Abstract

Left atrial enlargement (LAe) is a subclinical marker of hypertensive-mediated organ damage, which is important to identify in cardiovascular risk stratification. Recently, LA indexing for height was suggested as a more accurate marker of defining LAe. Our aim was to test the difference in LAe prevalence using body surface area (BSA) and height2 definitions in an essential hypertensive population. A total of 441 essential hypertensive patients underwent complete clinical and echocardiographic evaluation. Left atrial volume (LAV), left ventricular morphology, and systolic-diastolic function were evaluated. LAe was twice as prevalent when defined using height2 (LAeh2) indexation rather than BSA (LAeBSA) (51% vs. 23%, p < 0.001). LAeh2, but not LAeBSA, was more prevalent in females (p < 0.001). Males and females also differed in left ventricular hypertrophy (p = 0.046) and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) indexes (septal Em/Etdi: p = 0.009; lateral Em/Etdi: p = 0.003; mean Em/Etdi: p < 0.002). All patients presenting LAeBSA also met the criteria for LAeh2. According to the presence/absence of LAe, we created three groups (Norm = BSA−/h2-; DilH = BSA−/h2+; DilHB = BSA+/h2+). The female sex prevalence in the DilH group was higher than that in the other two groups (Norm: p < 0.001; DilHB: p = 0.036). LVH and mean and septal Em/Etdi increased from the Norm to the DilH group and from the DilH to the DilHB group (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). These results show that LAeh2 identified twice as many patients as comparing LAe to LAeBSA, but that both LAeh2 and LAeBSA definitions were associated with LVH and LVDD. In female patients, the LAeh2 definition and its sex-specific threshold seem to be more sensitive than LAeBSA in identifying chamber enlargement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Left atrial (LA) enlargement (LAe) is a frequent finding in hypertensive patients [1]. LAe is recognized as an established type of hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD) since it is associated with the onset of atrial fibrillation and major cardiovascular events [2, 3]. The importance of identifying HMOD in hypertensive patients to stratify their cardiovascular (CV) risk has been strongly underlined [4].

The American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) [5] recommend LA size assessment by the indexation of left atrial end-systolic volume (LAV) by an isometric scaling method: the body surface area (BSA). A LAV indexed to BSA (LAVBSA) cutoff of 34 ml/m2, independent of patient sex, is currently identified as a marker of HMOD [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

The isometric scaling method assumes the presence of a linear relationship between LAV and BSA; however, the relationship between cardiac chamber size and body size has been shown to be nonlinear [13, 14]. Allometric models allow for nonlinear relationships and are shown to be more accurate than isometric models, particularly with obese patients, with whom their use will avoid underestimation of chamber size [15]. Therefore, it has recently been proposed to use height2-indexed LAV (LAVh2) to define LAe [16], as it was able to predict CV events independently from other HMODs [17]. According to these findings, the latest European hypertension guidelines [4] recommended LA size assessment by LAeh2 and provided a sex-specific threshold, similar to what already happens for left ventricle chamber quantification.

The aim of our multicentric study was to determine, in an essential hypertensive population, the differences in LAe prevalence based on different available cutoffs and methodologies (allometric vs isometric and sex-specific vs non-sex-specific).

Methods

Four hundred eighty-four hypertensive patients were enrolled in the multicentric ARGO-SIIA project (Aortic RemodellinG in hypertensiOn of the Italian Society of Hypertension) [18]. All patients were evaluated during their first visit for hypertension with the specific aim of assessing target organ damage. The exclusion criteria were age less than 18 years, poor echocardiographic image quality, known aortic dilatation, pregnancy, comorbidities independently impacting or promoting aortic media degeneration (cocaine use, polycystic kidney disease, collagenopathies such as Marfan, Ehlers–Danlos, or Loeys Dietz syndromes and Turner syndrome), bicuspid aorta, significant (more than mild) valvulopathy, and secondary hypertension.

All patients underwent blood pressure measurements according to European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology (ESC/ESH) [4] recommendations. All measures were performed using a manual sphygmomanometer with an appropriately sized cuff with study participants in the sitting position after a 5-min rest in a quiet room. The average of three consecutive measures was used in all the analyses. Height (in meters) and weight (in kilograms) were measured at the time of echo examination. BMI was obtained as weight/height2, while BSA was calculated using the Dubois & Dubois formula: BSA = 0.20247 [weight 0.425 × (height/100)0.725] [19].

