Abstract

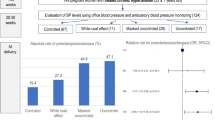

To test the hypothesis that nocturnal hypertension identifies risk for early-onset preeclampsia/eclampsia (PE), we conducted an historical cohort study of consecutive high-risk pregnancies between 1st January 2016 and 31st March 2020. Office blood pressure (BP) measurements and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) were performed. The cohort was divided into patients without PE or with early- or late-onset PE (<34 and ≥34 weeks of gestation, respectively). The relative risks of office and ABPM hypertension for the development of late- or early-onset PE were estimated with multinomial logistic regression using no PE as a reference category. Four hundred and seventy-seven women (mean age 30 ± 7 years, with 23 ± 7 weeks of gestation at the time of the BP measurements) were analyzed; 113 (23.7%) developed PE, 69 (14.5%) developed late-onset PE, 44 (9.2%) developed early-onset PE. Office and ambulatory BP increased between the groups, and women who developed early-onset PE had significantly higher office and ambulatory BP values than those with late-onset PE or without PE. Hypertension prevalence increased across groups, with the highest values in early-onset PE. Nocturnal hypertension was the most prevalent finding and was highly prevalent in women who developed early-onset PE (88.6%); only 1.6% of women without nocturnal hypertension developed early-onset PE. Additionally, nocturnal hypertension was a stronger predictor for early-onset PE than for late-onset PE (adjusted OR, 5.26 95%CI 1.67–16.60) vs. 2.06, 95%CI 1.26–4.55, respectively). In conclusion, nocturnal hypertension was the most frequent BP abnormality and a significant predictor of early-onset PE in high-risk pregnancies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preeclampsia/eclampsia (PE) is a leading cause of neonatal and maternal morbidity and mortality. In PE, the fetus is exposed to the risk of intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity and intrauterine death; maternal risks include placental abruption, stroke, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Overall, PE severity varies widely [1,2,3,4].

In 1996, Ness and Roberts published a seminal paper highlighting the heterogeneity of preeclampsia, suggesting that “maternal preeclampsia” differs from “placental preeclampsia” based on the extent of trophoblastic invasion during the first and early second trimesters of pregnancy, as well as rates of fetal growth restriction. They proposed that “placental preeclampsia” was linked to early-onset PE but that “maternal preeclampsia” was linked to late-onset PE [5]. Nevertheless, there remains considerable debate regarding the paradigm that early-onset PE is associated with lack of spiral artery remodeling and that late-onset PE may center around interactions between senescence of the placenta and a maternal predisposition toward cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [6].

Published data support the notion that early- and late-onset PE are different phenotypes of pregnancy with different maternal and fetal consequences. In a population-based study of ~450,000 pregnancies in Washington State between 2003 and 2008, Lisonkova et al. showed that risk factors differ significantly in their association with early- vs. late-onset PE, with antecedents for chronic hypertension having a stronger association with early-onset PE than with late-onset PE. Remarkably, this study showed that the rates of adverse birth outcomes were significantly higher among women with early-onset PE. Furthermore, very low birthweight and perinatal death were several times more frequent in early-onset than in late-onset PE [7]. Thus, identifying women who may develop early-onset PE has great clinical importance, as most of the burden of maternal and fetal disease occurs with this phenotype. There is a consensus that a cutoff of 34 weeks of gestation differentiate between early- and late-onset PE [6].

We have recently published that nocturnal hypertension is the most common abnormality of hypertensive disorders of women with high-risk pregnancies and a strong predictor of PE (five times more risk) [8] and that it may constitute an early finding, several weeks before clinically evident disease [9]. Moreover, nocturnal hypertension is a frequent finding in women with normal office blood pressure (BP) values and essentially a masked condition [10]. Because ABPM is the most reliable method to detect nocturnal hypertension, it has been suggested that it might become a mandatory approach in high-risk pregnancies [11, 12].

