Abstract

Porous frameworks constructed via noncovalent interactions show wide potential in molecular separation and gas adsorption. However, it remains a major challenge to prepare these materials from low-symmetry molecular building blocks. Herein, we report a facile strategy to fabricate noncovalent porous crystals through modular self-assembly of a low-symmetry helicene racemate. The P and M enantiomers in the racemate first stack into right- and left-handed triangular prisms, respectively, and subsequently the two types of prisms alternatively stack together into a hexagonal network with one-dimensional channels with a diameter of 14.5 Å. Remarkably, the framework reveals high stability upon heating to 275 °C, majorly due to the abundant π-interactions between the complementarily engaged helicene building blocks. Such porous framework can be readily prepared by fast rotary evaporation, and is easy to recycle and repeatedly reform. The refined porous structure and enriched π-conjugation also favor the selective adsorption of a series of small molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

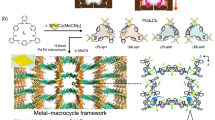

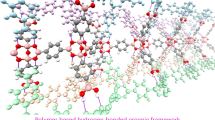

Porous frameworks have acquired impressive development over the past few decades and have been intensively applied in a rich variety of fields1,2,3,4. Conventionally, porous frameworks are constructed by covalent and coordination interactions, giving rise to covalent organic frameworks (COFs)5,6,7 and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)8,9,10, respectively. Recently, noncovalent interactions including hydrogen bonds11,12,13,14,15 and π-interactions16,17,18,19,20 have also been utilized to fabricate porous frameworks. Due to the considerable solubility of discrete building blocks, such noncovalent porous frameworks reveal impressing solubility, processability and recyclability18,21. Regarding the noncovalent porous frameworks constructed majorly by π-interactions, the building blocks generally adopt a high-symmetry structure, typically as C2, C3, S4, etc., with relatively regular and extended ends, which subsequently stacked together to form the knot of the framework (Fig. 1)22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. So far, advances in the fabrication of porous frameworks sustained by π-interactions are substantially limited21,30. Besides, it remains a remarkable challenge to fabricate noncovalent porous frameworks with anomalous molecules in low symmetry.

Noncovalent porous frameworks formed by various organic molecules including tris-o-phenylenedioxycyclotriphosphazene (TTP), tris(3,5-dipyridylphenyl)mesitylene (Py6Mes), benzene-1,3,5-triyltris(9H-carbazol-9-yl)methanone (PhTCz), 3,3′,4,4′-tetra(trimethylsilylethynyl)biphenyl (TMSBP), 2,8-di(10H-phenothiazin-10-yl)dibenzofuran (PBO), tetra(9-anthracyl-p-phenyl)methane (TAPM), 4,7-di(10-phenyl-10H-phenothiazin-3-yl)[1,2,5]thiadiazolo[3,4-c]pyridine (DPBT), N-(4-(9H-carbazol-9-yl)phenyl)phthalimide (PAICz). The abbreviations are adopted from the literatures22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

Helicenes are a type of non-planar aromatic molecules with distinctive helical π-conjugated skeletons31,32, of which the twisted structures contribute to various interesting self-assembly entities33,34,35,36. The stereochemical structures and widely distributed π-conjugation of helicenes benefit to the uncompact packing and the introduction of porosity21. Herein, we used a helicene derivative diphenyltriphenylenyl[6]helicene (D6H)37 with low symmetry to fabricate noncovalent porous frameworks merely sustained by π-interactions through modular self-assembly. Racemic D6H was employed and the P and M enantiomers were self-sorted upon the primary self-assembly into oppositely twisted triangular prisms, and such high-symmetry secondary building blocks with 31 screw axes subsequently hexagonally stacked into a porous framework with one-dimensional (1D) channels. Crystal analysis along with calculations showed that the P and M enantiomers were associated together solely through multiple π-interactions, and thus the porous frameworks were highly stable at high temperatures, but readily recyclable/reformable through simple solvent treatment. The refined open pore structure and the pure aromatic C–H composition also favor the selective adsorption and direct analysis of various small molecules.

