Abstract

Shuttling of lithium polysulfides and slow redox kinetics seriously limit the rate and cycling performance of lithium-sulfur batteries. In this study, Fe3O4-dopped carbon cubosomes with a plumber’s nightmare structure (SP-Fe3O4-C) are prepared as sulfur hosts to construct cathodes with high rate capability and long cycling life for Li-S batteries. Their three-dimensional continuous mesochannels and carbon frameworks, along with the uniformly distributed Fe3O4 particles, enable smooth mass/electron transport, strong polysulfides capture capability, and fast catalytic conversion of the sulfur species. Impressively, the SP-Fe3O4-C cathode exhibits top-level comprehensive performance, with high specific capacity (1303.4 mAh g−1 at 0.2 C), high rate capability (691.8 mAh gFe3O41 at 5 C), and long cycling life (over 1200 cycles). This study demonstrates a unique structure for high-performance Li-S batteries and opens a distinctive avenue for developing multifunctional electrode materials for next-generation energy storage devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The multielectron conversions of sulfur atoms endow lithium-sulfur (Li-S) batteries with superior theoretical specific capacity (1675 mAh g−1)1,2,3. Moreover, sulfur is abundant, inexpensive, and environmentally friendly4,5. These distinguishing features make them promising for use in Li-S batteries for consumer electronic products6,7. However, several unsolved problems hinder the realization of their improved performance and practical application. First, sulfur and most of the lithium polysulfides (LiPSs) are insulators, which leads to slow redox kinetics and limited active sulfur utilization6,8. Second, shuttling of the lithium polysulfides (consisting of Li2S8, Li2S6, and Li2S4) and the slow kinetics for LiPSs conversion result in rapid capacity fading and a loss of coulombic efficiency4,9,10,11. Third, the large volume difference between S and Li2S causes shedding of the active materials from the current collector in the charge/discharge process12,13,14.

In this context, a number of strategies have been developed to address these obstacles15,16,17. Notably, the construction of multifunctional sulfur hosts is an efficient approach to improve the performance of Li-S batteries by taking advantage of their flexible structural/functional designability18,19,20. Among the multiple developed sulfur hosts, porous carbon particles (PCPs) are attractive candidates owing to their high conductivity, high porosity/specific surface areas (SSAs), and high structural stability3,21. However, the available PCP-based Li-S batteries still do not meet the ever-increasing demand. The main reasons for this difference include: (1) most PCPs only have micropores or obstructed pores, which makes it difficult for sulfur and electrolytes to penetrate deeply into their interior22,23,24; (2) hindered mass transport in the interiors of thick electrodes severely limits the contact between the LiPSs and the internal active matrix of PCPs, leading to poor sulfur utilization25,26; (3) the absence of polar active sites in PCPs leads to weak adsorption and slow catalytic conversion of the LiPSs. Therefore, the introduction of 3D continuous open channels and polar species (e.g., metal oxides) into PCPs is a desirable strategy for solving these problems. Recently, bicontinuous mesoporous structures have attracted much attention for use in energy storage applications27,28,29, because these structures provide 3D continuous frameworks and open mesochannels (Fig. 1a for illustration), which enable smooth mass transport into the deep internal areas of electrode materials and thus remarkably increase the accessibility of the inner active sites30,31. However, the construction of bicontinuous architectures is highly challenging due to their complex curved channels; for example, double or single primitive categories are called plumber’s nightmare structures32,33,34. The currently available techniques, such as photolithography, 3D printing and molecular self-assembly, are still difficult to produce these structures, especially at the mesoscale (2–50 nm)35,36,37,38,39. Therefore, bicontinuous mesoporous materials has rarely been used in energy storage applications40,41; their contributions to Li-S battery performance have remained unexplored, which inspires the interest of study.

a Schematic preparation of SP-Fe3O4-C with a plumber’s nightmare (bicontinuous) structure. b SEM image of an SP-Fe3O4-C cubosome along the (100) direction. c SEM image of a fractured SP-Fe3O4-C cubosome. The inset shows a high-magnification SEM image of a local area. d SAXS pattern of the SP-Fe3O4-C powder. e TEM image of an SP-Fe3O4-C cubosome and the size distribution curve for the Fe3O4 particles (inset). f HRTEM image of a Fe3O4 nanoparticle in SP-Fe3O4-C. The inset presents a high-magnification SEM image of a local area. g Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm and pore size distribution of SP-Fe3O4-C (inset).

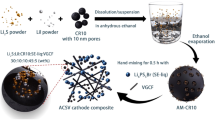

Here, we report the preparation of Fe3O4-dopped carbon cubosomes (named SP-Fe3O4-C) with a single-network plumber’s nightmare structure (i.e., single primitive (SP) bicontinuous topology). The synthetic strategy employed polymer cubosomes (PCs; cubosomes generally refer to colloidal particles with bicontinuous cubic liquid crystal phases) as the removable template and a biomass-derived Fe metal-phenolic network (Fe-MPN) as the Fe3O4 and carbon precursor (Fig. 1). The PCs were obtained by self-assembly of a block copolymer (BCP) in solution through precise adjustment of the self-assembly parameters. The Fe-MPN was utilized for three reasons: (1) its precursors, plant polyphenols, are natural and nontoxic biomasses42,43,44; (2) the Fe ions are uniformly coordinated in the network and can be directly (one-step) converted into Fe3O4 nanoparticles evenly doped in a carbon matrix after the pyrolysis of Fe-MPN, avoiding the complicated steps of traditional postloading methods for Fe3O4 particles45,46,47; and (3) the uniformly distributed Fe3O4 nanoparticles possess certain conductivity (5 × 104 S m−1) which is sufficient for charge transfer during battery operation and serve as active sites to capture the LiPSs and accelerate their catalytic conversions20,48,49. Based on these merits, the resultant SP-Fe3O4-C had a high Fe3O4 loading content of 19.5 wt% and a large SSA of 485 m2 g−1. The Li-S batteries with the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathodes (~ 75 wt% sulfur loading) exhibited a high initial discharge capacity of 1303.4 mAh g−1 at 0.2 C, impressive rate performance (691.8 mAh g−1 at 5C), and high cycling stability (capacity retention rate over 68.1% and a 0.027% decay for each cycle over 1200 cycles at 1 C) and a high areal capacity of 6.5 mAh cm−2 at a sulfur loading of 8.2 mg cm−2. This comprehensive performance ranks among the top-level for reported carbon-based cathodes for Li-S batteries. The contributions of the bicontinuous structure and the Fe3O4 particles, along with the related mechanisms, were unveiled, which will help in the design and preparation of multifunctional cathode materials for Li-S batteries.

Results and discussion

Structural characterizations of SP-Fe3O4-C and SP-Fe3O4-C/S

The synthetic route toward SP-Fe3O4-C is illustrated in Fig. 1a. First, polymer cubosomes with an ordered double primitive topology (DP-PCs) were prepared via self-assembly of polystyrene-block-poly(ethylene oxide) (PS241-b-PEO45) in solution following previously reported procedures (see details in the Supplementary Information, SI)50. The resultant PCs had a unit cell parameter (a) of a = 92 nm (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). The DP-PCs were subsequently used as templates to prepare the carbon cubosomes by employing (-)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and Fe3+ as functional precursors. Typically, in a mixed aqueous solution with a pH of 6.8–7.2, Fe3+ ions and EGCG molecules diffused into the open channels of the DP-PCs and formed MPN@DP-PC composite particles after coordination. The resultant MPN@DP-PCs were collected via centrifugation (the details are given in the SI). As shown in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b), the mesochannels within the DP-PCs were fully filled with MPNs. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum demonstrated that the stretching vibration peak for the carbonyl group (C=O) in EGCG shifted from 1691 cm−1 to 1640 cm−1 in MPN@DP-PCs, indicating the presence of strong hydrogen bonds between the EGCG ligands and the PC templates (Supplementary Fig. 4c)51. Moreover, broadening of the HO-C stretching vibrational peaks of EGCG (3349 cm−1 and 3471 cm−1) indicated that the phenolic hydroxyl groups formed coordination bonds with the metal ions (Supplementary Fig. 4c)51.

