Abstract

Hypertension is common in black populations and is known to be associated with low nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability. We compared plasma and urinary NO-related markers and plasma creatine kinase (CK) levels between young healthy black and white adults along with the associations of these markers with the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR), which is a surrogate marker of endothelial and kidney function. We included 1105 participants (20–30 years). We measured the uACR, plasma CK, plasma and urinary arginine, homoarginine, asymmetric (ADMA) and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA), urinary ornithine/citrulline, nitrate and nitrite, and malondialdehyde (MDA). In addition, the urinary nitrate-to-nitrite ratio (UNOxR) was calculated and used as a measure of circulating NO bioavailability. The uACR was comparable between the groups, yet the black group had lower urinary nitrate (by −15%) and UNOxR values (by −18%) (both p ≤ 0.001), higher plasma (by +9.6%) and urinary (by +5.9%) arginine (both p ≤ 0.004), higher plasma (by +13%) and urinary (by +3.7%) ADMA (both p ≤ 0.033), and higher CK (by +9.5%) and MDA (by +19%) (both p < 0.001) compared with white adults. Plasma and urinary homoarginine were similar between the groups. In the multiple regression analysis, we confirmed the inverse associations of the uACR with both plasma (adj. R2 = 0.066; β = −0.209; p = 0.005) and urinary (adj. R2 = 0.066; β = −0.149; p = 0.010) homoarginine and with the UNOxR (adj. R2 = 0.060; β = −0.122; p = 0.031) in the black group only. The overall less favorable NO profile and higher CK and MDA levels in the black cohort along with the adverse associations with the uACR may reflect the vulnerability of this cohort to the early development of hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increased blood pressure is a main contributing factor to cardiovascular outcomes [1], yet the origins of the early phases of disease development remain unclear. Noticeably, a cardiovascular risk factor such as hypertension—which is common in black populations [2]—may be partly due to underlying endothelial dysfunction [3, 4]. Endothelial dysfunction is measured by several noninvasive methods, including flow-mediated dilation, which has been widely used in the last few decades [5, 6]. However, more recently, the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR) has been introduced as a surrogate marker of both vascular endothelial and renal function [7,8,9]. Moreover, an elevated uACR has also been recognized to predict hypertension [10] and mortality [11] in the general population.

One of the important mediators of endothelial function is nitric oxide (NO). NO is synthesized from L-arginine (Arg) and L-homoarginine (hArg), which serve as substrates in a reaction catalyzed by NO synthase (NOS) [12]. Alternatively, NO can be formed via the reduction of the inorganic anions nitrate and nitrite, which are the main metabolites of NO [13]. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) are inhibitors of NOS activity and Arg transport [14]. Impairment of the synthesis or bioavailability of NO results in a proconstrictive phenotype [15] and has been reported to be more common in black populations [16] and hypertensive patients [10]. hArg is synthesized by L-Arg:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT) [17], an enzyme that is also responsible for the synthesis of the energy-related metabolite creatine [18]. Creatine is the substrate of creatine kinase (CK), and its synthesis requires larger quantities of available L-Arg than NO synthesis [18, 19]. This may suggest that the CK system may be sensitive to a reduction in Arg bioavailability. NO synthesis from Arg is therefore regulated not only by Arg availability but also by competition for substrates between NO and creatine synthesis.

Studies comparing the uACR and CK levels in black and white populations have provided consistent findings of increased uACR [20,21,22] and CK levels [23, 24] in black populations. However, reports on NO profiles in black and white populations have been inconsistent [20, 25, 26]. One study reported a greater NO synthesis capacity in a black population with higher levels of Arg [20], while another study observed reduced NO production and lower levels of Arg in black men [25]. In addition, a study presenting the first evaluation of the urinary nitrate-to-nitrite ratio (UNOxR) suggested that the UNOxR was a better measure of carbonic acid anhydrase-dependent nitrite reabsorption and reported a lower UNOxR in black boys compared with that in age-matched white boys, potentially suggesting an association of reduced NO synthesis with black ethnicity [27]. There have also been inconsistent findings for the endogenous NOS inhibitor ADMA, which is considered a marker of endothelial dysfunction in adults [14, 28]. Circulating ADMA was found to be lower in black populations [20, 29], higher in black Africans [26] or similar [25] when compared with that in white individuals. ADMA and SDMA are produced by the catalytic dimethylation by protein-Arg methyltransferase (PRMT) of proteinic Arg residues. ADMA and SDMA circulate in the blood and are excreted in the urine, and ADMA is also metabolized by dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) [30].

