Abstract

Kagome metal TbMn6Sn6 was recently discovered to be a ferrimagnetic topological Dirac material by scanning tunneling microscopy/spectroscopy measurements. Here, we report the observation of large anomalous Nernst effect and anomalous thermal Hall effect in this compound. The anomalous transverse transport is consistent with the Berry curvature contribution from the massive Dirac gaps in the 3D momentum space as demonstrated by our first-principles calculations. Furthermore, the transverse thermoelectric transport exhibits asymmetry with respect to the applied magnetic field, i.e., an exchange-bias behavior. Together, these features place TbMn6Sn6 as a promising system for the outstanding thermoelectric performance based on anomalous Nernst effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of topological materials with non-trivial electronic band topology has led to the prediction and realization of various topological insulators, metals, and semimetals1,2,3. In particular, magnetic topological materials are currently under intense research efforts owing to a variety of intriguing phenomena stemming from the integration of magnetism and topological electronic properties, such as quantized anomalous Hall effect4, axion insulator5, topological Fermi arc, and chiral anomaly6, etc. Notable examples of single-phase, intrinsic magnetic topological materials include the antiferromagnetic Weyl semimetal in Mn3(Sn/Ge)7,8 and GdPtBi9,10, the antiferromagnetic topological insulator in MnBi2Te411,12, the ferromagnetic Weyl semimetal in Co3Sn2S213, and Co2Mn(Ga, Al)14,15, the ferromagnetic Dirac metal in Fe3Sn216,17,18.

Most of the previous studies of magnetic topological materials have been focused on the non-trivial band topology, the corresponding surface states, and the intrinsic anomalous Hall effect (AHE)19. Charge carriers acquire an ‘anomalous velocity’ arising from the Berry curvature of electronic bands, which leads to the anomalous transverse conductivities. Recently, there has been surging interest in the anomalous Nernst effect (ANE) in magnetic topological materials due to the following two merits. From the scientific viewpoint, the anomalous Nernst coefficient is more sensitive than the AHE to the Berry curvature near the Fermi level, serving as a complementary tool in characterizing the Berry phase distribution in the reciprocal space20,21. From the viewpoint of technological applications, the ANE-based design allows for building malleable thermoelectric modules by patterning the thermopile onto flexible substrates22,23,24,25,26,27,28. This is illustrated by the schematic shown in Fig. 1a, where magnetic topological materials with alternating magnetization are patterned next to each other and electrically connected in series, which can lead to a large thermoelectric voltage output. However, as the thermopile density continues to increase, the inherent magnetic stray field generated by neighboring modules may perturb the magnetization of individual modules, reducing the total output voltage22. One way to circumvent this issue is to pin the magnetization of modules, which can be achieved via the exchange-bias mechanism. Exchange-bias refers to a phenomenon in which the field-dependent hysteresis loops of a measured quantity shift along the applied magnetic field-axis, which has been the most commonly observed in the magnetization data of heterostructures consisting of both ferromagnet and antiferromagnet29. More recently, exchange-bias phenomenon has also been observed in crystalline single-phase compounds30,31. Therefore, identifying materials hosting both large ANE as well as an exchange-bias feature is an important next step in realizing such designs.

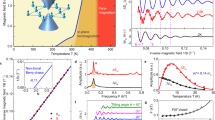

a An illustration of thermoelectric devices utilizing anomalous Nernst effect. The color is an indication of magnetization direction for each module (along the z or −z direction), the gray strips represent electric connections, and the temperature gradient is along the y direction. b Schematic crystal structure of TbMn6Sn6 with manganese atoms shown in red, terbium in black and tin in blue. c Magnetic susceptibility data for TbMn6Sn6. Blue and red curves are the zero-field cooled and field cooled \({\chi }_{c}\) data and black curve is the field cooled \({\chi }_{a}\). The applied magnetic field is 0.1 T. d Temperature dependence of the longitudinal thermal conductivity \({\kappa }_{{xx}}\) and resistivity \({\rho }_{{xx}}\).

Here we report comprehensive electrical, thermal, and thermoelectric measurements on a ferrimagnetic Kagome metal TbMn6Sn6. In addition to AHE, we show that TbMn6Sn6 exhibits both large ANE (2.2 μV/K at 300 K) and anomalous thermal Hall effect (ATHE, 0.12 W/mK at 300 K). Our first-principles calculations demonstrate that the large Berry curvature of the massive Dirac gaps in the 3D momentum space leads to the intrinsic anomalous transverse conductivities. Furthermore, we observe exchange-bias behavior in the field dependence of all these traverse transport quantities. This study highlights the potential of utilizing this magnetic topological material as a thermoelectric module.