The SP-Fe3O4-C particles were obtained by pyrolysis of the resultant MPN@DP-PCs at 350 °C and 800 °C for 2 h, respectively; in this process, the DP-PC templates were also removed. The molar ratio of EGCG to Fe3+ (nEGCG/nFe3+) impacted the final morphology of the obtained carbon particles (see Supplementary Fig. 5 and details in the SI). Thereafter, SP-Fe3O4-C was synthesized with the optimized molar ratio of nEGCG/nFe3+ = 1.3. TEM images revealed that the SP-Fe3O4-C particles had porous spherical structures with a mean size of 2.3 ± 0.4 μm (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 6). The cross-sectional SEM image of SP-Fe3O4-C confirmed the ordered mesoporous structure with a square lattice (Fig. 1c), while the high-magnification local SEM image clearly showed an SP cubic structure (inset of Fig. 1c). The mean side length of the SP-Fe3O4-C cubic unit (LC = 72 nm) was shorter than that of the PCs (Lt = 90 nm) owing to shrinkage of the SP skeleton during carbonization. The average frame and pore sizes of SP-Fe3O4-C were 33.2 ± 3.1 nm and 30.5 ± 3.8 nm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7). Moreover, the topology of SP-Fe3O4-C was also studied by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). As shown in Fig. 1d, the appearance of five characteristic peaks confirmed the SP structure of SP-Fe3O4-C (with a Pm\(\bar{3}\)m symmetry)27. The unit cell parameter of SP-Fe3O4-C was a = 70 nm, which was close to the length of the cubic units (LC = 72 nm) measured from the SEM image (Fig. 1c). The TEM images revealed that SP-Fe3O4-C had an internal interconnected porous structure with clear frameworks and mesopores (Fig. 1e). Apparently, numerous nanoparticles were homogeneously embedded in the carbon skeleton of SP-Fe3O4-C, and the average particle diameter was approximately 22 nm (inset of Fig. 1e). The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) micrograph showed clear lattice fringes for the (220) plane in Fe3O4 (d-spacing of 0.290 nm; Fig. 1f)52,53. The formation of Fe3O4 in the SP-Fe3O4-C was also confirmed by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern, in which all of the diffraction peaks were indexed to the Fe3O4 phase (JCPDS No. 88-0866, Supplementary Fig. 8a)54. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption analysis of SP-Fe3O4-C yielded a type IV isotherm with an H1-type hysteresis loop, validating the existence of mesopores (Fig. 1g)55,56, while the uptake at low pressures in the isotherm suggested the coexistence of micropores57. The average mesopore size was ~ 30 nm, which was consistent with the SEM results. Moreover, the micropores within the SP-Fe3O4-C sample had an average diameter of 0.3 nm. Additionally, the broad pore size distribution of 8–100 nm was probably caused by random stacking of the SP-Fe3O4-C particles58. The total and micropore volumes of the SP-Fe3O4-C composite were 1.08 cm3 g−1 and 0.11 cm3 g−1, respectively. The SSA of SP-Fe3O4-C was 485 m2 g−1. The porosity and surface area information of the SP-Fe3O4-C composite are presented in Supplementary Table. 1.

The Raman spectrum of SP-Fe3O4-C displayed two peaks attributed to the G (1589 cm−1) and D (1345 cm−1) bands (Supplementary Fig. 8b)59. A high G/D band intensity ratio (IG/ID~ 1.2) indicated a high degree of graphitization of the carbon framework, which favors electrical conductivity60. The Fe3O4 content of SP-Fe3O4-C was 19.5 wt% (Supplementary Fig. 8c) according to thermogravimetric analysis (TGA); this was confirmed with inductively coupled plasma‒mass spectrometry (ICP‒MS), which revealed an iron content of 13.8 wt% (i.e., a Fe3O4 content of 19.1 wt%). Moreover, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) demonstrated the presence of Fe, C, and O (Supplementary Fig. 9). The high-resolution Fe 2p spectrum was resolved into four main peaks at 726.8, 724.3, 713.8 and 711.3 eV, confirming the generation of Fe3O4 particles49.

The 3D continuous pore channels, highly graphitized carbon framework, and homogeneously distributed Fe3O4 nanoparticles make SP-Fe3O4-C a promising candidate sulfur host material. SP-Fe3O4-C-based cathodes were prepared by the sulfur melt-diffusion method, which yielded SP-Fe3O4-C/S composites (details in the Methods section). The channels of SP-Fe3O4-C were almost completely filled with sulfur according to the TEM images of SP-Fe3O4-C (Supplementary Fig. 10a, c) and SP-Fe3O4-C/S (Supplementary Fig. 10b, d), which demonstrated the successful sulfur loading of SP-Fe3O4-C. The homogeneous distribution of sulfur was shown with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental maps (Supplementary Fig. 10e). According to the TGA measurements, the sulfur content in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode was approximately 75 wt% (Supplementary Fig. 10f). In addition, the XRD pattern of SP-Fe3O4-C/S confirmed the successful loading of long sulfur chains with an orthorhombic structure (S8, JCPDS no. 77-0145, Supplementary Fig. 10g)61. Moreover, the SSA and pore volume of SP-Fe3O4-C/S sharply decreased to 49 m2 g−1 and 0.31 cm3 g−1, respectively, indicating the encapsulation of sulfur (Supplementary Fig. 10h, i; Supplementary Table. 1). It should be noted that the adsorption/desorption isotherm and the pore size distribution also demonstrated the presence of a little spare pore space inside SP-Fe3O4-C/S, which could provide additional tunnels for mass diffusion (Supplementary Fig. 10h, i).

As a control sample, Fe3O4 nanoparticle doped carbon particles with discontinuous mesopores were also prepared and labelled B-Fe3O4-C (Supplementary Fig. 11a). As revealed by SEM, the B-Fe3O4-C particles were irregular (Supplementary Fig. 11b). A high-magnification TEM image demonstrated the presence of discontinuous pores and embedded Fe3O4 nanoparticles in B-Fe3O4-C (Supplementary Fig. 11c). The XRD (Supplementary Fig. 8a), Raman (Supplementary Fig. 8b) and XPS (Supplementary Fig. 12) spectra of B-Fe3O4-C were similar to those of SP-Fe3O4-C. The ferric oxide content of B-Fe3O4-C was 21.0 wt% based on TGA (Supplementary Fig. 8c), which was close to that of SP-Fe3O4-C. The SSA of B-Fe3O4-C was 418 m2 g−1 (Supplementary Fig. 13a), which was slightly smaller than that of SP-Fe3O4-C, probably due to discontinuous pores leading to impalpable internal surfaces. The micropores within the B-Fe3O4-C sample had an average diameter of 0.8 nm. The total and micropore volumes of the B-Fe3O4-C composite were 0.64 cm3 g−1 and 0.10 cm3 g−1, respectively. The control sample was also loaded with sulfur via the melt-diffusion method, producing B-Fe3O4-C/S. The sulfur content of B-Fe3O4-C/S was 74 wt% (Supplementary Fig. 13b), close to that of SP-Fe3O4-C/S (75 wt%). The SSA of B-Fe3O4-C/S was much lower (1 m2 g−1), confirming the successful loading of sulfur (Supplementary Fig. 13c, d), and other specific parameters of B-Fe3O4-C/S were listed in Supplementary Table. 1.

