Abstract

Emergent color centers with accessible spins hosted by van der Waals materials have attracted substantial interest in recent years due to their significant potential for implementing transformative quantum sensing technologies. Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) is naturally relevant in this context due to its remarkable ease of integration into devices consisting of low-dimensional materials. Taking advantage of boron vacancy spin defects in hBN, we report nanoscale quantum imaging of low-dimensional ferromagnetism sustained in Fe3GeTe2/hBN van der Waals heterostructures. Exploiting spin relaxometry methods, we have further observed spatially varying magnetic fluctuations in the exfoliated Fe3GeTe2 flake, whose magnitude reaches a peak value around the Curie temperature. Our results demonstrate the capability of spin defects in hBN of investigating local magnetic properties of layered materials in an accessible and precise way, which can be extended readily to a broad range of miniaturized van der Waals heterostructure systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optically active spin defects in wide band-gap semiconductors promise to enable a broad range of emerging applications in quantum information sciences and technologies1,2,3,4. To date, nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond1,2, as well as divacancy and silicon-vacancy centers in silicon carbide3,4,5, have been among the most prominent candidates, and have been successfully applied to quantum sensing, computing, and network research, enabling unprecedented field sensitivity, spatial resolution, and state-of-the-art spin-qubit operations2,6,7. Many of these advantages derive from the quantum-mechanical nature of these spin defects, which are endowed with excellent quantum coherence, single-spin addressability, and remarkable functionality over a broad temperature range1,3,4,5,8,9.

More recently, the flourishing catalog of van der Waals materials10 has provided a diverse new playground to enrich this field. There is ongoing and intense activity to explore emergent spin defects and color centers in atomic layers of van der Waals crystals, e. g. transition metal dichalcogenides MoS211,12, WSe212,13, and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN)12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. In comparison with their conventional counterparts imbedded in three-dimensional solid-state-media, spin defects hosted by two-dimensional (2D) materials exhibit improved versatility for implementing ultrasensitive quantum sensing of proximate objects and remarkable compatibility to device integration14,26. For instance, hexagonal boron nitride (hBN), one of the most intensively studied candidates, has been widely employed as an encapsulation layer and gate dielectric material in fabricating functional 2D devices29,30,31,32. Thus, nanoscale proximity between spin defects in a hBN thin sheet and a layered 2D material can be readily established in van der Waals heterostructures, offering a previously unexploited quantum sensing platform to explore the local physical quantities of interest in an accessible and precise way.

Despite these potential benefits and many pioneering studies, to date, experimental demonstration of quantum microscopy using spin defects in a real van der Waals heterostructure remains a formidable challenge. In this work, we report nanoscale quantum sensing and imaging of exfoliated 2D ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2 (FGT) flakes33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 by boron vacancy \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects in an adjacent hBN capping layer. Exploiting a wide-field magnetometry method42,43,44,45,46, we directly image the local magnetic texture of the FGT flake and its characteristic temperature and field dependent magnetization evolution behavior. Taking advantage of spin relaxometry techniques47,48,49,50,51, we have observed spatially varying spin fluctuations in the FGT flake, whose magnitude reaches a peak value around the Curie temperature, consistent with the expected ferromagnetic phase transition. We highlight that the presented quantum sensing platform built on spin defects in van der Waals crystals can be extended naturally to a large family of miniaturized 2D heterostructure systems10,52,53, bringing new opportunities for investigating the local spin, charge, and thermal properties of emergent quantum materials and devices.

