Abstract

The utilization of low-energy photons in light-driven reactions is an effective strategy for improving the efficiency of solar energy conversion. In nature, photosynthetic organisms use chlorophylls to harvest the red portion of sunlight, which ultimately drives the reduction of CO2. However, a molecular system that mimics such function is extremely rare in non-noble-metal catalysis. Here we report a series of synthetic fluorinated chlorins as biomimetic chromophores for CO2 reduction, which catalytically produces CO under both 630 nm and 730 nm light irradiation, with turnover numbers of 1790 and 510, respectively. Under appropriate conditions, the system lasts over 240 h and stays active under 1% concentration of CO2. Mechanistic studies reveal that chlorin and chlorinphlorin are two key intermediates in red-light-driven CO2 reduction, while corresponding porphyrin and bacteriochlorin are much less active forms of chromophores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light-driven reduction of CO2 (CO2RR) into valuable chemicals has been considered as a promising approach in the direct utilization of solar energy1,2,3,4,5,6. Great progress has been achieved in the study of photochemical CO2RR using the high-energy portion of sunlight7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. However, the development of catalytic systems performing under the irradiation of low-energy light (red and near-infrared) remains a significant challenge. Under AM1.5G, the maximum harvestable photons below 600 nm is ~19%18. Thus, there is increasing enthusiasm in seeking photocatalytic systems for the utilization of low-energy photons in the solar spectrum.

Chromophores that have been demonstrated to utilize low-energy photons for catalytic CO2RR are rarely reported in the literature, all of which are based on the most precious metals. A frequent difficulty is that molecules absorbing at long wavelengths often generate insufficient reduction potentials to overcome the large driving forces in CO2RR. In 2013, Ishitani and co-workers reported the first molecular system for red-light-driven CO2RR using Os−Re supramolecular complexes, achieving a turnover number (TON) of 1138 with >620 nm light19. Recently, a photochemical system using a heteroleptic Os(II) chromophore and a Ru(II) catalyst was developed for CO2RR to generate HCOOH under irradiation with 725 nm light (TON = 81)20. Furthermore, a Zn porphyrin-sensitized Mn(I) system was demonstrated to reduce CO2 under 625 nm light, however, its TONCO was lower than 121.

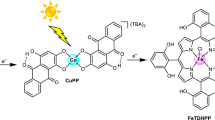

Porphyrin-based compounds have been widely used as blue-light absorbers in artificial photosynthetic systems, either for the reductive-half 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 or for the overall reactions31,32,33. However, chlorin (Ch), which is a reduced porphyrin adapted by most of the chlorophylls in plants and cyanobacteria (Fig. 1) for harvesting red-light34,35,36,37, has not been reported in such a context. The Ch can undergo a 2e−/2H+ reduction photochemically to generate a chlorinphlorin (ChPh)38,39,40,41,42,43, which exhibits a broad absorption spectrum into the near-infrared region44,45,46, as recently determined by Nocera and co-workers47. The optical and redox properties of Chs highly suggest that they may serve as active chromophores for red-light-driven CO2RR. Here, we present a series of fluorinated Chs (Fig. 1) as chromophores for red-light-driven CO2RR in precious-metal-free systems. The structure-function study demonstrates that increasing the number of fluorine substituents on the meso-phenyl group of Ch significantly enhances the activity of CO2RR. The systems using a per-fluorinated Ch last over 240 h and give high TONs of 1790 (at 630 nm) and 510 (at 730 nm) in the conversion of CO2 to CO.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and photophysical properties

A library of fluorinated meso-tetraphenyl porphyrins (FxTPP) and chlorins (FxCh) (x = 0, 4, 12, 20; Fig. 1) were prepared according to procedures described in the “Methods” section. A per-fluorinated bacteriochlorophyll (F20BC, Fig. 1) was synthesized by further reduction of F20Ch and crystallographically determined (Supplementary Information). In contrast to FxTPP, all FxCh display strong absorption profiles for red light in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) (Supplementary Figs. 2–6). Increasing the number of the fluorine substituents on FxCh shows a general impact on the absorption band at the red-light region, by slightly red-shifting the maximum absorption from 650 to 654 nm, as well as increasing the extinction coefficient (ε) from 3.458 × 104 to 5.125 × 104 M−1 cm−1 (Table 1). All chlorins exhibit an intense Soret (B) bond (from 405 to 420 nm) and 4 to 5 Q bands (from 504 to 654 nm). As would normally be anticipated for chlorins48,49,50,51, red-shift and the higher extinction coefficient for the Q band between 650 and 654 nm than those observed for corresponding FxTPP.

Light-driven CO2RR

The light-driven properties of these macrocyclic chromophores were evaluated in a well-studied CO2RR system in our laboratory, by using an iron (III) tetrakis (2’,6’-dihydroxyphenyl)-porphyrin (FeTDHPP) as the catalyst and 1,3-dimethyl-2-phenyl benzimidazoline (BIH) as the electron donor52,53. The system containing these three components in a CO2-saturated DMF solution was irradiated using a red light-emitting diode (λmax = 630 or 730 nm, Supplementary Fig. 8), and the gaseous products generated were measured in real-time by gas chromatography (GC).

