Abstract

Urethral complications following urethral lengthening in transgender men, such as strictures and fistulas, are common and frequently necessitate secondary surgical interventions. These surgeries vary significantly in their techniques and are evaluated with considerable heterogeneity, making a synthesized presentation of their outcomes valuable for guiding clinical management. This systematic review included 14 studies selected through a database search (Medline, Embase, Web of Science) that reported urethral complications after urethral lengthening. Among the 595 patients considered, 76% underwent phalloplasty and 24% underwent metoidioplasty. Our findings highlight that staged urethroplasty techniques demonstrated the lowest recurrence rates (0–25%), particularly in the management of long strictures in the pendulous urethra. In contrast, one-stage urethroplasties—especially those performed without augmentation—were associated with high recurrence rates, reaching approximately 50%, even when buccal mucosa grafts were used for augmentation. Patient-reported outcomes were documented in only one-third of the included studies, underscoring the limited functional evaluation of urethroplasty outcomes following phalloplasty. The considerable variability in urethroplasty techniques, types of genital reconstruction, and reporting standards highlights the need for more comprehensive and standardized outcome assessments. Future studies will be essential in advancing our understanding and optimizing the management of these complex cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urethral lengthening (UL) is a possible component of total phallic construction (TPC) in transgender men [1], as the ability to void while standing is frequently identified as an important goal in masculinizing genital surgery [2]. However, UL is associated with both short and long-term complications, emphasizing the importance of lifelong follow-up for individuals who undergo this procedure [3]. These complications, which are indeed common, primarily include urethral strictures and fistulas [4], requiring additional surgeries in 30 to 50% of transgender men [5, 6] Additionally, such issues may coexist with other challenges, such as hair-bearing tissue within the urethra or the formation of diverticula, particularly in areas such as the residual vaginal cavity [7].

The surgical management of urethral complications in transgender men presents unique challenges. These arise from the absence of a corpus spongiosum to support the neourethra, the utilization of scarred or less elastic flap tissues with reduced healing capacities, and the frequent requirement for secondary surgeries to address associated complications [8]. Recent years have seen the development of treatment algorithms [9, 10] and guidelines [11] that aimed at standardizing the care of urethral strictures in transgender men, considering factors such as position or length of the stricture. However, the existing literature on this topic remains limited, particularly regarding studies that assess functional outcomes using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) [12]. Moreover, most reported techniques focus on stricture treatment, whereas the management of associated fistulas may require different therapeutic approaches [13]. In this systematic review, we aim to provide a comprehensive analysis of the outcomes of urethroplasty in transgender men, and discuss the recent treatment guidelines in light of reported clinical outcomes. This synthesis seeks to enhance understanding and inform surgical strategies for optimizing patient care in this population.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic search of the Medline, Embase and Web of Science database, with the last search performed in December 2024 (Supplementary file 1). The search was restricted to studies published in English. Additional relevant literature was identified by screening references cited in a recent literature review [12] and the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines 2024 on urethral strictures in transgender men [11]. The review was not previously registered in any database such as Prospero.

Eligibility and screening

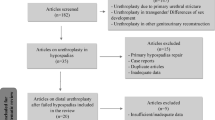

After removing duplicates and records that consisted only of abstracts, the remaining articles were independently screened by two reviewers (PN, FXM) to assess eligibility. The inclusion criteria, based on the PICO framework [14], included transgender men undergoing phalloplasty or metoidioplasty for TPC. The intervention was urethroplasty, while a control group was included if reported. Outcomes were those reported in the included studies, encompassing both anatomical and functional results. Studies were excluded if they lacked detailed outcomes, focused on non-surgical management, or reported solely on cisgender populations. Any disagreements during the screening process were resolved through discussion between reviewers (PN, FXM, NMJ). A PRISMA-compliant flowchart detailing the inclusion process, from the initial database search to the final selection of studies, was created to ensure transparency and adherence to systematic review guidelines [15]. A risk of bias evaluation was performed using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series [16].

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each included study:

-

1.