Results

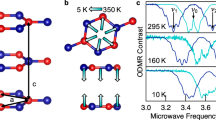

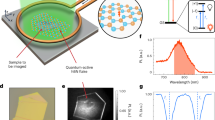

Before discussing the details of our experimental results, we first review our measurement platform and device structure, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. We exfoliated an FGT flake and mechanically transferred it onto a patterned Au microwave transmission line. Following this, we encapsulated the sample with an hBN layer. The device preparation process was performed in a glove box with argon environment to minimize environmental effects (see Methods for details). An optical microscope image shown in Fig. 1b provides an overview of a prepared device, where the thickness of the FGT and hBN flakes were characterized by atomic force microscopy (see Supplementary Information Note 1 for details). Boron vacancy \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects in the hBN flake were created by Helium ion implantation with an energy of 5 keV and a dose of 5 \(\times\) 1013 cm−2. Figure 1c illustrates the structure of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) in a hexagonal crystalline structure with alternating boron (red) and nitrogen (green) atoms, where three nitrogen atoms are adjacent to each boron atom vacancy \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\). The negatively charged \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defect has an S = 1 electron spin and serves as a three-level quantum system, as shown in Fig. 1d. In the present study, we used microwave currents flowing in the Au microwave transmission line to control the quantum spin state of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects, which can be optically accessed via spin-dependent photoluminescence (PL). The Au underlayer also enhances the PL and optical contrast of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects16, aiding the quantum microscopy measurements discussed below. The distance between the \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) defect centers and the top surface of the FGT sample is estimated to be ~50 nm based on Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter (SRIM) simulations. Exfoliated FGT flakes show spontaneous perpendicular magnetization due to reduced crystal symmetry of the layered structure33,35,36. We have prepared separate devices to systematically and reproducibly characterize the magneto-transport properties of exfoliated FGT flakes, whose Curie temperature is measured to be ~200 K, in qualitative agreement with previous studies (see Supplementary Information Note 2 for details)33,35,40.

a Schematic of a Fe3GeTe2(FGT)/hBN van der Waals heterostructure transferred onto an Au microwave stripline for wide-field magnetometry measurements. b Optical microscope image of a prepared FGT/hBN device. The FGT and hBN flakes are outlined with red and black dashed lines, respectively. The scale bar is 5 \({{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\)m. c Schematic of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects (blue arrows) formed in a hexagonal crystalline structure with alternating boron (red) and nitrogen (green) atoms. A negatively charged boron atom vacancy \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) is surrounded by three nitrogen atoms located in the nearest neighboring sites. d Energy level diagram of a \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defect and schematic illustration of optical excitation (green arrow), radiative recombination (red arrow), and nonradiative decay (black dotted arrow) processes between the ground state (GS), excited state (ES), and metastable state (MS). e Top panel: optical and microwave sequence of pulsed optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) measurements. Bottom panel: ODMR spectra of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects measured at a series of perpendicularly applied external magnetic fields Bext. f Top panel: optical and microwave sequence of spin relaxometry measurements. Bottom panel: a set of spin relaxometry data of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects showing spin dependent photoluminescence measured as a function of delay time t. The external magnetic field is 185 G applied along the out-of-plane direction, and the measurement temperature is 295 K.

We now utilize wide-field microscopy to demonstrate optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) and spin relaxation of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) defect centers (see Methods for details). The top panel of Fig. 1e shows the optical and microwave measurement sequence. We utilize 1-\({{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\)s-long green laser pulses for spin initialization and readout, and ~100-ns-long microwave \(\pi\) pulses54 to induce spin transitions of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects. We sweep the frequency f of the microwave \(\pi\) pulses and measure the fluorescence across the field of view projected on a CMOS camera. When f matches the electron spin resonance (ESR) frequencies, \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects are excited to the ms = \(\pm\)1 states, which are more likely to relax through a non-radiative pathway back to the ms = 0 ground state and emit reduced PL. The bottom panel of Fig. 1e shows a series of ODMR spectra of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) defect centers measured at room temperature with different external magnetic fields Bext applied along the out-of-plane direction. For Bext = 0, the energy level of the ms = \(\pm\)1 states of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects exhibit a small separation of ~100 MHz due to the off-axial zero field splitting effect14,26,55 and the average ESR frequency equals ~3.47 GHz at room temperature14,26,28,55. For Bext \( > \) 0, the Zeeman coupling separates the ms = \(-\)1 and ms = \(+\)1 spin states by an energy gap of magnitude 2\(\widetilde{\gamma }\)Bext (see Supplementary Information Note 3 for details), where \(\widetilde{\gamma }\) denotes the gyromagnetic ratio of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) defect centers. To characterize the quantum coherence of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects, we perform spin relaxometry measurements with a measurement protocol shown in the top panel of Fig. 1f. A microsecond scale green laser pulse is first applied to initialize the \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects to the ms = 0 state. During the time delay, fluctuating magnetic fields at the ESR frequencies will accelerate spin relaxation of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects. After a delay time t, we measure the occupation probabilities of the \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects at the ms = 0 and \(\pm\)1 states by applying a microwave \(\pi\) pulse on the corresponding ESR frequencies and measuring the spin-dependent PL by a green-laser readout pulse. The bottom panel of Fig. 1f shows the integrated PL intensity of the ms = 0 and \(\pm\)1 states measured as a function of the delay time t. By fitting the data with a three-level model51,56, the spin relaxation rate \({\Gamma }_{0}\) of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects is obtained to be 39 KHz (38 KHz) for ms = 0 \(\to -\)1 (+1) transition at 295 K, consistent with previous studies16,21,55.

