Abstract

Circadian fluctuation disorder of the intrarenal renin–angiotensin system (RAS) causes that of blood pressure (BP) and renal damage. In renal damage with an impaired glomerular filtration barrier, liver-derived angiotensinogen (AGT) filtered through damaged glomeruli regulates intrarenal RAS activity. Furthermore, glomerular permeability is more strongly affected by glomerular hypertension than by systemic hypertension. Thus, we aimed to clarify whether the circadian rhythm of intrarenal RAS activity is influenced by AGT filtered through damaged glomeruli due to glomerular capillary pressure. Rats with adriamycin nephropathy and an impaired glomerular filtration barrier were compared with control rats. In adriamycin nephropathy rats, olmesartan medoxomil (an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker) or hydralazine (a vasodilator) was administered, and the levels of intrarenal RAS components in the active and rest phases were evaluated. Moreover, the diameter ratio of afferent to efferent arterioles (A/E ratio), an indicator of glomerular capillary pressure, and the glomerular sieving coefficient (GSC) based on multiphoton microscopy in vivo imaging, which reflects glomerular permeability, were determined. Mild renal dysfunction was induced, and the systemic BP increased, resulting in increased A/E ratios in the adriamycin nephropathy rats compared with the control rats. Fluctuations in intrarenal RAS activity occurred in parallel with circadian fluctuations in glomerular capillary pressure, which disappeared with olmesartan treatment and were maintained with hydralazine treatment. Furthermore, the GSCs for AGT also showed similar changes. In conclusion, intrarenal RAS activity is influenced by the filtration of liver-derived AGT from damaged glomeruli due to circadian fluctuation disorder of the glomerular capillary pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mechanisms of intrarenal renin–angiotensin system (RAS) activation depend on the conditions of the glomerular filtration barrier. In renal conditions where the glomerular capillary wall is intact without proteinuria, angiotensin II (AngII) is filtered into the renal tubules because of its small molecular size and subsequently activates the intrarenal RAS [1]. In contrast, in kidneys with severe proteinuria due to an impaired glomerular filtration barrier, liver-derived angiotensinogen (AGT), not AngII, which is filtered through the damaged glomeruli, regulates intrarenal RAS activity [2].

Circulating RAS is known to have a circadian rhythm [3,4,5]. Previous studies revealed that intrarenal RAS activity also has a circadian rhythm and is correlated with circadian rhythm disorder of blood pressure (BP) and urinary protein [6,7,8,9]. However, the mechanism by which the circadian rhythm of intrarenal RAS activity occurs has not been elucidated. Several studies have reported no significant variation in circadian rhythms in liver AGT and plasma AGT [7, 10]. Glomerular permeability is augmented by glomerular injury [11, 12] and is more strongly affected by glomerular hypertension than by systemic hypertension [13]. Thus, circadian fluctuations in intrarenal AGT may be influenced by circadian fluctuations in glomerular permeability due to glomerular hypertension [8].

Multiphoton microscopy, which enables real-time visualization, is useful in analyzing the pathophysiology of the kidney [14]. To measure the glomerular capillary pressure and glomerular permeability, imaging of in vivo glomerular function by multiphoton microscopy has been developed [15,16,17].

This study aimed to visually clarify the mechanism of the circadian rhythm of intrarenal RAS activity with in vivo imaging using multiphoton microscopy. We focused on the filtration of AGT through the glomeruli depending on the glomerular capillary pressure.

Methods

Experimental design

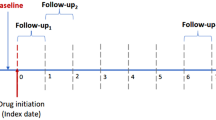

All animal procedures were conducted with the approval of the Animal Committee of the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine. Six-week-old male Wistar rats weighing 120–140 g were purchased from SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan) and kept under a 12:12-h light:dark cycle (lights on at 0700; zeitgeber time [ZT] 0).

The adriamycin nephropathy animal model is a well-established chronic kidney disease model. It is characterized by podocyte injury; as renal damage becomes more advanced, focal segmental and global glomerular sclerosis, tubulointerstitial inflammation, and fibrosis occur. As a result of histological damage, severe proteinuria, BP elevation, and renal dysfunction are induced depending on the dosage of adriamycin [18,19,20]. In this study, we focused on the influence of glomerular filtration of AGT due to glomerular capillary pressure, not histological damage, on intrarenal RAS activation, renal damage, hypertension, and circadian rhythms. Hence, we adopted a model with mild histological damage: 5-mg/kg adriamycin (Wako, Osaka, Japan) was administered through the tail veins of rats, and no remarkable histological differences were found between adriamycin nephropathy rats with and without treatment with RAS-dependent or RAS-independent antihypertensives.

