Abstract

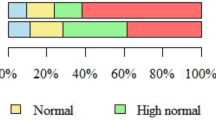

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiac events and stroke. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is known to increase the risk of incident hypertension in adults. Although adiposity has been linked to markers of inflammation, few studies have examined these markers as potential mediators of the association between visceral adiposity and elevated blood pressure. We evaluated sociodemographic, reproductive, and lifestyle risk factors for elevated blood pressure among midlife Singaporean women. A total of 1189 women, with a mean age of 56.3 ± 6.2 years, from the Integrated Women’s Health Program (IWHP) at National University Hospital, Singapore were studied. Hypothesized risk factors and levels of inflammatory markers were examined in relation to systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) using multivariable linear regression models. Prehypertension (SBP 120–139 mmHg and/or DBP 80–89 mmHg) and hypertension (SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg) were observed in 518 (43.6%) and 313 (26.3%) women, respectively. Compared to women in the lowest tertiles, women in the middle and upper tertiles of VAT had 7.1 (95% CI, 4.4, 9.8) mmHg and 10.2 (95% CI, 6.7, 13.7) mmHg higher adjusted SBP, respectively. Nulliparous older women with a lower education level and those with no or mild hot flashes also had a significantly higher adjusted SBP. No significant independent risk factors were observed for DBP. Adjustments for IL-6, TNF-α, and hs-CRP did not attenuate the association between VAT and SBP. In summary, we found an independent positive association between VAT and SBP. Elevated levels of inflammatory markers did not mediate the increase in SBP in women with high VAT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension commonly afflicts midlife women during and after menopause due to the decrease in the vasodilatory effects of endogenous estrogen, increase in rates of obesity, and the high prevalence of depression and anxiety [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Systolic hypertension is a major risk factor for stroke and cardiovascular death [7]. During midlife, women are generally healthy, but previous studies have reported an increase in cardiovascular diseases during this age period [8]. Despite sex differences in the natural history of hypertension, little information is available on risk factors for elevated blood pressure (BP) that are specific to midlife women [6]. Understanding risk factors specific to Asians is of importance, as Asia is home to 60% of the world’s population [9]. In addition, more individuals have elevated BP in Asia than in other regions [10, 11]. A pooled analysis of population-based studies from 200 countries also reported increasing trends for high body mass index (BMI) in Asia [12]. The impact of obesity on BP has also been reported to differ between Asians and Caucasians [13, 14]. Despite several studies conducted with Asian cohorts investigating elevated BP and associated risk factors, the majority have been conducted in older individuals or children, and none, to our knowledge, has examined the mediating role of inflammatory markers in the association of adiposity or VAT with elevated BP in a multiethnic study population [15,16,17,18,19]. Singapore, a multiethnic Asian country, has an aging population, with 40% of residents predicted to be older than 60 by 2050 [20]. An improved understanding of the early risk factors for increased BP in midlife women is critical to reduce rates of cardiovascular disease and stroke.

Adiposity, especially visceral adiposity, is widely recognized as a risk factor for elevated BP and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity [21, 22]. The specific mechanism underlying this association has yet to be determined. Adiposity has been consistently linked to serum markers of inflammation; associations with elevated C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 have been reported in obese individuals [23, 24]. Inflammatory cytokines are released by adipocytes and adipocyte-related macrophages [25], and higher levels of circulating CRP, hs-CRP, and IL-6 are associated with higher BP [26, 27]. However, it is unclear whether inflammatory markers mediate the association of VAT with elevated BP [26, 28, 29]. To address this gap, we used VAT and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to identify risk factors associated with elevated BP levels in midlife women.

Methods

Study design and participants

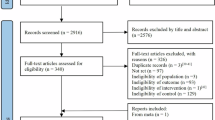

The Integrated Women’s Health Program (IWHP) is a prospective cross-sectional study of midlife Singaporean women aged 45–69 years. Women who had life-threatening conditions were excluded from the study. Recruitment was conducted at the gynecological clinics of National University Hospital (NUH) from 30 September 2014 to 7 October 2016. Data on sociodemographic, reproductive, and other health characteristics were obtained using validated questionnaires. Physical characteristics and functions were objectively measured. The detailed study methodology has been described previously [30]. The Domain-Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group, Singapore, reviewed and approved the study. Out of 2191 women invited to participate in the study, 1201 (54.8%) agreed to participate and provided written informed consent.