Results and discussion

Single crystals of D6H with regular shapes were prepared by slow diffusion of a vapor of n-pentane into the solution of racemic D6H in dichloromethane (CH2Cl2). X-ray diffraction analysis indicated that the crystals possess a trigonal lattice in an R\(\bar{3}\) space group (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, the crystal lattice showed a hollow hexagonal structure along the c-axis with solvent molecules randomly distributed in the channels (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2). The hexagonally arranged 1D channels revealed a relatively large diameter of 14.5 Å (Fig. 2a). PLATON calculation38 showed that such porous crystal has a fairly high potential volume of 32.9% for solvent encapsulation.

a Space-filling representation of the crystal. Carbon atoms of M- and P-D6H are marked in blue and red, respectively. CH2Cl2 and n-pentane molecules possibly existing in a disordered form were removed by solvent mask using Olex2. b Analysis on the modular self-assembly of racemic D6H into a hexagonal porous framework with 1D channels.

By further scrutinizing the crystal structure, it was found that the D6H molecules assembled in a hierarchical manner (Fig. 2b). First, the P enantiomers were self-sorted and stacked into right-handed twisted triangular prisms, while the M enantiomers gave left-handed prisms. In the twisted triangular prisms with 31 screw axes, each helical pitch was composed of three molecules with the helicene moiety pointing inward. Despite of the irregular shape of D6H, the neighboring D6H molecules engaged with each other through multiple intermolecular C–H···π interactions with length in a range of 2.70–2.90 Å (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Subsequently, the right- and left-handed twisted triangular prisms alternatively stacked together in a hexagonal fashion and the arch-like packing of each six prisms generated a 1D channel. Notably, the oppositely handed triangular prisms were locked with each other also through C–H···π interactions (bond lengths of 2.95 Å and 2.76 Å, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Overall, the discrimination of chirality allowed the formation of homochiral prismatic secondary building blocks and the further generation of a heterochiral hexagonal porous framework. Interestingly, the self-assembly of the enantiopure D6H molecules occurred in a lamellar manner and yielded solid crystals (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5), again indicating the important role of chirality discrimination in the formation of the porous crystals.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) were employed to study the thermodynamic properties of the porous crystals. Upon increasing the temperature from 30 to 180 °C, a series of endothermic signals were found in the DSC curve (Fig. 3a), which could be attributed to the release of solvent molecules from the crystals. With the temperature elevated to 285 °C, a sharp endothermic peak was recorded (Fig. 3a), which may correspond to the melting of the crystals. The elimination of solvent was also reflected by the TGA curve which revealed a total weight loss of 21.8% before 285 °C (Supplementary Fig. 6). In detail, the TGA curve showed two periods of weight loss, sequentially corresponding to the detaching of surface-adsorbed solvents at lower temperatures and the escaping of encapsulated solvents upon the melting of the porous crystals. Optical microscopy observation further confirmed the melting point around 285 °C (Supplementary Fig. 7). Notably, during the heating process, the crystals kept the prismatic shape below the melting point. Variable-temperature powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) showed that the peaks such as the ones corresponding to (220), (250), (18\(\bar{1}\)) and (75\(\bar{1}\)) faces remained constant when the temperature was increased from room temperature to 275 °C (Fig. 3b), indicating a high thermal stability of the porous crystals.

a DSC curves of the crystals of racemic D6H obtained by solvent diffusion (scan rate = 10 °C/min). b Variable-temperature PXRD (Co Kα radiation, λ = 1.79021 Å) patterns of the crystals of racemic D6H obtained by solvent diffusion. c Space-filling representation of the crystals of racemic D6H obtained after melting and PXRD (Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.54178 Å) patterns of the two types of crystals of racemic D6H. d Crystal diagrams and NCI maps showing the intermolecular interactions (denoted by arrows) between D6H molecules in a crystal of racemic D6H obtained by solvent diffusion.

Interestingly, by slowly cooling the molten D6H from 300 to 250 °C, a new crystalline phase was formed (Fig. 3c). Single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis showed that the new crystals possess a monoclinic lattice with a P21/n space group (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 8). The P and M enantiomers solely stacked into a compact nonporous lamellar structure (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 9), without any detectable residual solvents (Supplementary Fig. 10). The transition of the crystal phase was also reflected by the DSC curves (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 11). Notably, the transformation from the porous crystals to the solid crystals was thermodynamically irreversible. However, these solid crystals can be easily dissolved in CH2Cl2 or chloroform (CHCl3) and the recycled D6H molecules are ready to reform the porous crystals.

