Abstract

Penile cancer is a rare malignancy (0.5–0.93/100,000 in Western countries) with significant psychosocial and sexual repercussions. This qualitative study explored the impact of penile cancer diagnosis and treatment on intimacy. A convenience sample was identified of 20 potential candidates who were at least 5 months post penile cancer surgery at a hospital centralizing penile cancer care. Participants were recruited by telephone and admitted until data saturation was reached, resulting in a sample of nine men (44–74 years old), none withdrew from participation. All interviews were performed by the same female researcher with no prior relationship to the men. The one-time interviews (35–61 min) followed a semi-structured interview guide, were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three researchers analysed the data independently using descriptive phenomenological analysis, resulting in a gradually drawn up coding tree mapping out the patient’s journey. The central themes that emerged were: (1) Intimate area led to diagnostic delays, intensified diagnosis and induced secrecy; (2) Impact on sexuality prior to surgery; (3) The voyage of sexual re-discovery; (4) A partnered voyage of sexual discovery; (5) Care needs related to intimate area. This study highlights the need for comprehensive and personalized care, including pre-surgical information provision and post-surgical psychosexual support. Addressing the current unmet needs of men with penile cancer requires guidelines for psychosexual interventions and proactive efforts to reduce stigma and to raise awareness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Penile cancer is a rare malignity with an incidence of 0.5–0.93 per 100,000 in Western countries and higher rates in the developing world [1]. Incidence increases with age, peaking in the sixth and seventh decade, but it also affects younger patients [2]. Most penile cancers are squamous cell carcinoma presenting with visible or palpable penile lesions. The lesions either arise de novo as an invasive carcinoma or progress from premalignant lesions. The lesion’s appearance ranges from painless ulcers, erythema, and hard lumps, to wart-like, exophytic aspects. Associated symptoms might be important for the diagnosis and include bleeding, discharge, foul odor or pain [3].

Surgery remains the cornerstone for the management of primary tumors, aiming to preserve as much organ as possible with as much radicality as necessary [4]. To maximize organ preservation, minimal safety margins are justified as recurrence has minimal impact on long-term survival [5]. In the early stages of the disease, local radiotherapy can be used, while the outcomes in cases of lymphogenic metastasis can improve with radical lymphadenectomy and adjuvant chemo- and radiotherapy [4]. The prognosis mainly depends on the presence and treatment of regional or distant extension [6]. The 5-year cancer-specific survival rates decrease progressively: ~95% for N0 disease, 80% for N1, 65% for N2, and 35% for N3 disease [7].

Despite the advances in treatment, the rarity and social stigma of penile cancer often leads to delays in diagnosis and treatment by both doctors and patients, causing hazardous consequences [8, 9]. Although penile cancer is curable in nearly 80% of cases, the implications of surgical treatment can be severe. These implications include significant aesthetic and functional challenges, such as voiding problems, limitations in mobility, pain, sexual dysfunction and lymphoedema, all of which majorly impact the quality of life [10,11,12,13]. The diagnosis of cancer, coupled with the potentially mutilating treatment outcomes, may cause feelings of sorrow and anxiety [11, 14], embarrassment and stigma [8, 15] and an altered perception of body image and identity [10, 12]. These issues result in a considerable psychological burden and create a need for psychosocial care [8, 10,11,12, 14, 15]. Therefore, support and counselling addressing physical, psychological, sexual, and social challenges should be systematically integrated into the care pathway for penile cancer [16]. However, specific implementation strategies remain to be clearly defined.