Primary outcome measures

In this study, the outcome variables of interest were systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Arm circumference was measured to select the appropriate-sized cuff before proceeding with BP measurement with the participant in a seated position using an OMRON Intellisense oscillometric device (HEM7211) [31,32,33]. The mean values of SBP and DBP were computed from three sets of readings with a 1 min rest between each reading. Hypertension (systolic BP ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg) and prehypertension (systolic BP 120–139 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 80–89 mmHg) were defined according to the classification criteria provided by the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [34]. When the systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings of a participant were in different categories, the higher of the two categories was used.

Studied risk factors

Participants self-identified their race (Chinese, Malay, Indian, or other). Women were categorized as pre menopausal if they had menstruated in the past 3 months and reported no change in menstrual frequency in the past 12 months, peri menopausal if they reported changes in menstrual frequency or 3–11 months of amenorrhea, and post menopausal if they reported amenorrhea for 12 or more consecutive months or had a history of hysterectomy, oophorectomy or both and were older than 49 years at the time of assessment. The included women were asked about past pregnancies, age (categorized as 45–54 years, 55–64 years, or ≥65 years), marital status (married or not), education level (no formal education or primary school, secondary school, or preuniversity or higher), employment status (yes/no), and monthly household income in Singapore dollars (≤7000, ≥3000, or <3000).

Information on the severity of hot flashes was self-reported using the Menopause Rating Scale [35] and dichotomized as “none or mild” or “moderate or severe”. Alcohol intake and smoking (yes/no) were self-declared by the participants. Women were considered diabetic if they responded “yes” to the general medical question “not including during pregnancy, has a health professional ever told you that you have diabetes (high blood sugar)”? Self-reported physical activity was assessed using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire [36]. For the purpose of the present study, women were categorized as spending ≥150 min or <150 min participating in at least moderate-intensity physical activity during a typical week. Participants were asked to report any medications taken in the previous 2 weeks to the study team to complete the medical inventory. The use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was defined as the intake of systemic HRT.

Height and body weight were recorded once and twice, respectively, using a SECA 769 Electronic Measuring Station. Average values for body weight were calculated. BMI was computed as the body weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). We used the World Health Organization revised classification of BMI for Asians: underweight or normal weight (<23.0 kg/m2), overweight (23.0–27.49 kg/m2), or obesity (≥27.5 kg/m2) [37].

Automated software algorithms from dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA, Hologic Discovery Wi, Apex software 4.5) identified the visceral adipose tissue (VAT) by estimating the volume of subcutaneous fat in the abdominal region at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra and subtracting that value from the total abdominal fat volume [38]. A trained operator performed daily calibrations, as suggested by Schoeller et al. [39] with quality control assessments using a standard protocol. In the present study, we analyzed visceral adipose fat cross-sectional area in cm2. The VAT was categorized in tertiles as lower (<88.6 cm2), middle (88.6–131 cm2), or upper (>131 cm2). Handgrip strength was assessed using a hand-held hydraulic dynamometer (Jamar, Bolingbrook, IL) [40]. The average grip strength of two trials of both hands was calculated. Handgrip strength was categorized as <18 or ≥18 kg based on a median split, which is also the cutoff for sarcopenia recommended by the Asian Working Group of Sarcopenia [41]. We used the Short Physical Performance Battery to assess lower body physical performance status; subjects were categorized as having moderate-to-low physical performance if the overall score was <10 and high physical performance if the overall score was ≥10 [42].

We investigated whether the association between VAT and hypertension was mediated by inflammatory markers. Fasting sera were analyzed for levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and hs-CRP at the NUH Referral Laboratory. IL-6 was measured using chemiluminescence immunoassays (ADVIA Centaur Analyzer, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics). TNF-α and hs-CRP were analyzed using colorimetric (Beckman Coulter, Inc., USA) and ELISA assay kits (DRG International, Inc. USA), respectively. To avoid confusion with ongoing infection, outlying values for IL-6 and hs-CRP were excluded [>20.0 pg/mL units for IL-6 (n = 4) and >10.0 mg/L for hs-CRP (n = 43)]. All three inflammatory markers were categorized in tertiles (IL-6 as <1.4, 1.41–2.5, or >2.5 pg/mL; TNF- α as <5.4, 5.5–7.3, or >7.3 pg/mL; hs-CRP as <0.7, 0.71–1.8, or >1.8 mg/L). Many women had identical low levels of inflammatory markers, especially IL-6, resulting in unequal numbers of women.