Theoretical calculations were further conducted to gain more insights into the molecular association in the D6H porous crystals. Noncovalent interaction (NCI) analysis39,40,41,42 revealed the presence of abundant π-interactions [−0.015 <Sign(λ2)ρ < 0.010, in green color] between the neighboring homochiral D6H molecules in a single prism (Fig. 3d). The extension of triangular prisms is also accomplished by π-interactions [−0.015 <Sign(λ2)ρ < 0.010, in green color] between the D6H molecules lining up along c-axis (Supplementary Fig. 40). On the other hand, the π-interactions [−0.020 <Sign(λ2)ρ < 0.005, in green color] distributed between the neighboring heterochiral D6H molecules assist the bundling of heterochiral triangular prisms and sustain the hexagonal porous framework (Fig. 3d). It appeared that the remarkable thermal stability of the D6H porous crystals originates from the abundant π-interactions29.

Due to the lability of noncovalent interactions, noncovalent porous frameworks were normally constructed via relatively stationary crystallization approaches21,30. However, we found that D6H can spontaneously self-assemble into porous materials through fast solvent evaporation from various solvents including CH2Cl2, CHCl3 and toluene (Fig. 4a). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images showed that the resulting powder was comprise of micron-sized crystals with hexagonal prism morphologies similar to the single crystals of racemic D6H obtained by slow solvent diffusion (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Figs. 12–15). PXRD confirmed that these small crystals duplicated the highly ordered structure of the single crystals (Fig. 4c). Such swift and facilely controlled crystallization of racemic D6H was probably favored by the less anisotropic molecular shape which is easier to adapt a crystal lattice via fast orientation, as well as the hierarchical self-assembly manner.

a Schematic illustration showing the preparation of single crystals of racemic D6H via slow solvent diffusion and the facile preparation of powder of small crystals of racemic D6H via fast rotary evaporation. b, c Corresponding SEM images and PXRD (Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.54178 Å) patterns. d TGA curves of the powder of racemic D6H dried from CH2Cl2 before and after activation (scan rate = 10 °C/min) and SEM image of the activated powder.

The simple dissolution-evaporation process also allowed the quick and large-scale preparation of powder of small porous crystals. The powder of racemic D6H can be readily desolvated and activated by heating at 150 °C under vacuum (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17) without any prominent interference to the crystal morphology and structure (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19). The treated powder of racemic D6H can quickly take up and release iodine in an ethanol solution, indicating the activation of porosity (Supplementary Fig. 20).

The activated powder of racemic D6H was further subjected for gas adsorption. While the activated powder of racemic D6H failed to take up an adequate amount of N2 or CO2, it revealed a significant adsorption capacity of tetrahydrofuran (THF). The adsorption of THF vapor at 283 K revealed a pore volume (Vp) of 0.453 cm3/g (Fig. 5a), which was close to the theoretical value (0.532 cm3/g, simulated by ZEO++43,44,45).

a Adsorption isotherms of N2, CO2 and THF vapor. b Schematic illustration of an adsorption experiment where the activated powder of racemic D6H is exposed to various solvent vapors for 3 days. c TGA curves of the activated powder of racemic D6H before and after the adsorption of various solvents (scan rate = 10 °C/min). The adsorption capacities are listed in the inserted table. d Crystal diagrams of THF@D6H and NCI map for the intermolecular interactions between THF and D6H molecules. e Adsorption of THF by the activated powder of racemic D6H upon multiple adsorption-desorption cycles. Insets are the corresponding SEM images of the powder sampled from the adsorption-desorption cycles. f 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) spectra of the activated powder of racemic D6H after adsorption of DOX, CYH and a blend vapor of DOX with CYH.

Subsequently, we investigated the adsorption of a series of common volatile organic solvents. The activated powder of racemic D6H was exposed to the vapors of a variety of solvents for 2 days to evaluate the practical gas adsorption capacity (Fig. 5b). TGA curves of the D6H powder collected after the adsorption of THF, diisopropyl ether (DIPE), methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), dioxane (DOX), CHCl3, carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), 1,2-dichloroethane (C2H4Cl2) and toluene revealed correspondent weight loss of 7.18%, 9.30%, 6.02%, 4.68%, 10.87%, 10.52%, 7.51% and 4.58% respectively before 285 °C, corresponding to an adsorption amount of 1.075, 1.004, 0.693, 0.566, 0.990, 0.750, 0.821 and 0.523 mmol/g under their saturated vapor pressure, respectively (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 21, Supplementary Table 4). The adsorption of THF, DIPE, MTBE, DOX, C2H4Cl2 were also characterized by 1H NMR (Supplementary Figs. 22–26), and the adsorption capacity was calculated to be 1.004, 0.990, 0.622, 0.552, 0.693 mmol/g, respectively (Supplementary Table 5). On the contrary, the activated powder of racemic D6H showed negligible adsorption capacity towards methanol (MeOH, 0.151 mmol/g) and cyclohexane (CYH, 0.146 mmol/g) (Fig. 5c). Obviously, the adsorption feature of the activated powder of racemic D6H was sensitive to the polarity of small molecules46,47. Additionally, when soaked in the MeOH solution of biphenyl, azobenzene and diphenyl disulfide respectively, the activated powder of racemic D6H revealed a relatively high adsorption capacity towards these aromatic derivatives (Supplementary Figs. 27–29), which demonstrated the sufficient size of the 1D channels to accommodate larger aromatic contents. Notably, the activated powder of racemic D6H can be repeatedly and constantly used to capture and release the small molecules, without any prominent loss of morphological and structural integrity in 10 cycles (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31, Supplementary Table 6).