In addition to these challenges, penile cancer uniquely impacts sexuality and intimacy, and related problems might adversely affect quality of life [8]. Above mentioned treatments often affect sexual function, with up to two-thirds of patients [14, 17, 18] experiencing decreased function following partial penectomy [19,20,21]. While sexual function is an important aspect of intimacy, other aspects such as self-image, masculinity, libido, non-coital sexual practices and partner intimacy, may be equally important for penile cancer patients [22]. Previous studies have broadly focussed on ‘life as a whole’ addressing interpersonal needs [8, 9, 13, 15, 23], self-image and masculinity [24], with some emphasizing the sexual aspect of intimacy [25, 26]. Interestingly, despite intimacy being the most frequently mentioned care need [27], there is a lack of qualitative, in-depth research on all aspects of intimacy in penile cancer patients.

The present study aims to explore the impact of the diagnosis and treatment of penile cancer on intimacy. An attempt was made to gain further insight into the interpersonal needs of patients, specifically regarding self-image, masculinity, libido, sexual dysfunction and partner intimacy. The findings of this study may help healthcare providers enhance and promote individualized patient care, by optimising counselling practices based on the specific needs of patients.

Methods

Design

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in a single session to compare patients’ experiences regarding the impact of a penile cancer diagnosis and treatment on their intimacy. This method of interviewing offered the possibility to delve deeper into the meaning of individual answers, while avoiding the burden of multiple contacts with researchers. It also provides an exploration of thoughts, perspectives, and experiences of patients after penile cancer treatment, as they were given the freedom to fully express themselves. The individual interviews offered a private setting for participants to discuss penile cancer and sexuality, acknowledging the possible sensitivity of the topic.

Descriptive phenomenology was used to explore the patients’ lived experiences and to look for features that are commonly perceived in order to develop a generalisable description of the essence [28]. A phenomenological approach offered the possibility to learn from patient’s experience of penile cancer and its impact on intimacy, both in terms of what they experienced and how they experienced it [29].

Study population

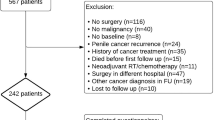

We identified a convenience sample of twenty potential candidates at least 5 months post-penile cancer surgery to ensure full recovery after treatment and to provide the time needed to assess the impact of the disease. Inclusion criteria included being over 18 years old, experiencing some form of sexuality, being able to understand the information letter and give written informed consent. An attempt was made to include patients up to 75 years old first, because sexuality may have a different role for older men. The recruitment and explanation of research objectives were done by telephone. Patients were admitted until data saturation was reached [30]. In total 10 men were recruited for participation. One man declined participation because he wanted to leave that part of his life behind. As a result, the final sample consisted of 9 participants who were interviewed, none of them withdrew from participation.

Data collection

The interview guide included seven essay questions: one related to the impact of penile cancer diagnosis on general well-being and six related to sexuality. Additionally, a topic list was created including relationship status, self-confidence, male identity, disfigurement, libido, sexual dysfunction, intimacy, satisfaction and lymphoedema. The interview also included background questions on the moment of diagnosis, delay, awareness, support and secrecy. A standardized introductory and closing text were used, with the opportunity to raise comments or to ask questions. The interview guide was not pilot tested.

All interviews were performed by the same inexperienced female researcher, a full-time master student of medicine doing her clinical clerkship at the time. There was no relationship established with the participants prior to the study. The interview could only proceed if the participant approved his participation, signed the informed consent form, and agreed to the audio recording. The first two interviews occurred in a meeting room at the Urology department. Due to of the corona pandemic, it was necessary to conduct the remaining interviews by telephone. In two interviews, the partner was present and had a limited input on the conversation. No field notes were made during or after the interviews.

Data analysis

The interviews (35–61 min) were audio-recorded, stored in an encrypted form and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not returned to participants for correction or comment. The descriptive phenomenological psychological method of Giorgi [31] was used for data analysis with the aim of describing the lived experience of a phenomenon and to clarify its meaning, without explaining nor discovering causes [32].