Results

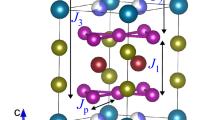

TbMn6Sn6 belongs to a member of the RMn6Sn6 (R = rare earth, Y, Sc, Lu) series. The manganese atoms in these compounds form a double-layer Kagome lattice structure, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. Spins within each Kagome plane are ferromagnetically aligned while the spin alignment between Kagome planes depends on R elements32,33. The unique Kagome lattice can give rise to flat bands and Dirac points in the band structure34,35. The former provides an ideal platform for studying strongly correlated phenomena, while the latter is an interesting topological object by its own right. In particular, TbMn6Sn6 stands out as a ferrimagnet with out-of-plane magnetization where Tb moment aligns antiferromagnetically with Mn moment36. As a result, the electronic band structure of TbMn6Sn6 exhibits spin-polarized Dirac dispersion with a Chern gap, as reported in refs. 37,38, recently. The massive Dirac bands near the Fermi energy can give rise to anomalous electric and heat transport phenomena.

We first present the magnetic susceptibility measurements of TbMn6Sn6 in Fig. 1c. The red solid curve and blue dashed curve shown here represent the field-cooled (FC) and zero-field-cooled (ZFC) susceptibility respectively measured along the crystalline c-axis with 0.1 T magnetic field, and the black solid curve represents the susceptibility measured along the a-axis. As seen in the inset of Fig. 1c, there is a substantial decrease of \({\chi }_{c}\) above Tsr ≈ 309 K, which is accompanied with a sharp increase of \({\chi }_{a}\). This is due to a spin re-orientation process as supported by neutron diffraction measurements39. Below Tsr, both Tb and Mn magnetic moments, which are antiferromagnetically coupled to each other, switch from an in-plane configuration to an out-of-plane structure. Note that TbMn6Sn6 undergoes paramagnetic-to-ferrimagnetic phase transition at Tc = 423 K36. Interestingly, the FC and ZFC \({\chi }_{c}(T)\) curves bifurcate noticeably below 200 K, which is presumably associated with the presence of slow magnetic fluctuation, as revealed by μSR recently, that leads to the formation of magnetic domains during the ZFC process39. As will be discussed later, such domain formation also gives rise to distinct hysteresis features in different temperature regions.

Figure 1d plots the temperature dependence of longitudinal transport coefficients \(\left({\kappa }_{{xx}},{\rho }_{{xx}}\right)\) of TbMn6Sn6. The resistivity, represented by the blue curve, decreases monotonically with temperature, and the residual resistance ratio is found to be 102.9, indicating good crystal quality. The thermal conductivity, shown in red, exhibits a typical broad peak around 30 K, resulting from the competition between boundary/defect scattering (at low temperature) and the Umklapp scattering (at high temperature). The Seebeck coefficient \({S}_{{xx}}\) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 in the Supplementary Information, linearly decreases with temperature above 160 K followed by a nearly constant feature in the temperature range between 80 to 160 K. Phonon or magnon drag process may account for the slow decrease of \({S}_{{xx}}\) at low temperature. A similar behavior in Seebeck coefficient has been observed recently in Weyl semimetals Co2MnGa and Co3Sn2S223,40.

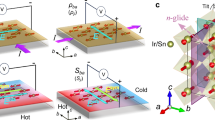

Next, we present the field dependence of transverse transport coefficients of TbMn6Sn6. The AHE with an intrinsic anomalous Hall conductivity (\({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{int}}=0.14{e}^{2}/h\) per kagome bilayer) has been observed in TbMn6Sn6, which was attributed to the Berry curvature in Dirac bands37. For completeness, in Fig. 2 we have included our own field-dependent anomalous Hall conductivity (\({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\)) data, together with the anomalous Nernst signal (\({S}_{{xy}}^{A}/T\)) and anomalous thermal Hall conductivity (\({\kappa }_{{xy}}^{A}\)). The sign conversion of transverse transport measurements and the subtraction of the normal transverse components of these quantities have been described in detail in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 2, and Supplementary Figs. 3–6). And all these three quantities measured at various temperatures are intentionally shifted along the Y-axis by a certain value for clarity. Note that the thermoelectric and thermal transport measurements were done in an adiabatic manner (Supplementary Fig. 7). There are several interesting features worth pointing out. First, the curves of \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\), \({\kappa }_{{xy}}^{A}\), and \({S}_{{xy}}^{A}\) measured at the same temperature have nearly identical features, implying that all these anomalous transverse transport properties stem from the same origin, i.e., the Berry curvature of the electronic bands. This is supported by the theoretical calculations as will be discussed latter. Second, the hysteresis loops measured above 200 K exhibit very small remanence, in contrast to the hysteresis loops measured at lower temperatures. The low remanence in hysteresis loops above 200 K is presumably due to the strong magnetic fluctuations, which is recently revealed by μSR measurements39. In contrast, magnetic fluctuations slow down at lower temperatures. Third, interestingly, an exchange-bias feature (i.e., the center of the hysteresis loop is shifted away from the origin along the field-axis) is observed in the hysteresis loops of \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\), \({\kappa }_{{xy}}^{A}\), and \({S}_{{xy}}^{A}\) measured below 200 K. This exchange-bias behavior will be discussed in further details later. The exchange-biased ANE observed in TbMn6Sn6 renders it as a promising material for realizing the proposed thermoelectric devices utilizing ANE.

