Abstract

Blood pressure (BP) exhibits seasonal variation, with an elevation of daytime BP in winter and an elevation of nighttime BP in summer. The wintertime elevation of daytime BP is largely attributable to cold temperatures. The summertime elevation of nighttime BP is not due mainly to temperature; rather, it is considered to be related to physical discomfort and poor sleep quality due to the summer weather. The winter elevation of daytime BP is likely to be associated with the increased incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in winter compared to other seasons. The suppression of excess seasonal BP changes, especially the wintertime elevation of daytime BP and the summertime elevation of nighttime BP, would contribute to the prevention of CVD events. Herein, we review the literature on seasonal variations in BP, and we recommend the following measures for suppressing excess seasonal BP changes as part of a regimen to manage hypertension: (1) out-of-office BP monitoring, especially home BP measurements, throughout the year to evaluate seasonal variations in BP; (2) the early titration and tapering of antihypertensive medications before winter and summer; (3) the optimization of environmental factors such as room temperature and housing conditions; and (4) the use of information and communication technology–based medicine to evaluate seasonal variations in BP and provide early therapeutic intervention. Seasonal BP variations are an important treatment target for the prevention of CVD through the management of hypertension, and further research is necessary to clarify these variations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is widely known that blood pressure (BP) shows variability due to physical activity, sleep, temperature, and living environments [1]. Several parameters of BP variability involving intraday, day-by-day, and visit-to-visit variation have been reported to be associated with the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) independent of BP levels [2,3,4,5,6]. Seasonal variation in BP is one phenotype of BP variability.

Seasonal variation in BP usually manifests as increased BP in winter and reduced BP in summer. Daytime BP, which includes morning and evening BP levels, has been reported to be higher in winter than in summer based on evaluations of office, ambulatory, and home BP measurements [7,8,9,10,11]. Epidemiological studies have revealed that the incidence of CVD is higher in winter than in summer [12, 13]. Elevated BP levels induced by vasoconstriction as a result of exposure to cold temperatures during winter are thought to be one of the risk factors for increased CVD incidence [7, 12,13,14,15]. Environmental factors such as outdoor or indoor temperatures have been reported to be strongly associated with BP levels [13, 16], and these factors may be the main causes of seasonal BP variation. Behavioral factors may also be associated with seasonal changes in BP [7]. Seasonal variation in BP has important clinical implications for the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Especially in hypertensive patients, the assessment of seasonal changes in BP would contribute to the optimal control of BP.

Here, we review the current evidence regarding seasonal variations in BP, and we present the best practices for managing hypertension while taking seasonal variation into consideration.

Seasonal variation in daytime blood pressure

Studies using office, ambulatory, and home BP measurements have shown that daytime BP, which includes both morning and evening BP, is higher in winter than in summer [10, 11, 13, 17,18,19,20,21]. Table 1 summarizes the existing findings regarding seasonal variations in office, ambulatory, and home BP. Home BP monitoring has been widely accepted as an effective tool for the management of hypertension [22,23,24]. Home BP monitoring can provide sustainable and repeatable measurements throughout the year, which is useful for detecting seasonal changes in BP. Several cohort studies have demonstrated that morning home BP is higher in winter than in summer and that the range of differences in home systolic BP (SBP)/diastolic BP (DBP) between winter and summer is 4–7/2–5 mmHg [10, 19, 20]. Kollias et al. performed a meta-analysis of seasonal variation in daytime BP, and they observed that the difference in daytime home BP (95% confidence interval: CI) between winter and summer was 6.1 (5.1, 7.0)/3.1 (2.6, 3.5) mmHg [8]. Investigations using ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) showed that the difference in daytime BP between winter and summer was 3–4/2–3 mmHg [17, 18, 25]. In a meta-analysis by Kollias et al., the difference in daytime ambulatory BP between winter and summer was 3.4 (2.4, 4.4)/2.1 (1.4, 2.8) mmHg [8].

