Abstract

Intensive lipid-lowering therapy is recommended in individuals exhibiting type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with microvascular complications (as high-risk patients), even without known cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, evidence is insufficient to stratify the patients who would benefit from intensive therapy among them. Hypertension is a major risk factor, and uncontrolled blood pressure (BP) is associated with increased CVD risk. We evaluated the efficacy of intensive vs. standard statin therapy for primary CVD prevention among T2DM patients with retinopathy stratified by BP levels. We used the dataset from the EMPATHY study, which compared intensive statin therapy targeting low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels of <70 mg/dL and standard therapy targeting LDL-C levels ranging from ≥100 to <120 mg/dL in T2DM patients with retinopathy without known CVD. A total of 4980 patients were divided into BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg (systolic BP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 80 mmHg, n = 3335) and BP < 130/80 mmHg (n = 1645) subgroups by baseline BP levels. During the median follow-up of 36.8 months, 281 CVD events were observed. Consistent with previous studies, CVD events occurred more frequently in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup than in the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup (P < 0.001). In the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup, intensive statin therapy was associated with lower CVD risk (HR 0.70, P = 0.015) than standard therapy after adjustment. No such association was observed in the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup. The interaction between BP subgroup and statin therapy was significant. In conclusion, intensive statin therapy targeting LDL-C < 70 mg/dL provided benefits in primary CVD prevention when compared with standard therapy among T2DM patients with retinopathy and BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels with the use of statins is effective in reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1, 2]. Recent guidelines have recommended intensive lipid-lowering therapy for the primary prevention of CVD in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who have diabetic microvascular complications [3, 4]. However, the EMPATHY study, which is the first and only large randomized trial of T2DM patients with diabetic retinopathy and hyperlipidemia in a primary prevention setting of CVD to evaluate the beneficial effects of intensive statin therapy with a target LDL-C level of <70 mg/dL compared with standard therapy with an LDL-C target of ≥100 to <120 mg/dL, failed to show the benefits of intensive statin therapy [5]. Therefore, the evidence remains insufficient in terms of identifying patients who would benefit from intensive statin therapy among such high-risk diabetic patients without prior CVD.

Hypertension is a major risk factor for CVD. Patients without prior CVD but with multiple risk factors, including hypertension, T2DM, and hyperlipidemia, are considered at very high risk of CVD. The guidelines recommend the target of office blood pressure (BP) < 130/80 mmHg (systolic BP < 130 mmHg and diastolic BP < 80 mmHg) in patients with hypertension and T2DM [6,7,8]. However, there is currently no evidence demonstrating whether the efficacy of intensive statin therapy is affected by baseline BP levels among T2DM patients in a primary prevention setting of CVD.

In the present study, we hypothesized that intensive statin therapy has benefits for the primary prevention of CVD in T2DM patients with diabetic microvascular complications who have high BP levels, specifically BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg, and are considered to be at higher risk than those who have BP < 130/80 mmHg. Using the data from the EMPATHY study, which enrolled T2DM patients with retinopathy and hyperlipidemia without known CVD, we examined the efficacy of intensive vs. standard statin therapy for the prevention of CVD among T2DM patients stratified by BP levels at baseline.

Methods

Data collection

This study is a subanalysis of patients from the EMPATHY study (clinical trial registration: https://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr.; unique identifier, UMIN000003486), which was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with Japanese ethical guidelines for clinical studies. This subanalysis was approved by the ethics committee of Kyushu University. The design of the EMPATHY study has been previously reported in detail [5]. In brief, T2DM patients who had diabetic retinopathy and elevated LDL-C levels (≥120 mg/dL without lipid-lowering drug[s] or ≥100 mg/dL with lipid-lowering drug[s]) were included. Patients with a history of coronary artery disease, stroke, familial hypercholesterolemia, or renal failure (serum creatinine level of ≥2.0 mg/dL or estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] of <30 mL/min/1.73 m2) were excluded from analysis. The use of a lipid-lowering drug other than statins was prohibited during the study period. Patients were randomly assigned to standard therapy targeting an LDL-C level ranging from ≥100 to <120 mg/dL or intensive therapy targeting an LDL-C level of <70 mg/dL. Because the originally categorized data of the prescribed drugs were insufficient to be included in this subanalysis, we opted to recategorize drug types based on the drug names in the original dataset from the EMPATHY study.

