Abstract

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Recent studies have identified an association between low vitamin D levels and hypertension. We investigated the association between vitamin D levels and hypertension in the general population. We recruited 400 hypertensive subjects and compared them with 400 age- and sex-matched normotensive subjects. This study was carried out at Yashoda Hospital, Hyderabad, India from January 2015 to December 2017. Both groups underwent risk factor evaluation, estimation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, and C-reactive protein (CRP) and liver function tests. Out of the 400 hypertensive subjects, 164 (40.2%) had serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency, compared with 111 (27.7%) normotensive subjects (p = 0.0001). Deficiency of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in hypertensive subjects was significantly associated with CRP positivity, low levels of mean serum calcium, low levels of mean serum phosphorous, high levels of mean alkaline phosphatase (p < 0.0001), and abnormal alanine transaminase (ALT) (p = 0.0015) compared with the same parameters in the normotensive subjects. After adjustment in the multiple logistic regression analysis, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency (odds: 1.78; 95% CI: 1.31–2.41), CRP positivity (odds: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.48–2.32) and abnormal ALT (odds: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.98–1.94) were significantly associated with hypertension. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency was significantly associated with hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a modifiable risk factor risk factor that is associated with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease and mortality [1, 2]. Approximately 90–95% of cases result from primary hypertension with many etiological factors, such as age, race, family history, obesity, lifestyle, use of tobacco, high salt intake, stress, consumption of alcohol in large quantities, and nonspecific lifestyle and genetic factors [3, 4]. Worldwide, nearly one billion adults (25%) are suffering from primary hypertension, and the prevalence may increase by 29% by 2025 [3, 4]. Recent studies have established an association of serum vitamin D deficiency with primary hypertension [5]. Vitamin D is important for the human body to maintain a balance between calcium and phosphorus. Vitamin D deficiency can cause weakness, increased bone loss, and low levels of bone mineralization [6]. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is a marker of vitamin D status in the human body [7]. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency and primary hypertension in south Indian subjects. Very limited studies are available from the Indian subcontinent.

Materials and methods

We prospectively enrolled 400 hypertensive subjects and age- and sex-matched normotensive subjects at the Yashoda Hospital Hyderabad. Yashoda Hospital is a tertiary care center that serves the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana in south India. The study period was from January 2015 to December 2017, and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. We enrolled both groups in three seasons (summer season: March to mid-June, rainy season: mid-June to October and winter season: November to February).

Selection of cases

Hypertensive subjects were identified by systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg, or subjects with self-reported hypertension. Incident hypertension was considered a recently developed hypertension with SBP ≥140 mmHg and DBP ≥90 mmHg at baseline and three consecutive visits or based on the Joint National Committee VIII criteria [2].

Selection of normotensive (controls)

Normotensive subjects were defined as those with SBP ≤120 mmHg and DBP ≤80 mmHg at baseline and three consecutive visits without the use of antihypertension medications.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Hypertensive subjects older than 40 years and age- and sex-matched normotensive subjects were included in the study. Individuals with vitamin D supplementation, tuberculosis, any bone diseases, chronic kidney disease, muscle weakness, secondary hypertension, steroids, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, chronic liver disease, anti-epileptic drug use, cholestyramine drugs, antacid medications, orlistat and osteoporosis drugs or white coat syndrome were excluded from the study for both groups (hypertensive and normotensive).All subjects’ data were collected through face-to-face interviews, and present and past medical histories were collected. A standardized questionnaire was adapted from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [7]. Subjects in both groups underwent fasting blood sugar, lipid profile, liver function, serum calcium, alkaline phosphatase, phosphorous, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and C-reactive protein (CRP) analyses.

Risk factor analysis

Hypertension was defined as ≥140 mmHg SBP and ≥90 mmHg DBP or the use of antihypertension medications, diabetes was diagnosed if subjects were taking antidiabetic medications, dyslipidemia was considered in subjects having ≥200 mg/dL or who were on statins, alcoholism was defined as alcohol consumption >50 g/day, smokers were defined as those reporting a daily smoking habit, ex-smokers and occasional smokers were categorized as nonsmokers [4, 8, 9], CRP positivity was considered when the CRP level was ≥0.6 mg/dL [10], and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels ≥70 U/L and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels ≥47 U/L were treated as abnormal levels [11].

Blood pressure monitoring

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring was performed in cases and controls. Blood pressure was measured by a trained physician with a mercury sphygmomanometer on the right arm with the participant in a seated position after 5 min of rest.

