Abstract

Baroreflex activation by electric stimulation of the carotid sinus (CS) effectively lowers blood pressure. However, the degree to which differences between stimulation protocols impinge on cardiovascular outcomes has not been defined. To address this, we examined the effects of short- and long-duration (SD and LD) CS stimulation on hemodynamic and vascular function in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs). We fit animals with miniature electrical stimulators coupled to electrodes positioned around the left CS nerve that delivered intermittent 5/25 s ON/OFF (SD) or 20/20 s ON/OFF (LD) square pulses (1 ms, 3 V, 30 Hz) continuously applied for 48 h in conscious animals. A sham-operated control group was also studied. We measured mean arterial pressure (MAP), systolic blood pressure variability (SBPV), heart rate (HR), and heart rate variability (HRV) for 60 min before stimulation, 24 h into the protocol, and 60 min after stimulation had stopped. SD stimulation reversibly lowered MAP and HR during stimulation. LD stimulation evoked a decrease in MAP that was sustained even after stimulation was stopped. Neither SD nor LD had any effect on SBPV or HRV when recorded after stimulation, indicating no adaptation in autonomic activity. Both the contractile response to phenylephrine and the relaxation response to acetylcholine were increased in mesenteric resistance vessels isolated from LD-stimulated rats only. In conclusion, the ability of baroreflex activation to modulate hemodynamics and induce lasting vascular adaptation is critically dependent on the electrical parameters and duration of CS stimulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Baroreflex activation therapy is a clinical tool designed to stimulate the carotid sinus (CS) to restore sympathovagal tone [1]. Multiple clinical trials have shown baroreflex activation therapy to be effective in decreasing blood pressure in treatment-resistant hypertensive patients [2,3,4,5,6] and improving outcomes in patients with heart failure [7, 8].

While the feasibility of baroreflex activation therapy in humans has been established, there may be considerable opportunity to improve its efficacy. For example, there is currently no set of standardized electrical stimulation parameters, and the reported stimulus frequencies, amplitudes, and durations have varied widely among human trials [4, 5, 9, 10]. While all of these trials reported positive outcomes, it is difficult to compare the efficacy of one stimulation protocol with that of another. Therefore, there is a strong need to define the importance of the relationship between the stimulation protocol and cardiovascular outcomes.

Dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system is one of the major underlying causes of hypertension in humans [11]. Baroreflex activation simultaneously decreases sympathetic activity and enhances parasympathetic activity, which together reduce blood pressure by promoting vasodilation and improve heart function by decreasing heart rate (HR) and left ventricular remodeling [12]. Importantly, continuous baroreflex activation produces a sustained decrease in sympathetic activity, blood pressure, and HR [13, 14]. The maintained depression of sympathetic activity and its attendant decrease in circulating norepinephrine contribute to the effects on blood pressure but do not fully account for them [15, 16]. Therefore, sustained baroreflex activation drives additional beneficial vascular adaptations by mechanisms yet to be defined [17].

Dysfunctional autonomic control of cardiovascular function is also present in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) and is associated with neurochemical changes in the central nervous system [18, 19], resulting in sympathetic overactivity [18], increased norepinephrine, and diminished baroreflex sensitivity, as observed in essential hypertensive patients [20,21,22,23], as well as structural and functional alterations in resistance vessel function contributing to the hypertensive process [24, 25]. Endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling are often associated with increased treatment-resistant hypertension [26]. Moreover, vascular dysfunction, comprising hypercontractility and decreased endothelial function, is present in both conductance and resistance arteries in experimental hypertension, as observed in SHRs [27] and hypertensive patients [28,29,30].

Heart rate variability (HRV) is decreased in SHRs compared with normotensive rats, indicating impaired autonomic regulation of the heart [31, 32]. HRV and systolic blood pressure variability (SBPV) analyses are widely used to assess autonomic nervous function [33, 34]. Specifically, the low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF) spectral components of HRV are used to indirectly study the sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation of the autonomic nervous system. HRV has emerged as a translational practical and noninvasive tool to quantitatively investigate cardiac autonomic dysregulation in humans [6, 35,36,37] and experimental conditions such as hypertension [38].