Stratification by baseline BP levels and/or the presence of diagnosed hypertension

In the EMPATHY study, BP was recorded at clinics or hospitals with the patient in the sitting position. In this current subanalysis, we used the average value of two BP measurements at registration and randomization as the baseline BP. We then divided the patients into the following two subgroups based on their baseline BP: BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg (systolic BP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 80 mmHg) and BP < 130/80 mmHg (systolic BP < 130 mmHg and diastolic BP < 80 mmHg). As an alternative to the baseline BP levels, we stratified this population based on whether the patient was diagnosed with hypertension regardless of baseline BP levels (i.e., patients with diagnosed hypertension and patients without hypertension). In addition, we divided the patients into four subgroups according to baseline BP levels (BP of ≥130/80 mmHg or <130/80 mmHg) and the presence of diagnosed hypertension.

Outcomes

The primary outcome in this subanalysis was the composite incidence of CVD events, including cardiac, cerebral, renal, and vascular events or death associated with cardiovascular events, which was the same primary outcome as in the EMPATHY study [5]. Cardiac events included myocardial infarction, unscheduled hospitalization due to unstable angina, and coronary artery revascularization. Cerebral events included ischemic stroke and cerebral revascularization. Renal events included the initiation of chronic dialysis or serum creatinine level >1.5 mg/dL with an increase of ≥2-fold from the value at registration. Vascular events also included aortic or peripheral arterial disease consisting of aortic dissection, mesenteric artery thrombosis, severe lower-limb ischemia (ulceration), revascularization, and amputation of the finger/lower limb caused by arteriosclerosis obliterans. Furthermore, we analyzed two other defined outcomes, namely, nonrenal CVD events and major adverse cardiac events (MACEs). Nonrenal CVD events were defined as composite endpoints, which included cardiac, cerebral, and vascular events or death associated with cardiovascular events, excluding renal events from the primary outcome. MACE was defined as a composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, stroke (ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, or subarachnoid hemorrhage), or death associated with cardiovascular events.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation and were analyzed using t-tests, except for special notes. All categorical variables were expressed as raw numbers and percentages and were compared using a chi-square test. We compared Kaplan–Meier cumulative incidence curves by a log-rank test between the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg and BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroups. We then compared Kaplan–Meier curves between intensive and standard statin therapy groups within each BP subgroup. We also used multivariate Cox proportional hazards models to calculate the hazard ratios for the incidence of the events in the intensive statin therapy group compared to the standard statin therapy group within each BP subgroup. To adjust for confounding factors, we constructed the following three models. Model 1 included an EMPATHY therapy assignment (intensive or standard statin therapy), sex, and age. Model 2 additionally included body mass index (BMI), smoking, hypertension, heart rate, duration of diabetes, diabetic neuropathy, diabetic nephropathy, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), LDL-C, and eGFR. Model 3 additionally included information on the prescribed antihypertensive drugs [angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), diuretics, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), α-blockers, and β-blockers], antiplatelet drugs, standard statins, and strong statins.

Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using JMP 14 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study participants

In total, 5042 patients were included in the EMPATHY study. In this study, we excluded 62 patients because of a lack of BP data. We thus analyzed data from 4980 patients with 281 composite CVD events, including 119 cardiac, 64 cerebral, 100 renal, and 16 vascular events during a median follow-up period of 36.8 (range, 0.17–65.7) months.

Patient characteristics in baseline BP subgroups

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the patients in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup (n = 3335) and BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup (n = 1645). Mean systolic and diastolic BP values were 141.8 and 78.5 mmHg in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup and 120.0 and 68.0 mmHg in the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup, respectively. Compared with the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup, a greater proportion of the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup had comorbid hypertension and diabetic nephropathy. Body mass index, HbA1c, and LDL-C were higher in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup than in the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup. A greater proportion of patients in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup than in the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup received CCBs, diuretics, and ARBs.