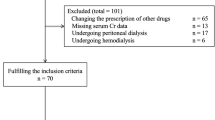

The rats were randomly assigned to the following four groups: group C (n = 32), the rats received 0.5 mL of 5% glucose instead of adriamycin on day 0 and were provided standard food and water; group A (n = 48), the rats received adriamycin on day 0 and were provided standard food and water; and group AO (n = 32) and group AH (n = 32), the rats were administered adriamycin on day 0, were provided standard food and water for the first 28 days, and then received 10 mg/kg per day olmesartan medoxomil (CS-866, Daiichi Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan), which was mixed with powdered food, or 5 mg/kg per day hydralazine hydrochloride (Wako, Osaka, Japan), which was added to the drinking water, to lower the BP to a value equivalent to that in group C, as previously described [21]. Sixteen animals in each group were euthanized by decapitation at ZT 6 or ZT 18 on day 56 after body weight (BW) measurement. Urine samples were collected using metabolic cages for 12 h, and BP was measured using a noninvasive tail-cuff method (BP 98A; Softron, Tokyo, Japan) before euthanasia. Blood samples and kidneys were collected immediately after decapitation. The remaining animals in all groups were subjected to experiments using multiphoton microscopy at ZT 6 or ZT 18 on day 56.

Evaluation of glomerular and tubulointerstitial lesions

Kidney tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson’s trichrome for the histopathological evaluation of glomerular and tubulointerstitial lesions.

Renal function and urinary protein excretion measurement

Serum and urinary creatinine (Cr) concentrations were measured by enzymatic assays (Sanritsu Zelkova Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan). Cr clearance (Ccr) was calculated as previously described [22]. Urinary protein excretion was measured using a pyrogallol red-molybdate protein assay kit (Wako), and urinary urea nitrogen excretion was measured using urease LED UV (SRL, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of circulating RAS concentrations and urinary AGT excretion levels

Plasma renin activity (PRA) and plasma AngII levels were measured using radioimmunoassay kits (SRL) to evaluate circulating RAS activity. In addition, the levels of urinary AGT as a surrogate marker for intrarenal RAS activity were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Cusabio, Houston, TX) with reference to previously reported methods [1, 23,24,25].

Measurement of intrarenal AngII concentrations

Samples of the renal cortex weighing 0.2–0.5 g were homogenized in 0.1-mol/L hydrochloric acid solution with a tenfold volume of tissue weight on ice. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min, and the supernatants were collected. AngII levels in the renal cortex were measured by SRL using a radioimmunoassay kit (Angiotensin II Set; Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan) and [125I] Tyr4-Angiotensin II (human) (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) with the florisil method. Intrarenal AngII concentrations were normalized against the weight of the resected kidney fragment, as previously described [26, 27].

Immunoblot and immunohistochemical analyses of intrarenal RAS components

To evaluate the circadian rhythm of intrarenal RAS components, an immunoblot analysis of AGT was conducted, as previously described [7, 21, 26, 28]. The primary antibodies used were a rabbit anti-AGT antibody (IBL, Takasaki, Japan) and a mouse anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (GAPDH; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX); the accumulation of these proteins, as determined by immunoblot analysis, was normalized against that of GAPDH.

Immunostaining for AGT in kidney sections was performed using a Histofine kit (Nichirei-Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan), as previously described [7, 26, 28]. The antibody used for immunoblot analysis was used for immunostaining (rabbit anti-AGT antibody). The immunoreactivity of AGT was quantitatively evaluated by a semiautomatic image analysis system using ImageJ software (version 1.52a, NIH, Bethesda, MD). Twenty microscopic fields were examined for each slide, and the average AGT-positive area excluding glomerular and vascular lesions was determined.

Fluorescent probes

A probe containing 500-kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) dextran (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was adjusted to 2 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and stored at −20 °C. Recombinant full-length human AGT (hAGT) was manufactured at IBL. Renin has high species specificity, and hAGT cannot be degraded by rat renin [1, 29]. Thus, hAGT was used to measure the glomerular permeability of liver-derived AGT. Moreover, hAGT was conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 maleimide (Alexa 488-hAGT; Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −20 °C until use.

Surgical procedures and in vivo imaging by multiphoton microscopy

Rats were placed on a heating plate and anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, and a catheter filled with 5% glucose as the vehicle to minimize the influence on the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism was inserted into the right jugular vein. The left kidney was exteriorized through a 10–15-mm incision [30]. Moreover, 1-mm cortical slices were removed to observe the glomeruli because the rats had no superficial glomeruli [15, 31,32,33]. Bleeding was minimal and ceased spontaneously within a few minutes.

