Abstract

Individual shear rate therapy (ISRT) evolved from external counterpulsation with individual treatment pressures based on Doppler ultrasound measurements. In this study, we assessed the effect of ISRT on blood pressure (BP) in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Eighty-four patients with symptomatic CAD were included in the study. Forty-one patients were enrolled for 6 weeks, comprising 30 sessions of ISRT; 43 age- and sex-matched patients represented the control group. The 24-h BP was determined by measuring the pulse transit time before and after 6 weeks of ISRT or the time-matched control. Participants were divided into three groups according to the 24-h BP before treatment: BP1 < 130/80 mmHg (normotensive); BP2 ≥ 130–140/80 mmHg (moderate hypertensive); BP3 > 140/80 mmHg (hypertensive). After 30 sessions of ISRT, the 24-h BP decreased significantly, whereas no changes were observed in the controls. The BP-lowering effect correlated with the 24-h BP before therapy (systolic: r = −0.78; p < 0.001; diastolic: r = −0.76; p < 0.001). In BP1, the systolic BP decreased by 4.3 ± 6.4 mmHg (p = 0.011), and the diastolic BP decreased by 4.8 ± 11.0 mmHg (p = 0.032); in BP2, the systolic BP decreased by 13.3 ± 7.5 mmHg (p < 0.001), and the diastolic BP decreased by 5.0 ± 7.5 mmHg (p = 0.002); and in BP3, the systolic BP decreased by 22.9 ± 11.4 mmHg (p < 0.001), and the diastolic BP decreased by 9.1 ± 9.5 mmHg (p = 0.003). Our findings demonstrate that ISRT reduces BP in patients with CAD. The higher the initial BP the greater the lowering effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 20–30% of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) fail to respond to revascularization procedures and still suffer from angina pectoris and dyspnea despite optimal medical therapy [1, 2]. Enhanced external counterpulsation (ECP/EECP) is recommended as a noninvasive therapeutic option for these patients [3]. EECP uses three sets of cuffs wrapped around the lower extremities, inflating in diastole, and deflating at the onset of systole. The cuff inflation improves the diastolic blood flow significantly and leads to a profound increase in the intra-arterial shear rate and fluid shear stress (FSS) [4]. In ECP, the applied treatment pressure is usually high (up to 250 or 300 mmHg); this is based on the hypothesis that increasing the coronary blood pressure (BP) induces collateralization of the coronaries [5,6,7,8]. The high treatment pressure during EECP leads to side effects and in parallel decreases the acceptance of therapy [9]. Therefore, an alternative treatment strategy is necessary. A novel method is the recently described individual shear rate therapy (ISRT) [4]. It is based on the individual detection of shear rates in each patient and thereby the basis for the calculation of optimal cuff pressures [9]. As a result, it is possible to determine the most beneficial treatment pressure ranging between 160 and 220 mmHg for each patient individually, so that high, nonindividual cuff pressures are no longer necessary [4]. Recently, we showed that ISRT with low individual treatment pressures is an effective therapy in patients with symptomatic CAD to improve cardiac fitness and arterial stiffness and to reduce episodes of angina pectoris and dyspnea [10].

ISRT therefore represents a novel approach in precision medicine in the field of counterpulsation. The aim of the current study was to investigate whether ISRT is an effective treatment in patients with symptomatic CAD to reduce BP and whether the BP-lowering effect is dependent on the average BP level before treatment.

In previous reports, there are different findings about the effect of ECP on BP. Some articles have reported a decrease in BP after treatment with EECP [11,12,13], whereas other investigators could not find a BP-lowering effect [14]. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies on the BP-lowering effect in different BP groups based on the systolic 24-h mean value before therapy.

