Abstract

Ultrasmall copper nanoclusters have recently emerged as promising photocatalysts for organic synthesis, owing to their exceptional light absorption ability and large surface areas for efficient interactions with substrates. Despite significant advances in cluster-based visible-light photocatalysis, the types of organic transformations that copper nanoclusters can catalyze remain limited to date. Herein, we report a structurally well-defined anionic Cu40 nanocluster that emits in the second near-infrared region (NIR-II, 1000−1700 nm) after photoexcitation and can conduct single-electron transfer with fluoroalkyl iodides without the need for external ligand activation. This photoredox-active copper nanocluster efficiently catalyzes the three-component radical couplings of alkenes, fluoroalkyl iodides, and trimethylsilyl cyanide under blue-LED irradiation at room temperature. A variety of fluorine-containing electrophiles and a cyanide nucleophile can be added onto an array of alkenes, including styrenes and aliphatic olefins. Our current work demonstrates the viability of using readily accessible metal nanoclusters to establish photocatalytic systems with a high degree of practicality and reaction complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the use of atomically precise coinage-metal nanoclusters in catalytic applications has grown rapidly due to their discrete energy levels, unique electronic configurations, and structure-dependent activities1,2,3,4,5. With energy quantization manifested in a low energy gap6, nanosized metal clusters typically exhibit a light absorption ability spanning the ultraviolet to visible or even near-infrared ranges7,8,9, making them potentially effective photosensitizers for the development of photoinduced organic transformations10,11. Despite significant progress in cluster-based photocatalysis involving reactive oxygen species12,13,14,15, other types of photoinduced coupling reactions, particularly those requiring transition metals to facilitate bond-forming elementary steps, remain difficult to achieve16. It is envisioned that copper nanoclusters may become suitable catalyst candidates for advancing this research direction11,17,18,19, mainly because copper is one of the earth-abundant metals and is capable of promoting various carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bond formation via radical recombination pathways20,21,22,23,24,25.

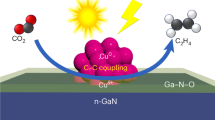

In recent years, diverse photoactive copper(I) complexes have been exploited to enable radical cross-coupling reactions by modulating either X-type ligands originating from external nucleophiles21,26,27 or L-type nitrogen/phosphorous-donor ligands (Fig. 1a)23,28,29. In order to improve the synthetic utility of visible-light photocatalysis, the latter strategy, which permits the incorporation of a variety of nucleophiles in the coupling processes, is increasingly employed30,31. Regarding the design of cluster-based photocatalysts, external carbazolide (X-type) ligands have been utilized to generate photoactive copper(I) species that facilitate the Ullmann C–N coupling of aryl halides (Fig. 1b)32. However, without the prior coordination of specific nucleophiles, the majority of emissive copper nanoclusters, which are either cationic33,34,35 or neutral36,37,38, cannot initiate single-electron transfer with electrophiles to produce organic radicals under visible-light irradiation conditions. Due to their potentially enhanced reducing ability in photoexcited states, we anticipated that emissive anionic copper nanoclusters could serve as suitable photoredox catalysts for developing visible-light-induced radical coupling reactions with broad substrate scope without the need for pre-activation with external nucleophiles.

In this study, 2,4-dimethylbenzenethiolate (2,4-DMBT) is employed as a protecting ligand to synthesize a highly scalable anionic Cu40 nanocluster, [Cu40H17(2,4-DMBT)24](PPh4) (denoted as Cu40-H NC), with excellent air and moisture stability (Fig. 1c). Structural analysis suggests a helical arrangement of tessellated polyhedral units surrounding a tetrahedral Cu4 core, which confers a C3 axis on the new nanocluster. Importantly, intrinsically photoactive Cu40-H NC with strong light absorption from UV to visible regions can efficiently promote electron-transfer-mediated three-component cyanofluoroalkylation reactions of alkenes, fluoroalkyl iodides, and trimethylsilyl cyanide under blue-LED (456 nm) irradiation. The nanocluster-based photocatalytic process is compatible with a wide range of alkenes and fluoroalkyl iodides and tolerates a variety of functional groups.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of photoactive copper nanoclusters

The air- and moisture-stable Cu40 nanocluster was synthesized by directly reducing [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6 with NaBH4 in the presence of 2,4-dimethylbenzenethiol (2,4-DMBTH) and tetraphenylphosphonium bromide (PPh4Br) under ambient conditions. Other less sterically hindered benzenethiols and aliphatic thiols, such as 4-methylbenzenethiol and 2-phenylethanethiol, failed to produce Cu40 nanoclusters, highlighting the significance of weak interactions from 2,4-DMBT in the nanocluster formation. After one week of slow vapor diffusion of hexanes into a dichloromethane-toluene solution, dark red crystals of Cu40-H NC suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) measurements were obtained on a gram scale in a high yield of 60% (based on Cu) (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Elemental mapping shows that Cu, S, and P elements are uniformly distributed throughout its block-like crystals (Supplementary Fig. 3).