The goals of the current study were to determine the influence of baroreflex activation stimulation parameters on cardiovascular function and adaptive changes to the resistance vasculature in the SHR model. We hypothesized that different stimulation protocols would differentially affect metrics of cardiovascular function, namely, mean arterial pressure (MAP), SBPV, HR, and HRV. Since treatment-resistant hypertension is associated with endothelial dysfunction and increased reactivity of the resistance microvasculature [26, 29], we further hypothesized that baroreflex activation would improve endothelial function and decrease reactivity in resistance vessels.

Methods

Animals and surgical procedures

For all experiments, we used male 18- to 20-week-old SHRs supplied by the Animal Facility of the University of São Paulo, Campus of Ribeirão Preto. Animals were housed under controlled temperature (22 °C) conditions with a 12 h light/dark cycle and unrestricted access to tap water and standard rat chow, as previously described [39, 40]. All experimental procedures complied with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (NIH publication no. 85Y23, revised 1996) and were approved by the Committee on Animal Research and Ethics of Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo (Protocol No. 023/2013-1).

Rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). We then surgically implanted the CS electrodes together with a subcutaneous battery-operated pulse generator. A detailed description of electrode placement is described elsewhere [41]. Briefly, the CS was carefully isolated under a surgical microscope (DFVasconcelos, São Paulo, Brazil), and a bipolar stainless-steel electrode (0.008 inch bare, 0.011 inch Teflon coated; A-M Systems, Sequim, WA, USA) was placed around the left CS and CS nerve. Electrodes consisted of 2-mm-long hooks separated by 2 mm and insulated with silicone elastomer (Kwik-Sil; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). A miniaturized battery-operated electrical pulse generator was connected to the electrodes and implanted subcutaneously on the rat’s back. Finally, a polyethylene catheter was placed into the left femoral artery to record arterial pressure, as described previously [40]. As previously described in many of our studies using electric stimulation of the CS [41,42,43,44], 24 h is enough to restore cardiovascular function and baroreflex control after the ketamine–xylazine (KX) protocol [45,46,47]. Rats were separated into a sham-operated control group (n = 9) and two experimental groups, a short-duration (SD) stimulus (n = 9) and a long-duration (LD) stimulus (n = 8) group. Experimental procedures began 24 h after surgery.

Electrical stimulation of the CS

The baseline pulsatile arterial pressure (PAP) was recorded for 1 h before starting the electrical stimulus protocol. The electrical pulse generator was then remotely activated and delivered square pulses (3 V, 1 ms, 30 Hz) intermittently for the next 48 h. We chose an intermittent stimulus because continuous stimulation may disrupt the function of peripheral or central components of the baroreflex [48, 49]. One of two stimulation protocols was then applied: an LD (20 s ON and 20 s OFF) or an SD (5 s ON and 25 s OFF) protocol. A second 1-h PAP recording was acquired 24 h into the stimulation protocol and then again after stimulation was stopped at the 48-h time point. A schematic representation of the experimental procedure is shown in Fig. 1. All animals were carefully monitored for behavioral changes and stress during electrical stimulation. Signs or markers of distress [42, 43] (pain and electric shock signs) were observed in two animals, stimulation was stopped, and the animals were removed from the study. The experimental procedures did not cause any noticeable change in body weight or food and water intake. All experiments were carried out in conscious, freely moving rats housed in individual cages. Rats were taken to the recording room at least 60 min before the beginning of the experiment, and a quiet and noise-absent environment was maintained to avoid any stress. Moreover, we weighed animals for the anesthesia dosage, and no difference in body weight was found among groups over the following days.

Experimental methodology and carotid sinus stimulation parameters in spontaneously hypertensive rats. A: Heart rate (HR) and pulsatile arterial pressure (PAP) were monitored in conscious rats for 1 h before initiating a carotid sinus stimulation protocol (1° recording). A 48-h stimulation period was performed and a 1-h recording was aquired at the 24th h (2º recording). An additional 1 h of recording was captured after stimulation was stopped (3° recording). Animals were then euthanized, and mesenteric arteries were collected for ex vivo analysis. B: A schematic diagram (1 min) depicting the short duration (5 s ON and 25 s OFF) and long duration (20 s ON and 20 s OFF) square wave pulse (3 V, 1 ms, 30 Hz) CS stimulation protocols

Arterial pressure and HR measurements

The arterial catheter was connected to a pressure transducer (MLT0380/D, ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia), and the PAP was continuously sampled (2 kHz) by an IBM PC equipped with LabChart software. The MAP and HR were automatically calculated from the PAP using LabChart, as previously described [41, 43, 44].