Methods

Study population

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Association of North Rhine (Germany). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after verbal and written information was given. Eighty-four patients with symptomatic CAD were included in the study. A total of 41 patients were enrolled for 30 sessions of ISRT; 43 age- and sex-matched CAD patients who did not want to participate in the ISRT program represented the time-matched control group. All patients failed to respond to revascularization procedures by either percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting. Included were patients suffering from angina pectoris (CCS I-III) and/or dyspnea (NYHA I-III). The last coronary angiography examination for each patient was performed in the 12 months before starting ISRT. All patients in the ISRT and control groups received an optimal pharmacologic therapy, which did not change during the study period. Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery bypass graft within the past 4 weeks, atrial fibrillation > 90 bpm, severe aortic valve insufficiency, uncontrolled hypertension > 180/100 mmHg, severe symptomatic peripheral vascular disease III/IV, active thrombophlebitis in lower limbs, pulmonary hypertension, or pregnancy.

ISRT

ISRT is a noninvasive procedure that is an adaption of ECP. We used a commercial ECP system (Pu Shi Kang, Electronics, Zhejiang, China). The patients remained in the supine position during the therapy. Three pairs of pneumatic cuffs were wrapped around the calves, thighs, and hips. The inflation and deflation of the pneumatic cuffs were triggered by an electrocardiogram. Upon diastole, the cuffs were inflated, and at the onset of systole, they were deflated again. To determine the treatment pressure, we assessed the individual blood flow parameters for each patient in the common carotid artery with a high-definition ultrasound system (Philips, HD 11, Germany) on days 2, 12, and 22 of treatment. Signals were registered for six heart cycles, and the maximum systolic blood flow velocity, acceleration, and relative peak slope index were calculated as previously described [4]. Doppler flow parameters were analyzed at different treatment pressures starting from 0 mmHg and continuing to 80, 120, 160, 200, and 220 mmHg. Each treatment pressure was maintained for 4 min; Doppler flow parameters were assessed at the 3rd minute mark. The individually calculated treatment pressure varied from 160 to 220 mmHg. Each patient in the therapy group underwent ISRT for 30 sessions (6 weeks, five times per week) for 55 min.

Twenty-four hour blood pressure (24-h BP)

The 24-h BP was determined by measuring the pulse transit time (PTT) using the SOMNOtouchTM NIBP device (SOMNOmedics, Randersacker, Germany). SOMNOtouchTM NIBP is a cuffless continuous BP monitor that can derive BP levels from PTT measurements on the basis of a stretch–strain relationship model over 24 h. It has been shown that the SOMNOtouchTM NIBP BP monitor has passed the requirements of the ESH international protocol, revision 2010 [15].

The PTT is defined as the time that a pulse wave needs to travel from the left ventricle to a certain site of the arterial system. The SOMNOtouchTM NIBP monitor uses the period between the R-wave of the ECG and the appearance of the pulse wave on finger plethysmography, which were recorded simultaneously.

DOMINO software (DOMINO light 1.5.0, SOMNOmedics, Randersacker, Germany) calculates the BP based on a PTT-BP relation. The PTT depends on the wall stress of the blood vessels and correlates with the BP. The BP measurement is continuous because data pairs for systolic and diastolic BP are obtained for each heartbeat [16]. To calculate the BP with the PTT, it is necessary to conduct a one-point calibration with a standard BP measurement, as described by Riva Rocci and Korotkoff [17]. The calibration was performed immediately before starting the data collection in each patient under resting conditions. To recheck the BP values of SOMNOtouchTM NIBP, we measured the BP again with standard calibrated sphygmomanometers at the end of the 24-h evaluation period of each patient. This allowed a comparison of SOMNOtouchTM NIBP and cuff BPs at that time point. To validate the PTT method, we added a second calibration to all recordings. An interpolation of the BP values between those two calibration points was performed.

The 24-h BP measurements were divided into daytime and nighttime values according to individual waking and bedtimes. We obtained the daytime BP (systolic and diastolic), the nighttime BP (systolic and diastolic), the 24-h BP (systolic and diastolic), the mean daytime, nighttime and 24-h arterial pressure (MAP), and the daytime, nighttime and 24-h heart rate (HR).

All measurements were conducted at baseline and 6 weeks following ISRT or the time-matched control. Data were analyzed by classifying the participants according to the baseline 24-h BP before treatment into the following subgroups: BP1 < 130/80 mmHg (normotensive); BP2 ≥ 130–140/80 mmHg (moderate hypertensive); and BP3 > 140/80 mmHg (hypertensive).