Comparison of the incidence of CVD between the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg and BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroups

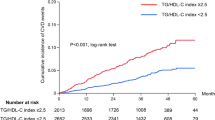

Figure 1a presents the Kaplan–Meier curves showing a comparison of the incidence of the composite CVD outcomes as the primary outcome between the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg and BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroups. The incidence of CVD was significantly higher in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup than in the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup (P < 0.001).

Cumulative incidence for the primary outcome (composite CVD events) stratified by baseline BP levels. a BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg vs. BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroups. b Intensive vs. standard statin therapy groups within the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup. c Intensive vs. standard statin therapy groups within the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup. CVD cardiovascular disease, BP blood pressure

Patient characteristics by statin therapy in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg and BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroups

Table 2 presents the baseline characteristics of patients receiving intensive and standard statin therapy in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg and BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroups. In the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup, no significant difference was observed in terms of the baseline characteristics other than the use of strong statins and standard statins between intensive and standard therapies. In the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup, a greater proportion of patients had diabetic nephropathy and received CCBs and diuretics, and a smaller proportion of these individuals received standard statins in the intensive therapy group than in the standard therapy group. Mean systolic and diastolic BP during the follow-up period did not significantly differ between the intensive and standard statin therapy groups in each BP subgroup.

Comparison of the incidence of CVD between the statin-intensive and standard therapy groups

Figure 1b and c present the Kaplan–Meier curves showing a comparison of the incidence of the composite CVD outcomes between the intensive and standard statin therapy groups in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup and BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup, respectively. In the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup, the incidence of CVD was lower among patients receiving intensive therapy than among those receiving standard therapy (P = 0.022; Fig. 1b). In the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup, no such difference was noted regarding the incidence of CVD between the intensive and standard statin therapy groups (Fig. 1c).

Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that intensive statin therapy was associated with a lower incidence of primary composite CVD than was standard therapy after adjusting for age, sex, known risks of CVD, antihypertensive drugs, antiplatelet drugs, and statins in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup (using Model 3, hazard ratio: 0.70, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.52–0.93, P = 0.015; Table 3). This hazard ratio using Model 3 was similar to that using Model 2 without antihypertensive drugs, antiplatelet drugs, or statins (hazard ratio: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.52‒0.91, P = 0.009; Table 3). In addition, compared with standard therapy, intensive statin therapy was associated with a lower risk of nonrenal CVD and MACE in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup (using Model 3, hazard ratios: 0.67 and 0.67, 95% CIs: 0.47‒0.95 and 0.44‒1.02, P = 0.025 and 0.064, respectively; Table 3). Intensive therapy was not associated with primary composite CVD, nonrenal CVD, or MACE in the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup. The interaction between the BP subgroup and the therapy group was significant for the primary composite outcome of CVD and MACE (P = 0.027 and 0.017, respectively, in Model 3; Table 3). The analysis with an additional model adjusting for all the confounders in Model 3 and mean systolic and diastolic BP during the follow-up period showed similar results as the analysis with Model 3 (Supplementary Table 1).

Analyses based on stratification by the presence of diagnosed hypertension

In addition to the analyses based on the stratification by baseline BP levels, we performed analyses based on the stratification by the presence of diagnosed hypertension. As per our findings, significant differences were noted between the patients with diagnosed hypertension [Dx-HTN(+) subgroup] and without hypertension [HTN(−) subgroup] in several characteristics associated with increased CVD risk, such as age, BMI, BP, and diabetic complications (Supplementary Table 2). In the HTN(−) subgroup, only a small number of subjects were treated with antihypertensive drugs such as ARBs, ACEIs, diuretics, CCBs, and β-blockers (Supplementary Table 2). It was assumed that these antihypertensive drugs were prescribed for indication(s) other than hypertension, such as diabetic nephropathy (ARB/ACEI), edema (diuretic), and tachyarrhythmia (CCB/β-blocker), although the actual indication(s) could not be determined from the available dataset of the EMPATHY study. The Kaplan–Meier curve showed that the incidence of CVD was significantly higher in patients with diagnosed hypertension than in those without hypertension (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The proportion of patients with diabetic nephropathy among those with diagnosed hypertension and the diastolic BP and LDL-C levels among those without hypertension were higher in the intensive statin therapy group than in the standard therapy group (Supplementary Table 3). The results of the univariate analysis with Kaplan–Meier curves (Supplementary Fig. 1b and 1c) and the results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis (Supplementary Table 4) demonstrated that there were no significant differences in the incidence of the primary composite CVD between the two therapy groups in patients with diagnosed hypertension and without hypertension. Multivariate analysis indicated that intensive therapy was not associated with nonrenal CVD or MACE (Supplementary Table 4).