Demographic and Procedural Information: Population size, type of TPC (e.g., phalloplasty or metoidioplasty), and underlying indication for urethroplasty (e.g., urethral stricture or fistula).

-

2.

Surgical Techniques: Type of urethroplasty performed (e.g., augmentation urethroplasty, buccal mucosa graft (BMG), or staged procedures).

-

3.

Outcomes: Outcomes were categorized as patient-reported outcomes (e.g., satisfaction with voiding function or the use of validated or non-validated questionnaires) and objective outcomes (recurrence rates for strictures or fistulas).

-

4.

Follow-up: Duration of follow-up reported in months.

-

5.

Key Findings: Summary of notable results or conclusions from each study.

Data synthesis

The findings were synthesized and organized into a table that provided an overview of the key characteristics and outcomes for each study. Data were further grouped based on the type of urethral disease (stricture, fistula, or both) and type of reconstruction (phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, or both). The recurrence rate of complications was specifically highlighted, alongside patient-reported outcomes where available.

Results

Study selection

The systematic search identified 108 records from Medline®. A complementary search was conducted in the Embase and Web of Science databases, but no additional articles were identified. After automatically removing (duplicate, non-English articles), 96 records were screened. Of these, 78 articles were excluded due to irrelevance, including studies focused solely on cisgender men (n = 18), reviews (n = 11), and those without urethroplasty outcomes (n = 49). Eighteen reports were assessed for eligibility, and ultimately, 14 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. The study selection process is detailed in the PRISMA flowchart [15] (Fig. 1).

The 14 studies included represented diverse surgical approaches, patient populations, and urethral complications. A summary of study characteristics and key findings is presented in Table 1.

Study characteristics

The included studies involved a total of 595 patients undergoing urethroplasty, primarily following phalloplasty (n = 452, 76.0%, most commonly utilizing a radial forearm free flap) or metoidioplasty (n = 143, 24.0%). The majority of participants were transgender men, although a few studies also included cisgender men, albeit rarely (2.7%). Urethral strictures were the most frequently reported complications, with many studies also addressing fistulas and combined urethral issues. Follow-up durations varied significantly, ranging from 4 to 202 months, with the majority of studies reporting a mean follow-up period exceeding two years. The risk of bias analysis is reported in Table 2 [16]. A notable source of uncertainty across all included studies was the reliability of outcome measurements, particularly in assessing recurrence, which was largely defined by the absence of reintervention. This assessment may have been impacted by loss to follow-up, a limitation that is especially relevant in retrospective studies.

Surgical approaches and outcomes

To provide a clearer understanding of the outcomes from various studies, Fig. 2 presents an example of UL anatomy following phalloplasty, while Fig. 3 illustrates examples of urethral complications. Several urethroplasty techniques were employed across studies, including single-stage [9, 17, 18] and staged repairs [19, 20], buccal mucosa graft urethroplasty (BMGU) [7, 17, 21], excision and primary anastomosis (EPA) [22], pedicled flaps [23], Heineke-Mikulicz procedure (HMP) [23,24,25] and ventral meatotomy [26].

While one-stage repairs offer the advantage of fewer surgeries, they were associated with higher recurrence rates, particularly in cases involving poor tissue quality or extensive scar tissue [18, 20, 23, 24].

Staged urethroplasty consistently demonstrated lower recurrence rates, particularly in managing complex or long strictures, as shown in studies by Beamer et al. [18] and Schardein et al. [20], both of which utilized BMG for staged augmentation. Success rates (i.e., absence of recurrence) for staged procedures ranged from 100% to 75%, these procedures were often employed for longer and/or more complex strictures.

BMGU was effective for mid-length strictures but demonstrated recurrence rates as high as 50% in some cases [17].

In the only study comparing outcomes between the two techniques, success rates of urethroplasty were higher following metoidioplasty compared to phalloplasty [10]. Conversely, the highest recurrence rates were observed after urethroplasty performed on phalloplasty.