Due to the varying findings for the NO profile in black and white populations, a deeper look into NO profiles among these populations is warranted. Furthermore, no prior studies have examined both the plasma and urinary NO profiles of young and apparently healthy individuals in bi-ethnic populations. Thus, in young black and white adults, we compared NO-related markers derived from urine and plasma along with the respective plasma CK levels and determined their relationship with the uACR as a measure of endothelial and kidney function.

Methodology

The African Prospective Study on the Early Detection and Identification of Cardiovascular Disease and Hypertension (African-PREDICT) screened and assessed 1202 apparently healthy volunteers (aged 20–30 years). In this cross-sectional study, we included data from 1105 participants who were stratified according ethnicity, i.e., black (n = 539) and white (n = 566) men and women, after the exclusion of participants with nitrite outliers and those with missing NO-related and uACR data (n = 97).

The population and the protocol for the African-PREDICT study have been described elsewhere [31]. Briefly, participants with an office blood pressure >140/90 mmHg during screening or with any self-reported diseases or risk factors that may influence cardiovascular health, an internal ear temperature >37.5 °C, human immunodeficiency virus, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, cancer, tuberculosis or renal disease, as well as the use of chronic medication were excluded from the African-PREDICT study. Pregnant and lactating women were also excluded due to the known influences of hormones on cardiovascular health.

Participants were fully informed about the objectives of the study, and written informed consent was acquired from each participant. The African-PREDICT study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [32] and was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of North-West University.

Anthropometric measures

All anthropometric procedures were performed according to specific guidelines set out by the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry [31, 33]. The waist circumference (cm) was obtained using a standard protocol (Lufkin Steel Anthropometric Tape; W606PM; Lufkin; Apex; USA). The body mass index (BMI) (weight (kg)/square height (m2)) (SECA portable 213 stadiometer; SECA 813 electronic scale; Hamburg, Germany) and waist-to-hip ratio (waist circumference (cm)/hip circumference (cm)) of each participant were then calculated.

Cardiovascular measures

With a Dinamap® ProCare 100 Vital Signs Monitor, the office blood pressure was measured in the left arm and then in the right arm in duplicate, which was followed by a repeated measurement in the left upper arm (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, USA). In this study, the mean left blood pressure measurement was used in the analyses. The systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure were determined from each measurement. With a SphygmoCor XCEL device (AtCor Medical Pty. Ltd, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia), supine central systolic blood pressure readings were derived using pulse wave analysis [34].

Biochemical analyses

Participants were required to fast for at least 8 h before they provided an early morning spot urine sample. Blood samples were obtained by a registered research nurse at the Hypertension Clinic of North-West University.

Basic serum analyses included lipids (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides), gamma-glutamyl transferase, creatinine, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (Cobas Integra 400 plus Roche, Basel Switzerland). Serum cotinine levels were determined with a chemiluminescence method with an Immulite system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). CK was determined with the electrochemiluminescence method by using an E411 (Roche, Basel Switzerland). Sodium fluoride plasma glucose (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and EDTA whole blood glycated hemoglobin were also determined (Cobas Integra 400 plus Roche, Basel Switzerland). The intra-assay variability and interassay variability of all variables were below 10%. Urinary albumin (mg/L) and creatinine (mmol/L) were determined (Cobras Integra® 400 plus, Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and the uACR was calculated. Furthermore, the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology formula was utilized to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from the serum creatinine values [35].

