Abstract

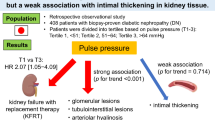

Although central hemodynamics are known to be closely associated with microvascular damage, their association with lesions in the small renal arteries has not yet been fully clarified. We focused on arterioles in renal biopsy specimens and analyzed whether their structural changes were associated with noninvasive vascular function parameters, including central blood pressure (BP) and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV). Forty-four nondiabetic patients (18–50 years of age) with preserved renal function underwent renal biopsy. Wall thickening of arterioles was analyzed based on the media/diameter ratio, and hyalinosis was analyzed by semiquantitative grading. Associations of these indexes (arteriolar wall remodeling grade index (RG index) and arteriolar hyalinosis index (Hyl index)) with clinical variables were analyzed. Multiple regression analyses demonstrated that the RG index was significantly associated with central systolic BP (β = 0.97, p = 0.009), serum cystatin C-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (β = −0.36, p = 0.04), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (β = −0.37, p = 0.02). The Hyl index was significantly associated with baPWV (β = 0.75, p = 0.01). Our results indicate that aortic stiffness and abnormal central hemodynamics are closely associated with renal microvascular damage in young to middle-aged, nondiabetic kidney disease patients with preserved renal function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small arteries in the kidney maintain a low level of impedance to allow for continuous blood flow from the aorta, whereas they act protectively toward the periphery by resisting excessive blood flow and pressure from the central blood vessels associated with their contraction [1]. However, small arteries are at risk of being damaged due to their exposure to high blood flow as well as their fragility. Fibrous intimal thickening in the small arteries and medial thickening [2,3,4] and hyalinosis in the arterioles [5, 6] have been reported to occur as a result of increased blood pressure (BP). Intrarenal small artery lesions have been suggested to be predictive of future renal function deterioration and exacerbation of proteinuria [7,8,9,10]. Furthermore, associations of these lesions with coronary and aortic sclerosis, major cerebrovascular disease, and disease prognosis have been observed [6, 9, 11, 12], which suggests their close association with systemic blood vessels.

Central arterial BP is the cardiac afterload itself and reflects vascular resistance, but central arterial BP is also indicative of the pressure applied to peripheral organs. Pulse wave velocity (PWV) indicates aortic sclerosis and can predict a decline in renal function as well as the progression of cardiovascular disease [1, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

To date, most studies investigating the association between these central vascular function parameters and small artery lesions have included older patients or patients with decreased renal function, and there are few studies that have included younger patients with preserved renal function. Therefore, in this study, we analyzed the association between the characteristics of small artery lesions in renal biopsy specimens, central vascular function parameters, and metabolic risk factors in younger patients with preserved renal function.

Methods

Study participants

A cross-sectional observational study was performed at our hospital from November 2015 to November 2019. A total of 192 patients underwent renal biopsy due to a diagnosis of renal disease or urine abnormality during this period. We consecutively enrolled patients aged 19–50 years whose serum creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFRcr) level was >60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Patients with diabetes mellitus, collagen disease, chronic liver disease, or acute renal injury were excluded. A total of 49 eligible patients agreed to participate in this study.

Patients with hypertension were defined as those with a brachial BP of 140/90 mmHg or higher or those taking antihypertensive drugs, and smokers included both past and present smokers. The duration of renal disease was calculated according to the day on which urinary abnormalities were detected at a hospital or a routine health checkup for the first time. Blood biochemical analyses, including the analysis of serum cystatin C levels, were performed on the day of admission. Fasting blood glucose and insulin levels were measured the morning after the biopsy. Serum creatinine was measured twice during hospitalization, and the average of the two measurements was used as a variable. The estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated by the formula established for Japanese subjects [21, 22] using age, sex, and serum creatinine or cystatin C and is shown as eGFRcr or cystatin C-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFRcysC), respectively.

Measurement of central BP, brachial BP, and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) was performed by a trained technician on the day after the biopsy. PWV was measured using a BP-203RPE from PWV/ABI (Fukuda Colin Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) with the patient in the supine position, and central BP and brachial BP were measured using an HEM-9000AI (Omron, Kyoto, Japan) with the patient in the sitting position after at least 5 min of rest. For PWV, the mean values of the bilateral arms and ankles were used as a variable.