The study was approved by our local ethics committee (Comitato Etico Interaziendale A.O.U. Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino - A.O. Ordine Mauriziano - A.S.L. CDT - CEI/330), and all patients provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

A total of 43 patients were excluded from the present analysis due to suboptimal image quality for LAV assessment. Thus, the study population comprised 441 hypertensive patients.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed by experienced operators following current guidelines [5] and a standardized protocol. Left ventricular (LV) mass (LVM) was estimated from the end-diastolic left ventricular internal diameter (LVIDd), interventricular septum and inferolateral wall thickness (ILW) by the cube formula [5] and was indexed to BSA to obtain the left ventricular mass index (LVMI). The relative wall thickness (RWT) was calculated as (2·ILW)/LVIDd [5]. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as LVMI greater than 95 g/m2 in women or greater than 115 g/m2 in men, whereas patterns of left ventricular geometry were defined according to ESC/ESH [4] recommendations. LAV was estimated from the LA area in 4-chamber and 2-chamber views and from the shortest of the two LA long axes measured in the apical 2- and 4-chamber views by the area-length technique [5]. LAV was then indexed to BSA and height2. LAe was defined according to both the current ASA/EACVI [5] (LAeBSA: LAV indexed to BSA (LAVBSA) > 34 ml/m2) and ESC/ESH hypertension guidelines [4] (LAeh2: LAV indexed to height2, LAVh2, >18.5 ml/m2 in males and >16.5 ml/m2 in females). Diastolic function was estimated indirectly according to current guidelines and expressed as septal, lateral, and mean Em/Etdi [20].

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, v25 for Mac OSX, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The distribution of the variables was analyzed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Q–Q graph. Data are presented as the mean ± SD or median and interquartile range and as numbers and percentages as appropriate. We compared continuous variables using t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) when the distribution was normal and Kruskal–Wallis or nonparametric ANOVA for nonnormally distributed variables. We performed a post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni test. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. The agreement between LAe definitions was assessed through the K statistic. Ratiometric scaling of different indexes was tested by linear regression. ROC curves were used to identify the sensitivity and specificity of BSA indexing compared to height2 indexing, and the Youden test was used to identify the most accurate cutoff. Statistical significance was assumed if the null hypothesis could be rejected at a p value less than 0.05.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the study population divided by sex; 229 patients (51.9% of the study population) were male, and the mean age was 60.2 ± 14.9 years, without significant sex differences. Male patients were more frequently overweight (49.8% vs. 35.4%, p = 0.003), while no differences were observed in obesity (24.5% vs. 27.4%, p = 0.557), dyslipidemia (40.2% vs. 31.6%, p = 0.061) or diabetes type 2 rates (11.8% vs. 8.5%, p = 0.253). Evaluating pharmacotherapy, only ß blocker intake was significantly different among male patients compared to female patients (27.9% vs. 38.7%, p = 0.016, Supplementary Table 1).

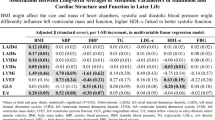

Echocardiographic characteristics are presented in Table 2. The average LAVh2 was 19.0 ± 7.5 ml/m2 whereas the mean LAVBSA was 28.6 ± 10.8 ml/m2. Atrial dimensions, as assessed by both LAVh2 and LAVBSA, were not significantly different between sexes in the whole study population (LAVh2: 18.9 ± 7.2 vs. 19.2 ± 7.8, p = 0.643; LAVBSA: 28.6 ± 10.7 vs. 28.5 ± 10.9, p = 0.877), or in different age classes (Supplementary Table 2), which we identified by tertiles.

In contrast, other parameters were significantly different in male and female patients, respectively: LVH (23.6% vs. 32.1%, p = 0.046), LVMI (99.8 ± 27.9 vs. 87.3 ± 23.1, p < 0.001) and LVDD index (septal Em/Etdi: 10.4 ± 4.6 vs. 11.5 ± 3.9, p = 0.009; lateral Em/Etdi: 7.8 ± 3.1 vs. 8.9 ± 4.5, p = 0.003; mean Em/Etdi: 8.8 ± 3.2 vs. 9.8 ± 3.4, p < 0.002).

The prevalence of LAe was significantly influenced by the chosen methods, and in particular, it was twice as prevalent when using height2 indexation rather than BSA (50.6% vs. 23.4%, p < 0.001). Similarly, LAeh2, but not LAeBSA, was more common in females (59.0% vs. 42.8%, p = 0.001).

The K statistic between the LAeh2 and LAeBSA definitions reported a κ of 0.46 (p < 0.001). All subjects who met the criteria for LA dilatation based on BSA indexation also met the criteria based on height2 indexation, while the opposite was not true. Therefore, we divided the study population into three groups: Normal (Norm; subjects with no LAe), Dilated based on height criteria (DilH; LAeh2 but not LAeBSA) and dilated based on both criteria (DilHB; both LAeBSA and LAeh2). The clinical and echocardiographic features of these groups are described in Tables 3 and 4.

