Abstract

In Japan, there were an estimated 43 million patients with hypertension in 2010. The management of this condition is given the highest priority in disease control, and the importance of lifestyle changes for the prevention and treatment of hypertension has been recognized in Japan. In particular, emphasis has been placed on increasing the levels of activities of daily living and physical exercise (sports). In this literature review, we examined appropriate exercise prescriptions (e.g., type, intensity, duration per session, and frequency) for the prevention and treatment of hypertension as described in Japanese and foreign articles. This review recommends safe and effective whole-body aerobic exercise at moderate intensity (i.e., 50–65% of maximum oxygen intake, 30–60 min per session, 3–4 times a week) that primarily focuses on the major muscle groups for the prevention and treatment of hypertension. Resistance exercise should be performed at low-intensity without breath-holding and should be used as supplementary exercise, but resistance exercise is contraindicated in patients with hypertension who have chest symptoms such as chest pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, the largest domestic and international problem with regard to internal diseases or syndromes is metabolic syndrome. Among the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome, the primary criterion is visceral fat obesity, while one of the other three criteria is hypertension. In Japan, the estimated number of patients with hypertension was 43 million (23 million men and 20 million women) in 2010 [1, 2]. The management of hypertension is given the highest priority in disease control.

Factors considered to be the cause of hypertension

Several factors, such as neurogenic, endocrine, vascular, endothelial, and renal mechanisms, are involved in the mechanisms of blood pressure (BP) control. Exercise has been reported to have a significant antihypertensive effect comparable to that of pharmacologic and nutritional interventions [3]. In brief, genetic factors (e.g., abnormal effects of various hormones [renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system, insulin, kinin–kallikrein system, catecholamines, prostaglandin system, etc.] involved in BP control and receptor abnormality) and lifestyle-related factors (e.g., high-salt intake, overeating, heavy drinking, stress overload, obesity [especially visceral fat obesity], and lack of exercise,) have been considered causes of hypertension. Lifestyle-related factors are particularly considered when implementing interventions, one of which is promoting exercise in individuals with a sedentary lifestyle.

In September 2018, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare reported the outline of the national health and nutrition survey conducted in November 2017 [4]. The report included 2017 data on individuals aged ≥ 20 years compared to the data collected 10 years earlier in terms of lifestyle habits:

-

(1)

Salt intake decreased in both men (10.8 g/day) and women (9.1 g/day);

-

(2)

Smoking decreased in both men (29.4%) and women (7.2%);

-

(3)

The prevalence of alcohol consumption increasing the risk of lifestyle-related diseases (volumes of pure alcohol ≥40 g/day among men and ≥20 g/day among women) did not change in men (14.7%) but increased in women (8.6%);

-

(4)

The prevalence of overweight and obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2) did not change in either men (30.7%) or women (21.9%);

-

(5)

The prevalence of strongly suspected diabetes mellitus did not change in either men (18.1%) or women (10.5%);

-

(6)

The proportion of individuals who engaged in regular exercise (30 min/day, twice a week), did not change in either men (35.9%) or women (28.6%), although the rate was particularly low in men and women in their 30 s (14.7%, 11.6%);

-

(7)

The daily average number of steps exhibited a declining trend in both men (6846 steps) and women (5867 steps);

-

(8)

The prevalence of sleep deprivation (i.e., less than 6 h of sleep) increased both in men (36.1%) and women (42.1%); and

-

(9)

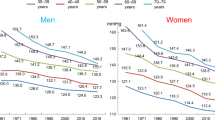

There was no significant change in the prevalence of systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg in either men (37.0%) or women (27.8%), but a declining trend was observed after adjusting for age.

According to these results, the causes of the still-high prevalence of patients with hypertension regardless of the reduction in salt intake and decrease in the number of smokers may be the low frequency of exercise and short durations of sleep/rest.

Classification of blood pressure and a hypertension management program

According to the Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019) [1], office BP in Japanese adults is classified as follows: Normotension is defined as a systolic BP < 120 mmHg and diastolic BP < 80 mmHg. High-normal BP is defined as systolic BP 120–129 mmHg and diastolic BP < 80 mmHg. Elevated BP is defined as systolic BP 130–139 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 80–89 mmHg. Hypertension is defined as systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg. Furthermore, stage 1 hypertension is defined as systolic BP 140–159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 90–99 mmHg, stage 2 hypertension as systolic BP 160–179 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 100–109 mmHg, and stage 3 hypertension as systolic BP ≥ 180 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 100 mmHg.

Prognostic factors used for risk stratification in hypertension management programs are old age (≥65 years), smoking, dyslipidemia, overweight, and obesity (BMI ≥ 25, especially visceral fat obesity), family history of early onset (<50 years of age) cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and organ failure/cerebrocardiovascular disease (brain, heart, kidney, blood vessels, and the fundus of the eye). The Japanese Society of Hypertension stratified cerebrocardiovascular risks using the above factors and office BP (Table 1) [1]. It is recommended to develop a hypertension management program at the first visit based on the risk stratification (Fig. 1).