The research protocol of this cross-sectional study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University Hospital (study approval number: SH3092). Potential participants were asked for their written informed consent at the time of admission, and those who provided consent to participate were enrolled in the study. Finally, five patients missing either central BP or baPWV data were excluded, and 44 patients were analyzed.

Histological analyses

For arteriole lesions, arteriole wall thickening and arteriole hyalinosis were evaluated semiquantitatively using periodic acid-Schiff staining (PAS). Only arterioles that were continuous with glomeruli or were predicted to have continuity with glomeruli, those with an outer diameter of <100 μm and those with one to three layers of smooth muscle were evaluated. Both afferent and efferent arterioles were evaluated to avoid confusing afferent arterioles and severely remodeled efferent arterioles. Arteriolar wall thickening was evaluated referring to the arteriolar media/lumen (M/L) ratio [3]. To evaluate M/L ratios easily, the thickness of the media relative to the outer diameter was evaluated visually [7, 23], as follows. Arterial wall thickening was categorized into four grades (from 0 to 3), i.e., grade 0 (G0): more than 0.6; grade 1 (G1): ≤0.6 and more than 0.5; grade 2 (G2): ≤0.5 and more than 0.2; and grade 3 (G3): ≤0.2 but not occluded (Fig. 1). Next, the remodeling grade (RG) index was calculated according to the average grade using the following equation, which was established previously [5, 24, 25]: arteriolar wall RG index = (n0 × 0 + n1 × 1 + n 2 × 2 + n3 × 3)/N. Here, n1–n3 represent the number of arterioles categorized as G1–G3, respectively, and N represents the total number of arterioles. For arteriolar hyalinosis, the following grading system based on the degree of hyalinosis of the arterial wall was used: G0: none; G1: hyalinosis of 50% or less of the wall; G2: hyalinosis occupying more than 50% of the wall but not the whole layer; and G3: hyalinosis occupying the whole layer. The average hyalinosis grade was calculated in the same way as the RG index, as follows: arteriolar hyalinosis index (Hyl index) = (n0 × 0 + n1 × 1 + n2 × 2 + n3 × 3)/N. The proportion of arterioles assessed as having an RG index of G2 or G3 (defined as arteriolar wall thickening) and the proportion of arterioles assessed as having a Hyl index of G1 or more relative to the total number of observed arterioles were also assessed in each patient. Global glomerulosclerosis was evaluated as a proportion of the total glomeruli using PAS (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

Representative microscopic findings of arteriolar wall remodeling (grades 0–3), arteriolar hyalinosis (grades 0–3), and PAS staining (×400). A Arteriolar remodeling was assessed using the arteriolar media-to-diameter ratio by semiquantitative grading. B Arteriolar hyalinosis grade was similarly assessed by semiquantitative grading

Intimal thickening of the arcuate artery and interlobar artery was determined by the ratio of the intima/media thickness using Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining or Elastica van Gieson staining. Intimal thickening was evaluated as a grade between 0 and 2: G0: no intimal thickening; G1: intimal/medial ratio < 1; and G2: intimal/medial ratio ≥ 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy (IF/TA) was evaluated by calculating the percentage of the relevant area to that of the whole cortex. The blue area on MT staining was defined as interstitial collagen, and IF/TA was scored on a scale of 0–3 as follows: G0: none; G1: <25%; G2: 25–50%; and G3: 50% or more (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Interstitial cell infiltration (InF) was evaluated by calculating the percentage of the area within the cortex that contains small round cells on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections and was scored on a four-point scale (from 0 to 3) as follows: G0: none; G1: localized interstitial InF; G2: multiple lesions of interstitial InF; and G3: diffuse interstitial InF (Supplementary Fig. 1d).