Analyses based on stratification by baseline BP levels and the presence of diagnosed hypertension

We additionally divided the patients into four subgroups according to baseline BP levels (BP of ≥130/80 mmHg or <130/80 mmHg) and the presence of diagnosed hypertension (with diagnosed hypertension or without hypertension): BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg/Dx-HTN(+) (n = 2653), BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg/HTN(−) (n = 682), BP < 130/80 mmHg/Dx-HTN(+) (n = 881), and BP < 130/80 mmHg/HTN(−) (n = 764) subgroups. The multivariate analysis showed that intensive statin therapy was associated with a lower risk of primary composite CVD outcome than standard therapy in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg/Dx-HTN(+) subgroup (hazard ratio: 0.73, P = 0.043) and the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg/HTN(−) subgroup (hazard ratio: 0.54, P = 0.17) (Supplementary Table 5). However, these beneficial effects of intensive statin therapy were not observed in the BP < 130/80 mmHg/Dx-HTN(+) subgroup (hazard ratio 1.82, P = 0.070) or the BP < 130/80 mmHg/HTN(−) subgroup (hazard ratio: 0.96, P = 0.94). The interaction between the presence of diagnosed hypertension and statin therapy was not significant in the patients with a baseline BP of ≥130/80 mmHg or those with a baseline BP of <130/80 mmHg (P = 0.36 and 0.28, respectively; Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

This analysis of the EMPATHY study is the first to investigate the efficacy of intensive vs. standard statin therapy for the primary prevention of CVD among T2DM patients with retinopathy stratified by baseline BP levels. Intensive statin therapy with a target LDL-C of <70 mg/dL significantly reduced the risk of composite CVD compared with standard statin therapy with a target LDL-C ranging from ≥100 to <120 mg/dL in T2DM patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg but not in those with BP < 130/80 mmHg.

In T2DM patients with diabetic microvascular complications, intensive lipid-lowering therapy can be beneficial for the primary prevention of CVD, as indicated by recent guidelines [3, 4]. However, the original EMPATHY study showed that intensive statin therapy targeting an LDL-C level of <70 mg/dL was not significantly associated with a greater reduction in CVD risk among T2DM patients with retinopathy without known CVD [5]. Furthermore, there remains no sufficient evidence to allow for the stratification of patients who will benefit from intensive statin therapy among such high-risk T2DM patients. In patients with hypertension and T2DM, the recommended target BP is <130/80 mmHg, where patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg are considered to be at risk of CVD [6,7,8,9]. In this study, when we divided patients into the two subgroups of T2DM patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg and BP < 130/80 mmHg, the incidence of CVD was significantly higher in patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg than in those with BP < 130/80 mmHg (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the use of intensive statin therapy was associated with a lower risk of the primary composite CVD outcome than standard therapy in patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg but not in those with BP < 130/80 mmHg (Table 3, Fig. 1b and 1c). As shown in Table 1, BMI, heart rate, LDL-C, and HbA1c values were significantly higher among patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg than among those with BP < 130/80 mmHg, all of which have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of CVD [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Together, these results demonstrated that among T2DM patients exhibiting retinopathy without prior CVD, those with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg could receive more beneficial effects from intensive statin therapy than subjects with BP < 130/80 mmHg because the former are “higher-risk” T2DM patients. Considering that the original EMPATHY study failed to show the benefits of intensive statin therapy in this population with T2DM, stratification by baseline BP levels (BP of ≥130/80 or <130/80 mmHg) might be a novel strategy for determining target LDL-C levels in statin lipid-lowering therapy for the primary prevention of CVD among T2DM patients with microvascular complications.