Blood pressure

The systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were obtained before and at the end of each individual ISRT session with standard calibrated sphygmomanometers.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, the SPSS software package (SPSS 22.0) was used. Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and noncontinuous data are presented as percentages. All data were tested for distribution normality with the Shapiro–Wilk test.

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to test differences between the intervention group and the control group at study entry. Statistical significance was designated at p ≤ 0.05. Comparisons of data collected before and after 30 sessions of ISRT (or after 6 weeks without ISRT in controls) were evaluated with a paired t test. Statistical relationships between two continuous variables were analyzed with the Pearson correlation test. Differences between BP groups before and after 30 sessions of ISRT were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis.

Results

Clinical data

Eighty-four patients with symptomatic CAD (61 men, 23 women; 38–83 years) were included in the study. A total of 41 patients were enrolled for 30 sessions of ISRT (treatment group); 43 age- and sex-matched CAD patients who did not want to participate in the ISRT program represented the time-matched control group. There were no differences between the two study groups at study entry with respect to cardiovascular risk factors, CAD presentation, further disease, BP, and antihypertensive drug use. Table 1 contains the clinical baseline characteristics and the BP measurements and antihypertensive drugs in use at study entry. Medications were not changed during the treatment period. During the study period, we did not observe any adverse clinical events. In the ISRT group, we observed some minor side effects, such as leg and back pain in 4 patients and paresthesia in 8 of the 41 patients.

Twenty-four hour BP

At study entry, the daytime, nighttime, 24-h BP, and MAP did not differ between the treatment and control groups (Table 1). After 30 sessions of ISRT (6 weeks), we found a significant decrease in the systolic and diastolic BP; 75.9% of patients treated with ISRT but only 34.9% of the patients undergoing solely antihypertensive treatment (p < 0.001) showed a significant decrease in the 24-h BP. In some cases, the BP increased in the control group but not in the ISRT group (39.5% vs. 0%; p < 0.001). On average, the 24-h BP decreased in the ISRT group by 13 mmHg for the systolic BP (p < 0.001) and 7 mmHg for the diastolic BP (p < 0.001). We divided the BP into daytime and nighttime values according to individual waking and bedtimes. In the daytime, the systolic and diastolic BP decreased by 14 mmHg (p < 0.001) and 8 mmHg (p < 0.001), respectively; in the nighttime, the systolic and diastolic BP decreased by 11 mmHg (p < 0.001) and 7 mmHg (p < 0.001), respectively. We also demonstrated a significant decrease in the 24-h MAP after 6 weeks of ISRT (96 ± 11 to 86 ± 9 mmHg, p < 0.001). In the control group, the daytime, nighttime and 24-h BP and the 24-h MAP did not change after 6 weeks compared with baseline.

The BP-lowering effect in the treatment group correlated with the 24-h systolic mean value before therapy (systolic: r = 0.78; p < 0.001; diastolic: r = 0.76; p < 0.001), but this was not observed in the control group (Fig. 1). There were no correlations between the BP-lowering effect and age, BMI, sex, or antihypertensive medications.

Correlation of the systolic blood pressure-lowering effect with the 24-h mean value before therapy. In the treatment group, there was a significant correlation for the blood pressure-lowering effect after 6 weeks (b) but not after each individual treatment session (c). ISRT individual shear rate therapy, SBP systolic blood pressure

Participants were divided into three groups according to the 24-h BP at baseline before treatment: BP1 < 130/80 mmHg (normotensive) (ISRT, n = 14; controls, n = 17); BP2 ≥ 130–140/80 mmHg (moderate hypertensive) (ISRT, n = 15; controls, n = 13); and BP3 > 140/80 mmHg (hypertensive) (ISRT, n = 12; controls, n = 13). After 30 sessions of ISRT (6 weeks), we demonstrated in all BP groups a significant decrease in the systolic and diastolic daytime-, nighttime-, and 24-h BP; the MAP only decreased in BP3 (>140/80 mmHg) (Table 2). In all control groups, the daytime, nighttime and 24-h BP and the 24-h MAP did not change after 6 weeks compared with the baseline values (Table 2).