To gain more details of the association of the porous framework with the adsorbed molecules, crystals of racemic D6H containing THF and CHCl3 (THF@D6H and CHCl3@D6H, respectively) were obtained by slow diffusion of a n-pentane vapor into the solution of racemic D6H in THF or CHCl3. X-ray diffraction analysis showed that the crystals of THF@D6H and CHCl3@D6H were also in an R\(\bar{3}\) space group (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11, Supplementary Figs. 34 and 36). The adsorbed THF and CHCl3 molecules were all located at the concave sites of the channels (Supplementary Figs. 35 and 37). In each cross section of the channel, six molecules were found to be uniformly embedded in the gap of two D6H molecules (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 38). In the crystal of THF@D6H, a THF molecule associates with a D6H molecule through multiple C–H···π interactions (bond lengths ranged from 3.00 to 3.40 Å) and simultaneously interacts with the neighboring D6H molecule via a C–H···O hydrogen bond (bond length of 2.89 Å) (Fig. 5d). Such host-guest interactions were further confirmed by NCI analysis [−0.016 <Sign(λ2)ρ < 0.006, in green color] (Fig. 5d). Similarly, C–H···π interactions (bond length of 2.24 Å) and relative weak C–H···Cl hydrogen bonds (bond lengths of 3.06 Å and 3.11 Å, respectively) were found in the crystals of CHCl3@D6H (Supplementary Fig. 39), which was also demonstrated by NCI analysis [−0.018 <Sign(λ2)ρ < 0.005, in green color] (Supplementary Fig. 44).

The activated powder of racemic D6H was eventually applied for molecular separation. Mixtures of two target solvents in equal volume were used to generate the blend vapors for adsorption. Regarding THF and its analogues 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (MTHF), the activated powder of racemic D6H revealed considerably higher adsorption of THF (0.622 mmol/g) than MTHF (0.354 mmol/g) (Supplementary Fig. 32, Supplementary Table 7). For the blend of DIPE and n-hexane (NH), the porous powder showed an appealing adsorption selectivity of ca. 5: 1 (DIPE 0.891 mmol/g vs NH 0.184 mmol/g) (Supplementary Fig. 33, Supplementary Table 8). Notably, in spite of the greater partial pressure of CYH48,49, the adsorption of DOX was approximately 29 times higher (DOX 0.410 mmol/g vs CYH 0.014 mmol/g) (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Table 9), indicating a remarkable discrimination between cyclic ethers and alkanes.

In summary, we have reported a distinctive type of noncovalent porous framework constructed by modular self-assembly of a low-symmetry racemic helicene derivative. The discrimination of chirality allowed the formation of homochiral triangular prism secondary building blocks and the arch-like packing of the prisms further led to the formation of a heterochiral hexagonal porous framework. The abundant π-interactions between the complementarily engaged helicene molecules favored the emergence of high thermal stability, recoverability and adsorption selectivity. Overall, this work demonstrates a facile approach to organize anomalous molecules into stable noncovalent porous crystals through hierarchical and modular self-assembly. It also broadens the utilization of π-interactions in the fabrication of noncovalent porous frameworks. The rich presence of non-planar aromatic molecules, e.g. other helicene derivatives and curved nanographenes, would pave a dynamic way for the creation of porous materials.

Methods

Preparation of single crystals of racemic D6H

Single crystals of racemic D6H were grown in CH2Cl2 with the diffusion of a vapor of n-pentane. Typically, 5.0 mg of racemic D6H was dissolved in 1 mL of CH2Cl2, and a vapor of n-pentane was allowed to diffuse into the solution for 3 days. The resulting crystals were washed with n-pentane and then dried.

