Abstract

The present prospective observational study was conducted to examine the differences in longitudinal associations of the conventional risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) with arterial stiffness and with abnormal pressure wave reflection using repeated measurement data. In 4016 healthy middle-aged (43 ± 9 years) Japanese men without CVD at baseline, the conventional risk factors for CVD, brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (brachial–ankle PWV) and radial augmentation index (rAI) were measured annually over a 9-year period. Mixed-model linear regression analysis demonstrated a significant independent positive longitudinal association of the mean blood pressure with both the brachial–ankle PWV (estimate = 5.51, standard error = 0.30, P < 0.01) and the rAI (estimate = 0.19, standard error = 0.02, P < 0.01). On the other hand, the serum levels of glycohemoglobin, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides showed longitudinal associations only with the brachial–ankle PWV and not the rAI. In addition, while the radial AI was found to show a significant longitudinal association with the brachial–ankle PWV, the inverse association was not significant. In conclusion, the conventional risk factors for CVD showed heterogeneous longitudinal associations with arterial stiffness and/or abnormal pressure wave reflection. Elevated blood pressure showed independent longitudinal associations with both arterial stiffness (macrovascular damage) and abnormal pressure wave reflection, suggesting that BP is also longitudinally associated, at least in part, with microvascular damage. On the other hand, abnormal glucose metabolism and dyslipidemia showed independent longitudinal associations with only arterial stiffness (macrovascular damage).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increased arterial stiffness and abnormal pressure wave reflection are well known as independent risk factors for the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1,2,3]. While an interaction is known to exist between arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection as risk factors for the development of CVD [4,5,6,7], the mechanisms by which arterial stiffness and abnormal pressure wave reflection serve as risk factors for the development of CVD are thought to differ, at least in part [4,5,6,7]. The structure and function of the circulatory system are determined by both the macrovasculature and the microvasculature [8]. Abnormal pressure wave reflection is thought to be associated with both arterial stiffness (i.e., macrovascular damage), which increases the propagation speed of the reflected pressure wave along the arterial wall, and peripheral vascular damage (i.e., microvascular damage), which increases the pressure wave reflectance [6, 9]. It is also known that microvascular damage is associated with augmentation of the pressure wave reflection, independent of macrovascular damage [10]. Therefore, abnormal pressure wave reflection without an accompanying increase in arterial stiffness may reflect, at least in part, isolated microvascular damage [10].

The clarification of the individual associations of the conventional risk factors for CVD with arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection is crucial for the management of CVD-related pathophysiological abnormalities. Because longitudinal fluctuations are known conventional risk factors [11, 12], cross-sectional analyses are not sufficient to clarify the individual associations of conventional risk factors with arterial stiffness/pressure wave reflection. However, studies have scarcely been conducted to examine longitudinal associations and take into account the time-varying effects of conventional risk factors.

Recently, mixed-model linear regression analysis (MML) of repeated measures data has been proposed as a valid analytical tool to exclude the confounding effects of time-varying variables [13]. Therefore, we conducted this study to examine the differences in the longitudinal associations of the conventional risk factors for CVD with arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection using repeated measurement data of the conventional risk factors for CVD, arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection obtained over a 9-year period in the employees of a single large Japanese construction company [5, 14, 15].

Methods

The present study was conducted in the same cohort as that used in a previously reported prospective observational study [5, 14, 15]. The cohort consisted of employees working at the headquarters of a single large Japanese construction company located in downtown Tokyo. According to the Occupational Health and Safety Law in Japan, it is mandatory for all company employees to undergo annual health check-ups. Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from each of the study participants prior to their enrolment in this study. The study was conducted with the approval of the Ethical Guidelines Committee of Tokyo Medical University (Nos. 209 and 210 in 2003).