An inverted multiphoton microscope (A1R MP+; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) that can measure fluorescence intensity with a 12-bit depth resolution was used for in vivo imaging. During intravital imaging, the rats were placed on a microscope stage with a heating function, and a rectal thermometer probe was inserted; the core body temperature was maintained between 36.5 and 37.5 °C. Moreover, 500-kDa FITC dextran (4 mg/kg) and Alexa 488-hAGT (0.3 mg/kg) were infused through a catheter inserted into the jugular vein. Observations were performed using a Nikon Plan Apo IR 60× (numerical aperture 1.27) water immersion objective. Images were acquired and analyzed using Nikon software (NIS-Elements, version 4.40).

Diameter ratio of afferent to efferent arterioles

The arteriole diameter was defined as the average value of the diameter from the glomerulus entrance to the distal 30 μm. As the afferent and efferent arteriole diameters depend on glomerular size, the diameter ratio of afferent to efferent arterioles (A/E ratio) was used as an indicator of glomerular capillary pressure [15, 34].

Measurement of the glomerular sieving coefficient (GSC)

The GSC for hAGT was defined as the ratio of the fluorescence intensity in Bowman’s capsule space to that in the glomerular capillaries. The GSC was measured based on a previously published method [1, 14, 15, 35,36,37,38]. Background images of the glomerular capillaries and Bowman’s capsule space were acquired at a depth of 20 μm from the surface. Five minutes after Alexa 488-hAGT injection, images of the glomerular capillaries and Bowman’s capsule space were obtained from the same site. Regions of interest (ROIs) included the areas in the glomerular capillaries with the highest fluorescence intensity and three different locations in Bowman’s capsule space, and the fluorescence intensity of each ROI was measured. Background correction values were generated by subtracting the corresponding background intensity from the fluorescence intensity of each ROI. Furthermore, the GSC was determined by dividing the average of the corrected Bowman’s capsule space fluorescence intensity by the corrected glomerular capillary fluorescence intensity. GSC measurements were performed in group A at ZT 18 and ZT 6 (n = 8 for both the active and rest phases). For each animal, three to four superficial glomeruli were selected.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SD. Significant differences among the groups were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for whole days or two-way ANOVA for circadian rhythms, followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Logarithmic transformation was used for urinary protein/creatinine (U-P/Cr) ratios to adjust for a normal distribution. A T-test was performed for GSC values. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 25 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Histopathological findings

Compared to group C, the other groups had remarkably enlarged glomerular sizes. Although some glomeruli showed segmental sclerosis, no significant changes in most glomeruli were found in groups A, AO, and AH. In addition, mild tubulointerstitial damage, such as tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, was observed in group A. No significant differences in tubulointerstitial damage were found in groups A, AO, and AH (Fig. 1).

Histopathological findings. Representative photomicrographs of the glomeruli and tubulointerstitium for all groups on day 56. The upper row shows periodic acid-Schiff staining (original magnification ×400). The lower row shows Masson’s trichrome staining (original magnification ×100). C control, A adriamycin, AO adriamycin + olmesartan, AH adriamycin + hydralazine

BW, BP, and renal damage

The BW in group C was higher than that in the adriamycin nephropathy groups. No significant differences in BW were found in the adriamycin nephropathy groups (Fig. 2a). Systolic BP (SBP) was significantly higher in group A than in group C. Olmesartan or hydralazine lowered the BP in groups AO and AH to the same level as that in group C (Fig. 2b). The Ccr was lower in group A than in group C. The Ccr in groups AO and AH was not significantly different from that in group A (Fig. 2c). The U-P/Cr ratios were significantly higher in group A than in group C and significantly improved in group AO; the U-P/Cr ratios in groups AH and A were not significantly different (Fig. 2d).

Body weight, blood pressure, and renal damage. a Body weight. b Systolic blood pressure (SBP). c Creatinine clearance (Ccr). d Urinary protein/creatinine ratio (U-P/Cr). Data represent the mean ± SD. #P < 0.05 vs. group C. †P < 0.05, group A vs. group AO. C control, A adriamycin, AO adriamycin + olmesartan, AH adriamycin + hydralazine

Circulating RAS and intrarenal RAS

The expression levels of intrarenal AGT protein, which is the only substrate in the intrarenal RAS, significantly increased in group A compared to group C based on immunoblot analysis and were decreased in group AO but not in group AH (Fig. 3a). Immunostaining for AGT in group C revealed slight expression in proximal tubular cells and dramatically increased expression in group A. Although intrarenal AGT expression was significantly reduced in group AO, that in group AH was not significantly decreased compared to that in group A (Fig. 3b). In addition, the levels of intrarenal AngII, which is an effector of the intrarenal RAS (Fig. 3c), and urinary AGT/Cr (U-AGT/Cr) ratios, which are surrogate markers for intrarenal RAS (Fig. 3d), significantly increased in group A compared to group C and decreased in group AO but not in group AH. The changes in the markers for intrarenal RAS activity were similar to those in U-P/Cr. Moreover, the levels of PRA and plasma AngII, which are markers of the circulating RAS, were significantly increased in the AO group compared to the other groups, and no significant differences among the other groups were observed (Fig. 3e, f).