Preparation of powder of small crystals of racemic D6H

50.0 mg of racemic D6H was dissolved in 20 mL of CH2Cl2, CHCl3 or toluene, respectively, and then the solvents were removed rapidly via rotary evaporation. The resulting powder was directly subjected for analysis.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the authors upon request. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2224852 (D6H crystallized by solvent diffusion), 2268959 (M-D6H), 2224863 (D6H crystallized after melting), 2255046 (CHCl3@D6H) and 2259036 (THF@D6H). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. A Source Data file of the coordinates of computational optimized structures is provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, Q. et al. Docking in metal-organic frameworks. Science 325, 855–859 (2009).

Liu, X., Xu, Y. & Jiang, D. Conjugated microporous polymers as molecular sensing devices: microporous architecture enables rapid response and enhances sensitivity in fluorescence-on and fluorescence-off sensing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8738–8741 (2012).

Slater, A. G. & Cooper, A. I. Function-led design of new porous materials. Science 348, 988 (2015).

Pei, X., Bürgi, H.-B., Kapustin, E. A., Liu, Y. & Yaghi, O. M. Coordinative alignment in the pores of MOFs for the structural determination of N-, S-, and P-containing organic compounds including complex chiral molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 18862–18869 (2019).

Côté, A. P. et al. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 310, 1166–1170 (2005).

El-Kaderi, H. M. et al. Designed synthesis of 3D covalent organic frameworks. Science 316, 268–272 (2007).

Jiang, J., Zhao, Y. & Yaghi, O. M. Covalent chemistry beyond molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3255–3265 (2016).

Li, H., Eddaoudi, M., O’Keeffe, M. & Yaghi, O. M. Design and synthesis of an exceptionally stable and highly porous metal-organic framework. Nature 402, 276–279 (1999).

Furukawa, H., Cordova, K. E., O’Keeffe, M. & Yaghi, O. M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 341, 974 (2013).

Ding, M., Flaig, R. W., Jiang, H.-L. & Yaghi, O. M. Carbon capture and conversion using metal-organic frameworks and MOF-based materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2783–2828 (2019).

Dalrymple, S. A. & Shimizu, G. K. H. Crystal engineering of a permanently porous network sustained exclusively by charge-assisted hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12114–12116 (2007).

Hisaki, I., Xin, C., Takahashi, K. & Nakamura, T. Designing hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs) with permanent porosity. Angew. Chem. 131, 11278–11288 (2019).

Cui, P. et al. An expandable hydrogen-bonded organic framework characterized by three-dimensional electron diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12743–12750 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Ethylene/ethane separation in a stable hydrogen-bonded organic framework through a gating mechanism. Nat. Chem. 13, 933–939 (2021).

Halliwell, C., Soria, J. F. & Fernandez, A. Beyond microporosity in porous organic molecular materials (POMMs). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217729 (2023).

Anupama, R., Burkhard, C. H., Ina, D. & Franc, M. A triazine-based three-directional rigid-rod tecton forms a novel 1D channel structure. Chem. Commun. 35, 3637–3639 (2007).

Yang, W. et al. Exceptional thermal stability in a supramolecular organic framework: porosity and gas storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14457–14469 (2010).

Bezzu, C. G. et al. Highly stable fullerene-based porous molecular crystals with open metal sites. Nat. Mater. 18, 740–745 (2019).

Meng, D. et al. Noncovalent π-stacked robust topological organic framework. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 20397–20403 (2020).

Eaby, A. C. et al. Dehydration of a crystal hydrate at subglacial temperatures. Nature 616, 288–292 (2023).

Little, M. A. & Cooper, A. I. The chemistry of porous organic molecular materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909842 (2020).

Sozzani, P., Bracco, S., Comotti, A., Ferretti, L. & Simonutti, R. Methane and carbon dioxide storage in a porous van der Waals crystal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 1816–1820 (2005).

Msayib, K. J. et al. Nitrogen and hydrogen adsorption by an organic microporous crystal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3273–3277 (2009).

Yamagishi, H. et al. Self-assembly of lattices with high structural complexity from a geometrically simple molecule. Science 361, 1242–1246 (2018).

Cai, S. et al. Hydrogen-bonded organic aromatic frameworks for ultralong phosphorescence by intralayer π-π interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4005–4009 (2018).