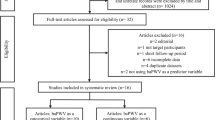

The health check-up data obtained for the years 2007–2015 were used for the present study. Of the 5857 employees at the headquarters of the construction company who had undergone measurement of the brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (brachial–ankle PWV), a marker of arterial stiffness, at least once, 834 who underwent the measurement only once during the study period (most of these were temporary employees), 334 subjects with unreliable accuracy of the measured brachial–ankle PWV and 673 women were excluded. Finally, the data of the remaining 4016 men were included in our analyses. The subject selection flow diagram is summarised in Fig. 1.

Measurements

The details of the measurements have already been reported elsewhere. Brachial systolic/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) was recorded as the mean of two measurements obtained in an office setting by the conventional cuff method using a mercury sphygmomanometer. Some studies have reported that mean blood pressure (MBP), a steady component of blood pressure, is an important determinant of PWV [16,17,18]. Pulse pressure (PP) is calculated as the SBP—DBP, and MBP is calculated as DBP + PP/3.

The radial augmentation index (radial AI), a marker of pressure wave reflection, was measured using an arterial applanation tonometry probe equipped with an array of 40 micropiezo-resistive transducers (HEM-9010AI; Omron Healthcare Co., Ltd), with the subject in a seated position [19]. The brachial–ankle PWV was measured using a volume–plethysmographic apparatus (Form/ABI, Omron Healthcare Co., Ltd, Kyoto, Japan), with the subject in a supine position [20]. Serum concentrations of uric acid (UA), triglycerides (TGs), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) and creatinine, as well as the plasma glucose and HbA1c concentrations, were measured using standard enzymatic methods (Beckman Coulter, Model AU5431, Falco Biosystems Co., Ltd, Tokyo). HbA1c was recorded according to the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) values. These values, which were represented according to the Japan Diabetic Society until 2011, were converted to NGSP values (i.e., JDS value + 0.4) [21]. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from serum creatinine using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation [22] for Japanese subjects.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the means ± SDs, unless otherwise indicated. The differences in the measured values between the baseline and final examinations were assessed by the paired t-test for continuous variables and by McNemar’s nonparametric test for categorical variables. The variables measured at the start of the study period were compared with the values measured annually thereafter during the study period by general linear model univariate analysis.

To determine the longitudinal associations of the explanatory variables with the brachial–ankle PWV and radial AI, MML analyses were performed. The time effect was entered as the interaction term between time (years from the baseline) and each of the explanatory variables to determine the fixed effect, and beta estimates of the interaction between time and each of the explanatory variables reflected the annual changes in each of the outcome variables per unit annual increase in the corresponding explanatory variable. The MML analyses were conducted using five different model structures (autoregressive (1), compound symmetry, diagonal, Toeplitz and unstructured). Then, Akaike’s information criterion was used to determine the best model structure. First, each explanatory variable was entered individually into the MML model to examine the crude fixed effect of each explanatory variable. Then, the significant variables in individual MML analyses were entered simultaneously with history of medication for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and/or hyperuricemia (for each of the above: not receiving medication = 0, receiving medication = 1) as a random effect in the same MML model to examine the fixed effect of each explanatory variable.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 24.0; IBM/SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). P < 0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference in all statistical tests.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the men at the start of the study and at the final observation. “End of the study period” was defined as the last examination of the participants who had undergone at least two annual examinations. The mean and median of the number of measurements were 5.2 and 5.0 (603 subjects were measured two times), respectively, and the mean and median of the follow-up period were 6.3 and 7.0 years, respectively. The radial AI, brachial–ankle PWV, BMI, serum levels of HbA1c and number of subjects prescribed medications for hypertension, dyslipidemia diabetes mellitus and/or hyperuricemia increased significantly during the study period. On the other hand, the number of current smokers; heart rate; PP; serum levels of HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, TGs and UA; and eGFR decreased significantly during the study period (Table 1). In addition, Fig. 2 shows the mean brachial–ankle PWV values, mean radial AI values and number of study subjects from the start to the end of the study period, measured annually. The brachial–ankle PWV and radial AI showed significant longitudinal increases during the study period.

