Abstract

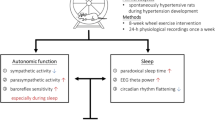

Increased blood pressure (BP) caused by exposure to cold temperatures can partially explain the increased incidence of cardiovascular events in winter. However, the physiological mechanisms involved in cold-induced high BP are not well established. Many studies have focused on physiological responses to severe cold exposure. In this study, we aimed to perform a comprehensive analysis of cardiovascular autonomic function and sleep patterns in rats during exposure to mild cold, a condition relevant to humans in subtropical areas, to clarify the physiological mechanisms underlying mild cold-induced hypertension. BP, electroencephalography, electromyography, electrocardiography, and core body temperature were continuously recorded in normotensive Wistar-Kyoto rats over 24 h. All rats were housed in thermoregulated chambers at ambient temperatures of 23, 18, and 15 °C in a randomized crossover design. These 24-h physiological recordings either with or without sleep scoring showed that compared with the control temperature of 23 °C, the lower ambient temperatures of 18 and 15 °C not only increased BP, vascular sympathetic activity, and heart rate but also decreased overall autonomic activity, parasympathetic activity, and baroreflex sensitivity in rats. In addition, cold exposure reduced the delta power percentage and increased the incidence of interruptions during sleep. Moreover, a correlation analysis revealed that all of these cold-induced autonomic dysregulation and sleep problems were associated with elevation of BP. In conclusion, mild cold exposure elicits autonomic dysregulation and poor sleep quality, causing BP elevation, which may have critical implications for cold-related cardiovascular events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low ambient temperatures contribute to the increased incidence of cardiovascular events during winter [1,2,3]. Moreover, seasonal variations in blood pressure (BP) have been reported in persons with [4,5,6] and without hypertension [7]. BP is lower in the summer and higher in the winter according to measurements obtained both in clinical settings [4] and through ambulatory monitoring [6,7,8]. The association of cardiovascular event occurrence with low ambient temperature and high BP has been demonstrated in studies [9, 10]. However, the underlying physiological mechanisms of cold-induced high BP are multiple and not yet fully understood.

The autonomic nervous system strictly regulates BP variation within a narrow range. Increased sympathetic activity together with decreased parasympathetic activity may lead to the development of hypertension [11]. In addition, the baroreflex, the dominant short-term control mechanism for BP [12], buffers changes in BP by mediating the parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves to the peripheral blood vessels and heart. A decrease in baroreflex sensitivity is associated with cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and carries a poor prognosis [12,13,14]. However, sleep is characterized by important changes in the circadian rhythm of heart rate and BP induced by declining sympathetic activity and increasing parasympathetic activity and baroreflex sensitivity during sleep [14, 15]. Therefore, sleep loss may induce sympathetic overactivity and reduced baroreflex sensitivity associated with increased heart rate and BP, thereby increasing the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [16, 17]. According to previous studies, exposure to cold temperature affects autonomic nervous system function [18,19,20], baroreflex sensitivity [21, 22], and sleep quality [23,24,25]. However, most previous studies have been conducted without long-term, simultaneous, continuous measurements of sleep patterns and cardiovascular autonomic regulation during cold exposure; thus, some of the findings are contradictory and inconsistent [18, 22, 26,27,28]. Therefore, the effects of ambient temperature changes, autonomic function, the baroreflex, and sleep patterns on BP control have not been established comprehensively and conclusively.

Many human and rodent studies have focused on the physiological and pathophysiological responses to severe cold exposure [18, 19, 21, 28]. However, the ambient temperature during winter in a subtropical zone, such as in Taiwan, is ~10–20 °C, which is defined as mild cold exposure; nevertheless, cardiovascular events in Taiwan occur significantly more frequently during winter than they do at other times of year [29]. Therefore, the aims of the present study were as follows: (1) to use an animal model and a climate model mimicking the winter season in Taiwan (18 and 15 °C) to study whether mild cold exposure would induce a marked change in BP and (2) to explore sleep pattern changes, autonomic function, and the baroreflex during sleep–wake cycles and whether they have critical effects on BP during a mild cold exposure intervention. We hypothesized that during mild cold exposure, rats would show cardiovascular autonomic dysregulation and sleep problems that might result in increased BP.

Material and methods

Animal preparation

Experiments were performed on male normotensive Wistar-Kyoto rats 10–12 weeks old (n = 11). The rats employed in this study were obtained from Taiwan’s National Yang-Ming University’s Animal Center in accordance with the stipulated recommendations contained in the Position of the American Heart Association on Research Animal Use. Regarding the rats’ housing, they lived in groups in a sound-attenuated room that followed a light–dark cycle of 12:12 h (lights on from 10:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m.). In this study, we considered Zeitgeber time (ZT) 0 to represent lights on, and we considered ZT 12 to represent lights off. The room was maintained at an appropriate humidity (40–70%) and temperature (22 ± 2 °C). National Yang-Ming University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the experimental procedures. All rats underwent surgery for physiological signal collection.

Surgical procedures

Electrodes were implanted in the rats at 8–10 weeks of age. Each rat was anesthetized using pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection), and after being positioned in a regular stereotaxic apparatus, each of them underwent parietal electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), and nuchal electromyography (EMG) electrode implantation [14]. Moreover, thermistors were implanted in the rats’ abdomens for core body temperature (CBT) signal collection. For each rat, electrodes were connected to a permanently affixed head stage on the skull. Using an abdomen-implanted telemetry transmitter (HD-S10; Data Sciences, St. Paul, MN, USA), we collected arterial pressure signals from the tip of an arterial catheter; this catheter had been inserted into the abdominal aorta [14, 30]. Postoperatively, an antibiotic (cephalexin hydrate, 15 mg/kg, subcutaneous injection) and an analgesic (carprofen, 5 mg/kg, subcutaneous injection) were administered twice daily, with the corresponding rats being individually housed for a 1-week period to recover and habituate to single housing for subsequent physiological recordings.