Zhang, L. et al. Phthalimide-based “D-N-A” emitters with thermally activated delayed fluorescence and isomer-dependent room-temperature phosphorescence properties. Chem. Commun. 55, 12172–12175 (2019).

Ishi-I, T., Tannka, H., Koga, H., Tanaka, Y. & Matsumoto, T. Near-infrared fluorescent organic porous crystal that responds to solvent vapors. J. Mater. Chem. C. 8, 12437–12444 (2020).

Tian, Y. et al. Organic microporous crystals driven by pure C-H···π interactions with vapor-induced crystal-to-crystal transformations. Mater. Horiz. 9, 731–739 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. A Noncovalent π-stacked porous organic molecular framework for selective separation of aromatics and cyclic aliphatics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201646 (2022).

Yamagishi, H. Functions and fundamentals of porous molecular crystals sustained by labile bonds. Chem. Commun. 58, 11887–11897 (2022).

Shen, Y. & Chen, C. Helicenes: synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 112, 1463–1535 (2012).

Dhbaibi, K., Favereau, L. & Crassous, J. Enantioenriched helicenes and helicenoids containing main-group elements (B, Si, N, P). Chem. Rev. 119, 8846–8953 (2019).

Lovinger, A. J., Nuckolls, C. & Katz, T. J. Structure and morphology of helicene fibers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 264–268 (1998).

Nakano, K., Oyama, H., Nishimura, Y., Nakasako, S. & Nozaki, K. λ5-Phospha[7]helicenes: synthesis, properties, and columnar aggregation with one-way chirality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 695–699 (2012).

Zeng, C. et al. Electron-transporting bis(heterotetracenes) with tunable helical packing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 10933–10937 (2018).

Wang, F., Gan, F., Shen, C. & Qiu, H. Amplifiable symmetry breaking in aggregates of vibrating helical molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16167–16172 (2020).

Shen, C. et al. Oxidative cyclo-rearrangement of helicenes into chiral nanographenes. Nat. Commun. 12, 2786–2793 (2021).

Spek, A. L. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Cryst. 36, 7–11 (2003).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Lu, T. & Chen, Q. Van der Waals potential: an important complement to molecular electrostatic potential in studying intermolecular interactions. J. Mol. Model. 26, 315 (2020).

Johnson, E. R. et al. Revealing noncovalent interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6498–6506 (2010).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD - visual molecular dynamics. J. Molec. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Willems, T. F., Rycroft, C. H., Kazi, M., Meza, J. C. & Haranczyk, M. Algorithms and tools for high-throughput geometry-based analysis of crystalline porous materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 149, 134–141 (2012).

Pinheiro, M. et al. Characterization and comparison of pore landspaces in crystalline porous materials. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 44, 208–219 (2013).

Ongari, D. et al. Accurate characterization of the pore volume in microporous crystalline materials. Langmuir 33, 14529–14538 (2017).

Wei, L. et al. Guest-adaptive molecular sensing in a dynamic 3D covalent organic framework. Nat. Commun. 13, 7936 (2022).

Heerden, D. P. & Barbour, L. J. Guest-occupiable space in the crystalline solid state: a simple rule-of-thumb for predicting occupancy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 735–749 (2021).

Cruickshank, A. J. B. & Cutler, A. J. B. Vapor pressure of cyclohexane, 25° to 75 °C. J. Chem. Eng. Data 12, 326–329 (1967).

Carl, G. V. J. & Joseph, J. M. Heat of vaporization and vapor pressure of 1,4-dioxane. J. Chem. Eng. Data 8, 74–75 (1963).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFA0908100, H.Q.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92056110, 22075180, H.Q.), the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (202101070002E00084, H.Q.), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (21XD1421900, H.Q.), the Science Foundation of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (22062026-Y, C.S.), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (LY23B040003, C.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z., C.S., and H.Q. conceived the project. G.Z., C.S., and F. G. synthesized the molecule and performed the X-ray crystal analysis. G.Z. collected the thermodynamic data. G.Z., Y.T. and Y.Z. conducted the sorption experiments. C.S. conducted the theoretical calculations and the data analysis. G.Z. and J.Z. performed the powder X-ray diffraction. G.Z., G.L., and J.L. acquired the SEM images. G.Z., C.S., and H.Q. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, commented on the manuscript and have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, G., Zhang, J., Tao, Y. et al. Facile fabrication of recyclable robust noncovalent porous crystals from low-symmetry helicene derivative. Nat Commun 15, 5469 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49865-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49865-y