The plasma NO-related markers (Arg, hArg, ADMA, and SDMA) of the first 561 participants were quantified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry [36, 37]. Urinary NO-related markers (Arg, hArg, ADMA, SDMA, ornithine/citrulline, nitrite, and nitrate) as well as malondialdehyde (MDA), which is a biomarker of oxidative stress, and creatinine were measured simultaneously by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry [38]. All urinary NO-related data were normalized based on creatinine excretion and are expressed as µM analyte to mM creatinine (µM/mM). The UNOxR values were calculated by dividing the urinary nitrate concentration by the urinary nitrite concentration [27].

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analyses, IBM®, SPSS® version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) was used. We tested the interactions of ethnicity with the association with the uACR with both plasma and urinary NO-related markers. Variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and QQ plots. Non-Gaussian variables were log10-transformed. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation if they were normally distributed and as the geometric mean with the 5th and 95th percentile boundaries for log10-transformed variables.

For comparisons between ethnic groups, independent T-tests were used. The proportions were determined with cross-tabs, with significant differences indicated by Chi-square tests and presented as numbers and percentages. The correlations of the uACR with plasma and urinary NO-related markers were tested using Pearson correlations. Standard multiple regression analyses were conducted with the uACR as a dependent variable, which was tested separately for its association with plasma and urinary NO-related markers. The covariates included in the multiple regression models included age, sex, waist-to-hip ratio, total cholesterol, eGFR, office systolic blood pressure, MDA, smoking, glycated hemoglobin, and CK levels.

Results

The general characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The black group had lower values for body composition measures, such as waist circumference, body height, and BMI (all p ≤ 0.002), than the white group, while body weight was comparable between the groups (p = 0.36). Diastolic blood pressure, central systolic blood pressure, and the MDA and CK levels were higher in the black group (all p ≤ 0.001) than in the white group. In addition, the mean uACR was similar (p = 0.34) between the groups.

When comparing NO-related markers (Table 2), the black group presented with lower urinary nitrate (by −15%) and UNOxR values (by −18%) (both p ≤ 0.001) and higher plasma (by +13%) and urinary (by +3.7%) ADMA values (both p ≤ 0.033). However, both the plasma (by −5.2%) and urinary (by −4.1%) SDMA values (both p ≤ 0.022) were lower in the black group than in the white group. No differences were observed for plasma and urinary hArg (both p ≥ 0.81). An interaction of ethnicity with the associations of the uACR with both plasma (all p ≤ 0.002) and urinary (all p ≤ 0.001) NO-related markers was observed (Supplementary Table 1).

We performed single regression analyses (Supplementary Table 2) that showed that the uACR was associated inversely with the plasma (r = −0.176; p = 0.006) and urinary (r = −0.100; p = 0.049) hArg and UNOxR (r = −0.169; p = 0.001) values in the black group. In addition, the uACR was positively associated with urinary nitrate (r = 0.139; p = 0.008) in the white group.

In the partial regression analyses (Supplementary Table 3) (adjusted for age, sex, and BMI), we found inverse correlations of the uACR with the plasma hArg (r = −0.178; p = 0.006) and urinary hArg (r = −0.139; p = 0.007) and UNOxR (r = −0.172; p = 0.001) values in the black group only. uACR was positively associated with urinary nitrate in the white group (r = 0.124, p = 0.018). Noticeably, CK levels were inversely associated with urinary hArg (r = −0.413; p = 0.012) in the black group only. The oxidative stress biomarker MDA was inversely associated with the UNOxR in the black (r = −0.319; p < 0.001) and white groups (r = −0.204; p < 0.001).

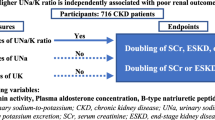

In the multivariable-adjusted regression analysis (Fig. 1), we observed consistent inverse associations between the uACR and both plasma (adj. R2 = 0.066; β = −0.209; p = 0.005) and urinary (adj. R2 = 0.066; β = −0.149; p = 0.010) hArg as well as between the uACR and the UNOxR (adj. R2 = 0.060; β = −0.122; p = 0.031).