HR and SBPV

The beat-to-beat time series of HR and systolic arterial pressure (SAP) were derived from 30-min recording windows of PAP using LabChart software’s blood pressure module. Power spectral analysis was used to assess HR and SAP variability in the frequency domain using CardioSeries software (available at http://www.danielpenteado.com). Values for HR and SAP were interpolated to 10 Hz (cubic spline interpolation) and divided into half-overlapping segments of 512 data points. A Hanning window was then applied to each segment, and the spectra were calculated by fast Fourier transform (FFT) and separated at low frequency (LF: 0.2–0.75 Hz) and high-frequency bins (HF: 0.75–3.0 Hz). Power spectra are shown in absolute (mmHg2) and normalized units (n.u.), as previously described [50,51,52]. In addition, HRV and SBPV in the time domain and spontaneous baroreflex assessment by the sequence method were also evaluated as previously described (Table 1) [53, 54].

Vascular function

After euthanasia, we isolated third-order mesenteric arterioles, mounted them in a small vessel wire myograph (Danish Myo Tech, Model 620M, A/S, Århus, Denmark), and set resting tension to 13.3 kPa. The arterioles were maintained in Krebs-Henseleit solution [KHS (in mmol/L) NaCl 130, KCl 4.7, KH2PO4 1.18, MgSO4 1.17, NaHCO3 14.9, glucose 5.5, EDTA 0.03, CaCl2 1.6] at 37 °C and gassed with a 95/5% O2/CO2 mix, and after a 30-min equilibration period, we assessed viability by monitoring the contractile response to high potassium (120 mmol/L). Experiments were carried out on vessels with either intact or mechanically denuded endothelium, the presence or absence of which was assessed by testing the vasodilatory response to acetylcholine (ACh, 10−5 mol/L) after precontraction with phenylephrine (PE, 10−6 mol/L). Experimental protocols involved precontraction with PE (10−6 to 3 × 10−6 mol/L) followed by either the cumulative addition of ACh (10−10 to 3 × 10−5 mol/L) in endothelium-intact vessels or the cumulative addition of sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 10−12 to 10−5 mol/L) in endothelium-denuded vessels, as well as the response to cumulative addition of PE (10−10 to 3 × 10−5 mol/L) in vessels with and without endothelium. Contractile responses were expressed as a percentage of KCl-induced contraction and vasodilation expressed as a percentage of relaxation relative to PE-induced precontraction. Cumulative concentration-response curves were fit using nonlinear regression, and the potency of agonists was expressed as pEC50 (negative logarithm of the EC50).

Analysis and statistics

Data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and all statistical analyses were carried out in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For the cardiovascular function measurements (MAP, HR, HRV, and SBPV), differences between means were assessed by repeated measures one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey analysis or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. For myography data, differences between pEC50 values were assessed by ANOVA. For all experiments, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

MAP and HR

We first assessed MAP and HR before, during, and after a 48-h application of either SD or LD CS stimulation (Fig. 1). In control animals, there was no difference in either the MAP or HR recorded at the same time intervals as the experimental groups (Fig. 2). Both the stimulated SD and LD showed significantly reduced MAP recorded during the stimulation period (Fig. 2, upper panel) compared to measurements recorded before stimulation (SD lowered MAP from 158 ± 4 to 130 ± 5 mmHg and LD from 173 ± 6 to 140 ± 5 mmHg). When recorded after the CS stimulation period had stopped, the MAP recovered to prestimulus levels after SD stimulation (before 158 ± 4 mmHg and after 148 ± 4 mmHg) but remained reduced after LD stimulation (before 173 ± 6 mmHg and after 150 ± 6 mmHg). In contrast to MAP, HR was only significantly reduced in stimulated SD, from 362 ± 11 bpm before CS stimulation to 328 ± 15 bpm during CS stimulation, and recovered to prestimulus levels after cessation (Fig. 2, lower panel).