Experimental protocols

The experiments used 11 rats and started at least 7 days after surgery. In order to habituate the rats to the experimental apparatus, they were placed individually in a recording chamber for at least 1 day before physiological recording. The physiological signals were recorded individually at 23, 18, and 15 °C for 1 day each, separated by 1- to 2-day washout periods during which the ambient temperature was maintained at 23 °C. Moreover, the order of the recording days at three ambient temperatures was a crossover design for each rat (Supplementary Fig. 1). The recording chamber was nontranslucent and consisted of a light and a thermoelectric module controlled by a microcontroller to adjust the light–dark cycle and ambient temperature. Each rat was recorded individually in the recording chamber at a specific and static ambient temperature. After the physiological recordings were finished, rats were sacrificed immediately with an overdose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection).

Measurements

A KY4C wireless sensor from K&Y Lab (Taipei, Taiwan) with dimensions of 25 × 21 × 18.5 mm3 and a mass of 8.3 g was used to record electrophysiological signals. The telemetry system’s performance has been validated previously [31]. Wireless sensors were mounted on the rats’ heads to record EEG, EMG, and ECG signals; CBT; and three-dimensional acceleration. In addition, for signal processing, ECG, EMG, and EEG signals were filtered at 0.72–103, 34–103, and 0.16–48 Hz, respectively, and amplified 500-, 1000-, and 1000-fold, respectively [31]. Acceleration in the anteroposterior (X), mediolateral (Y), and vertical (Z) dimensions was detected using an ADXL330 triaxial accelerometer developed by Analog Devices Inc. (Norwood, MA, USA). Acceleration in a range of –3 to +3 g was detected on each axis [31]. For these signals, filtration was executed using a direct current at 29 Hz. The CBT was detected using a thermistor (503ET-3H; SEMITEC, Tokyo, Japan) with resistance-to-voltage conversion circuits, each detecting temperatures between 30 and 40 °C. An analog–digital converter was used for synchronous ECG, EEG, CBT, EMG, and three-dimensional acceleration signal digitization at sampling rates of 500, 125, 50, 250, and 62.5 Hz, respectively. A KY3 digital data recorder derived from K&Y Lab then received the digitized signals at a 2.4-GHz radio frequency. A particular receiver (CATALOG# 272-6001), developed by Data Sciences, wirelessly received arterial pressure signals that were run through a KY2 pulse-interval–voltage converter (K&Y Lab) for conversion into continuous waveforms. Subsequently, one data recorder (KY3) was used to synchronously digitize the arterial pressure waveforms with the electrophysiological signals at 500 Hz. A flash memory card stored all digitized data for subsequent offline analysis. The CBT data of four rats were excluded because of failed data collection during experiments.

Sleep and EEG frequency analysis

On the basis of EEG and EMG data, the rats’ sleep and wake stages were classified as described previously [32]. For the EEG and EMG signals, we executed continuous power spectral analysis by using a 16-s Hamming window (50% overlap). This analysis quantified the EEG mean power frequency (MPF) and the EMG power magnitude. A temporal resolution of 8 s was obtained for sleep scoring. States of consciousness were defined for each time epoch as follows by using specified TMPF and TEMG thresholds: quiet sleep (QS), paradoxical sleep (PS), and active waking (AW). For each rat and 6-h window, an experienced investigator performed visual inspections to adjust TMPF and TEMG. One sleep–wake stage comprised at least six consecutive identical epochs (~56 s), and interruptions were defined by the occurrence of fewer than six consecutive epochs. Because they are inherent to sleep, interruptions were included along with the sleep stage during which they occurred. Stage time (total time spent in a specific stage during analysis), bout number (number of bouts for a specific stage), and bout duration (average duration of bouts for a particular stage) were calculated to quantify sleep–wake stage structure. Moreover, the delta power percentage (0.5–4 Hz) [33] was used to assess sleep quality and QS interruptions.

Cardiovascular variability analysis

The procedures for cardiovascular variability analysis were as previously described [14]. In brief, the waxing and waning of each arterial pulsation were detected by our computer algorithm to define systolic and diastolic BP. Through the integration of the arterial pulse contour, we derived the mean arterial pressure (MAP). ECG signal preprocessing was designed in accordance with suggested procedures for analyzing heart rate variability [34]. During the process of QRS complex identification, the computer employed for the task used a spike-detection algorithm that was similar to those used for general QRS detection to identify all digitized ECG signal peaks. Spikes were measured in terms of amplitude and duration to enable mean and standard deviation calculations to be standard QRS templates. Subsequently, QRS complexes were identified, and individual ventricular premature complexes or noise was rejected on the basis of their likelihood relative to the standard QRS templates. For each valid QRS complex, the R point was the time point of the heartbeat; the interval that was observed between two consecutive R points was defined as the RR interval. Temporary means as well as standard deviations for all RR intervals were derived and subsequently served as a standard reference during RR rejection. Validation for each RR proceeded as follows: RR values with standard scores >3 were considered nonstationary or erroneous and were rejected. MAP rejection was performed in an identical manner. To provide continuity in the time domain, stationary RR and MAP data were resampled and interpolated at 64 Hz, then truncated into 16-s segments with 50% overlap. A fast Fourier transform was executed to analyze these sequences after the application of the Hamming window. The MAP spectrogram’s low-frequency power (BLF, 0.06–0.6 Hz) and the RR spectrogram’s high-frequency power (HF, 0.6–2.4 Hz), normalized low-frequency power (LF%, 0.06–0.6 Hz), and total power (TP) were quantified. BLF represented sympathetic vasomotor activity. HF, LF%, and TP represented cardiac vagal activity, cardiac sympathetic modulation, and overall cardiac autonomic activity, respectively [14, 34].