Discussion

In the present exploratory study involving a healthy cohort of both black and white patients, we compared plasma and urinary NO-related markers along with the CK levels and determined the associations with the uACR, which is an early marker of endothelial dysfunction [39]. The NO-related markers included the NOS substrates Arg and hArg [12, 17], the NOS inhibitors ADMA and SDMA [14, 40], urinary nitrate, which is a major NO metabolite reflecting whole-body NO synthesis [41], and urinary nitrite, which is a measure of the loss of circulating NO bioactivity [27]. We also measured urinary MDA, which is a measure of kidney-related oxidative stress [42]. We observed an overall less favorable NO profile and elevated oxidative stress in the black cohort. Although the uACR did not differ between the black and white groups, the uACR was found to be independently and inversely associated with the UNOxR, plasma hArg and urinary hArg in the black cohort only. In addition, the plasma CK levels were inversely associated with urinary hArg in the black group only.

The results of our study are in line with those of a previous bi-ethnic study on black and white children, which found that black boys presented lower (by −35%) UNOxR levels than white boys [27]. The reduced urinary nitrate and UNOxR (by −18%) levels in the young black adults in the present study illustrate that whole-body NO synthesis is reduced in black individuals, with the difference between black and white individuals appearing to decrease with age. This may be attributable to genetic differences in the enzymes involved in the Arg/NO pathway, including NOS, AGAT, PRMT, and DDAH, as well as in the renal carbonic anhydrases (CA) and anion transporters involved in nitrite excretion and reabsorption from the primary urine, as previously reported [27, 43]. In addition to reduced urinary nitrate and UNOxR values, the black group also displayed increased plasma and urinary levels of Arg and ADMA, which are an endogenous NOS substrate and inhibitor, respectively. Studies have reported increased Arg [20, 44] and ADMA levels [26] in black adults; however, other studies have reported findings of both increased Arg levels and increased ADMA levels in the same study population [28, 45]. The metabolic fate of Arg is complex and involves the arginase-catalyzed hydrolysis of Arg to generate ornithine, thus potentially decreasing Arg concentrations and local NO synthesis [46]. Animal studies have suggested that the expression of arginase may be elevated in hypertensive rats [47, 48]. However, the bi-ethnic differences in the Arg and ornithine/citrulline concentrations observed in our study were relatively small, especially with respect to the differences in whole-body NO synthesis. Therefore, differences in arginase expression and activity are probably unlikely to have affected NO synthesis from Arg in our study. The ethnic disparities in regard to the NO profile of our bi-ethnic cohort seem to be multifactorial and include genetic and environmental factors, which, however, are unknown. Since decreased NO synthesis is associated with hypertension [49], the decrease in NO synthesis found in the black group in this study could be responsible for the increased susceptibility of the population to the development of hypertension later in life.

In the first instance, the uACR is an indicator of kidney function, primarily that of the glomerulus [8]. However, the uACR is also generally accepted to be an indicator of cardiovascular disease [9] and early endothelial dysfunction [39]. In our study, we found inverse associations of the uACR with the UNOxR and hArg (both in plasma and in urine) in the black group only, although both groups presented with relatively similar UNOxR values. Such associations have not been previously described in a black population and may suggest the considerable contribution of the kidney to these ethnic differences. Indeed, the black group presented with higher (by +10%) eGFR values compared with the white group of the cohort. The decreased UNOxR values measured in the black young adults in this study may indicate a relative increase in the loss of circulating nitrite, which is an important reservoir of NO bioactivity, due to attenuated CA activity in the proximal tubule of the nephron. Interestingly, the attenuation of renal CA activity is more pronounced in childhood [27] than in adulthood in black individuals.