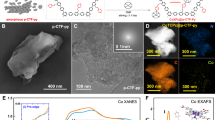

We first examined the activity of a simple meso-tetraphenyl porphyrin F0TPP for red-light-driven CO2RR. In a system (50 μM F0TPP, 1.0 μM FeTDHPP, 50 mM BIH, 630 nm light), only a small amount (0.02 μmol) of CO corresponding to a TON of 4.0 was detected. We found that replacing F0TPP with F0Ch in the system resulted in a >52-fold increase of TON at 630 nm (Fig. 2a). A remarkable observation for both FxTPP and FxCh is the increases in CO2RR activity with more fluorine substituents on the chromophore (Fig. 2a–c, and Table 1). With the per-fluorinated chlorin F20Ch, the system achieves a high TON of 1790 ± 52 after 51 h of irradiation, an initial turnover frequency (TOF) up to 194 ± 9 h−1, and a quantum yield of 0.88 ± 0.03% at 630 nm (Supplementary Table 3). The TON described here is significantly higher than those reported for red-light-driven CO2RR (homogeneous and heterogeneous) systems including the ones using noble metals (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

a Comparing the overall TONCO of systems with different FxTPP and FxCh. b TONCO for systems with different FxTPP. c TONCO for systems with different FxCh. d CO generation for systems with different initial [F20Ch] and [FeTDHPP]. e stability of a system with F20Ch, f CO2RR under 1% or 5% concentrations of CO2 with F20Ch. Error bars denote standard deviations. TON calculated based on [FeTDHPP]. Catalytic conditions: a–c used 50 μM FxTPP or FxCh, 1.0 μM FeTDHPP, and 50 mM BIH; d used the same concentrations (1, 2, 5, 10 μM) of F20Ch and FeTDHPP, 50 mM BIH; e used 100 μM F20Ch, 100 μM FeTDHPP, and 200 mM BIH; f used 100 μM F20Ch, 100 μM FeTDHPP, and 50 mM BIH; Experiments were in CO2-saturated DMF (5.0 mL) at 20 °C using a light-emitting diode (LED) source (λ = 630 nm, 110 mW/cm2). The profiles and data of TOF for (b–e) were shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, Table 1, and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

We further found that the initial rates of CO production followed a first-order dependence on both concentrations of chromophore and catalyst (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). Based on the observation, we hypothesized that high TONs for both chromophore and catalyst could be realized in one system, which would be beneficial for the development of versatile light-driven and light-electricity-driven systems. Indeed, when the CO2RR experiments were conducted under the same concentration of F20Ch and FeTDHPP, a high TON of 1404 was obtained after 147 h (Supplementary Table 4).

In all the red-light-driven experiments performed under an atmosphere of CO2, no other gaseous product was observed by GC. Analysis of the liquid phase by 1H NMR showed no detection of formic acid and methanol. To study the selectivity of the system further, we found that the amounts of CO generated were near the theoretical maximum value (Supplementary Fig. 13) of the electron donor BIH (based on two electrons per BIH molecule), which suggests that the selectivity of CO is nearly 100%.

We note that both the stability of the system and the amount of produced CO are significantly improved at higher concentrations of F20Ch and FeTDHPP (Fig. 2d). To study stability and scalability of the system further, we found that the photocatalysis lasted over 240 h and produced over 608 μmol CO when the experiments were conducted at 0.1 mM F20Ch and FeTDHPP (Fig. 2e). The slight decrease of the initial catalytic rate is presumably due to consumption of CO2 during CO2RR. Indeed, we observed slower rates of CO generation from mixtures at lower concentrations of CO2 (Fig. 2f). However, its ability to function at low CO2 contents (down to 1%) with high selectivity (97.7% under 5% CO2 and 95.6% under 1% CO2) was impressive.

To study the nature of the system, various control experiments were performed. We observed no CO generated from a light-driven system carried out under an atmosphere of N2, which implied that CO was derived from CO2. Isotopic labeling experiments conducted under 13CO2 produced 13CO as detected by GC-MS (Supplementary Fig. 14). This result thus further confirms that CO2 is the carbon source in catalysis. In addition, a negligible amount of CO detected in the absence of FxCh, FeTDHPP, BIH, light, or under Ar (Supplementary Table 6) suggests that all components are essential for the light-driven CO2RR. To rule out potential metal contaminants, inorganic salts (Fe3+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Co3+, Ru3+, Pd2+) with or without TDHPP ligand all produced no or negligible amount of CO as compared with the experiment using FeTDHPP as the catalyst (Supplementary Table 7). Photolysis performed using chemicals that passed the elemental analysis or using FeTDHPP synthesized from highly pure FeBr2 all showed identical activity (Supplementary Fig. 15). Furthermore, experiments conducted in the presence of an excess amount of Hg0 showed an identical activity profile (Supplementary Fig. 16), indicating no contamination from amalgam-forming metals. Dynamic light-scattering measurements showed the absence of nanoparticles in the CO2RR systems before and after light irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Mechanistic study

To gain mechanistic insight into the red-light-driven system, we next sought to identify the active intermediates in CO2RR. Under Ar or N2, the cyclic voltammogram (CV) of F0Ch in DMF shows two reversible redox events at –1.11 and –1.58 V vs SCE (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 18, and Table 1), corresponding to the generation of one and two electrons reduced Chs (F0Ch– and F0Ch2–)39. For the fluorinated Chs, these two reduction potentials shift towards more positive (by over 300 mV for F20Ch) due to the electron-withdrawing effects of the fluorine substituents (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 19, and Table 1). Similar CV spectra were obtained in experiments conducted in the presence of 1% H2O (Supplementary Fig. 20). Because CO2RR has to occur at an Fe(0) state of FeTDHPP at –1.55 V vs SCE54,55,56, a more reducing form of chromophore other than FxCh– and FxCh2– must be involved in the photochemical scheme. Indeed, the CV, obtained under an atmosphere of CO2 and in the presence of H2O as the proton source, revealed the appearance of a new reduction wave at a potential more negative than –1.6 V (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 21, and Table 1). A similar observation was obtained when using either trifluoro ethanol or acetic acid as the proton donor (Supplementary Figs. 22–26). In these experiments, the increase of the first reduction wave and the decrease of the second reduction wave suggests the generation of FxChPh (Fig. 4) through two subsequent proton-coupled electron transfer47. Therefore, the wave at <–1.6 V is ascribed to further reduction of FxChPh to FxChPh– (Fig. 4), which is thermodynamically favorable in reducing FeTDHPP to the required Fe(0) intermediate for CO2RR.