MAP-RR linear regression was used to estimate spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity as previously described [14, 35]. The calculated baroreflex sensitivity of ascending (descending) MAP-RR pairs (BrrA (BrrD)) was the slope of the linear regression between simultaneously ascending (descending) MAP-RR pairs for the sequence analysis. Slope was calculated using at least three beats, and slopes were valid if the MAP and RR were highly correlated (r > 0.85) [35,36,37,38]. For the sequence analysis, the length of the data sample was 56 s.

Statistical analysis

BLF, TP, and HF were transformed using natural logarithms for skewness correction [39]. We executed the Shapiro–Wilk test to formally test normality for all variables. To compare changes in variables induced by the two reduced ambient temperatures, we executed a paired t-test if normality was not rejected after the Shapiro–Wilk test; otherwise, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was preferred. In order to compare the effects of the three ambient temperatures or the different sleep–wake states, Fisher’s least significant difference test was performed following a significant one-way analysis of variance with repeated-measures if normality was not rejected after the Shapiro–Wilk test; otherwise, Dunn’s post hoc method following a significant Friedman’s test was preferred. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the correlation between two parameters. The coefficient of determination (r2) was used to indicate the percentage of the variance in the dependent variable that could be explained by the regression equation. Differences between values and zero were assessed using a one-sample t-test or a one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test for normally and nonnormally distributed variables, respectively. Data are shown as the means ± SEM. Statistical significance is defined as p < 0.05.

Results

To explore the changes in physiological parameters in rats at ambient temperatures of 23, 18, and 15 °C, we continuously and simultaneously analyzed not only CBT but also various physiological signals for 24 h (Fig. 1). No significant differences were noted in the mean CBT over the 24-h recording without sleep staging among the three ambient temperatures. After sleep stages were distinguished, the rats had a slightly higher CBT at 15 °C than at 23 °C. The difference in CBT between these two ambient temperatures was ~0.2 °C, but this difference was present only during PS and not in other sleep stages (Supplementary Table 1).

Continuous and simultaneous analysis of sleep–wake state, arterial pressure variability, heart rate variability, and core body temperature (CBT) over a 12-h light period (white bar) and 12-h dark period (black bar) for one rat at different ambient temperatures of 23, 18, and 15 °C. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and R-R intervals (RR) and their power spectrograms (BPSD and HPSD) are displayed with temporal alterations in low-frequency power (BLF) of arterial pressure variability and total power (TP), high-frequency power (HF), and normalized low-frequency power (LF%) of heart rate variability. The ranges of frequencies for the BLF, HF, and LF are denoted on the right side of the spectrograms. The sleep stages (Stage) included active waking (AW), quiet sleep (QS), and paradoxical sleep (PS). Interruptions of QS are marked by vertical ticks on the hypnogram. ln natural logarithm, nu normalized units, ZT Zeitgeber time

Effects of low temperature on MAP and RR during different sleep–wake stages

Compared with the control temperature of 23 °C, at the lower temperatures of 18 and 15 °C, the rats showed increased MAP both with and without sleep staging. In addition, during QS and PS, the MAP was even higher at 15 °C than at 18 °C. Moreover, a lower RR was observed at the lower temperatures of 18 and 15 °C than at 23 °C, and the comparison of 18 and 15 °C revealed that RR was even lower at 15 °C than at 18 °C, regardless of whether the sleep stage was distinguished, indicating that RR was lowest at 15 °C among the three ambient temperatures (Fig. 2A). To further explore whether the effects of low ambient temperature on MAP and RR were different between sleep–wake stages, the changes in MAP and RR from 23 to 18 °C and from 23 to 15 °C during the AW, QS, and PS stages were calculated (Fig. 2B). The changes in MAP and RR induced by temperatures of 18 and 15 °C were prominent during all sleep–wake stages, and changes induced by a temperature of 15 °C in both MAP and RR were much greater than those induced by 18 °C mainly during sleep (QS and PS). Moreover, comparison of the changes between sleep and wakefulness revealed that 18 °C induced more changes in RR during QS than during AW and that 15 °C induced more changes in not only RR but also MAP during either QS or PS than during AW.