The inverse association of plasma CK with urinary hArg (r = −0.413; p = 0.012) but not with plasma hArg in the black group only may suggest the considerable contribution of kidney function to this association. By comparing the (h)Arg level with the ADMA plasma and SDMA urine concentrations, the urinary hArg content was found to be relatively low (Table 2). This suggests the occurrence of considerable tubular reabsorption of hArg. CK expressed in tubular cells of the kidney provides the ATP necessary for Na+/K+-ATPase activity, which drives several tubular transport mechanisms, including Na+ reabsorption in Henle’s loop and the distal tubule [50, 51]. In a small cohort of African and European young men, plasma CK was found to be inversely associated with Na+ excretion [51]. Increased CK activity has been observed in people from the sub-Saharan African region and has been discussed as a factor contributing to hypertension in individuals of this ethnicity [23, 24].

Our large study confirms the increased (by +10%) CK levels in black individuals. The increased urinary MDA excretion rate (by +19%) measured in the black group may be an indication that the kidneys of the young black adults of this study may have also been subjected to higher oxidative stress than the kidneys of their white counterparts. Elevated oxidative stress may in itself reduce NO bioavailability by increasing NO inactivation, as seen in Africans [52] and Europeans [53]. Not only does an increase in oxidative stress damage the endothelium by impairing endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation (diminished NO), it also increases vascular contractile activity, which may result in hypertension [54]. These findings further reiterate that an increase in oxidative stress (MDA) [20], combined with decreased renal and systemic nitrite levels, may reduce NO bioavailability in the black population, which may contribute to structural changes in blood vessels and ultimately result in the early onset of hypertension.

The inverse association of plasma CK with urinary hArg may indicate that there is a mutual interaction between CK and AGAT in the mitochondria and cytoplasm of kidney cells. This is expected because AGAT not only produces hArg but also guanidino acetic acid (GAA). GAA is further converted to creatine, which, in turn, is the substrate of CK and an inhibitor of the AGAT-catalyzed synthesis of hArg and GAA [17, 55]. Notably, hArg has been shown to be associated with many human diseases. In particular, low circulating and excretory levels of hArg are associated with all-cause mortality [17, 56]. However, the biological activities of hArg remain almost entirely unknown. The kidney has been reported to be a major contributor to circulating and urinary hArg [57,58,59], underlining the major importance of renal AGAT activity in humans. In the present study, we did not find differences in the plasma and urinary hArg levels between black and white young adults. In the healthy young adults in this study, both plasma and urinary hArg levels were closely comparable to those reported for healthy humans [56]. However, the disparate associations of urinary hArg with CK and the uACR indicate the occurrence of ethnic differences in these biomarkers, which presumably are related to kidney physiology.

This explorative study must be interpreted within the context of its strengths and limitations. The study was well planned and executed under strict conditions. As our population included participants from the North-West Province of South Africa, it is not representative of the population as a whole. The study is limited by its cross-sectional design; hence, we were unable to investigate the precise mechanisms and causal relationships. The participants in our study did not observe strict abstinence from a nitrate-rich diet. Dietary nitrate may have contributed to some degree to urinary nitrate but not to other biomarkers, including ADMA and hArg. Forthcoming studies on the potential involvement of Arg/NO and related pathways need to include a nitrate-poor dietary protocol.

To conclude, young black asymptomatic adults partially differ from their white counterparts with respect to various biomarkers and some of the associations between these biomarkers. Reduced urinary nitrate excretion indicates decreased whole-body NO synthesis, and a reduced UNOxR indicates renal CA-dependent loss of circulating nitrite, which is a major reservoir of NO; increased plasma ADMA levels are indicative of the elevated inhibition of NOS activity. These occurrences and the inverse associations, notably those with the uACR, which is a biomarker of early endothelial dysfunction, plasma CK, urinary MDA, which is a biomarker of kidney-associated oxidative stress, and urinary hArg, which is an endogenous substance with largely unknown biological activities, were observed only in the black cohort in the study, suggesting that there were ethnicity-dependent differences in several overlapping Arg-involving pathways, i.e., pathways involving Arg/NO, AGAT, arginase, CK, and oxidative stress. Our study suggests that these differences originate in the cardiovascular and renal systems. Young black individuals seem to show increased susceptibility to the development of premature hypertension later in life.