Assessment of 25-hydroxyvitamin D

In our laboratory, we used a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay with an automated instrument for the estimation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and the sensitivity and specificity of the instrument were 53% and 90.5%, respectively. Our lab manual and the current literature state that serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D values ≤20 ng/mL indicate deficiency and that values ≥20.1 ng/mL are normal [12, 13].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Inc. (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 21.0 software. The mean and standard deviation were calculated. The paired t-test was performed to assess differences in continuous variables. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed before and after adjustment for potential confounders (sex, dyslipidemia, CRP positivity, obesity, diabetes, alcoholism, and smoking). We assessed the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to identify the cut-off value of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which may predict the outcome values. All tests were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 400 hypertensive subjects and 400 normotensive subjects were included in the study. Men accounted for 63.7% of the hypertensive patients and 63.7% of the control subjects. The mean age was similar in both groups (52.4 ± 4.43 years in the hypertensive subjects and 53.1 ± 5.12 years in the normotensive subjects). Hypertensive subjects had a significantly higher proportion of vitamin D deficiency (p < 0.0001), low mean serum calcium (p < 0.0001), elevated mean parathyroid hormone (PTH) (p < 0.0001), low mean serum phosphorous (p < 0.0001), abnormal ALT (p = 0.0015), abnormal AST (p = 0.0056), and high mean alkaline phosphatase (p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

We compared various factors based on vitamin D status in hypertensive subjects. Long mean duration of hypertension (p = 0.02), elevated mean SBP (p < 0.0001) and mean DBP (p < 0.0001), abnormal ALT (p = 0.0064), and abnormal AST (p = 0.0034) were significantly associated with vitamin D deficiency (Table 2).

After multivariate analysis, we established that the major predictors of hypertension were serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (odds 1.78; 95% CI: 1.31–2.41), abnormal ALT (odds: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.98–1.94), abnormal AST (odds: 1.1; 95% CI: 0.89–1.72), and CRP positivity (odds 1.48; 95% CI: 1.18–2.12) (Table 3).

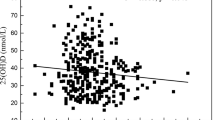

We performed an ROC curve to identify the cut-off value of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which may be used to predict primary hypertension. The maximum area under the curve was 0.71 with a 25-hydroxyvitamin D value of 18 ng/ml with a sensitivity of 73.4 (61.7–82.1) and specificity 54.6 (51.4–65.3) (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

In the present study, a low mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level was significantly more common in hypertensive subjects than in controls (20.5 ± 6.3 ng/mL vs 26.6 ± 9.0 ng/mL) (p < 0.0001), and our findings were in agreement with others [5, 14,15,16,17]. Akbari found a mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D value of 24.5 ± 19.4 ng/mL for patients and 15.3 ± 12.2 ng/mL for controls [14]. Ahmad et al. showed mean vitamin D levels of 24.1 ± 16.3 ng/mL in cases and 39.8 ± 11.1 ng/mL in controls [15]. Holick found vitamin D levels of 26.4 ± 4.9 ng/mL in cases and 36 ± 5 ng/mL in controls [16]. Priya et al. found vitamin D levels of 15.15 ± 12.51 ng/mL in cases and 33.59 ± 16.69 ng/mL in controls in her study [5]. Gowda and Khan showed a mean value of vitamin D 19.9 of ng/mL in cases and 32.2 ng/mL in controls [17].

A recent study observed a rate of 50% deficiency in cases and 33.3% deficiency in control subjects [18]. In our study, we found 40.2% deficiency in hypertensive subjects and 27.7% deficiency in controls, which is similar to the findings noted by others [5]. African Americans have a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among hypertension subjects due to lower serum vitamin synthesis due to skin pigmentation [19]. In the current study, we established that serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency was independently associated with hypertension among the subjects (odds: 1.78; 95% CI: 1.31–2.41); our findings were supported by others [20,21,22,23]. Qi et al. noted the same finding in his study (odds: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.01–1.48) [20]. Forman et al. (odds: 2.67; 95% CI: 1.05–6.79) [20] and Jode et al. also noted similar findings (odds: 1.22; 95% CI: 0.87–1.72) [23]. Pittas et al. established that the risk increased by 6.1 times in men and 2.6 times in women [22].

Several studies have shown possible mechanisms that link vitamin D to hypertension; vitamin D negatively regulates the renin–angiotensin system and is associated with endothelial vasodilator dysfunction [20]. Vitamin D mediates the activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and causes hypertension [24]. However, few studies have found that serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is not significantly associated with hypertension [25, 26].