Magnetic field dependence of anomalous Hall conductivity \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\) (a), anomalous Nernst coefficients scaled by temperature \({S}_{{xy}}^{A}/T\) (b), and anomalous thermal Hall conductivity \({\kappa }_{{xy}}^{A}\) (c) measured at selected temperatures. d Temperature dependence of anomalous Hall conductivity \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\) and the thermal Hall conductivity normalized to temperature \({\kappa }_{{xy}}^{A}/T\). Error bars were obtained through the fitting methods described in the Supplementary Information. e Temperature dependence of anomalous Nernst coefficient (\({S}_{{xy}}^{A}\)).

In Fig. 2d, e, we summarize the temperature dependence of the anomalous transport coefficients. The blue symbols in Fig. 2d represent \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}(T)\) which increases monotonically with the decrease of temperature. The increase of \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\) at low temperatures mainly arises from the enhanced skew scattering (\({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{sk}}\propto {\sigma }_{{xx}}\)) contributions. It is unlikely that the side jump (\({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{sj}}\)) mechanism has a major contribution since the electric conductivity (\({\sigma }_{{xx}}\)) of TbMn6Sn6 is high and therefore far away from the ‘Localized-hopping conduction region’19. To extract the intrinsic anomalous Hall conductivity \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{int}}\), we assume the total AHE signal is composed of the intrinsic contribution and the extrinsic skew scattering contribution, i.e., \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}={\rho }_{{yx}}^{{sk}}+{\rho }_{{yx}}^{{int}}=A{\rho }_{{xx}}+B{\rho }_{{xx}}^{2}\). By plotting \({\rho }_{{xy}}^{A}\) as a function of \({\rho }_{{xx}}\) (Supplementary Fig. 8) and fitting it to the equation above, the intrinsic anomalous Hall conductivity is extracted to be \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{int}}=131\pm 20\,{\left(\Omega {{{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}}}\right)}^{-1}\), which is in good agreement with the recent study37. The extracted \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{int}}\) is smaller than the measured \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\), suggesting the extrinsic contribution to \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\). The red symbols in Fig. 2d represent the measured anomalous thermal Hall conductivity normalized to temperature \(({\kappa }_{{xy}}^{A}/T)\), which shows a similar behavior to that of \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}(T)\). Note that the scales of the left and right axes of Fig. 2d are related by the Lorenz number \(\left({L}_{0}=2.44\times {10}^{-8}\,{{{{{{\rm{V}}}}}}}^{2}{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}^{-2}\right)\). Alternatively, a plot of L/L0 (L = \(\frac{{\kappa }_{{xy}}^{A}}{{\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}T}\)) as a function of temperature is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. One can clearly see that the ‘anomalous’ Wiedemann–Franz law \(({\kappa }_{{xy}}^{A}={L}_{0}T{\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A})\)41 is obeyed for the anomalous transverse transport in TbMn6Sn6 within the measured temperature range. Figure 2e presents the temperature dependence of the anomalous Nernst coefficient \(({S}_{{xy}}^{A})\). While \({S}_{{xy}}^{A}\) monotonically decreases with temperature, it appears that \({S}_{{xy}}^{A}\) decreases in a faster manner in the higher temperature region compared to that at lower temperatures. Note that no anomalous Nernst signal is convincingly observed below 50 K.