The content of the interviews was reviewed and coded using NVIVO by two independent coders, including the interviewer and a PhD, MSc, RM researcher experienced in qualitative research. A third researcher conducted the final review to ensure reliability. Transcripts were organized into meaningful units. Units with the same theme were then grouped into higher-level categories and given a code. New data were continuously used to expand previously existing categories or to create additional categories. This process resulted in a coding tree which was gradually drawn up as different themes were addressed. Researchers set aside past knowledge, beliefs and suppositions [28, 32] to accurately describe and compare data associated with each code and map out the patient’s journey. The theoretical saturation level was reached when no new themes emerged from the transcripts or when further data no longer provided added value.

Results

The nine participating men were all Caucasian and married or in a heterosexual relationship since diagnosis. None of the men withdrew from participation. Patient characteristics presented in Table 1.

Intimate area led to diagnostic delays

All but one man disregarded local symptoms for several months, despite the disruption they often caused to their sex life. They delayed seeking medical attention due to perceptions of the condition as trivial or embarrassment over intimate issues. One man delayed due to fear of cancer and reluctance to discuss a past sexually transmitted disease with his wife. Men finally consulted a physician when the symptoms could no longer be ignored.

‘I had a bleeding and I had an injury on my penis that had been there for a while but of which I thought… I did not know what it was, but I thought it could be an infection. But that was of course a way of hiding my head under the sand, like an ostrich.’ (Patient 6)

Intimate area led to intensified diagnosis

The subsequent diagnosis caused anxiety in seven men, due to fears of a life-threatening disease, concerns about their most intimate body part being the focus of attention and worries about potential mutilation.

‘My world stopped turning, I mean, I was digesting that I had cancer and he [the doctor] immediately talked about amputation. That was very, very difficult.’ (Patient 8)

Intimate diagnosis induced secrecy

Men informed their partner and a few exceptionally close others on the penile location of the cancer, often due to the need for surgery and hospitalisation. Only two men shared their exact diagnosis with a group of colleagues or friends. Secrecy was mainly driven by the desire to protect themselves or their partners from embarrassment and stigma associated with the condition. The need for discretion was reinforced by the rarity of penile cancer and its association with sexually transmitted diseases.

‘I decided not to inform others on the exact diagnosis as I did not want to be seen as the man without a penis, if I were to walk on the streets afterwards.’ (Patient 6)

Impact on sexuality prior to surgery

Five of the men did not experience any sexual inhibition prior to diagnosis, but two of them did experience some hinderance due to their symptoms. The four others were less into sex because of pain (n = 3) and the looks of their penis (n = 1).

‘You are confronted with a little wound and you think that it will heal if you are careful. You are a bit inhibited too as it is not a pretty sight. If it is not easy on the eye, than you are, of course, not into having sex.’ (Patient 9)

Most men experienced a reduction or complete cessation of sexual activity, whether solo or with a partner, in the 1–3 weeks between diagnosis and surgery. This was due to the local symptoms leading to the diagnosis, discomfort resulting from a biopsy or because they were simply not interested in sex during this period.

‘Sex is as far off of being top of your mind in that period, no need to act tough about that.’ (Patient 7)

Preparing for the loss

Whilst preparing for surgery men focussed on survival and accepted that this would require losing at least a part of their penis.

‘So at that moment [prior to surgery] I was almost like, if they take my thing off, so be it.’ (Patient 8)

They were, nevertheless, very anxious about what would be left of their penis post-surgery.

‘I panicked, I could not imagine what the end result would look like. The doctor had explained the different possibilities, showed pictures of the end result of other men. But I was nevertheless panicking.’ (Patient 9)

The voyage of sexual re-discovery

Making sense of the loss

After surgery, men mourned the changed looks of their penis.

‘Something has been taken from me, cut off. Yes, it is no longer as before, and it does not look as it did.’ (Patient 3)

Seven men discussed the impact of diagnosis and treatment on their male identity. Four of them shared that their male identity was affected while the three others contradicted. The differences in perspectives could not be explained by the extend of amputation.