Arterioles were assessed by one physician (YM) blinded to the clinical information. This physician’s evaluation of randomly selected patients was confirmed to be the same as that of another physician (TO). The RG index and Hyl index were also confirmed to be associated with the results of a three-level semiquantitative evaluation by a pathologist (TN) blinded to the clinical information, and a moderate or higher correlation was confirmed by bivariate correlation analysis (RG index: r = 0.46, p = 0.001; Hyl index: r = 0.47, p = 0.001).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and proportions are used to describe categorical variables. A two-sided test was used, in which a p value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference between groups. For bivariate correlation analysis, Pearson correlation analysis was used when the two values followed a normal distribution, and Spearman analysis was used when the two values were nonnormally distributed. Because the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level exhibited nonnormal distributions, the distributions were adjusted by log transformation and analyzed as normally distributed variables. Multiple regression analysis was performed with the RG index or the Hyl index as the dependent variable and clinical and vascular function parameters as the independent variables. Multiple regression analysis of each clinical variable was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, and the presence or absence of hypertension. Multiple regression analysis of each vascular function parameter was adjusted for age, sex, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and pulse rate, which were found to affect the results of the vascular function test in model 1. In model 2, BMI and the use of antihypertensive agents, which affects the results of the vascular function test, as well as high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level and eGFRcysC, which were significant variables among the clinical variables, were further adjusted (HDL cholesterol level was excluded from the adjusting variables of the Hyl index due to lack of evidence of its relationship).

To estimate the effect of central systolic BP (cSBP) and PWV on histological lesions, patients were divided into two groups using the median value as a cutoff. The Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance test was used as a multiple comparison test to assess the categories of cSBP and PWV, and the Steel–Dwass test was used for post hoc analysis. Kendall’s tau-b was used for the intergroup ratio test of IF/TA. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Study population

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients. The average age was 32.4 ± 9.9 years, and the mean eGFRcysC and mean eGFRcr were 109.8 ± 32.1 and 85.9 ± 23.1 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively.

Nine patients (20.5%) had hypertension, with an average hypertension duration of 2.5 ± 1.9 years. There were eight smokers (18.2%) and one patient with hyperuricemia (2.3%). None of the patients had cardiovascular disease.

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy was the most common renal disease (75.0%), followed by minor glomerular abnormalities (13.6%) and nephrosclerosis in one patient (2.3%).

Brachial systolic BP (SBP) was 120.2 ± 13.5 mmHg, diastolic BP (DBP) was 75.3 ± 10.3 mmHg, MAP was 90.2 ± 10.3 mmHg, cSBP was 115.2 ± 17.9 mmHg, and cSBP was slightly lower than brachial SBP. baPWV was 12.1 ± 1.4 m/s. ABI was in the normal range at 1.2 ± 0.08.

Arteriolar wall thickening was found in 39.2 ± 22.7% of patients, and arteriolar hyalinosis was found in 37.4 ± 22.7% of the arterioles in all patients. The rate of global glomerulosclerosis was 9.1% (0.0, 22.2), and fibrous intimal thickening of the small arteries was mostly grade 0 (0, 2). Regarding other histological findings, IF/TA grade and InF grade remained within the range of G0–G2, and G3 was not observed.

We performed bivariate correlation analysis to identify variables associated with the RG index and Hyl index (Table 2). In addition to eGFRcr and eGFRcysC, the RG index was significantly correlated with several clinical variables, including HDL cholesterol levels, CRP, HbA1c, UACR levels, and smoking. The RG index was also significantly correlated with DBP, MAP, cSBP, central pulse pressure (cPP), and baPWV. However, the correlation of the RG index with SBP was of borderline significance. Histological findings, such as the global glomerulosclerosis rate, IF/TA grade, and InF grade, were also significantly correlated with the RG index. The Hyl index was significantly correlated with HbA1c, baPWV, and intimal thickening of the small arteries.

Multiple regression analysis including clinical variables showed that eGFRcysC and HDL cholesterol levels were significantly correlated with the RG index (Table 3). No clinical variable was correlated with the Hyl index.