We gained further evidence of the FxChPh species using ultraviolet-visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy. By photolyzing a solution containing F0Ch and BIH for a few minutes, we observe a broad absorption peak (from ~450 nm to 850 nm) that corresponds to a 2e–/2H+ photoproduct F0ChPh (Supplementary Fig. 27)39,46,47. Consistent with this result, similar broad spectra are observed in the reduction of other FxCh (Supplementary Figs. 28–30). In addition, most of the F0Ch can be recovered in a reverse 2e–/2H+ oxidative process by exposing the photolyzed solution to the air (Supplementary Fig. 27c).

We next examined the UV–vis spectra of the catalytic solutions (containing F0Ch or F20Ch, FeTDHPP, and BIH) during photolysis (Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32). The broad spectra corresponding to FxChPh were again quickly generated within minutes. Continued irradiation resulted in a slow decrease of FxChPh during CO2RR, suggesting a further reduction of FxChPh to FxChPh–. By keeping the photolyzed F20Ch-containing system in the dark, we observed recovery of F20ChPh and generation of F20Ch and F20BC in the solution (Supplementary Fig. 33), as well as an additional 0.66 ± 0.03 equiv of CO in the headspace (Supplementary Table 8). These findings thus suggest that both photochemical conversion of FxChPh to FxChPh– (through reductive quenching) and electron transfer from FxChPh– to FeTDHPP (to generate the Fe(0) intermediate) are the two key steps in CO2RR (Fig. 4).

We performed additional experiments to study whether FxChPh– is also involved in red-light-harvesting in CO2RR. Because it exhibits absorption up to ~600 nm (Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32), the corresponding photochemical pathway in CO2RR should be terminated by using a light source with longer wavelengths. We found that all four FxCh were active in producing CO over 170 h under irradiation with 730 nm LEDs (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 34). In the series, the system with F20Ch gave the highest TONCO of 510. This suggests that FxChPh instead of FxChPh– is responsible for absorbing red light in CO2RR.

To evaluate the stability of FxCh during CO2RR, we quenched the photolysis by treatment of the catalytic solution first using a Co(III) dimethylglyoximate complex and then exposure to the air. For the F0Ch-containing system, UV–vis spectra revealed a 71% decrease of F0Ch and a significant increase of the F0BC after 75 h irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 35). In comparison, 51% of F20Ch was recovered and a relatively small amount of F20BC was observed (Supplementary Fig. 36). These results imply that cessation of CO2RR under these conditions may be due to complete decomposition of FeTDHPP. In fact, at a higher [FeTDHPP], the lifetime of the system is significantly prolonged (Fig. 2d, e), as described above. Furthermore, addition of FeTDHPP to a photolysis system at 51 h completely restored the activity (Supplementary Fig. 37), which confirms that deactivation of FeTDHPP is a limiting factor in the lifetime of the system.

To understand the very different activity between FxTPP and FxCh, we examined the photochemical steps of FxTPP in CO2RR. For the least active chromophore F0TPP, no conversion to F0Ch was observed during photolysis (Supplementary Fig. 38). In its quenched reaction mixture, we found that most of the F0TPP was recovered after 4 h irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 39). However, for other fluorinated TPP, FxCh intermediates can be observed unambiguously (Supplementary Figs. 40–42). Furthermore, a significant conversion of F20TPP to F20Ch was observed (Supplementary Fig. 43), which might explain the much higher activity observed with F20TPP in the series. This evidence suggests that the fluorine substituents on TPP facilitate isomerization from phlorin (a 2e–/2H+ reduced porphyrin, defined as FxPh) to Ch (Fig. 4), and such transformation is an essential pathway when using FxTPP as the chromophore for red-light-driven CO2RR.

Because FxBC (presumably isomerized from FxChPh) is present in the quenched photolysis mixtures, we study its impact on CO2RR with an independently synthesized F20BC. The crystal structure of F20BC shows two characteristic C–C single bonds in the pyrrole ring, which exhibit similar distances compared with reported Ch and bacteriochlorins (BC) compounds (Supplementary Table 10)57,58. Under the same conditions, the system with F20BC exhibits a much lower initial TOF (60 h−1) than that with F20Ch (Supplementary Fig. 44). UV–vis study shows no detection of F20Ch in both the photocatalytic and the quenched solutions (Supplementary Figs. 45 and 46). Hence, the irreversible isomerization from FxChPh to FxBC (Fig. 4) during photolysis might also lead to a decrease of CO2RR activity when using FxCh as the chromophores.