Systolic BP

In the present study, we found that high mean SBP was significantly associated with 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency hypertension 151.8 ± 18.2 mmHg and controls 141.2 ± 10.2 mmHg (p < 0.0001), a similar findings noted by others [18, 27, 28].

Kota et al. demonstrated a mean SBP of 173.7 ± 18.8 mmHg among subjects in his study [27]. Qureshi et al. noted that elevated SBP was significantly associated with vitamin D deficiency [18]. Duprez et al. noted that low levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D were associated with SBP [28]. Randomized studies have explored the effects of calcium with vitamin D 400 IU supplementation over a period of time, and SBP was significantly reduced [18, 29].

Diastolic BP

In the current study, we demonstrated that the mean DBP was significantly associated with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in hypertensive subjects (97.4 ± 8.4 mmHg vs 89.5 ± 7.5 mmHg, p < 0.0001). Similar results were reported by Kota et al. (mean 108.1 ± 11.8) [27]. Studies have demonstrated that vitamin D supplementation can reduce DBP [29, 30]. However, a recent study noted no significant reduction in diastolic pressure as a result of vitamin D supplementation [3].

Seasonal variation

In our study, we found that serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D was not significantly associated with hypertension, and these findings were supported by previous studies [6, 7, 9, 10, 12]. However, few studies have found a significant association with seasonal variations [18, 31].

Parathyroid hormone

In the present study, we found that elevated PTH was significantly associated with hypertension and that PTH was not significantly associated with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in hypertensive subjects. Our findings were in agreement with others [26]. In contrast, few studies have noted that high levels of PTH and vitamin D deficiency are independently associated with hypertension [32].

Abnormal transaminase enzyme levels

Elevated liver enzymes (ALT and AST) are indicators of liver disease and the risk of high blood pressure [11, 33]. In the present study, we found that abnormal ALT and AST enzymes were significantly associated with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in hypertensive subjects (p = 0.0015, and p = 0.0034). Similar findings were found in other studies. Zelber-Sagi et al. noted that the elevated ALT levels were associated with vitamin D deficiency in the general population [34], and Bahrynian et al. noted in his study that elevated liver enzymes (ALT and AST) were associated with vitamin D deficiency in adolescents with hypertension [35].

The current study established abnormal ALT (odds: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.98–1.94) as being independently associated with hypertension, but the same results were not found for AST (odds: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.59–1.32); these findings are in agreement with others [36]. However, a few studies have noted no significant association between vitamin D and elevated ALT and AST enzymes [37, 38].

C-reactive protein

In the current study, we established that CRP was significantly positively associated with hypertension compared with the CRP levels of normotensive subjects, and our findings were in agreement with others [39,40,41]. Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated elevations in inflammatory markers among individuals with high blood pressure [39, 41]. In the present study, we established CRP positivity as an independent risk factor for hypertension (odds: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.18–2.12), which was supported by previous studies [42].

CRP functions as a pro-atherosclerotic factor by upregulating angiotensin type 1 receptor expression [39]. Hypertension may lead to inflammatory stimuli in the vessel wall and support the protection of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6) [43]. CRP decreases the production of nitric oxide and increases plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and endothelin-1 activity in endothelial cells, and promotes vasoconstriction, platelet activation, and thrombosis formation. In addition, CRP upregulates angiotensin receptor-1 and increases angiotensin-II activity and increases blood pressure [40]. However, a few studies have found no significant relationship between CRP positivity and hypertension [44].

Pitfalls of study

The strengths of this study include that the laboratory tests of both groups of subjects (hypertensive and normotensive) were performed in one lab. We applied multiple logistic regression analysis before and after adjustment for confounders to identify independent associations and performed ROC curves. The limitations of the study include that we were unable to analyze the presence of metabolic syndrome, the prevalence of postmenopausal women, the estimation of sun exposure, physical activity, and the dietary intake of vitamin D in either group. In our study, we measured aminotransferase levels one time in both groups.

Conclusion

In the present study, we established that low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and CRP positivity were independently associated with hypertension in south Indian patients. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency was associated with a 1.5-times higher risk, positive CRP was associated with a 1.4-times higher risk, and abnormal ALT was associated with a 1.2-times higher risk for hypertension. Larger multicenter randomized control studies are required to determine the potential role of these findings in hypertension management to decrease the public heath burden.