To further our understanding of the origin of the anomalous Hall and thermoelectric conductivity in TbMn6Sn6, we performed density-functional theory (DFT) calculations within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) framework42,43. Based on the calculated electronic structure, we projected the Bloch wave functions into Wannier functions to construct an effective Hamiltonian and evaluate the Berry curvature distributions in the reciprocal space. Figure 3a shows the calculated band structure and corresponding projected Berry curvature \((-{\Omega }_{{xy}})\). In all calculations, spin-orbit coupling (SOC) has been taken into account. The SOC opens a bandgap at Dirac points (K-points) near the Fermi energy EF [see an expanded view in Supplementary Fig. 10], giving rise to large Berry curvature with opposite signs for the upper and lower bands. In addition to the massive Dirac points, there are extra Berry curvature contributions for the band anti-crossing along kz. Figure 3b presents the Berry curvature distribution in 3D Brillouin zone at EF. Our results show that TbMn6Sn6 is a multi-band system beyond the simple kagome model. The massive Dirac points together with other bands contribute to the AHE.

a Left panel: electronic band structure and the projected Berry phase (\(-{\Omega }_{{xy}}\)) for bands near the Fermi energy. The experimental Fermi energy (EF, dashed line) is 90 meV lower than the charge-neutral point (zero). b Visualization of Berry curvature distribution in 3D Brillouin zone at EF. c Calculated intrinsic anomalous Hall conductivity (\({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\)) as a function of the Fermi energy at zero temperature. d Temperature dependence of the measured (blue), the calculated (yellow), and the scaled calculated (orange) transverse thermoelectric conductivity normalized by temperature \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{A}/T\).

Using the Kubo-formula approach20, we calculated the intrinsic value of \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{int}}\) and the intrinsic transverse thermoelectric conductivity \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{{int}}\). Figure 3c shows the calculated \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{int}}\) as a function of energy, where the Fermi energy EF is shifted down by 90 meV from the charge-neutral point to optimally fit AHE and ANE. At the Fermi level, the calculated \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{{{{{{\rm{int}}}}}}}}=120\,{\left(\Omega {{{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}}}\right)}^{-1}\), which is in close agreement with the value extracted from the experimental results [Supplementary Fig. 8]. Figure 3d plots the comparison between the calculated anomalous thermoelectric conductivity normalized to temperature and the experimental results (\({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{A}/T\), blue dots), the latter of which are obtained using \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{A}={\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}{S}_{{xx}}+{\sigma }_{{xx}}{S}_{{xy}}^{A}\)44. The yellow curve shows the temperature dependence of \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{{int}}/T\) calculated using Kubo formula, \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{{int}}\left(T\right)=-\frac{e}{\hslash }\int d\zeta \frac{\partial f\left(\zeta -\mu \right)}{\partial \zeta }\,\frac{\zeta -\mu }{T}{\int }_{{BZ}}\frac{d\vec{k}}{{\left(2\pi \right)}^{3}}{\sum}_{{\epsilon }_{n} \, < \, \zeta }{\Omega }_{{xy}}^{z}(\vec{k})\), wherein \(f\left(\zeta -\mu \right)=({e}^{\frac{\zeta -\mu }{{k}_{B}T}}+1)\) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution function and \(\mu\) is the chemical potential. We can see that while the calculated \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{{int}}/T\) and the experimental values agree reasonably well at high temperature, they deviate at low temperature with the calculated values smaller than the experimental results. Such difference is mainly attributed to the enhanced skew scattering contribution to \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{A}\) (via \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\)) as the system approaches a ‘clean limit’ (increase of \({\sigma }_{{xx}}\)). Similar features have been observed recently in other topological materials14,22,23,40. To take into account the effect due to the enhanced skew scattering, we recall the Mott relation (\(\frac{{\alpha }_{{xy}}^{A}}{T}{|}_{T\to 0}=-\frac{{\pi }^{2}{k}_{B}^{2}}{3\left|e\right|}\frac{d{\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}}{d\zeta }{|}_{\mu }\)), which states that the magnitude of \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{A}/T\) is proportional to the derivative of \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\) relative to energy at the Fermi level. As mentioned previously, in addition to \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{int}}\), \({\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}\) also includes the skew scattering contribution which can lead to ANE via the Mott relation. Thus, it is reasonable for us to scale the calculated \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{{int}}/T\) value by a temperature-dependent factor \(\beta \left(T\right)={\sigma }_{{xy}}^{A}/{\sigma }_{{xy}}^{{int}}\), which is shown by the orange curve in Fig. 3d. Although this is a coarse estimate of the skew scattering contribution, we can see that indeed the scaled, calculated \(\beta {\alpha }_{{xy}}^{{int}}/T\) and the experiment values tend to merge at low temperatures. This feature, together with the closeness between the calculated \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{{int}}/T\) and the experimental \({\alpha }_{{xy}}^{A}/T\) at high temperature, indicates the effects of band structure topology on the transverse thermoelectric transport properties in TbMn6Sn6.