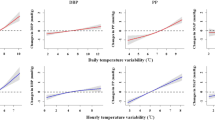

Environmental factors related to seasonal BP variation and the increasing incidence of CVD in winter

Environmental factors including outdoor and room temperature and housing conditions are suspected to play a major role in the mechanisms of seasonal BP variation. Weather-related changes in BP levels—specifically, increases in daytime (especially morning) ambulatory and home BP levels in cold outdoor temperatures—have been described [9, 16]. Saeki et al. reported that daytime ambulatory BP was more strongly associated with indoor temperatures than with outdoor temperatures [26]. A 1 °C increase in the outdoor temperature corresponded to a 0.28–0.40 mmHg decrease in home SBP in a study by Hozawa et al., but an inverse association between outdoor temperature and BP values was evident only during periods with outdoor temperatures >10 °C [20]. Morning home SBP was reported to be associated with the outdoor temperature (°C) (r = –0.253, p < 0.001) [11]. An association between the indoor room temperature and home BP was also observed [27, 28], and it has been reported that changes in room temperature are more strongly linked to morning home SBP than to evening home SBP (8.2 vs. 6.5 mmHg increase/10 °C decrease, respectively) [29].

The morning BP surge is greater at cold temperatures than at warm temperatures [30]. The sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin system are activated in the morning, and this activation is generally considered to be the reason for morning BP elevation [31, 32]. Cold temperatures activate sympathetic nervous tone and induce vascular constriction [25, 30]. In winter, therefore, cold temperatures in the morning induce a BP elevation known as a morning surge, which may partly account for the increase in CVD events in winter. Moreover, regarding the association between seasonal BP variation and target organ damage (TOD), our research group has demonstrated that morning home BP was more closely related to TOD parameters (including the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio [UACR] and level of brain-type natriuretic peptide [BNP]) in winter than in other seasons, but a similar relationship was not observed for evening home BP [21]. This finding indicated that elevated BP in winter might be related to the progression of hypertensive organ damage such as renal dysfunction and heart failure, which would be consistent with the increased incidence of CVD in winter [12, 13, 21].

Seasonal variation in nighttime blood pressure

Nighttime BP levels exhibit seasonal variation, with higher values in summer than in winter [9, 16, 18, 25, 33,34,35,36]. Nighttime ambulatory BP was reported to be a stronger predictor of CVD than daytime ambulatory BP [37, 38], and an association was reported between nighttime BP measured by a home BP device and the incidence of CVD [39]. Therefore, as with daytime BP, the seasonal variation in nighttime BP might be important for the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Earlier studies had focused on daytime BP in seasonal BP variation, but in 2006, Modesti et al. provided the first report that nighttime BP was higher in summer than in winter[16]. In other studies, nighttime ambulatory BP was reported to be higher in summer than in winter, with an SBP difference of 2–4 mmHg [9, 18, 33, 34]. A meta-analysis revealed that the difference in nighttime ambulatory BP between summer and winter was 1.3 (0.2, 2.3)/0.5 (−0.2, 1.8)[8]. Investigations of home BP indicated that nighttime home BP was also higher in summer than in winter, differing by ~5 mmHg between those seasons [35, 36].

Nocturnal BP dipping is also affected by seasonality, with larger dips in winter than in summer [30, 33]. The increased size of the nocturnal BP dip in winter might also be responsible for the increase in the morning BP surge. In a prospective observational study using ABPM, Nishizawa et al. observed that the morning surge was higher in winter than in summer [40]. Other research groups reported that the prevalence of the non-dipping (or riser) pattern was higher in summer (at ~70–85%) than in winter (at ~45–55%) [9, 33].