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) before, during, and after short- or long-duration (SD or LD) carotid sinus (CS) stimulation. Upper and lower panels depict MAP and HR summary (mean ± SEM) and raw data points recorded before (open bars), during (gray bars), and after (open bars) short- and long-duration (SD, n = 9 and LD, n = 8) CS stimulation protocols, and in unstimulated sham-operated controls (n = 9), *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA)

HRV and SBPV

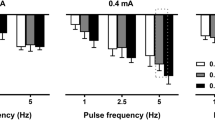

We next assessed HRV and SBPV in the time and frequency domains 1 h before and 48 h after SD or LD stimulation, and in the control group. There was no significant difference between before and after CS stimulation in standard deviation (SDNN) of blood pressure or pulse interval (PI) or in root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) of PI (Table 1). Additionally, there was no difference within the groups in either the LF and HF band measurements of the PI (Fig. 3A, B). Similarly, the LF band of the SBPV (Fig. 3C) was not significantly affected by either CS stimulation protocol. Thus, the reduced blood pressure seen after CS stimulation are unlikely to be caused by irreversible modulation of autonomic function.

Heart rate variability and systolic blood pressure variability before and after short- or long-duration (SD or LD) carotid sinus (CS) stimulation. A: Summary (mean ± SEM) of low frequency (LF) of the heart rate spectra before (gray bars) and after (white bars) (CS) stimulation in control, SD, and LD stimulation. B: Summary (mean ± SEM) and raw data points of high frequency (HF) spectra before (gray bars) and after (open bars) control, SD, and LD stimulation. C: Summary (mean ± SEM) and raw data points of low frequency (LF) of the blood pressure spectra before (gray bars) and after (open bars) control, SD, and LD stimulation. Control (n = 9), stimulated SD (n = 9), and LD (n = 8). No significant differences among groups (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test); n.u., normalized units

Mesenteric resistance arteriole function

While there was no difference in the maximum response to PE, the sensitivity of PE-induced contraction was increased after LD but not SD stimulation in both endothelium-intact and denuded arterioles (Fig. 4A, B). In endothelium-intact experiments, the mean ± SEM pEC50 for the LD group (5.7 ± 0.1, n = 4) was significantly higher (p < 0.01, ANOVA) than that of the control (5.4 ± 0.1, n = 7) and SD groups (5.4 ± 0.1, n = 9). Similarly, for endothelium-denuded arterioles, the pEC50 for the LD-stimulated group (5.9 ± 0.1, n = 7) was significantly higher (p < 0.01, ANOVA) than that of the control (5.6 ± 0.1, n = 6) and SD groups (5.2 ± 0.1, n = 6). We next evaluated relaxation induced by ACh in vessels precontracted with PE in endothelium-intact arterioles. Here, vessels from the LD group were more sensitive to ACh (8.9 ± 0.1, n = 5) than vessels from the control (8.3 ± 0.1, n = 7) or SD (8.4 ± 0.2, n = 5) groups (p < 0.05, ANOVA). Finally, in endothelium-denuded arteries, the degree of relaxation in response to the endothelium-independent vasodilator SNP was not different among the control, SD, and LD groups (Fig. 4D). Here, the mean ± SEM pEC50 values were 9.0 ± 0.2 (n = 6) for the control, 8.6 ± 0.2 (n = 5) for SD, and 9.2 ± 0.2 (n = 6) for LD. These data demonstrate that specific CS stimulation protocols, in this case LD stimulation, have the potential to affect lasting changes in vessel function.

Contractile properties of mesenteric resistance arterioles isolated from animals after short- or long-duration (SD or LD) carotid sinus stimulation. A, B: Contraction (mean ± SEM) expressed as a percentage of the maximal evoked by KCl in response to cumulative addition of phenylephrine (PE) in endothelium-intact (E+) vessels (black circles, control n = 7, gray squares, SD n = 9, open squares, LD n = 4) and denuded (E−) vessels isolated from the control (n = 6), SD (n = 6), and LD (n = 7) groups. C: Relaxation (mean ± SEM) endothelium-intact (E+) vessels (control n = 7, SD n = 5, LD n = 5) in response to cumulative addition of acetylcholine (ACh) after preconstriction with PE. D: Relaxation (mean ± SEM) endothelium-denuded (E−) vessels in response to cumulative addition of sodium nitroprusside (SNP) after preconstriction with PE (control n = 6, SD n = 5, and LD n = 6). For all experiments, differences between pEC50 values for groups were assessed by ANOVA (*p < 0.05)

Discussion

We hypothesized that different chronic CS stimulation protocols would differentially affect MAP, SBPV, HR, and HRV and further hypothesized that chronic CS stimulation would induce adaptive changes in the autonomic nervous system and resistance vasculature. By testing these hypotheses, we found that (1) decreases in HR and MAP measured during stimulation are dependent on CS stimulation, (2) decreases in MAP but not HR can be sustained for at least 1 h after stimulation is stopped, and (3) chronic CS stimulation can induce adaptive changes to resistance vasculature that are dependent on the CS stimulus protocol.