The percentage of women in the DilH group (62.5%) was higher than that in both the Norm (39.9%, p < 0.001) and DilHB (46.6%, p = 0.036) groups, while the sex distribution was comparable between the Norm and DilHB groups (p = 0.180).

We observed a progressive increase in the prevalence of LVH among the three groups (Norm 13.8%, DilH 34.2%, and DilB 49.5%—all p < 0.050). A similar relationship was also observed for diastolic impairment (septal Em/Etdi—p < 0.001 for both comparisons; mean Em/Etdi—p < 0.050 for both comparisons).

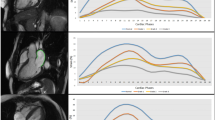

As shown in Fig. 1, the study population was split by BMI class (normal, overweight and obese) to check whether indexing to BSA brought to an underestimation of LAe prevalence. The LAeh2 prevalence was significantly higher than the LAeBSA prevalence in each class (BMI < 25: p < 0.001; BMI 25–30: p < 0.001; BMI > 30: p < 0.001). The ratios between prevalences decreased along BMI classes from normal to obese (BMI < 25:3.1; BMI25–30:2.0; BMI > 30:1.9). Indexing LAV to height2 did not erase the influence of height on LAV (Fig. 2a), while indexing to BSA seemed to be more effective in this purpose (Fig. 2b).

LAV indexations for height2 and BSA were highly correlated (R = 0.98, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The threshold of LAVBSA that more accurately reproduced the LAeh2 definition was 28.0 ml/m2 in males and 25.0 ml/m2 in females.

Scatter plot of left atrial volume indexed to BSA (LAV/BSA) against left atrial volume (LAV) indexed to height2 (LAV/h2). Vertical purple dashed line represents LAeBSA current threshold. Horizontal blue and red dashed lines represent current LAeh2 thresholds (male and female respectively). Vertical blue and red dashed lines represent LAeBSA thresholds corresponding to LAeh2 ones (male and female respectively)

Discussion

The present study provides data from a population of 60-year-old hypertensive individuals.

We performed a comparative analysis between two different methods proposed to define LAe: height2 [4, 16] and BSA [5] indexation. According to the K statistic, these two definitions showed moderate agreement [21]. Nevertheless, we found that height2 indexation to define LAe resulted in doubling LAe prevalence compared to BSA indexation. Interestingly, the difference between these two definitions lies not only in the different sensibilities and specificities due to the method-specific threshold, but also in the presence of a different ability to detect LAe in females. Indeed, in our population, LAe was significantly more prevalent in female patients than in male patients when using height2, while LAeBSA use did not lead to a significant intersex difference in LAe prevalence.

LAe has been proven to be an early echocardiographic sign of hypertension [1], and its development is thought to be an early marker of LVDD compared to, for example, resting Em/Etdi. The higher rate of LVH and the worse LV diastolic function we observed in females seemed to be consistent with the higher rate of LAeh2 observed in the same sex group. Within our hypertensive population, both LAVBSA and LAVh2 were similar between male and female patients.

Previously, different studies aimed to verify whether LAVBSA differed between males and females in healthy populations, and most of them did not find any differences [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. On the other hand, Rønningen et al. [22]. found that males presented higher LAVBSA values than females. They suggested that their results may be explained by their older population compared to previous studies and by the fact that sex differences in LAVBSA may be observed only in older subjects. In our sample, these differences were not present in any of the age classes identified by tertiles, even in the group of patients >70 years. However, it must be pointed out that ours was a hypertensive population and that we found worse diastolic function in the female cohort. Thus, it is plausible that female LAV was affected by these factors—hypertension and diastolic dysfunction—not allowing us to observe differences in LAVBSA or LAVh2. Other evidence [16] highlights the presence of a sex difference regarding indexed atrial size values, both LAVBSA and LAVh2. In their study, Kuznetsova et al. underlined the importance of using sex-specific thresholds to detect cardiac dimension enlargement, and we feel that we agree with them. Actually, in patients presenting only LAeh2, which has a sex-specific threshold, we found a higher rate of LVH (sex-specific too) and worse diastolic function than in subjects without LAe (Norm). Furthermore, compared to patients with no LAe or LAe BSA and LAe h2, the group of patients with LAeh2 only had a significantly higher proportion of female patients. These results suggest the presence of hypertensive females with LA dilatation that are identified only by scaling to height2. The LAeh2 definition and its sex-specific threshold seem to be more sensitive than LAeBSA in identifying chamber enlargement, at least in the female cohort.