Previous studies showed that BIH functioned as a 2e–/1H+ donor59,60. To generate the BI-radical (which donates the second e–), deprotonation of the BIH-radical cation by a base such as triethylamine (TEA) was found to be necessary in acetonitrile (ACN) (Supplementary Table 11). However, there are several photocatalytic studies reported in DMF without TEA or additional bases when using BIH as the electron donor53,61,62. To investigate this, we performed CV studies for BIH in DMF and ACN (Supplementary Figs. 47–48). In contrast to the voltammograms in ACN, the CV in DMF showed appearance of a reduction wave at ~ –1.6 V vs SCE, corresponding to generation of the BI-radical. This result suggests that deprotonation of the BIH-radical cation is more favorable in DMF than in ACN. However, addition of TEA to the system was found to improve the activity (Supplementary Fig. 49 and Supplementary Table 11), exhibiting a TONCO of 2132 in 27 h and an initial TOFCO of 584 h−1. In the overall reactions, BI+ and OH– were produced in generation of the 2e–/2H+ reduced chromophores and in CO2 reduction (Eqs. 1 and 2).

The photocatalytic CO2 reduction mechanism by FeTDHPP has been extensively investigated by Robert and co-workers63,64,65. UV–vis studies showed generation of the corresponding Fe(II) and Fe(I) species at the early stage of photolysis (Supplementary Figs. 50–53). The Fe(I) species was found to decrease during CO production, which indicates a catalytic cycle consistent with previous reports (Fig. 4)52,64,65. No electrostatic interaction was found between the chlorin and FeTDHPP by UV–vis studies (Supplementary Fig. 54), which suggests electron transfer from the chromophore to the catalyst follows an outer-sphere mechanism.

Overall, red-light-driven reduction of CO2 was achieved using a series of synthetic porphyrin-based chromophores in precious-metal-free systems. Conversion of TPP to Ch and ChPh has been identified as an important photochemical pathway in CO2RR. Fluorination of the light-harvesting macrocycle has been demonstrated to be an effective method both in facilitating such transformation and in promoting the catalytic activity. In light of the high TON, long-term stability, and selectivity of the systems, we anticipate that this study maps a route for the development of efficient CO2RR systems using low-energy sunlight.

Methods

Materials

All solvents and reagents were commercially purchased and used as received without further purification unless otherwise noted. FeTDHPP was prepared following a reported procedure using FeCl2•4H2O and FeBr256, analysis (calcd., found for C44H28ClFeN4O8•1.7H2O•C6H14(Hex)): C (63.29, 63.39), H (4.82, 5.11), N (5.90, 5.70).

DMF (Energy chemical, 99.8%, distilled, extra dry with molecular sieves, water ≤50 ppm (by K.F.)) was purchased from Anhui Zesheng Technology Co., Ltd (Anuhi, China); Anhydrous K2CO3 (GREAGENT, ≥99.0%) was purchased from Guangzhou beier biological Technology Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China); p-Toluenesulfonyl hydrazide (Macklin, 98%) was purchased from Guangzhou Sopo biological Technology Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China); Dry pyridine (Acseal, 99.5%, with molecular sieves, water ≤50 ppm (by K.F.)) was purchased from Shanghai Jizhi Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China); 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-benzoquinone (DDQ, Energy chemical 98%) was purchased from Anhui Zesheng Technology Co., Ltd (Anuhi, China); Benzaldehyde (innochem, 98%); 2-Fluorobenzaldehyde (BIDE, 98%); 2,4,6-Trifluorobenzaldehyde (BIDE, 98%); Pentafluorobenzaldehyde (macklin, 98%); 2,6-Dimethoxybenzaldehyde (BIDE, 98%); Boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (Aladdin, BF3: 46.5%); Pyrrole (Energy chemical, 99%); Co(NO3)3•6H2O (damas-beta, 99.0%); Fe(NO3)3•9H2O (Guangzhaou, ≥98.5%); Cu(NO3)2•9H2O (Kermel, 99.0–102.0%); Ni(NO3)2•6H2O (Xiya, 99%); RuCl3•xH2O (Aladdin, 35.0–42.0% Ru basis); FeCl2•4H2O (Guangzhaou, 99.5−101.0%); FeBr2 (Rhawn, 99.995% metals basis); Pd(OAc)2 (Eybridge, 98%); Dichloromethane (WOHUA-CHEMICAL, 99.5%); Petroleum ether (PE, WOHUA-CHEMICAL, 99.5%); Ethyl acetate (WOHUA-CHEMICAL, 99.5%); n-Hexane (HD, 99.5%).

Preparation of Co(dmgH)2PyCl

Co(dmgH)2PyCl was synthesized following a modified procedure based on previous report66. CoCl2·6H2O (2.15 mmol, 500 mg) was dissolved in 200 mL ethanol and heated to 70 °C, then dimethylglyoxime (4.70 mmol, 551 mg) was added. After 10 min of stirring, pyridine (4.30 mmol, 344 mg) was added drop by drop to the mixture and air was bubbled through the solution for 30 min. The yellow precipitate was collected by filtration and washed with deionized water, ethanol, and diethyl ether, and dried under vacuum. Large yellow block crystals were obtained from acetonitrile by slow evaporation at ambient temperature (75% yield). Co(dmgH)2PyCl was evidenced by 1H NMR (Supplementary Fig. 86).

Preparation of BIH

BIH was prepared based on modified methods in the literature67. 2-Phenylbenzimidazole (30.91 mmol, 6.00 g) was dissolved in 30 mL methanol solution containing NaOH (32.00 mmol, 1.28 g), then methyl iodide (112.38 mmol, 7 mL) was added to the above solution and the mixture was heated at 100 °C for 24 h in the dark. After cooling to room temperature, the faint yellow solid (BIH+I−) was collected by filtration and washed with EtOH/H2O (5:1, v/v). Then, a solution of BIH+I− (8.57 mmol, 3.00 g) in methanol (80 mL) was added slowly with NaBH4 (89.47 mmol, 3.40 g) under N2 and the mixture was allowed to react for 3 h. The resulting solution was evaporated to obtain a white solid. The white solid (BIH) was purified by washing with plenty of water. The yield was 90%. BIH was evidenced by 1H NMR (Supplementary Fig. 84) and elemental analysis (calcd., found for C15H16N2): C (80.32, 80.20), H (7.19, 7.26), N (12.49, 12.42).