We now discuss the asymmetric field dependence feature observed in the transverse transport measurements shown in Fig. 2a–c. Such a feature is also observed in isothermal magnetization measurements conducted under the same experimental procedure, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, which indicates that magnetism, electronic, and thermal transport properties intimately correlate with each. To further affirm that the asymmetric field dependence feature is intrinsic and associated with the exchange-bias, we have studied both temperature dependence and cooling field dependence of exchange-biasing field. Figure 4a and Supplementary Fig. 12 show the M(H) data measured at various temperatures. For clarity, each magnetization data M(H) is shifted along the magnetization axis by a certain value. Prior to each M(H) measurement, the sample was warmed up to 340 K and then cooled down to the measurement temperature with an applied field of 0.5 T. It is clearly seen that the shift of the center of hysteresis loops away from the origin of the field-axis. i.e., the exchange-biasing field (\({\mu }_{0}{H}_{{EB}}\)), emerges below 200 K and gradually increases as the temperature decreases, as shown by the blue symbols presented in Fig. 4c. Figure 4b shows the M(H) data measured at T = 100 K after the sample was cooled down from 340 K with different cooling fields (HFC). HEB increases with HFC and nearly saturates above 0.6 T, as illustrated in Fig. 4d. And as shown in Fig. 4e, HEB switches the sign when the sign of HFC reverses. In addition, we also examined the training effect of the exchange-bias behavior in TbMn6Sn6. The sample was cooled down from 340 to 100 K with different cooling fields. After each field cooling, complete M(H) loops were then acquired continuously for three times without subsequent warming up and cooling down processes. The obtained M(H) data are shown in Fig. 4f. Clearly, the sample exhibits prominent training effect with the exchange-biasing field HEB value deceasing dramatically upon repeating the measurements after the first loop cycle, a feature similar to as observed in heterostructures composed of spin glass and ferromagnet bilayers45. Note that the transverse transport data shown in Fig. 2a–c and the M(H) data shown in Supplementary Fig. 11 were taken after the sample was initially cooled down to 100 K with 1.5 T magnetic field but without the subsequent warming up and cooling down processes for the measurements at each temperature. Thus, the resultant \({\mu }_{0}{H}_{{EB}}\) is smaller compared to the values shown in Fig. 4a due to the training effect. All these phenomena presented in Fig. 4b are characteristic of the exchange-bias behavior, affirming our finding of exchange-bias feature in single-crystalline TbMn6Sn6.

a Magnetization hysteresis loops measured at various temperatures after the sample was cooled down from 340 K to the measurement temperature with 0.5 T magnetic field prior to each measurement. b Magnetization hysteresis loops measured at 100 K after the sample was cooled down from 340 to 100 K with different magnetic field prior to measuring each loop. c Temperature dependence of the exchange-biasing field \({\mu }_{0}{H}_{{EB}}\) extracted from (a). Orange dots represent the saturated magnetizations at respective temperatures. d The cooling field (HFC) dependence of the exchange-biasing field extracted from (b). e Magnetization hysteresis loops measured at T = 100 K with 0.5 and −0.5 T cooling field. f Magnetization hysteresis loops measured at T = 100 K upon repeating the measurements after the sample was cooled down with various cooling fields.

Discussion

The observation of exchange-bias feature in both magnetization and transverse transport measurements in TbMn6Sn6 is interesting and perplexing. It is worth noting that the dynamic depolarization rate of the μSR signal in TbMn6Sn6 increases appreciably below 200 K as well, indicating the slowing down of magnetic fluctuations39. This implies its close correlation with the observed exchange-bias feature. We have performed DFT calculations on the exchange interactions in the Mn Kagome lattice and found that ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange couplings between two nearest-neighboring Mn kagome planes compete, compared to the dominant intralayer ferromagnetic coupling (see Supplementary Fig. 13). In addition, it is known that the interlayer couplings between further neighboring Mn Kagome planes in RMn6Sn6, which are sensitive to the R element, also compete to determine their overall spin structures33. We speculate that in TbMn6Sn6, as the magnetic fluctuations slows down, the competition of interlayer couplings between Mn spins, together with the antiferromagnetic Tb-Mn interlayer coupling, may lead to the formation of the cluster spin-glass state with antiferromagnetic domains embedded in and coexisting with the bulk ferromagnetic phase of Mn spins. As a result, the interface between antiferromagnetic domains and ferromagnetic phase of Mn spins gives rise to exchange-bias features with asymmetry in the AHE and ANE hysteresis. One may engineer the exchange-bias by partial substitution on the rare earth site without affecting the Mn site to tune the interlayer couplings of Mn spins. The existence of a cluster spin-glass phase in TbMn6Sn6 is evidenced by the ac susceptibility measurements shown in Supplementary Fig. 14. The exchange-bias feature between spin-glass and ferromagnet phases was previously discovered, but in the heterostructure form45,46.