In their study, Kuznetsova et al. [16]. also compared different scaling methods that could be applied to LAVs. Height2 was found to be more sensitive in detecting LAe, particularly in overweight and obese patients, than BSA, which seemed to underestimate LA dimensions due to body weight. In our study, scaling LAe to BSA erased the influence of BSA, while the same was not true for height2. The goodness of BSA indexation was also confirmed in the overweight and obese subgroups (data not shown). It is highly likely that our hypertensive population accounted for these results: actually, the higher LVMI and worse diastolic function presented by hypertensive patients compared to healthy individuals may have masked the underestimation effect of BSA in patients with elevated BMI.

The LAeh2 definition proposed by the latest hypertension guidelines [4] presents, as mentioned, 2 sex-specific thresholds: 18.5 ml/m2 for males and 16.5 ml/m2 for females, as obtained by the distribution of LAVh2 in normal European subjects [16]. In our population, a similar accuracy in defining LAe was obtained by modifying the LAeBSA definition as follows: 29.0 ml/m2 for males and 25.0 ml/m2 for females. These new thresholds are very similar to the old LAeBSA definition of 28.0 ml/m2 [23], which was subsequently changed in the updated ASA/EACVI recommendations [5]. The LAe definition proposed by hypertension guidelines [4] is innovative since it suggests the use of a new allometric scaling system but goes in the opposite direction of international guidelines, which have recently increased the value of LAV thresholds to define LAe [22, 24]. It must be highlighted that the LAe definition in current hypertension guidelines is based on LAV obtained by the prolate-ellipsoid method adopted by Kuznetsova in his study [16]. This method is known to underestimate the LA dimension [5, 25], and this fact could explain the high sensitivity we found with the height2 scaling definition of LAe.

Further prospective studies will be needed to establish threshold values appropriate for CV risk stratification, addressing the prognostic value of cutoff values obtained by different indexations.

Limits

This study has some limitations. Since it is a prevalence observational study, our results derive from a simple observation of the population and do not allow us to establish which method or which type of cutoff (unique or sex-specific) is superior in terms of risk stratification. However, we can highlight the differences we observed and advance hypotheses that can explain them. Moreover, most of the patients were under antihypertensive treatment, and several variables, such as LAV [26] and LVM [27], could be affected by this fact.

Conclusion

LAe can be twice as prevalent in the hypertensive population when defined using height2 indexation rather than BSA. In female hypertensive patients, the LAeh2 definition and its sex-specific threshold seem to be more sensitive than LAeBSA in identifying chamber enlargement. A sex-specific cutoff might be desirable for defining LAe, although prospective studies will be needed to evaluate its predictive value for hypertension-related CV events.

References

Milan A, Puglisi E, Magnino C, Naso D, Abram S, Avenatti E, et al. Left atrial enlargement in essential hypertension: role in the assessment of subclinical hypertensive heart disease. Blood Press. 2012;21:88–96. https://doi.org/10.3109/08037051.2011.617098.

De Simone G, Izzo R, Chinali M, De Marco M, Casalnuovo G, Rozza F, et al. Does information on systolic and diastolic function improve prediction of a cardiovascular event by left ventricular hypertrophy in arterial hypertension? Hypertension. 2010;56:99–104. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150128.

Pritchett AM, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ, Karon BL, Redfield MM. Diastolic dysfunction and left atrial volume: a population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.054.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;00:1–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339.

Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:233–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jev014.

Cacciapuoti F, Scognamiglio A, Paoli VD, Romano C, Cacciapuoti F. Left atrial volume index as indicator of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction: comparation between left atrial volume index and tissue myocardial performance index. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;20:25–9. https://doi.org/10.4250/jcu.2012.20.1.25.

Orban M, Bruce CJ, Pressman GS, Leinveber P, Romero-Corral A, Korinek J, et al. Dynamic changes of left ventricular performance and left atrial volume induced by the mueller maneuver in healthy young adults and implications for obstructive sleep apnea, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1557–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.07.050.

Whitlock M, Garg A, Gelow J, Jacobson T, Broberg C. Comparison of left and right atrial volume by echocardiography versus cardiac magnetic resonance imaging using the area-length method. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1345–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.06.065.

Yoshida C, Nakao S, Goda A, Naito Y, Matsumoto M, Otsuka M, et al. Value of assessment of left atrial volume and diameter in patients with heart failure but with normal left ventricular ejection fraction and mitral flow velocity pattern. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:278–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejechocard/jen234.