A Effects of different ambient temperatures (23, 18, and 15 °C) on the mean arterial pressure (MAP) and R-R intervals (RR) of 24-h recordings without sleep scoring (Mix) and with distinctions among active waking (AW), quiet sleep (QS), and paradoxical sleep (PS) in rats. *p < 0.05 vs 23 °C, †p < 0.05 vs 18 °C by Fisher’s least significant difference test following a significant one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA); *p < 0.05 vs 23 °C, †p < 0.05 vs 18 °C by Dunn’s post hoc method following a significant Friedman’s test. B The changes in MAP and RR from 23 to 18 °C (18–23 °C) and from 23 to 15 °C (15–23 °C) during the AW, QS, and PS stages. All variables were normally distributed. *p < 0.05 vs 0 by one-sample t-test; †p < 0.05 vs 18–23 °C by paired t-test; #p < 0.05 vs AW by Fisher’s least significant difference test. Data are shown as scatter/dot plots with means ± SEM; n = 11

Effects of low temperature on cardiovascular variability indices during different sleep–wake stages

A comparison of the three ambient temperatures showed that BLF was significantly higher at 15 °C than at 23 and 18 °C for the whole day, except during PS. Moreover, TP and HF were lowest at 15 °C among the three ambient temperatures without sleep staging and across all sleep–wake stages, except that no difference was determined between 18 and 15 °C during QS. By contrast, LF% at 15 °C was significantly reduced only during AW (Fig. 3A). In the case of the low-temperature-induced changes in cardiovascular autonomic variables during different sleep–wake stages, only 15 °C induced significant changes in BLF during AW and QS, and no ambient temperature induced significant BLF changes during PS. Moreover, the changes induced by a temperature of 18 °C in TP and HF were prominent only during AW, and those from 15 °C were prominent during not only AW but also sleep stages; in addition, 15 °C induced more changes than 18 °C, mainly during AW and PS. However, no significant differences were noted in changes induced by 18 and 15 °C between wake and sleep stages. In contrast to the obvious changes in TP and HF, the significant changes in LF% were induced only by 15 °C during AW, and the changes during AW were significantly different from those during sleep stages (Fig. 3B).

A Effects of different ambient temperatures (23, 18, and 15 °C) on cardiovascular autonomic variables of 24-h recording without sleep scoring (Mix) and with distinctions among active waking (AW), quiet sleep (QS), and paradoxical sleep (PS) in rats. *p < 0.05 vs 23 °C, †p < 0.05 vs 18 °C by Fisher’s least significant difference test following a significant one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA); *p < 0.05 vs 23 °C, †p < 0.05 vs 18 °C by Dunn’s post hoc method following a significant Friedman’s test. B The changes in cardiovascular autonomic variables from 23 to 18 °C (18–23 °C) and from 23 to 15 °C (15–23 °C) during the AW, QS, and PS stages. *,*p < 0.05 vs 0 by one-sample t-test for normality and one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonnormality, respectively; †,†p < 0.05 vs 18–23 °C by paired t-test for normality and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonnormality, respectively; #p < 0.05 vs AW by Dunn post hoc method for nonnormality; there was no significant difference between AW and either QS or PS by Fisher’s least significant difference test for normally distributed variables. Data are shown as scatter/dot plots with means ± SEM; n = 11. BLF low-frequency power of blood pressure variability, TP total power of heart rate variability, HF high-frequency power of heart rate variability, LF% normalized low-frequency power of heart rate variability, ln natural logarithm, nu normalized units

Effects of low temperature on baroreflex sensitivity during different sleep–wake stages

In a comparison of the three ambient temperatures in baroreflex sensitivity, BrrA and BrrD were lower at the lower ambient temperatures of 18 and 15 °C and even lower at 15 °C than at 18 °C without sleep staging and during AW and PS (Fig. 4A). Regarding the changes in BrrA and BrrD induced by 18 and 15 °C, both ambient temperatures induced prominent changes across all sleep–wake stages except the change induced by 18 °C in BrrA during AW, and the changes induced by 15 °C in both BrrA and BrrD were much greater than that induced by 18 °C mainly during AW and PS. Moreover, in comparison with the changes during AW, the 18 °C-induced changes in BrrA and BrrD were possibly increased during QS (BrrA, p = 0.051; BrrD, p = 0.070) and significantly increased during PS. Additionally, 15 °C induced more changes in BrrA and BrrD during the QS and PS stages than during the AW stage (Fig. 4B).

A Effects of different ambient temperatures (23, 18, and 15 °C) on baroreflex sensitivity indices of 24-h recordings without sleep scoring (Mix) and with distinctions among active waking (AW), quiet sleep (QS), and paradoxical sleep (PS) in rats. *p < 0.05 vs 23 °C, †p < 0.05 vs 18 °C by Fisher’s least significant difference test following a significant one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA); *p < 0.05 vs 23 °C, †p < 0.05 vs 18 °C by Dunn’s post hoc method following a significant Friedman’s test. B The changes in baroreflex sensitivity indices from 23 to 18 °C (18–23 °C) and from 23 to 15 °C (15–23 °C) during the AW, QS, and PS stages. All variables were normally distributed. *p < 0.05 vs 0 by one-sample t-test; †p < 0.05 vs 18–23 °C by paired t-test; #p < 0.05 vs AW by Fisher’s least significant difference test. Data are shown as scatter/dot plots with means ± SEM; n = 11. BrrA baroreflex sensitivity of ascending mean arterial pressure-R-R interval pairs, BrrD baroreflex sensitivity of descending mean arterial pressure-R-R interval pairs

Effects of low temperature on rat sleep patterns

There was no significant difference among the three ambient temperatures in terms of stage number or stage duration. However, the rats spent less cumulative time in QS and PS at lower ambient temperatures. In addition, they had more interruptions and a lower delta power percentage (an indicator of sleep depth) in QS specifically at 15 °C (Fig. 5).