Preparation of F0TPP

F0TPP was prepared according to a method in the literature68. Pyrrole (0.36 mol, 25 mL) and benzaldehyde (0.38 mol, 40 mL) were dissolved in propionic acid (250 mL) and refluxed for 45 min. When the resulting solution was cooled to ambient temperature, a purple solid was collected by filtration, washed with methanol, and dried under vacuum. The yield was 80%. F0TPP was evidenced by 1H NMR (Supplementary Fig. 66) and elemental analysis (calcd., found for C44H30N4•0.8H2O): C (84.00, 84.00), H (5.06, 5.07), N (8.91, 8.81).

Preparation of F4TPP

F4TPP was synthesized based on modified methods in the literature69. Pyrrole (0.05 mol, 3.355 g) and 2-fluorobenzaldehyde (0.05 mol, 6.205 g) were added dropwise simultaneously to a boiling propionic acid (200 mL) and the mixture was refluxed for another 30 min. When the resulting solution was cooled to ambient temperature, a purple product (16% yield) was obtained by filtration, and washed with methanol then dried under vacuum. F4TPP was evidenced by 1H NMR, 19F NMR (Supplementary Figs. 67 and 68) and elemental analysis (calcd., found for C44H26F4N4•0.3H2O): C (76.36, 76.49), H (3.87, 4.18), N (8.10, 8.06).

Preparation of F12TPP and F20TPP

F12TPP and F20TPP were synthesized according to modified methods from the literature70. 2,4,6-Trifluorobenzaldehyde (13.00 mol, 2.080 g) or pentafuorobenzaldehyde (13.00 mol, 2.548 g) was dissolved in 500 mL dichloromethane (DCM), followed by addition of pyrrole (13.00 mmol, 905 μL). After the mixture was stirred and degassed by N2 for 20 min, BF3·Et2O (3.90 mmol, 1.1 mL) was added via a syringe. After 2 h, TEA (7.80 mmol, 1.0 mL) was added to neutralize excessive acid, then DDQ (13.65 mmol, 3.100 g) was added and the resulting mixture was stirred for an additional 1 h. The residues were purified by column chromatography on silica gel eluted with Hex/DCM (VHex:VDCM = 4:1). Both yields for F12TPP and F20TPP are 24%. F12TPP and F20TPP were all evidenced by 1H NMR, 19F NMR (Supplementary Figs. 69–72) and elemental analysis. F12TPP: analysis (calcd., found for C44H18F12N4•0.3H2O): C (63.21, 63.49), H (2.24, 2.59), N (6.70, 6.77). F20TPP: analysis (calcd., found for C44H10F20N4•0.7H2O•0.1C6H14 (0.1 Hex)): C (53.80, 53.85), H (1.30, 1.31), N (5.63, 5.81).

Preparation of FxChs

FxChs were synthesized based on modified methods in the literature48,49. Note: the chlorin-based compounds F0Ch48, F20Ch71, and F20BC72 have been previously reported. F4Ch and F12Ch are new compounds.

For F0Ch, F4Ch, and F12Ch: The corresponding porphyrin (0.50 mmol), p-toluenesulfonylhydrazine (TSH, 2.00 mmol, 373 mg), and anhydrous K2CO3 (5.00 mmol, 691 mg) were dissolved in dry pyridine (50 mL). The mixture was heated at 105 °C under N2 in the dark for 12 h, during which TSH (2.00 mmol, 373 mg) was added every 3 h. For F20Ch: F20TPP (0.51 mmol, 497 mg), TSH (2.55 mmol, 475 mg), and anhydrous K2CO3 (2.75 mmol, 380 mg) were dissolved in dry pyridine (50 mL) and the mixture was heated at 105 °C for 4 h under N2 in the dark.

Purification procedure: After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was added to 200 mL water and then extracted with DCM. The extracted organic portion was washed with 2 M HCl (3 times), saturated sodium bicarbonate aqueous solution (2 times) and deionized water (3 times). Appropriate amounts 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-benzoquinone (DDQ, 1 mg/mL) in DCM were slowly added to the collected DCM layer until the characteristic absorption of the over-reduced product at ~740 nm (for synthesis of F0Ch and F4Ch), ~744 nm (for synthesis of F12Ch), ~748 nm (for synthesis of F20Ch) disappeared. The solvent was removed and the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using DCM (for purification of F0Ch, F4Ch, and F12Ch) or PE/DCM (VPE:VDCM = 50:1) (for purification of F20Ch) as the eluent to give the corresponding chlorin, which were characterized by 1H NMR, and/or 13C NMR and/or 19F NMR spectra, C/H/N elemental analysis, and HRMS.

F0Ch: (yield: 57%), 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.56 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 8.41 (s, 2H), 8.17 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 8.10 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.7 Hz, 4H), 7.93–7.84 (m, 4H), 7.67 (dt, J = 8.8, 4.5 Hz, 12H), 4.16 (s, 4H), −1.43 (s, 2H); HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for [C44H33N4]+, 617.26997; found, 617.26898; analysis (calcd., found for C44H32N4•0.4H2O): C (84.70, 84.77), H (5.30, 5.47), N (8.98, 8.96).