‘I no longer felt like a man, I still struggle with that […] Every single time that you have a wee, so to say, you are confronted with it.’ (Patient 8, total penectomy and perineostomy)

‘I can no longer do certain things. Okay, that is that. But this does not affect my masculinity or my view on being a man, not at all. I still feel like a man, the same man. Masculinity does not depend on the few centimetres that have been cut off.’ (Patient 6, total penectomy and perineostomy)

Getting used to changed intimate parts

Before considering sex post-surgery, men’s wounds had to heal.

‘You are first occupied by the physical inhibitions, like wounds on the body parts which are most central in your sex life.’ (Patient 6)

Men had to gradually get used to their changed intimate parts. A first step was discovering morning erections or physical reactions to sexual stimuli. Patient 1 (total penectomy) shared how the hardening in his genital zone surprised him:

‘Yes, how is that possible? I have been feeling this for a while now. And I have told my son in law, I do get an erection now and then.’

Getting used to changed sexual experiences

Practically all men reported less sensitivity:

‘I feel a lot less during [sex]. And, well it is, so to say, a totally different feeling compared to what I used to feel.’ (Patient 3).

Two men believed that the loss of sensitivity resulted from lymphedema in addition to scars. One man, who had glans surgery without glansectomy and lymphadenectomy, explicitly said that he did not experience loss of sensitivity.

Seven men had experienced orgasms since their surgery. Three of these men who had glans surgery reached orgasms quickly during one of the first attempts. Two of them shared that it felt as good as before surgery, while one other man said it felt less intense. Another man, who had a partial penectomy, shared that after a learning curve his orgasm at the time of the interview, 15 years later, felt as good as they did before surgery. The three other men differing in surgery (glansectomy, partial/total penectomy) and time since surgery (4 months-2,3 years) shared that orgasming took a while and was still challenging. Patient 6, who was able to orgasm after his total penectomy shared:

‘Is it still possible to reach an orgasm, yes. But that is of course, we had to work hard for that, if I may say so, that is obvious. It is still possible but I must say that it is rare.’

The differences in experience and quality of orgasms could not be explained by the extent of surgery. However, the two men who had not reached orgasm at the time of the interview had undergone the most extensive treatment, a total penectomy with perineostomy. Due to unchanged arousal, the inability to reach orgasm caused frustration for these men.

‘I do get in the mood for sex but the only problem I have, is frustration, damn, I cannot orgasm.’ (Patient 8)

A partnered voyage of sexual discovery

Opening up to a partner

Before attempting partner sex, several men felt vulnerable and had to overcome embarrassment and fears. For several men, however, romantic partners were integral to rediscovering their sexuality. Adjusting to the changed body took time for men as well as their partners, with a crucial step in sexual rediscovery being giving partners permission to touch their genitals again.

‘And at that certain moment in time I told her that it was ok, that it did not hurt any more. At the very start I had been like, it can still hurt, I’d rather have her not touch it. But after a month or two the pain had eased down.’ (Patient 2)

One man discussed with his partner whether she would consider a sex life without a penis:

‘We did talk about it. I told her, if you cannot live without a man, without a penis, than I understand that you want to leave. But she said she did not need that.’ (Patient 8)

Satisfaction after treatment

Once getting over their initial embarrassment, four men shared that their sexual satisfaction was comparable to before diagnosis.

‘We have gotten over it, over that period of embarrassment and over it’s changed appearance. Our sexual experience is now back to what it used to be.’ (Patient 9)

Reframing intimacy after treatment

Men valued the ability to provide sexual pleasure to their partner and rediscovering how to do so was an important aspect of their sexuality. Two men, who had a partial and total penectomy, gradually prioritized intimacy over purely physical aspects of sex, ultimately finding reconciliation with this change.

‘Sex is always and for everyone a mix of something physical and of intimacy […] For me, there has been a clear shift towards intimacy […] I will focus on the good things and on what I can still do. In that respect, all you can experience and can give, is a step in the right direction. A step that, independently of orgasms, gives you satisfaction.’ (Patient 6)

However, two other men remained frustrated that partner sex was less satisfying after cancer. One man also worried about reactions from other women besides his wife.