After demonstrating the ODMR and spin relaxometry measurement capabilities, next, we use \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects in hBN to directly image magnetic textures of an exfoliated FGT flake. Wide-field magnetometry exploits the Zeeman splitting effect of the ensembles of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) defect centers to measure the local magnetic stray fields generated from the proximate FGT flake, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. It is worth noting that the \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spins are naturally orientated along the out-of-plane direction14, serving as an ideal local sensor to investigate the magnetic dynamics and phase transition of FGT with spontaneous perpendicular anisotropy. The magnitude of the local static magnetic field Btot can be extracted as follows: Btot = \(\pi \triangle {f}_{{{{{{\rm{ESR}}}}}}}/\widetilde{\gamma }\), where \(\triangle {f}_{{{{{{\rm{ESR}}}}}}}\) characterizes the Zeeman splitting of the \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects. Subtracting the contribution from the external magnetic field Bext, the magnetic stray field BF generated from the FGT flake can be quantitatively measured. By performing spatially dependent ODMR measurements over the \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin ensembles, we are able to obtain a 2D stray field map as shown in Fig. 2b, which is measured at a temperature T = 6 K and an external magnetic field Bext = 142 G. Through well-established reverse-propagation protocols46,57,58 (see Supplementary Information Note 3 for details), we can reconstruct the corresponding magnetization 4πM map of the FGT flake, as shown in Fig. 2c. The spatially averaged magnetization of the FGT flake is 1.3 kG at 6 K, in qualitative agreement with the bulk value33. The variation of the local magnetization could result from inhomogeneities, magnetic domains, or localized defects39,59.

a Schematic illustration of quantum sensing of local stray fields BF generated from FGT by proximate \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects. b, c Two-dimensional maps of static stray field BF (b) and reconstructed magnetization 4\(\pi\)M (c) of an exfoliated FGT flake measured at 6 K with an external perpendicular magnetic field Bext of 142 G. The black and purple dashed lines in Fig. 2b outline the boundary of the FGT and hBN flake, respectively, and the scale bar is 5 \({{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\)m.