A Effects of different ambient temperatures (23, 18, and 15 °C) on number, average duration, and cumulative time of 24-h recording with distinctions among active waking (AW), quiet sleep (QS), and paradoxical sleep (PS) and B interruption and delta power percentage of QS in rats. Data are shown as scatter/dot plots with means ± SEM; n = 11. *p < 0.05 vs 23 °C by Fisher’s least significant difference test following a significant one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA); *p < 0.05 vs 23 °C by Dunn’s post hoc method following a significant Friedman’s test; there was no significant difference between 18 and 15 °C by Fisher’s least significant difference test or Dunn’s post hoc method

Correlation between variations in MAP and cardiovascular response or sleep indices across the three ambient temperatures

We applied linear regression analysis to clarify the possible relationship between variations in mean 24-h MAP and the corresponding cardiovascular response or sleep pattern indices (Fig. 6) across the three ambient temperatures. The results showed that the variations in MAP induced by the three ambient temperatures were negatively correlated with the corresponding RR, TP, HF, BrrA, and BrrD and positively correlated with the corresponding BLF. However, no significant correlation was found between the variations in MAP and LF% (data not shown). In contrast, regarding the correlation of the variations in MAP with corresponding sleep patterns, MAP was positively correlated with interruption during QS and negatively correlated with delta power percentage during QS, but it was not correlated with cumulative time of QS.

A Two-dimensional scattergram and B the correlation coefficients displaying the relationship between the variations in mean arterial pressure (MAP) and the corresponding cardiovascular response measures without sleep scoring and sleep pattern variables during quiet sleep across three different ambient temperatures in rats. Data are shown as scatter/dot plots with means ± SEM; n = 11. *,*p < 0.05 vs 0 by one-sample t-test for normality and one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonnormality, respectively. RR R-R intervals, TP total power of heart rate variability, HF high-frequency power of heart rate variability, BLF low-frequency power of blood pressure variability, BrrA baroreflex sensitivity of ascending MAP-RR pairs, BrrD baroreflex sensitivity of descending MAP-RR pairs, ln natural logarithm, nu normalized units

Discussion

In the present study, cardiovascular autonomic function and sleep measurements were performed simultaneously at lower ambient temperatures in rats. We found that mild cold exposure increased BP, vascular sympathetic activity, and heart rate but reduced overall autonomic activity, parasympathetic activity, and baroreflex sensitivity. These phenomena were evident during both wakefulness and sleep. Moreover, mild cold exposure-induced changes in BP, heart rate, and baroreflex sensitivity were more prominent during sleep than during wakefulness. In addition, mild cold exposure led to sleep disturbance, which included decreased cumulative QS and PS time as well as increased interruptions and a decreased delta power percentage in QS. In a correlation analysis of BP and cardiovascular autonomic function, the results indicated that, in rats, mild cold-induced variations in BP had a positive correlation with corresponding vascular sympathetic activity and a negative correlation with corresponding RR, overall autonomic activity, parasympathetic activity, and baroreflex sensitivity, whereas in a correlation analysis of BP and sleep pattern, the mild cold-induced variations in BP had a negative correlation with corresponding delta power percentage during QS and a positive correlation with corresponding interruptions during QS.

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have connected cold-induced autonomic function, baroreflex, sleep, and BP changes in rats. This is also a pioneering study in that it explores the influences of the ambient temperature during winter in a subtropical location, such as Taiwan, which constitutes mild cold exposure. Previous studies using rodents have often compared the physiological and pathophysiological responses between animals housed at standard rodent facility temperatures (often 21–22 °C) and severely cold temperatures (typically 4–10 °C or even below 4 °C), which exposes rodents to extreme conditions that may greatly change their CBT [40] and not be physiologically relevant to humans [41, 42]. In the present study, we mainly explored the physiological responses in rats exposed to mild cold rats without affecting the mean 24-h CBT except for a slight increase during PS after sleep staging. Consistent with a previous study, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep was observed to be a poikilothermic state in which CBT was more influenced by ambient temperature than during wakefulness or non-REM sleep [43]. We chose 18 and 15 °C to mimic the ambient temperature during winter in Taiwan, which has averaged 16 °C over the last 3 years according to the Central Weather Bureau in Taiwan (2015–2018). Our results suggest that an ambient temperature of 18 °C results in a significant elevation in BP; increased vascular sympathetic activation; and decreased overall autonomic activity, parasympathetic activity, and baroreflex sensitivity as well as reduced QS time. Some of the aforementioned changes are more evident at 15 °C than at 18 °C. Notably, mild cold is able to rapidly increase BP and thereby disrupt BP control, in which cardiovascular autonomic regulation and sleep patterns play critical roles.