Statistical analyses

We used multivariable linear regression models to examine the association of VAT with SBP and DBP based on differences in BP means (and their 95% confidence intervals) across tertiles of VAT, accounting for potential confounders postulated to be underlying causes of both adiposity and BP and/or identified in previous studies: ethnicity, menopausal status, parity, age, education, smoking, physical activity, and diabetes [2, 3, 43]. Our base model included ethnicity, menopausal status, parity, age, education, hot flashes, diabetes, smoking, BMI, and physical performance as covariates. To assess the extent to which the observed association between VAT and BP was mediated by markers of inflammation, models were further adjusted (one variable at time) for IL-6 (Model 2), TNF-α (Model 3), and hs-CRP (Model 4). To improve relevance to clinical practice, we also used ordinal logistic regression to evaluate factors independently associated with BP category (normotension, prehypertension, or hypertension) as the dependent variable. Sensitivity analyses with participants not using antihypertensives or HRT were also performed. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software (Version 25, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

General characteristics

Of the 1201 women in the cohort, 12 had incomplete data on BP, leaving 1189 subjects for analysis. Subjects were mainly post menopausal (71.8%), with a mean ± SD age of 56.3 ± 6.2 years and a mean BMI of 24.1 ± 4.4 kg/m2. Prehypertension (SBP 120–139 mmHg and/or DBP 80–89 mmHg) was observed in 43.6% (n = 518), and hypertension (SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg) was observed in 26.3% (n = 313) of our cohort. Table 1 shows the crude (unadjusted) systolic and diastolic blood pressures according to the categorized risk factors. Postmenopausal status, older age (55–64 years and ≥65 years), lower education (secondary or no formal or primary), unemployment, lower household income, absent/mild (compared to moderate/severe) hot flashes, diabetes, high BMI (overweight or obese), higher VAT (middle or upper tertile), low physical performance status, higher TNF-α, and hs-CRP (middle or upper tertile) were all associated with higher SBP. Ethnicity, parity, marital status, smoking, alcohol intake, self-reported physical activity, handgrip strength, and IL-6 were not significantly associated with SBP. Nulliparity, moderate/severe hot flashes, diabetes, high BMI (obese or overweight), and higher IL-6 tertiles were crudely associated with higher DBP.

Table 2 shows the adjusted differences in the means of SBP and DBP according to the categorized risk factors. Of note, women in the middle and upper tertiles of VAT had 7.1 (95% CI, 4.4, 9.8) and 10.2 (95% CI, 6.7, 13.7) mmHg higher SBP, respectively, than women in the lower tertile, after adjustment for all covariates (Model 1). As also shown in Table 2, adjustments for the three inflammatory markers did not attenuate the association of VAT with SBP (Model 2). Women with one or two children had a 3.2 (95% CI, 5.9, 0.4) mmHg lower SBP than nulliparous women. Women 55–64 years and those ≥65 years had 5.3 (95% CI, 2.7, 7.9) and 7.6 (95% CI, 3.9, 11.5) mmHg higher mean SBP, respectively, than women 45–54 years. Women with no formal or primary education and those with a secondary education had 4.5 (95% CI, 1.4, 7.5) and 3.9 (95% CI, 1.7, 6.1) mmHg higher SBP, respectively, than women who completed a university-level education. No significant independent risk factors were observed for DBP.