We now present systematic wide-field magnetometry results to directly image the magnetic phase transition of the FGT flake across the Curie temperature. Figure 3a–g show the reconstructed magnetization maps of the FGT flake measured with temperatures varying from 6 to 225 K and an external perpendicular magnetic field Bext of 142 G. In the low temperature regime (T \( < \) 100 K), the exfoliated FGT flake exhibits robust magnetization, as shown in Fig. 3a, b, indicating a long-range ferromagnetic order sustained by the intrinsic magnetocrystalline anisotropy of FGT. The measured FGT magnetization decreases with increasing temperature due to enhanced thermal fluctuations (Fig. 3c). When approaching the Curie temperature, the energy of thermal fluctuations becomes comparable to the exchange energy of FGT, resulting in significant suppression of the FGT magnetization (Fig. 3d). Further increasing of the temperature leads to shrinking of the magnetic domain and decreasing magnetization of the FGT flake (Fig. 3e, f). Above the Curie temperature (T = 225 K), measured magnetization disappears over the entire FGT flake area (Fig. 3g). Figure 3h summarizes the temperature-dependent evolution of the spatially averaged magnetization of the FGT flake. The magnetic moment of the FGT flake exhibits a gradual decay in the low temperature regime, followed by a dramatic drop during the ferromagnetic phase transition, in agreement with the magneto-transport characterization results (see Supplementary Information Note 2 for details). To further highlight the evolution of magnetic domains in the FGT flake, we present wide-field magnetometry results under different external magnetic fields. Figure 4a–g show a series of magnetization maps of the FGT flake measured with Bext varied from 142 G to 698 G at a fixed temperature of 178 K. Qualitatively, the FGT magnetization increases with increasing Bext and reaches a saturation value when Bext \(\ge\) 600 G. This is accompanied by the propagation of magnetic domain walls and expansion of magnetic domain taking place at the nanoscale as shown in the presented images. Figure 4h shows field dependence of the spatially averaged FGT magnetization, consistent with the variation of the anomalous Hall resistance measured in the same magnetic field regime (see Supplementary Information Note 2 for details). We note that the previously observed labyrinthine magnetic domains in FGT are not visible here due to the optical diffraction dictated spatial resolution limit35.

Reconstructed magnetization (4πM) maps of the FGT flake at Bext = 142 G and temperatures of 6 K (a), 60 K (b), 115 K (c), 162 K (d), 169 K (e), 176 K (f), and 225 K (g), respectively. The white dashed lines outline the boundary of the exfoliated FGT flake, and the scale bar is 5 \({{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\)m. h Temperature dependence of spatially averaged magnetization of the FGT flake (blue points), in agreement with the variation behavior of the normalized Hall resistance presented in arbitrary units (a. u.) (red curve). The magneto-transport results were measured in a separate FGT flake with similar thickness.

Reconstructed magnetization (4πM) maps of the FGT flake measured at 178 K with an external perpendicular magnetic field Bext of 142 G (a), 180 (b), 199 G (c), 266 G (d), 326 G (e), 399 G (f), and 698 G (g), respectively. The white dashed lines outline the boundary of the FGT flake, and the scale bar is 5 \({{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\)m. h Field dependence of spatially averaged magnetization of the FGT flake (blue points), consistent with the variation behavior of the normalized Hall resistance presented in arbitrary units (a. u.) (red curve). The magneto-transport results were measured in a separate FGT flake with similar thickness.

In addition to sensing static magnetic stray fields, the excellent quantum coherence of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects in hBN also provides the opportunity for probing fluctuating magnetic fields that are challenging to access by conventional magnetometry methods47,48,50,51,55. Lastly, we utilize the spin relaxometry method demonstrated above to probe the temperature dependence of the magnetic fluctuations in the FGT flake, revealing the intriguing physics underlying the longitudinal magnetic susceptibility and diffusive spin transport properties60,61. Fig. 5a–g show a series of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin relaxation rate maps measured with temperatures between 165 K and 223 K. Note that the background of the intrinsic relaxation rate of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) has been subtracted to highlight the contribution \({\Gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) from the fluctuating magnetic fields generated by FGT (see Supplementary Information Note 4 for details). Due to the strong perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, the minimum magnon energy of FGT is larger than the ESR frequencies of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects in our experimentally accessible magnetic field range, hence, the measured spin relaxation is driven by the longitudinal spin fluctuations of FGT, which is further related to the static longitudinal magnetic susceptibility χ0 and the diffusive spin transport constant D46,60,61. When temperature is away from the quantum critical point, magnetic fluctuations in FGT are largely suppressed due to its vanishingly small magnetic susceptibility, leading to negligible spin relaxation rate \({\Gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) defects (Fig. 5a, b). In contrast, we observed significantly enhanced spin relaxation rate during the magnetic phase transition of FGT (Fig. 5c–e), which we attribute to the increase of the magnetic susceptibility of FGT around the Curie temperature62. When T is above 200 K, spin fluctuations remain active in FGT due to the finite spin-spin correlation in the paramagnetic state63. The observed spatially varying magnetic fluctuations over the exfoliated FGT flake could be induced by inhomogeneities in magnetic susceptibility, spin diffusion constant, and exchange coupling strength. Figure 5h summarizes the temperature dependence of the spatially averaged spin relaxation rate \({\Gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) with a peak value of 36 kHz around the Curie temperature, consistent with the ferromagnetic phase transition of FGT62. Invoking a theoretical model developed in Ref. 60, the longitudinal magnetic susceptibility χ0 and spin diffusion constant D of the exfoliated FGT flake is extracted to be (1.5 ± 0.2) × 10−2 emu cm−3 Oe−1 and (1.7 ± 0.3) × 10−5 m2/s at 189 K (see Supplementary Information Note 4 for details).