According to the SCXRD analysis, Cu40-H NC crystallizes in the monoclinic P21/c space group with a pair of enantiomers, each of which contains 40 copper atoms, 24 2,4-DMBT ligands, and one tetraphenylphosphonium cation (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4). The total structure of Cu40-H NC racemates and their packing mode in the same crystal are depicted in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6. The Cu40 kernel and its protective thiolate shell share the same C3 axis which passes through the central copper atom (Fig. 2b). As illustrated in Fig. 2c, the kernel structure can be divided into three primary components: a Cu28 motif resembling a double three-bladed propeller (right), a Cu9 hexagonal pedestal (left), and a belt-like Cu3 unit (middle). The C3-symmetrical Cu28 motif is viewed as a tessellated polyhedron with a tetrahedral Cu4 core at its center (Fig. 2d). At the top of the copper nanocluster, there are three rhombic pyramid-shaped Cu5 units sharing the same vertex atom with the Cu4 tetrahedron (Fig. 2e). The remaining three vertices at the bottom of the Cu4 tetrahedron connect three twisted rhombohedral Cu6 units in the same layer, each of which shares another vertex with one of the rhombic pyramids (Fig. 2f). The average Cu−Cu distances in the tetrahedral, rhombic pyramidal, and rhombohedral building units are 2.76, 2.88, and 2.67 Å, respectively35,39. The pedestal-shaped Cu9 unit with an average Cu−Cu distance of 2.74 Å produces an equilateral triangle at its central position; each vertex of the triangle is capped by two additional copper atoms (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 7). The three copper atoms at the waist are positioned above the square faces of the trigonal prism formed by connecting the Cu28 and Cu9 units (Fig. 2h, i).

a Total structure of Cu40-H NC. b Cu40 kernel and ligand arrangements with a C3 axis. c Structure anatomy of the kernel with a side view. d Tetrahedral Cu4 unit of the Cu28 motif viewed from the front. e Adding three rhombic pyramids to the central vertex of the Cu4 tetrahedron. f Adding three rhombohedra based on three edges formed by the vertices of the tetrahedron and rhombic pyramids. g Cu9 hexagonal pedestal viewed from the back. h Connecting the central atoms of the hexagonal pedestal to the three vertices of the tetrahedron to generate a Cu6 trigonal prism. i Capping the square faces of the trigonal prism with three copper atoms at the waist. Color labels: Cu, violet, magenta, blue, light blue, and orange; S, yellow; C, gray. All hydrogen atoms and the phosphonium cation are omitted for clarity.

The surface thiolate ligands can be classified into four groups based on their distribution in the protective shell. Three identical ligand groups composed of seven thiolates stabilize the kernel structure by connecting the three primary components as well as the building units within the Cu28 motif. The aryl substituents of each group are assembled via π−π stacking and C−H···π interactions (Supplementary Fig. 8). The fourth group, which consists of the remaining three thiolates in the shell, shields the copper atoms on the hexagonal pedestal. The characteristic C−H···π interactions40 are identified in the trimeric ligand assembly (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Due to the low electron density surrounding hydrogen atoms, it is difficult to determine their exact number and positions in the crystal lattice through SCXRD. Therefore, electrospray ionization time-of-flight (ESI-TOF) mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometry, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis were employed to further characterize the hydrides in the copper nanocluster. As shown in Fig. 3a, Cu40-H NC features a monoanionic peak at m/z = 5851.28 Da (cal. 5851.31 Da) in the ESI-TOF mass spectrum, confirming the presence of [Cu40H17(2,4-DMBT)24]− anion. The counterion (PPh4+) was also successfully identified by ESI-TOF mass spectrometry in a positive mode and 31P NMR studies (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). The deuteride analogue [Cu40D17(2,4-DMBT)24](PPh4) (denoted as Cu40-D NC) was prepared using the same procedure as Cu40-H NC, with the exception that NaBD4 was utilized in place of NaBH4. As predicted, the ESI-TOF mass spectrum of Cu40-D NC displays a major signal at m/z = 5868.46 Da (cal. 5868.45 Da), which corresponds to the [Cu40D17(2,4-DMBT)24]− anion (Fig. 3b). The m/z difference between [Cu40H17(2,4-DMBT)24]− and [Cu40D17(2,4-DMBT)24]− (5868.46 − 5851.28 = 17.18) reveals that the Cu40 nanocluster contains 17 hydrides41. Moreover, five distinct 2H NMR signals ranging from 5.05 to −1.67 ppm in the spectrum of Cu40-D NC but not in that of Cu40-H NC support the existence of hydride species in the cluster (Supplementary Fig. 12).

a, b ESI-TOF mass spectra of Cu40-H NC (a) and Cu40-D NC (b) in a negative mode. c A front view of the DFT-optimized structure for [Cu40H17(SCH3)24]−. d Distributions of hydride ligands in various coordination modes viewed from the back. e Seven μ3-H ligands caping the triangular faces. f Four μ4-H ligands in the tetrahedral units. g Three μ4-H ligands in the rhombohedral units. h Three μ5-H ligands in the square pyramidal units. Color labels: Cu, violet; S, yellow; C, gray; protons, white; hydrides, red. Exp., experimental data; Cal., calculated mass distributions based on the cluster’s formula. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To precisely determine the geometric positions of the 17 hydrides in Cu40-H NC, DFT calculations were performed on the basis of the symmetry of the entire kernel as well as the four types of copper hydride species identified by SCXRD (Supplementary Fig. 4)42,43. Through the optimizations involving the simplification of 2,4-DMBT ligands to SCH3 groups, 17 hydrides with seven distinct coordination environments were successfully assigned to the [Cu40H17(SCH3)24]− anion (Fig. 3c), producing a single C3 axis in their symmetrical distributions. The capping hydrides (μ3-H) and interstitial hydrides (μ4-H and μ5-H) are clearly discernible in Fig. 3d. The seven μ3-H ligands bind to seven Cu3 triangles with Cu–H distances in the range of 1.64–1.80 Å44. One triangle remains at the center of the hexagonal pedestal; three stay in the layer between the Cu9 pedestal and the Cu28 polyhedral motif; three connect the Cu5 rhombic pyramids and the Cu6 rhombohedra within the Cu28 motif (Fig. 3e). As illustrated in Fig. 3f, there is one μ4-H ligand in the central Cu4 tetrahedron and three in the grooves between the base of the Cu28 motif and the belt-like Cu3 unit. In the three rhombohedra, three additional μ4-type interstitial hydrides are located in close proximity to the faces shared with the central tetrahedron (Fig. 3g). The Cu–H bond lengths in the μ4-coordination mode range from 1.66 to 1.91 Å. Lastly, the three μ5-H ligands are found in the cavity of three square pyramids which are constructed by the kernel atoms in the Cu28 motif (Fig. 3h), with an average Cu–H bond length of 1.88 Å.