Annual changes in the brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity values, radial augmentation index values and number of study subjects from the start to the end of the study period. Brachial–ankle PWV brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity, radial AI radial augmentation index, n number of study subjects, Start start of the study period, AN, e.g., 2nd AN second annual observation. * = P < 0.05 vs. start

As shown in Table 2, the MML regression analysis without adjustments revealed significant positive longitudinal associations of the radial AI; age; BMI; MBP; SBP; DBP; PP; heart rate; and serum levels of LDL cholesterol, TGs, HbA1c and UA, but not the smoking habit, and a significant negative association of the eGFR with the brachial–ankle PWV. Serum HDL cholesterol also showed a positive, rather than negative, longitudinal association with brachial–ankle PWV. Then, we prepared four MML models to examine the effects of all the measures of BP (i.e., MBP, SBP, DBP and PP) on brachial–ankle PWV. In these models, the radial AI; age; each of the BP variables (i.e., MBP, SBP, DBP and PP were individually entered); BMI; heart rate; and serum levels of LDL cholesterol, TGs, HbA1c and UA; and eGFR were entered in the same MML model as the explanatory variables, with adjustments for history of medication for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and/or hyperuricemia. These analyses identified the radial AI, age, each of the blood pressure variables (i.e., MBP, SBP, DBP and PP), heart rate, serum levels of TGs, LDL cholesterol and HbA1c, but not serum UA, as showing significant independent positive longitudinal associations with the brachial–ankle PWV (Table 2). In addition, a significant negative longitudinal association was observed between BMI and brachial–ankle PWV when MBP, SBP or DBP was entered into the model. On the other hand, a significant positive longitudinal association of the eGFR with the brachial–ankle PWV was observed when the DBP or PP was entered in the model (Table 2).

As shown in Table 3, the MML regression analysis without adjustments identified significant positive longitudinal associations of age, MBP, SBP and DBP, but not PP, and significant negative longitudinal associations of BMI and heart rate with radial AI. However, no significant longitudinal association was observed between the brachial–ankle PWV and the radial AI. In addition, the serum levels of LDL cholesterol, TGs and UA showed significant negative longitudinal associations with radial AI. Then, we prepared four MML models to examine the effect of MBP, SBP or DBP on the radial AI. In these models, age, each of the BP variables (i.e., MBP, SBP and BP were individually entered), BMI, heart rate and serum levels of LDL cholesterol, TGs and UA were entered in the same MML model as the explanatory variables, with adjustments for a history of medication for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and/or hyperuricemia. These analyses identified age and each of the BP variables (i.e., MBP, SBP and DBP) as showing a significant independent positive longitudinal association and serum levels of LDL cholesterol as showing a significant negative longitudinal association with radial AI (Table 3).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to simultaneously examine the differences among longitudinal associations of the conventional risk factors for CVD with arterial stiffness and abnormal pressure wave reflection. In our analyses of the longitudinal associations, three blood pressure variables (i.e., MBP, SBP and DBP) showed significant independent longitudinal associations with both arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection. On the other hand, the serum levels of HbA1c, LDL and TGs showed significant independent longitudinal associations with arterial stiffness but not pressure wave reflection.

Associations with blood pressure

Meta-analyses involving reanalysis of cross-sectional data have reported that blood pressure is a major factor associated with the progression of arterial stiffness [23], and a longitudinal cohort study conducted in Baltimore also reported a similar result [24]. The present study was conducted to examine the association of brachial–ankle PWV with BP variables (i.e., MBP, SBP, DBP and PP); all of these BP variables were found to show significant independent associations with brachial–ankle PWV. Thus, a longitudinal association of macrovascular damage, which is known to be related to arterial stiffness, with elevated blood pressure may exist.