F4Ch: (yield: 17%), 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.57 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 8.40 (s, 2H), 8.22 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 8.10 −7.95 (m, 2H), 7.83 (dt, J = 15.6, 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7 7.70 (m, 4H), 7.46 (m, 8H), 4.28–4.13 (m, 4H), −1.44 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.10, 162.63 (m), 161.00 (m), 152.58, 140.58, 135.75 (m), 135.25, 134.82 (m), 131.95, 130.35 (d, J = 7.7 Hz), 130.21 (d, J = 8.2 Hz), 130.11 (d, J = 17.5 Hz), 129.50 (d, J = 16.5 Hz), 127.95, 124.13 (m), 123.36, 122.93 (m), 116.16 (m), 115.55, 115.29 (m), 105.69, 35.38; 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −111.29– −112.26 (m, 2F), −112.67– −113.58 (m, 2F); HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for [C44H29F4N4]+, 689.23229; found, 689.23102; analysis (calcd., found for C44H28F4N4•0.4H2O): C (75.94, 75.67), H (4.17, 4.45), N (8.05, 7.97).

F12Ch: (yield: 70%), 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.64 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 8.45 (s, 2H), 8.30 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 7.11 (dt, J = 8.5, 4.0 Hz, 8H), 4.25 (s, 4H), −1.47 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.87, 164.18 (m), 163.10 (m), 162.51 (m), 161.44 (m), 152.76, 140.52, 135.40, 131.87, 127.88, 123.24, 115.39 (m), 115.06 (m), 107.97, 101.02 (m), 100.32 (m), 98.27, 35.15; 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −105.52 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 4F), −106.57 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2F), −106.66–−106.88 (m, 6F); HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for [C44H21F12N4]+, 833.15691; found, 833.15497; analysis (calcd., found for C44H20F12N4): C (63.47, 63.50), H (2.42, 2.60), N (6.73, 6.77).

F20Ch: (yield: 21%), 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.68 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 8.45 (s, 2H), 8.35 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 4.31 (s, 4H), −1.53 (s, 2H); 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −136.83–−137.13 (m, 4F), −137.91 (dd, J = 23.9, 8.5 Hz, 4F), −152.02 (dt, J = 85.0, 20.9 Hz, 4F), −160.69 (m, 4F), −161.60 (m, 4F); HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for [C44H13F20N4]+, 977.08154; found, 977.07904; analysis (calcd., found for C44H12F20N4): C (54.12, 54.42), H (1.24, 1.54), N (5.74, 5.94).

Preparation of F20BC

F20BC was synthesized based on a modified method in the literature72. F20TPP (0.13 mmol, 125 mg,) and TSH (3.90 mmol, 740 mg) were added to a mortar, and then grinded evenly. The powder was put into a Schlenk flask and kept under vacuum for 12 h. Subsequently, the mixture was heated to 160 °C and kept for 30 min. After cooled to room temperature, the mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography using PE/DCM (VPE:VDCM = 20:1) as the eluent and washed with Hex to obtain the corresponding F20BC (8% yield). Recrystallization of F20BC by vapor diffusion of Hex into a chloroform solution gave block green crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis. F20BC were evidenced by 1H NMR, 19F NMR (Supplementary Figs. 82 and 83) and elemental analysis (calcd., found for C44H14F20N4•0.3C6H14 (0.3 Hex)): C (54.77, 54.79) H (1.83, 1.91), N (5.58, 5.61).

Characterization

1H NMR and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker advance III 400-MHz NMR instrument at room temperature. UV–vis spectra were acquired using a Thermo Scientific GENESYS 50 UV-visible spectrophotometer. HRMS spectra were collected on a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Q Exactive ion trap mass spectrometer. Dynamic light scattering experiments were conducted with a Brookhaven Elite Sizer zata-potential and a particle size analyzer. C/H/N analysis for all the photosensitizers, catalyst, and electron donor were recorded on vario EL cube elemental analyzer.

Photocatalytic CO2 reduction

A typical photocatalytic CO2 reduction experiment was carried out in a glass vial (56.8 mL) upon successive addition of DMF solution (5 mL) containing BIH, FeTDHPP, and the chromophore. The glass vial equipped with a magnetic stirrer was sealed with an airtight rubber plug and purged with CO2 for at least 25 min. The reaction sample was then irradiated with a red LED light setup (λ = 630 nm or 730 nm, PCX-50C, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd.). The gaseous products in the headspace were analyzed by Shimadzu GC-2014 gas chromatography equipped with Shimadzu Molecular Sieve 13X 80/100 3.2 × 2.1 mm × 3.0 m and Porapak N 3.2 × 2.1 mm × 2.0 m columns. A thermal conductivity detector (TCD) was used to detect H2 and a flame ionization detector (FID) with a methanizer was used to detect CO and other hydrocarbons. Nitrogen was the carrier gas. The oven temperature was kept at 60 °C. The TCD detector and injection port were kept at 100 °C and 200 °C, respectively. 13C isotopic labeling experiments were conducted in a 13CO2 atmosphere and the gas products were analyzed by GC-MS (Thermo Scientific TSQ Quantum XLS).

Photolysis quenching

During photolysis, 2.52 μmol Co(dmgH)2PyCl in DMF (210 μL) was injected into a photocatalytic solution under N2 and the mixture was allowed to stir for 3 h in the dark. The mixture was then exposed to the air for 1 h and analyzed by UV–vis spectroscopy. Direct exposure of the reaction mixture to the air led to complicated oxidized species with unidentified UV–vis spectra.