‘I do ask myself, what if my wife would no longer be around and I meet someone new. How would that someone react to this? It might be a question that I should not be asking myself […] About sexual aspects, no, I still regret that. But what can I do. It was important to me and now it is as it is. I have to continue my life.’ (Patient 5)

The sexual dynamics were also influenced by sexual dysfunction and the age of the partner in two couples. The oldest man disclosed that although he could still engage in sexual activity, partner sexual activities had ceased before diagnosis when his wife had entered menopause.

Care needs related to intimate area

Pre-surgical information

Men felt stressed during the waiting period before consultations, wanting to know their results as soon as possible. Additionally, the presence of residents during consultations was challenging for two interviewed men.

‘Because you always get a student first, so to speak. And they then ask, sir, what are you here for? That I’m like did you even read my file? Come on, I just want to know if I have cancer or not.’ (Patient 8)

All men received preoperative information about the surgical plan from their physician. Whilst most desired more information on the surgery’s potential functional implications, one man feared it would have increased his stress afterwards.

Post-surgical information and support

Immediately post-surgery two men wanted more details on the exact procedure performed and its functional consequences, including reconstruction options.

‘But, we had thought, that operation is going to happen and then we might get the explanation of what happened, what was taken away and all that. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen.’ (Patient 2)

Two men discussed the support they received from nurses post-surgery in accepting their new penis. Patient 5 expressed how the daily care constantly confronted him with his new reality:

‘That’s a red stump sitting there. You do wonder how all this is going to be of any use here? How are you all going, how are you still going sexually, and so on? So I had a really hard time with that.’

Patient 8 felt reassured by the nurses’ care:

‘And especially the nursing staff, what they- I mean, really great job. - …- That those people came to wash me and stuff and reassured me.’

Psychosexual counselling

Six men recalled that a healthcare professional mentioned counseling as an option. Four men felt a need for psychosexual support, but two of them stated it was never offered. Despite being mentioned to most, only two men attended psychosexual counseling. One of them had to overcome his internal resistance to psychological counseling before attending. Ultimately, both men benefitted from the psychosexual support in their sexual rediscovery.

‘We were not going to do it [go to psychologist]. But then we did it anyway and we are glad we did.’ (Patient 2)

Besides professional support, men were interested in offering and receiving support from other survivors.

‘… if there are people who are confronted [with this disease], they can call me. -…- I can also support those people in some way.’ (Patient 7)

Discussion

This study explored the impact of penile cancer diagnosis and treatment on intimacy, focusing on the interpersonal needs of patients. To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth, qualitative study focusing on all aspects of intimacy during sexual rediscovery after penile cancer.

In line with Attalla et al. [33] we found that men were reluctant to seek help, due to the rarity of the disease, lack of awareness and psychosocial factors, which resulted in diagnostic delays. The need for secrecy was further reinforced because of the sensitive nature of the affected body part and concerns about mutilation. This lack of awareness and embarrassment could prolong the time to consult a professional by up to two years [9, 23]. Therefore, it is crucial to address the stigma associated with penile cancer and promote greater awareness among patients and healthcare providers. This will help facilitate earlier diagnosis and improve treatment outcomes [33].

In addition to common emotional responses such as shock, panic, anxiety, disbelief and fear of death (e.g., [8, 18, 24]), men also mourned the changed appearance of their penis after surgery. This change led to diminished self-confidence and an altered sense of masculinity in approximately half of the participants. The reduced penile length, along with challenges with urination and sexual activity, contributed to feelings of emasculation. The diagnosis and treatment of penile cancer challenges several traditional masculine ideals, such as physical strength and sexual potency. Men who strongly identify with these ideals may be more susceptible to changes in their experience of masculinity post-surgery [15, 24]. Furthermore, studies have shown associations between strong negative male sexual beliefs and sexual dysfunction in men [34].