On the other hand, some studies have reported inconsistent associations of blood pressure with pressure wave reflection [19, 25]. The present study demonstrated significant longitudinal associations of the three BP variables (i.e., MBP, SBP and DBP) with radial AI. On the other hand, the brachial–ankle PWV, a marker of macrovascular damage (i.e., arterial stiffness), acts to increase the amplitude of the pressure wave reflection by increasing the propagation speed of the pressure wave along the arterial wall [4, 6]. However, no significant longitudinal association of the brachial–ankle PWV with the radial AI was observed. Thus, as mentioned above, microvascular damage can also act to increase the amplitude of the pressure wave reflection, independent of macrovascular damage [10].

The summation of the forward pressure wave and reflected pressure wave (i.e., augmentation of the pressure wave reflection) is observed in the aorta, which increases the functional arterial stiffness by increasing the blood pressure in the aorta [5]. On the other hand, increased arterial stiffness augments the pressure wave reflection by increasing the propagation speed of the pressure wave along the arterial wall [4, 6]. Then, in a previous study conducted by us in subjects with normal blood pressure (i.e., without increased arterial stiffness), we observed a bidirectional longitudinal association between the brachial–ankle PWV and radial AI [5]. The reflection point is a major determinant of pressure wave reflection [4,5,6]. In the normal arterial tree, the wall elasticity is higher in proximal sites than in distal sites [5, 18]. The elastic gradient is thought to play an important role in determining the pressure wave reflection point [5, 18]. However, the present study included subjects with increased arterial stiffness. In the presence of increased arterial stiffness, arterial stiffening is more prominent in proximal than in distal sites of the arterial tree, and the forward pressure wave propagates to distal sites [26]. This distal shift of the pressure wave reflection point (i.e., impedance mismatch) attenuates the amplitude of the augmented pressure wave reflection [26], which could explain the absence of a significant longitudinal association of the brachial–ankle PWV with the radial AI.

Association with glucose metabolism and lipid metabolism

While several cross-sectional or prospective studies have reported an association of diabetes mellitus/abnormal glucose metabolism with increased arterial stiffness [25, 27, 28], the precise longitudinal associations have yet to be clarified. The present study confirmed a significant longitudinal association of abnormal glucose metabolism with increased arterial stiffness but not with augmented pressure wave reflection. This longitudinal association was significant even after the adjustment of the prevalence of anti-hypertensive medication, which acts to attenuate pressure wave reflection [4, 7]. Several studies have reported that abnormal glucose metabolism results not only in macrovascular damage but also in microvascular damage [6,7,8,9]. However, as mentioned above, in cases with macrovascular damage, the attenuation of the augmented pressure wave reflection caused by impedance mismatch may overcome the augmentation of the pressure wave reflection associated with microvascular damage. Therefore, abnormal glucose metabolism may be longitudinally associated mainly with macrovascular damage, which is known to be related to increased arterial stiffness.

Cross-sectional analyses have revealed independent associations of serum LDL cholesterol levels with both arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection [29, 30]. On the other hand, the cross-sectional analyses revealed an association of the serum TG level with arterial stiffness but not pressure wave reflection [31, 32]. In regard to the longitudinal associations, the present study revealed that both the serum LDL cholesterol level and serum TG level showed significant independent longitudinal associations with arterial stiffness but not with pressure wave reflection. Thus, dyslipidemia may longitudinally affect macrovascular damage rather than microvascular damage. Furthermore, the abovementioned impedance mismatch, which attenuates the augmentation of pressure wave reflection, could be one of the plausible explanations for the negative longitudinal association of serum LDL cholesterol, which is known to be associated with arterial stiffness, with radial AI.

Abnormal glucose metabolism and dyslipidemia increase oxidative stress and/or induce vascular inflammation, which results in vascular damage [33, 34]. Abnormal glucose/lipid metabolism impairs endothelial function via these mechanisms [7], and Badwar et al. reported that endothelial function influences arterial stiffness to a greater degree than pressure wave reflection [35]. This could be one of the plausible explanations for the association of abnormal glucose/lipid metabolism with macrovascular rather than microvascular damage in the present study.