Performance of Li-S batteries with the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode

The electrochemical properties of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode were tested systematically with assembled CR2032 Li-S cells. To verify the structural advantages of SP-Fe3O4-C/S for Li-S batteries, the electrochemical properties of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S and B-Fe3O4-C/S cathodes were compared (Fig. 2). At a low current of 0.2 C, the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode exhibited a higher initial discharge capacity of 1303.4 m Ah g−1 than the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode (1196.4 mAh g−1). Moreover, the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode exhibited stable cycling performance with a lower capacity decay of only 0.024% per cycle after 120 cycles (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode underwent a very fast capacity decay, with 57% of the capacity retained after 120 cycles, which corresponded to a much greater capacity decay of 0.35% per cycle (Fig. 2a). The corresponding galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD) curves from the 1st to 120th cycles (Supplementary Fig. 14) showed that, compared with those of the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode, the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode exhibited two well-defined longer discharge plateaus even after 120 cycles62. This result demonstrated the enhanced sulfur redox kinetics, especially for the two redox processes by which solid S8 was converted to highly soluble Li2S8 and soluble Li2S4 was converted to insoluble Li2S2/Li2S in the whole sulfur redox process63. During cycling of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode, the SP-Fe3O4-C/S particles were uniformly dispersed in the cathode matrix (Supplementary Fig. 15a). After cycling, there was almost no sulfur aggregation on the surface of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode (Supplementary Fig. 15b). Moreover, the bicontinuous structure was retained after repeated charge/discharge cycles (Supplementary Fig. 15c, d), indicating the good structural stability of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S composite. In contrast, the significant morphological changes in the cycled B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode revealed its poor stability (Supplementary Fig. 16).

a Cycling performance at 0.2 C. b Rate performance. c GCD curves of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S-based Li-S batteries from the 1st to 1200th cycles at 1 C. d Long cycling performance at 1 C. e Cycling performance of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S-based Li-S batteries with sulfur loadings of 3.2, 5.6 and 8.2 mg cm−2. f Performance radar chart of the SP-Fe3O4-C and PCP cathode-based Li-S batteries with reported state-of-the-art examples.

The rate performance was evaluated and is presented in Fig. 2b. The SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode demonstrated superior rate performance, with capacities of 1303.4, 1197.0, 1093.9, 911.0, 837.4 and 788.8 mAh g−1 at 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 and 4.0 C, respectively; even at a high rate of 5 C, it still delivered a high capacity of 691.8 mAh g−1 (Fig. 2b). The rate capacity of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S solution was much greater than that of the B-Fe3O4-C/S solution at all testing rates. Impressively, the capacity of SP-Fe3O4-C/S was restored to 1273.8 mAh g−1 after the current was returned to 0.2 C. The high rate performance of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode indicated fast electron transport along the carbon framework and enhanced ion transport in the 3D mesopores during battery operation. The battery with the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode also exhibited high cycling capacity at 1 C (Fig. 2c, d). The SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode had an initial capacity of 965.8 mAh g−1 with an average coulombic efficiency of 99.94% over 1200 cycles. Notably, the SP-Fe3O4-C/S-based batteries exhibited a low capacity decay of 0.027% per cycle after 1200 cycles, outperforming the performance of the B-Fe3O4-C/S-based batteries. Because a high sulfur loading is required for practical application64,65, a thick cathode with a high areal loading of sulfur was tested as well. At 0.1 C, stable cycling was seen with sulfur loads of 3.2, 5.6, and 8.2 mg cm−2 (Fig. 2e). After 60 cycles, the Li-S battery with the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode had a high areal capacity of 6.5 mAh cm−2 with an 8.2 mg cm−2 areal loading of sulfur, which was much greater than those of commercial Li-ion batteries (~ 4 mAh cm−2). Among those of all PCP-based22,23,24,66,67,68 (Supplementary Table. 2 and Fig. 2f) and even carbon-based sulfur hosts (Supplementary Table. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 17) reported in the past five years, the comprehensive performance of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S-based Li-S battery ranked near the top.

Exploring the effect of Fe3O4 on the performance of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S-based Li-S battery

The high electrochemical performance of SP-Fe3O4-C/S stemmed from a synergistic effect of the unique 3D interconnected open channels and the carbon frameworks with embedded Fe3O4 particles. The key roles of Fe3O4 included chemical adsorption and catalytic conversion of the LiPSs62. As a control sample, PCPs were prepared with an SP structure but without Fe3O4 particles (SP-C) (Supplementary Fig. 18). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to understand the chemical interaction between Fe3O4 and LiPSs. Figure 3a displays the optimized configurations of LiPSs on the polar Fe3O4 (220) plane, in which Li+ interacted with the O atoms and Sn2− was bound to the Fe atoms on the Fe3O4 surface (220)49. The calculated binding energies for Li2S2, Li2S4, Li2S6, and Li2S8 on the Fe3O4 surface were −5.31, −4.26, −4.39 and −4.93 eV, respectively (Fig. 3a), which were much greater than those on graphene. These results were confirmed by the differential charge densities of Fe3O4 and LiPSs, in which the charge density of the Fe atom increased while that of the S atom decreased, and these results supported a chemical adsorption interaction between Fe3O4 and the LiPSs (Fig. 3a). The strong adsorption of the LiPSs may greatly alleviate migration during charging/discharging. Visualized adsorption experiments were carried out to evaluate the capacity of LiPSs adsorption on SP-Fe3O4-C. Typically, 10 mg of equivalent carbon black, SP-C, B-Fe3O4-C, or SP-Fe3O4-C was added to a Li2S6 solution (4 mM, 5 mL), after which the mixture was stirred. After 24 h, the mixture with SP-Fe3O4-C became nearly transparent after incubation (the inset of Fig. 3b). In sharp contrast, the samples containing the carbon black, SP-C and B-Fe3O4-C still exhibited dark yellow colors. Moreover, the UV‒vis absorption spectra of the supernatants were determined (Fig. 3b), and adsorption of the polysulfides decreased in the order: blank samples > carbon black >SP-C > B-Fe3O4-C > SP-Fe3O4-C. Notably, the polysulfide signal from the SP-Fe3O4-C sample was almost undetectable, indicating that the polysulfide adsorption capacity was greater than that of the control sample.

a DFT-calculated energies for adsorption of different LiPSs on Fe3O4 (220). Lithium, sulfur, iron, and oxygen atoms are marked with green, yellow, brown and red, respectively. The yellow and blue regions represent increases and decreases in charge density, respectively. The adsorption energies are given under each structure. b UV‒vis spectra of Li2S6 adsorbed by different samples. The insets show photographs of Li2S6 adsorption by different samples: blank, carbon black, SP-C, B-Fe3O4-C and SP-Fe3O4-C. c High-resolution Fe 2p XPS spectrum of the cycled SP-Fe3O4-C/S composite. d High-resolution S2p XPS spectrum of the cycled SP-Fe3O4-C/S composite. e–g Li2S precipitation experiments of SP-Fe3O4-C, B-Fe3O4-C and SP-C. h Schematic illustration of the adsorption and catalytic conversion of sulfur species.

To study the mechanism for LiPSs conversion catalyzed by SP-Fe3O4-C, the XPS spectra of the cycled SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode were recorded, as shown in Fig. 3c, d. The peaks corresponding to Fe, C, O, S, and Li are shown in Supplementary Fig. 19. In the high-resolution Fe 2p spectrum (Fig. 3c), the peaks corresponding to the Fe3+ 2p3/2, Fe2+ 2p1/2, Fe3+ 2p3/2, and Fe2+ 2p3/2 states were located at 726.2 eV, 724.2 eV, 713.1 eV, and 711.1 eV, respectively. All of the Fe 2p peaks moved to lower binding energies than those of SP-Fe3O4-C/S before cycling. These negative shifts suggested chemical interactions between the Fe-O species and Sx2-, which led to an increase in the electron densities of the Fe species49,69. The high conductivity of Fe3O4 facilitated charge transfer, which enhanced catalytic conversion of the LiPSs. In addition, a new Fe-S signal at 707.9 eV was observed (Fig. 3c), indicating that the strong interaction between Fe3O4 and LiPSs led to the generation of FeSx species70. In the resolution S 2p spectrum (Fig. 3Fd), the peaks at 165.4 eV and 164.3 eV were ascribed to the S 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 states, respectively71. The peaks at 170.0 eV and 168.7 eV were assigned to thiosulfate72. Notably, a new peak appeared at 162.8 eV, which confirmed the formation of Fe-S bonds70. This result was consistent with the Fe 2p spectrum. The XPS results demonstrated chemical bonding between Fe3O4 and LiPSs, and the formation of Fe-S bonds led to a reduced energy barrier for LiPSs conversion70,73.