Interestingly, we observed that while the extent of surgical intervention didn’t necessarily correlate with changes in masculinity, it did impact sexual satisfaction post-surgery. Our study corroborates previous research [15, 24] indicating that men experience changes in sensitivity and challenges reaching orgasm post-surgery, causing frustration in men with unchanged libido. The correlation between quality of life, degree of sexual dysfunction, and the invasiveness of treatment has been reported in several studies [12, 13, 20, 25]. We observed that younger patients with less extensive surgeries were more likely to have partner sex after surgery comparable to before surgery. In contrast, older patients or those with more extensive surgeries often transitioned towards intimacy and non-coital forms of sexual expression. While studies have shown that such a shift towards non-coital intimacy often occurs in aging adults [35, 36], facing penile cancer may accelerate this process. Shifting away from penetrative intercourse and embracing alternative forms of intimacy are considered important aspects of effective sexual rehabilitation after cancer [22].

In navigating the journey of sexual rediscovery, the support of intimate partners appears to play a crucial role. Studies have shown that partner support enhances men’s coping abilities [8, 13, 15] and facilitates successful sexual rehabilitation [24]. Additionally, having a partner with good sexual function may positively affect the sexual outcomes of patients [26]. Thus, future research into psycho-sexual interventions should include perspectives of partners and address the needs of men without partners, who may be more vulnerable to sexual difficulties.

To enhance the care pathway of penile cancer patients in the future, it is important to address their existing unmet needs. Consistent with prior studies [8, 13, 23, 37], men expressed a lack of pre-surgical information regarding the potential impact of penile surgery on their physical, psychological and sexual function and well-being. Moreover, there was an unmet demand for psychosexual support after surgery. Interestingly, contrary to prior studies [8, 13, 23] reporting that most men did not receive information about psychosexual counseling, most men in this study did receive this information from healthcare providers. Nevertheless, the majority did not engage in psychosexual counseling, suggesting internal resistance and other potential obstacles. These barriers that prevent patients from seeking psychosexual counseling should be addressed in future research. Despite existing literature documenting the impact of penile cancer on mental and sexual health (e.g., [8, 15, 25]), research on strategies to support patients in managing intimate and sexual challenges remains limited. Consequently, there is a clear need for evidence-based guidelines outlining effective psychosexual interventions tailored to this patient population.

Limitations and future research

Firstly, the study sample consisted of nine white men in a stable, heterosexual relationship, all recruited from a single specialist center. Due to homogeneity and small sample size, generalization of the results to a broader patient population is not feasible. Participants varied in age, cancer stage, and treatment, but the small sample size did not allow for any further subdivision. This small sample size, however, allowed for a more in-depth exploration of individual experiences. Future research could benefit from collaboration with multiple centers to include a larger, more diverse cohort, allowing for in-depth exploration of different cancer stages and treatment types.

Secondly, the one-time nature of the interviews limits the ability to capture changes in participants’ experiences over time. Longitudinal studies could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the evolving psychosocial impact of penile cancer.

Thirdly, the interviews were conducted by an female interviewer with limited experience, which may have increased the risk of socially desirable answers. Furthermore, a shift from in-person to remote phone interviews was necessary due to unforeseen circumstances. This may have affected participants’ comfort and the expression of non-verbal cues, though the impact on the results remains unclear.

Lastly, this study focused on the experience of men, with insights about their partners based solely on what the men reported about them. In two cases, the partner was actually present and, albeit limited, had an input in the conversation. However, the resulting dialogue created an open atmosphere in which the man was encouraged to speak, while the partner was able to add and correct information if necessary. The results suggest that partners play an important role in the sexual rediscovery after penile cancer. The role of the partner may be a key consideration for future research.