a Spin relaxation maps of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects measured at temperatures of 165 K (a), 180 K (b), 189 K (c), 195 K (d), 200 K (e), 214 K (f), and 223 K (g), respectively. The ESR frequency of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects \({f}_{{{{{{\rm{ESR}}}}}}}\) is set to be approximately 1.9 GHz in these measurements with an external magnetic field Bext = 590 G. The white dashed lines outline the boundary of the FGT flake, and the scale bar is 5 \({{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\)m. h Temperature dependence of the spatially averaged spin relaxation rate \({\Gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects located directly above the FGT flake. The black dashed line marks the Curie temperature of the FGT flake.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects in hBN as a local probe to image magnetic phase transitions and spin fluctuations in the archetypical van der Waals ferromagnet FGT at the nanoscale. The spatially resolved wide-field magnetometry results reveal the characteristic evolution behavior of magnetic domains during the phase transition of FGT. By using \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin relaxometry techniques, we are also able to access the spin fluctuations in the FGT flake, whose magnitude reaches a maximum value around the Curie temperature. Our results illustrate the appreciable capability of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects hosted by hBN of investigating local magnetic properties of layered materials in van der Waals heterostructure formats. The presented measurement platform also shows optimal field sensitivity with nanoscale sensor-to-sample distance15,16,64, offering new opportunities for advancing the state of the art of existing quantum sensing technologies. While the current study is conducted using wide-field magnetometry with a spatial resolution set by the optical diffraction limit, we anticipate that the spatial sensitivity of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects could potentially reach the tens of nanometers regime by utilizing single-spin defects and developing scanning microscopy measurement schemes2,44,50,57,65,66, opening the possibility of uncovering detailed microscopic features in a broad range of 2D material systems.

Methods

Materials and device fabrication

The hBN and FGT crystals used in this study were commercially available from 2D Semiconductors. Thin samples were mechanically exfoliated onto Si/SiO2 (285 nm) substrates. hBN flakes were subsequently irradiated by Helium ions with an energy of 5 keV and a dose of 5 \(\times\) 1013 cm−2. Irradiated hBN flakes with desirable lateral shape and dimensions are selected for fabricating FGT/hBN bilayer devices. FGT/hBN stack was prepared using the standard polydimethylsiloxane stamp process67. Selected flakes were picked up one-by-one by a stamp consisting of a thin layer of polycarbonate on polydimethylsiloxane, then released onto an Au transmission line pre-patterned on a separate Si/SiO2 (285 nm) substrate. The residual polycarbonate on the device was dissolved in chloroform before measurements. All the device fabrication processes involving handling FGT flakes were performed inside a glovebox filled with argon to minimize environmental degradation. Multiple control samples have been prepared and tested to ensure the reproducibility of the presented results (see Supplementary Information Note 5 for details).