We next performed multivariate analysis on arteriole lesions and vascular function test parameters (Table 4). The RG index was significantly associated with cSBP and cPP in both models 1 and 2. The Hyl index was significantly associated with baPWV in both models 1 and 2. Each of the correlations is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Further analysis was performed to clarify the associations between cSBP, PWV, and histological findings (Fig. 2). The characteristics of each subgroup of patients are shown in Supplementary Table 1a, b. The proportion of arterioles with arteriolar wall thickening was significantly higher in the group with high cSBP and high PWV than in the group with low cSBP and high PWV and the group with low cSBP and low PWV. There were no significant differences in the proportion of arteriolar hyalinosis among the groups. The proportion of global glomerulosclerosis in patients in each subgroup and the proportion of patients with each IF/TA grade are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The proportion of global glomerulosclerosis was significantly higher in the group with high cSBP and high PWV than in the group with low cSBP and low PWV. The proportion of high IF/TA grade tended to be higher in the group with high cSBP and high PWV.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that arteriolar wall thickening correlates with cSBP and that arteriolar hyalinosis correlates with baPWV. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate significant associations between central hemodynamics and small renal artery lesions in relatively young patients with preserved renal function.

Remodeling with medial thickening of the arterioles caused by hypertension has been shown not only in renal arterioles but also in small blood vessels of the subcutaneous tissue and omentum [3, 4].

Arterioles might induce inward remodeling and an increase in the M/L ratio in response to increased central arterial pressure, as demonstrated in animal models [26]. Moreover, such changes in the arterioles induce an increase in central arterial BP and peripheral organ damage. Our results are consistent with some studies showing an association between cSBP and peripheral organ damage [13,14,15].

The small arteries of hypertensive patients show various histological changes, such as intimal fibrous thickening, arteriolar wall thickening [2, 3], and arteriolar hyalinosis. These histological changes were associated with age [5], obesity [27], diabetes, postprandial hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia [28], uric acid [24], inflammation [29], and renal function [23, 24]. In the present study, associations were observed between arteriolar wall remodeling and renal function.

Arteriolar hyalinosis is considered a lesion containing protein and serum components exudating from the blood due to endothelial cell damage [30]. Arteriolar hyalinosis is associated with multiple factors, such as aging [5], hypertension, diabetes [25], uric acid [24], and the use of calcineurin inhibitors [31]. Arterioles with hyalinosis and luminal enlargement are associated with glomerular hypertrophy and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis-type lesions, and these lesions may be associated with the loss of autoregulation in arterioles [32]. The presence of arterioles with hyalinosis has been reported to predict future albuminuria and impaired renal function [33, 34] and may be associated with impaired renal function [7,8,9, 24].

In the present study, baPWV was significantly associated with the Hyl index in multivariate analysis. Central arterial BP and PWV have been reported to be significantly associated with urinary albumin excretion [35, 36]. Increased vascular pulsation indicated by aortic PWV might increase vascular stress and damage the vascular endothelium [1], resulting in hyaline deposition in the arterioles.

In the present study, renal function was associated with the RG index. Increased M/L in the arterioles might reduce intraglomerular pressure, decrease glomerular blood flow, and result in a decrease in GFR. In addition, an increased cSBP might lead to increased albuminuria [36] and peritubular capillary rarefaction [3]. eGFRcysC was significantly associated with the RG index, whereas eGFRcr did not show a significant association. Serum creatinine levels are affected by muscle volume and metabolism, whereas serum cystatin C levels are not. Therefore, these results might be explained by the more accurate assessment of renal function by eGFRcysC.

Although it is not clear why wall thickening of the renal arteriole was associated with central BP rather than brachial BP, central BP as a central hemodynamic parameter may accurately reflect the pressure reflex from the periphery, including the renal arterioles. On the other hand, the association between brachial BP and renal arteriolar remodeling may have been weakened by the irregular pressure increase in the brachial artery. Hashimoto and Ito [37] reported that cPP had a significant inverse correlation with GFR, even when corrected for mean BP.

In our study, the Hyl index was not associated with renal function. We speculate that the characteristics of the study population, which was composed of relatively young patients with preserved renal function, might have affected the results. However, baPWV was associated with arteriole damage, which may induce the subsequent deterioration of renal function. Our results are consistent with the results of previous studies regarding the association of PWV with peripheral organ damage and prognosis [19, 21, 22].

The effects of arterial stiffness caused by aging on hemodynamic parameters are important for understanding the interaction of hemodynamic parameters with renal injury. Central arterial BP increases linearly with age in healthy subjects [38], whereas PWV shows a relatively steep increase after 50 years of age [39]. PWV may be associated with more severe end-organ damage in the older population. The slow increase in PWV in younger patients may attenuate the association between baPWV and arteriolar wall thickening.