Generally, uncontrolled deposition of ion- and electron-insulating Li2S on a cathode surface hinders continuous LiPSs conversion and significantly slows the kinetics of LiPSs conversion74,75,76,77. Therefore, to demonstrate the fast catalytic conversion of LiPSs induced by the SP-Fe3O4-C, a Li2S precipitation experiment was performed. The highest area capacity (245 mAh gs−1) and earliest current response (2.75 × 103 s) were observed for SP-Fe3O4-C (Fig. 3e). In comparison, the area capacities of B-Fe3O4-C and SP-C were 125 mAh gs−1 and 75 mAh gs−1, respectively (Fig. 3f, g). The current responses of B-Fe3O4-C and SP-C were 5.22 × 103 s and 13.39 × 103 s, respectively, which were much slower than that of SP-Fe3O4-C. Therefore, SP-Fe3O4-C showed the largest Li2S deposition capacity and fastest nucleation/growth of Li2S. These results reflected three facts: (1) compared with SP-C, SP-Fe3O4-C enabled faster catalytic conversion kinetics between the LiPSs and Li2S due to the presence of Fe3O4; (2) the fastest current response of SP-Fe3O4-C indicated the rapid growth of Li2S; and (3) the highest Li2S deposition capacity of SP-Fe3O4-C suggested the conversion of more LiPSs to Li2S. The entire process of LiPSs capture and catalytic conversion of the SP-Fe3O4-C cathode is illustrated in Fig. 3h.

Study on the effect of the bicontinuous structure on the performance of Li-S batteries

The advantages of the bicontinuous structure for mass/electron transfer of SP-Fe3O4-C/S are illustrated in Fig. 4a. First, the enhanced reaction kinetics were revealed by cyclic voltammetry (CV) of SP-Fe3O4-C/S, and the voltammograms were recorded over a voltage window of 1.7 to 2.8 V. In the contour maps for the CV curves (0.1–0.5 mV s−1; Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 20), the CV curves displayed two redox peaks: peak A at ~ 2.0 V corresponded to the reduction of S8 to Li2Sx (X = 4, 6, 8), and peak B at ~ 2.3 V was ascribed to the subsequent transition to Li2S2/Li2S78. Another oxidation peak (anode peak C at ~ 2.4 V) was assigned to the oxidation of Li2S2/Li2S to S878. Importantly, compared with the B-Fe3O4-C/S-based battery, the SP-Fe3O4/C/S-based battery showed higher currents, lower polarization voltages and narrower half-peak widths (0.17 V) at each scanning rate, indicating faster redox reactions kinetics of LiPSs conversion. Second, the mass transfer kinetics in the 3D continuous mesochannels were quantitated with the Li+ diffusion coefficient (DLi+). The DLi+ was calculated via the Randles−Sevcik equation79,80,81:

where Ip is the peak current, \(n\) is the number of electrons in the reaction (n = 2), A is the electrode area (A = 1.2 cm2), v is the scanning rate (V/s), and CLi+ is the Li-ion concentration in the electrolyte (CLi+ = 1 × 10−3 mol ml−1)18. Based on the linear relationship between Ip and v1/2 for the main redox peaks (A, B and C in the CV curve), the DLi+ values for SP-Fe3O4-C/S were determined to be 1.83 × 10−8, 8.12 × 10−9 and 4.74 × 10−8 cm2 s−1, respectively (Fig. 4d, e). In contrast, the DLi+ values of B-Fe3O4-C/S were 5.39 × 10−9, 5.10 × 10−9 and 4.18 × 10−8 cm2 s−1, respectively. The SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode had a higher DLi+ at each redox peak, indicating that electrolyte diffusion in SP-Fe3O4-C/S was better than that in B-Fe3O4-C/S (Supplementary Table. 4), which benefited from the 3D continuous mesochannels and contributed to the improved redox kinetics. Third, we used time-of-flight secondary-ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) to reveal the depth profiles of S− secondary ions in the cycled cathodes (0.2 C after 50 cycles) (Fig. 4f, g). With respect to the cycled B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode, the intensity of S− decreased with increasing etching depth, indicating nonuniform distribution of the S− on the outer surface of the cycled cathode. In contrast, the S− intensity in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode was almost constant with increasing etching depth, and there was no obvious aggregation of S− on the cathode surface, indicating inhibition of LiPSs migration and a uniform distribution of S− in the whole SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode, as illustrated in Fig. 4h. Fourth, the charge transfer capability of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode was evaluated with in situ electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) during the 1st charge/discharge cycle (Fig. 4i). The results showed that the charge transfer resistance (Rct) of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode was significantly lower than that of the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode. Upon recharging, no significant changes in the charge transfer resistance were observed, suggesting stable solid–liquid–solid conversion kinetics78. Notably, the Rct of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode was always lower than that of the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode during the entire discharge/charge process, verifying that fast electron transfer occurred in the 3D continuous carbon framework of SP-Fe3O4-C/S (Fig. 4i).

a Schematic showing ion/electron transport in the continuous mesochannels of SP-Fe3O4-C/S; carbon frame, Fe3O4 nanoparticle, sulfur, electron, and lithium ion are marked with grain, red, yellow, pink, and green, respectively. b Contour maps for the CV curves of SP-Fe3O4-C/S (0.1 ~ 0.5 mV s−1). c Contour maps for the CV curves of B-Fe3O4-C/S (0.1~0.5 mV s−1). d, e Peak currents versus square root of scan rates of SP-Fe3O4-C/S (A1, B1, C1) and B-Fe3O4-C/S (A2, B2, C2). f Normalized depth profiles for the S- secondary ion fragments obtained by TOF-SIMS analyses of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S and B-Fe3O4-C/S cathodes after 50 cycles at 0.2 C. g 3D depth profiles of the B-Fe3O4-C/S (g1) and SP-Fe3O4-C/S (g2) cathodes. h Schematic for LiPSs capture and Li2S deposition in SP-Fe3O4-C/S; carbon frame, Fe3O4, sulfur atom, and lithium atom are marked with grain, red, yellow, and green, respectively. i In situ EIS: voltage curve of the in situ EIS during the 1st cycle (i1); in situ EIS data for the SP-Fe3O4-C/S (i2) and B-Fe3O4-C/S (i3) cathodes during the 1st cycle; the corresponding Rct histograms of SP-Fe3O4-C/S and B-Fe3O4-C/S obtained from the in situ EIS at different states (i4).

After evaluating the role of the bicontinuous structure, the LiPSs conversion mechanism was also studied. In situ Raman spectroscopy was used to monitor the redox reaction, in which a small circular hole was created on the side of the cathode, which exposed the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode to the incident laser beam (Supplementary Fig. 21). At the open circuit voltage (OCV), three predominant peaks appeared at 153.5, 219.4, and 472.9 cm−1 and were attributed to solid S8, and they gradually decreased after discharging to 2.26 V. Afterward, the signals for the S62− and S42− + S52− species appeared at 406.7 and 461.1 cm−1, respectively, and became more intense as the discharge time increased. Then, the intensities of all peaks gradually became weaker until the end of discharge. Upon charging to 2.24 V, the signals for the sulfur-containing species reappeared. After charging to 2.8 V, the polysulfide signals had almost disappeared, and S8 was regenerated. During the whole charge/discharge process, signals attributed to the discharge product Li2S were not found owing to interference from the solvent and poor crystallinity82. The opposite reaction processes were detected during discharging/charging, demonstrating good reversibility for the conversion of LiPSs in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode.