The pathological significance of the elevation of nighttime BP in summer

Although daytime BP increases in response to cold outdoor temperatures, it has been reported that nighttime ambulatory BP increases with warm outdoor temperatures [9, 16]. Decreases in sleep duration and quality may contribute to the increase in nighttime BP in summer. It has been hypothesized that the reduced sleep duration in summer and the mild, heat-induced perturbations in sleep are at least partly responsible for the nighttime BP elevation in summer [7, 9, 34]. Nocturia and sleep-disordered breathing also induce an elevation of nighttime BP [41,42,43,44]. The increased intake of fluids and salt in response to sweating and dehydration in summer has also been considered as possible a cause of nighttime BP elevation [35, 45]. However, both the frequency of nocturia and the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing have been reported to be higher in winter than in summer [46, 47]. It has been suggested that the elevation of nighttime BP in the summertime might not simply be related to sleep disturbances and might instead result from dietary changes in the summer [45].

Moreover, physicians often taper their patients’ antihypertensive medications due to their decreased daytime BP in summer, which could contribute to the elevation of nighttime BP [34]. Since ABPM or a home BP device that can take measurements at night should be used to evaluate nighttime BP, the elevation of nighttime BP is often difficult to recognize. In a cross-sectional study using a home device that can measure nighttime BP, our research group demonstrated that the prevalence of masked nocturnal hypertension (i.e., uncontrolled nighttime home BP despite controlled daytime home BP) was higher in summer than in the other seasons. In the same study, advanced age, diabetes, and elevated office BP were revealed to be significant risk factors for masked nocturnal hypertension in a multivariable logistic analysis [36]. Although the total numbers of CVD events such as stroke and coronary artery disease are highest in winter [12], several epidemiological studies have reported that nighttime CVD events occur more frequently in summer than in winter [48, 49]. In a Japanese epidemiological study that assessed seasonal variation in the incidence of each subtype of stroke among 47,782 stroke patients, the incidence rates of non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke (26% in summer vs. 24% in winter, p < 0.001) and lacunar stroke (27% in summer vs. 23% in winter, p < 0.001) were higher in summer than in winter [48]. Moreover, in a multiethnic and multinational study of 2270 ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients that investigated whether the circadian variation of STEMI onset is altered in the summer season, the difference between diurnal and nocturnal STEMI rates was markedly decreased in summer [49]. From these findings, it appears that nighttime BP might be an important parameter for the prevention of CVD events, especially in summer.

Seasonal variations in BP and mortality

The seasonal variations in BP can be summarized as follows: (1) daytime BP, especially morning BP, is higher in winter than in summer, and (2) nighttime BP is higher in summer than in winter [7, 8, 50]. Figure 1 illustrates the associations of seasonal BP variation with temperature, CVD events, and other factors such as environmental and behavioral variables. The total number of CVD events is higher in winter than in other seasons, and CVD events occur more often in the morning than in the evening or nighttime [12, 13, 15, 51]. These studies’ data demonstrate that there is an association between the seasonal variation in BP and the incidence of CVD. Specifically, elevated BP due to exposure to cold temperatures in winter may be associated with CVD mortality [12, 13, 15]. Regarding weather-related BP changes, Aubiniere-Robb et al. reported that hypertensive patients who exhibited higher BP in response to cold outdoor temperatures had increased all-cause mortality [52]. There are also several studies demonstrating an association between seasonal BP variation and CVD outcomes. Hanazawa et al. reported that the amplitude of the seasonal variation in BP, which they defined as the average of all increases in home BP from summer to winter, was associated with future CVD events. The inverse-variation group (i.e., patients with higher home BP values in summer than in winter) and the larger-variation group (the patients in whom the BP difference between winter and summer was ≥9.1/4.5 mmHg) both exhibited increases in the risk of CVD events compared to the small-variation group (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] in the inverse-variation group = 3.07, 95% CI: 1.44–6.54; adjusted HR in the larger-variation group = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.03–3.97) [53]. Although robust evidence of an association between seasonal BP variation and CVD mortality is still lacking, the larger seasonal BP difference might be related to the increased risk of CVD events.