Finally, we would like to comment on the distinctions and similarities between TbMn6Sn6 and other magnetic topological materials that show ANE14,22,23,40,47,48,49. First, it is worth emphasizing that TbMn6Sn6 exhibits large Berry curvature mainly due to massive Dirac bands near K points. The K-point Dirac gap originates from gapping a vertical nodal line along the K-H direction [see Fig. 3a]. There is another hot spot of Berry curvature around kz = 0.3, which reveals rich topology in the band structure. In contrast, many other magnetic topological materials show Berry curvature from Weyl points [e.g., Co3Sn2S2 and Mn3(Sn,Ge)]22,23 or gapped giant nodal rings [e.g., Co2Mn(Ga,Al), Fe3(Ga,Al)]14,15,48. The Wiedemann–Franz law is well preserved up to the room temperature for TbMn6Sn6, different from magnetic Weyl semimetals Co3Sn2S2 and Mn3Ge where the Lorenz ratio deviates above 100 K41,50. This is because that massive Dirac bands exhibit smoother Berry curvature variation with respect to the Fermi energy, compared to Weyl points. Second, in Fig. 5 we show a scatter plot of \({S}_{{xy}}\) versus M for different topological magnetic materials. The pink shaded region represents the lower and upper bounds of \({S}_{{xy}}\) and M for conventional ferromagnets in which \({S}_{{xy}}\) tends to be proportional to M22. Note that both Mn3Sn and Mn3Ge are antiferromagnets with very weak canted ferromagnetic moment, and the ANE signal is determined by the Berry curvature of electron bands and thus \({S}_{{xy}}\) does not scale linearly with M22,47. Interestingly, similar to other topological ferromagnets listed, the \({S}_{{xy}}\)(M) of TbMn6Sn6 also falls outside the pink shaded region, implying the contribution of Berry curvature to its ANE signal as supported by the theoretical calculation presented in Fig. 3c. In addition, while \({S}_{{xy}}\) of TbMn6Sn6 is comparable to or slightly smaller than those of Fe3Sn249, Fe3Al48, Fe3Ga48, and Co2MnGa14,40, it has much lower magnetization compared to others. This is an important aspect, particularly considering that TbMn6Sn6 exhibits the unique exchange-bias feature described above. As shown in Fig. 4c, M of TbMn6Sn6 is even much smaller than exchange-biasing field \({\mu }_{0}{H}_{{EB}}\). Thus, as discussed previously in the introduction, one can utilize the large exchange-biasing field to circumvent the stray field interference arising from neighboring thermoelectric modules that are connected in series. This allows for much larger integration density of thermopile and improves the device performance with a significantly enhanced Nernst signal.

In summary, we have reported the prominent AHE, ANE, and ATHE behavior of TbMn6Sn6 which is ferrimagnetic Kagome metal hosting a Chern gap near the Fermi level. We show that these anomalous transverse conductivities are associated with large Berry phase in the reciprocal space. Furthermore, we find that TbMn6Sn6 exhibits an exchange-bias feature in both magnetization and transverse conductivity measurements. This, combined with the large ANE, places TbMn6Sn6 as a promising system for transverse thermoelectric devices based on the Nernst effect.