Much clinical literature has suggested that cold exposure activates the sympathetic nervous system, thereby elevating BP, leading to hypertension and cardiovascular disease [10]. Regarding the cold-induced changes in BP variability in the present study, the observed augmented vascular sympathetic activity is consistent with previous animal [18] and human [19] studies. Although the results of the aforementioned studies indicated that a low ambient temperature is linked mainly to increased BP and is mostly associated with increased vascular sympathetic activity, contradictory arguments can be offered as well. For example, higher nighttime BP occurs in summer than in winter [44], and vascular sympathetic activity did not change during a cold face test [22] but decreased during skin surface cooling without facial exposure [45]. Regarding the cold-induced changes in heart rate variability in the present study, heart rate increased and overall autonomic activity and parasympathetic activity decreased markedly, but cardiac sympathetic activity did not change except for its decrease during wakefulness. In line with the results of the present study, it has been reported that 3-day mild cold exposure at 20 °C relative to 30 °C induced increases in the heart rate of mice and decreases in their overall autonomic activity and parasympathetic activity [20]. Moreover, in wakeful human participants, acute exposure to severe cold resulted in decreased cardiac sympathetic activity [19]. In contrast to our results, cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic activity did not change during cold water immersion in either a human [26] or animal [18] study, but heart rate decreased, cardiac parasympathetic activity increased [19], and cardiac sympathetic activity during sleep decreased [28] during facial cooling without whole-body exposure among human participants. In addition, we observed that baroreflex sensitivity decreased during mild cold exposure in normotensive rats, which is consistent with observations in an animal model subjected to severe chronic cold air exposure at ~6 °C [21]. In contrast to our findings, baroreflex sensitivity did not change [27] or increase [19, 22, 46, 47] during acute cold air or water exposure among healthy human participants. The above findings imply that the seemingly contradictory findings probably relate to the variation in the type of exposure (duration, intensity, air vs water exposure, exposed parts of the body), varying study settings (posture, free-moving, or anesthetized states), and measurement (duration of physiological recording, direct vs indirect assessment), as well as individual characteristics (age). Moreover, in most previous studies, baroreflex sensitivity was evaluated through the injection of pressor or depressor agents [21, 27]. However, this procedure is potentially dangerous and may cause some stress in the participants. In contrast, we estimated baroreflex sensitivity from spontaneous fluctuations in heart rate and BP without artificially manipulating BP in this study. Furthermore, it is important to note that autonomic function is known to fluctuate in close parallel with the sleep–wake cycle; therefore, related studies might yield inconsistent findings depending on whether they discriminated sleep–wake states. However, the majority of related studies have explored the effects of acute cold exposure (often 5–20 min) on wakeful subjects or the effects of chronic cold exposure, but short-term physiological recordings were conducted mostly in the wakeful state. Relatively few studies have involved long-term continuous physiological recording during cold exposure and explored the influence of cold exposure during sleep [28]. Therefore, the precise physiological or pathological responses to cold exposure remain difficult to identify. In this study, we performed long-term, simultaneous, continuous recordings of sleep patterns and cardiovascular autonomic regulation during cold exposure for up to 24 h so that we could classify sleep–wake states in rats. We found that cold exposure may induce not only sleep pattern changes but also BP, heart rate, and cardiovascular autonomic control changes during each sleep–wake state. In particular, the magnitudes of the increase in BP and the decrease in heart rate and baroreflex sensitivity induced by cold exposure were much greater during sleep than during wakefulness. Notably, many studies have reported better prediction of cardiovascular risk from nighttime BP than from daytime BP [48, 49]. Therefore, the influences of cold exposure on cardiovascular responses during sleep are particularly noteworthy. Moreover, correlation analysis revealed that an elevation of BP in response to mild cold exposure may be a consequence of decreased overall autonomic activity, parasympathetic activity, and baroreflex sensitivity and increased vascular sympathetic activity.

Numerous human and animal studies have reported that cold exposure is associated with sleep problems, including difficulties initiating sleep [23], an increase in wakefulness, decreases in slow-wave sleep and REM sleep [24], and a decrease in sleep quality [25]. Few studies have found no effects of cold exposure on sleep patterns [28]. Our findings were consistent with the aforementioned results regarding the negative impact of cold exposure on sleep. The rats spent less time in QS and PS and had more interruptions in QS and a reduced depth of sleep at the lower ambient temperatures than at the control temperature. Moreover, in this study, a correlation analysis revealed that the decrease in sleep depth and increase in sleep interruptions in response to cold exposure may be the main sleep problems that increase BP.

In summary, on the basis of our findings, we postulate that intact vascular sympathetic activity, a cardiac autonomic nervous system with a parasympathetic predominance, baroreflex sensitivity, and good sleep quality are the most important factors in preventing cold exposure from disrupting BP. Moreover, mild cold exposure has the ability to convert individuals from a normotensive to a hypertensive state. This suggests that clinicians and individuals with either normotension or hypertension should be aware of these factors and pay close attention to BP levels during such exposures.

Several limitations might have affected the present study. First, cold-induced cardiovascular events are largely found in older patients with hypertension, and age-related changes were not explored in this study. In the future, we plan to use a hypertensive animal model to evaluate the effect of cold exposure on existing hypertension. Second, the sleep–wake behavior of rats is different between light and dark periods; rats spontaneously sleep for most of the light period and remain awake for most of the dark period. In this study, however, we explored the effects of cold exposure on 24-h physiological signals with discrimination of sleep stages but without classification of stages in the light–dark cycle. This is because we plan to explore another important topic, the effects of cold exposure on BP dips characterized by light period sleep-related declines in rat BP, as defined by our previous study [50]. Therefore, the changes in cardiovascular responses related to the light–dark cycle and a combination of the light–dark cycle and sleep–wake cycle will be further analyzed and presented in another study. Third, the seasonal variation in temperature and the variation in temperature across a single day may be among the factors influencing cardiovascular events; in this context, the present study investigated only static temperature effects. The effects of variable or dynamic temperature changes are worth investigating in the future. Fourth, only two lower temperature values (18 and 15 °C) were studied in this experiment. Although we did not explore the effects of much lower ambient temperatures on physiological function, we were concerned only with the effects of mild cold exposure on cardiovascular function and sleep in a range where CBT remains unaffected. Finally, although the autonomic nervous system is actively involved in regulating anabolic and catabolic processes, inputs from other hormones and neurotransmitters are also critical; therefore, future investigations should be aimed at identifying a direct link between the changes observed in this study and metabolic control.

Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that a mildly cold temperature may increase BP during all parts of the sleep–wake cycle, and the increase is especially pronounced during sleep stages. Additionally, mild cold exposure results in adverse impacts on not only autonomic function and baroreflex sensitivity but also the quantity and quality of sleep. Notably, these changes in response to cold temperature, including aggravated sympathovagal imbalance and sleep disturbances, may act as predictors of hypertension involved in more serious cold-induced cardiovascular events. Moreover, future research can focus on examining other influences, such as other cold exposure conditions or heat exposure, temperature dynamics across a single day, and humidity. These findings are expected to be useful for preventing and treating hypertension in addition to reducing the incidence of cardiovascular disease.

References

Wang H, Sekine M, Chen X, Kagamimori S. A study of weekly and seasonal variation of stroke onset. Int J Biometeorol. 2002;47:13–20.

Spencer FA, Goldberg RJ, Becker RC, Gore JM. Seasonal distribution of acute myocardial infarction in the second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1226–33.

Marchant B, Ranjadayalan K, Stevenson R, Wilkinson P, Timmis AD. Circadian and seasonal factors in the pathogenesis of acute myocardial infarction: the influence of environmental temperature. Br Heart J. 1993;69:385–7.

Brennan PJ, Greenberg G, Miall WE, Thompson SG. Seasonal variation in arterial blood pressure. Br Med J. 1982;285:919–23.

Minami J, Ishimitsu T, Kawano Y, Matsuoka H. Seasonal variations in office and home blood pressures in hypertensive patients treated with antihypertensive drugs. Blood Press Monit. 1998;3:101–6.

Winnicki M, Canali C, Accurso V, Dorigatti F, Giovinazzo P, Palatini P. Relation of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and short-term blood pressure variability to seasonal changes in environmental temperature in stage I hypertensive subjects. Results of the Harvest Trial. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1996;18:995–1012.

Sega R, Cesana G, Bombelli M, Grassi G, Stella ML, Zanchetti A, et al. Seasonal variations in home and ambulatory blood pressure in the PAMELA population. Pressione Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1585–92.

Kristal-Boneh E, Harari G, Green MS, Ribak J. Summer-winter variation in 24 h ambulatory blood pressure. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1:87–94.

Brook RD. The environment and blood pressure. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:213–21.

Lavados PM, Olavarria VV, Hoffmeister L. Ambient temperature and stroke risk: evidence supporting a short-term effect at a population level from acute environmental exposures. Stroke. 2018;49:255–61.

Joyner MJ, Charkoudian N, Wallin BG. A sympathetic view of the sympathetic nervous system and human blood pressure regulation. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:715–24.

La Rovere MT, Pinna GD, Raczak G. Baroreflex sensitivity: measurement and clinical implications. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2008;13:191–207.

Kiviniemi AM, Tulppo MP, Hautala AJ, Perkiomaki JS, Ylitalo A, Kesaniemi YA, et al. Prognostic significance of impaired baroreflex sensitivity assessed from Phase IV of the Valsalva maneuver in a population-based sample of middle-aged subjects. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:571–6.

Kuo TBJ, Yang CCH. Sleep-related changes in cardiovascular neural regulation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation. 2005;112:849–54.

Somers VK, Dyken ME, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Sympathetic-nerve activity during sleep in normal subjects. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:303–7.

Hirata T, Nakamura T, Kogure M, Tsuchiya N, Narita A, Miyagawa K, et al. Reduced sleep efficiency, measured using an objective device, was related to an increased prevalence of home hypertension in Japanese adults. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:23–9.

Stein PK, Pu Y. Heart rate variability, sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:47–66.

Yang YN, Tsai HL, Lin YC, Liu YP, Tung CS. Role of vasopressin V1 antagonist in the action of vasopressin on the cooling-evoked hemodynamic perturbations of rats. Neuropeptides. 2019;76:101939.

Hintsala HE, Kiviniemi AM, Tulppo MP, Helakari H, Rintamaki H, Mantysaari M, et al. Hypertension does not alter the increase in cardiac baroreflex sensitivity caused by moderate cold exposure. Front Physiol. 2016;7:204.

Axsom JE, Nanavati AP, Rutishauser CA, Bonin JE, Moen JM, Lakatta EG. Acclimation to a thermoneutral environment abolishes age-associated alterations in heart rate and heart rate variability in conscious, unrestrained mice. Geroscience. 2020;42:217–32.

Papanek PE, Wood CE, Fregly MJ. Role of the sympathetic nervous system in cold-induced hypertension in rats. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:300–6.

Stemper B, Hilz MJ, Rauhut U, Neundorfer B. Evaluation of cold face test bradycardia by means of spectral analysis. Clin Auton Res. 2002;12:78–83.

Krauchi K, Gasio PF, Vollenweider S, Von Arb M, Dubler B, Orgul S, et al. Cold extremities and difficulties initiating sleep: evidence of co-morbidity from a random sample of a Swiss urban population. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:420–6.

Okamoto-Mizuno K, Mizuno K. Effects of thermal environment on sleep and circadian rhythm. J Physiol Anthropol. 2012;31:14.

Cerri M, Ocampo-Garces A, Amici R, Baracchi F, Capitani P, Jones CA, et al. Cold exposure and sleep in the rat: effects on sleep architecture and the electroencephalogram. Sleep. 2005;28:694–705.

Xie L, Liu B, Wang X, Mei M, Li M, Yu X, et al. Effects of different stresses on cardiac autonomic control and cardiovascular coupling. J Appl Physiol. 2017;122:435–45.