Chronic CS stimulation, defined as the delivery of continuous electrical pulses lasting longer than 1 h, robustly decreases MAP and HR in both rat and dog models [13, 41,42,43]. Human trials of the Rheos™ and Neo™ devices similarly employed continuous stimulus pulses [55, 56]. The goal of the current study was to determine the dependence of MAP and HR on the pulse protocol by investigating the effects of intermittent pulse trains of varying lengths (Fig. 1). We show that both SD and LD pulse protocols produce comparable changes in MAP when recorded during the stimulation period; however, only SD stimulation is able to significantly depress HR (Fig. 2). These differences demonstrate, for the first time, the influence of the parameters of CS stimulation on cardiovascular function. Such dependence might contribute to the lack of consistency between previously reported CS stimulation studies—although it should be emphasized that anatomical differences, electrode placement, pulse width, and voltage might also play a role. Nevertheless, our data provide a proof of principle that once electrodes are placed, the stimulation parameters can be fine-tuned to achieve a desired functional outcome.

Perhaps the most interesting and novel finding of the current study is that MAP, but not HR, remains depressed even after the cessation of LD but not SD stimulation (Fig. 2). CS stimulation depresses MAP and HR by modulating autonomic function and can be observed during CS stimulation by spectral analysis of AP and HR variability [57, 58]. However, it is not known whether chronic stimulation can induce a persistent change in autonomic function. To address this, we examined SBPV and HRV after the stimulation period had ended. Here, we found no difference in SBPV or HRV before or after the stimulation period (Fig. 3), indicating that the decrease in MAP observed after stopping stimulation is unlikely to be due to lasting modification of autonomic function. A limitation of the current study is that we only tracked MAP and HR for 1 h following the stimulation period, so further study is needed to define the persistence of MAP adaptations. Nevertheless, our findings support the justification for developing more intelligent feedback systems that monitor MAP and dynamically control the duration of stimulus and rest periods, with the goal of reducing side effects and prolonging device battery life [59].

We further explored the possibility that chronic CS stimulation induces lasting adaptations by evaluating the ex vivo function of resistance arterioles. Mesenteric vessels isolated from rats treated with LD and not SD stimulation protocols showed increased sensitivity to PE, which was not dependent on the presence of endothelium (Fig. 4A, B). Chronic CS stimulation produces a sustained decrease in sympathetic output [10, 13, 14]. This might be expected to promote an adaptive increase in vascular sensitivity to adrenergic stimulation. Indeed, previous studies have shown that adrenergic sensitivity is matched to sympathetic output, and decreased sympathetic activity results in increased sensitivity to adrenergic stimulation [60]. These adaptations are also seen after sympathetic denervation, where reduced sympathetic output leads to a compensatory increase in the expression of α1-adrenergic receptors [61, 62]. While our finding that CS stimulation promotes PE-induced vasoconstriction is consistent with the literature, it is counterintuitive since we would expect vasoconstriction to increase MAP but not decrease it. Interestingly, in vivo infusion of PE during CS stimulation in dogs had no effect on MAP, suggesting the presence of adaptations that oppose vasoconstriction [58].

In conclusion, we show that the cardiovascular effects of chronic CS stimulation are intriguingly dependent on electrical stimulation parameters. Importantly, the careful selection of parameters not only determines changes in HR evoked during CS stimulation but is critical for driving lasting adaptations in the resistance vasculature. These findings are significant because they provide a rationale for improving baroreflex activation therapy in humans.

References

Seravalle G, Dell’Oro R, Grassi G. Baroreflex activation therapy systems: current status and future prospects. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2019;16:1025–33.

Bisognano JD, Bakris G, Nadim MK, Sanchez L, Kroon AA, Schafer J, et al. Baroreflex activation therapy lowers blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled rheos pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:765–73.

Illig KA, Levy M, Sanchez L, Trachiotis GD, Shanley C, Irwin E, et al. An implantable carotid sinus stimulator for drug-resistant hypertension: surgical technique and short-term outcome from the multicenter phase II Rheos feasibility trial. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1213–8.

de Leeuw PW, Alnima T, Lovett E, Sica D, Bisognano J, Haller H, et al. Bilateral or unilateral stimulation for baroreflex activation therapy. Hypertension. 2015;65:187–92.