Methods

TbMn6Sn6 single crystals were grown using the flux method37. It crystalizes in the hexagonal structure with a space group P6/mmm (No. 191) with lattice constants a = b = 5.522 Å, c = 9.004 Å and crystalline angles α = β = 90°, γ = 120°. Magnetic susceptibility measurements of TbMn6Sn6 were carried out using a Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (SQUID) magnetometer. Resistivity and Hall effect measurements were conducted using a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS). Thermal and thermoelectric transport measurements were performed using a homemade sample puck designed to be compatible with the PPMS cryostat. Type-E thermocouples (Chromel-Constantan) were used for temperature measurement. The thermoelectric voltage was measured using K2182A Nanovoltmeters (Keithley). The ‘cold-end’ of the sample is attached to a piece of oxygen-free high conductivity copper using silver epoxy. A resistive heater (~1 kΩ) was attached to the other end of the sample and the heat current JQ was applied in the ab plane. The magnetic field was applied along the out-of-plane direction, i.e., c-axis. Both the experimental set-up and data processing of the measured transverse coefficients are described in detail in the Supplementary Information.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that supports the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The theory calculations are performed via standard density-functional theory package, Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP, https://www.vasp.at/). The codes that support the plots and data analysis within this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Yan, B. & Felser, C. Topological materials: Weyl semimetals. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 8, 337–354 (2017).

Armitage, N. P., Mele, E. J. & Vishwanath, A. Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001 (2018).

Yu, R. et al. Quantized anomalous Hall effect in magnetic topological insulators. Science 329, 61–64 (2010).

Mong, R. S. K., Essin, A. M. & Moore, J. E. Antiferromagnetic topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 81, 245209 (2010).

Wan, X., Turner, A. M., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Topological semimetal and Fermi-arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205101 (2011).

Nakatsuji, S., Kiyohara, N. & Higo, T. Large anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet at room temperature. Nature 527, 212–215 (2015).

Yang, H. et al. Topological Weyl semimetals in the chiral antiferromagnetic materials Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn. N. J. Phys. 19, 015008 (2017).

Hirschberger, M. et al. The chiral anomaly and thermopower of Weyl fermions in the half-Heusler GdPtBi. Nat. Mater. 15, 1161–1165 (2016).

Suzuki, T. et al. Large anomalous Hall effect in a half-Heusler antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 12, 1119–1123 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Intrinsic magnetic topological insulators in van der Waals layered MnBi2Te4-family materials. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw5685 (2019).

Otrokov, M. M. et al. Prediction and observation of an antiferromagnetic topological insulator. Nature 576, 416–422 (2019).

Liu, E. et al. Giant anomalous Hall effect in a ferromagnetic kagome-lattice semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1125–1131 (2018).

Sakai, A. et al. Giant anomalous Nernst effect and quantum-critical scaling in a ferromagnetic semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1119–1124 (2018).

Li, P. et al. Giant room temperature anomalous Hall effect and tunable topology in a ferromagnetic topological semimetal Co2MnAl. Nat. Commun. 11, 3476 (2020).

Ye, L. et al. Massive Dirac fermions in a ferromagnetic kagome metal. Nature 555, 638–642 (2018).

Yin, J.-X. et al. Giant and anisotropic many-body spin–orbit tunability in a strongly correlated kagome magnet. Nature 562, 91–95 (2018).

Kida, T. et al. The giant anomalous Hall effect in the ferromagnet Fe3Sn2—a frustrated kagome metal. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 23, 112205 (2011).

Nagaosa, N., Sinova, J., Onoda, S., MacDonald, A. H. & Ong, N. P. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1539–1592 (2010).

Xiao, D., Yao, Y., Fang, Z. & Niu, Q. Berry-phase effect in anomalous thermoelectric transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 026603 (2006).

Miyasato, T. et al. Crossover behavior of the anomalous Hall effect and anomalous Nernst effect in itinerant ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 086602 (2007).

Ikhlas, M. et al. Large anomalous Nernst effect at room temperature in a chiral antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 13, 1085–1090 (2017).

Guin, S. N. et al. Zero-field Nernst effect in a ferromagnetic kagome-lattice Weyl-semimetal Co3Sn2S2. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806622 (2019).

Sakuraba, Y. et al. Anomalous Nernst effect in L10-FePt/MnGa thermopiles for new thermoelectric applications. Appl. Phys. Express 6, 033003 (2013).

Sakuraba, Y. Potential of thermoelectric power generation using anomalous Nernst effect in magnetic materials. Scr. Materialia 111, 29–32 (2016).

Melo, A. S. et al. Anomalous Nernst effect in stressed magnetostrictive film grown onto flexible substrate. Sci. Rep. 9, 15338 (2019).

Zhou, W. & Sakuraba, Y. Heat flux sensing by anomalous Nernst effect in Fe–Al thin films on a flexible substrate. Appl. Phys. Express 13, 043001 (2020).

Wang, J., Miura, A., Modak, R., Takahashi, Y. K. & Uchida, K.-I. Magneto-optical design of anomalous Nernst thermopile. Sci. Rep. 11, 11228 (2021).

Nogués, J. & Schuller, I. K. Exchange bias. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 192, 203–232 (1999).