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies analyzing possible relationships between nocturnal hypertension and early-onset PE. The aim of this study was to analyze the possible relationships between nocturnal hypertension and early-onset PE in high-risk pregnant women.

Material and methods

This is a historical cohort study of consecutive women with high-risk pregnancies who visited the high-risk pregnancy office of the Obstetrics Department at San Martín Hospital, (La Plata, Argentina) between 1st January 2016 and 31st March 2020. They had been referred to the obstetric specialized office by primary care physicians either because of comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease or others, or because of certain findings detected during that pregnancy (gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension or multiple pregnancy).

Data extraction

Data for the pregnant women were extracted from the predefined electronic medical recordings in the Cardiometabolic Diseases Unit. These medical recordings were designed before the beginning of and were unchanged during the study. Data on delivery and perinatal outcomes—APGAR score (appearance, pulse, grimace, activity and respiration) and birth weight—were extracted from the default protocol used by the Obstetrics Department.

Blood pressure measurement and the definition of hypertension

All women were tested with a defined protocol for office and ambulatory BP measurement. This protocol, which includes the routine use of ABPM in all high-risk pregnancies, has been incorporated as usual medical practice at our hospital since 2016. The protocol has been previously described [8]. In brief, at the end of a 15-min interview, a specially trained nurse performs three BP measurements using appropriate arm sleeves and a validated oscillometric automatic BP device (OMRON HEM 705 CP) for a patient in a seated position with the arm at heart level. Office BP was defined as an average of these three determinations; office hypertension was defined as BP of at least 140/90 mmHg. Immediately after this measurement, ABPM with a validated monitor (Spacelabs 90207) was initiated. Measurements were carried out every 15 min during the day and every 20 min at night. ABPM with at least 70% successful measurements and at least one record per hour was considered valid. Only women who had at least one valid ABPM evaluation after 10 weeks and before 34 weeks of gestation and whose deliveries occurred in San Martin Hospital were included in the analysis.

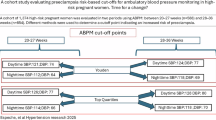

Office hypertension was defined as systolic office BP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic office BP ≥ 90 mmHg. Hypertension for 24-h ABPM was defined as systolic ABPM ≥ 130 and/or diastolic ABPM ≥ 80 mmHg [13]. Night and day periods, defined considering the patient’s diary, were analyzed separately. Daytime hypertension was defined as day ABPM ≥ 135 and/or 85 mmHg for systolic and diastolic BP, respectively; nocturnal hypertension was defined as ABPM during night rest ≥120 and/or 70 mmHg for systolic and diastolic BP, respectively [13]. Additionally, isolated nocturnal hypertension was defined as nocturnal hypertension with daytime BP < 135/85 mmHg, isolated daytime hypertension as daytime hypertension with nocturnal BP < 120/70 mmHg, and sustained hypertension as hypertension in both periods [14, 15].

End-point definitions

PE was defined as the presence of any of the following: 1—preeclampsia (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg associated with proteins in urine ≥ 300 mg/24 h), 2—eclampsia (seizures in a patient with preeclampsia or gestational hypertension), or 3—HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and low platelet count). Current definitions allow preeclampsia to be diagnosed when hypertension is accompanied by signs of end-organ injury. However, because of the date of the beginning of the cohort, proteinuria was a required criterion for this study; consequently, nonproteinuric preeclampsia, except HELLP syndrome, was not identified. PE was classified according to the time of development as early-onset PE (developed before 34 weeks of gestation) and late-onset PE (developed at ≥34 weeks of gestation) [16, 17]. The cohort was divided into three categories: no PE, late-onset PE, and early-onset PE.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared between groups using ANOVA and post hoc Scheffe test, and the results are expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Ordinal variables were compared with the Kruskal–Wallis H test; the results are expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared with the Χ2 or Fisher exact test, and the results are expressed as percentages.