Conclusion

The journey of intimate rediscovery after penile cancer is complex and personal, requiring tailored psychosexual support for both men and their partners. This study highlights the need for comprehensive, personalized care that addresses potential functional and psychosexual challenges. To encourage discussion about these challenges, establishing a safe environment for open communication is crucial. Finally, proactive efforts to raise awareness for penile cancer are necessary to reduce stigma and embarrassment.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fu L, Tian T, Yao K, Chen X-F, Luo G, Gao Y, et al. Global pattern and trends in penile cancer incidence: population-based study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8:e34874.

Cancer Research UK. Penile cancer incidence trends by age. 2024. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/penile-cancer/incidence#heading-One.

Barocas DA, Chang SS. Penile cancer: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and staging. Urol Clin N Am. 2010;37:343–52.

Hakenberg OW, Dräger DL, Erbersdobler A, Naumann CM, Jünemann KP, Protzel C. The diagnosis and treatment of penile cancer. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:646–52.

Leijte JA, Kirrander P, Antonini N, Windahl T, Horenblas S. Recurrence patterns of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: recommendations for follow-up based on a two-centre analysis of 700 patients. Eur Urol. 2008;54:161–8.

Wen S, Ren W, Xue B, Fan Y, Jiang Y, Zeng C, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with penile cancer after surgical management. World J Urol. 2018;36:435–40.

Horenblas S, van Tinteren H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. IV. Prognostic factors of survival: analysis of tumor, nodes and metastasis classification system. J Urol. 1994;151:1239–43.

Gordon H, LoBiondo-Wood G, Malecha A. Penis cancer: the lived experience. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40:E30–E38.

Skeppner E, Windahl T, Andersson SO, Fugl-Meyer KS. Treatment-seeking, aspects of sexual activity and life satisfaction in men with laser-treated penile carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2008;54:631–9.

Draeger DL, Sievert KD, Hakenberg OW. Cross-sectional patient-reported outcome measuring of health-related quality of life with establishment of cancer- and treatment-specific functional and symptom scales in patients with penile cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16:e1215–e1220.

Dräger DL, Protzel C, Hakenberg OW. Identifying psychosocial distress and stressors using distress-screening instruments in patients with localized and advanced penile cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:605–9.

Kieffer JM, Djajadiningrat RS, van Muilekom EA, Graafland NM, Horenblas S, Aaronson NK. Quality of life for patients treated for penile cancer. J Urol. 2014;192:1105–10.

Witty K, Branney P, Evans J, Bullen K, White A, Eardley I. The impact of surgical treatment for penile cancer - patients’ perspectives. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:661–7.

Ficarra V, Righetti R, D’Amico A, Pilloni S, Balzarro M, Schiavone D, et al. General state of health and psychological well-being in patients after surgery for urological malignant neoplasms. Urol Int. 2000;65:130–4.

Bullen K, Matthews S, Edwards S, Marke V. Exploring men’s experiences of penile cancer surgery to improve rehabilitation. Nurs Times. 2009;105:20–4.

Törnävä M, Harju E, Vasarainen H, Pakarainen T, Perttilä I, Kaipia A. Men’s experiences of the impact of penile cancer surgery on their lives: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2022;31:e13548.

Maddineni SB, Lau MM, Sangar VK. Identifying the needs of penile cancer sufferers: a systematic review of the quality of life, psychosexual and psychosocial literature in penile cancer. BMC Urol. 2009;9:8.

D’Ancona CA, Botega NJ, De Moraes C, Lavoura NS Jr, Santos JK, Rodrigues Netto N Jr. Quality of life after partial penectomy for penile carcinoma. Urology 1997;50:593–6.

Yu C, Hequn C, Longfei L, Minfeng C, Zhi C, Feng Z, et al. Sexual function after partial penectomy: a prospectively study from China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21862.

Sansalone S, Silvani M, Leonardi R, Vespasiani G, Iacovelli V. Sexual outcomes after partial penectomy for penile cancer: results from a multi-institutional study. Asian J Androl. 2017;19:57–61.