Pulsed ODMR and spin relaxometry measurements

Pulsed ODMR and spin relaxometry measurements were performed by a wide-field microscope. The prepared FGT/hBN heterostructure was positioned in a closed-cycle optical cryostat allowing for measurements from 4.5 K to 350 K. Microsecond-long green laser pulses used for spin initialization and readout were generated by an electrically driven 515-nm laser. The laser beam spot width after passing the objective was about 25 \({{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\)m \(\times\) 25 \({{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\)m, and was subsequently focused on the hBN layer. Fluorescence of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects was imaged using a CMOS camera. Pulses to drive the green laser and to trigger the camera exposure were generated by a programmable pulse generator. Continuous microwave currents were generated using Rohde & Schwarz SGS100a and/or Rohde & Schwarz SMB100a signal generators. 100-nanosecond-long microwave current pulses were generated by sending the continuous microwave currents to a microwave switch (Minicircuits ZASWA-2-50DR+) electrically controlled by a programmable pulse generator. The microwave pulses were sent through a microwave combiner (Mini-Circuits ZB3PD-63-S+) and amplified by \(+\)50 dB (Mini-Circuits ZHL-25W-63+) before being delivered to the on-chip Au stripline. The external magnetic field was generated by a cylindrical NdFeB permanent magnet attached to a scanning stage. The field sensitivity and other merits of the presented ODMR measurement platform are discussed in Supplementary Information Note 6 in detail.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All code not included in the paper are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

References

Doherty, M. W. et al. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Phys. Rep. 528, 1–45 (2013).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Koehl, W. F., Buckley, B. B., Heremans, F. J., Calusine, G. & Awschalom, D. D. Room temperature coherent control of defect spin qubits in silicon carbide. Nature 479, 84–87 (2011).

Nagy, R. et al. High-fidelity spin and optical control of single silicon-vacancy centres in silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 10, 1954 (2019).

Widmann, M. et al. Coherent control of single spins in silicon carbide at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 14, 164–168 (2015).

Childress, L. & Hanson, R. Diamond NV centers for quantum computing and quantum networks. MRS Bull. 38, 134–138 (2013).

Yao, N. Y. et al. Scalable architecture for a room temperature solid-state quantum information processor. Nat. Commun. 3, 800 (2012).

Rose, B. C. et al. Observation of an environmentally insensitive solid-state spin defect in diamond. Science 361, 60–63 (2018).

Christle, D. J. et al. Isolated spin qubits in SiC with a high-fidelity infrared spin-to-photon interface. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021046 (2017).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Ye, M., Seo, H. & Galli, G. Spin coherence in two-dimensional materials. Npj Comput. Mater. 5, 44 (2019).

Aharonovich, I., Englund, D. & Toth, M. Solid-state single-photon emitters. Nat. Photonics 10, 631–641 (2016).

Chakraborty, C., Kinnischtzke, L., Goodfellow, K. M., Beams, R. & Vamivakas, A. N. Voltage-controlled quantum light from an atomically thin semiconductor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 507–511 (2015).

Gottscholl, A. et al. Initialization and read-out of intrinsic spin defects in a van der Waals crystal at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 19, 540–545 (2020).

Healey, A. J. et al. Quantum microscopy with van der Waals heterostructures. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.03488 (2021).

Gao, X. et al. High-contrast plasmonic-enhanced shallow spin defects in hexagonal boron nitride for quantum sensing. Nano Lett. 21, 7708–7714 (2021).

Mendelson, N. et al. Coupling spin defects in a layered material to nanoscale plasmonic cavities. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106046 (2021).

Yu, P. et al. Excited-state spectroscopy of spin defects in hexagonal boron nitride. Nano Lett. 22, 3545–3549 (2022).

Mathur, N. et al. Excited-state spin-resonance spectroscopy of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) defect centers in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 13, 3233 (2022).

Baber, S. et al. Excited state spectroscopy of boron vacancy defects in hexagonal boron nitride using time-resolved optically detected magnetic resonance. Nano Lett. 22, 461–467 (2022).

Haykal, A. et al. Decoherence of \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin defects in monoisotopic hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 13, 4347 (2022).