The management of hypertension taking seasonal BP variation into consideration

For the suppression of seasonal changes in BP values, we recommend the following measures in the management of hypertension: (1) home BP measurements throughout the year to evaluate seasonal changes in BP; (2) early adjustment (titration or tapering) of antihypertensive medications; (3) the optimization of environmental factors such as room temperature and housing conditions; and (4) the use of information and communication technology (ICT)-based medicine to evaluate seasonal BP variations and provide early therapeutic intervention. Table 2 provides a summary of these recommendations.

Home BP monitoring to evaluate seasonal variations in BP

Various international guidelines on hypertension recommend out-of-office BP measurements (including home BP monitoring) in the management of hypertension [22,23,24]. Home BP monitoring, which has the advantage of sustainable measurement throughout the year as well as accuracy and reproducibility, is useful to evaluate seasonal variations in BP. Several prospective observational studies using home BP monitoring have assessed BP values throughout the year and demonstrated seasonal variation in BP [10, 20, 27, 53]. Although studies using ABPM assessed BP values in summer and winter [9, 16, 34, 40], it may be difficult to assess BP throughout the year due to constraints of ABPM, including the limited availability of monitoring devices and low tolerability among examinees. Our group demonstrated that the prevalence of masked hypertension (office BP < 140/90 mmHg and morning or evening home BP ≥ 135/85 mmHg) was higher in winter than in summer: in winter and summer, 50.6% and 30.5% of patients with controlled office BP had masked hypertension as defined by morning home BP, respectively [21]. The prevalence of white-coat hypertension was higher in summer than in winter (in summer and winter, 37.9% and 25.8% of patients with elevated office BP had white-coat hypertension as defined by morning home BP, respectively) [21]. Although there is not yet sufficient evidence of the superiority of home BP monitoring to office BP for the evaluation of seasonal BP variations, home BP monitoring might be useful to prevent misdiagnoses of elevated BP in winter and the administration of excessive antihypertensive treatment in summer.

In regard to the prevention of CVD events in winter, our research group demonstrated that morning home BP is associated with the future incidence of CVD events occurring in winter after adjusting for the season when the subjects’ baseline BP was measured (adjusted HR per 10 mmHg increase in SBP = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.06–1.42), but this association was not significant for evening home BP [54]. Morning home BP would thus be an important treatment target to prevent the incidence of CVD events in wintertime.

Early adjustment of antihypertensive medications

In clinical practice, antihypertensive medications are often tapered in summer and titrated in winter in response to seasonal BP changes. Hanazawa et al. reported that the winter-summer difference in home BP was smaller in an early titration group (September–November) than in a late titration group (December–February) (BP changes from summer to winter, 3.9/1.2 mmHg vs. 7.3/3.1 mmHg, p < 0.001), and they noted that this difference was also smaller in an early tapering group (March–May) than in a late tapering group (June–August) (BP changes from winter to summer, 4.2/2.1 mmHg vs. 7.1/3.4 mmHg, p < 0.001) [53]. In light of these findings, an early adjustment of antihypertensive medications using home BP monitoring would be effective to suppress the amplitude of seasonal BP variations.

Medical practitioners and hypertensive patients should take care to avoid excessive BP decreases in the summer. Although there is no robust evidence in support of specific criteria for the tapering of antihypertensive medications, international guidelines warn against antihypertensive treatment to SBP values <120 mmHg [22,23,24]. The consensus of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) working group in regard to seasonal variations in BP is that tapering of antihypertensive medications should be carefully considered in patients with SBP < 110 mmHg (office, home, or ambulatory) [7].

Optimization of room temperatures

Indoor room temperature has been demonstrated to be related to home BP parameters more strongly than outdoor temperature [26,27,28, 55]. Saeki et al. reported that instructions on home heating were effective for lowering subjects’ BP in a randomized trial [56]. The World Health Organization (WHO) Housing and Health Guidelines recommend that during wintertime, room temperatures be maintained at >18 °C [57]. Umishio et al. observed that the indoor ambient temperature at which there is a <50% probability of elevated morning home SBP (≥135 mmHg) is >12 °C for men aged 60 years, >19 °C for men aged 70 years, and >24 °C for men aged 80 years and >11 °C for women aged 70 years and >16 °C for women aged 80 years (Fig. 2) [29]. Based on the results of that study, the optimum room temperature should be decided by taking into account the characteristics of its residents, such as sex and age.