Finally, the finite element method based on COMSOL Multiphysics software was used for simulations of the bicontinuous structure in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode. A model with continuous framework and channel was constructed and then the channels were filled with sulfur to simulate the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode. In contrast, another model with discontinuous mesopores was also constructed and then filled with sulfur to simulate the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode. The Li+ diffusion model within the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode is presented in Fig. 5a. The simulation results (Fig. 5b) showed that the interpenetrating mesopores increased the reaction interfacial area for the sulfur redox reactions and enabled a more homogeneous local current distribution, leading to improved reaction kinetics for the whole cathode. In comparison, due to the difficulty of ion transport, the conversion of polysulfides in areas distant from the separator within the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode occurred at slower rates and exhibited uneven current distributions, leading to low sulfur utilization throughout the entire cathode. This contrast was particularly evident in thick electrodes with high sulfur loadings, as supported by the finite element method simulations (Fig. 5c). As shown in Fig. 5c, the sulfur in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode was almost fully utilized throughout the whole electrode during the discharge process. Moreover, the quantitative distributions of S8 and Li2S in the cathode after discharge are given in Fig. 5d. There was faster S8 conversion in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode during the discharge process than in the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode (Fig. 5d1, 2). Moreover, the Li2S generation ratio was higher than that in the B-Fe3O4-C/S cathode after full discharge, and Li2S was uniformly deposited throughout the entire SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode (Fig. 5d3, 4). This may have led to a higher sulfur utilization efficiency in accordance with the discharge curves with higher capacities and lower polarization voltages for SP-Fe3O4-C/S relative to B-Fe3O4-C/S (Supplementary Fig. 22). Another factor to be considered is the mechanical stability of the cathode during the discharge process, as there can be an 80% volume expansion in converting S8 to Li2S. A large volume expansion may lead to severe mechanical stress generated by mutual compression among active particles. The simulation results (Fig. 5e) showed that inhomogeneous sulfur utilization resulted in a nonuniform distribution of the mechanical stress in B-Fe3O4-C/S. In contrast, evenly distributed Li2S deposition in SP-Fe3O4-C/S led to a homogeneous volume expansion and a smaller stress gradient distributed across the entire electrode. Simultaneously, the bicontinuous structure accommodated the deposition of Li2S, which reduced the volume expansion and enabled obviously weakened extrusion of sulfur particles, as shown in Fig. 5e, which mitigated the stress concentration. A homogeneous stress distribution may have prevented damage and collapse of the electrode materials due to mechanical failure, which would be highly beneficial for long-term cycling with high sulfur loadings. In a word, the finite element simulations confirmed that SP-Fe3O4-C/S had rapid ion transport capability, fast S8 reduction kinetics, and structural advantages in tolerating large volume changes.

a Schematic illustration of the SP-Fe3O4-C/S-based Li-S battery and Li+ diffusion in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S cathode; carbon frame, Fe3O4 nanoparticles, sulfur, and lithium ion are marked with grain, red, yellow, and green color, respectively. b–e Finite element analysis of the electrochemical and mechanical performance: b Local current density distributions for the Li2S-generated reaction in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S and B-Fe3O4-C/S models; c Simulation of the cathode utilization evolution in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S and B-Fe3O4-C/S models from 50% depth of charge (DOD) to 100% DOD, where cathode utilization was defined as the ratio of the actually generated Li2S to the theoretically generated Li2S; d S8 retention ratio evolution from 0 to 20% DOD: SP-Fe3O4-C/S (d1) and B-Fe3O4-C/S (d2); Li2S generation ratio evolution from 0 to 20% DOD: SP-Fe3O4-C/S (d3) and B-Fe3O4-C/S (d4); e Simulated electrode expansion stress after S8 was converted into Li2S in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S and B-Fe3O4-C/S models.

In summary, Fe3O4-dopped carbon cubosomes with a single primitive bicontinuous structure were constructed from EGCG and Fe3+ precursors with the help of a BCP-based cubosome template. The obtained SP-Fe3O4-C exhibited 3D ordered interpenetrating mesochannels and a 3D continuous carbon skeleton, high sulfur loading and facilitated electron/mass transport within the cathode. Moreover, the uniformly distributed Fe3O4 on the continuous carbon skeleton adsorbed the LiPSs and catalyzed their conversion. Impressively, the SP-Fe3O4-C-based cathode in the Li-S battery provided a high reversible capacity of 1303.4 mAh g−1 at 0.2 C, a high rate capability of 691.8 mAh g−1 at 5 C and an impressive cycling life over 1200 cycles at 1 C with a low decay rate of 0.027% per cycle. In addition, computational simulations demonstrated that the unique bicontinuous channels and frameworks achieved high sulfur utilization, uniform Li2S deposition and fast Li+/e− transportation with SP-Fe3O4-C. This work provides a promising example of a carbon-based sulfur host with a unique structure for use in high-performance Li-S batteries. We also believe that the preparation strategy and mechanism presented here will contribute to future construction of multifunctional cathode materials for high-performance energy storage devices.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Poly(ehylene glycol) methyl ether (Mn = 2000 g mol−1), copper(\({{{{{\rm{{I}}}}}}}\)) bromide (CuBr), styrene (St), 2-bromoisobutyryl, triethylamine (Et3M), N,N,N′,N′,N″-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA), tetrahydrofuran (THF), alcohol, 1,4-dioxane, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), (-)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O), potassium hydroxide (KOH), 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPs), 1,3-dioxolane (DOL), dimethoxyethane (DME), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP) were purchased from Adamas Reagent (shanghai) and Energy Chemical. Deionized water was used in all steps. St was distilled before using. Other agents were used without purification.

The synthesis of PS-b-PEO45

The PS-b-PEO45 block copolymer was synthesized by atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) method83. Firstly, PEO-Br macroinitiator was synthesized as follows: (1) PEO2000 (20 g) was dissolved in freshly distilled dichloromethane (DCM, 100 mL) in a Schlenk-flask under stirring (500 rpm). After the addition of Et3N (3.5 mL), the mixture was cooled to 0 °C and kept stirring for 1 h. (2) Then, 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide (7.7 mL) was added dropwise under stirring. The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h in an ice-water bath. (3) The solution after the reaction was recrystallized by isopropanol for several times until the solid turned white. (4) Then, the white solid was fully dissolved by DCM (20 mL) and the almost colorless solution was obtained. Subsequently, the solution was added dropwise into 500 mL cold ether under stirring to precipitate the product. The generated white precipitate was filtered and washed with cold ether for three times. (5) The obtained snow-white product (PEO-Br) was dried under vacuum at room temperature overnight. Second, the PS-b-PEO45 block copolymer was synthesized through the following steps: (1) 1 g prepared PEO45-Br, 50 mg CuBr and 80 μL PMDETA were added into a Schlenk flask. Afterwards, a calculated amount of styrene (9 mL for PS241-b-PEO45 and 5 mL for PS180-b-PEO45) was transferred to the flask. (2) The mixture in the flask was mixed by ultrasonic and further deoxygenated by three freeze-pump-thaw cycles. (3) The flask was subsequently immersed in an oil bath at 120 °C and reacted for 6 h. (4) Then, the product was dissolved in DCM (50 mL) and then passed through a short column of basic alumina to remove copper complexes. (5) The mixture solution was concentrated and then dropped into a large amount of methanol (500 mL) under stirring to precipitate the white precipitate. (6) The final product (PS-b-PEO45) was filtered and dried under vacuum at room temperature for 24 h.

Preparation of the PC template

DP-PCs were prepared by a cosolvent method50. Typically, 20 mg PS241-b-PEO45 was dissolved in 2 mL mixture solution of dioxane/dimethylformamide (92:8, v/v). The solution was stirred for 4 h at room temperature for complete dissolution of the copolymer. Then 2 mL water was added at a controlled rate (1 mL h−1) to the polymer solution under stirring (200 rpm). The mixtures were dialyzed against water to remove organic solvent and freeze the morphology. Then, DP-PCs were obtained by centrifugation at 955 × g for 3 min.

Preparation of SP-Fe3O4-C

Aqueous solution of EGCG (30 mM, 1 mL) and FeCl3·6H2O (30 mM, 1.3 mL) solution were sequentially added to the DP-PC aqueous solution (1 mg mL−1, 20 mL). The suspension was vigorously stirred at 500 rpm for 2 h to ensure the complete diffusion of the EGCG and Fe3+ into the pore channels of DP-PC templates. The pH of the suspension was then raised by adding 25 mL of 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPs) buffer (100 mM) solution (pH = 6.8–7.2). The reaction was continuously stirred for another 20 min. The product was collected and purified by centrifugation at 955 × g for 3 min and washed with ethanol and deionized water for at least three cycles. Finally, the collected product was dried at 80 °C for 12 h to yield MPN@DP-PC composite. Pyrolysis of the MPN@DP-PC was carried out in a tubular furnace under nitrogen atmosphere at 350 °C for 2 h and 800 °C for 2 h, respectively, with a heating rate of 2 °C min−1.