Electrochemical measurements

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and square wave voltammetry (SWV) were performed on a CHI-760E electrochemical workstation, using a glassy carbon working electrode (diameter 3 mm), Pt auxiliary electrode, and a SCE reference electrode. The electrolyte was 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) in DMF or DMF/H2O. The solution was purged with N2 or CO2 at least 20 min before measurements. All reported potentials in this work are versus SCE.

Fluorescence and excited-state lifetime determination

A solution of the chromophore in a closed quartz cuvette with a septum cap was purged with N2 for at least 15 min. The steady-state fluorescence was recorded on the Duetta fluorescence and absorbance spectrometer. The excited-state lifetimes (τ0) of FxCh were measured with an FLS 980 or FLS 1000 fluorescence spectrometer (Edinburgh instruments), in which a picosecond pulsed diode laser (λ = 472 nm) (Edinburgh instruments EPL470) was used as the excitation source.

Quantum yield measurement

The experiments were conducted on 630 nm LED light. The blank was a DMF solution containing 5 µM FeTDHPP, and 50 mM BIH. The difference between the power (P) of light passing through the blank and through the sample containing FxCh (x = 0, 4, 12, 20) was measured with a FZ-A Power meter (Beijing Normal University Optical Instrument Company). The quantum yield (Φ) was calculated according to the Eq. (3):

that is,

where n(CO) is the number of molecules of CO produced, I is the number of incident photons; I can be calculated by the Eq. (5):

S is the incident irradiation area (S = 6.33 cm2), t is the irradiation time (in second), λ is the wavelength of the light (630 nm), h is the Plank constant (6.626 × 10−34 J·s), and c is the speed of light propagation (3 × 108 m·s−1).

where NA is the Avogadro constant (6.02 × 1023 mol−1).

X-ray crystallography

X-ray diffraction data were collected on SuperNova single crystal diffractometer using the CuKα (1.54184 nm) radiation at 150 K. Absorption correction was carried out by a multiscan method. The crystal structure was solved by direct methods with SHELXT73 program, and was refined by full-matrix least-square methods with SHELXL73 program contained in the Olex2-1.574. Weighted R factor (Rw) and the goodness of fit S were based on F2, conventional R factor (R was based on F (Supplementary Table 9). Hydrogen atoms were placed with the AFlX instructions and were refined using a riding mode. Figures were drawn with Diamond software.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request. The X-ray crystallographic data for F20BC reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2289797. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Aresta, M., Dibenedetto, A. & Angelini, A. Catalysis for the valorization of exhaust carbon: from CO2 to chemicals, materials, and fuels. Technological use of CO2. Chem. Rev. 114, 1709–1742 (2013).

Lewis, N. S. & Nocera, D. G. Powering the planet: chemical challenges in solar energy utilization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15729–15735 (2006).

Gray, H. B. Powering the planet with solar fuel. Nat. Chem. 1, 7 (2009).

Nocera, D. G. Solar fuels and solar chemicals industry. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 616–619 (2017).

Morris, A. J., Meyer, G. J. & Fujita, E. Molecular approaches to the photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide for solar fuels. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1983–1994 (2009).

Wang, Q., Pornrungroj, C., Linley, S. & Reisner, E. Strategies to improve light utilization in solar fuel synthesis. Nat. Energy 7, 13–24 (2021).

Zhang, B. & Sun, L. Artificial photosynthesis: opportunities and challenges of molecular catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2216–2264 (2019).

Dalle, K. E. et al. Electro- and solar-driven fuel synthesis with first row transition metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 119, 2752–2875 (2019).

Boutin, E. et al. Molecular catalysis of CO2 reduction: recent advances and perspectives in electrochemical and light-driven processes with selected Fe, Ni and Co aza macrocyclic and polypyridine complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 49, 5772–5809 (2020).

Luo, Y.-H., Dong, L.-Z., Liu, J., Li, S.-L. & Lan, Y.-Q. From molecular metal complex to metal-organic framework: the CO2 reduction photocatalysts with clear and tunable structure. Coord. Chem. Rev. 390, 86–126 (2019).

Yin, H. Q., Zhang, Z. M. & Lu, T. B. Ordered integration and heterogenization of catalysts and photosensitizers in metal-/covalent-organic frameworks for boosting CO2 photoreduction. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 2676–2687 (2023).

Rahaman, M. et al. Solar-driven liquid multi-carbon fuel production using a standalone perovskite–BiVO4 artificial leaf. Nat. Energy 8, 629–638 (2023).

Xie, W. et al. Metal-free reduction of CO2 to formate using a photochemical organohydride-catalyst recycling strategy. Nat. Chem. 15, 794–802 (2023).

Huang, H.-H. et al. Dual electronic effects achieving a high-performance Ni(II) pincer catalyst for CO2 photoreduction in a noble-metal-free system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2119267119 (2022).

Yuan, H. et al. Combination of organic dye and iron for CO2 reduction with pentanuclear Fe2Na3 Purpurin Photocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4305–4309 (2022).

Guo, Z. et al. Selectivity control of CO versus HCOO− production in the visible-light-driven catalytic reduction of CO2 with two cooperative metal sites. Nat. Catal. 2, 801–808 (2019).

Wang, J.-W. et al. Boosting CO2 photoreduction by π–π-induced preassembly between a Cu(I) sensitizer and a pyrene-appended Co(II) catalyst. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2221219120 (2023).

Smestad, G. P. et al. Reporting solar cell efficiencies in solar energy materials and solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 92, 371–373 (2008).