References

Fuchs FD, Whelton PK. High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2020;75:285–92.

Opie HL, Seedat YK. Hypertension in sub-Saharan African populations. Circulation. 2005;112:3562–8.

Sander M, Chavoshan B, Victor RG. A large blood pressure-raising effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibition in humans. Hypertension. 1999;33:937–42.

Verma S, Buchanan MR, Anderson TJ. Endothelial function testing as a biomarker of vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;108:2054–9.

Anderson TJ. Prognostic significance of brachial flow-mediated vasodilation. Circulation. 2007;115:2373–5.

Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Miller OI, Sullivan I, et al. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1992;340:1111–5.

Malik A, Sultan S, Turner S, Kullo IJ. Urinary albumin excretion is associated with impaired flow- and nitroglycerin-mediated brachial artery dilatation in hypertensive adults. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:231–8.

Glassock RJ. Is the presence of microalbuminuria a relevant marker of kidney disease? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:364–8.

Abdelhafiz AH, Ahmed S, El Nahas M. Microalbuminuria: marker or maker of cardiovascular disease. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2011;119 Suppl 1:e6–10.

Jessani S, Levey AS, Chaturvedi N, Jafar TH. High normal levels of albuminuria and risk of hypertension in Indo-Asian population. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2011;10:1093.

Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2073–81.

Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharm Rev. 1991;43:109–42.

Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Disco. 2008;7:156–67.

Böger RH. Association of asymmetric dimethylarginine and endothelial dysfunction. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:1467–72.

Moncada S, Higgs A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:2002–12.

Ozkor MA, Rahman AM, Murrow JR, Kavtaradze N, Lin J, Manatunga A, et al. Differences in vascular nitric oxide and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor bioavailability in blacks and whites. Arterioscl, Thromb, Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1320–7.

Choe CU, Atzler D, Wild PS, Carter AM, Böger RH, Ojeda F, et al. Homoarginine levels are regulated by L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase and affect stroke outcome: results from human and murine studies. Circulation. 2013;128:1451–61.

Karamat FA, van Montfrans GA, Brewster LM. Creatine synthesis demands the majority of the bioavailable L-arginine. J Hyp. 2015;13:2368.

Handy D, Sclaro J, Chen J, Helang P, Loscalzo J. L-arginine increases plasma homocysteine in apoe-/-/inos-/-double knock out mice. Cell Mol Biol. 2004;50:903–9.

Mels CMC, Huisman HW, Smith W, Schutte R, Schwedhelm E, Atzler D, et al. The relationship of nitric oxide synthesis capacity, oxidative stress, and albumin-to-creatinine ratio in black and white men: the SABPA Study. Age. 2016;38:9.

Schutte R, Schmieder RE, Huisman HW, Smith W, van Rooyen JM, Fourie CM, et al. Urinary albumin excretion from spot urine sample predict all-cause and stroke mortality in Africans. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:811–8.

Phalane E, Fourie CMT, Schutte AE. The metabolic syndrome and renal function in an African cohort infected with human immunodeficiency virus. SA J HIV Med. 2018;19:1–10.

Brewster LM, Coronel CM, Sluiter W, Clark JF, Van Montfrans GA. Ethnic differences in tissue creatine kinase activity: an observational study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32471.

Brewster LM, Clark JF, van Montfrans GA. Is greater tissue activity of creatine kinase the genetic factor increasing hypertension risk in black people of sub-Saharan African descent? J Hypertens. 2000;18:1537–44.

Glyn MC, Anderssohn M, Luneberg N, Van Rooyen JM, Schutte R, Huisman HW, et al. Ethnic-specific differences in L-arginine status in South African men. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26:737–43.