Control experiments on the effect of the mole ratio of EGCG and Fe3+ on the formation of SP-Fe3O4-C

The preparation conditions were similar to those described in section ‘Preparation of SP-Fe3O4-C’ except that the molar ratios of EGCG and Fe3+ were varied. In these control experiments, the molar ratio (it was also equal to the volume ratio since the precursor concentration was the same, [EGCG] = [Fe3+] = 30 mM) of EGCG and Fe3+ was adjusted to 1:0.5, 1:0.9, 1:1, 1:1.3, 1:1.7, and 1:2.1, respectively.

Preparation of B-Fe3O4-C

Firstly, PS180-b-PEO45 was prepared by ATRP as described in section ‘The synthesis of PS-b-PEO45’. Afterwards, 20 mg PS180-b-PEO45 was dissolved in 4 mL THF to prepare the polymer solution, and quickly pour the mixed solution of 4 mL ethanol and 8 mL water into the polymer solution under vigorous stirring to prepare the spherical micelle solution. Then, 0.45 mmol EGCG and 0.59 mmol Fe3+ were added sequentially to the above micelle solution. After stirring for another 2 h, an equal volume of pH buffer (prepared as described in section Preparation of SP-Fe3O4-C) was added. The mixture solutions were stirred for 20 min before purification. The desired B-Fe3O4-C was obtained through a pyrolyzing process (post-treated details are given in section Preparation of SP-Fe3O4-C).

Preparation of SP-Fe3O4-C/S and B-Fe3O4-C/S

Impregnation of sulfur was carried out by a melt-diffusion method84. Briefly, SP-Fe3O4-C and sulfur were well-mixed as a mass ratio of 1:3. Then the mixture was transferred into a quartz tube furnace and heated at 155 °C for 12 h, resulting in the SP-Fe3O4-C/S sample. B-Fe3O4-C/S was prepared by the same method under similar conditions.

Adsorption test of lithium polysulfides85

The Li2S6 solution was prepared by dissolving sulfur and Li2S (5:1, molar ration) in a DOL/DME (1:1, v/v) solution at 60 °C for 24 h. All samples (SP-Fe3O4-C, B-Fe3O4-C, and carbon black) were dried at 80 °C under vacuum oven for 12 h before the absorption test. Then, 10 mg samples were added into the Li2S6 solution (4 mM, 5 mL) and kept for 24 h in an argon-filled glove box. The supernatants were taken for the UV-vis absorption spectroscopy analysis.

Li2S precipitation experiments86

The Li2S8 solution was prepared by uniformly mixing Li2S and S at a mole ratio of 1:7 in the electrolyte, which consisted of 1 M LiTFSI salt (DOL/DME 1:1, v/v) with 1 wt% LiNO3. The batteries for the Li2S precipitation experiments were assembled by using lithium foil as the counter electrode, SP-Fe3O4-C coated on carbon cloth as the working electrode and 20 μL Li2S8 solution was dropping onto the working electrode. The cells were galvanostatically discharged to 2.06 V at 0.112 mA, then maintained at 2.05 V until the current was less than 0.01 mA. The procedures for the Li2S precipitation experiments on B-Fe3O4-C and SP-C were similar except the use of different carbon samples.

Electrochemical measurements

The electrodes for the Li-S cells were prepared by mixing the active material (SP-Fe3O4-C/S or B-Fe3O4-C/S), carbon black and PVDF in the mass ratio of 7:2:1 in NMP. The mixture was coated on an aluminium (Al) foil collector, followed by drying at 60 °C in a vacuum oven for 12 h. The mass of active materials in the cathode was measured by the mass difference between the assembled cathode and the pure Al foil collector. The Li-S cells were assembled with lithium metal foil as the anode, polypropylene (PP) membrane served as the separator, and 50 μL electrolyte in each cell. The entire process of battery assembly was carried out in an Ar-filled glove box. The electrochemical performance was tested on a LAND Battery Tester with a voltage window of 1.7 to 2.8 V. Cyclic voltammetry and in situ impedance testing were performed on a bio-logical electrochemical workstation with the voltage range from 1.7 to 2.8 V. Each electrochemical datum was the average value based on the measurements of three cell samples. All the electrochemical tests were carried out in a constant temperature laboratory (25 °C). All the specific capacities of the cells have been normalized based on the weight of sulfur.

Characterizations

Liquid-phase nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR):1H NMR analyses were performed on a Bruker 400 (400 MHz for proton) spectrometer at room temperature with 16 scans. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC): Gel permeation chromatograph was performed at on a EcoSEC-HLC-8321GPC/HT from Tosoh, Japan. The test temperature was 40 oC, the standard sample was monodispersed styrene, and the mobile phase was tetrahydrofuran. The sample was prepared by dissolving 2 mg of polymer sample in HPLC tetrahydrofuran, filtered through a filter and injected into a GPC test vial. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM): Scanning electron microscopy was performed on a JSM-7800F super-resolution field emission scanning electron microscope from Japan Electronics Corporation, with an accelerating voltage of 5.0 kV and a resolution of 1.2 nm. A drop of the sample dispersion was added to a clean silicon wafer during sample preparation and allowed to evaporate for 24 h. The wafer was washed in advance with deionized water, acetone, and anhydrous ethanol, then immersed in ethanol and removed from the ethanol solution before use, and allowed to dry naturally. The sample can be added only after natural drying. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM): Transmission electron microscopy was performed using a Tecnai G2 spirit Biotwin biological transmission electron microscope (FEI, USA), with an accelerating voltage of 120 kV and a point resolution of 0.49 nm. The samples were prepared by placing a drop of sample dispersion on a copper grid and evaporating for 24 h. Magnetic samples were prepared by double networking. Sections were prepared by embedding the samples with resin and then slicing them with an EM/UC7 ultra-thin sectioning machine from Leica, Germany. The samples were sliced using a UC7 ultrathin slicer with a thickness of 100 nm. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurement: Nitrogen adsorption isotherms were measured at 77 K on an Autosorb-iQA3200-4 sorption analyzer (Quantatech, USA). The samples were degassed under vacuum at 393 K for 8 h before testing. The Brunauer−Emmett−Teller (BET) method was used to calculate the specific surface area. The desorption branch of the isotherm and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method was used to calculate the pore size distribution and pore volume. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy: FTIR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet 6700 infrared spectrometer from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). The sample was dried under vacuum at 80 oC for 8 h. A small amount of samples powder was taken and fully ground with dried KBr powder, and then pressed into thin slices. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS): XPS was characterized using an AXIS Ultra DLD-type X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with the monochromatic Kα radiation of the Al target as the X-ray source (1486.6 eV) and the binding energy of the C 1 s peak (284.6 eV). X-ray diffraction (XRD): XRD patterns were recorded on a D8 DaVinci X-ray diffractometer (Bruker, Germany) with a test angle range of 5–80° (2θ) and a rate of 6°/min. Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS): Small angle X-ray scattering was performed at the BL10U1 small-angle X-ray scattering station (third generation synchrotron light source) with an X-ray wavelength (λ) of 2 Å and a tube length of 27.6 m using the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Source (SSRF). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA): Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is carried out on a TA SDT Q650 (USA). To acquire the Fe content. The samples were heated to 800 oC under air atmosphere with a heating rate of 10 oC/min. While to obtain the sulfur contents, the sulfur encapsulated samples were heated to 400 oC under high-purity nitrogen with a heating rate of 10 oC/min. Raman Spectroscopy: Raman spectroscopy was conducted on an In Via Qontor confocal micro-Raman spectrometer (Renishaw, UK) to characterize the graphitic degree of carbon materials. In situ Raman: In situ Raman spectra was obtained using a self-made cell, the schematic diagram of the in situ cell device is shown in Supplementary Fig. 21. Raman measurements were acquired using a Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution at 532 nm. Ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (UV-vis): UV-vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600, Shimadzu, Japan) was used for the UV test of LiPSs adsorption experiment. Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS): TOF-SIMS characterization was carried out on the ION TOF SIMS 5–100 instrument. For the TOF-SIMS 3D analysis, a 3 k eV Cs+ beam with a current of 30 nA was used on the electrode. The imaged area was 40 μm × 40 μm. The cathodes were galvanostatic cycled within the voltage window of 1.7 to 2.8 V at 0.2 C for 50 cycles before the TOF-SIMS characterization. The samples for TOF-SIMS measurements were prepared and sealed in bags in a glove box filled with argon. After transferring the samples encapsulated in valve bags filled with argon, the TOF-SIMS measurements were conducted under vacuum.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the main text and Supplementary Information. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, all of them available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Shi, Z., Ding, Y., Zhang, Q. & Sun, J. Electrocatalyst modulation toward bidirectional sulfur redox in Li–S batteries: From strategic probing to mechanistic understanding. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2201056 (2022).