Role of lifestyle, especially exercise, in the prevention and treatment of hypertension

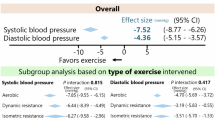

The JSH 2019 recommends lifestyle modification because it has an antihypertensive effect, enhances the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs when prescribed as needed, and facilitates weight loss (Table 2) [1]. According to the literature used for the development of the guidelines, salt reduction (average salt reduction = 4.6 g/day) [5], following the DASH diet [6], completing 30–60 min of aerobic exercise [7], and drinking moderately (the mean reduction in alcohol consumption = 76%) [8] reduce systolic BP by ~3–5 mmHg and diastolic BP by ~2–3 mmHg. Additionally, according to Leiter et al. [9], weight loss >4.5 kg has a comparable antihypertensive effect. Hackam et al. described the DASH diet and the recommended weekly intake of cereals, vegetables, fruit, low-fat or nonfat dairy products, lean meats, nuts, polyunsaturated fats and fish oils, and sweeteners [10].

Several studies have been conducted on the antihypertensive effect of exercise. Table 3 shows the mechanism of the antihypertensive effect proposed by the National Institutes of Health [11]. Exercise may reduce vascular resistance, arterial stiffness, sympathetic tone, psychological stress; improve vascular endothelial function and sodium regulation; and increase parasympathetic tone and arterial compliance, leading to lower BP. It is speculated that these factors work synergistically, thereby reducing systolic and diastolic BP.

Current status of exercise prescription for hypertension

There are many studies on the effect of exercise on the treatment and prevention of hypertension [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Table 4 shows the summary of the exercise recommended by Cleroux et al. [12]. According to their study, it is preferable to perform moderate-intensity exercise for ~1 h per session, 3–4 times a week, as an exercise intervention for the treatment and prevention of hypertension. Wang et al. [13] summarized the contents of exercise prescriptions recommended for patients with cardiovascular disease. Table 5 shows the recommended evidence-based aerobic exercise reported by Garber et al. in the report [14]. The exercise interventions that they recommended are considered equivalent to moderate-intensity exercise ≥5 days a week, requiring physical activity levels of ≥500–1000 metabolic equivalents (METs)∙min/week (or ≥8–17 METs∙h/week). Wang et al. summarized the moderate-intensity aerobic exercise recommended in the Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription of the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) (Table 6) as follows: 40–60% of either heart rate reserve or oxygen consumption reserve, 64–76% of maximum heart rate, 46–64% of maximum oxygen uptake, and an exercise intensity of ≥3–6 METs. The ACSM Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (7th ed.) lists the examples of exercise interventions to improve physical fitness (e.g., type of exercise and patients for whom the exercise interventions are recommended and examples of exercise interventions) (Table 7) [19]. Recommended exercise interventions that can be performed anywhere and are not too expensive include walking, cycling, jogging, rowing, swimming, and water aerobics. Based on the above results, Wang et al. [13] summarized the contents of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise recommended for the treatment and prevention of hypertension as shown in Table 8.

Exercise behavior in patients with hypertension

The ACSM’s Guidelines for Testing and Prescription 10th Edition [20] listed the following considerations and points for exercise prescription:

-

(1)

BP control levels, recent changes in antihypertensive treatment, side effects of drugs, presence of target organ disease, other complications, and age should be considered. Exercise prescriptions should be revised according to the above-described factors. In general, the prescriptions should be gradually modified. Based on the FITT principle (F: frequency, I: intensity, T: time, and T: type), a substantial increase in exercise intensity should be avoided, particularly in most patients with hypertension.

-

(2)

Relatively mild exercise and exercise at a heart rate <85% of age-predicted maximum heart rate is likely to cause a stronger BP response even if resting BP is controlled with antihypertensive drugs. In some cases, exercise tolerance testing may be effective for determining exercise heart rate corresponding to increased BP in such patients.

-

(3)

It is prudent to maintain systolic BP ≤ 220 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≤ 105 mmHg during exercise.

-

(4)

While high-intensity aerobic exercise (i.e., ≥60% of oxygen uptake reserve) is not necessarily a contraindication for patients with hypertension, moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (40–59% of oxygen uptake reserve) is generally recommended for patients with hypertension to improve the relative risk ratio.

-

(5)

Patients with hypertension are often overweight or obese. To promote weight loss, exercise prescriptions should focus on reducing calorie intake and increasing calorie expenditure.

-

(6)

Holding breath during weightlifting (i.e., Valsalva maneuver) can cause very high-BP response, vertigo, and syncope.

-

(7)

Exercise tolerance testing and high-intensity exercise training should be performed under medical surveillance in patients with hypertension at moderate or high risk for cardiac complications until the safety of the prescribed exercise is confirmed.

-

(8)

Beta-blockers, particularly the nonselective type, may primarily reduce submaximum and maximum exercise capacity in patients without myocardial ischemia. The peak exercise heart rate achieved during a standard exercise tolerance test should be used to determine exercise intensity. If the peak exercise heart rate is unavailable, perceived exertion should be used instead.