Cui J, Durand S, Crandall CG. Baroreflex control of muscle sympathetic nerve activity during skin surface cooling. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1284–9.

Okamoto-Mizuno K, Tsuzuki K, Mizuno K, Ohshiro Y. Effects of low ambient temperature on heart rate variability during sleep in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;105:191–7.

Lin YK, Ho TJ, Wang YC. Mortality risk associated with temperature and prolonged temperature extremes in elderly populations in Taiwan. Environ Res. 2011;111:1156–63.

Kuo TBJ, Shaw FZ, Lai CJ, Yang CCH. Asymmetry in sympathetic and vagal activities during sleep-wake transitions. Sleep. 2008;31:311–20.

Li JY, Kuo TBJ, Yen JC, Tsai SC, Yang CCH. Voluntary and involuntary running in the rat show different patterns of theta rhythm, physical activity, and heart rate. J Neurophysiol. 2014;111:2061–70.

Kuo TBJ, Shaw FZ, Lai CJ, Lai CW, Yang CCH. Changes in sleep patterns in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Sleep. 2004;27:406–12.

Bjorvatn B, Fagerland S, Ursin R. EEG power densities (0.5-20 Hz) in different sleep-wake stages in rats. Physiol Behav. 1998;63:413–7.

Heart Rate Variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur heart J. 1996;17:354–81.

Kuo TBJ, Yien HW, Hseu SS, Yang CC, Lin YY, Lee LC, et al. Diminished vasomotor component of systemic arterial pressure signals and baroreflex in brain death. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(3 Pt 2):H1291–8.

Bertinieri G, Di Rienzo M, Cavallazzi A, Ferrari AU, Pedotti A, Mancia G. Evaluation of baroreceptor reflex by blood pressure monitoring in unanesthetized cats. Am J Physiol. 1988;254(2 Pt 2):H377–83.

Fritsch JM, Eckberg DL, Graves LD, Wallin BG. Arterial pressure ramps provoke linear increases of heart period in humans. Am J Physiol. 1986;251(6 Pt 2):R1086–90.

Munakata M, Imai Y, Takagi H, Nakao M, Yamamoto M, Abe K. Altered frequency-dependent characteristics of the cardiac baroreflex in essential hypertension. J Autonomic Nerv Syst. 1994;49:33–45.

Kuo TBJ, Lin T, Yang CCH, Li CL, Chen CF, Chou P. Effect of aging on gender differences in neural control of heart rate. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(6 Pt 2):H2233–9.

Wang YC, Kuo JS, Lin SZ. The effect of sphenopalatine postganglionic neurotomy on the alteration of local cerebral blood flow of normotensive and hypertensive rats in acute cold stress. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China B. 1998;22:122–8.

Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Nonshivering thermogenesis and its adequate measurement in metabolic studies. J Exp Biol. 2011;214(Pt 2):242–53.

Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Hung CM, Guertin DA. Emerging complexities in adipocyte origins and identity. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:313–26.

Szymusiak R. Body temperature and sleep. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;156:341–51.

Fedecostante M, Barbatelli P, Guerra F, Espinosa E, Dessi-Fulgheri P, Sarzani R. Summer does not always mean lower: seasonality of 24 h, daytime, and night-time blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1392–8.

Yamazaki F, Sone R. Thermal stress modulates arterial pressure variability and arterial baroreflex response of heart rate during head-up tilt in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;84:350–7.

Mourot L, Bouhaddi M, Gandelin E, Cappelle S, Nguyen NU, Wolf JP, et al. Conditions of autonomic reciprocal interplay versus autonomic co-activation: effects on non-linear heart rate dynamics. Auton Neurosci. 2007;137:27–36.

Yamazaki F, Sone R. Modulation of arterial baroreflex control of heart rate by skin cooling and heating in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:393–400.

Staessen JA, Thijs L, Fagard R, O’Brien ET, Clement D, de Leeuw PW, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk using conventional vs ambulatory blood pressure in older patients with systolic hypertension. Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. JAMA. 1999;282:539–46.

Dolan E, Stanton A, Thijs L, Hinedi K, Atkins N, McClory S, et al. Superiority of ambulatory over clinic blood pressure measurement in predicting mortality: the Dublin outcome study. Hypertension. 2005;46:156–61.

Kuo TBJ, Chen CY, Wang YP, Lan YY, Mak KH, Lee GS, et al. The role of autonomic and baroreceptor reflex control in blood pressure dipping and nondipping in rats. J Hypertens. 2014;32:806–16.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by a grant (109BRC-B504) from the Brain Research Center, National Yang-Ming University, from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan; a grant (10601-62-012) from Taipei City Hospital; and grants (MOST 106-2314-B-010-025 and MOST 106-2627-E-010-001) from the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan. The authors received no financial support from any manufacturer. Moreover, the authors thank Ms. Pei-Chi Hsu and Mr. Chen-Wei Huang for their article production support. The authors take full responsibility for the experimental design and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, CW., Wu, CH., Liou, YS. et al. Roles of cardiovascular autonomic regulation and sleep patterns in high blood pressure induced by mild cold exposure in rats. Hypertens Res 44, 662–673 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00619-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00619-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Short-term effects of exposure to cold spells on blood pressure among adults in Nanjing, China

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2024)

-

Reduced slow-wave activity and autonomic dysfunction during sleep precede cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Update on Hypertension Research in 2021

Hypertension Research (2022)