Few studies to date have aimed to clarify the association between central hemodynamics and small renal artery lesions. Namikoshi et al. reported that arteriolosclerosis in renal biopsy specimens did not correlate with patients’ central BP or cardio-ankle vascular index. This previous study included patients of older age and those with diabetes mellitus, and no distinction between arteriolar hyalinosis and arteriole thickening was made in the evaluation of arteriolosclerosis [23]. Zamami et al. [40] showed an association between ABI values in the normal range and intimal thickening of the small arteries; however, the arterioles were not analyzed. Although the authors observed an association between baPWV and small artery lesions, this association disappeared when the confounder of age was adjusted. This previous study and our present results indicate a poor association between baPWV and small artery remodeling, but this point requires further confirmation in the future.

Clinical implications

Lifestyle interventions reduce PWV and cSBP [41, 42]. Treatment with renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors suppresses remodeling of the smooth muscle of small arteries and rarefaction of peritubular capillaries [43]. Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive treatment is proportional to decreases in central arterial pressure and the augmentation index [44, 45]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that PWV was decreased by long-term treatment with antihypertensive drugs, even non-RAAS inhibitors [46]. These results suggest that the improvement in central hemodynamics caused by lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy might contribute to the suppression of structural alterations in the small renal arteries. Further studies are needed to determine whether maintaining appropriate levels of vascular function parameters will reduce histological damage in the kidney.

Limitations and strengths

Our study has several limitations. First, this study was a cross-sectional study, and it is not possible to show accurate causal relationships. The number of patients included in the study was small, and therefore, it was difficult to control for a large number of confounders. Second, cSBP was not directly measured but was estimated by arterial waveform analysis in the upper limb. Differences in the methods of measurement of PWV among patients might have affected the results; however, baPWV has been reported to correlate strongly with cfPWV [47]. Third, it was not possible to rule out the effects of sampling bias on the accuracy of the assessment of structural changes in the arterioles. In the arteriole assessment, there is a possibility that some small interlobular arteries were also evaluated. However, to minimize such contamination of the results, we evaluated the smallest arterioles located near the glomeruli, which are presumed to be continuous with the glomeruli. In addition, our histological methods used to evaluate arterioles were unique; the method resembled those used in several previous studies analyzing renal arterioles but was not exactly the same. Therefore, comparing our results with those of previous studies requires some caution. However, our results showing partial significance in the association between hemodynamic parameters and structural changes in arterioles indicate the validity of our histological evaluation methods. Finally, the subjects in our study were mostly Japanese and other Asian people, and hence, our results require caution in regard to their generalization to other populations. The strength of this study was the homogeneity regarding patient background, as the age was limited to younger than 50 years, and none of the patients had diabetes.

Conclusion

The present study indicated that abnormal central hemodynamics assessed by central arterial pressure and PWV are closely associated with structural injury of the small renal arteries in young to middle-aged patients with preserved renal function.

References

Mitchell GF. Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: implications for end-organ damage. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1652–60.

Feihl F, Liaudet L, Waeber B, Levy BI. Hypertension: a disease of the microcirculation? Hypertension. 2006;48:1012–7.

Renna NF, de Las Heras N, Miatello RM. Pathophysiology of vascular remodeling in hypertension. Int J Hypertens. 2013;2013:808353.

Hill GS, Heudes D, Jacquot C, Gauthier E, Bariéty J. Morphometric evidence for impairment of renal autoregulation in advanced essential hypertension. Kidney Int. 2006;69:823–31.

Kubo M, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Tanizaki Y, Katafuchi R, Hirakata H, et al. Risk factors for renal glomerular and vascular changes in an autopsy-based population survey: the Hisayama study. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1508–15.

Tracy RE, MacLean CJ, Reed DM, Hayashi T, Gandia M, Strong JP. Blood pressure, nephrosclerosis, and age autopsy findings from the Honolulu Heart Program. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:420–7.

Ikee R, Kobayashi S, Saigusa T, Namikoshi T, Yamada M, Hemmi N, et al. Impact of hypertension and hypertension-related vascular lesions in IgA nephropathy. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:15–22.