Fang, R. et al. More reliable lithium-sulfur batteries: status, solutions and prospects. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606823 (2017).

Dong, C. et al. Boosting Bi-directional redox of sulfur with dual metal single atom pairs in carbon spheres toward high-rate and long-cycling lithium–sulfur battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301505 (2023).

Hua, W. et al. Selective catalysis remedies polysulfide shuttling in lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 33, 2101006 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Heterostructure ZnSe-CoSe2 embedded with yolk-shell conductive dodecahedral as two-in-one hosts for cathode and anode protection of lithium–sulfur full batteries. Energy Stor. Mater. 47, 223–234 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Advances in lithium–sulfur batteries: From academic research to commercial viability. Adv. Mater. 33, 2003666 (2021).

Luo, C. et al. A chemically stabilized sulfur cathode for lean electrolyte lithium sulfur batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 14712–14720 (2020).

Huang, Z. et al. Anion chemistry in energy storage devices. Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 616–631 (2023).

Shi, Z., Li, M., Sun, J. & Chen, Z. Defect engineering for expediting Li–S chemistry: Strategies, mechanisms, and perspectives. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100332 (2021).

Feng, L. et al. Regulating polysulfide diffusion and deposition via rational design of core–shell active materials in Li–S batteries. ACS Nano 16, 7982–7992 (2022).

Shen, Z. et al. Cation-doped ZnS catalysts for polysulfide conversion in lithium–sulfur batteries. Nat. Catal. 5, 555–563 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. A perspective toward practical lithium–sulfur batteries. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1095–1104 (2020).

Luo, C. et al. Atomic-layer-deposition functionalized carbonized mesoporous wood fiber for high sulfur loading lithium sulfur batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 14801–14807 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. A conductive molecular framework derived Li2S/N,P-codoped carbon cathode for advanced lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1602876 (2017).

Fan, Z. et al. Solid/solid interfacial architecturing of solid polymer electrolyte–based all-solid-state lithium–sulfur batteries by atomic layer deposition. Small 15, 1903952 (2019).

Kim, S. et al. Polymer interface-dependent morphological transition toward two-dimensional porous inorganic nanocoins as an ultrathin multifunctional layer for stable lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 15644–15652 (2021).

Ma, L. et al. Wide-temperature operation of lithium–sulfur batteries enabled by multi-branched vanadium nitride electrocatalyst. ACS Nano 17, 11527–11536 (2023).

Gao, R. et al. Unraveling the coupling effect between cathode and anode toward practical lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2303610 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Engineering the conductive network of metal oxide-based sulfur cathode toward efficient and longevous lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2002076 (2020).

He, J., Luo, L., Chen, Y. & Manthiram, A. Yolk–shelled C@Fe3O4 nanoboxes as efficient sulfur hosts for high-performance lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702707 (2017).

Sun, Z. et al. Catalytic polysulfide conversion and physiochemical confinement for lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1904010 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Hierarchical defective Fe3-xC@C hollow microsphere enables fast and long-lasting lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2001165 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Tantalum-based electrocatalyst for polysulfide catalysis and retention for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Matter 3, 920–934 (2020).

Su, L. et al. Cobalt-embedded hierarchically-porous hollow carbon microspheres as multifunctional confined reactors for high-loading Li-S batteries. Nano Energy 85, 105981 (2021).

Lei, J. et al. Exploring and understanding the roles of Li2Sn and the strategies to beyond present Li-S batteries. Chem 6, 2533–2557 (2020).

Wang, N. et al. Thickness-independent scalable high-performance Li-S batteries with high areal sulfur loading via electron-enriched carbon framework. Nat. Commun. 12, 4519 (2021).

Xiang, L. et al. Ultrahigh-rate Na/Cl2 batteries through improved electron and ion transport by heteroatom-doped bicontinuous-structured carbon. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 62, e202312001 (2023).

Xiang, L. et al. Porous polymer cubosomes with ordered single primitive bicontinuous architecture and their sodium–iodine batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15497–15508 (2022).

Han, L. & Che, S. An overview of materials with triply periodic minimal surfaces and related geometry: From biological structures to self-assembled systems. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705708 (2018).

Xiang, L. et al. Block copolymer self-assembly directed synthesis of porous materials with ordered bicontinuous structures and their potential applications. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207684 (2023).

Ghanbari, R., Assenza, S. & Mezzenga, R. The interplay of channel geometry and molecular features determines diffusion in lipidic cubic phases. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 094901 (2019).

Lee, H. et al. Thermodynamically stable plumber’s nightmare structures in block copolymers. Science 383, 70–76 (2024).

Finnefrock, A. C. et al. The plumber’s nightmare1: a new morphology in block copolymer−ceramic nanocomposites and mesoporous aluminosilicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 13084–13093 (2003).

Poppe, S. et al. Liquid organic frameworks: The single-network “plumber’s nightmare” bicontinuous cubic liquid crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3296–3300 (2020).

Zekoll, S. et al. Hybrid electrolytes with 3D bicontinuous ordered ceramic and polymer microchannels for all-solid-state batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 185–201 (2018).

Al-Ketan, O. & Abu Al-Rub, R. K. Multifunctional mechanical metamaterials based on triply periodic minimal surface lattices. Adv. Eng. Mater. 21, 1900524 (2019).

Stefik, M. et al. Networked and chiral nanocomposites from ABC triblock terpolymer coassembly with transition metal oxide nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 1078–1087 (2012).

Thomas, E. L. Nanoscale 3D ordered polymer networks. Sci. China Chem. 61, 25–32 (2018).

Cui, S. et al. Core–shell gyroid in ABC bottlebrush block terpolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21719–21727 (2022).

Choudhury, S. et al. Nanoporous cathodes for high-energy Li–S batteries from gyroid block copolymer templates. ACS Nano 9, 6147–6157 (2015).

Werner, J. G., Rodríguez-Calero, G. G., Abruña, H. D. & Wiesner, U. Block copolymer derived 3-D interpenetrating multifunctional gyroidal nanohybrids for electrical energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1261–1270 (2018).

Ejima, H. et al. One-step assembly of coordination complexes for versatile film and particle engineering. Science 341, 154–157 (2013).

Ejima, H., Richardson, J. J. & Caruso, F. Metal-phenolic networks as a versatile platform to engineer nanomaterials and biointerfaces. Nano Today 12, 136–148 (2017).

Rahim, M. A. et al. Phenolic building blocks for the assembly of functional materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1904–1927 (2019).

Shin, M. C. et al. Atomic-distributed coordination state of metal-phenolic compounds enabled low temperature graphitization for high-performance multioriented graphite anode. Small 16, 2003104 (2020).

Feng, Y.-Y., Chen, Y.-Q., Wang, Z. & Wei, J. Synthesis of mesoporous carbon materials from renewable plant polyphenols for environmental and energy applications. New Carbon Mater. 37, 196–222 (2022).

Xiao, Z. et al. General and precise carbon confinement of functional nanostructures derived from assembled metal–phenolic networks for enhanced lithium storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 18605–18614 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Iron (Fe, Ni, Co)-based transition metal compounds for lithium-sulfur batteries: Mechanism, progress and prospects. J. Energy Chem. 73, 513–532 (2022).

Xin, S. et al. Coupling of oxygen vacancies and heterostructure on Fe3O4 via an anion doping strategy to boost catalytic activity for lithium-sulfur batteries. Small 19, 2207924 (2023).

Lin, Z. et al. Tunable self-assembly of diblock copolymers into colloidal particles with triply periodic minimal surfaces. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 56, 7135–7140 (2017).