Relationship between home BP and room temperature. From Umishio [ref. [19]]

A cohort study in Scotland reported that people in housing heated to <18 °C had a greater risk of elevated BP [58]. In terms of the suppression of the elevation of BP in winter, the WHO’s recommendation to maintain room temperatures >18 °C is reasonable.

Using ICT-based medicine for the management of hypertension with consideration of the seasonal variation in BP

ICT-based medicine may be useful for the management of hypertension with the consideration of seasonal BP variation. Iwahori et al. described the seasonal variation in home BP in a study using home BP data that were automatically collected and simultaneously transmitted electronically to a web-based home BP monitoring platform [11]. Our research group also demonstrated that an ICT-based home BP monitoring system was useful for the evaluation of seasonal BP changes and the adjustment of the dose of antihypertensives, each of which helped patients suppress their seasonal BP amplitudes (Fig. 3) [55, 59, 60]. In the future, BP data obtained by a home, ambulatory, or wearable device could be combined with data on environmental and behavioral factors such as room temperature, sleep duration, and physical activity via an ICT system. These data could then be shared with medical institutions to prevent excessive seasonal BP changes and reduce the incidence of CVD events [61, 62].

Management of hypertension using an information and communication technology (ICT)-based home BP device. Our research group observed that the use of an ICT-based home BP monitoring system helped patients achieve strict BP control and suppress the amplitude of their seasonal BP fluctuations. From Nishizawa [ref. [59]]

Conclusions

In the management of hypertension, seasonal variation in BP may be an important treatment target for the prevention of CVD events. In order to assess seasonal variations in BP precisely, out-of-office BP measures such as home BP are recommended. Optimal adjustments of room temperature and the doses of antihypertensive medications should be considered to prevent excess seasonal changes in BP. In addition, ICT-based medicine will be a useful method for managing hypertension while considering seasonal variations in BP. Based on the many reported findings regarding seasonal variations in BP, the pathological significance of seasonal changes in BP is becoming increasingly clear. However, further accumulation of scientific evidence regarding the seasonal variation in BP is needed.

References

Parati G. Blood pressure variability: its measurement and significance in hypertension. J Hypertens. 2005;23:S19–S25.

Palatini P, Reboldi G, Beilin LJ, Casiglia E, Eguchi K, Imai Y, et al. Added predictive value of night-time blood pressure variability for cardiovascular events and mortality: the Ambultory Blood Pressure-International Study. Hypertension. 2014;64:487–93.

Hansen TW, Thijs L, Li Y, Boggia J, Kikuya M, Björklund-Bodegård K, et al. Prognostic value of reading-to-reading blood pressure variability over 24 h in 8939 subjects from 11 populations. Hypertension 2010;55:1049–57.

Johansson JK, Niiranen TJ, Pukka PJ, Jula AM. Prognostic value of the variability in home-measured blood pressure and heart rate: the Finn-Home study. Hypertension. 2012;59:212–8.

Hoside S, Yano Y, Mizuno H, Kanegae H, Kario K. Day-by-day variability of home blood pressure and incident cardiovascular disease in clinical practice: The J-HOP study (Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure). Hypertension. 2018;71:177–84.

Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O’Brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlöf B, et al. Prognositc significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375:895–905.

Stergiou GS, Palatini P, Modesti PA, Asayama K, Asmar R, Bilo G, et al. Seasonal variation in blood pressure: evidence, consensus and recommendations for clinical practice. Consensus statement by the European Society of Hypertension working group on blood pressure monitoring and cardiovascular variability. J Hypertens. 2020;38:1235–43.

Kollias A, Kyriakoulis KG, Stambolliu E, Ntineri A, Anagnostopoulos I, Stergiou GS. Seasonal blood pressure variation assessed by different measurement methods: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2020;38:791–8.