Supplementary Table 1 shows the findings of the analyses of hypertension as an ordinal outcome using ordinal logistic regression. Higher VAT tertile, older age, lower educational status, and use of antihypertensive drugs (39% in our cohort) were significantly associated with a higher BP category. A greater number of children and moderate or severe hot flashes were also associated with BP category but did not achieve statistical significance. As shown in Supplementary Table 2, where the analysis was restricted to participants not using antihypertensive medications, overweight BMI and the highest tertile of hs-CRP were associated with lower and higher SBP, respectively. The previously observed associations of lower SBP with 1 or 2 previous children (vs. nulliparous) and with moderate or severe hot flashes were no longer significant, whereas the associations of higher SBP with higher tertiles of VAT, older age, and lower educational status persisted. In other words, the use of antihypertensive drugs in our cohort did not affect the association we observed between VAT and SBP. No notable associations were observed with DBP. In addition, sensitivity analysis restricted to participants not using HRT (Supplementary Table 3a) and when the analysis was adjusted for HRT use (2% in our cohort) (Supplementary Table 3b) revealed results very similar to those of the primary analyses.

Discussion

In this large prospective cross-sectional multiethnic cohort of midlife women, we assessed VAT using direct measurements by DXA instead of relying on surrogate markers such as waist circumference or BMI. Higher visceral adiposity was associated with elevated mean SBP. Our data also show that parous women and women reporting moderate or severe hot flashes had lower SBP, even after controlling for the well-established associations of SBP with age and educational attainment. The association we observed between VAT and SBP was not mediated by markers of inflammation (IL-6, TNF-a, or hs-CRP). In other words, increased levels of inflammatory markers in women with higher visceral adiposity did not “explain” the elevated mean SBP in women with higher VAT.

Positive associations between VAT and SBP [44,45,46] are well known, as are the associations between high levels of circulating CRP, hs-CRP, and IL-6 and the risk of developing hypertension [47]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are few studies on the mediating role of inflammatory markers in the association between VAT and BP in midlife multiethnic Asian women. The three other studies comprised an elderly community-dwelling population, examined only the risk factors related to dietary intake and assessed a younger homogenous sample of Chinese individuals [15, 48, 49]. Our finding that the inflammatory biomarkers IL-6, TNF-α and hs-CRP did not appear to mediate the association between VAT and SBP was surprising. It is possible that a longer exposure to adiposity accumulation may be required for this mediation to manifest [50, 51]. Alternative biological mechanisms, such as regulation via aldosterone-dependent mechanisms [52], as reported in an experimental study using female mice [53], may also underlie the associations we observed. Additionally, epidemiologic evidence suggests that leptin and adiponectin, important products of visceral adipocytes, are possible mediators of adiposity-related hypertension [54]. Unfortunately, we did not measure these adipokines.

We also observed a lower mean SBP in women with 1–2 children than in nulliparous women, even after adjustment for adiposity, age, education and hot flashes. This may be explained by the cardiovascular adaptations that occur during pregnancy, such as reduced vascular resistance and increased arterial compliance persisting even into postreproductive years, as reported by the HUNT study and the 2010 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [55,56,57]. An inverse association was observed between levels of education and SBP. This finding is supported by findings from a recent large population of eight studies (n = 28,891) among Black, White and Hispanic individuals [58]. Evidence from a longitudinal study and a meta-analysis points to individuals with a higher level of education having access to healthcare and social support, awareness of hypertension, and healthier lifestyle as potential explanations [59, 60].

The association between hot flashes and BP is controversial. In our study, women with moderate or severe hot flashes had lower SBP than those with no or mild flashes. The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation reported that American women with vasomotor symptoms were more likely to develop hypertension than women without vasomotor symptoms [61]. Other studies indicate no significant differences in mean BP between women with and without hot flashes [62]. Menopausal transition and ethnic differences in our cohort may contribute to this contrasting finding.

Using BP categories as the outcome, we observed similar findings as those based on continuous BP. In previous studies, SBP but not DBP has been associated with a stronger risk of cardiovascular events and cognitive decline in middle-age and older adults [63,64,65]. Despite the established vascular protective effect of estrogen via anti-inflammatory pathways [66], the results of our sensitivity analyses were similar to those of the primary analysis. This could be explained by the very few women who were taking estrogen. Therefore, no bias or effect modification of the use of hormonal treatment was observed in our cohort.