References

Hernandorena I, Duron E, Vidal JS, Hanon O. Treatment options and considerations for hypertensive patients to prevent dementia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:989–1000.

Bandaru VCS, Laxmi V, Neeraja M, Alladi S, Meena AK, Borgohain R, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies in various subtypes ischemic stroke in Indian patients. J Neurological Sci. 2008;272:115–22.

Mehta V, Agarwal S. Does vitamin D deficiency lead to hypertension? Cureus. 2017;9:e1038.

Zhang D, Zeng J, Miao X, Liu H, Ge L, Huang W, et al. Glucocorticoid exposure induces preeclampsia via dampening 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:104–11.

Priya S, Singh A, Pradhan A, Himanshu D, Agarwal A, Mehrotra S. Association of vitamin D and essential hypertension in a north Indian population cohort. Heart India. 2017;5:7–11.

Chaudhuri JR, Mridula KR, Lingaiah A, Balaraju B, Bandaru VCS. Association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and type 2 diabetes: a case control study. Iran J Diabetes Obes. 2014;6:47–55.

Chaudhuri JR, Mridula KR, Alladi S, Anamika A, Umamahesh U, Balaraju B, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in ischemic stroke and subtypes in Indian patients. J Stroke. 2014;16:44–50.

Bandaru VCS, Boddu DB, Rukmini KM, Akhila B, Alladi S, Laxmi V, et al. Outcome of chlamydia pneumoniae associated acute ischemic stroke in elderly patients: a case control study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:120–3.

Chaudhuri JR, Mridula KR, Kishore CR, Balaraju B. Bandaru VCSS association of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in pediatric epilepsy: a study from tertiary care center. Iran J Child Neurol. 2017;11:48–56.

Chaudhuri JR, Mridula KR, Keerthi AS, Prakasham PS, Balaraju B, Bandaru VCS. Association between chlamydia pneumoniae and migraine: a study from a tertiary center in India. J Oral Fac Pain Headache. 2016;30:150–5.

Bandaru VCSS, Chaudhuri JR, Lalitha P, Reddy SN, Misra PK, Balaraju B, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in non-diabetes subjects: a study from south India. Egypt J Intern Med. 2019;31:92–8.

Chaudhuri JR, Mridula KR, Umamahesh U, Balaraju B, Bandaru VCS. Association of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and Carotid atherosclerosis in Indian population: a from south India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2017;20:242–7.

Chaudhuri JR, Mridula KR, Umamash, Balaraju B, Bandaru VCSS. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in multiple sclerosis: a study from south India. Neurol Disord Stroke Int. 2018;1:1–6.

Akbari R, Adelani B, Ghadimi R. Serum vitamin D in hypertensive patients versus healthy controls is there an association? Casp J Intern Med. 2016;7:168–72.

Ahmad YK, El-Ghamry EM, Tawfik S, Atia WM, Keder MM, Abd-EL Kader SA. Assessment of vitamin D status in patients with essential hypertension. Egyptian J Hosp Med. 2018;72:4434–8.

Holick M. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmunediseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1678S–1688S.

Gowda HR, Khan MA. A study on plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels as a risk factor in primary hypertension. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2015;2:4267–77.

Qureshi D, Kausar H. A study on plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels as a risk factor for in primary hypertension. Int J Biol Pharm Allied Sci. 2014;3:557–66.

Rostand SG. Vitamin D, blood pressure, and African Americans: toward a unifying hypothesis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1697–703.

Qi D, Nie XL, Wu S, Cai J. Vitamin D and hypertension: prospective study and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0174298.

Forman JP, Giovannucci E, Holmes MD, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Tworoger SS, Willett WC, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of incident hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1063–9.

Pittas AG, Dawson-Hughes B, Li T, Van Dam RM, Willett WC, Manson JE, et al. Vitamin D and calcium intake in relation to type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:650–6.

Jorde R, Figenschau Y, Emaus N, Hutchinson M, Grimnes G. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are strongly related to systolic blood pressure but do not predict future hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:792–8.

Ke L, Mason RS, Kariuki M, Mpofu E, EBrock K. Vitamin D status and hypertension: a review. Integr Blood Press Control. 2015;8:13–35.

Caro Y, Negrón V, Palacios C. Association between vitamin D levels and blood pressure in a group of Puerto Ricans. P R Health Sci J. 2012;31:123–29.

Li L, Yin X, Yao C, Zhu X, Wu X. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone and their associations with hypertension in a Chinese population. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e43344.