Relative risks of office and ABPM hypertension for the development of late- or early-onset PE were estimated with multinomial logistic regression using no PE as the reference category. Three models were constructed: Model 1, unadjusted; Model 2, adjusted by BP (office hypertension by systolic and diastolic ABPM, ABPM hypertension by office BP, daytime hypertension by nocturnal BP and nocturnal hypertension by daytime BP); Model 3 included Model 2 plus maternal age at the time of BP measurement (years), gestational age at ABPM (weeks), chronic hypertension (yes/no), and treatments at ABPM (yes/no) (antihypertensive drugs, low doses of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), and calcium supplement). Finally, to evaluate the contribution of each BP component, systolic and diastolic, daytime, and nocturnal BP as continuous variables were evaluated using multinomial regression. Daytime systolic ABPM was adjusted by nocturnal systolic ABPM, and vice versa; daytime diastolic ABPM was adjusted by nocturnal diastolic ABPM, and vice versa.

As some degree of collinearity between office, ambulatory, daytime and nocturnal BP may occur, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were estimated using 5 as the cutoff point to define high collinearity [17]. If high collinearity was detected, one of the variables with collinearity was excluded. Goodness-of-fit was estimated for fully adjusted multinomial regression models; two measures were used to assess how well the model fits the data: the Pearson chi-square statistic and deviation chi-square statistic. A statistically significant result (p < 0.05) indicated that the model did not well fit the data.

Unadjusted and adjusted risks are expressed as odds ratios (ORs), with a confidence interval of 95% (95% CI). The data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA); p values < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered significant.

The study protocol was designed by the Institutional Teaching and Research Department and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (HSMLP2020/0037).

Results

Maternal characteristics and perinatal outcomes

Six hundred ninety-six high-risk pregnant women were evaluated; 17 women were evaluated before 10 weeks of gestation and 192 at or after 34 weeks of gestation; 10 without valid ABPM were excluded (Fig. 1). The remaining 477 women (mean age 30 ± 7 years, with 23 ± 7 weeks of gestation at the time of the BP evaluation) were included in the present analysis. One hundred and sixteen women (24.3%) were nulliparous; multiparous women had a median of 2 (IQR 1–4) pregnancies. The cohort had a high-risk profile, and 23.3%, 8.4%, 4.0%, and 2.7% had a history of hypertension, diabetes, collagen diseases or antiphospholipid syndrome and chronic renal disease, respectively. In previous pregnancies, 10.7% had gestational diabetes; 21.0% had reported elevations in BP. Furthermore, at the time of BP evaluations, 23.1% were taking antihypertensive drugs, 36.9% were taking ASA, and 31.4% were taking calcium supplements.

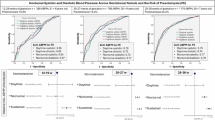

One hundred thirteen (23.7%) developed PE; 69 (14.5%) had late-onset PE (67 preeclampsia, 2 eclampsia and no HELLP cases) and 44 (9.2%) early-onset PE (40 preeclampsia, no eclampsia cases and 4 HELLP cases). The absolute risks of late-onset PE were 10.5%, 0%, 18.2% and 21.1% for normal ABPM in both periods, isolated daytime hypertension, isolated nocturnal hypertension, and sustained hypertension, respectively. Similarly, the absolute risks of early-onset PE were 2.0%, 0%, 13.6%, and 21.1% for normal ABPM in both periods, isolated daytime hypertension, isolated nocturnal hypertension, and sustained hypertension, respectively. Thus, compared with normal ABPM, isolated nocturnal hypertension increased the risk for late- and early-onset PE (unadjusted OR 1.96, 95%CI 1.06–3.62 and unadjusted OR 7.63, 95%CI 2.67–21.86, respectively).