Stergiou GS, Myrsilidi A, Kollias A, Destounis A, Roussias L, Kalogeropoulos P. Seasonal variation in meteorological parameters and office, ambulatory and home blood pressure: predicting factors and clinical implications. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:869–75.

Hanazawa T, Asayama K, Watabe D, Hosaka M, Satoh M, Yasui D, et al. Seasonal variation in self-measured home blood pressure among patients on antihypertensive medications: HOMED-BP study. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:284–90.

Iwahori T, Miura K, Obayashi K, Ohkubo T, Nakajima H, Shiga T, et al. Seasonal variation in home blood pressure: findings from nationwide web-based monitoring in Japan. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e017351.

The Eurowinter Group. Cold exposure and winter mortality from ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, respiratory disease, and all causes in warm and cold regions of Europe. The Eurowinter Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1341–6.

Yang L, Li L, Lewington S, Guo Y, Sherliker P, Bian Z, et al. China Kadoorie Biobank Study Collaboration. Outdoor temperature, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease mortality among 23,000 individuals with diagnosed cardiovascular disease from China. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1178–85.

Morabito M, Crisci A, Orlandini S, Maracchi G, Gensini GF, Modesti PA. A synoptic approach to weather conditions discloses a relationship with ambulatory blood pressure in hypertensives. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:748–52.

Gaspattini A, Guo Y, Hashizume M, Lavigne E, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J, et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observation study. Lancet. 2015;386:369–75.

Modesti PA, Morabito M, Bertolozzi I, Massetti G, Panci G, Lumachi C, et al. Weather-related changes in 24-hour blood pressure profile: Effects of age and implications for hypertension management. Hypertension. 2006;47:155–61.

Sega R, Cesana G, Bombelli M, Grassi G, Stella ML, Zanchetti A, et al. Seasonal variations in home and ambulatory blood pressure in the PAMELA population. Pressione Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1585–92.

Minami J, Kawano Y, Ishimitsu T, Yoshimi H, Takishita S. Seasonal variations in office, home and 24h ambulatory blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1996;14:1421–5.

Kimura T, Senda S, Masugata H, Yamagami A, Okuyama H, Kohno T, et al. Seasonal blood pressure variation and its relationship to environmental temperature in healthy elderly Japanese studied by home measurements. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;32:8–12.

Hozawa A, Kuriyama S, Shimazu T, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Tsuji I. Seasonal variation in home blood pressure measurements and relation to outside temperature in Japan. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2011;33:153–8.

Narita K, Hoshide S, Fujiwara T, Kanegae H, Kario K. Seasonal variation of home blood pressure and its association with target organ damage: The J-HOP Study (Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure). Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:620–8.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–324.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–104.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Winnicki M, Canali C, Accurso V, Dorigatti F, Giovinazzo P, Palatini P. Relation of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and short-term blood pressure variability to seasonal changes in environmental temperature in stage I hypertensive subjects. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1996;18:995–1012.

Saeki K, Obayashi K, Iwamoto J, Tone N, Okamoto N, Tomioka K, et al. Stronger association of indoor temperature than outdoor temperature with blood pressure in colder months. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1582–9.

Imai Y, Munakata M, Ohkubo T, Satoh H, Yoshino H, Watanabe N, et al. Seasonal variation in blood pressure in normotensive women studied by home measurements. Clin Sci. 1996;90:55–60.

Yatabe J, Yatabe MS, Morimoto S, Watanabe T, Ichihara A. Effects of room temperature on home blood pressure variations: Findings from a long-term observational study in Aizumisato Town. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:785–7.

Umishio W, Ikaga T, Kario K, Fujino Y, Hoshi T, Ando S, et al. SWH Survey Group. Cross-sectional analysis of the relationship between home blood pressure and indoor temperature in winter: A Nationwide Smart Wellness Housing Survey in Japan. Hypertension. 2019;74:756–66.