The primary outcome in this study was the same as that in the original EMPATHY study and included renal events, whereas CVD, as commonly defined, does not include renal events. Therefore, in addition to the primary composite CVD outcome, we analyzed the hazard ratios for nonrenal CVD and MACE in the intensive therapy group compared with the standard therapy group in each BP subgroup (Table 3). Among patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg, intensive statin therapy reduced the risk of nonrenal CVD and MACE as well as the primary composite CVD outcome compared with standard therapy. We did not observe any benefits of intensive statin therapy among patients with BP < 130/80 mmHg. These results indicated that T2DM patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg could benefit from intensive statin therapy for the primary prevention of nonrenal CVD and MACE as well as the composite CVD outcome, including renal events.

We also performed analyses based on stratification by comorbid hypertension as an alternative to baseline BP levels because T2DM patients with comorbid hypertension have been reported to have a higher risk of CVD than those without hypertension [16]. In this study, the incidence of CVD was significantly higher in patients with diagnosed hypertension than in those without hypertension (Supplementary Fig. 1a). However, unlike when the patients were divided by baseline BP levels, no significant differences were noted in the incidence of the primary composite CVD outcome, nonrenal CVD, or MACE between the groups receiving intensive and standard statin therapy in the patient subgroups with diagnosed hypertension and without hypertension (Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Fig. 1b and c), although the precision of the results might have been limited by the smaller number of events in patients without hypertension after this alternative stratification. In the analyses based on stratification by baseline BP levels, multivariate analysis demonstrated the benefits of intensive statin therapy for the prevention of CVD after adjusting for confounders, including hypertension as a comorbidity, in T2DM patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg but not in those with BP < 130/80 mmHg (Table 3). In addition, when we stratified the patients into four subgroups according to baseline BP levels and the presence of diagnosed hypertension, compared with standard therapy, intensive statin therapy was associated with lower risk of the primary composite CVD outcome in both the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg/Dx-HTN(+) subgroup (hazard ratio: 0.73, P = 0.043) and the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg/HTN(−) subgroup (hazard ratio: 0.54, P = 0.17), but not in the BP < 130/80 mmHg/Dx-HTN(+) subgroup (hazard ratio: 1.82, P = 0.070) or BP < 130/80 mmHg/HTN(−) subgroup (hazard ratio: 0.96, P = 0.94) (Supplementary Table 5). A meta-analysis examining the effects of lowering BP in cases of T2DM showed that T2DM patients who achieved a systolic BP of <130 mmHg were at significantly lower risk of CVD than those who achieved a systolic BP of ≥130 mmHg [17]. This supports the concept that risk stratification based on whether T2DM patients with retinopathy have a baseline BP of ≥130/80 mmHg, but not on whether those patients have hypertension as a comorbidity, may be useful, which is suggested by our results.

There are several possible mechanisms responsible for the benefits of intensive statin therapy for the prevention of CVD among T2DM patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg. Here, we focused on several factors stratified by baseline BP levels, which can be associated with the effects of statin therapy. First, the baseline LDL-C levels of the patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg were significantly higher than those with BP < 130/80 mmHg (Table 1). Patients with higher baseline LDL-C levels might receive the benefits of intensive statin therapy through a greater LDL-C-lowering action. Second, the heart rate, which can be a marker of sympathetic activity [18], was significantly higher in patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg at baseline than in those with BP < 130/80 mmHg (Table 1). Sympathoexcitation plays a crucial role in CVD [19, 20], and statins have been reported to have a sympathoinhibitory effect [21, 22]. Therefore, in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup, intensive statin therapy might have attenuated the increased sympathetic activity and reduced CVD events. Third, vasculopathy, including vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, might progress more severely in T2DM patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg. The severity of vasculopathy has been determined to be correlated with BP levels [23, 24], and the coexistence of hypertension contributes to accelerated vasculopathy in T2DM patients [25]. Statins have anti-inflammatory effects and act to improve endothelial function [26,27,28]. T2DM patients in the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup who are at higher risk of vasculopathy might benefit from intensive statin therapy through greater effects on the vasculature.

Experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated the synergistic beneficial effects of statins, antihypertensive drugs, and antiplatelet drugs, independent of BP levels [29,30,31,32,33,34], suggesting that the differences in prescribed antihypertensive drugs and antiplatelet drugs could have affected the CVD outcome in this study. Therefore, in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, we constructed Model 3, which included the use of antihypertensive drugs, antiplatelet drugs, and statins, in addition to Model 2, which included age, sex, smoking, HbA1c, and other known risk factors for CVD. After adjusting for these potential confounders with Model 3, we found that intensive statin therapy was independently associated with a lower risk of CVD and MACE than standard therapy among patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg but not in those with BP < 130/80 mmHg (Table 3). In patients with BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg, the hazard ratio for the primary composite CVD outcome with Model 3 was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.52‒0.93), which was similar to that with Model 2 (hazard ratio: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.52‒0.91), indicating that the differences in these prescribed drugs contributed little to the efficacy of intensive vs. standard statin therapy. Moreover, a statistically significant interaction was observed between the BP subgroup and statin therapy group in the primary composite CVD in the multivariate analysis with Model 3. Based on these results, we consider that the efficacy of intensive vs. standard statin therapy might differ depending on whether patients with T2DM have a baseline BP of ≥130/80 mmHg but independent of the prescribed antihypertensive drugs, antiplatelet drugs, and statins.

In the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup, the cumulative incidence of CVD was higher in intensive statin therapy than in standard therapy (Fig. 1c), and the hazard ratios for the primary composite CVD outcome, nonrenal CVD, and MACE in intensive statin therapy compared to standard therapy were more than 1.0, although not statistically significant (Table 3). We consider that these increased events might be associated with the following adverse effects of intensive statin therapy: renal function impairment and hemorrhagic stroke. It has been reported that the use of high-dose statins compared with low-dose statins is associated with an increase in acute kidney injury [35]. In the EMPATHY study, most patients in intensive statin therapy were assumed to be treated with higher-dose statins to reduce LDL-C levels below 70 mg/dL. The patients with baseline BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg were at high risk of CVD and might have been more likely to benefit from intensive statins. In contrast, the patients with baseline BP < 130/80 mmHg were at comparatively lower CVD risk and might have experienced the adverse effects of intensive statin therapy, such as renal function impairment, rather than the beneficial effects. The hazard ratio for nonrenal CVD in intensive vs. standard therapy was lower than that for the primary composite CVD outcome, including renal events (hazard ratio: nonrenal CVD, 1.28; primary composite CVD, 1.56), among the patients with a baseline BP of <130/80 mmHg, suggesting that renal events may be involved in the increased cumulative incidence of primary composite CVD in intensive statin therapy within the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup. Furthermore, although the P value was 0.45, the hazard ratio for nonrenal CVD of 1.28 (>1.0) suggests that intensive statins might cause increased adverse effects other than renal injury in this subgroup. In the present study, hemorrhagic strokes were included in MACE but not in primary composite CVD or nonrenal CVD, and renal events were not included in MACE. It has also been reported that high-dose statin therapy is associated with a small increase in the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke while reducing the overall incidence of CVD, including strokes, in patients with prior stroke [36]. Therefore, intensive statin therapy might have caused the increased incidence of MACE with increasing hemorrhagic strokes in the BP < 130/80 mmHg subgroup, which was at a comparatively lower risk of CVD, as the adverse effects of intensive statin therapy might outweigh its benefits.

Study limitations

There are several limitations in the present study. First, this was a post hoc subanalysis of the EMPATHY study, a relatively large randomized trial with more than 5000 patients. To confirm whether baseline BP levels affect the efficacy of lipid-lowering therapy with statins and to determine the target LDL-C levels for statin lipid-lowering therapy in a primary prevention setting among T2DM patients with microvascular complications, further retrospective and prospective studies are needed that will include patients stratified by baseline BP levels. Second, the EMPATHY study did not include lipid-lowering agents other than statins. Therefore, we did not analyze the efficacy of other lipid-lowering agents, such as ezetimibe or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor, which have been reported to be effective in lowering the risk of CVD [37]. Third, the EMPATHY study did not include T2DM patients with diabetic neuropathy and/or nephropathy but without retinopathy. However, as the CVD risk is considered to be similar among T2DM patients with each diabetic microvascular complication [11], the results of our analysis could be generalized to T2DM patients with diabetic complication(s) other than retinopathy.