Murzakhanov, F. F. et al. Electron-nuclear coherent coupling and nuclear spin readout through optically polarized \({V}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}^{-}\) spin states in hBN. Nano Lett. 22, 2718–2724 (2022).

Tran, T. T., Bray, K., Ford, M. J., Toth, M. & Aharonovich, I. Quantum emission from hexagonal boron nitride monolayers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 37–41 (2016).

Grosso, G. et al. Tunable and high-purity room temperature single-photon emission from atomic defects in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 8, 705 (2017).

Su, C. et al. Tuning colour centres at a twisted hexagonal boron nitride interface. Nat. Mater. 21, 896–902 (2022).

Gottscholl, A. et al. Spin defects in hBN as promising temperature, pressure and magnetic field quantum sensors. Nat. Commun. 12, 4480 (2021).

Xu, X. et al. Creating quantum emitters in hexagonal boron nitride deterministically on chip-compatible substrates. Nano Lett. 21, 8182–8189 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Temperature-dependent energy-level shifts of spin defects in hexagonal boron nitride. ACS Photonics 8, 1889–1895 (2021).

Yankowitz, M. et al. Tuning superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 363, 1059–1064 (2019).

Jiang, S., Shan, J. & Mak, K. F. Electric-field switching of two-dimensional van der Waals magnets. Nat. Mater. 17, 406–410 (2018).

Huang, B. et al. Electrical control of 2D magnetism in bilayer CrI3. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 544–548 (2018).

Sanchez-Yamagishi, J. D. et al. Helical edge states and fractional quantum Hall effect in a graphene electron–hole bilayer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 118–122 (2017).

Deng, Y. et al. Gate-tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in two-dimensional Fe3GeTe2. Nature 563, 94–99 (2018).

Tu, Z. et al. Ambient effect on the Curie temperatures and magnetic domains in metallic two-dimensional magnets. Npj 2D Mater. Appl. 5, 62 (2021).

Fei, Z. et al. Two-dimensional itinerant ferromagnetism in atomically thin Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Mater. 17, 778–782 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Current-driven magnetization switching in a van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw8904 (2019).

Yang, M. et al. Creation of skyrmions in van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2 on (Co/Pd)n superlattice. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb5157 (2020).

Alghamdi, M. et al. Highly efficient spin-orbit torque and switching of layered ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Nano Lett. 19, 4400–4405 (2019).

Zhang, K. et al. Gigantic current control of coercive field and magnetic memory based on nanometer‐thin ferromagnetic van der Waals Fe3GeTe2. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004110 (2021).

Xu, J., Phelan, W. A. & Chien, C.-L. Large anomalous Nernst effect in a van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Nano Lett. 19, 8250–8254 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. Néel-type skyrmion in WTe2/Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 11, 3860 (2020).

Lenz, T. et al. Imaging topological spin structures using light-polarization and magnetic microscopy. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 024040 (2021).

Tetienne, J.-P. et al. Quantum imaging of current flow in graphene. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602429 (2017).

Ku, M. J. H. et al. Imaging viscous flow of the Dirac fluid in graphene. Nature 583, 537–541 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Revealing room temperature ferromagnetism in exfoliated Fe5GeTe2 flakes with quantum magnetic imaging. 2D Mater. 9, 025017 (2022).

McLaughlin, N. J. et al. Quantum imaging of magnetic phase transitions and spin fluctuations in intrinsic magnetic topological nanoflakes. Nano Lett. 22, 5810–5817 (2022).

Andersen, T. I. et al. Electron-phonon instability in graphene revealed by global and local noise probes. Science 364, 154–157 (2019).

Kolkowitz, S. et al. Probing Johnson noise and ballistic transport in normal metals with a single-spin qubit. Science 347, 1129–1132 (2015).

McCullian, B. A. et al. Broadband multi-magnon relaxometry using a quantum spin sensor for high-frequency ferromagnetic dynamics sensing. Nat. Commun. 11, 5229 (2020).