All the patients who developed PE were admitted to the hospital and treated with labetalol and/or α-methyldopa (to reach a BP < 160/100 mmHg); delivery was indicated after attempting pulmonary fetal maturation using betamethasone. Table 1 shows the maternal characteristics and perinatal outcomes of the cohort divided according to the status at delivery, no PE, late-onset PE, and early-onset PE. Only antecedents of chronic renal disease were significantly associated with early-onset PE. Compared with no PE, all perinatal outcomes were worst in newborns of patients with late- or early-onset PE. Additionally, perinatal outcomes were significantly worse in newborns delivered by women with early-onset PE than in those delivered by women with late-onset PE.

There were three stillborn infants, one in the group without PE (0.3%), none in the group with late-onset PE (0%) and two (4.5%) in the early-onset PE group. There was no maternal mortality.

Blood pressure values and hypertension prevalence

Office and ambulatory BP values showed a stepwise increase between groups, with the lowest values in the no-PE group and highest in the early-onset PE group; late-onset PE had intermediate values (Table 2). These higher BP values were found some weeks before the development of overt PE in both late- and early-onset PE. Post hoc analysis showed that compared with the no-PE group, office BP and ABPM were higher in women who developed late- or early-onset PE. In addition, women who developed early-onset PE had significantly higher office and ambulatory BP values than those with late-onset PE (Table 2).

In agreement, the prevalence of hypertension increased in a stepwise manner through the groups, with the highest values in the early-onset PE group (Table 3). Hypertension defined by ABPM was more frequent than office hypertension in all groups. Nocturnal hypertension was the most prevalent finding and was highly prevalent in women who developed early-onset PE (88.6%). Indeed, the absence of nocturnal hypertension (several weeks before clinical apparent disease) indicated very improbable early-onset PE, with only 5 of the 322 women without nocturnal hypertension (1.6%) developing early-onset PE.

Risk for the development of early-onset PE

Table 4 shows the ORs for the development of late- and early-onset PE. In the unadjusted model, both office and ABPM hypertension predicted the subsequent development of early-onset PE. However, after adjustment for BP (office hypertension by ABPM pressure and ABPM by office BP), only ABPM hypertension was statistically significant. Women who had nocturnal hypertension showed a high risk of developing early-onset PE, and the risk remained significant after adjustment for daytime BP. Conversely, daytime hypertension was not an independent predictor after adjustment for nocturnal BP. In all analyses, further adjustment for maternal age, antecedents of diabetes or hypertension and treatments did not substantially modify the OR values. No multicollinearity was detected (VIF < 5).

Finally, Table 5 shows that in unadjusted models, the increase in daytime and nocturnal systolic and diastolic ABPM as continuous variables were associated with a greater risk of both late- and early-onset PE. When daytime and nocturnal values were included in the same regression model, nocturnal systolic and diastolic ABPM (but not daytime) remained significant predictors.

Discussion

Our data show that nocturnal hypertension is a significant predictor of early-onset PE in high-risk pregnant women and remains significant after adjustment for the daytime BP level. Moreover, nocturnal hypertension can precede the development of PE by several weeks (Table 2). Additionally, nocturnal hypertension in ABPM was the most frequent finding in women who subsequently developed early-onset PE (~90%), at a rate almost twice that of office hypertension. Our results are concordant with previously published studies [18, 19]. Brown et al. found that hypertension during sleep is a common finding in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, particularly PE, and that it was related to a high risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Women with nocturnal hypertension had a significantly greater frequency of renal insufficiency, liver dysfunction, thrombocytopenia, and lower birth weight. In this cohort, ~80% of women who developed PE had elevated BP during the sleep period [18]. The present study expands these findings, specifically with regard to relationships between nocturnal hypertension and early-onset PE.