The techniques used for fistula repair were not described in detail, except for the mention of fistulectomy, which could be combined with more complex procedures such as redo-vaginectomy—though again, specific details of the surgical methods were not provided.

Patient-reported outcomes

PROs were included in only five studies [7, 18, 20, 21, 27], underscoring a notable gap in the functional evaluation of outcomes. Furthermore, the recurrence rate was consistently the sole criterion used for anatomical evaluation, indicating a need for broader and more comprehensive assessment criteria. High levels of satisfaction were reported with staged repairs and double-face BMGU [20, 21], particularly regarding restoration of upright voiding.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we analyzed a total of 585 urethroplasty procedures performed primarily in transmen, mostly following phalloplasty, with a smaller number occurring after metoidioplasty. In rare instances, outcomes of urethroplasty in cisgender men were included in the reported data. The urethra in phalloplasty is often constructed using a combination of local mucosal flaps for the pars fixa and skin flaps or grafts for the pars pendulans, creating a structure composed of different types with varying supportive tissues and healing capacities. The urethra in metoidioplasty is often constructed using a combination of local mucosal flaps, with adjunction of BMG or vaginal mucosa graft; this approach closely resembles the construction of the pars fixa in phalloplasty. The main complications arise from the distal urethral anastomosis and the pars pendulans, where skin is commonly used. In contrast, BMG is the preferred graft material for redo urethroplasty [28].

Our findings underscore that staged urethroplasty techniques demonstrated the lowest recurrence rates, with this approach predominantly reported for managing long strictures in the pendulous urethra. Conversely, one-stage urethroplasty, especially when performed without augmentation (e.g., HMP or end-to-end anastomosis), was associated with high recurrence rates, reaching approximately 50%. Even with augmentation BMGU, recurrence rates remained notable and significantly higher than those reported for urethroplasty in cisgender patients.

PROs were reported in only a third of the included studies, highlighting the lack of a functional evaluation in urethroplasty outcomes after phalloplasty. The PROs varied across the five studies that incorporated them, ranging from the ability to void while standing to questionnaires assessing urinary symptoms or perceived improvement after surgery, using a mix of ad-hoc and validated questionnaires. This variability made it challenging to synthesize the findings in a cohesive manner. The definition of success in urethroplasty and the standardized criteria for its evaluation remain subjects of ongoing debate, notably in the context of cisgender men [29, 30]. However, there is consensus that a comprehensive assessment should encompass both anatomical and functional outcomes [31,32,33]. Sole reliance on recurrence rates offers a limited perspective on anatomical success [29], particularly in retrospective studies, which comprised the entirety of the studies included in this review. Future studies are encouraged to report both functional and anatomical success using more robust and standardized criteria, as suggested by various guidelines on urethroplasty in cisgender men [28, 33, 34].

The EAU guidelines on urethral stricture have included a dedicated section for transgender men since their initial publication [11]. In the latest version, the recommendations are limited to delaying urethroplasty for at least six months following phalloplasty, and favoring staged urethroplasty for strictures in the neophallus urethra. This preference is supported by consistently high patency rates observed across studies using staged technique. However, the lack of robust evidence in the available studies limits the recommendation to a “weak” strength.

One-stage, non-augmented procedures such as HMP or EPA are mentioned as options, primarily for strictures located at the distal urethra anastomosis (pars fixa–pars pendulans anastomosis) [28]. Despite this, these techniques are associated with high recurrence rates and are not included as formal recommendations. Their use may be limited to short (<1.5 cm), non-complex strictures, as outlined in a recent disease management algorithm [10].