-

(9)

Antihypertensive drug treatment, e.g., alpha blockers, calcium antagonists, and vasodilators, may lead to a sudden decrease in BP after exercise. Therefore, the exercise should be stopped gradually, and sufficient time for cooling down should be allowed until the BP and heart rate return to the resting level while they are closely monitored.

-

(10)

Aerobic exercise has a rapid antihypertensive effect, inducing physiological responses related to postexercise hypotension. Postexercise hypotension in patients should be closely monitored. Patients should be informed about the methods of postexercise BP control, e.g., regular light-intensity exercise such as slow walking.

-

(11)

If patients with hypertension have an ischemic episode during exercise, refer to the guidelines for exercise prescription for patients with ischemic heart disease.

According to the JSH 2019 guideline [1], exercise therapy is recommended for patients with abnormal BP (stage 1 and stage 2 hypertension, high BP and normal-high BP).

Conclusion

Exercise prescriptions for the treatment and prevention of hypertension should be developed considering the abovementioned points. Regular moderate-intensity exercise (3–4 days a week) is essential for effective and safe exercise programs. Furthermore, such exercises in combination with supplementary resistance exercise may be appropriate for patients with hypertension and those who exercise for the prevention of hypertension, given that they have no chest symptoms such as chest pain or history of cardiac or pulmonary disease.

References

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Miura K, Nagai M, Ohkubo T. Epidemiology of hypertension in Japan. Circ J. 2013;77:2226–31.

Moraes-Silva IC, Mostarda CT, Silva-Filho AC, Irigoyen MC. Hypertension and exercise training: evidence from clinical studies. In: Xiao J, editors. Exercise for cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment, advances in experimental medicine and biology 1000. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2017. p. 65–84.

Nutrition survey section, Health department of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. The results of national health and nutrition survey 2017. Tokyo, The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; 2018; 1–33. (Japanese)

He FJ, MacGregor GA. Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Implication for public health. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:761–70.

Socks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10.

Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Cook JV, et al. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2006;24:215–33.

Nakamura K, Okamura T, Hayakawa T, Hozawa A, Kadowaki T, Murakami Y, et al. The proportion of individuals with alcohol-induced hypertension among total hypertensives in a general Japanese population: NIPPON DATA90. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:663–8.

Leiter LA, Abbott D, Campbell NRC, Mendelson R, Ogilvie RI, Chockalingam A. Recommendations on obesity and weight loss. CMAJ. 1999;160(9 Suppl):S7–12.

Hackam DG, Khan NA, Hemmelgarn BR, Rabkin SW, Touyz RM, Campbell NR, et al. The 2010 Canadian hypertension education program recommendations for the management of hypertension. Part 2-therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:249–58.

Diaz KM, Shimbo D. Physical activity and the prevention of hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2013;15:659–68.

Cleroux J, Feldman RD, Petrella RJ. Recommendations on physical exercise training. CMAJ. 1999;160(9 Suppl):S21–2.

Wang L, Ai D, Zhang N. Exercise dosing and prescription-playing it safe: dangers and prescription. In: Xiao J, editor. Exercise for cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment, advances in experimental medicine and biology 1000. Singapore, Springer Nature; 2017; 357–87.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1334–59.

Sharman JE, La Gerche A, Coombes JS. Exercise and cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:147–58.

Izdebska E, Cybulska I, Izdebski J, Makowiecka-Ciesla M, Trzebski A. Effects of moderate physical training on blood pressure variability and hemodynamic pattern in mildly hypertensive subjects. J Physiol Pharm. 2004;55:713–24.

Hansen D, Niebauer J, Cornelissen V, Barna O, Neunhaeuserer D, Stettler C, et al. Exercise prescription in patients with different combinations of cardiovascular disease risk factors: a consensus statement from the EXPERT working group. Sports Med. 2018;48:1781–97.

Hackam DG, Khan NA, Hemmelgarn BR, Rabkin SW, Touyz RM, Campbell NR, et al. The 2010 Canadian hypertension education program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part 2–therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:249–58.

Armstrong LE, Brubaker PH, Whaley MH, Otto RM. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (7th ed.), In: Whaley MH, Senior editor. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005, p. 366.

Colberg-Ochs SR, Ehrman JK, Johann J, Kokkinos P, Pack PQ, Lignor G. Chapter 10: Exercise prescription for individuals with metabolic disease and cardiovascular disease risk factors. In: Riebe D, senior editor. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (10th ed.), Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2018; 279–83.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sakamoto, S. Prescription of exercise training for hypertensives. Hypertens Res 43, 155–161 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0344-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0344-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparison of the relationship between key demographic features and physical activity levels across 22 countries

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

A higher resting heart rate is associated with cardiovascular event risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus without known cardiovascular disease

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Comment on “Prescription of exercise training for hypertensives”

Hypertension Research (2021)

-

Recreational beach tennis reduces 24-h blood pressure in adults with hypertension: a randomized crossover trial

European Journal of Applied Physiology (2021)