Tordoir JHM, Scheffers I, Schmidli J, Savolainen H, Liebeskind U, Hansky B, et al. An implantable carotid sinus baroreflex activating system: surgical technique and short-term outcome from a multi-center feasibility trial for the treatment of resistant hypertension. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:414–21.

Wustmann K, Kucera JP, Scheffers I, Mohaupt M, Kroon AA, de Leeuw PW, et al. Effects of chronic baroreceptor stimulation on the autonomic cardiovascular regulation in patients with drug-resistant arterial hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;54:530–6.

Abraham WT, Zile MR, Weaver FA, Butter C, Ducharme A, Halbach M, et al. Baroreflex activation therapy for the treatment of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:487–96.

Gronda E, Seravalle G, Brambilla G, Costantino G, Casini A, Alsheraei A, et al. Chronic baroreflex activation effects on sympathetic nerve traffic, baroreflex function, and cardiac haemodynamics in heart failure: a proof-of-concept study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:977–83.

Alnima T, Scheffers I, De Leeuw PW, Winkens B, Jongen-Vancraybex H, Tordoir JH, et al. Sustained acute voltage-dependent blood pressure decrease with prolonged carotid baroreflex activation in therapy-resistant hypertension. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1665–70.

Heusser K, Tank J, Engeli S, Diedrich A, Menne J, Eckert S, et al. Carotid baroreceptor stimulation, sympathetic activity, baroreflex function, and blood pressure in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2010;55:619–26.

Mancia G, Grassi G. The autonomic nervous system and hypertension. Circ Res. 2014;114:1804–14.

Yoruk A, Bisognano JD, Gassler JP. Baroreceptor stimulation for resistant hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:1319–24.

Lohmeier TE, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Serdar DJ, Kieval RS. Prolonged activation of the baroreflex produces sustained hypotension. Hypertension. 2004;43:306–11.

Lohmeier TE, Dwyer TM, Hildebrandt DA, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Serdar DJ, et al. Influence of prolonged baroreflex activation on arterial pressure in angiotensin hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:1194–1200.

Lohmeier TE, Hildebrandt DA, Dwyer TM, Iliescu R, Irwin ED, Cates AW, et al. Prolonged activation of the baroreflex decreases arterial pressure even during chronic adrenergic blockade. Hypertension. 2009;53:833–8.

Lohmeier TE, Hildebrandt DA, Dwyer TM, Barrett AM, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, et al. Renal denervation does not abolish sustained baroreflex-mediated reductions in arterial pressure. Hypertension. 2007;49:373–9.

Lohmeier TE, Iliescu R. Chronic lowering of blood pressure by carotid baroreflex activation: mechanisms and potential for hypertension therapy. Hypertension. 2011;57:880–6.

Judy WV, Watanabe AM, Murphy WR, Aprison BS, Yu PL. Sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in normotensive backcross rats genetically related to the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 1979;1:598–604.

Yamori Y, Okamoto K. Hypothalamic tonic regulation of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Jpn Circ J. 1969;33:509–19.

Courand P-Y, Feugier P, Workineh S, Harbaoui B, Bricca G, Lantelme P. Baroreceptor stimulation for resistant hypertension: first implantation in France and literature review. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;107:690–6.

Griffith LS, Schwartz SI. Reversal of renal hypertension by electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve. Surgery. 1964;56:232–9.

Lohmeier TE, Barrett AM, Irwin ED. Prolonged activation of the baroreflex: a viable approach for the treatment of hypertension? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2005;7:193–8.

Matsukawa T, Gotoh E, Hasegawa O, Shionoiri H, Tochikubo O, Ishii M. Reduced baroreflex changes in muscle sympathetic nerve activity during blood pressure elevation in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1991;9:537–42.

Schiffrin EL. Reactivity of small blood vessels in hypertension: relation with structural changes. State of the art lecture. Hypertension. 1992;19:II1–9.

Naito Y, Yoshida H, Konishi C, Ohara N. Differences in responses to norepinephrine and adenosine triphosphate in isolated, perfused mesenteric vascular beds between normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;32:807–18.