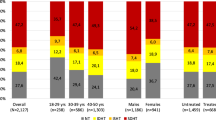

In patients treated with ISRT, the prevalence of a decreased systolic 24-h BP was different among the BP groups, with 43% of patients in BP1, 86.7% in BP2, and 100% in BP3 (p < 0.001) showing a BP-lowering effect of at least 5 mmHg. In the controls, there were no differences in the BP-lowering effect among the groups (Fig. 2).

Frequency of consistent, decreasing, and increasing 24-h BP values in different blood pressure groups. In patients treated with ISRT, the prevalence of a decrease in the systolic 24-h BP was different among the blood pressure groups, with 42.9% of patients in BP1, 86.7% in BP2, and 100% in BP3 (p < 0.001) showing a blood pressure-lowering effect of at least 5 mmHg (a). In controls, there were no differences in the blood pressure-lowering effect among the groups (b). BP blood pressure, ISRT individual shear rate therapy

The systolic 24-h BP decreased after 30 sessions of ISRT in BP1 by 4.3 ± 6.4 mmHg (p = 0.011), in BP2 by 13.3 ± 7.5 mmHg (p < 0.001), and in BP3 by 22.9 ± 11.4 mmHg (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3a). The one-way ANOVA results showed significant differences in the extent of the systolic BP-lowering effect among the groups (p < 0.001). The Tukey post hoc analysis demonstrated significant differences between BP1 and BP2 (p = 0.024), BP1 and BP3 (p < 0.001), and BP2 and BP3 (p = 0.017). In the treatment group, we also observed a DBP-lowering effect in all groups: the DBP decreased in BP1 by 4.8 ± 11.0 mmHg (p = 0.032), in BP2 by 5.0 ± 7.5 mmHg (p = 0.002), and in BP3 by 9.1 ± 9.5 mmHg (p = 0.003) (Fig. 3c). Among the three BP groups, there were no significant differences in the extent of the diastolic BP decrease. In the controls, there were no changes after 6 weeks in the SBP or DBP in any BP group (Fig. 3b, d).

The 24-h BP at study entry and after 6 weeks in different blood pressure groups. Participants were divided into three groups according to the 24-h BP at baseline before treatment: BP1 < 130/80 mmHg (normotensive), BP2 ≥ 130–140/80 mmHg (moderate hypertensive), and BP3 > 140/80 mmHg (hypertensive). After 6 weeks in the treatment group, there was a significant decrease in the systolic (a) and diastolic (c) 24-h BP in all BP groups but not in the controls (b, d). BP blood pressure, ISRT individual shear rate therapy

Clinical blood pressure

The SBP and DBP were obtained daily before and at the end of each individual ISRT session with standard calibrated sphygmomanometers. Overall, there was a mean decrease of 9.5 ± 5.6 mmHg in the SBP (p < 0.001) and of 3.0 ± 2.9 mmHg in the DBP (p < 0.001) after individual treatment sessions. In contrast to the 24-h BP measurements after 6 weeks of ISRT, the single BP measurements obtained after each individual ISRT session showed no correlation with the 24-h baseline BP (r = 0.113; p = 0.483) (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, no differences in the decrease after each individual treatment session could be determined among the BP groups.

To determine the time course of the decrease in BP, we analyzed the BP data at study entry (before ISRT) and after 2, 4, and 6 weeks of ISRT. In each case, we analyzed the mean value of 3 consecutive days. We observed a strong decrease in the systolic and diastolic BP after 2 weeks of ISRT and another decrease in BP after 4 weeks of ISRT (Fig. 4a, b; upper graph).