Circulating renin–angiotensin system (RAS) and intrarenal RAS. a Immunoblot analysis of angiotensinogen (AGT) expression. Representative immunoblot data for AGT and densitometric ratios of AGT/glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Densitometric ratios of AGT bands to GAPDH bands were calculated. b Immunostaining for intrarenal AGT. Representative immunostaining for AGT at Zeitgeber time 18. Immunostaining for AGT in group C revealed weak expression in proximal tubular cells and dramatically increased expression in group A. Although intrarenal AGT expression was significantly reduced in group AO, that in group AH was not significantly decreased compared with that in group A. Original magnification ×400. The degree of immunoreactivity of AGT. The average immunoreactivity of AGT in 20 microscopic fields for each slide was quantitatively evaluated with a semiautomatic image analysis system using ImageJ. c Angiotensin II (AngII) concentrations in the renal cortex. d Urinary AGT/creatinine ratio (U-AGT/Cr). e Plasma renin activity (PRA). f Plasma AngII concentration. Data represent the mean ± SD. #P < 0.05 vs. group C. †P < 0.05, group A vs. group AO. C control, A adriamycin, AO adriamycin + olmesartan, AH adriamycin + hydralazine

Circadian rhythms of SBP, urinary protein excretion, and intrarenal RAS activation

The rats were awake from ZT 12 to 24 (active phase) and asleep from ZT 0 to 12 (rest phase) for a nocturnal active pattern. The SBP at ZT 18 was higher than that at ZT 6 in group C. The SBP at both ZT 18 and ZT 6 was higher in group A than in group C, and significant differences between the two phases were not observed. The SBP in groups AO and AH decreased to the same level as that in group C. Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, SBP tended to decrease more in the rest phase than in the active phase in group AO. However, no significant difference between the two phases was found in group AH (Fig. 4a). In addition, no significant differences in U-P/Cr and U-AGT/Cr parameters were found between the two phases in group C. By contrast, such parameters were higher in groups A and AH than in group C, and those in the active phases were higher than those in the rest phase in groups A and AH. U-P/Cr and U-AGT/Cr significantly decreased in group AO compared to group A; however, no significant difference between the two phases in group AO was noted (Fig. 4b, f). The variations in the circadian rhythms of intrarenal AGT protein expression levels were similar to those of U-P/Cr and U-AGT/Cr based on immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4c). The percentage of AGT-positive area and intrarenal AngII showed a trend similar to the levels of intrarenal AGT protein expression by immunoblot analysis and urinary AGT excretion (Fig. 4d, e).

Circadian rhythms of blood pressure, urinary protein excretion, and intrarenal renin–angiotensin system (RAS) activation. a Circadian fluctuation in systolic blood pressure (SBP). The solid line with open circles indicates group C; the solid line with closed circles, group A; the dashed line with closed squares, group AO; and the dotted line with closed triangles, group AH. b Circadian fluctuation in urinary protein/creatinine ratio (U-P/Cr). c Immunoblot analysis of angiotensinogen (AGT) expression and circadian fluctuation. Representative immunoblot data for AGT. Densitometric ratios of AGT/glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Densitometric ratios of AGT bands to GAPDH bands were calculated. Circadian fluctuation in d immunostaining for AGT, e angiotensin II (AngII) concentrations in the renal cortex, and f the urinary AGT/creatinine ratio (U-AGT/Cr). The active phase was defined as the period between zeitgeber time (ZT) 12 and ZT 24, and the rest phase was defined as the period between ZT 0 and ZT 12. The dark-colored bars on the left indicate the active phase or ZT 18; the light-colored bars on the right indicate the rest phase or ZT 6. Data represent the mean ± SD. #P < 0.05 vs. group C. †P < 0.05, group A vs. group AO. *P < 0.05, ZT 18 or active phase vs. ZT 6 or rest phase. C control, A adriamycin, AO adriamycin + olmesartan, AH adriamycin + hydralazine

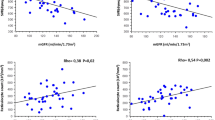

The A/E ratio and its circadian rhythm

We performed the experiment after the glomeruli were clearly observed (Supplementary Fig. 1). Afferent and efferent arterioles were examined (Fig. 5a). Figure 5b shows the arteriole diameters. In group C, the A/E ratios were not significantly different between ZT 18 and ZT 6. The A/E ratios in both ZT 18 and ZT 6 were significantly higher in group A than in group C. Moreover, the A/E ratios in ZT 18 were higher than those in ZT 6. The A/E ratios in group AO were remarkably higher than those in group C but were significantly lower than those in group A. Moreover, no significant differences were noted between ZT 18 and ZT 6. The A/E ratios did not decrease in group AH compared to group A, and a significant difference between ZT 18 and ZT 6 remained (Fig. 5c).