Versari D, Daghini E, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S. Endothelium-dependent contractions and endothelial dysfunction in human hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:527–36.

Luscher TF, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-dependent contractions to acetylcholine in the aorta of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 1986;8:344–8.

Linder L, Kiowski W, Buhler FR, Luscher TF. Indirect evidence for release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor in human forearm circulation in vivo. Blunted response in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1990;81:1762–7.

Taddei S, Virdis A, Mattei P, Salvetti A. Vasodilation to acetylcholine in primary and secondary forms of human hypertension. Hypertension. 1993;21:929–33.

Armario P, Oliveras A, Hernandez Del Rey R, Ruilope LM, De La Sierra A, Grupo de Investigadores del Registro de Hipertension refractaria de la Sociedad Espanola de Hipertension/Liga Espanola para la Lucha contra la Hipertension, Arterial. [Prevalence of target organ damage and metabolic abnormalities in resistant hypertension]. Med Clin. 2011;137:435–9.

Friberg P, Karlsson B, Nordlander M. Sympathetic and parasympathetic influence on blood pressure and heart rate variability in Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens Suppl. 1988;6:S58–60.

Ricksten SE, Lundin S, Thoren P. Spontaneous variations in arterial blood pressure, heart rate and sympathetic nerve activity in conscious normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1984;120:595–600.

Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzzetti S, Rimoldi O, Furlan R, Pizzinelli P, et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res. 1986;59:178–93.

Pomeranz B, Macaulay RJ, Caudill MA, Kutz I, Adam D, Gordon D, et al. Assessment of autonomic function in humans by heart rate spectral analysis. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:H151–3.

Liao D, Cai J, Barnes RW, Tyroler HA, Rautaharju P, Holme I, et al. Association of cardiac automatic function and the development of hypertension: the ARIC study. Am J Hypertens. 1996;9:1147–56.

Fagard RH, Pardaens K, Staessen JA. Relationships of heart rate and heart rate variability with conventional and ambulatory blood pressure in the population. J Hypertens. 2001;19:389–97.

Lucini D, Mela GS, Malliani A, Pagani M. Impairment in cardiac autonomic regulation preceding arterial hypertension in humans. Circulation. 2002;106:2673–9.

Silva LEV, Geraldini VR, de Oliveira BP, Silva CAA, Porta A, Fazan R. Comparison between spectral analysis and symbolic dynamics for heart rate variability analysis in the rat. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8428.

Margatho LO, Porcari CY, Macchione AF, da Silva Souza GD, Caeiro XE, Antunes-Rodrigues J, et al. Temporal dissociation between sodium depletion and sodium appetite appearance: involvement of inhibitory and stimulatory signals. Neuroscience. 2015;297:78–88.

Domingos-Souza G, Meschiari CA, Buzelle SL, Callera JC, Antunes-Rodrigues J. Sodium and water intake are not affected by GABAC receptor activation in the lateral parabrachial nucleus of sodium-depleted rats. J Chem Neuroanat. 2016;74:47–54.

Katayama PL, Castania JA, Dias DP, Patel KP, Fazan R Jr, Salgado HC. Role of chemoreceptor activation in hemodynamic responses to electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus in conscious rats. Hypertension. 2015;66:598–603.

Domingos-Souza G, Santos-Almeida FM, Meschiari CA, Ferreira NS, Pereira CA, Martinez D, et al. Electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus lowers arterial pressure and improves heart rate variability in L-NAME hypertensive conscious rats. Hypertens Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0448-7.

Santos-Almeida FM, Domingos-Souza G, Meschiari CA, Favaro LC, Becari C, Castania JA, et al. Carotid sinus nerve electrical stimulation in conscious rats attenuates systemic inflammation via chemoreceptor activation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6265.

Domingos-Souza GS, Santos-Almeida FM, Silva LE, Dias D, Silva CA, Castania JA, et al. Electrical stimulation of carotid sinus in conscious normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. FASEB J. 2015;29. https://faseb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1096/fasebj.29.1_supplement.648.10.

Tremoleda JL, Kerton A, Gsell W. Anaesthesia and physiological monitoring during in vivo imaging of laboratory rodents: considerations on experimental outcomes and animal welfare. EJNMMI Res. 2012;2:44.

Albrecht M, Henke J, Tacke S, Markert M, Guth B. Effects of isoflurane, ketamine-xylazine and a combination of medetomidine, midazolam and fentanyl on physiological variables continuously measured by telemetry in Wistar rats. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-014-0198-3.