Time course of decrease in BP after ISRT. BP was determined at study entry (before ISRT) and after 2, 4, and 6 weeks of ISRT with standard calibrated sphygmomanometers. In each case, we analyzed the mean value of 3 consecutive days. The systolic and diastolic BP decreased after just 2 weeks of ISRT and after 4 weeks of ISRT (a and b, respectively, upper graph). The BP data measured immediately before and at the end of each individual ISRT session showed that the BP also decreased directly after an individual treatment session and that this decrease was independent of the time course (a and b, lower graph). DBP diastolic blood pressure, ISRT individual shear rate therapy, SBP systolic blood pressure

In addition, we analyzed the BP data before and at the end of each individual ISRT session. The measurements at study entry and after 2, 4, and 6 weeks showed that this decrease was independent of the time course (Fig. 4a, b; lower graph).

Heart rate

Overall, the HR did not change in the ISRT or control group (ISRT group: 69 ± 8 vs. 66 ± 8 bpm, p = 0.134; control group: 66 ± 9 vs. 66 ± 10 bpm, p = 0.655). In the BP3 (hypertensive) ISRT group, we observed an HR-lowering effect (74 ± 9.6 vs. 69 ± 8.4 bpm; p = 0.003).

Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes

Overall, the patients in the ISRT group described a strong improvement in their complaints: 37/41 patients reported having fewer episodes of angina pectoris and dyspnea after 30 sessions of ISRT (CCS: 2.1 ± 0.8 to 1.29 ± 0.4, p < 0.001; NYHA: 2.0 ± 0.7 to 1.29 ± 0.5, p < 0.001). The CCS angina class and NYHA dyspnea class decreased significantly in BP1 (normotensive), BP2 (moderate hypertensive), and BP3 (hypertensive). There were no differences among the groups (CCS: p = 0.745; NYHA: p = 0.537). Overall, in the control group, there was no difference between baseline and after 6 weeks (CCS: 2.2 ± 0.7 to 2.1 ± 0.7, p = 0.161; NYHA: 1.9 ± 0.6 to 1.8 ± 0.5, p = 0.257). All analyzed values are listed in Table 2.

Discussion

ISRT is an adaptation of ECP based on the increase in the intra-arterial shear rate and FSS. Like ECP, ISRT uses a series of three cuff pairs placed on the calves, thighs, and hips, which are triggered by an electrocardiogram. Cuff inflation upon diastole improves the diastolic blood flow significantly and leads to a profound increase in the intra-arterial shear rate and FSS [9]. In ECP, the applied treatment pressure is usually high––up to 250 or 300 mmHg. [5, 7, 8, 18,19,20] In contrast to ECP, with ISRT, we used considerably lower treatment pressures ranging from 160 to 220 mmHg, which were individually assessed for each patient.

In our previous study, we showed that ISRT is an effective treatment option for patients with symptomatic CAD who fail to respond to revascularization procedures [10]. In the current study, we investigated whether ISRT is an effective treatment in patients with CAD to reduce the BP and whether the lowering effect depends on the average BP level before treatment. An optimal BP adjustment, especially for patients with CAD, is important to avoid cardiovascular events [21,22,23]. Sometimes it is difficult to reach the optimum BP target solely with antihypertensive agents [24,25,26], so it is of great importance to know whether ISRT can contribute to reducing BP. To assess the effect of ISRT on BP, the levels of antihypertensive medications were held constant during the study period.

Our findings demonstrate a significant decrease in the systolic and diastolic 24-h BP in the intervention group and no changes in BP in the control group. On average, ISRT reduced the SBP by 13 mmHg and the DBP by 7 mmHg. Moreover, we found that the BP-lowering effect depends on the systolic 24-h baseline BP at study entry (r = −0.78; p < 0.001).

We divided the patients and controls into three groups according to 24-h BP at baseline before treatment. We found that the pressure-lowering effect in the treatment group correlated with the 24-h systolic mean value before therapy. In patients with a higher baseline BP, the lowering effect was stronger: after 6 weeks of ISRT, the systolic 24-h BP decreased by 4.3 mmHg, 13.3 mmHg, and 22.9 mmHg in patients with normotensive BP (BP1 < 130/80 mmHg) (p = 0.011), moderate hypertensive BP (BP2 ≥ 130–140 mmHg) (p < 0.001), and hypertensive BP (BP3 > 140 mmHg) (p < 0.001), respectively.