Brown et al. found that awake and sleeping BP are higher in mid-pregnancy in women who later experience the development of preeclampsia [19]. Similarly, in our cohort of high-risk pregnant women, office hypertension and 24 h, daytime, and nocturnal ABPM hypertension were associated with a greater risk for both late- and early-onset PE in nonadjusted regression models. However, when daytime and nocturnal hypertension were adjusted for BP values in the opposite situation (daytime hypertension by nocturnal BP and nocturnal hypertension by daytime BP), only nocturnal hypertension correlated with a higher risk for early-onset PE (Table 4, Model 2). Although nocturnal hypertension predicts both late- and early-onset PE, the risk was higher for the latter. Furthermore, when analyzed as continuous variables and adjusted for BP levels in the opposite period, systolic and diastolic nocturnal (but not daytime) ABPM predicted early-onset PE. Interestingly, isolated nocturnal hypertension (high BP during nocturnal rest with normal awake BP) was a significant predictor of late and early-onset PE. Conversely, isolated daytime hypertension was an uncommon and low-risk condition.

PE is a disease affecting two individuals: the mother and the fetus. Careful monitoring of the maternal condition and timely delivery explain the dramatic reduction in maternal mortality in the mid-20th century [3, 4]. Nonetheless, despite this approach, a considerable fetal burden persists. In a study in Washington State including more than 450,000 deliveries, early- but not late-onset PE conferred a high risk of fetal death (adjusted OR, 5.8; 95%CI 4.0–8.3 vs. adjusted OR, 1.3; 95%CI, 0.8–2.0, for early- and late-onset PE, respectively). Moreover, the OR for perinatal death or severe neonatal morbidity was 16.4 (95% CI, 14.5–18.6) in early-onset and 2.0 (95% CI, 1.8–2.3) in late-onset preeclampsia. As Table 1 shows, most of the perinatal disease in our cohort was due to early-onset PE; indeed, newborns of women with early-onset PE had lower birth weights and APGAR scores.

Regarding the long-term maternal consequences of both phenotypes, early-onset PE appears to be associated with more severe vascular disease. In a study with 30 years of follow-up, cumulative cardiovascular death survival was 85.9% for women with early-onset PE, 98.3% for women with late-onset PE and 99.3% for women without preeclampsia. Moreover, the relative risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease death was notably higher among those with onset of preeclampsia ≤34 weeks of gestation (hazard ratio: 9.54 [95% CI: 4.50 to 20.26]) [20]. Although the mechanism of the increased long-term cardiovascular risk in women who had PE has not been fully elucidated, it is reasonable to hypothesize that subclinical vascular dysfunction might precede the increase in cardiovascular events observed in women with the antecedent of early-onset PE. This possibility is supported by some evidence that women with early-onset PE may have diastolic dysfunction [21], altered elastic properties of the ascending aorta [22] and a radial augmentation index increase [23]. Furthermore, Christensen et al. showed that subclinical indices of atherosclerosis were higher in women who had early-onset PE than in those with late-onset PE at 12 years after the index pregnancy [24]. We hypothesize that nocturnal hypertension may be a link between early-onset PE and the increase in cardiovascular disease risk years after delivery.

The reasons for the relationships between nocturnal hypertension and PE are poorly understood, but several mechanisms may be responsible. First, elevated BMI may be associated with an increased severity of PE. Sattar and Green [25] suggested that metabolic changes during pregnancy might trigger PE in women with pre-existing subclinical risk factors (such as insulin resistance or endothelial dysfunction). In addition, the presence of abnormal upper airway resistance, particularly during sleep [26], may contribute to nocturnal BP alterations. However, in our cohort, women who developed early-onset PE did not have more obesity (Table 1). Second, vascular endothelial abnormalities are recognized as a central process in PE. Bouchlariotou et al. provided evidence that these markers of endothelial dysfunction are elevated in women with PE and nocturnal hypertension [27]. Finally, mechanisms associated with nocturnal hypertension, such as alteration in sympathetic tone and inadequate renal sodium handling during the nighttime, may be related to the development of PE [28].

