salt check sheet”, which evaluates the sources of salt intake by asking 13 brief questions. These questions are categorized as follows: seven items evaluate the intake of salty meals such as miso soup, pickles and noodles; four items evaluate the use of salty sauces such as soy sauce and the frequency of eating out and the use of home-meal replacements; and the remaining two items evaluate the seasoning content and the amount of food. This check sheet was designed on the basis of the relationship between salt intake estimated using a brief self-administered diet history questionnaire (BDHQ) [32, 33] and 24-h urinary salt excretion in hypertensive outpatients [34]. The relationship between the salt check sheet score and the 24-h urinary salt excretion was validated in the 140 local residents, of whom 51 (36.4%) had hypertension [35]. As shown in Fig. 2, the total salt check sheet scores were significantly correlated with the 24-h urinary salt excretion levels (r = 0.27, p < 0.01). Thus, the combination of the specific guidance of salt reduction using salt check sheets and the assessment of urinary salt excretion seems effective in clinical practice. The authors investigated the effectiveness of repeated assessment of 24-h urinary salt excretion with the guidance of salt reduction provided by either doctors or dieticians in 103 hypertensive outpatients. The 24-h urine collections were performed 11.4 times on average during the mean observation period of 8.6 years [36]. As a result, urinary salt excretion significantly decreased from 9.6 g/day to 8.2 g/day (Fig. 3), indicating that repeated guidance of salt reduction combined with the assessment of urinary salt excretion led to a gradual decrease in salt intake. Nevertheless, it is difficult to achieve the target level of salt intake (<6 g/day); thus, other approaches, including the utilization of low-salt food, are necessary to achieve further reduction of salt intake.

Correlation between 24-h urinary salt excretion and salt check sheet scores. The dashed line indicates the identity line, and the solid line indicates the regression line. The circle is a normal-density ellipse (P = 0.95) enclosing the two variables [35]

Trends in the 24-h urinary salt excretion in 103 hypertensive patients who underwent 24-h urine collection 11.4 times on average during the mean observation period of 8.6 years [36]

Activities of the Japanese Society of Hypertension Salt Reduction Committee

Although salt intake by Japanese tends to decrease gradually, it remains high (10.8 g/day in men and 9.1 g/day in women, according to the National Health and Nutrition Survey in 2017) [19]. In Japan, a large proportion of salt is consumed through processed foods, and to promote nationwide salt reduction, it is necessary to launch educational campaigns to clarify the nutrient compositions labeled on food products as well as to promote the development and marketing of low-salt food. Presently, in Japan, the Na, but not the salt content, is required to be included in the nutritional information on processed foods; the salt content must be calculated by multiplying the Na content by 2.54. However, it has become mandatory to label processed foods with salt content by 2020. This regulation is expected to make it easier for consumers to understand the salt content of foods. Furthermore, the Japanese Society of Hypertension Salt Reduction Committee began to introduce low-salt foods judged to be comparable in taste to ordinary food products on its website while maintaining the recommend levels of labeled ingredients for the purposes of assisting salt reduction efforts [37]. If flavorful low-salt foods become available easily in the marketplace, their utilization may be advised not only for hypertensive patients but also for normotensive individuals to prevent hypertension.

Conclusion

Excessive salt intake is closely related to the prevalence and progression of hypertension. It also promotes the incidence of cardiovascular events. Salt reduction is particularly important in Japan because salt intake by Japanese individuals remains high. However, it is not easy to achieve the target salt intake level of <6 g/day advocated by the JSH2019. The assessment of salt intake by individuals is strongly recommended to provide effective guidance for salt reduction. Although there are several methods for the assessment of salt intake, reliable methods are difficult to perform, and simple methods are less reliable. In general medical facilities, the combination of questionnaires on the frequency of food intake and the estimation of 24-h urinary salt excretion by measuring Na in spot urine is practical and is recommended. The utilization of low-salt foods is also useful to reduce salt intake in hypertensive patients as well as in normotensive subjects. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Salt Reduction Committee continues to make efforts to reduce salt intake in the Japanese general population.

References

The Writing Committee of the Japanese Society of Hypertension (eds). Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension 2019 (JSH2019). Tokyo: Life Science Publishing Co., Ltd.; 2019, p. 64–75.

INTERSALT Cooperative Research Group. Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24 h urinary sodium and potassium excretion. Br Med J. 1988;297:319–28.

Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Engell RE.Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group et al. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:624–34.

He FJ, Macgregor GA. A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:363–84.

Graudal N, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G, McCarron DA. The significance of duration and amount of sodium reduction intervention in normotensive and hypertensive individuals: a meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:169–77.

He FJ, Li J, MacGregor GA. Effect of longer-term modest salt reductions on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;30:CD004937.

Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP, Meerpohl JJ. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2013;346:f1326.

Lennon SL, DellaValle DM, Rodder SG, Prest M, Sinley RC, Hoy MK, et al. 2015 Evidence analysis library evidence-based nutrition practice guideline for the management of hypertension in adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:1445–58.

Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Lear S, McQueen M.PURE, EPIDREAM and ONTARGET/TRANSCEND Investigators et al. Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from four studies. Lancet. 2010;388:465–75.

Cook NR, Appel LJ, Whelton PK. Sodium intake and all-cause mortality over 20 years in the trials of hypertension prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1609–17.

O’Donnell MJ, Mente A, Smyth A, Yusuf S. Salt intake and cardiovascular disease: why are the data inconsistent? Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1034–40.

He FJ, Campbell NRC, Ma Y, MacGregor GA, Cogswell ME, Cook NR. Errors in estimating usual sodium intake by the Kawasaki formula alter its relationship with mortality: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:1784–95.

Liu H, Gao X, Zhou L, Wu Y, Li Y, Mai J, et al. Urinary sodium excretion and risk of cardiovascular disease in the Chinese population: a prospective study. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:849–55.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guidelines for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M.ESC Scientific Document Group et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–104.

WHO. Guideline: sodium intake for adults and children. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2012.

Poorolajal J, Zeraati F, Soltanian AR, Sheikh V, Hooshmand E, Maleki A, et al. Oral potassium supplementation for management of essential hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0174967.

Vinceti M, Filippini T, Crippa A, de Sesmaisons A, Wise LA, Orsini N. Meta-analysis of potassium intake and the risk of stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004210.

The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. The results of the 2017 National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10904750/000351576.pdf.

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Dietary reference intakes for Japanese (2015). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/eiyou/syokuji_kij.

Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, et al. DASH Collaborative Research Group. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1117–24.

Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D.DASH Sodium Collaborative Research Group et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10.

Ndanuko RN, Tapsell LC, Charlton KE, Neale EP, Batterham MJ. Dietary patterns and blood pressure in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:76–89.

Ohta Y, Tsuchihashi T, Ueno M, Kajioka T, Onaka U, Tominaga M, et al. Relationship between the awareness of salt restriction and the actual salt intake in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:243–6.

Tsuchihashi T, Kai H, Kusaka M, Kawamura M, Matsuura H, Miura K. et al. Report of the Salt Reduction Committee of the Japanese Society of Hypertension (3) Assessment and application of salt intake in the management of hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2012;2012:p39–50. The Salt Reduction Committee of the Japanese Society of Hypertension.

Yamasue K, Tochikubo O, Kono E, Maeda H. Self-monitoring of home blood pressure with estimation of daily salt intake using a new electrical device. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:593–8.

Ohta Y, Tsuchihashi T, Miyata E, Onaka U. Usefulness of self-monitoring of urinary salt excretion in hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2009;31:690–7.

Takada T, Imamoto M, Sasaki S, Azuma T, Miyashita J, Hayashi M, et al. Effects of self-monitoring of daily salt intake estimated by a simple electrical device for salt reduction: a cluster randomized trial. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:524–30.

Kawasaki T, Itoh K, Uezono K, Sasaki H. A simple method for estimating 24 h urinary sodium and potassium excretion from second morning voiding urine specimen in adults. Clin Exp Pharm Physiol. 1993;20:7–14.

Tanaka T, Okamura T, Miura K, Kadowaki T, Ueshima H, Nakagawa H, et al. A simple method to estimate populational 24-h urinary sodium and potassium excretion using a casual urine specimen. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:97–103.

Takimoto H, Saito A, Htun NC, Abe K. Food items contributing to high dietary salt intake among Japanese adults in the 2012 National Health and Nutrition Survey. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:209–12.

Kobayashi S, Murakami K, Sasaki S, Okubo H, Hirota N, Notsu A, et al. Comparison of relative validity of food group intakes estimated by comprehensive and brief-type self-administered diet history questionnaires against 16 d dietary records in Japanese adults. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:1200–11.

Kobayashi S, Honda S, Murakami K, Sasaki S, Okubo H, Hirota N, et al. Both comprehensive and brief self-administered diet history questionnaires satisfactorily rank nutrient intakes in Japanese adults. J Epidemiol. 2012;22:151–9.

Sakata S, Tsuchihashi T, Ohta Y, Tominaga M, Arakawa K, Sakaki M, et al. Relationship between salt intake as estimated by a brief self-administered diet-history questionnaire (BDHQ) and 24-h urinary salt excretion in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:560–3.

Yasutake K, Miyoshi E, Kajiyama T, Umeki Y, Misumi Y, Horita N, et al. Comparison of a salt check sheet with 24-h urinary salt excretion measurement in local residents. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:879–85.

Ohta Y, Tsuchihashi T, Onaka U, Miyata E. Long-term compliance of salt restriction and blood pressure control status in hypertensive outpatients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;32:234–8.

The Japanese Society of Hypertension. Starting a low sodium diet—information from the Salt Reduction Committee to general public. http://jpnsh.jp/general_salt.html.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsuchihashi, T. Practical and personal education of dietary therapy in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res 43, 6–12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0340-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0340-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding hypertension diet among patients with hypertension

Scientific Reports (2025)