Romero FR, Romero KR, Mattos MA, Garcia CR, Fernandes Rde C, Perez MD. Sexual function after partial penectomy for penile cancer. Urology 2005;66:1292–5.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, Wong WK, Hobbs K. Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:454–62.

Mortensen GL, Jakobsen JK. Patient perspectives on quality of life after penile cancer. Dan Med J 2013;60:A4655.

Bullen K, Edwards S, Marke V, Matthews S. Looking past the obvious: experiences of altered masculinity in penile cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:933–40.

Opjordsmoen S, Waehre H, Aass N, Fossa SD. Sexuality in patients treated for penile cancer: patients’ experience and doctors’ judgement. Br J Urol. 1994;73:554–60.

Skeppner E, Fugl-Meyer K. Dyadic aspects of sexual well-being in men with laser-treated penile carcinoma. Sex Med. 2015;3:67–75.

Paterson C, Primeau C, Bowker M, Jensen B, MacLennan S, Yuan Y, et al. What are the unmet supportive care needs of men affected by penile cancer? A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;48:101805.

Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8:90–7.

Teherani A, Martimianakis T, Stenfors-Hayes T, Wadhwa A, Varpio L. Choosing a qualitative research approach. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:669–70.

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893–907.

Giorgi A. The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. J Phenomenol Psychol. 2012;43:3–12.

Giorgi A. The phenomenological movement and research in the human sciences. Nurs Sci Q 2005;18:75–82.

Attalla K, Paulucci DJ, Blum K, Anastos H, Moses KA, Badani KK, et al. Demographic and socioeconomic predictors of treatment delays, pathologic stage, and survival among patients with penile cancer: a report from the National Cancer Database. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:14.e17–14.e24.

Moura CV, Vasconcelos PC, Carrito ML, Tavares IM, Teixeira PM, Nobre PJ. The role of men’s sexual beliefs on sexual function/dysfunction: a systematic review. J Sex Res. 2023;60:989–1003.

Müller B, Nienaber CA, Reis O, Kropp P, Meyer W. Sexuality and affection among elderly German men and women in long-term relationships: results of a prospective population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e111404.

Sandberg L. Just feeling a naked body close to you: men, sexuality and intimacy in later life. Sexualities. 2013;16:261–82.

Delaunay B, Soh PN, Delannes M, Riou O, Malavaud B, Moreno F, et al. Brachytherapy for penile cancer: efficacy and impact on sexual function. Brachytherapy 2014;13:380–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: LR, MA, and ED. Data acquisition: LR. Phenomenological analysis: LR, ED, and CR. Analysis and interpretation of data: LR, ED, and CR. Drafting of Manuscript: CR and ED. Critical revision of manuscript: CR, ED, and MA. Supervision: ED and MA. Approval of the final manuscript: ED, MA. Funding: N/A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Research Ethics Committee of UZ/KU Leuven. The study adhered to the Helsinki protocols and patients provided written, informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Roumieux, C., Royakkers, L., Albersen, M. et al. The impact of diagnosis and treatment of penile cancer on intimacy: a qualitative assessment. Int J Impot Res 37, 759–765 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-024-00992-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-024-00992-6

This article is cited by

-

Sexual functioning after penile cancer surgery: comparison between surgical approaches in a large patient cohort

International Journal of Impotence Research (2025)

-

“Sexuality in penile cancer: lessons learned and the road ahead”

International Journal of Impotence Research (2025)

-

“Penile cancer and sexuality: advancing care beyond oncological outcomes”

International Journal of Impotence Research (2025)

-

Penile cancer treatment and sexuality: a narrative review

International Journal of Impotence Research (2025)

-

Organerhalt oder Radikalität? Moderne chirurgische Konzepte im Spannungsfeld von Funktion und Onkologie

Die Urologie (2025)