In accordance with the optimized cluster structure, we computed the projected density of states (PDOS) curves45. As displayed in Supplementary Fig. 13, the copper atomic orbital components contribute the most to the total density of states in the energy range between −7.5 and 1.0 eV, showing copper electron delocalization in the frontier orbitals of Cu40-H NC. In the experimental UV–Vis absorption spectrum, Cu40-H NC exhibits the three major absorption peaks at 378, 429, and 510 nm, which corresponds well with the calculated data (Fig. 4a). The theoretical analysis of the electronic transitions and atomic components is further illustrated using a Kohn−Sham orbital energy diagram (Supplementary Fig. 14). All three spectral features are primarily associated with the Cu 3d → Cu 4s interband transitions and the ligand-to-metal charge-transfer (LMCT) transitions mixed with d → s/p metal-cluster-centered transitions46. The HOMO−LUMO gap is estimated to be 2.8 eV (Supplementary Fig. 15), which is comparable to previously reported data for copper nanoclusters47. In addition, the time-dependent UV–Vis absorption spectra suggest that Cu40-H NC is stable in various organic solvents, including dichloromethane, acetonitrile, and N,N-dimethylacetamide (Supplementary Figs. 16–18).

a Experimental (purple line) and calculated (blue line) UV–Vis absorption spectra of Cu40-H NC. b Excitation (emission wavelength: 1000 nm) and emission (excitation wavelength: 600 nm) spectra of Cu40-H NC in dichloromethane under N2 or air atmosphere. c Emission decay (λmax = 1000 nm) of photoexcited Cu40-H NC at room temperature. d TA data maps pumped at 400 nm in dichloromethane. e Species-associated spectra (from global fit analysis). f Stern–Volmer plot for the luminescence quenching of Cu40-H NC with various concentrations of C4F9I. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Encouragingly, the copper nanocluster exhibits NIR-II emission35 in a N2-purged dichloromethane solution, with two distinct peaks at 1000 and 1174 nm, respectively (Fig. 4b). The significant decrease in emission observed upon exposing Cu40-H NC to air is highly indicative of triplet-state photoexcitations48. As shown in Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 19, the double-exponential fitting on the photoluminescence decay signals of Cu40-H NC collected by time-correlated single photon counting techniques reveals two lifetime components of 1.18 μs (40.8%) and 8.82 μs (59.2%). To further understand the excited-state dynamics of Cu40-H NC in different solvents, femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) experiments were performed upon excitation with 400-nm laser pulse (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 20). Based on the sequential model, the global analysis yields evolution-associated difference spectra for four major components with lifetimes ranging from 0.20 ps to > 3.0 ns, which can be categorized as three excited-state absorption (ESA) signals and one ground-state bleaching (GSB) signal (Fig. 4f). Within the first 0.6 ps, the primary ESA peak redshifts from 500 to 600 nm, suggesting the generation of the first singlet excited state from a higher excited state via internal conversion35. The following intersystem crossing process begins at about 3 ps and involves a redshift of the ESA signal from 600 to 650 nm, resulting in the formation of an triplet LMCT state48. Subsequently, an additional process with a lifetime of 276.1 ps occurs, which could be attributed to the structural relaxation of Cu40-H NC’s metal core35. Lastly, the GSB signal around 650 nm endures until the end of the time-delay window (3 ns), which indicates the emergence of a long-lived species (Supplementary Fig. 21). The corresponding decay process gives rise to the phosphorescence emission. fs-TA measurements in other solvents show similar decay pathways after excitation (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). The rapid structural relaxation of Cu40-H NC in toluene, as compared to dichloromethane and N,N-dimethylacetamide, can be readily explained by the fact that nonpolar solvents exert a weaker stabilizing effect on the triplet LMCT state of the nanocluster49.

To determine whether photoexcited Cu40-H NC is capable of reducing fluoroalkyl iodide electrophiles, an important class of chemical reagents used to produce valuable fluorine-containing molecules for agricultural and pharmaceutical industries26, we first measured the cyclic voltammogram of Cu40-H NC under inert atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 25). Based on the higher-energy shoulder (around 1077 nm) in its emission spectrum at an excitation wavelength of 456 nm, the photoexcited redox potential of Cu40-H NC is estimated to be −1.73 V (vs. Fc+/Fc), suggesting feasible electron transfer processes with C4F9I (Ep/2 = −1.65 V vs. Fc+/Fc, see Supplementary Fig. 26). We have also established that C4F9I efficiently quenches the luminescence of Cu40-H NC (Supplementary Fig. 27); the Stern–Volmer plot provides a quenching constant (KSV) of 0.38 mM−1 (Fig. 4f). The quenching experiments strongly support the activation of perfluoroalkyl iodides by the copper nanocluster at its photoexcited states. Importantly, the powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Cu40-H NC remain unchanged under ambient conditions for more than two months (Supplementary Fig. 28).