Conclusion

Intensive statin lipid-lowering therapy with a target LDL-C level of <70 mg/dL was associated with a lower risk of composite CVD events than standard therapy with a target LDL-C of ≥100 to <120 mg/dL among the BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg subgroup of T2DM patients with diabetic retinopathy without known CVD. These associations were not observed in T2DM patients with BP < 130/80 mmHg. As per the results of this study, intensive statin therapy might not be equivalently effective among high-risk patients with hyperlipidemia and diabetic retinopathy, which further suggests that stratification based on whether T2DM patients have a baseline BP of ≥130/80 mmHg might be a novel and useful strategy for determining target LDL-C levels in statin lipid-lowering therapy for the primary prevention of CVD among T2DM patients with microvascular complications.

References

Mills EJ, Rachlis B, Wu P, Devereaux PJ, Arora P, Perri D. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Mortality and Events With Statin Treatments. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1769–81.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18 686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:117–25.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:e177–e232. 2019

Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, et al. ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:255–323.

Itoh H, Komuro I, Takeuchi M, Akasaka T, Daida H, Egashira Y, et al. Intensive Treat-to-Target Statin Therapy in High-Risk Japanese Patients With Hypercholesterolemia and Diabetic Retinopathy: report of a randomized study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1275–84.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American Heart Association task. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–324. 2017

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Rosei EA, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. ESC/ESH Guidelines for themanagement of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–104. 2018

Imai Y, Hirata T, Saitoh S, Ninomiya T, Miyamoto Y, Ohnishi H, et al. Impact of hypertension stratified by diabetes on the lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in Japan: a pooled analysis of data from the Evidence for Cardiovascular Prevention from Observational Cohorts in Japan study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:1437–44.

Newman JD, Schwartzbard AZ, Weintraub HS, Goldberg IJ, Berger JS. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Diabetes Mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:883–93.

Brownrigg JRW, Hughes CO, Burleigh D, Karthikesalingam A, Patterson BO, Holt PJ, et al. Microvascular disease and risk of cardiovascular events among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a population-level cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:588–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30057-2

Selvin E, Marinopoulos S, Berkenblit G, Rami T, Brancati FL, Powe NR, et al. Meta-analysis: Glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00007

Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Grassi G. Heart rate as a predictor of cardiovascular risk. Eur J Clin Investig. 2018;48:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12892

Kokubo Y. Associations of impaired glucose metabolism and dyslipidemia with cardiovascular diseases: what have we learned from Japanese cohort studies for individualized prevention and treatment? EPMA J. 2011;2:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13167-011-0074-1

Nishimura K, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Nakai M, Takegami M, Higashiyama A, et al. Predicting coronary heart disease using risk factor categories for a Japanese urban population, and comparison with the Framingham risk score: the Suita study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2014;21:784–98. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.19356

Chen G, McAlister FA, Walker RL, Hemmelgarn BR, Campbell NRC. Cardiovascular outcomes in framingham participants with diabetes: the importance of blood pressure. Hypertension. 2011;57:891–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162446

Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, Callender T, Perkovic V, Patel A. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2015;313:603–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.18574

Quarti Trevano F, Seravalle G, Macchiarulo M, Villa P, Valena C, Dell’Oro R, et al. Reliability of heart rate as neuroadrenergic marker in the metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens. 2017;35:1685–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001370

Grassi G, Bombelli M, Brambilla G, Trevano FQ, Dell’oro R, Mancia G. Total cardiovascular risk, blood pressure variability and adrenergic overdrive in hypertension: evidence, mechanisms and clinical implications. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012;14:333–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-012-0273-8

Kishi T. Heart failure as an autonomic nervous system dysfunction. J Cardiol. 2012;59:117–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2011.12.006

Lewandowski J, Symonides B, Gaciong Z, Siński M. The effect of statins on sympathetic activity: a meta-analysis. Clin Auton Res. 2015;25:125–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-015-0274-1

Millar PJ, Floras JS. Statins and the autonomic nervous system. Clin Sci. 2014;126:401–15.