Iwataki M, Takeuchi M, Otani K, Kuwaki H, Haruki N, Yoshitani H, et al. Measurement of left atrial volume from transthoracic three-dimensional echocardiographic datasets using the biplane Simpson’s technique. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:1319–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2012.08.017.

Yamaguchi K, Tanabe K, Tani T, Yagi T, Fujii Y, Konda T, et al. Left atrial volume in normal Japanese adults. Circ J. 2006;70:285–8. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.70.285.

Kou S, Caballero L, Dulgheru R, Voilliot D, De Sousa C, Kacharava G, et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal cardiac chamber size: results from the NORRE study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:680–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jet284.

Gutgesell HP, Rembold CM. Growth of the human heart relative to body surface area. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:662–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(90)91048-B.

Tanner J. Fallacy of per-weight and per-surface area standards, and their relation to spurious correlation. J Appl Physiol. 1949;2:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1949.2.1.1.

Zong P, Zhang L, Shaban NM, Peña J, Jiang L, Taub CC. Left heart chamber quantification in obese patients: How does larger body size affect echocardiographic measurements? J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:1267–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2014.07.015.

Kuznetsova T, Haddad F, Tikhonoff V, Kloch-Badelek M, Ryabikov A, Knez J, et al. Impact and pitfalls of scaling of left ventricular and atrial structure in population-based studies. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1186–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000922.

Mancusi C, Canciello G, Izzo R, Damiano S, Grimaldi MG, de Luca N, et al. Left atrial dilatation: a target organ damage in young to middle-age hypertensive patients. The Campania Salute Network. Int J Cardiol. 2018;265:229–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.120.

Milan A, Degli Esposti D, Salvetti M, Izzo R, Moreo A, Pucci G, et al. Prevalence of proximal ascending aorta and target organ damage in hypertensive patients: the multicentric ARGO-SIIA project (Aortic RemodellinG in hypertensiOn ofthe Italian Society ofHypertension). J Hypertens. 2019;37:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000001844.

Du Bois D, Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Nutrition. 1916;5:303–11.

Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:1321–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jew082.

Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall; 1991.

Rønningen PS, Berge T, Solberg MG, Enger S, Nygård S, Pervez MO, et al. Sex differences and higher upper normal limits for left atrial end-systolic volume in individuals in their mid-60s: data from the ACE 1950 Study. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;0:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jeaa004.

Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s guidelines and standards committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiograph. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005.

Badano LP, Muraru D, Parati G. Do we need different threshold values to define normal left atrial size in different age groups? Another piece ofthe puzzle of left atrial remodelling with physiological ageing Luigi. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;0:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jeaa024.

Ujino K, Barnes ME, Cha SS, Langins AP, Bailey KR, Seward JB, et al. Two-dimensional echocardiographic methods for assessment of left atrial volume. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1185–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.040.

Gerdts E, Oikarinen L, Palmieri V, Otterstad JE, Wachtell K, Boman K, et al. Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) Study. Correlates of left atrial size in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) Study. Hypertension. 2002;39:739–43. https://doi.org/10.1161/hy0302.105683.

Fagard RH, Celis H, Thijs L, Wouters S. Regression of left ventricular mass by antihypertensive treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized comparative studies. Hypertension. 2009;54:1084–91. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.136655.

The Working Group on Heart and Hypertension of the Italian Society of Hypertension.

Lorenzo Airale1,, Anna Paini2, Eugenia Ianniello3, Costantino Mancusi4, Antonella Moreo5, Gaetano Vaudo6, Eleonora Avenatti1, Massimo Salvetti2, Stefano Bacchelli3, Raffaele Izzo4, Paola Sormani5, Alessio Arrivi6, Maria Lorenza Muiesan2, Daniela Degli Esposti3, Cristina Giannattasio5, Giacomo Pucci6, Nicola De Luca3, Alberto Milan1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the Working Group on Heart and Hypertension of the Italian Society of Hypertension are listed above References.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Airale, L., Paini, A., Ianniello, E. et al. Left atrial volume indexed for height2 is a new sensitive marker for subclinical cardiac organ damage in female hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res 44, 692–699 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00614-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00614-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Subclinical left ventricular systolic impairment in hypertensive patients: insights from 2d speckle-tracking echocardiography

Journal of Human Hypertension (2025)

-

Denervation or stimulation? Role of sympatho-vagal imbalance in HFpEF with hypertension

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Prognostic association supports indexing size measures in echocardiography by body surface area

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Update on Hypertension Research in 2021

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Looking at the best indexing method of left atrial volume in the hypertensive setting

Hypertension Research (2021)