Photocatalytic performances

On account of its favorable optical properties, matched photoexcited redox potential, and high stability, Cu40-H NC is considered as a potential photocatalyst for promoting visible-light-driven organic transformations. Since perfluoroalkyl groups can significantly increase the lipophilicity, bioavailability, and metabolic stability of bioactive compounds28, it is highly desirable to develop efficient visible-light photocatalysis based on copper nanoclusters for the cyanofluoroalkylation of various alkenes with readily available fluoroalkyl iodides50,51,52. After examining a variety of reaction parameters, we identified a procedure that enables the desired three-component cyanofluoroalkylation (Table 1, entry 1; 78% yield). Control experiments demonstrate the importance of Cu40-H NC, base, water, and light in the coupling reaction (entries 2–5). Notably, no product (1) was obtained at an elevated temperature in the absence of light (entry 6). Irradiation with blue-LED lamps at wavelengths of 427–467 nm results in high yields of 1 (entries 7 and 8), whereas no reaction occurs when exposed to 520-nm green-LED light (entry 9). Using cationic or neutral copper nanoclusters53,54 instead of anionic Cu40-H NC has a direct negative impact on cluster-based photocatalysis (entries 10 and 11). The replacement of Cu40-H NC with a variety of Cu(I) and Cu(II) sources leads to a dramatic decrease in product yields, showing the superior photocatalytic activity of Cu40-H NC in the visible-light-mediated cyanofluoroalkylation (entries 12–18). The catalytic efficiency of the cluster precursors, including those with ligands or phosphonium salts added, is significantly lower than that of Cu40-H NC (entries 12–15). When the catalyst loading was reduced to 0.15 mol%, the reaction furnished the desired product in a satisfactory yield, with a turnover number (TON) of 440 (entry 19). Despite high reaction efficiency in acetonitrile (entry 20), other organic solvents, such as 1,2-dichloroethane, dimethylsulfoxide, and toluene, gave much lower yields (entry 21). Several other alkyl amines can also serve as base additives in this photocatalysis (entries 22–24), but they are not as effective as DIPEA. The addition of a non-reducing inorganic base, such as K3PO4, promotes the radical coupling (entry 25), indicating that the direct single-electron reduction of C4F9I by photoexcited Cu40-H NC is operative. Increasing the amount of water from two to four equivalents lowers the yield by less than 10% (entry 26), which suggests that the coupling is highly compatible with water. Similar to many photoinduced copper(I)-catalyzed radical reactions23,55,56, the coupling enabled by Cu40-H NC cannot proceed under an atmosphere of air (entry 27).

Under the optimized reaction conditions, a broad range of alkenes can be double-functionalized in high isolated yields (Fig. 5). In addition to 1- and 2-vinylnaphthalenes, a wide range of styrenes containing an electron-donating or -withdrawing functional group at the para-, meta-, or ortho-position of the aromatic ring perform well in the cyanofluoroalkylation, with TONs of up to 320 (Fig. 5, products 1–22). Despite the fact that a similar transformation mediated by copper(I) complexes occurred under violet light irradiation51, the olefin substrates are mostly restricted to electron-rich styrenes, with trace amounts of products resulting from strongly electron-deficient styrenes (Fig. 5, products 7 and 18). Importantly, the cluster-based visible-light photocatalysis is tolerant of many heterocycles including pyridines, indoles, benzofurans, and benzothiophenes (Fig. 5, products 23–26). It is noteworthy that, the scope of alkene substrates is not limited to styrenes; a variety of nonconjugated alkenes are also suitable reaction partners (Fig. 5, products 27–31). Benzoyl ester and aniline derivatives as well as sterically hindered aliphatic alkenes afford the desired products in synthetically useful yields.

Reaction conditions: alkene (0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), fluoroalkyl iodide (3.0 equiv.), TMSCN (3.0 equiv.), Cu40-H NC (0.3 mol%), DIPEA (4.0 equiv.), and H2O (2.0 equiv.) in anhydrous DMA (1.0 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature with blue-LED light irradiation (456 nm) for 20 h. For each entry number (in bold), data are reported as isolated yields. TMSCN, trimethylsilyl cyanide; DIPEA, N,N-diisopropylethylamine; DMA, N,N-dimethylacetamide; tBu, tert-butyl; Ac, acetyl; Boc, tert-butoxycarbonyl; Bz, benzoyl; Ts, p-toluenesulfonyl.

With regard to the electrophile scope, a number of linear and branched perfluoroalkyl iodides, including trifluoromethyl iodide, are found to be highly reactive (Fig. 5, products 32–36). Under the standard reaction conditions, α,α-difluoro carbonyl compounds can be successfully prepared without the use of any external oxidants (Fig. 5, products 37–41), demonstrating the practicality of this cluster-based approach in organic synthesis.

To further illustrate the robustness of Cu40-H NC in visible-light photocatalysis, we chose an α-bromo isobutyric ester as an electrophile partner in the three-component radical coupling, resulting in a satisfactory yield of cyanated product 42 (Fig. 6a). This class of bromide electrophiles were underdeveloped in previous copper-based photocatalytic systems50,51. Furthermore, no two-component bromoalkylation of alkenes occurred in the absence of a catalyst. Given that only a small amount of iodofluoroalkylated products were observed upon substituting C4F9I for the bromide electrophile (Table S4)57, we concluded that the formation of an electron donor–acceptor complex58,59 may not be the primary mechanism by which electrophiles are activated to produce alkyl radicals in this cluster-based photocatalysis. A radical-clock experiment with a cyclopropyl-substituted alkene clearly implies a radical addition into the double bond prior to the copper-mediated cyanation process (Fig. 6b).

Based on the ESI-TOF mass data of the reaction mixture (Supplementary Fig. 29) and the UV–Vis absorption spectrum of the recycled catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 30), it can be determined that Cu40-H NC remains largely intact throughout the photocatalytic process. Given that both DIPEA and water are critical to the cyanoalkylation, we propose a catalytic cycle involving the activation of TMSCN under the basic conditions (Fig. 6c). Upon exposure to blue-LED light, photoexcited Cu40-H NC undergoes single-electron transfer with an alkyl halide to produce a mixed-valence cluster intermediate, a reactive alkyl radical (R’•), and an iodide anion. The subsequent trapping of R’• by a terminal alkene generates a secondary alkyl radical (R”•) for further copper-mediated functionalization processes. In the presence of DIPEA and water, the neutral mixed-valence cluster intermediate reacts with TMSCN to yield a anionic cyanide-ligated cluster intermediate and trimethylsilanol with a strong Si–O single bond30. The radical recombination between R”• and the cyanide-ligated cluster intermediate affords the C–C coupling product and regenerates the original copper(I) nanocluster60,61,62. The high photostability of Cu40-H NC in the presence of DIPEA excludes the possibility of the amine base acting as a sacrificial reagent to reduce the photoexcited copper nanocluster (Supplementary Fig. 31).