The limitations of our study include its cross-sectional design, although SBP seems unlikely to affect abdominal (or overall) adiposity. Additionally, our study was conducted in generally healthy midlife women of Chinese, Malay and Indian ethnicity and therefore may not be generalizable to women of other ages or ethnicities or those living in nonurban environments. We also acknowledge that residual confounding due to other unmeasured factors related to both VAT and SBP might have biased our results. The strengths of our study include a large, deeply phenotyped sample of midlife women; the representation of ethnicities comprising 40% of the world’s population; and the use of visceral adiposity as measured objectively by DXA rather than through the use of surrogate measures. Finally, previous studies have not, to our knowledge, investigated the potential mediating role of inflammatory markers in an Asian population. The Dallas Heart Study included only Blacks, Caucasians and Hispanics [43]. Previous studies on hypertension in Singapore either focused on awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension or assessed dietary risk factors for hypertension in older age groups [48, 67].

High SBP is one of the five leading risk factors for the global burden of disease among women and accounted for 10.4 million deaths in 2017 [7]. Greater appreciation of modifiable risk factors for systolic hypertension, such as adiposity, parity and education, may be incorporated into public health campaign efforts to increase awareness and to encourage lifestyle modification as preventive strategies to help slow the epidemic of adiposity-induced hypertension [68].

In conclusion, we observed a strong association between visceral adiposity and systolic hypertension. Elevated levels of inflammatory markers did not mediate that association. Future studies are required to elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying the association to better understand the pathophysiology of obesity-induced hypertension.

References

Wenger NK, Ferdinand KC, Merz CNB, Walsh MN, Gulati M, Pepine CJ. Women, hypertension, and the systolic blood pressure intervention trial. Am J Med. 2016;129:1030–6.

Gudmundsdottir H, Høieggen A, Stenehjem A, Waldum B, Os IJ. Hypertension in women:latest findings and clinical implications. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2012;3:137–46.

Collins P, Rosano G, Casey C, Daly M, Gambacciani M, Hadji P, et al. Management of cardiovascular risk in the peri-menopausal woman: a consensus statement of European cardiologists and gynaecologists. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2028–40.

Jones HJ, Minarik PA, Gilliss CL, Lee KA. Depressive symptoms associated with physical health problems in midlife women: a longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:301–9.

Ganasarajah S, Poromaa IS, Thu WP, Kramer MS, Logan S, Cauley JA, et al. Objective measures of physical performance associated with depression and/or anxiety in midlife Singaporean women. Menopause. 2019;26:1045–51.

Ahmad A, Oparil S. Hypertension in women: recent advances and lingering questions. Hypertension. 2017;70:19–26.

Stanaway JD, Afshin A, Gakidou E, Lim SS, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1923–94.

Harlow SD, Derby CA. Women’s midlife health: why the midlife matters. Womens Midlife Health. 2015;1:5.

United Nations Population Fund U. Population Trends. 2019. https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/node/15207. Accessed 18 Mar 2020.

Collaboration NRF. Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19· 1 million participants. Lancet. 2017;389:37.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Contributions of mean and shape of blood pressure distribution to worldwide trends and variations in raised blood pressure: a pooled analysis of 1018 population-based measurement studies with 88.6 million participants. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:872–83.

Collaboration NRF. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1377–96.

Ishikawa Y, Ishikawa J, Ishikawa S, Kayaba K, Nakamura Y, Shimada K, et al. Prevalence and determinants of prehypertension in a Japanese general population: the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1323–30.

Katsuya T, Ishikawa K, Sugimoto K, Rakugi H, Ogihara T. Salt sensitivity of Japanese from the viewpoint of gene polymorphism. Hypertens Res. 2003;26:521–5.

Seow LSE, Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Chong SA. Hypertension and its associated risks among Singapore elderly residential population. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;6:125–32.

Lin YA, Chen YJ, Tsao YC, Yeh WC, Li WC, Tzeng IS, et al. Relationship between obesity indices and hypertension among middle-aged and elderly populations in Taiwan: a community-based, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031660.

Otani K, Haruyama R, Gilmour S. Prevalence and correlates of hypertension among Japanese adults, 1975 to 2010. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1645.

Park JB, Kario K, Wang J-G. Systolic hypertension: an increasing clinical challenge in Asia. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:227–36.

Bonafini S, Giontella A, Tagetti A, Montagnana M, Benati M, Danese E, et al. Markers of subclinical vascular damages associate with indices of adiposity and blood pressure in obese children. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:400–10.