Janssen BJA, De Celle T, Debets JJM, Brouns AE, Callahan MF, Smith TL. Effects of anesthetics on systemic hemodynamics in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1618–24.

Heusser K, Tank J, Luft FC, Jordan J. Baroreflex failure. Hypertension. 2005;45:834–9.

Robertson D, Hollister AS, Biaggioni I, Netterville JL, Mosqueda-Garcia R, Robertson RM. The diagnosis and treatment of baroreflex failure. N. Engl J Med. 1993;329:1449–55.

van de Borne P, Montano N, Pagani M, Oren R, Somers VK. Absence of low-frequency variability of sympathetic nerve activity in severe heart failure. Circulation. 1997;95:1449–54.

Montano N, Ruscone TG, Porta A, Lombardi F, Pagani M, Malliani A. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability to assess the changes in sympathovagal balance during graded orthostatic tilt. Circulation. 1994;90:1826–31.

Billman GE. Heart rate variability - a historical perspective. Front Physiol. 2011;2:86.

Duque JJ, Silva LE, Murta LO. Open architecture software platform for biomedical signal analysis. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2013;2013:2084–7.

Di Rienzo M, Parati G, Castiglioni P, Tordi R, Mancia G, Pedotti A. Baroreflex effectiveness index: an additional measure of baroreflex control of heart rate in daily life. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R744–51.

Scheffers IJ, Kroon AA, Schmidli J, Jordan J, Tordoir JJ, Mohaupt MG, et al. Novel baroreflex activation therapy in resistant hypertension: results of a European multi-center feasibility study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1254–8.

Wallbach M, Lehnig L-Y, Schroer C, Lüders S, Böhning E, Müller GA, et al. Effects of baroreflex activation therapy on ambulatory blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;67:701–9.

Iliescu R, Tudorancea I, Lohmeier TE. Baroreflex activation: from mechanisms to therapy for cardiovascular disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16:453.

Lohmeier TE, Iliescu R, Dwyer TM, Irwin ED, Cates AW, Rossing MA. Sustained suppression of sympathetic activity and arterial pressure during chronic activation of the carotid baroreflex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H402–9.

Tohyama T, Hosokawa K, Saku K, Oga Y, Tsutsui H, Sunagawa K. Smart baroreceptor activation therapy strikingly attenuates blood pressure variability in hypertensive rats with impaired baroreceptor. Hypertension. 2020;75:885–92.

Charkoudian N, Joyner MJ, Sokolnicki LA, Johnson CP, Eisenach JH, Dietz NM, et al. Vascular adrenergic responsiveness is inversely related to tonic activity of sympathetic vasoconstrictor nerves in humans. J Physiol. 2006;572:821–7.

Yeoh M, McLachlan EM, Brock JA. Tail arteries from chronically spinalized rats have potentiated responses to nerve stimulation in vitro. J Physiol. 2004;556:545–55.

Lee J-S, Fang S-Y, Roan J-N, Jou I-M, Lam C-F. Spinal cord injury enhances arterial expression and reactivity of α1-adrenergic receptors-mechanistic investigation into autonomic dysreflexia. Spine J. 2016;16:65–71.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Brazilian public funding from the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP). We also thank Dr. Helio Cesar Salgado for the use of his laboratory and scientific support and Dr. Daniel Penteado Martins Dias, Dr. Luiz Eduardo Virgílio Silva, and Jaci Airton Castania for expert technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Domingos-Souza, G., Santos-Almeida, F.M., Meschiari, C.A. et al. The ability of baroreflex activation to improve blood pressure and resistance vessel function in spontaneously hypertensive rats is dependent on stimulation parameters. Hypertens Res 44, 932–940 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00639-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00639-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Key challenges in exploring the rat as a preclinical neurostimulation model for aortic baroreflex modulation in hypertension

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

Advances on the Experimental Research in Resistant Hypertension

Current Hypertension Reports (2024)

-

Emerging topics on basic research in hypertension: interorgan communication and the need for interresearcher collaboration

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Differential frequency-dependent reflex summation of the aortic baroreceptor afferent input

Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology (2023)

-

Low intensity stimulation of aortic baroreceptor afferent fibers as a potential therapeutic alternative for hypertension treatment

Scientific Reports (2022)