We present here the synthesis and characterization of an atomically precise Cu40 nanocluster in a C3 symmetry, which is the first example of anionic copper nanoclusters with NIR-II emission. Due to its wide optical absorption range and excellent reducing ability in its photoexcited states, this stable 2,4-DMBT-protected copper(I) cluster can be employed as a highly effective photoredox catalyst for the cyanofluoroalkylation of alkenes. Beyond providing the first cluster-catalyzed three-component radical coupling, we have discovered that the current method has a fairly broad substrate scope under blue-LED irradiation conditions. Further efforts are being made to investigate other types of visible-light-driven radical reactions with cheap and scalable nanocluster catalysts for sustainable and practical organic synthesis.

Methods

General considerations

Unless otherwise noted, materials were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received. Tetrakis(acetonitrile)copper(I) hexafluorophosphate ([Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6, 98%) and tetraphenylphosphonium bromide (PPh4Br, 98%) were purchased from Leyan Co., Ltd. Sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 99.8% purity) and sodium borohydride-d4 (NaBD4, 98% purity) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 2,4-dimethylbenzenethiol (2,4-DMBTH, 98% purity) was purchased from Saan Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. Methanol (>99% purity), dichloromethane (>99% purity), toluene (>99% purity), hexanes (>99% purity), and acetonitrile (>99% purity) were purchased from Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.

X-ray diffraction data of the crystal was collected using synchrotron radiation (λ = 0.67043 Å) on beamline 17B1 at the National Facility for Protein Science Shanghai in the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. The diffraction data reduction and integration were performed by the HKL3000 software. Powder X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded on a Rigaku Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer (CuKα, λ = 1.5418 Å), operating at 40 kV and 30 mA. The measurement parameters included a scan speed of 10° min−1, a step size of 0.05°, and a scan range of 2θ from 3° to 50°.

Scanning electron microscope images and energy dispersive spectroscopy mapping were collected on an EM-30 AX PLUS microscope (South Korea, COXEM company).

ESI-TOF mass spectrometry data were recorded on a Waters Q-TOF mass spectrometer using a Z-spray source. High-resolution ESI mass measurements were performed on a Bruker impact II high-resolution LC-QTOF mass spectrometer.

All UV−Vis absorption spectra were acquired in the 200–800 nm range using a Cary 3500 spectrophotometer (Agilent). Steady-state emission spectra were obtained on an Edinburgh FLS1000 spectrophotometer.

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 500 (500 MHz) or Bruker 400 (400 MHz) spectrometer in chloroform-d. Chemical shifts were quoted in parts per million (ppm) referenced to 0.0 ppm of tetramethyl silane. 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 500 or Bruker 400 spectrometer in chloroform-d with complete proton decoupling. 19F and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 500 or Bruker 400 spectrometer.

Cyclic voltammograms were performed on a CHI760E electrochemistry workstation. Regular 3-electrode systems were used. Measurements were recorded in an acetonitrile solution of Bu4NClO4 (0.1 M) at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1 under the protection of N2 using a glassy carbon disk (d = 0.3 cm) as a working electrode and a platinum plate (1 cm × 1 cm) as a counter electrode. An Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) electrode was used as a reference electrode in all the experiments, and its potential (0.46 V vs. Fc+/Fc) was calibrated with the ferrocenium/ferrocene (Fc+/Fc) redox couple.

Synthesis of Cu40H17(2,4-DMBT)24](PPh4) nanocluster

[Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6 (50 mg, 0.13 mmol) and PPh4Br (20 mg, 0.048 mmol) were dissolved in acetonitrile (5 mL). Then, 2,4-DMBTH (10 μL, 0.074 mmol) was introduced to the reaction. After stirring for 10 min, freshly prepared NaBH4 (50 mg, 1.3 mmol) in an ice-cold methanol solution (5 mL) was added instantaneously. The solvent was evaporated after the reduction for 5 h, the remaining solid was dissolved in dichloromethane and filtered. Red block-like crystals of Cu40-H NC suitable for single-crystal X-ray analysis were obtained by slow vapor diffusion of hexanes into 5-mL dichloromethane-toluene (1:1 v/v) of the nanoclusters at –4 °C for one week.

Gram-scale synthesis

[Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6 (4.65 g, 12.5 mmol) and PPh4Br (1.89 g, 4.51 mmol) were dissolved in acetonitrile (450 mL). Then, 2,4-DMBTH (0.930 mL, 6.90 mmol) was introduced to the reaction. After stirring for 10 min, freshly prepared NaBH4 (4.70 g, 124 mmol) in an ice-cold methanol solution (450 mL) was added instantaneously. The solvent was evaporated after the reduction for 5 h, the remaining solid was dissolved in dichloromethane and filtered. Red block-like crystals of Cu40-H NC suitable for single-crystal X-ray analysis were obtained by slow vapor diffusion of hexanes into 400-mL dichloromethane-toluene (1:1 v/v) of the nanoclusters at −4 °C for one week.