Our review has several limitations, the most significant being the risk of bias across the included studies. Notably, all the studies were retrospective in nature, lacking predefined protocols or prespecified outcomes of interest. Additionally, missing data were not consistently reported or adequately explained, which can have a considerable impact, especially in retrospective studies with relatively small sample sizes. Another limitation lies in the inherent complexity of phalloplasty reconstruction, which introduces substantial variability in the anatomy of the reconstructed urethra [35]. Additional variability can arise from the inclusion of peritoneal grafts [36] reinforcement with a pedicled gracilis flap [37], or the impact of an associated colpectomy [38], further contributing to the complexity of the reconstructed urethra. While this variability is less pronounced, it is still present in cisgender men, where differences in supporting tissue and vascularization are observed between the penile, bulbar, and prostatic urethra. Differences may allowpr for alternative techniques for urethroplasty, as urethral closure under suprapubic tunnel or abdominal pedicled skin flap which have recently been described in cismen [39]. The predominance of transgender men in the studies did not allow for comparison despite anatomical differences. Conversely, urethroplasty outcomes clearly differ between metoidioplasty and phalloplasty, as highlighted in the study by De Rooij et al. [10] These differences underscore the importance of reporting outcomes for these procedures separately to ensure accurate and meaningful comparisons. Another source of variability in phalloplasty reconstruction lies in the urethral environment. Factors such as vaginal remnants or mucoceles, hair-bearing urethra, and the presence of urinary stones are relatively common in some cohorts [7, 18] but are infrequently reported across studies. These factors introduce significant potential for confounding bias in the analysis of urethroplasty outcomes, further complicating the interpretation of results.

Further studies are encouraged to improve the analysis of outcomes following urethroplasty after phalloplasty, as a more comprehensive understanding is crucial for advancing patient care. In this context, it is important that outcomes are reported and analyzed with attention to key factors such as stricture length, location, the type of tissue comprising the urethra at the stricture site, associated complications, and the urethroplasty techniques utilized. As highlighted earlier, the assessment of outcomes should include both functional and anatomical evaluations to accurately measure the success of this complex procedure. A multi-institutional study is currently being developed by the YAU–EAU Reconstructive Group (Phalloplasty-Associated Neourethral Treatment for Strictures, PANTS Study), and aim to provide a more comprehensive understanding of this complex procedure.

Conclusion

This review highlights the complexity of urethroplasty after phalloplasty, with staged techniques showing lower recurrence rates compared to one-stage procedures. Variability in reconstruction methods, tissue composition, and reporting standards underscores the need for more comprehensive and standardized outcome analyses. Future studies, such as the ongoing PANTS Study by the YAU–EAU Reconstructive Group, are essential to improve our understanding and management of these challenging cases.

References

Walton AB, Hellstrom WJG, Garcia MM. Options for Masculinizing Genital Gender Affirming Surgery: A Critical Review of the Literature and Perspectives for Future Directions. Sex Med Rev. 2021;9:605–18.

Ganor O, Taghinia AH, Diamond DA, Boskey ER. Piloting a Genital Affirmation Surgical Priorities Scale for Trans Masculine Patients. Transgender Health. 2019;4:270–6.

Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, Brown GR, de Vries ALC, Deutsch MB, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 2022;23:S1–S259.

Ortengren CD, Blasdel G, Damiano EA, Scalia PD, Morgan TS, Bagley P, et al. Urethral outcomes in metoidioplasty and phalloplasty gender affirming surgery (MaPGAS) and vaginectomy: a systematic review. Transl Androl Urol. 2022;11:1762–70.

Hu C-H, Chang C-J, Wang S-W, Chang K-V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of urethral complications and outcomes in transgender men. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg JPRAS 2021: S1748-6815(21)00384–3.

Waterschoot M, Hoebeke P, Verla W, Spinoit A-F, Waterloos M, Sinatti C, et al. Urethral Complications After Metoidioplasty for Genital Gender Affirming Surgery. J Sex Med. 2021;18:1271–9.

Paganelli L, Morel-Journel N, Carnicelli D, Ruffion A, Boucher F, Maucort-Boulch D, et al. Determining the outcomes of urethral construction in phalloplasty. BJU Int. 2023;131:357–66.

Santucci RA. Urethral Complications After Transgender Phalloplasty: Strategies to Treat Them and Minimize Their Occurrence. Clin Anat N.Y. 2018;31:187–90.