Zhang Y, Sun L, Zhou S, Xu Q, Xu Q, Liu D, et al. Intrarenal arterial lesions are associated with higher blood pressure, reduced renal function and poorer renal outcomes in patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43:639–50.

Shimizu M, Furuichi K, Toyama T, Kitajima S, Hara A, Kitagawa K, et al. Long-term outcomes of Japanese type 2 diabetic patients with biopsy-proven diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3655–62.

Moriya T, Omura K, Matsubara M, Yoshida Y, Hayama K, Ouchi M. Arteriolar hyalinosis predicts increase in albuminuria and GFR decline in normo- and microalbuminuric Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1373–8.

McGill HC Jr., Strong JP, Tracy RE, McMahan CA, Oalmann MC. Relation of a postmortem renal index of hypertension to atherosclerosis in youth. The Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Research Group. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:2222–8.

Burchfiel CM, Tracy RE, Chyou PH, Strong JP. Cardiovascular risk factors and hyalinization of renal arterioles at autopsy. The Honolulu Heart Program. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:760–8.

Ochi N, Kohara K, Tabara Y, Nagai T, Kido T, Uetani E, et al. Association of central systolic blood pressure with intracerebral small vessel disease in Japanese. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:889–94.

Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, O’Rourke MF, Safar ME, Baou K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with central haemodynamics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1865–71.

Roman MJ, Okin PM, Kizer JR, Lee ET, Howard BV, Devereux RB. Relations of central and brachial blood pressure to left ventricular hypertrophy and geometry: the Strong Heart Study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:384–8.

Briet M, Collin C, Karras A, Laurent S, Bozec E, Jacquot C, et al. Arterial remodeling associates with CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:967–74.

Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Asmar R, Gautier I, Laloux B, Guize L, et al. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001;37:1236–41.

Laurent S, Katsahian S, Fassot C, Tropeano AI, Gautier I, Laloux B, et al. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of fatal stroke in essential hypertension. Stroke. 2003;34:1203–6.

Briet M, Bozec E, Laurent S, Fassot C, London GM, Jacquot C, et al. Arterial stiffness and enlargement in mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:350–7.

Woodard T, Sigurdsson S, Gotal JD, Torjesen AA, Inker LA, Aspelund T, et al. Mediation analysis of aortic stiffness and renal microvascular function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1181–7.

Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982–92.

Horio M, Imai E, Yasuda Y, Watanabe T, Matsuo S. GFR estimation using standardized serum cystatin C in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:197–203.

Namikoshi T, Fujimoto S, Yorimitsu D, Ihoriya C, Fujimoto Y, Komai N, et al. Relationship between vascular function indexes, renal arteriolosclerosis, and renal clinical outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2015;20:585–90.

Kohagura K, Kochi M, Miyagi T, Kinjyo T, Maehara Y, Nagahama K, et al. An association between uric acid levels and renal arteriolopathy in chronic kidney disease: a biopsy-based study. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:43–9.

Bader H, Meyer DS. The size of the juxtaglomerular apparatus in diabetic glomerulosclerosis and its correlation with arteriolosclerosis and arterial hypertension: a morphometric light microscopic study on human renal biopsies. Clin Nephrol. 1977;8:308–11.

Prewitt RL, Chen II, Dowell RF. Microvascular alterations in the one-kidney, one-clip renal hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:H728–32.

Grassi G, Seravalle G, Scopelliti F, Dell’Oro R, Fattori L, Quarti-Trevano F, et al. Structural and functional alterations of subcutaneous small resistance arteries in severe human obesity. Obesity. 2010;18:92–8.

Ikee R, Honda K, Ishioka K, Oka M, Maesato K, Moriya H, et al. Postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia associated with renal arterio-arteriolosclerosis in chronic kidney disease. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:499–504.

Miyagi T, Kohagura K, Ishiki T, Kochi M, Kinjyo T, Kinjyo K, et al. Interrelationship between brachial artery function and renal small artery sclerosis in chronic kidney disease. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:863–9.

Biava CG, Dyrda I, Genest J, Bencosme SA. Renal hyaline arteriolosclerosis. an electron microscope study. Am J Pathol. 1964;44:349–63.