Synthesis of Cu40D17(2,4-DMBT)24](PPh4) nanocluster

[Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6 (50 mg, 0.13 mmol) and PPh4Br (20 mg, 0.048 mmol) were dissolved in acetonitrile (5 mL). Then, 2,4-DMBTH (10 μL, 0.074 mmol) was introduced to the reaction. After stirring for 10 min, freshly prepared NaBD4 (55 mg, 1.3 mmol) in an ice-cold methanol solution (5 mL) was added instantaneously. The solvent was evaporated after the reduction for 5 h, the remaining solid was dissolved in dichloromethane and filtered. Red block-like crystals of Cu40-D NC were obtained by slow vapor diffusion of hexanes into 5-mL dichloromethane-toluene (1:1 v/v) of the nanoclusters at −4 °C for one week.

Computational studies

For the experimental complex, [Cu40H17(SR)24]– (R = 2,4-Me2C6H3), the aryl groups were replaced by the –CH3 in theoretical computations to reduce the computational cost without affecting the interfacial bond strength.

Calculations of UV–Vis absorption spectra and Kohn–Sham (K–S) molecular orbitals: Gaussian 16 package63 was used to obtain the optimized geometry by Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof hybrid functional (PBE0)64 method with Grimme’s BJ-damped variant of DFT-D3 empirical dispersion65,66. The pseudopotential basis set LANL2DZ and all-electron def2-SVP were used for Cu atoms and other atoms (H, C, and S), respectively. The time dependent density functional theory method implemented in Gaussian 16 was used to compute the simulated spectra using the same functional, empirical dispersion and basis sets as above. K–S orbital analysis was performed for identifying the atomic orbital contribution to each molecular orbital using Multiwfn 3.8 program67,68.

Based on the hydrides assigned by X-ray diffraction data, all possible positions of the hydrides in [Cu40H17(SR)24]– (R = CH3) were predicted. The energetically favored structure was then fully optimized without any constraints, and the resulting structure is the predicted final model structure shown in Fig. 3c.

TA measurements

Femtosecond transient absorption measurements were performed at room temperature using a Spectra Physics Tsunami Ti:Sapphire (Coherent; 800 nm, 150 fs, 7 mJ pulse−1, and 1 kHz repetition rate) as the laser source and a Helios spectrometer (Ultrafast Systems LLC). Briefly, the 800-nm output pulse from the regenerative amplifier was split in two parts. 95% of the output from the amplifier is used to pump a TOPAS optical parametric amplifier, which generated a wavelength-tunable laser pulse from 400 to 850 nm as pump beam in a Helios transient absorption setup (Ultrafast Systems Inc.). The 400-nm pump beam was used for the measurements. The remaining 5% of the amplified output was focused onto a sapphire crystal to generate a white-light continuum used for probe beam in our measurements (420 to 850 nm). The pump beam was depolarized and chopped at 1 kHz, and both pump and probe beams were overlapped in the sample for magic angle transient measurements. Samples were vigorously stirred in all the measurements. Species-associated spectra were obtained by fitting the principal kinetics deduced from single value decomposition analysis.

Stern−Volmer experiments

An Edinburgh FLS1000 spectrophotometer was used for luminescence quenching experiments. Linear regression of I0/I against concentration was performed in Origin. All samples for the luminescence test were prepared in the glovebox, and the measurements were performed at room temperature. Cu40-H NC solution (0.025 mM) in acetonitrile was excited at 456 nm and the emission was collected at 1077 nm. For each quenching experiment, a certain volume of the stock solution was added into a 4-mL solution of Cu40-H NC (0.025 mM) in a 10-mm quartz cuvette with a screw cap.

Procedure for cluster-based photocatalysis

To a 10-mL flame-dried Schlenk tube under N2 atmosphere were added Cu40-H NC (2.0 mg, 0.3 mol%), alkene (0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), fluoroalkyl iodide (0.30 mmol, 3.0 equiv.), TMSCN (29.8 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3.0 equiv.), DIPEA (69.7 μL, 0.40 mmol, 4.0 equiv.), H2O (3.6 μL, 0.20 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), and anhydrous DMA (1.0 mL) sequentially. The reaction mixture was irradiated by 40-watt Kessil PR160L-456 blue-LED lamps at room temperature for 20 h. After irradiation, the reaction mixture was diluted with saturated brine (10 mL) and extracted four times with ethyl acetate (4 × 5 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to afford the corresponding product.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the finding of this study are available in this article and the Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for Cu40-H NC have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition number CCDC 2263793. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Source data are provided in this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jin, R., Zeng, C., Zhou, M. & Chen, Y. Atomically precise colloidal metal nanoclusters and nanoparticles: fundamentals and opportunities. Chem. Rev. 116, 10346–10413 (2016).

Chakraborty, I. & Pradeep, T. Atomically precise clusters of noble metals: emerging link between atoms and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 117, 8208–8271 (2017).

Du, Y., Sheng, H., Astruc, D. & Zhu, M. Atomically precise noble metal nanoclusters as efficient catalysts: a bridge between structure and properties. Chem. Rev. 120, 526–622 (2020).

Xiang, H. et al. Identifying the real chemistry of the synthesis and reversible transformation of AuCd bimetallic clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14248–14257 (2022).

Wu, Q.-J. et al. Atomically precise copper nanoclusters for highly efficient electroreduction of CO2 towards hydrocarbons via breaking the coordination symmetry of Cu site. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306822 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Visible light gold nanocluster photocatalyst: selective aerobic oxidation of amines to imines. ACS Catal. 7, 3632–3638 (2017).

Takano, S. et al. Photoluminescence of doped superatoms M@Au12 (M = Ru, Rh, Ir) homoleptically capped by (Ph2)PCH2P(Ph2): efficient room-temperature phosphorescence from Ru@Au12. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 10560–10564 (2021).

Liu, L.-J. et al. Atomically precise gold nanoclusters at the molecular-to-metallic transition with intrinsic chirality from surface layers. Nat. Commun. 14, 2397 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Dynamic and transformable Cu12 cluster-based C−H···π-stacked porous supramolecular frameworks. Nat. Commun. 14, 6413 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Ligand modification of Au25 nanoclusters for near-infrared photocatalytic oxidative functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3787–3792 (2022).