Murakami S, Otsuka K, Kono T, Soyama A, Umeda T, Yamamoto N, et al. Impact of outdoor temperature on prewaking morning surge and nocturnal decline in blood pressure in a Japanese population. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:70–73.

Kario K, Pickering TG, Hoshide S, Eguchi K, Ishikawa J, Morinari M, et al. Morning blood pressure surge and hypertensive cerebrovascular disease. Role of the alpha adrenergic sympathetic nervous system. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:668–75.

Naito Y, Tsujino T, Fujioka Y, Ohyanagi M, Iwasaki T. Augmented diurnal variations of the cardiac renin-angiotensin system in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2002;40:827–33.

Fedecostante M, Barbatelli P, Guerra F, Espinosa E, Dessì-Fulgheri P, Sarzani R. Summer does not always mean lower: Seasonality of 24 h, daytime, and night-time blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1392–8.

Modesti PA, Morabito M, Massetti L, Rapi S, Orlandini S, Mancia G, et al. Seasonal blood pressure changes: an independent relationship with temperature and daylight hours. Hypertension. 2013;61:908–14.

Tabara Y, Matsumoto T, Murase K, Nagashita S, Kosugi S, Nakayama T, et al. and the Nagahama Study Group. Seasonal variation in nocturnal home blood pressure fall: The Nagahama study. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:198–208.

Narita K, Hoshide S, Kanegae H, Kario K Seasonal variation in masked nocturnal hypertension: The J-HOP Nocturnal Blood Pressure Study. Am J Hypertens. 2020 Nov 27; hpaa193. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpaa193. Online ahead of print.

Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Cesana G, Corrao G, Grassi G, et al. Prognosis value of ambulatory and home blood pressure compared with office blood pressure in the general population: Follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Association (PAMELA) study. Circulation. 2005;111:1777–83.

Boggia J, Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Björklund-Bodegård K, et al. International Database on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes (IDACO) investigators. Prognostic accuracy of day versus night ambulatory blood pressure: a cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370:1219–29.

Kario K, Kanegae H, Tomitani N, Okawara Y, Fujiwara T, Yano Y, et al. Group., on behalf of the J-HOP Study. Nighttime blood pressure measured by home blood pressure monitoring as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events in general practice. Hypertension. 2019;73:1240–8.

Nishizawa M, Fujiwara T, Hoshide S, Sato K, Okawara Y, Tomitai N, et al. Winter morning surge in blood pressure after the Great East Japan Earthquake. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019;21:208–16.

Matsumoto T, Tabara Y, Murase K, Setoh K, Kawaguchi T, Nagashima S, et al. Nagahama Study Group. Nocturia and increase in nocturnal blood pressure: the Nagahama Study. J Hypertens. 2018;36:2185–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001802

Ohishi M, Kubozono T, Higuchi K, Akasaki Y. Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and nocturia: a systematic review of the pathophysiological mechanisms. Hypertens Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00634-0

Thomas SJ, Booth JN 3rd, Jaeger BC, Hubbard D, Sakhuja S, Abdalla M, et al. Association of sleep characteristics with nocturnal hypertension and non-dipping blood pressure in the CARDIA Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015062.

Hoshide S, Kario K, Chia YC, Siddique S, Buranakitjaroen P, Tsoi K, et al. Characteristics of hypertension in obstructive sleep apnea: an Asian experience. J Clin Hypertens. 2021;23:489–95.

Modesti PA. Season, temperature and blood pressure: a complex interaction. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:604–7.

Yoshimura K, Kamoto T, Tsukamoto T, Oshiro K, Kinukawa N, Ogawa O. Seasonal alterations in nocturia and other storage symptoms in three Japanese communities. Urology 2007;69:864–70.

Cassol CM, Martinez D, Silva FABS, Fischer MK, Lenz MD, Bós AJG. Is sleep apnea a winter disease? Meteorologic and sleep laboratory evidence collected over 1 decade. Chest. 2012;142:1499–507.

Takizawa S, Shibata T, Takagi S, Kobayashi S, Japan Standard Stroke Registry Study Group. Seasonal variation of stroke incidence in Japan for 35631 stroke patients in the Japanese standard stroke registry, 1998–2007. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:36–41.