The results of our research could explain the divergent findings regarding the BP-lowering effect in different EECP studies. For example, May et al. could not determine an effect of EECP on ambulatory BP [14], whereas Campbell et al. found a significant decrease in the SBP of 6 mmHg [11]. Another previous study demonstrated a decrease of 10 mmHg in the SBP after 35 sessions of EECP [12].

In these studies, the patients had different baseline BPs at study entry. The patients in the study by May et al. had very low baseline BPs, with a mean systolic BP of 114 mmHg, while the patients in the studies by Sardina and Bondesson had higher baseline BPs, with a mean of 130 mmHg [8, 12].

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to report a BP-lowering effect in different BP groups based on the systolic 24-h mean value before therapy. There has been only one other study in which data were analyzed by stratifying patients based on the baseline SBP into subgroups; however, in contrast to our study, in that study, the division of the subgroups was based on single BP measurements [11]. Nonetheless, consistent with our results, the authors reported a greater BP-lowering effect in patients with a baseline SBP > 140 mmHg (n = 7). In contrast to other studies [8, 11], we also observed a DBP-lowering effect both overall and in all subgroups. A possible explanation is that ISRT could be more effective than EECP. Common ECP lacks an evaluation for treating each patient individually, and the applied treatment pressure is very high. Buschmann et al. [4] have shown that a therapy pressure up to 220 mmHg leads to a deceleration, which could reduce the positive effect of counterpulsation. In our study, we determined the BP by measuring the PTT. The measurement is continuous because data pairs for the SBP and DBP were obtained for each heartbeat investigated [16]. It can be assumed that the PTT method is more reliable than methods based only on BP measurements collected every 30 min or clinical BP measurements. The conventional 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring device is discontinuous, as it measures the BP every 15–30 min. Therefore, it is possible that the maximum and minimum BP values and smaller fluctuations in BP are not detected. With respect to patients with OSA, fluctuations in BP due to desaturation or apnea/hypopnea can be missed. This could affect the mean BP value.

In our study, we observed a relatively high population of patients with sleep apnea syndrome in the ISRT group as well as in the control group (19 of 41 in the ISRT group and 19 of 43 in the control group, 38 of 84 patients overall). Twenty-one of these thirty-eight patients were previously diagnosed with OSA. They underwent CPAP therapy (17/21) for at least 1 year. During the study, all settings for CPAP therapy were not changed. For a subgroup of 17 out of these 38 patients, we assumed sleep apnea due to nightly desaturations measured by SOMNOtouchTM NIBP. All 17 patients were examined by polysomnography (using a SOMNOscreen plus system from SOMNOmedics GmbH, Randersacker, Germany). We could confirm the previously presumed diagnosis for all of them. These 17 patients underwent CPAP therapy after the termination of our study.

Our results demonstrate that overall, in BP1 (<130 mmHg) and BP2 (≥130–140 mmHg), the HR was unchanged. In patients with a baseline BP > 140 mmHg (BP3), we determined a reduction in the HR of 5 bpm (p = 0.030). Previous studies could not determine an effect of EECP on HR [8, 11, 13, 27, 28]. In all these examinations, the patients had a low systolic baseline BP < 132 mmHg. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that there is an HR-lowering effect in patients with higher BPs. Moreover, in contrast to other studies, we determined the average HR over 24 h. It is possible that our measurements are more precise. Another reason for the divergent findings in the different BP groups could be a varying proportion of patients with atrial fibrillation or a cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED). Three of the twelve patients (25%) in this group had a previous diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. One of these three patients had paroxysmal atrial fibrillation at study entry. One of the twelve patients (8.3%) had a CIED. The percentage of patients with atrial fibrillation and/or a CIED in the other BP groups was as follows: BP1: atrial fibrillation = 6/14 (42.9%), CIED = 4/14 (28.6%); BP2: atrial fibrillation = 2/15 (13.3%), CIED = 1/15 (6.7%). Nevertheless, if we exclude patients with atrial fibrillation and/or a CIED, we still observed a heart-lowering effect after 30 sessions of ISRT in only BP3.