Data from in vivo imaging by multiphoton microscopy. a The glomeruli were visualized with a multiphoton microscope by perfusing 500-kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dextran. Representative image of the afferent (A) and efferent (E) arterioles. b The arteriole diameter was defined as the average value of the diameter from the glomerulus entrance to the distal 30 μm. c Circadian fluctuation in the diameter ratio of afferent to efferent arterioles (A/E ratio). The active phase was defined as the period between zeitgeber time (ZT) 12 and ZT 24; the rest phase was defined as the period between ZT 0 and ZT 12. The dark-colored dots on the left show ZT 18, and the light-colored dots on the right show ZT 6. d Representative image of the glomeruli and Bowman’s capsule space visualized with a multiphoton microscope by perfusing Alexa Fluor 488 maleimide-labeled human angiotensinogen (hAGT). e Circadian fluctuation in the glomerular sieving coefficient (GSC) for Alexa Fluor 488 maleimide-labeled hAGT in group A. The dark-colored dots on the left show ZT 18; the light-colored dots on the right show ZT 6. Data represent the mean ± SD. #P < 0.05 vs. group C. †P < 0.05, group A vs. group AO. *P < 0.05, ZT 18 vs. ZT 6. C control, A adriamycin, AO adriamycin + olmesartan, AH adriamycin + hydralazine, Bow Bowman’s capsule space, Cap glomerular capillaries

The GSC and its circadian rhythm

We performed the experiment after confirming glomerular filtration in adriamycin nephropathy rats. The fluorescence intensity of the glomeruli and Bowman’s capsule space was evaluated by infusing Alexa 488-hAGT (Fig. 5d). The GSCs for hAGT ranged from 0.0031 to 0.0035 at ZT 18 in group C under our experimental conditions. In group A, the GSCs for hAGT were 0.020 ± 0.0048 at ZT 18 and 0.018 ± 0.0042 at ZT 6 (p = 0.042) (Fig. 5e).

Discussion

Intrarenal RAS activity increased in adriamycin nephropathy rats, resulting in significant circadian fluctuations during the active phase. The glomerular capillary pressure and GSCs for hAGT measured by multiphoton microscopy showed variability similar to that of intrarenal RAS activity. These findings suggest that the circadian fluctuation in the intrarenal RAS was derived from AGT, which was filtered in response to glomerular capillary pressure in adriamycin nephropathy rats.

As previously reported, the circulating RAS and intrarenal RAS behave differently, and thus, their circadian fluctuations also differ [7, 39, 40]. Although the models were different, the tendency of circadian fluctuations of intrarenal RAS activity in the present study was consistent with our previous reports on rats treated with antithymocyte serum [7].

The circadian rhythm of the glomerular capillary pressure and GSC in the normal kidney has not been clarified [41]. Nonetheless, the glomerular capillary pressure in a normal kidney is maintained within a certain range by autoregulation, primarily through the myogenic response, tubuloglomerular feedback, and connecting tubule glomerular feedback [42,43,44]. Thus, it is expected that the circadian rhythm of the glomerular capillary pressure in the normal kidney is constant, as shown in this study. In a diseased kidney, autoregulation is impaired, and glomerular capillary pressure fluctuates under the influence of systemic BP, renal plasma flow, sympathetic nervous system, and several hormonal factors, including AngII [41, 44]. In our study, although no significant difference in SBP was found between ZT 18 and ZT 6 in group A, circadian fluctuation in A/E ratios occurred. Rats have most of their meals in the active phase during the day [45], and protein intake leads to renal vasodilation, with a corresponding increase in renal plasma flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [46,47,48]. This may be one of the reasons why the glomerular capillary pressure increased in the active phase compared to the rest phase, independent of the circadian rhythm of systemic BP. Furthermore, urinary urea nitrogen levels were measured as an indicator of protein intake, and we found that the levels were significantly higher in the active phase than in the rest phase in all groups (Supplementary Fig. 2), thereby indicating a higher protein intake in the active phase. When BP was reduced to the same degree by treatment with olmesartan or hydralazine, for the former, the A/E ratio decreased and circadian fluctuations disappeared, and for the latter, the A/E ratio did not significantly improve and circadian fluctuations were maintained. These results suggest that the glomerular capillary pressure in the diseased kidney was affected by not only systemic BP but also renal protective effects, such as autoregulation improvement through amelioration of endothelial dysfunction by AngII type 1 receptor blockers [49].