Although the results of our study are straightforward, there are certain limitations that must be addressed. First, this study was performed on a cohort of high-risk pregnant women, and therefore, our findings are not necessarily applicable to normal pregnancies. Indeed, the high prevalence of PE observed might be explained by selection bias. Second, the diagnosis of hypertension by ABPM was achieved using the same threshold as for the general population. However, a recently published study of at-risk pregnant women in a southern Chinese population defined similar ABPM thresholds using a maternal and fetal outcome-derived approach [29]. The cutoff point used to define early-onset PE is arbitrary, but in an analysis of 1700 cases of PE, different cutoffs (from 30 to 37 weeks of gestation) were tested to define early- vs. late-onset PE, and the standard week 34 of gestation appears to provide a reasonable cutoff point [30]. Finally, the use of low doses of aspirin, calcium supplements, or antihypertensive drugs may influence the results. However, as Table 4 shows, the OR values were not altered by adjustment for antihypertensive drug, aspirin, and calcium supplement treatments.

In conclusion, nocturnal hypertension was the most frequent BP abnormality in high-risk pregnancies, effectively predicted early-onset PE and, consequently, helped to identify pregnancies with high fetal risk. Furthermore, early-onset PE is not likely in the absence of nocturnal hypertension. Thus, ABPM is a simple, noninvasive and available method to identify women at risk of developing more severe forms of PE, supporting the notion that it should be mandatory in high-risk pregnancies [11, 12].

References

Wildman K, Bouvier-Colle MH, MOMS Group. Maternal mortality as an indicator of obstetric care in Europe. BJOG. 2004;111:164–9.

Bakker R, Steegers EA, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW. Blood pressure in different gestational trimesters, fetal growth, and the risk of adverse birth outcomes: the generation R study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:797–806.

Saucedo M, Deneux-Tharaux C, Bouvier-Colle MH. Ten years of confidential inquiries into maternal deaths in France, 1998–2007. French National Experts Committee on Maternal Mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:752–60.

Schneider S, Freerksen N, Maul H, Roehrig S, Fischer B, Hoeft B. Risk groups and maternal-neonatal complications of preeclampsia-current results from the national German Perinatal Quality Registry. J Perinat Med. 2011;39:257–65.

Ness RB, Roberts JM. Heterogeneous causes constituting the single syndrome of preeclampsia: a hypothesis and its implications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1365–70.

Burton GJ, Redman CW, Roberts JM, Moffett A. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology and clinical implications. BMJ. 2019;366:I2381.

Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Incidence of preeclampsia: risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:544.e1–544.e12.

Salazar MR, Espeche WG, Leiva Sisnieguez BC, Balbín E, Leiva Sisnieguez CE, Stavile RN, et al. Significance of masked and nocturnal hypertension in normotensive women coursing a high-risk pregnancy. J Hypertens. 2016;34:2248–52.

Salazar MR, Espeche WG, Leiva Sisnieguez CE, Leiva Sisnieguez BC, Balbín E, Stavile RN, et al. Nocturnal hypertension in high-risk mid-pregnancies predict the development of preeclampsia/eclampsia. J Hypertens. 2019;37:182–6.

Salazar MR, Espeche WG, Balbín E, Leiva Sisnieguez CE, Leiva Sisnieguez BC, Stavile RN, et al. Office blood pressure values and the necessity of out-of-office measurements in high-risk pregnancies. J Hypertens. 2019;37:1838–1844.

Bilo G, Parati G. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: a mandatory approach in high-risk pregnancy? J Hypertens. 2016;34:2140–2.

Webster J. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in pregnancy: a better guide to risk assessment? J Hypertens. 2019;37:13–15.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36:1953–2041.

Li Y, Staessen JA, Lu L, Li LH, Wang GL, Wang JG. Is isolated nocturnal hypertension a novel clinical entity? Findings from a Chinese population study. Hypertension. 2007;50:333–9.

Li Y, Wang JG. Isolated nocturnal hypertension: a disease masked in the dark. Hypertension. 2013;61:278–83.