Maniv, E. et al. Exchange bias due to coupling between coexisting antiferromagnetic and spin-glass orders. Nat. Phys. 17, 525–530 (2021).

Lachman, E. et al. Exchange biased anomalous Hall effect driven by frustration in a magnetic kagome lattice. Nat. Commun. 11, 560 (2020).

Venturini, G., Fruchart, D. & Malaman, B. Incommensurate magnetic structures of RMn6Sn6 (R = Sc, Y, Lu) compounds from neutron diffraction study. J. Alloy. Compd. 236, 102–110 (1996).

Malaman, B. et al. Magnetic properties of RMn6Sn6 (R = Gd–Er) compounds from neutron diffraction and Mössbauer measurements. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 202, 519–534 (1999).

Guo, H. M. & Franz, M. Topological insulator on the kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. B 80, 113102 (2009).

Kang, M. et al. Dirac fermions and flat bands in the ideal kagome metal FeSn. Nat. Mater. 19, 163–169 (2020).

El Idrissi, B. C., Venturini, G., Malaman, B. & Fruchart, D. Magnetic structures of TbMn6Sn6 and HoMn6Sn6 compounds from neutron diffraction study. J. Less Common Met. 175, 143–154 (1991).

Yin, J.-X. et al. Quantum-limit Chern topological magnetism in TbMn6Sn6. Nature 583, 533–536 (2020).

Ma, W. et al. Rare Earth engineering in RMn6Sn6 (R = Gd-Tm, Lu) topological kagome magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 246602 (2021).

Mielke III, C. et al. Intriguing magnetism of the topological kagome magnet TbMn6Sn6. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.05763 (2021).

Guin, S. N. et al. Anomalous Nernst effect beyond the magnetization scaling relation in the ferromagnetic Heusler compound Co2MnGa. NPG Asia Mater. 11, 16 (2019).

Xu, L. et al. Finite-temperature violation of the anomalous transverse Wiedemann-Franz law. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz3522 (2020).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Liang, T. et al. Anomalous Nernst effect in the Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 136601 (2017).

Chi, X. et al. Exchange bias training relaxation in spin glass/ferromagnet bilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 172401 (2016).

Ali, M. et al. Exchange bias using a spin glass. Nat. Mater. 6, 70–75 (2007).

Wuttke, C. et al. Berry curvature unravelled by the anomalous Nernst effect in Mn3Ge. Phys. Rev. B 100, 085111 (2019).

Sakai, A. et al. Iron-based binary ferromagnets for transverse thermoelectric conversion. Nature 581, 53–57 (2020).

Zhang, H., Xu, C. Q. & Ke, X. Topological Nernst effect, anomalous Nernst effect, and anomalous thermal Hall effect in the Dirac semimetal Fe3Sn2. Phys. Rev. B 103, L201101 (2021).

Ding, L. et al. Quantum oscillations, magnetic breakdown and thermal Hall effect in Co3Sn2S2. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 54, 454003 (2021).

Acknowledgements

H.Z., M.S., and X.K. acknowledge the financial support by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under DE-SC0019259. C.X. is partially supported by the Start-up funds at Michigan State University. B.Y. acknowledges the financial support by the European Research Council (ERC Consolidator Grant “NonlinearTopo”, No. 815869) and the ISF−Personal Research Grant (No. 2932/21).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.K. supervised the project. C.X. grew the samples, H.Z., C.X., and M.S. fabricated the devices and performed the measurements. H.Z. analyzed the data. J.K. performed theoretical calculations with support from B.Y. H.Z. and X.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jia-Xin Yin and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Koo, J., Xu, C. et al. Exchange-biased topological transverse thermoelectric effects in a Kagome ferrimagnet. Nat Commun 13, 1091 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28733-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28733-7

This article is cited by

-

Frustrated magnetism, electronic, and thermodynamic properties of titanium-based kagome materials

Journal of Materials Science (2026)

-

Three-dimensional nature of anomalous Hall conductivity in YMn6Sn6−xGax, x ≈ 0.55

npj Quantum Materials (2025)

-

Tunable magnetism in titanium-based kagome metals by rare-earth engineering and high pressure

Communications Materials (2024)

-

Anisotropic magnetism and band evolution induced by ferromagnetic phase transition in titanium-based kagome ferromagnet SmTi3Bi4

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2024)

-

Field-linear anomalous Hall effect and Berry curvature induced by spin chirality in the kagome antiferromagnet Mn3Sn

Nature Communications (2023)