Wang, Y.-M. et al. An atomically precise pyrazolate-protected copper nanocluster exhibiting exceptional stability and catalytic activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218369 (2023).

Kawasaki, H. et al. Generation of singlet oxygen by photoexcited Au25(SR)18 clusters. Chem. Mater. 26, 2777–2788 (2014).

Li, Z., Liu, C., Abroshan, H., Kauffman, D. R. & Li, G. Au38S2(SAdm)20 photocatalyst for one-step selective aerobic oxidations. ACS Catal. 7, 3368–3374 (2017).

Agrachev, M. et al. Understanding and controlling the efficiency of Au24M(SR)18 nanoclusters as singlet-oxygen photosensitizers. Chem. Sci. 11, 3427–3440 (2020).

Hirai, H. et al. Doping-mediated energy-level engineering of M@Au12 superatoms (M=Pd, Pt, Rh, Ir) for efficient photoluminescence and photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207290 (2022).

Zhu, W. et al. Atomically precise metal nanoclusters as single electron transferers for hydroborylation. Precis. Chem. 1, 175–182 (2023).

Cook, A. W., Jones, Z. R., Wu, G., Scott, S. L. & Hayton, T. W. An organometallic Cu20 nanocluster: synthesis, characterization, immobilization on silica, and “click” chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 394–400 (2018).

Nematulloev, S. et al. Atomically precise defective copper nanocluster catalysts for highly selective C−C cross-coupling reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303572 (2023).

Dong, G. et al. Multi-layer 3D chirality and double-helical assembly in a copper nanocluster with a triple-helical Cu15 core. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302595 (2023).

Jones, G. O., Liu, P., Houk, K. N. & Buchwald, S. L. Computational explorations of mechanisms and ligand-directed selectivities of copper-catalyzed Ullmann-type reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6205–6213 (2010).

Creutz, S. E., Lotito, K. J., Fu, G. C. & Peters, J. C. Photoinduced Ullmann C–N coupling: demonstrating the viability of a radical pathway. Science 338, 647–651 (2012).

Tan, Y., Muñoz-Molina, J. M., Fu, G. C. & Peters, J. C. Oxygen nucleophiles as reaction partners in photoinduced, copper-catalyzed cross-couplings: O-arylations of phenols at room temperature. Chem. Sci. 5, 2831–2835 (2014).

Xia, H.-D. et al. Photoinduced copper-catalyzed asymmetric decarboxylative alkynylation with terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 16926–16932 (2020).

Lee, H. et al. Investigation of the C–N bond-forming step in a photoinduced, copper-catalyzed enantioconvergent N–alkylation: characterization and application of a stabilized organic radical as a mechanistic probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4114–4123 (2022).

Wang, L.-L. et al. A general copper-catalysed enantioconvergent radical Michaelis–Becker-type C(sp3)–P cross-coupling. Nat. Synth. 2, 430–438 (2023).

Sagadevan, A. & Hwang, K. C. Photo-induced Sonogashira C–C coupling reaction catalyzed by simple copper(I) chloride salt at room temperature. Adv. Synth. Catal. 354, 3421–3427 (2012).

Bissember, A. C., Lundgren, R. J., Creutz, S. E., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Transition-metal-catalyzed alkylations of amines with alkyl halides: photoinduced, copper-catalyzed couplings of carbazoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 5129–5133 (2013).

He, J., Chen, C., Fu, G. C. & Peters, J. C. Visible-light-induced, copper-catalyzed three-component coupling of alkyl halides, olefins, and trifluoromethylthiolate to generate trifluoromethyl thioethers. ACS Catal. 8, 11741–11748 (2018).

Chen, C., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Photoinduced copper-catalysed asymmetric amidation via ligand cooperativity. Nature 596, 250–256 (2021).

Cho, H., Suematsu, H., Oyala, P. H., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Photoinduced, copper-catalyzed enantioconvergent alkylations of anilines by racemic tertiary electrophiles: synthesis and mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4550–4558 (2022).

Cai, Y., Chatterjee, S. & Ritter, T. Photoinduced copper-catalyzed late-stage azidoarylation of alkenes via arylthianthrenium salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13542–13548 (2023).

Sagadevan, A. et al. Visible-light copper nanocluster catalysis for the C–N coupling of aryl chlorides at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12052–12061 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Atomically precise copper cluster with intensely near-infrared luminescence and its mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 4891–4896 (2020).

Nematulloev, S. et al. [Cu15(PPh3)6(PET)13]2+: a copper nanocluster with crystallization enhanced photoluminescence. Small 17, 2006839 (2021).

Jia, T. et al. Eight-electron superatomic Cu31 nanocluster with chiral kernel and NIR-II emission. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 10355–10363 (2023).

Yang, X.-X. et al. Red-luminescent biphosphine stabilized ‘Cu12S6’ cluster molecules. Chem. Commun. 50, 11043–11045 (2014).

Eichhöfer, A., Buth, G., Lebedkin, S., Kühn, M. & Weigend, F. Luminescence in phosphine-stabilized copper chalcogenide cluster molecules–a comparative study. Inorg. Chem. 54, 9413–9422 (2015).

Li, Y.-L. et al. Cu14 cluster with partial Cu(0) character: difference in electronic structure from isostructural silver analog. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900833 (2019).

Liu, C.-Y. et al. Structural transformation and catalytic hydrogenation activity of amidinate-protected copper hydride clusters. Nat. Commun. 13, 2082 (2022).

Nan, Y. et al. Unraveling the long-pursued Au144 structure by X-ray crystallography. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat7259 (2018).