While inconsistent findings have been reported regarding the cross-sectional association of serum HDL levels with arterial stiffness [31, 36, 37], in the present study, a significant positive longitudinal association of serum HDL levels with arterial stiffness was observed. We have no valid explanation for this unexpected observation but suggest the following as plausible explanations: (1) dissociation of the increase in the brachial–ankle PWV (significant increase) from the serum HDL cholesterol levels (very small change) and (2) during the study period, medication for dyslipidemia was initiated in 5% of study subjects, and we did not clarify the details of the medications used; drugs such as statins preferentially lower serum LDL cholesterol and TGs over the serum HDL cholesterol [38] and decrease arterial stiffness [39]. These dissociated effects of medications for dyslipidemia might affect, at least in part, the inverse longitudinal association between brachial–ankle PWV and serum HDL cholesterol.

Renal dysfunction

Several studies have reported that increased arterial stiffness is a risk factor for the progression of renal dysfunction [40]. In a previous study conducted in the same study cohort, we found that elevated brachial–ankle PWV served as a risk factor for accelerated eGFR decline [41]. However, in the present study, the radial AI did not show a significant longitudinal association with the eGFR. Furthermore, the brachial–ankle PWV showed a positive, rather than negative, longitudinal association with the eGFR. This inverse association was significant even when DBP or PP was entered in the analysis model (in the case of SBP, it was marginally significant). In addition, no significant longitudinal association of the brachial–ankle PWV with the serum creatinine level was observed in this study (estimate = −8.55, 95% confidence interval = −61.44 to 44.34, P = 0.75). Thus, compared to high blood pressure or abnormal glucose and/or lipid metabolism, the longitudinal association of renal dysfunction with arterial stiffness might be relatively weak. In addition, at the end of the study period, 15% of study subjects were treated with anti-hypertensive medication, and this medication might modulate the association of arterial stiffness with renal function, at least in part.

Clinical implications

Improvement in arterial stiffness resulting from medications for the risk factors for CVD has been reported [42]. In addition, the present study suggested that each of the conventional risk factors for CVD revealed heterogeneous associations with the progression of arterial stiffness/pressure wave reflection. Therefore, for cases with increased arterial stiffness, the management of not only hypertension but also diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia might be crucial. On the other hand, for the case of abnormal pressure wave reflection, the management of hypertension might be crucial. Further studies are needed to clarify whether such tailor-made management is necessary for achieving regression of these pathophysiological abnormalities and for preventing the risk of developing CVD.

BMI showed a negative longitudinal association with both arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection. While inconsistent results have been reported in regard to this association previously [43, 44], a plausible explanation for our present finding is that the adipose tissue encapsulating the small conduit arteries in subjects with elevated BMI may slow the pressure wave reflection and lower the systemic arterial stiffness [45]. On the other hand, Tang et al. reported that arterial stiffness, as measured by the brachial–ankle PWV, increased with BMI, although this association was no longer seen after all other cardiovascular risk factors were adjusted for in the analysis [46]. Despite the significance of the contribution of obesity to increased arterial stiffness having not been clearly concluded, other risk factors for CVD associated with obesity act to increase arterial stiffness, and therefore, the management of obesity is also an important issue.

Study limitations

The present study had some limitations, as follows: (1) in our previous study, we demonstrated an association of brachial–ankle PWV with the amount of tobacco smoked, but data on the amount of tobacco smoked were not available from 2010 for this cohort [47]; therefore, we could not examine that association; (2) in our previous study, we demonstrated an association of brachial–ankle PWV with serum UA levels in normotensive subjects [15]. High blood pressure was a major determinant of brachial–ankle PWV in the present study and therefore could have blunted the significance of the aforementioned association; (3) the findings of the present study also need to be confirmed in women and in individuals of other ethnicities. In addition, in countries outside of Asia, carotid-femoral PWV is used as the standard tool to assess arterial stiffness [48]. While brachial–ankle PWV reflects the stiffness of the large- to middle-sized arteries, the carotid-femoral PWV mostly reflects the stiffness of the large arteries. Therefore, confirmation of our findings using carotid-femoral PWV may reinforce the significance of the associations of abnormal glucose metabolism, dyslipidemia and hypertension with macrovascular damage.