Melikian N, Wheatcroft SB, Ogah OS, Murphy C, Chowienczyk PJ, Wierzbicki AS, et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and reduced nitric oxide bioavailability in young Black African men. Hypertension. 2007;49:873–7.

Tsikas D, Hanff E, Bollenbach A, Kruger R, Phan VV, Chobanyan-Jurgens K, et al. Results, meta-analysis and a first evaluation of UNOxR, the urinary nitrate-to-nitrite molar ratio, as a measure of nitrite reabsorption in experimental and clinical settings. Amino Acids. 2018;50:799–821.

Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Maio R, Perticone M, Maas R, Böger RH, et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine, L-arginine and endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:518–23.

Sydow K, Fortmann SP, Fair JM, Varady A, Hlatky MA, Go AS, et al. Distribution of asymmetric dimethylarginine among 980 healthy, older adults of different ethnicities. Clin Chem. 2010;56:111–20.

Leiper JM. The DDAH-ADMA-NOS pathway. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27:744–6.

Schutte AE, Gona PN, Delles C, Uys AS, Burger A, Mels CMC, et al. The African prospective study on the early detection and identification of cardiovascular disease and hypertension (African-PREDICT): design, recruitment and initial examination. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26:458–70.

Carlson RV, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharm. 2004;57:659–713.

Stewart A, Marfell-Jones M. International standards for anthropometric assessment. Lower Hutt, New Zealand: International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry; 2011.

Pauca AL, O’Rourke MF, Kon ND. Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension. 2001;38:932–7.

Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HL, Greene T, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Eng. J Med. 2012;367:20–29.

Schwedhelm E, Tan-Andresen J, Maas R, Riederer U, Schulze F, Boger RH. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for the analysis of asymmetric dimethylarginine in human plasma. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1268–71.

Atzler D, Mieth M, Maas R, Böger RH, Schwedhelm E. Stable isotope dilution assay for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric determination of L-homoarginine in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879:2294–8.

Hanff E, Lützow M, Kayacelebi AA, Finkel A, Maassen M, Yanchev GR, et al. Simultaneous GC-ECNICI-MS measurement of nitrite, nitrate and creatinine in human urine and plasma in clinical settings. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2017;2017:207–14.

Bartz SK, Caldas MC, Tomsa A, Krishnamurthy R, Bacha F. Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio: a marker of early endothelial dysfunction in youth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:3393–9.

Tsikas D, Sandmann J, Savva A, Luessen P, Böger RH, Gutzki FM, et al. Assessment of nitric oxide synthase activity in vitro and in vivo by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2000;742:143–53.

Tsikas D. Circulating and excretory nitrite and nitrate: their value as measures of nitric oxide synthesis, bioavailability and activity is inherently limited. Nitric Oxide. 2015;45:1–3.

Tsikas D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: analytical and biological challenges. Anal Biochem. 2017;524:13–30.

Schneider JY, Rothmann S, Schröder F, Langen J, Lücke T, Mariotti F, et al. Effects of chronic oral l-arginine administration on the L-arginine/NO pathway in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease or coronary artery disease: L-Arginine prevents renal loss of nitrite, the major NO reservoir. Amino Acids. 2015;47:1961–74.

Reimann M, Hammer M, Malan NT, Schlaich MP, Lambert GW, Ziemssen T, et al. Effects of acute and chronic stress on the L-arginine nitric oxide pathway in black and white South Africans: the sympathetic activity and ambulatory blood pressure in Africans study. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:751–8.

Moss MB, Brunini TM, Soares De Moura R, Novaes Malagris LE, Roberts NB, Ellory JC, et al. Diminished L-arginine bioavailability in hypertension. Clin Sci. 2004;107:391–7.

Morris CR, Poljakovic M, Lavrisha L, Machado L, Kuypers FA, Morris SM Jr. Decreased arginine bioavailability and increased serum arginase activity in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:148–53.