We found that patients treated with ISRT had fewer episodes of angina pectoris and dyspnea. The improvement in BP may contribute to the clinical benefit of ISRT. However, the precise mechanisms underlying the benefits of ISRT are not completely understood [4]. Endothelial shear stress from increased diastolic augmentation after ISRT likely leads to an increase in NO and a downregulation of ET-1 (endothelin-1), and thus the recruitment of more collateral vessels [4]. Furthermore, the increased endothelial shear stress produces circulating angiogenic growth factors, which have vasodilatory properties [29]. The improvement in BP, as shown in our study, may represent a physiological response that reflects the improved endothelial function and vasoreactivity. As a result, clinical benefits, including a reduction in the CCS angina class, are possible. Further investigations are important to clarify this relationship.

Limitations

In the current study, we analyzed the effect of ISRT in 41 CAD patients compared with 43 controls. Although the patient number was small, we found significant results from the data. Due to the small number of patients, general conclusions are to be drawn with care. We measured the effects of ISRT after 6 weeks of treatment. However, a long-term comparison of the BP response in patients treated with ISRT versus only pharmacological treatment is required.

Conclusions

The present results indicate that ISRT is an effective treatment option for patients with symptomatic CAD to reduce the systolic and diastolic 24-h BP. There was a varying effect on the 24-h BP depending on the baseline 24-h BP before therapy: the higher the initial BP the greater the lowering effect. Improvements in BP may contribute to the clinical benefits of ISRT. We found that patients treated with ISRT had fewer episodes of angina pectoris and dyspnea.

References

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–57.

Henry TD, Satran D, Jolicoeur EM. Treatment of refractory angina in patients not suitable for revascularization. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:78–95.

Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the taskforce on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949–3003.

Buschmann EE, Brix M, Li L, Doreen J, Zietzer A, Li M, et al. Adaption of external counterpulsation based on individual shear rate therapy improves endothelial function and claudication distance in peripheral artery disease. Vasa. 2016;45:317–24.

Gurovich AN, Braith RW. Enhanced external counterpulsation creates acute blood flow patterns responsible for improved flow-mediated dilation in humans. Hypertension Res. 2013;36:297–305.

Sharma U, Ramsey H, Tak T. The role of enhanced external counter pulsation therapy in clinical practice. Clin Med Res. 2013;11:226–32.

Braith RW, Conti CR, Nichols WW, Choi CY, Khuddus MA, Beck DT, et al. Enhanced external counterpulsation improves peripheral artery flow mediated dilation in patients with chronic angina: a randomized sham-controlled study. Circulation. 2010;122:1612–20.

Sardina PD, Martin JS, Avery JC, Braith RW. Enhanced external counterpulsation improves biomarkers of glycemic control in patients with non-insulin-dependent type II diabetes mellitus for up to 3 months following treatment. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53:745–75.

Buschmann I, Pries A, Styp-Rekowska B, Hillmeister P, Loufrani L, Henrion D, et al. Pulsatile shear and Gja5 modulate arterial identity and remodeling events during flow-driven arteriogenesis. Development. 2010;137:2187–96.

Picard F, Panagiotidou P, Wolf-Pütz A, Buschmann I, Buschmann E, Steffen M, et al. Usefulness of individual shear rate therapy, new treatment option for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2018;121:416–22.

Campbell AR, Satran D, Zenovich AG, Campbell KM, Espel JC, Arndt TL, et al. Enhanced external blood counterpulsation improves systolic blood pressure in patients with refractory angina. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1217–22.

Bondesson S, Pettersson T, Ohlsson O, Hallberg IR, Wackenfors A, Edvinsson L. Effects on blood pressure in patients with refractory angina pectoris after enhanced external counterpulsation. Blood Press. 2010;19:287–94.