Finco, A. et al. Imaging non-collinear antiferromagnetic textures via single spin relaxometry. Nat. Commun. 12, 767 (2021).

Du, C. et al. Control and local measurement of the spin chemical potential in a magnetic insulator. Science 357, 195–198 (2017).

Burch, K. S., Mandrus, D. & Park, J.-G. Magnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals materials. Nature 563, 47–52 (2018).

Zhang, X.-Y. et al. ac Susceptometry of 2D van der Waals magnets enabled by the coherent control of quantum sensors. PRX Quantum 2, 030352 (2021).

Fuchs, G. D., Dobrovitski, V. V., Toyli, D. M., Heremans, F. J. & Awschalom, D. D. Gigahertz dynamics of a strongly driven single quantum spin. Science 326, 1520–1522 (2009).

Gottscholl, A. et al. Room temperature coherent control of spin defects in hexagonal boron nitride. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf3630 (2021).

van der Sar, T., Casola, F., Walsworth, R. & Yacoby, A. Nanometre-scale probing of spin waves using single electron spins. Nat. Commun. 6, 7886 (2015).

Thiel, L. et al. Probing magnetism in 2D materials at the nanoscale with single-spin microscopy. Science 364, 973–976 (2019).

Broadway, D. A. et al. Imaging domain reversal in an ultrathin van der Waals ferromagnet. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003314 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Patterning-Induced ferromagnetism of Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals materials beyond room temperature. Nano Lett. 18, 5974–5980 (2018).

Flebus, B. & Tserkovnyak, Y. Quantum-impurity relaxometry of magnetization dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 187204 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Noninvasive measurements of spin transport properties of an antiferromagnetic insulator. Sci. Adv. 8, eabg8562 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Characteristics and temperature-field-thickness evolutions of magnetic domain structures in van der Waals magnet Fe3GeTe2 nanolayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 192403 (2020).

Brown, P. J., Ziebeck, K. R. A., Déportes, J. & Givord, D. Magnetic correlation in itinerant magnetic materials above TC (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 55, 1881–1886 (1984).

Guo, N.-J. et al. Generation of spin defects by ion implantation in hexagonal boron nitride. ACS Omega 7, 1733–1739 (2022).

Pelliccione, M. et al. Scanned probe imaging of nanoscale magnetism at cryogenic temperatures with a single-spin quantum sensor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 700–705 (2016).

Song, T. et al. Direct visualization of magnetic domains and moiré magnetism in twisted 2D magnets. Science 374, 1140–1144 (2021).

Purdie, D. G. et al. Cleaning interfaces in layered materials heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 9, 5387 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eric E. Fullerton for providing the Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) for electrical transport measurements and Yuxuan Xiao for assistance in sample preparation and magnetometry characterization. The authors thank Shu Zhang for insightful discussions. J. Z., H. L., N. J. M., H. W., and C. R. D. were supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award FA9550−20-1-0319 and its Young Investigator Program under award FA9550-21-1-0125. M. H., S. L., D. D., and C. R. D. acknowledged the support from U. S. National Science Foundation (NSF) under awards ECCS-2029558 and DMR-2046227. M. A. and J. S. were supported by NSF under the award ECCS-2051450.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. performed the optical measurements and analyzed the data with H.L., N.M., S.L., and H.W.J.Z. and D.D. prepared the devices with assistance from M.A. and J.S.D.C. performed ion implantations. C.R.D. supervised this project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, M., Zhou, J., Chen, D. et al. Wide field imaging of van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2 by spin defects in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat Commun 13, 5369 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33016-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33016-2

This article is cited by

-

Quantum sensing with spin defects in boron nitride nanotubes

Nature Communications (2025)

-

A single spin in hexagonal boron nitride for vectorial quantum magnetometry

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Magnetic microscopy for operando imaging of battery dynamics

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Single nuclear spin detection and control in a van der Waals material

Nature (2025)

-

Critical fluctuations and noise spectra in two-dimensional Fe3GeTe2 magnets

Nature Communications (2025)