Snanoudj R, Royal V, Elie C, Rabant M, Girardin C, Morelon E, et al. Specificity of histological markers of long-term CNI nephrotoxicity in kidney-transplant recipients under low-dose cyclosporine therapy. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2635–46.

Hill GS, Heudes D, Bariéty J. Morphometric study of arterioles and glomeruli in the aging kidney suggests focal loss of autoregulation. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1027–36.

Bidani AK, Griffin KA. Pathophysiology of hypertensive renal damage: implications for therapy. Hypertension. 2004;44:595–601.

Zamami R, Kohagura K, Miyagi T, Kinjyo T, Shiota K, Ohya Y. Modification of the impact of hypertension on proteinuria by renal arteriolar hyalinosis in nonnephrotic chronic kidney disease. J Hypertens. 2016;34:2274–9.

Hashimoto J, Ito S. Central pulse pressure and aortic stiffness determine renal hemodynamics: pathophysiological implication for microalbuminuria in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58:839–46.

Tsioufis C, Tzioumis C, Marinakis N, Toutouzas K, Tousoulis D, Kallikazaros I, et al. Microalbuminuria is closely related to impaired arterial elasticity in untreated patients with essential hypertension. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;93:c106–11.

Hashimoto J, Ito S. Aortic blood flow reversal determines renal function: potential explanation for renal dysfunction caused by aortic stiffening in hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;66:61–7.

Takase H, Dohi Y, Kimura G. Distribution of central blood pressure values estimated by Omron HEM-9000AI in the Japanese general population. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:50–7.

Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness’ Collaboration. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘establishing normal and reference values’. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2338–50.

Zamami R, Ishida A, Miyagi T, Yamazato M, Kohagura K, Ohya Y. A high normal ankle-brachial index is associated with biopsy-proven severe renal small artery intimal thickening and impaired renal function in chronic kidney disease. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:929–37.

Hashimoto J. Central hemodynamics for management of arteriosclerotic diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:765–78.

Nordstrand N, Gjevestad E, Hertel JK, Johnson LK, Saltvedt E, Røislien J, et al. Arterial stiffness, lifestyle intervention and a low-calorie diet in morbidly obese patients-a nonrandomized clinical trial. Obesity. 2013;21:690–7.

Rule AD, Amer H, Cornell LD, Taler SJ, Cosio FG, Kremers WK, et al. The association between age and nephrosclerosis on renal biopsy among healthy adults. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:561–7.

Hashimoto J, Imai Y, O’Rourke MF. Indices of pulse wave analysis are better predictors of left ventricular mass reduction than cuff pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:378–84.

Hashimoto J, Westerhof BE, Westerhof N, Imai Y, O’Rourke MF. Different role of wave reflection magnitude and timing on left ventricular mass reduction during antihypertensive treatment. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1017–24.

Ong KT, Delerme S, Pannier B, Safar ME, Benetos A, Laurent S, et al. Aortic stiffness is reduced beyond blood pressure lowering by short-term and long-term antihypertensive treatment: a meta-analysis of individual data in 294 patients. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1034–42.

Tanaka H, Munakata M, Kawano Y, Ohishi M, Shoji T, Sugawara J, et al. Comparison between carotid-femoral and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity as measures of arterial stiffness. J Hypertens. 2009;27:2022–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Dr. Helena Akiko Popiel of the Department of International Medical Communications at Tokyo Medical University for her editorial review of the English manuscript. We also wish to thank Dr. Tatsuya Isomura of the Department of Clinical Consultation, Medical Research Institute, Tokyo Medical University, for providing statistical advice and the nephrologists of Tokyo Medical University for ensuring compliance with clinical study protocols.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miyaoka, Y., Okada, T., Tomiyama, H. et al. Structural changes in renal arterioles are closely associated with central hemodynamic parameters in patients with renal disease. Hypertens Res 44, 1113–1121 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00656-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00656-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association of macular microcirculation with renal function in Chinese non-diabetic patients with hypertension

Eye (2025)

-

Heterogeneous afferent arteriolopathy: a key concept for understanding blood pressure–dependent renal damage

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

Aerobic exercise improves central blood pressure and blood pressure variability among patients with resistant hypertension: results of the EnRicH trial

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Update on Hypertension Research in 2021

Hypertension Research (2022)