Malhotra R, Bautista MAC, Müller AM, Aw S, Koh GC, Theng YL, et al. The aging of a young nation: population aging in Singapore. Gerontologist. 2019;59:401–10.

Dimitriadis K, Tsioufis C, Mazaraki A, Liatakis I, Koutra E, Kordalis A, et al. Waist circumference compared with other obesity parameters as determinants of coronary artery disease in essential hypertension: a 6-year follow-up study. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:475–9.

Haraguchi N, Koyama T, Kuriyama N, Ozaki E, Matsui D, Watanabe I, et al. Assessment of anthropometric indices other than BMI to evaluate arterial stiffness. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1599–605.

Després J-P, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881.

Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote LJ. Obesity and C‐reactive protein in various populations: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14:232–44.

Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2548–56.

Jayedi A, Rahimi K, Bautista LE, Nazarzadeh M, Zargar MS, Shab-Bidar S. Inflammation markers and risk of developing hypertension: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Heart. 2019;105:686–92.

Buford TW. Hypertension and aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;26:96–111.

Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. Obesity-induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res. 2015;116:991–1006.

Lyon CJ, Law RE, Hsueh WA. Minireview: adiposity, inflammation, and atherogenesis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2195–200.

Thu WPP, Logan SJS, Lim CW, Wang YL, Cauley JA, Yong EL. Cohort profile: the Integrated Women’s Health Programme (IWHP): a study of key health issues of midlife Singaporean women. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:389–90.

Topouchian J, Agnoletti D, Blacher J, Youssef A, Ibanez I, Khabouth J, et al. Validation of four automatic devices for self-measurement of blood pressure according to the international protocol of the European Society of Hypertension. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:709.

Price AJ, Crampin AC, Amberbir A, Kayuni-Chihana N, Musicha C, Tafatatha T, et al. Prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, and cascade of care in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional, population-based study in rural and urban Malawi. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:208–22.

Ong HL, Abdin E, Seow E, Pang S, Sagayadevan V, Chang S, et al. Prevalence and associative factors of orthostatic hypotension in older adults: Results from the Well-being of the Singapore Elderly (WiSE) study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;72:146–52.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–71.

Schneider H, Behre H. Contemporary evaluation of climacteric complaints: its impact on quality of life. In: Schneider HPG, editor. Hormone replacement therapy and quality of life. London, New York, Washington, Boca Raton: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 2002. p. 45–61.

Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:790–804.

WHO, Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157.

Bazzocchi A, Ponti F, Albisinni U, Battista G, Guglielmi G. DXA: Technical aspects and application. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:1481–92.

Schoeller DA, Tylavsky FA, Baer DJ, Chumlea WC, Earthman CP, Fuerst T, et al. QDR 4500A dual-energy X-ray absorptiometer underestimates fat mass in comparison with criterion methods in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1018–25.

Abizanda P, Navarro JL, García-Tomás MI, López-Jiménez E, Martínez-Sánchez E, Paterna G. Validity and usefulness of hand-held dynamometry for measuring muscle strength in community-dwelling older persons. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54:21–7.

Chen L-K, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:300–7.e2.

Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Nevitt MC, Kritchevsky SB, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, et al. Measuring higher level physical function in well-functioning older adults: expanding familiar approaches in the Health ABC study. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M644–9.

Chandra A, Neeland IJ, Berry JD, Ayers CR, Rohatgi A, Das SR, et al. The relationship of body mass and fat distribution with incident hypertension: observations from the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:997–1002.

Park S-Y, Karki S, Saggese SM, Zuriaga MA, Carmine B, Hess D, et al. Angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction of the visceral adipose tissue vasculature is linked to systemic hypertension in obesity. FASEB J. 2017;31:684.6.

Elffers TW, de Mutsert R, Lamb HJ, De Roos A, Van Dijk JK, Rosendaal FR, et al. Body fat distribution, in particular visceral fat, is associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in obese women. PloS ONE. 2017;12:e0185403.

Oikonomou EK, Antoniades C. The role of adipose tissue in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:83–99.

Kunutsor SK, Laukkanen JA. Should inflammatory pathways be targeted for the prevention and treatment of hypertension? Heart. 2019;105:665–7.