Sun, C. et al. Atomically precise, thiolated copper–hydride nanoclusters as single-site hydrogenation catalysts for ketones in mild conditions. ACS Nano 13, 5975–5986 (2019).

Lee, S. et al. [Cu32(PET)24H8Cl2](PPh4)2: a copper hydride nanocluster with a bisquare antiprismatic core. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13974–13981 (2020).

Luo, G.-G. et al. Total structure, electronic structure and catalytic hydrogenation activity of metal-deficient chiral polyhydride Cu57 nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306849 (2023).

Dhayal, R. S., van Zyl, W. E. & Liu, C. W. Polyhydrido copper clusters: synthetic advances, structural diversity, and nanocluster-to-nanoparticle conversion. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 86–95 (2016).

Sakthivel, N. A. et al. The missing link: Au191(SPh-tBu)66 Janus nanoparticle with molecular and bulk-metal-like properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15799–15814 (2020).

Lam, C.-H., Tang, W. K. & Yam, V. W.-W. Synthesis, electrochemistry, photophysics, and photochemistry of a discrete tetranuclear copper(I) sulfido cluster. Inorg. Chem. 62, 1942–1949 (2023).

Han, B.-L. et al. Polymorphism in atomically precise Cu23 nanocluster incorporating tetrahedral [Cu4]0 kernel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5834–5841 (2020).

Kong, Y.-J. et al. Achiral-core-metal change in isomorphic enantiomeric Ag12Ag32 and Au12Ag32 clusters triggers circularly polarized phosphorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19739–19747 (2022).

Glasbeek, M. & Zhang, H. Femtosecond studies of solvation and intramolecular configurational dynamics of fluorophores in liquid solution. Chem. Rev. 104, 1929–1954 (2004).

Guo, Q., Wang, M., Wang, Y., Xu, Z. & Wang, R. Photoinduced, copper-catalyzed three components cyanofluoroalkylation of alkenes with fluoroalkyl iodides as fluoroalkylation reagents. Chem. Commun. 53, 12317–12320 (2017).

Guo, Q. et al. Dual-functional chiral Cu-catalyst-induced photoredox asymmetric cyanofluoroalkylation of alkenes. ACS Catal. 9, 4470–4476 (2019).

Lu, F.-D., Lu, L.-Q., He, G.-F., Bai, J.-C. & Xiao, W.-J. Enantioselective radical carbocyanation of 1,3-dienes via photocatalytic generation of allylcopper complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4168–4173 (2021).

Liu, L.-J. et al. Mediating CO2 electroreduction activity and selectivity over atomically precise copper clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205626 (2022).

Liu, L.-J. et al. A high-nuclearity CuI/CuII nanocluster catalyst for phenol degradation. Chem. Commun. 57, 5586–5589 (2021).

Wang, P.-Z. et al. Copper-catalyzed three-component photo-ATRA-type reaction for asymmetric intermolecular C–O coupling. ACS Catal. 12, 10925–10937 (2022).

Ma, B. et al. Metal-organic framework supported copper photoredox catalysts for iminyl radical-mediated reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300233 (2023).

Xie, F., He, J. & Zhang, Y. Frustrated-radical-pair-initiated atom transfer radical addition of perfluoroalkyl halides to alkenes. Org. Chem. Front. 10, 3861–3869 (2023).

Postigo, A. Electron donor-acceptor complexes in perfluoroalkylation reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 6391–6404 (2018).

Tang, X. & Studer, A. Alkene 1,2-difunctionalization by radical alkenyl migration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 814–817 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Enantioselective cyanation of benzylic C–H bonds via copper-catalyzed radical relay. Science 353, 1014–1018 (2016).

Wang, F. et al. Enantioselective copper-catalyzed intermolecular cyanotrifluoromethylation of alkenes via radical process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15547–15550 (2016).

Drennhaus, T. et al. Enantioselective copper-catalyzed fukuyama indole synthesis from 2-vinylphenyl isocyanides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8665–8676 (2023).

Gaussian 16 Rev. A.03 (Wallingford, CT, 2016).

Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: the PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 6158–6170 (1999).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Calculation of molecular orbital composition. Acta Chim. Sinica 69, 2393–2406 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge The University of Hong Kong, the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, People’s Republic of China (RGC: 27301820, J.H., 17313922, J.H.), the Croucher Foundation, the Innovation and Technology Commission (HKSAR, China), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22201236, J.H.) for their financial support. We also thank S.-Q. Zang, X.-J. Zhai, and the staff of BL17B1 beamline at the National Facility for Protein Science of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for assistance during data collection. V.W.-W.Y. acknowledges support from the Key Program of the Major Research Plan on “Architectures, Functionalities and Evolution of Hierarchical Clusters” of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 91961202, V.W.-W.Y.). Publication made possible in part by support from the HKU Libraries Open Access Author Fund sponsored by the HKU Libraries.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.-J.L. synthesized the copper nanoclusters and conducted most of the experiments for characterization, with assistance from Y.L. M.-M.Z. optimized the photocatalytic reaction conditions. Z.D. and D.L.P. collected and analyzed the data from transient absorption measurements, and L.-L.Y. performed SCXRD experiments. V.W.-W.Y. provided insights into cluster characterization and mechanistic studies. J.H. directed the project and wrote the manuscript with the contributions from L.-J.L. and M.-M.Z.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, LJ., Zhang, MM., Deng, Z. et al. NIR-II emissive anionic copper nanoclusters with intrinsic photoredox activity in single-electron transfer. Nat Commun 15, 4688 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49081-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49081-8

This article is cited by

-

Regulation of the photophysical dynamics of metal nanoclusters by manipulating single-point defects

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Lighting up metal nanoclusters by the H2O-dictated electron relaxation dynamics

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Photocatalytic dihydroxylation of light olefins to glycols by water

Nature Communications (2024)