Figueiredo VN, Yugar-Toledo JC, Martins LC, Martins LB, De Faria APC, De Haro Moraes C, et al. Vascular stiffness and endothelial dysfunction: correlations at different levels of blood pressure. Blood Press. 2012;21:31–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/08037051.2011.617045

Fujii M, Tomiyama H, Nakano H, Iwasaki Y, Matsumoto C, Shiina K, et al. Differences in longitudinal associations of cardiovascular risk factors with arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflection in middle-aged Japanese men. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:98–106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0523-0

Petrie JR, Guzik TJ, Touyz RM. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:575–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.005

Oesterle A, Laufs U, Liao JK. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins on the Cardiovascular System. Circ Res. 2017;120:229–43. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308537

Ridker PM. Clinician’s Guide to Reducing Inflammation to Reduce Atherothrombotic Risk: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3320–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.082

Mason RP, Walter MF, Jacob RF. Effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on endothelial function: role of microdomains and oxidative stress. Circulation. 2004;109:II34–41. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000129503.62747.03

Horiuchi M, Cui TX, Li Z, Li JM, Nakagami H, Iwai M. Fluvastatin enhances the inhibitory effects of a selective angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, valsartan, on vascular neointimal formation. Circulation. 2003;107:106–12. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000043244.13596.20

Clunn GF, Sever PS, Hughes AD. Calcium channel regulation in vascular smooth muscle cells: synergistic effects of statins and calcium channel blockers. Int J Cardiol. 2010;139:2–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.05.019

Sever P, Dahlöf B, Poulter N, Wedel H, Beevers G, Caulfield M, et al. Potential synergy between lipid-lowering and blood-pressure-lowering in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2982–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehl403

Koh KK, Sakuma I, Shimada K, Hayashi T, Quon MJ. Combining potent statin therapy with other drugs to optimize simultaneous cardiovascular and metabolic benefits while minimizing adverse events. Korean Circ J. 2017;47:432–9. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.0406

Sundström J, Gulliksson G, Wirén M. Synergistic effects of blood pressure-lowering drugs and statins: systematic review and meta-Analysis. Evid Based Med. 2018;23:64–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110888

Hennekens CH, Sacks FM, Tonkin A, Jukema JW, Byington RP, Pitt B, et al. Additive Benefits of Pravastatin and Aspirin to Decrease Risks of Cardiovascular Disease: randomized and Observational Comparisons of Secondary Prevention Trials and Their Meta-analyses. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:40–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.1.40

Dormuth CR, Hemmelgarn BR, Paterson JM, James MT, Teare GF, Raymond CB, et al. Use of high potency statins and rates of admission for acute kidney injury: multicenter, retrospective observational analysis of administrative databases. BMJ. 2013;346:f880 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f880

Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A, Gold- LB, Hennerici M, Rudolph AE, et al. High-Dose Atorvastatin after Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549–59. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa061894

Wilson PWF, Polonsky TS, Miedema MD, Khera A, Kosinski AS, Kuvin JT. Systematic Review for the 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:E1144–E1161. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000626

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

KS reports grants from Daiichi Sankyo and Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim. HI reports grants and/or personal fees from Shionogi, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Kyowa Kirin, Ono Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Novartis Pharma, Kao, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Oriental Yeast, Abbott Japan, Bayer Yakuhin, LifeScan Japan, SBI Pharmaceuticals, Nipro, and Wakunaga Pharmaceutical. IK reports grants and/or personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Astellas Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, MSD, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Novartis Pharma, Bayer Yakuhin, Pfizer Japan, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Japan, and Teijin Pharma. HT reports grants and/or personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer Japan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Teijin Pharma, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Yakuhin, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Ono Pharmaceutical, Kowa, Japan Tobacco, IQVIA Service Japan, Omron Healthcare, MEDINET, Medical Innovation Kyushu, Abbott Medical Japan, Teijin Home Healthcare, and Boston Scientific Japan. The other authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shinohara, K., Ikeda, S., Enzan, N. et al. Efficacy of intensive lipid-lowering therapy with statins stratified by blood pressure levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and retinopathy: Insight from the EMPATHY study. Hypertens Res 44, 1606–1616 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00734-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00734-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Triglyceride/high density lipoprotein cholesterol index and future cardiovascular events in diabetic patients without known cardiovascular disease

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Update on Hypertension Research in 2021

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Intensive lipid-lowering therapy in high-risk diabetic patients

Hypertension Research (2021)