In conclusion, conventional risk factors for CVD show heterogeneous longitudinal associations with arterial stiffness and/or abnormal pressure wave reflection. Elevated values of blood pressure showed independent longitudinal associations with both arterial stiffness (macrovascular damage) and abnormal pressure wave reflection, suggesting that BP is also longitudinally associated, at least in part, with microvascular damage. On the other hand, abnormal glucose metabolism and dyslipidemia showed independent longitudinal associations with only arterial stiffness (macrovascular damage).

References

Ohkuma T, Ninomiya T, Tomiyama H, Kario K, Hoshide S, Kita Y, et al. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and the risk prediction of cardiovascular disease: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2017;69:1045–52. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09097.

Ben-Shlomo Y, Spears M, Boustred C, May M, Anderson SG, Benjamin EJ, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity improves cardiovascular event prediction: an individual participant meta-analysis of prospective observational data from 17,635 subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:636–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.063.

Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, O’Rourke MF, Safar ME, Baou K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with central haemodynamics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1865–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq024.

O’Rourke MF, Hashimoto J. Mechanical factors in arterial aging: a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.050.

Tomiyama H, Komatsu S, Shiina K, Matsumoto C, Kimura K, Fujii M, et al. Effect of wave reflection and arterial stiffness on the risk of development of hypertension in Japanese men. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008175. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.008175.

Climie RED, Picone DS, Blackwood S, Keel SE, Qasem A, Rattigan S, et al. Pulsatile interaction between the macro-vasculature and micro-vasculature: proof-of-concept among patients with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118:2455–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-018-3972-2.

Tomiyama H, Yamashina A. Non-invasive vascular function tests: their pathophysiological background and clinical application. Circ J. 2010;74:24–33. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.cj-09-0534.

Rizzoni D, De Ciuceis C, Salvetti M, Paini A, Rossini C, Agabiti-Rosei C, et al. Interactions between macro- and micro-circulation: are they relevant? High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2015;22:119–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40292-015-0086-3.

Climie RE, van Sloten TT, Bruno RM, Taddei S, Empana JP, Stehouwer CDA, et al. Macrovasculature and microvasculature at the crossroads between type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73:1138–49. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11769.

Laurent S, Boutouyrie P. The structural factor of hypertension: large and small artery alterations. Circ Res. 2015;116:1007–21. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303596.

Milwidsky A, Kivity S, Kopel E, Klempfner R, Berkovitch A, Segev S, et al. Time dependent changes in high density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular risk. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173:295–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.03.022.

Bangalore S, Fayyad R, DeMicco DA, Colhoun HM, Waters DD. Body weight variability and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004724. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004724.

Yang J, Zaitlen NA, Goddard ME, Visscher PM, Price AL. Advantages and pitfalls in the application of mixed-model association methods. Nat Genet. 2014;46:100–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2876.

Tomiyama H, Shiina K, Matsumoto-Nakano C, Ninomiya T, Komatsu S, Kimura K, et al. The contribution of inflammation to the development of hypertension mediated by increased arterial stiffness. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;30:e005729. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.005729.

Tomiyama H, Shiina K, Vlachopoulos C, Iwasaki Y, Matsumoto C, Kimura K, et al. Involvement of arterial stiffness and inflammation in hyperuricemia-related development of hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;72:739–45. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11390.

Smulyan H, Lieber A, Safar ME. Hypertension, diabetes type II, and their association: role of arterial stiffness. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpv107.

Cypienė A, Dadonienė J, Rugienė R, Ryliškytė L, Kovaitė M, Petrulionienė Z, et al. The influence of mean blood pressure on arterial stiffening and endothelial dysfunction in women with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicina. 2010;46:522–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina46080075.

Safar ME, Boudier HS. Vascular development, pulse pressure, and the mechanisms of hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:205–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000167992.80876.26.