Lin, Z. et al. Ordered mesoporous metal–phenolic network particles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 335–341 (2020).

Zeng, Z. et al. Nanostructured Fe3O4@C as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 248, 15–21 (2014).

Lei, D. et al. Iron oxide nanoconfined in carbon nanopores as high capacity anode for rechargeable alkaline batteries. Nano Energy 48, 170–179 (2018).

Liu, G. et al. MOF derived in-situ carbon-encapsulated Fe3O4@C to mediate polysulfides redox for ultrastable lithium-sulfur batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 381, 122652 (2020).

Tian, H. et al. Quantitative control of pore size of mesoporous carbon nanospheres through the self-assembly of diblock copolymer micelles in solution. Small 12, 3155–3163 (2016).

Peng, L. et al. Versatile nanoemulsion assembly approach to synthesize functional mesoporous carbon nanospheres with tunable pore sizes and architectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 7073–7080 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Metal organic framework cubosomes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 62, e202215985 (2023).

Peng, L. et al. Spiral self-assembly of lamellar micelles into multi-shelled hollow nanospheres with unique chiral architecture. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7403 (2021).

Lu, X. F., Yu, L. & Lou, X. W. Highly crystalline Ni-doped FeP/carbon hollow nanorods as all-pH efficient and durable hydrogen evolving electrocatalysts. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav6009 (2019).

Herold, F. et al. Nanoscale hybrid amorphous/graphitic carbon as key towards next-generation carbon-based oxidative dehydrogenation catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 5898–5906 (2021).

Zhao, C. et al. A high-energy and long-cycling lithium–sulfur pouch cell via a macroporous catalytic cathode with double-end binding sites. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 166–173 (2021).

Song, Y. et al. Rationalizing electrocatalysis of Li–S chemistry by mediator design: progress and prospects. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1901075 (2020).

Bruce, P. G., Freunberger, S. A., Hardwick, L. J. & Tarascon, J.-M. Li–O2 and Li–S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 11, 19–29 (2012).

Yang, X. et al. Structural design of lithium–sulfur batteries: from fundamental research to practical application. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 1, 239–293 (2018).

Peng, H.-J., Huang, J.-Q., Cheng, X.-B. & Zhang, Q. Review on high-loading and high-energy lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700260 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. N/O dual-doped hollow carbon microspheres constructed by holey nanosheet shells as large-grain cathode host for high loading Li-S batteries. Energy Stor. Mater. 24, 644–654 (2020).

Jin, Z. et al. Ordered micro-mesoporous carbon spheres embedded with well-dispersed ultrafine Fe3C nanocrystals as cathode material for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 388, 124315 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. 3D pomegranate-like structures of porous carbon microspheres self-assembled by hollow thin-walled highly-graphitized nanoballs as sulfur immobilizers for Li–S batteries. Nano Energy 63, 103894 (2019).

Su, Z. et al. Expediting polysulfide catalytic conversion for lithium–sulfur batteries via in situ implanted ultrafine Fe3O4 nanocrystals in carbon nanospheres. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 24117–24127 (2020).

Qiao, Z. et al. Anchoring polysulfides and accelerating redox reaction enabled by Fe-based compounds in lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100970 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Three-dimensional embroidered ball-like α-Fe2O3 synthesised by a microwave hydrothermal method as a sulfur immobilizer for high-performance Li–S batteries. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 7066–7075 (2022).

Cao, Z. et al. Integrating polar and conductive Fe2O3–Fe3C interface with rapid polysulfide diffusion and conversion for high-performance lithium–sulfur batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 11, 39772–39781 (2019).

Chen, H. et al. Catalytic materials for lithium-sulfur batteries: mechanisms, design strategies and future perspective. Mater. Today 52, 364–388 (2022).

Yuan, H. et al. Conductive and catalytic triple-phase interfaces enabling uniform nucleation in high-rate lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1802768 (2019).

Yang, T. et al. Uniform growth of Li2S promoted by an organophosphorus-based mediator for high rate Li-S batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 381, 122685 (2020).

Pan, H. et al. Non-encapsulation approach for high-performance Li–S batteries through controlled nucleation and growth. Nat. Energy 2, 813–820 (2017).

Zeng, F.-L. et al. Improve the electrodeposition of sulfur and lithium sulfide in lithium-sulfur batteries with a comb-like ion-conductive organo-polysulfide polymer binder. Energy Stor. Mater. 18, 190–198 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Regulating the spin state configuration in bimetallic phosphorus trisulfides for promoting sulfur redox kinetics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22516–22526 (2023).

Ye, Z. et al. A high-efficiency CoSe electrocatalyst with hierarchical porous polyhedron nanoarchitecture for accelerating polysulfides conversion in Li–S batteries. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002168 (2020).

Lei, T. et al. Inhibiting polysulfide shuttling with a graphene composite separator for highly robust lithium-sulfur batteries. Joule 2, 2091–2104 (2018).

Tsao, Y. et al. A nickel-decorated carbon flower/sulfur cathode for lean-electrolyte lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2101449 (2021).

Xia, J. et al. TinO2n–1/Mxene hierarchical bifunctional catalyst anchored on graphene aerogel toward flexible and high-energy Li–S batteries. ACS Nano 16, 19133–19144 (2022).

Yu, S., Azzam, T., Rouiller, I. & Eisenberg, A. Breathing” vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10557–10566 (2009).

Weng, W. et al. Molten salt electrochemical modulation of iron–carbon–nitrogen for lithium–sulfur batteries. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 60, 24905–24909 (2021).

Guo, B. et al. Controlled synthesis of porous carbon nanostructures with tunable closed mesopores via a silica-assisted coassembly strategy. CCS Chem. 3, 1410–1422 (2020).

Cai, J. et al. 3D printing of a V8C7–VO2 bifunctional scaffold as an effective polysulfide immobilizer and lithium stabilizer for Li–S batteries. Adv. Mater. 32, 2005967 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (22225501 and 52073173, Y.M.; 52203268, F.X.; 52072205, G.Z.), Open Fund of Shanghai Jiao Tong University-Shaoxing Institute of New Energy and molecular Engineering (JDSX2022025, Y.M.), Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (23XD1431700, C.Z.), Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Specialized Polymer Materials for Aerospace (18DZ2253500, C.Z.), the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20174, C.Z.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFA0705703, G.Z.), the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20174, G.Z.), Guangdong Innovative and Entrepreneurial Research Team Program (2021ZT09L197, G.Z.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KQTD20210811090112002, G.Z.), and the Overseas Research Cooperation Fund of Tsinghua Shenzhen International Graduate School (the fund was provided by the school platform and no specific fund number, G.Z). They also appreciate Dr. Feng Tian and the time-resolved USAXS Beamline BL10U1 at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for SAXS measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L., F.X., G.Z., and Y.M. conceived and designed the project. H.Z. performed most experiments and interpreted the data. H.L. conducted the electrochemical measurements and analyzed the data. R.L. performed the related synthesis of MPN. M.Z. contributed to the finite element simulation. Y.J. contributed to the DFT calculation. L.X. helped with the electrochemical data analysis. C.Z. and T.H. contributed to helpful discussions. X.W. and Z.P. helped to revise and polish the article. H.Z., H.L., F.X. G.Z. and Y.M. co-wrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhang, M., Liu, R. et al. Fe3O4-doped mesoporous carbon cathode with a plumber’s nightmare structure for high-performance Li-S batteries. Nat Commun 15, 5451 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49826-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49826-5

This article is cited by

-

Magnetic graphitic biochar from spent mushroom substrate for efficient removal of trace cobalt from aqueous solutions

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2026)

-

High-dimensional strain unlocks fast polysulfide redox kinetics for lithium-sulfur batteries

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Thermocouple-integrated resonant microcantilever for on-chip thermogravimetric (TG) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) dual characterization applications

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2025)

-

Hyaluronic acid molecular orientation induces uniform distribution of polysulfides for high-performance lithium-sulfur battery

Communications Materials (2025)

-

Heteroatoms Synergistic Anchoring Vacancies in Phosphorus-Doped CoSe2 Enable Ultrahigh Activity and Stability in Li–S Batteries

Nano-Micro Letters (2025)