Cannistraci CV, Nieminen T, Nishi M, Khachigian LM, Viikilä J, Laine M, et al. “Summer shift”: A potential effect of sunshine on the time onset of ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e006878.

Modesti PA, Rapi S, Rogolino A, Tosi B, Galanti G. Seasonal blood pressure variation: Implications for cardiovascular risk stratification. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:475–82.

Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1989;79:733–43.

Aubinière-Robb L, Jeemon P, Hastie CE, Patel RK, McCallum L, Morrison D, et al. Blood pressure response to patterns of weather fluctuations and effect on mortality. Hypertension. 2013;62:190–6.

Hanazawa T, Asayama K, Watabe D, Tanabe A, Satoh M, Inoue R, et al. Association between amplitude of seasonal variation in self-measured home blood pressure and cardiovascular outcomes: HOMED-BP (Hypertension Objective Treatment Based on Measurement By Electrical Devices of Blood Pressure) Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008509.

Narita K, Hoshide S, Kario K Relationship between home blood pressure and the onset season of cardiovascular events: The J-HOP Study (Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure). Am J Hypertens. 2021; hpab016. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpab016.

Park S, Kario K, Chia YC, Turana Y, Chen CH, Buranakitjaroen P, et al. HOPE Asia Network. The influence of the ambient temperature on blood pressure and how it will affect the epidemiology of hypertension in Asia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22:438–44.

Saeki K, Obayashi K, Kurumatani N. Short-term effects of instruction in home heating on indoor temperature and blood pressure in elderly people: a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2015;33:2338–43.

WHO. Housing and Health Guidelines. 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550376. Accessed Dec 26, 2020.

Shiue I, Shiue M. Indoor temperature below 18°C accounts for 9% of population attributable risk for high blood pressure in Scotland. Int J Cardiol. 2014;171:e1–e2.

Nishizawa M, Hoshide S, Okawara Y, Matsuo T, Kario K. Strict blood pressure control achieved using an ICT-based home blood pressure monitoring system in a catastrophically damaged area after a disaster. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:26–29.

Kario K, Tomitani N, Kanegae H, Yasui N, Nishizawa M, Fujiwara T, et al. Development of a new ICT-based multisensory blood pressure monitoring system for use in hemodynamic biomarker-initiated anticipation medicine for cardiovascular disease: the national IMPACT program project. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60:435–49.

Kario K. Management of hypertension in the digital era: Small wearable monitoring devices for remote blood pressure monitoring. Hypertension. 2020;76:640–50.

Kario K, Chia YC, Sukonthasarn A, Turana Y, Shin J, Chen CH, et al. Diversity of and initiatives for hypertension management in Asia–Why we need the HOPE Asia Network. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22:331–43.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KK takes primary responsibility for this paper. KN wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

KK has received research funding from Teijin Pharma Limited, Omron Healthcare Co., Fukuda Denshi, Bayer Yakuhin Ltd., A&D Co., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., EA Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim Japan Inc., Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharma Corp., Shionogi & Co., MSD K.K., Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., and Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K., as well as honoraria from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. and Omron Healthcare Co.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Narita, K., Hoshide, S. & Kario, K. Seasonal variation in blood pressure: current evidence and recommendations for hypertension management. Hypertens Res 44, 1363–1372 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00732-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00732-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension 2025 (JSH2025)

Hypertension Research (2026)

-

Impact of treatment strategies incorporating sacubitril/valsartan on achievement of guideline-recommended blood pressure targets and representative safety outcomes

Hypertension Research (2026)

-

Associations of free triiodothyronine and thyroxine with blood pressure in Chinese coronary artery disease adults

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2025)

-

Air pollution and the number of daily visits of hypertension in northern china: a time-series analysis on generalized additive model

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A retrospective study of seasonal variation in sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor-related adverse events using the Japanese adverse drug event report database

Scientific Reports (2024)