Tranquilli AL, Brown MA, Zeeman GG, Dekker G, Sibai BM. The definition of severe and early-onset preeclampsia. Statements from the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). Pregnancy Hypertens. 2013;3:44–7.

Kim JH. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72:558–69.

Brown MA, Davis GK, McHugh L. The prevalence and clinical significance of nocturnal hypertension in pregnancy. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1437–44.

Brown MA, Bowyer L, McHugh L, Davis GK, Mangos GJ, Jones M. Twenty-four-hour automated blood pressure monitoring as a predictor of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:618–22.

Mongraw-Chaffin ML, Cirillo PM, Cohn BA. Preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease death: prospective evidence from the child health and development studies cohort. Hypertension. 2010;56:166–71.

Melchiorre K, Sutherland GR, Liberati M, Thilaganathan B. Preeclampsia is associated with persistent postpartum cardiovascular impairment. Hypertension. 2011;58:709–15.

Orabona R, Sciatti E, Vizzardi E, Bonadei I, Valcamonico A, Metra M, et al. Elastic properties of ascending aorta in women with previous pregnancy complicated by early- or late-onset pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:316–23.

Yinon Y, Kingdom JC, Odutayo A, Moineddin R, Drewlo S, Lai V, et al. Vascular dysfunction in women with a history of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction: insights into future vascular risk. Circulation. 2010;122:1846–53.

Christensen M, Kronborg CS, Carlsen RK, Eldrup N, Knudsen UB. Early gestational age at preeclampsia onset is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis 12 years after delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:1084–92.

Sattar N, Greer IA. Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovascular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ. 2002;325:157–60.

Poyares D, Guilleminault C, Hachul H, Fujita L, Takaoka S, Tufik S, et al. Pre-eclampsia and nasal CPAP: part 2. Hypertension during pregnancy, chronic snoring, and early nasal CPAP intervention. Sleep Med. 2007;9:15–21.

Bouchlariotou S, Liakopoulos V, Dovas S, Giannopoulou M, Kiropoulos T, Zarogiannis S, et al. Nocturnal hypertension is associated with an exacerbation of the endothelial damage in preeclampsia. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:424–30.

Cuspidi C, Sala C, Tadic M, Gherbesi E, De Giorgi A, Grassi G, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of a reverse dipping pattern on ambulatory monitoring: an updated review. J Clin Hypertens. 2017;19:713–21.

Lv LJ, Ji WJ, Wu LL, Miao J, Wen JY, Lei Q, et al. Thresholds for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring based on maternal and neonatal outcomes in late pregnancy in a southern Chinese population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012027.

Robillard PY, Dekker G, Scioscia M, Bonsante F, Iacobelli S, Boukerrou M, et al. Validation of the 34-week gestation as definition of late onset preeclampsia: Testing different cutoffs from 30 to 37 weeks on a population-based cohort of 1700 preeclamptics. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:1181–90.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Luz Salazar Landea and Prof. María Carolina Ferrari for the final English corrections. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salazar, M.R., Espeche, W.G., Leiva Sisnieguez, C.E. et al. Nocturnal hypertension and risk of developing early-onset preeclampsia in high-risk pregnancies. Hypertens Res 44, 1633–1640 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00740-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00740-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Nocturnal systolic and diastolic blood pressure across gestational periods and the risk of preeclampsia

Journal of Human Hypertension (2025)

-

Hypertension phenotypes and adverse pregnancy outcome-related office and ambulatory blood pressure thresholds during pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study

Hypertension Research (2025)

-

Pulse wave velocity in high-risk pregnant women who subsequently developed early- and late-onset preeclampsia

Journal of Human Hypertension (2025)

-

Placental hypoxia, high nighttime blood pressure, and maternal health

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

More need to optimize the prediction model of sFlt- 1/PIGF ratio and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in preeclampsia

Hypertension Research (2024)