The value of measuring GSCs by multiphoton microscopy varies depending on the experimental conditions, such as the type of animal, body temperature, BP, body fluid volume, diet, fluorescent probe, and depth from the renal surface at which the fluorescence intensity is acquired [16, 17, 35]. Munich Wistar Frömter rats or Munich Wistar Simonsen rats are often used in multiphoton microscopy experiments because they have superficial glomeruli [1, 14, 16, 35,36,37,38]. However, we could not use these rats because of import restrictions; thus, we used Wistar rats. In our experiments, the GSCs for hAGT in group C were higher than those previously reported [1]; this could be attributed to the differences in animal species, fluorescent probes, imaging issues, and other experimental conditions. Therefore, in our study, it is more useful to compare differences between groups under the same conditions than to compare our results to absolute values in other reports [17], which does not have a significant effect on the conclusions of our experiment.

In addition, the GSC is inversely correlated with GFR [50]. The adriamycin nephropathy model has severe proteinuria without significant renal decline. Thus, the effect of GFR on the GSC is minimized in adriamycin nephropathy rats. Moreover, circadian fluctuations in GSC values occurred even though no significant differences in SBP were found between the active and rest phases in group A, which suggests that circadian fluctuations in AGT filtration occur in response to circadian fluctuations in glomerular capillary pressure instead of systemic BP.

According to our results, we consider that the mechanisms of BP, renal damage, intrarenal RAS activation, and their circadian fluctuation are as follows: mild renal damage was induced in adriamycin nephropathy rats, and the intrarenal RAS was activated. Consequently, the systemic BP and glomerular capillary pressure increased, which in turn increased the A/E ratio. High glomerular capillary pressure resulted in filtration of a large amount of AGT. However, we did not clarify whether the filtered AGT activated the intrarenal RAS and induced renal damage. Matsusaka et al. indicated that although AGT mRNA is expressed in the S3 segment of the proximal tubules in the kidney, AGT in the kidney does not induce substantial renal damage. In contrast, the liver-derived AGT that is filtered from the damaged glomeruli and absorbed by megalin in the S1 and S2 segments of the proximal tubules plays a pivotal role in the subsequent course [2, 51]. Adriamycin nephropathy rats showed intense AGT staining in S1–S3 segment proximal tubules in our immunohistochemical experiments (Supplementary Fig. 3). The distribution suggests that AGT in the kidney was derived from the liver. In the near future, we will perform experiments to confirm that liver-derived filtered AGT from damaged glomerular capillaries activates the intrarenal RAS and induces renal damage and that the fluctuation of filtered AGT is associated with BP, glomerular capillary pressure, and intrarenal RAS activation by using liver-specific AGT gene knockout mice.

This study has several limitations. First, the surface of the renal cortex was sliced in this study because the Wistar rats did not have superficial glomeruli. However, no obvious changes in image quality or fluorescent probe characteristics were found [31, 32]. Second, megalin-mediated endocytosis of hAGT in the proximal tubules was not evaluated. The use of multiphoton microscopy for quantitative analysis of proximal tubule protein uptake is not appropriate, and an evaluation method has not been established [17]. Nonetheless, this study showed that the circadian fluctuations in GSCs for hAGT and intrarenal RAS activity were similar, suggesting that filtered AGT from the glomeruli affects intrarenal RAS activity in adriamycin nephropathy rats. Third, circadian fluctuations in GSCs for hAGT were only evaluated for group A. The GFR differs even in glomeruli within the same individual. A reasonable number of glomeruli must be evaluated because GSC values vary. Thus, we assessed GSCs only in group A, where the difference between the active phase and the rest phase was considered to be the most important. However, the glomerular capillary pressure and GSCs for hAGT were correlated and were predicted to be similar in the other groups.

In conclusion, in adriamycin nephropathy rats, circadian fluctuations in BP, urinary protein, and intrarenal RAS activity were observed, which occurred in parallel with changes in glomerular capillary pressure and GSC for hAGT. Our results suggest that filtration of liver-derived AGT from the glomeruli due to circadian fluctuations in glomerular capillary pressure results in intrarenal RAS activity and that filtered AGT plays a pivotal role in BP elevation, intrarenal RAS activation, renal damage, and circadian fluctuations.

References

Nakano D, Kobori H, Burford JL, Gevorgyan H, Seidel S, Hitomi H, et al. Multiphoton imaging of the glomerular permeability of angiotensinogen. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1847–56.

Matsusaka T, Niimura F, Shimizu A, Pastan I, Saito A, Kobori H, et al. Liver angiotensinogen is the primary source of renal angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1181–9.

Gordon RD, Wolfe LK, Island DP, Liddle GW. A diurnal rhythm in plasma renin activity in man. J Clin Invest. 1966;45:1587–92.

Kala R, Fyhrquist F, Eisalo A. Diurnal variation of plasma angiotensin II in man. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1973;31:363–5.

Hilfenhaus M. Circadian rhythm of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the rat. Arch Toxicol. 1976;36:305–16.