Kota SK, Jammula S, Meher LK, Panda S, Tripathy PR, Modi KD, et al. Renin-angiotensin system activity in vitamin D deficient, obese individuals with hypertension: an urban Indian study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011; Suppl 4:S395–401.

Duprez D, de Buyzere M, de Backer T, Clement D. Relationship between vitamin D a peripheral circulation in moderate arterial primary Hypertension. Blood Press. 1994;3:389–93.

Afzal S, Nordestgaard BG. Low vitamin D and hypertension: a causal association? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:682–4.

Chen WR, Liu ZY, Shi Y, Yin DW, Wang H, Sha Y, et al. Vitamin D and nifedipine in the treatment of Chinese patients with grades I-II essential hypertension: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235:102–9.

Hagenau T, Vest R, Gissel TN, Poulsen CS, Erlandsen M, Mosekilde L, et al. Global vitamin D levels in relation to age, gender, skin pigmentation and latitude: an ecologic meta-regression analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:133–40.

Zhao G, Ford ES, Li C, Kris-Etherton PM, Etherton TD, Balluz LS. Independent associations of serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone with blood pressure among US adults. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1821–8.

Cheung BM, Ong KL, Tso AW, Cherny SS, Sham PC, Lam TH, et al. Gamma-glutamyl transferase level predicts the development of hypertension in Hong Kong Chinese. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:1326–31.

Zelber-Sagi S, Zura R, Thurm T, Goldstein A, Ben-Assuli O, Chodick G, et al. Serum vitamin D is independently associated with unexplainedelevated ALT only among non-obese men in the general population. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18:578–84.

Bahrynian M, Qorbani M, Motlagh ME, Heshmat R, Khadmian M, Kelishadi R. Association of serum 25‑hydroxyvitamin D levels and liver enzymes in a nationally representative sample of Iranian adolescents: the childhood and adolescence surveillance and prevention of adult noncommunicable disease study. Int J Prev Med. 2018;9:24.

Wu L, He Y, Jiang B, Liu M, Yang S, Wang Y, et al. Gender difference in the association between aminotransferase levels and hypertension in a Chinese elderly population. Medicine. 2017;96:21e6996.

Stranges S, Trevisan M, Dorn JM, Dmochowski J, Donahue RP. Body fat distribution, liver enzymes, and risk of hypertension: evidence from the western New York Study. Hypertension. 2005;46:1186–93.

Ren J, Sun J, Ning F, Pang Z, Qie L, Qiao Q. Qingdao Diabetes Survey Group Gender differences in the association of hypertension with gamma-glutamyltransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels in Chinese adults in Qingdao. China J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9:951–8.

Patidar OM, Bhargava AJ, Gupta D. Association of C-reactive protein and arterial hypertension. Int J Adv Med. 2015;2:133–7.

Zangana SN. The relation of serum high-sensitive C-reactive protein to serum lipid profile, vitamin D and other variables in a group of hypertensive patients in Erbil-Iraq. Int J Sci Res. 2016;5:444–8.

Junqueira CLC, Magalhães MEC, Brandão AA, Ferreira E, Cyrino FZGA, Maranhão PA, et al. Microcirculation and biomarkers in patients with resistant or mild-to-moderate hypertension: a cross-sectional study. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:515–23.

Wannamethee SG, Lowe GD, Whincup PH, Rumley A, Walker M, Lennon L. Physical activity and hemostatic and inflammatory variables in elderly men. Circulation. 2002;105:1785–90.

Dar MS, Pandith AA, Sameer AS, Sultan M, Yousuf A, Mudassar S. hs-CRP a potential marker for hypertension in Kashmiri population. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2010;25:208–12.

Carlson N, Mah R, Aburto M, Peters MJ, Dupper MV, Chen LH, et al. Hypovitaminosis D correction and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in hypertensive adults. Perm J. 2013;17:19–21. Fall;

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr G. S Rao, Managing Director of the Yashoda group of hospitals and Dr A. Lingaiah, Director of Medical Services for their generous support in carrying out this study in Yashoda Hospital, Hyderabad.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuchulakanti, P.K., Chaudhuri, J.R., Annad, U. et al. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with primary hypertension: a study from south India. Hypertens Res 43, 389–395 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0394-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0394-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and hypertension among adults in North Sudan: a community-based cross-sectional study

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2023)

-

Recent Advances in Association Between Vitamin D Levels and Cardiovascular Disorders

Current Hypertension Reports (2023)

-

Evidence of a casual relationship between vitamin D deficiency and hypertension: a family-based study

Hypertension Research (2022)