Iwata S, Tsujino T, Ikeda Y, Ishida T, Ueyama T, Gotoh T, et al. Decreased expression of arginase II in the kidneys of Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertens Res. 2002;25:411–8.

Rodriguez S, Richert L, Berthelot A. Increased arginase activity in aorta of mineralocorticoid-salt hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2000;22:75–85.

Hermann M, Flammer A, Lüscher TF. Nitric oxide in hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2006;8 12 Suppl 4:17–29.

Bastin J, Cambon N, Thompson M, Lowry OH, Burch HB. Change in energy reserves in different segments of the nephron during brief ischemia. Kidney Int. 1987;31:1239–47.

Brewster LM, Oudman I, Nannan Panday RV, Khoyska I, Haan YC, et al. Creatine kinase and renal sodium excretion in African and European men on a high sodium diet. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20:334–41.

Yale BM, Yeldu MH. Serum Nitric Oxide and Malondialdehyde in a hypertensive population in Sokoto, Nigeria. Int. J Res Med Sci. 2018;6:3929–34.

Modun D, Krnic M, Vukovic J, Kokic V, Kukoc-Modun L, Tsikas D, et al. Plasma nitrite concentration decreases after hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress in healthy humans. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012;32:404–8.

Intengan HD. Structure and mechanical properties of resistance arteries in hypertension: tole of adhesion molecules and extracellular matrix determinants. Hypertension. 2000;36:312–8.

Edison EE, Brosnan ME, Meyer C, Brosnan JT. Creatine synthesis: production of guanidinoacetate by the rat and human kidney in vivo. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2007;293:F1799–804.

Zinellu A, Paliogiannis P, Carru C, Mangoni AA. Homoarginine and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48:e12960.

Frenay AR, Kayacelebi AA, Beckmann B, Soedamah-Muhtu SS, de Borst MH, van den Berg E, et al. High urinary homoarginine excretion is associated with low rates of all-cause mortality and graft failure in renal transplant recipients. Amino Acids. 2015;47:1827–36.

Kayacelebi AA, Minović I, Hanff E, Frenay AS, de Borst MH, Feelisch M, et al. Low plasma homoarginine concentration is associated with high rates of all-cause mortality in renal transplant recipients. Amino Acids. 2017;49:1193–202.

Hanff E, Said MY, Kayacelebi AA, Post A, Minovic I, van den Berg E, et al. High plasma guanidinoacetate-to-homoarginine ratio is associated with high all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rate in adult renal transplant recipients. Amino Acids. 2019;51:1485–99.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all individuals who participated voluntarily in the African-PREDICT study. The dedication of the support and research staff as well as the students at the Hypertension Research and Training Clinic at the North-West University (Potchefstroom campus) are also duly acknowledged.

Funding

The research funded in this manuscript is part of an ongoing research project financially supported by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) with funds from the National Treasury under the Economic Competitiveness and Support Package; the South African Research Chairs Initiative (SARChI) of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa (GUN 86895); SAMRC with funds received from the South African National Department of Health, GlaxoSmithKline R&D (Africa Non-Communicable Disease Open Lab grant), the UK Medical Research Council with funds from the UK Government’s Newton Fund; and corporate social investment grants from Pfizer (South Africa), Boehringer-Ingelheim (South Africa), Novartis (South Africa), the Medi Clinic Hospital (South Africa), and kind contributions from the Roche Group (South Africa). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors, and therefore, the NRF does not accept any liability in this regard.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Craig, A., Mels, C.M.C., Schutte, A.E. et al. Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio is inversely related to nitric oxide synthesis in young black adults: the African-PREDICT study. Hypertens Res 44, 71–79 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0514-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0514-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The relationship between kidney function and the soluble (pro)renin receptor in young adults: the African-PREDICT study

BMC Nephrology (2025)

-

Hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: the current profile, recent advances, gaps, and priorities

Journal of Human Hypertension (2024)

-

Love is in the hair: arginine methylation of human hair proteins as novel cardiovascular biomarkers

Amino Acids (2022)