Isobe S, Ohashi N, Fujikura T, Tsuji T, Sakao Y, Yasuda H, et al. Disturbed circadian rhythm of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: relevant to nocturnal hypertension and renal damage. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:231–9.

Isobe S, Ohashi N, Ishigaki S, Tsuji T, Sakao Y, Kato A, et al. Augmented circadian rhythm of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin systems in anti-thymocyte serum nephritis rats. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:312–20.

Ohashi N, Isobe S, Ishigaki S, Yasuda H. Circadian rhythm of blood pressure and the renin-angiotensin system in the kidney. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:413–22.

Ohashi N, Ishigaki S, Isobe S. The pivotal role of melatonin in ameliorating chronic kidney disease by suppression of the renin-angiotensin system in the kidney. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:761–8.

Nishijima Y, Kobori H, Kaifu K, Mizushige T, Hara T, Nishiyama A, et al. Circadian rhythm of plasma and urinary angiotensinogen in healthy volunteers and in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2014;15:505–8.

Olson JL, Hostetter TH, Rennke HG, Brenner BM, Venkatachalam MA. Altered glomerular permselectivity and progressive sclerosis following extreme ablation of renal mass. Kidney Int. 1982;22:112–26.

Anderson S, Meyer TW, Rennke HG, Brenner BM. Control of glomerular hypertension limits glomerular injury in rats with reduced renal mass. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:612–9.

Griffin KA, Picken MM, Bidani AK. Deleterious effects of calcium channel blockade on pressure transmission and glomerular injury in rat remnant kidneys. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:793–800.

Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA, Palygin O. Fluorescent imaging and microscopy for dynamic processes in rats. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;2018:151–75.

Satoh M, Kobayashi S, Kuwabara A, Tomita N, Sasaki T, Kashihara N. In vivo visualization of glomerular microcirculation and hyperfiltration in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Microcirculation. 2010;17:103–12.

Sandoval RM, Wagner MC, Patel M, Campos-Bilderback SB, Rhodes GJ, Wang E, et al. Multiple factors influence glomerular albumin permeability in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:447–57.

Nakano D, Nishiyama A. Multiphoton imaging of kidney pathophysiology. J Pharm Sci. 2016;132:1–5.

Okuda S, Oh Y, Tsuruda H, Onoyama K, Fujimi S, Fujishima M. Adriamycin-induced nephropathy as a model of chronic progressive glomerular disease. Kidney Int. 1986;29:502–10.

Lee VW, Harris DC. Adriamycin nephropathy: a model of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrology. 2011;16:30–8.

Hrenak J, Arendasova K, Rajkovicova R, Aziriova S, Repova K, Krajcirovicova K, et al. Protective effect of captopril, olmesartan, melatonin and compound 21 on doxorubicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Physiol Res. 2013;62 Suppl 1:S181–9.

Huang Y, Yamamoto T, Misaki T, Suzuki H, Togawa A, Ohashi N, et al. Enhanced intrarenal receptor-mediated prorenin activation in chronic progressive anti-thymocyte serum nephritis rats on high salt intake. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2012;303:F130–8.

Hosgood SA, Mohamed IH, Nicholson ML. The two layer method does not improve the preservation of porcine kidneys. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:BR27–33.

Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Urinary excretion of angiotensinogen reflects intrarenal angiotensinogen production. Kidney Int. 2002;61:579–85.

Yamamoto T, Nakagawa T, Suzuki H, Ohashi N, Fukasawa H, Fujigaki Y, et al. Urinary angiotensinogen as a marker of intrarenal angiotensin II activity associated with deterioration of renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1558–65.

Kobori H, Navar LG. Urinary angiotensinogen as a novel biomarker of intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in chronic kidney disease. Int Rev Thromb. 2011;6:108–16.

Ohashi N, Yamamoto T, Huang Y, Misaki T, Fukasawa H, Suzuki H, et al. Intrarenal RAS activity and urinary angiotensinogen excretion in anti-thymocyte serum nephritis rats. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2008;295:F1512–8.

Ohashi N, Isobe S, Ishigaki S, Suzuki T, Ono M, Fujikura T, et al. Intrarenal renin-angiotensin system activity is augmented after initiation of dialysis. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:364–70.

Ishigaki S, Ohashi N, Matsuyama T, Isobe S, Tsuji N, Iwakura T, et al. Melatonin ameliorates intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in a 5/6 nephrectomy rat model. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22:539–49.

Ganten D, Wagner J, Zeh K, Bader M, Michel JB, Paul M, et al. Species specificity of renin kinetics in transgenic rats harboring the human renin and angiotensinogen genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7806–10.

Molitoris BA, Sandoval RM. Intravital multiphoton microscopy of dynamic renal processes. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2005;288:F1084–9.