Tomiyama H, Yamazaki M, Sagawa Y, Teraoka K, Shirota T, Miyawaki Y, et al. Synergistic effect of smoking and blood pressure on augmentation index in men, but not in women. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:122–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2008.20.

Yamashina A, Tomiyama H, Takeda K, Tsuda H, Arai T, Hirose K, et al. Validity, reproducibility, and clinical significance of noninvasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity measurement. Hypertens Res. 2002;25:359–64. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.25.359.

Committee of the Japan Diabetes Society on the Diagnostic Criteria of Diabetes Mellitus, Seino Y, Nanjo K, Tajima N, Kadowaki T, Kashiwagi A, et al. Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2010;1:212–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00074.x.

Horio M, Imai E, Yasuda Y, Watanabe T, Matsuo S. Modification of the CKD epidemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation for Japanese: accuracy and use for population estimates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:32–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.02.344.

Cecelja M, Chowienczyk P. Dissociation of aortic pulse wave velocity with risk factors for cardiovascular disease other than hypertension: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2009;54:1328–36. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137653.

Scuteri A, Morrell CH, Orrù M, Strait JB, Tarasov KV, Ferreli LA, et al. Longitudinal perspective on the conundrum of central arterial stiffness, blood pressure, and aging. Hypertension. 2014;64:1219–27. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04127.

McEniery CM, Spratt M, Munnery M, Yarnell J, Lowe GD, Rumley A, et al. An analysis of prospective risk factors for aortic stiffness in men: 20-year follow-up from the Caerphilly prospective study. Hypertension. 2010;56:36–43. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150896.

Mitchell GF, Conlin PR, Dunlap ME, Lacourcière Y, Arnold JM, Ogilvie RI, et al. Aortic diameter, wall stiffness, and wave reflection in systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51:105–11. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099721.

Zhang M, Bai Y, Ye P, Luo L, Xiao W, Wu H, et al. Type 2 diabetes is associated with increased pulse wave velocity measured at different sites of the arterial system but not augmentation index in a Chinese population. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:622–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.20956.

McEniery CM, Wilkinson IB, Johansen NB, Witte DR, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M, et al. Nondiabetic glucometabolic status and progression of aortic stiffness: the Whitehall II study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:599–606. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-1773.

Zhao X, Wang H, Bo L, Zhao H, Li L, Zhou Y. Serum lipid level and lifestyles are associated with carotid femoral pulse wave velocity among adults: 4.4-year prospectively longitudinal follow-up of a clinical trial. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2018;40:487–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641963.2017.1384486.

Wilkinson IB, Prasad K, Hall IR, Thomas A, MacCallum H, Webb DJ, et al. Increased central pulse pressure and augmentation index in subjects with hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1005–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01723-0.

Wang X, Ye P, Cao R, Yang X, Xiao W, Zhang Y, et al. Triglycerides are a predictive factor for arterial stiffness: a community-based 4.8-year prospective study. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-016-0266-8.

Otsuka T, Kawada T, Ibuki C, Kusama Y. Radial arterial wave reflection is associated with the MEGA risk prediction score, an indicator of coronary heart disease risk, in middle-aged men with mild to moderate hypercholesterolemia. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17:688–94. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.2949.

Wilkinson I, Cockcroft JR. Cholesterol, lipids and arterial stiffness. Adv Cardiol. 2007;44:261–77. https://doi.org/10.1159/000096747.

Prenner SB, Chirinos JA. Arterial stiffness in diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238:370–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.023.

Badhwar S, Chandran DS, Jaryal AK, Narang R, Deepak KK. Regional arterial stiffness in central and peripheral arteries is differentially related to endothelial dysfunction assessed by brachial flow-mediated dilation in metabolic syndrome. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2018;15:106–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479164117748840.

Wen J, Huang Y, Lu Y, Yuan H. Associations of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides and the total cholesterol/HDL-c ratio with arterial stiffness independent of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in a Chinese population. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1223–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0251-5.