Lumen N, Monstrey S, Goessaert A-S, Oosterlinck W, Hoebeke P. Urethroplasty for strictures after phallic reconstruction: a single-institution experience. Eur Urol. 2011;60:150–8.

de Rooij F, Peters F, Ronkes B, van der Sluis W, Al-Tamimi M, van Moorselaar R, et al. Surgical outcomes and proposal for a treatment algorithm for urethral strictures in transgender men. BJU Int. 2022;129:63–71.

Riechardt S, Waterloos M, Lumen N, Campos-Juanatey F, Dimitropoulos K, Martins FE, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Urethral Stricture Disease Part 3: Management of Strictures in Females and Transgender Patients. Eur Urol Focus. 2021. S2405-4569(21)00193–0.

Verla W, Lumen N, Waterloos M, Adamowicz J, Campos-Juanatey F, Cocci A, et al. Treatment of anastomotic strictures after phalloplasty: An up-to-date review of the literature. Actas Urol Esp Engl Ed. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acuroe.2024.11.001.

Fascelli M, Sajadi KP, Dugi DD, Dy GW. Urinary symptoms after genital gender-affirming penile construction, urethral lengthening and vaginectomy. Transl Androl Urol. 2023;12:932–43.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2007;7:16.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009; 6 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:123–8.

Pariser JJ, Cohn JA, Gottlieb LJ, Bales GT. Buccal Mucosal Graft Urethroplasty for the Treatment of Urethral Stricture in the Neophallus. Urology. 2015;85:927–31.

Beamer MR, Schardein J, Shakir N, Jun MS, Bluebond-Langner R, Zhao LC, et al. One or Two Stage Buccal Augmented Urethroplasty has a High Success Rate in Treating Post Phalloplasty Anastomotic Urethral Stricture. Urology. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2021.05.045.

Rohrmann D, Jakse G. Urethroplasty in Female-to-Male Transsexuals. Eur Urol. 2003;44:611–4.

Schardein J, Beamer M, Kittleman MA, Nikolavsky D Staged Urethroplasty for Repairs of Long Complex Pendulous Strictures of a Neophallic Urethra. Urology 2022; S0090-4295(22)00075–9.

Schardein J, Beamer M, Hughes M, Dmitriy N. Single-Stage Double-Face Buccal Mucosal Graft Urethroplasty for Neophallus Anastomotic Strictures. Urology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.06.010.

Verla W, Hoebeke P, Spinoit A-F, Waterloos M, Monstrey S, Lumen N Excision and Primary Anastomosis for Isolated, Short, Anastomotic Strictures in Transmen. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020; 8. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002641.

Lumen N, Monstrey S, Goessaert A-S, Oosterlinck W, Hoebeke P. Urethroplasty for Strictures After Phallic Reconstruction: A Single-Institution Experience. Eur Urol. 2011;60:150–8.

Reddy SA, Holdren C, Srikanth P, Crane CN, Santucci RA. Urethroplasty Methods for Stricture Repair After Gender Affirming Phalloplasty: High Failure Rates in a Hostile Surgical Field. Urology. 2023;179:196–201.

De Rooij FPW, Falcone M, Waterschoot M, Pizzuto G, Bouman M-B, Gontero P, et al. Surgical Outcomes After Treatment of Urethral Complications Following Metoidioplasty in Transgender Men. J Sex Med. 2022;19:377–84.

Lumen N, Waterschoot M, Verla W, Hoebeke P. Surgical repair of urethral complications after metoidioplasty for genital gender affirming surgery. Int J Impot Res. 2020;33:771–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-020-0328-3.

Wilson SC, Stranix JT, Khurana K, Morrison SD, Levine JP, Zhao LC. Fasciocutaneous flap reinforcement of ventral onlay buccal mucosa grafts enables neophallus revision urethroplasty. Ther Adv Urol. 2016;8:331–7.

Lumen N, Campos-Juanatey F, Dimitropoulos K, Greenwell T, Martins F, Osman N. EAU Guidelines on Urethral Strictures. 2024. http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilations-of-all-guidelines/.