Rosivall L, Mirzahosseini S, Toma I, Sipos A, Peti-Peterdi J. Fluid flow in the juxtaglomerular interstitium visualized in vivo. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2006;291:F1241–7.

Rhodes GJ. Surgical preparation of rats and mice for intravital microscopic imaging of abdominal organs. Methods. 2017;128:129–38.

Kidokoro K, Cherney DZI, Bozovic A, Nagasu H, Satoh M, Kanda E, et al. Evaluation of glomerular hemodynamic function by Empagliflozin in diabetic mice using in vivo imaging. Circulation. 2019;140:303–15.

Monu SR, Ren Y, Masjoan-Juncos JX, Kutskill K, Wang H, Kumar N, et al. Connecting tubule glomerular feedback mediates tubuloglomerular feedback resetting after unilateral nephrectomy. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2018;315:F806–11.

Peti-Peterdi J. Independent two-photon measurements of albumin GSC give low values. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2009;296:F1255–7.

Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA. Quantifying glomerular permeability of fluorescent macromolecules using 2-photon microscopy in Munich Wistar rats. J Vis Exp. 2013. https://doi.org/10.3791/50052.

Schiessl IM, Castrop H. Angiotensin II AT2 receptor activation attenuates AT1 receptor-induced increases in the glomerular filtration of albumin: a multiphoton microscopy study. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2013;305:F1189–200.

Schiessl IM, Kattler V, Castrop H. In vivo visualization of the antialbuminuric effects of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2015;353:299–306.

Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharm Rev. 2007;59:251–87.

Navar LG, Harrison-Bernard LM, Nishiyama A, Kobori H. Regulation of intrarenal angiotensin II in hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:316–22.

Wuerzner G, Firsov D, Bonny O. Circadian glomerular function: from physiology to molecular and therapeutical aspects. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2014;29:1475–80.

Bidani AK, Griffin KA, Williamson G, Wang X, Loutzenhiser R. Protective importance of the myogenic response in the renal circulation. Hypertension. 2009;54:393–8.

Burke M, Pabbidi MR, Farley J, Roman RJ. Molecular mechanisms of renal blood flow autoregulation. Curr Vasc Pharm. 2014;12:845–58.

Carlstrom M, Wilcox CS, Arendshorst WJ. Renal autoregulation in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:405–511.

Su Y, Foppen E, Zhang Z, Fliers E, Kalsbeek A. Effects of 6-meals-a-day feeding and 6-meals-a-day feeding combined with adrenalectomy on daily gene expression rhythms in rat epididymal white adipose tissue. Genes Cells. 2016;21:6–24.

Lew SW, Bosch JP. Effect of diet on creatinine clearance and excretion in young and elderly healthy subjects and in patients with renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1991;2:856–65.

Bankir L, Roussel R, Bouby N. Protein- and diabetes-induced glomerular hyperfiltration: role of glucagon, vasopressin, and urea. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2015;309:F2–23.

Gabbai FB. The role of renal response to amino acid infusion and oral protein load in normal kidneys and kidney with acute and chronic disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2018;27:23–9.

Satoh M, Haruna Y, Fujimoto S, Sasaki T, Kashihara N. Telmisartan improves endothelial dysfunction and renal autoregulation in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:135–42.

Tanner GA. Glomerular sieving coefficient of serum albumin in the rat: a two-photon microscopy study. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2009;296:F1258–65.

Matsusaka T, Niimura F, Pastan I, Shintani A, Nishiyama A, Ichikawa I. Podocyte injury enhances filtration of liver-derived angiotensinogen and renal angiotensin II generation. Kidney Int. 2014;85:1068–77.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr Kengo Kidokoro (Kawasaki Medical School), Dr Daisuke Nakano (Kagawa University), Dr Chiharu Uchida (Hamamatsu University School of Medicine), and Dr Toshiyuki Ojima (Hamamatsu University School of Medicine) for critical technical support and important advice. We also acknowledge Daiichi Sankyo Co. (Tokyo, Japan) for providing olmesartan medoxomil (CS-866). This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (17K09693 to NO) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and by grants from the Young Investigator Research Projects of Hamamatsu University School of Medicine in 2018 (awarded to TM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matsuyama, T., Ohashi, N., Aoki, T. et al. Circadian rhythm of the intrarenal renin–angiotensin system is caused by glomerular filtration of liver-derived angiotensinogen depending on glomerular capillary pressure in adriamycin nephropathy rats. Hypertens Res 44, 618–627 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00620-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00620-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Sodium appetite is enhanced in 5/6 nephrectomized rat by high-sodium diet via increased levels of angiotensin II in the subfornical organ

Hypertension Research (2025)

-

Emerging topics on basic research in hypertension: interorgan communication and the need for interresearcher collaboration

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Update on Hypertension Research in 2021

Hypertension Research (2022)