Chei C-L, Loh JK, Soh A, Yuan J-M, Koh W-P. Coffee, tea, caffeine, and risk of hypertension: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:1333–42.

Zheng C-J, Dong Y-h, Zou Z-y, Lv Y, Wang ZH, Yang ZG, et al. Sex difference in the mediation roles of an inflammatory factor (hsCRP) and adipokines on the relationship between adiposity and blood pressure. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:903.

Skinner AC, Steiner MJ, Henderson FW, Perrin EM. Multiple markers of inflammation and weight status: cross-sectional analyses throughout childhood. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e801–9.

Brown DE, Mautz WJ, Warrington M, Allen L, Tefft HA, Gotshalk L, et al. Relation between C‐reactive protein levels and body composition in a multiethnic sample of school children in Hawaii. Am J Hum Biol. 2010;22:675–9.

Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:85.

Huby A-C, Otvos L Jr, Belin de Chantemèle EJ. Leptin induces hypertension and endothelial dysfunction via aldosterone-dependent mechanisms in obese female mice. Hypertension. 2016;67:1020–8.

Kim DH, Kim C, Ding EL, Townsend MK, Lipsitz LA. Adiponectin levels and the risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2013;62:27–32.

Haug EB, Horn J, Markovitz AR, Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, et al. The impact of parity on life course blood pressure trajectories: the HUNT study in Norway. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33:751–61.

Jang M, Lee Y, Choi J, Kim B, Kang J, Kim Y, et al. Association between parity and blood pressure in Korean Women: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2010–2012. Korean J Fam Med. 2015;36:341–8.

Li W, Ruan W, Lu Z, Wang D. Parity and risk of maternal cardiovascular disease: A dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;26:592–602.

Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Jiang R, Huffman KM, Kraus WE, Singh A, et al. Systolic blood pressure and socioeconomic status in a large multi-study population. SSM Popul Health. 2019;9:100498.

Vathesatogkit P, Woodward M, Tanomsup S, Hengprasith B, Aekplakorn W, Yamwong S, et al. Long-term effects of socioeconomic status on incident hypertension and progression of blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1347–53.

Leng B, Jin Y, Li G, Chen L, Jin N. Socioeconomic status and hypertension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2015;33:221–9.

Jackson EA, El Khoudary SR, Crawford SL, Matthews K, Joffe H, Chae C, et al. Hot flash frequency and blood pressure: data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Womens Health. 2016;25:1204–9.

Brown DE, Sievert LL, Morrison LA, Rahberg N, Reza A. The relation between hot flashes and ambulatory blood pressure: the Hilo Women’s Health Study. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:166.

Fitchett G, Powell LH. Daily spiritual experiences, systolic blood pressure, and hypertension among midlife women in SWAN. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:257–67.

Rosenblad A. A comparison of blood pressure indices as predictors of all-cause mortality among middle-aged men and women during 701,707 person-years of follow-up. J Hum Hypertens. 2018;32:660–7.

Gottesman RF, Schneider AL, Albert M, Alonso A, Bandeen-Roche K, Coker L, et al. Midlife hypertension and 20-year cognitive change: the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1218–27.

Gersh FL, Lavie CJ. Menopause and hormone replacement therapy in the 21st century. Heart. 2020;106:479–81.

Wu Y, Tai ES, Heng D, Tan CE, Low LP, Lee J. Risk factors associated with hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in a multi-ethnic Asian population. J Hypertens. 2009;27:190–7.

Ok Ham K, Jeong Kim B. Evaluation of a cardiovascular health promotion programme offered to low‐income women in Korea. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1245–54.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants and study coordinators of IWHP. They are also grateful to Ms Tan Sze Yee from the Department of Orthopedic Surgery for conducting whole body DXA scans and to Dr Li Jun for grant management and the procurement of study materials.

Funding

This study was partially funded by a Singapore National Medical Research Council Grant (Number: NMRC/CSA-SI/0010/2017) provided to ELY.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thu, W.P.P., Sundström-Poromaa, I., Logan, S. et al. Blood pressure and adiposity in midlife Singaporean women. Hypertens Res 44, 561–570 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00600-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00600-2