Roes SD, Alizadeh Dehnavi R, Westenberg JJ, Lamb HJ, Mertens BJ, Tamsma JT, et al. Assessment of aortic pulse wave velocity and cardiac diastolic function in subjects with and without the metabolic syndrome: HDL cholesterol is independently associated with cardiovascular function. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1442–4. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-0055.

Adams SP, Tiellet N, Alaeiilkhchi N, Wright JM. Cerivastatin for lowering lipids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1:CD012501. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012501.pub2.

Upala S, Wirunsawanya K, Jaruvongvanich V, Sanguankeo A. Effects of statin therapy on arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:338–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.073.

Upadhyay A, Hwang SJ, Mitchell GF, Vasan RS, Vita JA, Stantchev PI, et al. Arterial stiffness in mild-to-moderate CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2044–53. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2009010074.

Tomiyama H, Tanaka H, Hashimoto H, Matsumoto C, Odaira M, Yamada J, et al. Arterial stiffness and declines in individuals with normal renal function/early chronic kidney disease. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:345–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.033.

Tomiyama H, Matsumoto C, Shiina K, Yamashina A, Brachial-Ankle PWV. Current status and future directions as a useful marker in the management of cardiovascular disease and/or cardiovascular risk factors. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23:128–46. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.32979.

Huang J, Chen Z, Yuan J, Zhang C, Chen H, Wu W, et al. Association between body mass index (BMI) and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (bapwv) in males with hypertension: a community-based cross-section study in North China. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:5241–57. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.914881.

Hernandez-Martinez A, Martinez-Rosales E, Alcaraz-Ibañez M, Soriano-Maldonado A, Artero EG. Influence of body composition on arterial stiffness in middle-aged adults: healthy UAL cross-sectional study. Medicina. 2019;55:E334. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070334.

Maple-Brown LJ, Piers LS, O’Rourke MF, Celermajer DS, O’Dea K. Central obesity is associated with reduced peripheral wave reflection in Indigenous Australians irrespective of diabetes status. J Hypertens. 2007;23:1403–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.hjh.0000173524.80802.5a.

Tang B, Luo F, Zhao J, Ma J, Tan I, Butlin M, et al. Relationship between body mass index and arterial stiffness in a health assessment Chinese population. Medicine. 2020;99:e18793. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000018793.

Tomiyama H, Hashimoto H, Tanaka H, Matsumoto C, Odaira M, Yamada J, et al. Continuous smoking and progression of arterial stiffening: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1979–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.042.

Wilkinson IB, Mäki-Petäjä KM, Mitchell GF. Uses of arterial stiffness in clinical practice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:1063–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.313130.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Omron Health Care Company (Kyoto, Japan), Asahi Calpis Wellness Company (Tokyo, Japan) and Teijin Pharma Company (Tokyo, Japan), which awarded funds to Professors Akira Yamashina and Hirofumi Tomiyama.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The sponsor (Omron Health Care Company) assisted in the data formatting (i.e., the data of the brachial–ankle PWV stored in the hard disc of the equipment used for measurement of the brachial–ankle PWV were transferred to an Excel file). Other than this, the company played no role in the design or conduct of the study, i.e., in the data collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data or in the preparation, review or approval of the paper. The authors have no other disclosures to make.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fujii, M., Tomiyama, H., Nakano, H. et al. Differences in longitudinal associations of cardiovascular risk factors with arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection in middle-aged Japanese men. Hypertens Res 44, 98–106 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0523-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0523-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Growth-differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) is associated with arterial stiffness and impaired endothelial function with mediation by albuminuria in the Singapore study of macroangiopathy and microvascular reactivity in type 2 diabetes (SMART2D) cohort

Endocrine (2025)

-

Vascular function: a key player in hypertension

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Differential impact of antihypertensive drugs on cardiovascular remodeling: a review of findings and perspectives for HFpEF prevention

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Vascular functional tests and preemptive medicine

Hypertension Research (2021)

-

Efficacy of intensive lipid-lowering therapy with statins stratified by blood pressure levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and retinopathy: Insight from the EMPATHY study

Hypertension Research (2021)