Casey DP, Beck DT, Nichols WW, Conti CR, Choi CY, Khuddus MA, et al. Effects of enhanced external counterpulsation arterial stiffness and myocardial oxygen demand in patients with chronic angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 2011;10:1466–72.

May O, Khair WA. Enhanced external counterpulsation has no lasting effect on ambulatory blood pressure. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:21–24.

Bilo G, Zorzi C, Ochoa Munera JE, Torlasco C, Giuli V, Parati G. Validation of the Somnotouch-NIBP noninvasive continuous blood pressure monitor according to the European Society of Hypertension International Protocol revision 2010. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20:291–4.

Bartsch S, Ostojic D, Schmalgemeier H, Bitter T, Westerheide N, Eckert S, et al. Validierung der kontinuierlichen nicht-invasiven Blutdruckmessung mittels Puls-Transit-Zeit. Dtsch medizinische Wochenschr. 2010;135:2406–12.

Eckert S. 100 Jahre Blutdruckmessung nach Riva-Rocci und Korotkoff: Rückblick und Ausblick. Austrian J Hypertension. 2006;10:7–13.

Bonetti PO, Holmes DR, Lerman A, Barsness GW. Enhanced external counter pulsation for ischemic heart disease: whats behind the curtain? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1918–25.

Lin W, Xion L, Han J, Leung T, Soo Y, Chen X, et al. External counter pulsation augments blood pressure and cerebral flow velocities in ischemic stroke patients with cerebral intracranial large artery occlusive disease. AHA J Stroke. 2012;43:300–1.

Abbottsmith CW, Chung ES, Varricchione T, de Lame PA, Silver MA, Francis GS, et al. Enhanced external counter pulsation improves exercise duration and peak oxygen consumption in older patients with heart failure: a subgroup analysis of the PEECH Trial. Congestive heart fail. 2006;12:307–11.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redón J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–219.

Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, O'Rourke MF, Safar ME, Baou K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with central haemodynamics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1865–71.

Vidal-Petiot E, Ford I, Greenlaw N, Ferrari R, Fox KM, Tardif JC, et al. Cardiovascular event rates and mortality according to achieved systolic and diastolic blood pressure in patients with stable coronary artery disease: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2016;388:2142–252.

Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson S, Callender T, Emberson J, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957–67.

Mancia G, Schumacher H, Redon J, Verdecchia P, Schmieder R, Jennings G, et al. Blood pressure targets recommended by guidelines and incidence of cardiovascular and renal events in the ongoing telmisartan alone and in combination with Ramipril global endpoint trial. Circulation. 2011;124:1727–36.

Sundström J, Arima H, Jackson R, Turnbull F, Rahimi K, Chalmers J, et al. Blood pressure lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2014;384:591–98.

Beck DT, Casey DP, Martin JS, Sadina PW, Braith RW. Enhanced external counterpulsation reduces indices of central blood pressure and myocardial oxygen demand in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Clin Exp Pharmocol Physiolol. 2015;42:315–20.

Sardari A, Hosseini S, Bozorgi A, Lotfi-Tokaldany M, Sadeghian H, Nejatian M. Effects on enhanced external counterpulsation on heart rate recovery in patients with coronary artery disease. J Tehran heart Cent. 2018;13 Suppl 1 :13–17.

Wei W, Jin H, Chen ZW, Zioncheck TF, Yim AP, He GW. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced nitric oxide- and PGI2-dependent relaxation in human internal mammary arteries: a comparative study with KDR and Flt-1 selective mutants. J Cardiovasc Pharm. 2004;44:615–21.

Acknowledgements

We thank Claudia Stelzmann and Xenia Monreal, who provided help during the research, and we thank the patients who supported this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Picard, F., Panagiotidou, P., Wolf-Pütz, A. et al. Individual shear rate therapy (ISRT)—further development of external counterpulsation for decreasing blood pressure in patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease (CAD). Hypertens Res 43, 186–196 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0380-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0380-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of enhanced external counterpulsation versus individual shear rate therapy on the peripheral artery functions

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

May need more comprehensive approach to residual risks in well controlled hypertensive patients

Hypertension Research (2021)