Anderson KT, Vanni AJ, Erickson BA, Myers JB, Voelzke B, Breyer BN, et al. Defining Success after Anterior Urethroplasty: An Argument for a Universal Definition and Surveillance Protocol. J Urol. 2022;208:135–43.

Mantica G, Verla W, Cocci A, Frankiewicz M, Adamowicz J, Campos-Juanatey F, et al. Reaching Consensus for Comprehensive Outcome Measurement After Urethral Stricture Surgery: Development of Study Protocol for Stricture-Fecta Criteria. Res Rep Urol. 2022;14:423–6.

Erickson BA, Ghareeb GM. Definition of Successful Treatment and Optimal Follow-up after Urethral Reconstruction for Urethral Stricture Disease. Urol Clin North Am. 2017;44:1–9.

Neuville P, Carnicelli D, Marcelli F, Karsenty G, Madec F-X, Morel-Journel N. Evaluation and follow-up for urethral strictures treatment. Fr J Urol. 2024;34:102713.

Wessells H, Morey A, Souter L, Rahimi L, Vanni A. Urethral Stricture Disease Guideline Amendment (2023). J Urol. 2023;210:64–71.

Madec F-X, Karsenty G, Yiou R, Robert G, Huyghe E, Boillot B, et al. Which management for anterior urethral stricture in male? 2021 guidelines from the Uro-genital Reconstruction Urologist Group (GURU) under the aegis of CAMS-AFU (Committee of Andrology and Sexual Medicine of the French Association of Urology). Prog En Urol J Assoc Francaise Urol Soc Francaise Urol. 2021;31:1055–71.

Berli JU, Monstrey S, Safa B, Chen M. Neourethra Creation in Gender Phalloplasty: Differences in Techniques and Staging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:801e–811e.

Pansritum K, Yingthaweesittikul S, Attainsee A. Urethral reconstruction with peritoneal graft in phalloplasty for male transgender. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75:2387–440.

Cohen O, Stranix JT, Zhao L, Levine J, Bluebond-Langner R. Use of a Split Pedicled Gracilis Muscle Flap in Robotically Assisted Vaginectomy and Urethral Lengthening for Phalloplasty: A Novel Technique for Female-to-Male Genital Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:1512–5.

Al-Tamimi M, Pigot GL, van der SWB, van de GTC, Mullender MG, Groenman F, et al. Colpectomy Significantly Reduces the Risk of Urethral Fistula Formation after Urethral Lengthening in Transgender Men Undergoing Genital Gender Affirming Surgery. J Urol. 2018;200:1315–22.

Abdel-Rassoul M, El Shorbagy G, Kotb S, Alagha A, Zamel S, Rammah AM. Management of urethral complications after total phallic reconstruction: a single center experience. Cent Eur J Urol. 2024;77:310–9.

Jung H, Chen ML, Wassersug R, Mukherjee S, Kumar S, Mankowski P, et al. Urethroplasty Outcomes for Pars Fixa Urethral Strictures Following Gender-affirming Phalloplasty and Metoidioplasty: A Retrospective Study. Urology. 2023;182:89–94.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Hospices Civils de Lyon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization Data curation Formal analysis Funding acquisition Investigation Methodology Project administration Software Resources Supervision Validation Visualization Writing – original draft Writing – review & editing. PN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft; FXM: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization; MWV: Project administration, Supervision, Validation; JA: Project administration, Software; ŁB: Software, Resources; FCJ: Methodology, Project administration; FC: Data curation, Formal analysis; AC: Supervision; MF: Resources, JK: Project administration, GM: Writing – review & editing; MO: Conceptualization, EJR: Writing – review & editing, CMR: Writing – review & editing; WV: Writing – original draft; MW: Investigation; DC: Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization; NMJ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neuville, P., Madec, FX., Vetterlein, M.W. et al. Systematic review of the outcomes of urethroplasty following urethral lengthening in transgender men. Int J Impot Res (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-025-01132-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-025-01132-4