Tamaki, Y., Koike, K., Morimoto, T., Yamazaki, Y. & Ishitani, O. Red-light-driven photocatalytic reduction of CO2 using Os(II)–Re(I) supramolecular complexes. Inorg. Chem. 52, 11902–11909 (2013).

Irikura, M., Tamaki, Y. & Ishitani, O. Development of a panchromatic photosensitizer and its application to photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Chem. Sci. 12, 13888–13896 (2021).

Shipp, J. et al. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO in aqueous solution under red-light irradiation by a Zn-porphyrin-sensitized Mn(I) catalyst. Inorg. Chem. 61, 13281–13292 (2022).

Nikoloudakis, E. et al. Porphyrins and phthalocyanines as biomimetic tools for photocatalytic H2 production and CO2 reduction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 6965–7045 (2022).

O’Neill, J. S., Kearney, L., Brandon, M. P. & Pryce, M. T. Design components of porphyrin-based photocatalytic hydrogen evolution systems: a review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 467, 214599 (2022).

Pugliese, E. et al. Dissection of light-induced charge accumulation at a highly active iron porphyrin: insights in the photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202117530 (2022).

Kosugi, K., Akatsuka, C., Iwami, H., Kondo, M. & Masaoka, S. Iron-complex-based supramolecular framework catalyst for visible-light-driven CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 10451–10457 (2023).

Kuramochi, Y., Fujisawa, Y. & Satake, A. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction mediated by electron transfer via the excited triplet state of Zn(II) porphyrin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 705–709 (2019).

Huang, Q. et al. Demystifying the roles of single metal site and cluster in CO2 reduction via light and electric dual-responsive polyoxometalate-based metal-organic frameworks. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd5598 (2022).

Wu, Y., Rodríguez-López, N. & Villagrán, D. Hydrogen gas generation using a metal-free fluorinated porphyrin. Chem. Sci. 9, 4689–4695 (2018).

Gotico, P., Halime, Z. & Aukauloo, A. Recent advances in metalloporphyrin-based catalyst design towards carbon dioxide reduction: from bio-inspired second coordination sphere modifications to hierarchical architectures. Dalton Trans. 49, 2381–2396 (2020).

Zhang, J.-X., Hu, C.-Y., Wang, W., Wang, H. & Bian, Z.-Y. Visible light driven reduction of CO2 catalyzed by an abundant manganese catalyst with zinc porphyrin photosensitizer. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 522, 145–151 (2016).

Lan, G. et al. Biomimetic active sites on monolayered metal-organic frameworks for artificial photosynthesis. Nat. Catal. 5, 1006–1018 (2022).

Zou, L., Sa, R., Lv, H., Zhong, H. & Wang, R. Recent advances on metalloporphyrin-based materials for visible-light-driven CO2 reduction. ChemSusChem 13, 6124–6140 (2020).

Lu, M. et al. Rational design of crystalline covalent organic frameworks for efficient CO2 photoreduction with H2O. Angew. Chem. 131, 12522–12527 (2019).

Isayama, T. et al. An accessory chromophore in red vision. Nature 443, 649 (2006).

Taniguchi, M. & Lindsey, J. S. Synthetic chlorins, possible surrogates for chlorophylls, prepared by derivatization of porphyrins. Chem. Rev. 117, 344–535 (2016).

Lindsey, J. S. De novo synthesis of gem-dialkyl chlorophyll analogues for probing and emulating our green world. Chem. Rev. 115, 6534–6620 (2015).

Taniguchi, M., Ptaszek, M., McDowell, B. E., Boyle, P. D. & Lindsey, J. S. Sparsely substituted chlorins as core constructs in chlorophyll analogue chemistry. Part 3: Spectral and structural properties. Tetrahedron 63, 3850–3863 (2007).

Manke, A.-M., Geisel, K., Fetzer, A. & Kurz, P. A water-soluble tin(iv) porphyrin as a bioinspired photosensitiser for light-driven proton-reduction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 12029–12042 (2014).

Wilson, G. S. & Peychal-Heiling, G. Electrochemical studies of tetraphenylporphin, tetraphenylchlorin, and tetraphenylbacteriochlorin. Anal. Chem. 43, 550–556 (1971).

Inhoffen, H. H., Jäger, P. & Mählhop, R. Zur weiteren kenntnis des chlorophylls und des hämins, XXXII. Partialsynthese von rhodin-g7-trimethylester aus chlorin-e6-trimethylester, zugleich vollendung der harvard-synthese des chlorophylls a zum chlorophyll b. Justus Liebigs Ann. der Chem. 749, 109–116 (1971).

Wilson, G. S. & Peychal-Heiling, G. Electrochemical studies of some porphyrin IX derivatives in aprotic media. Anal. Chem. 43, 545–550 (1971).

Inhoffen, H. H. Recent progress in chlorophyll and porphyrin chemistry. Pure Appl. Chem. 17, 443–460 (1968).

Inhoffen, H. H., Jäger, P., Mählhop, R. & Mengler, C.-D. Zur weiteren kenntnis des chlorophylls und des hämins, XII. Elektrochernische weduktionen an porphyrinen und chlorinen, IV. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 704, 188–207 (1967).

Liu, X. et al. A Mo2-ZnP molecular device that mimics photosystem I for solar-chemical energy conversion. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 286, 119836 (2021).

Salzl, S., Ertl, M. & Knör, G. Evidence for photosensitised hydrogen production from water in the absence of precious metals, redox-mediators and co-catalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 8141–8147 (2017).

Oppelt, K. T. et al. Photocatalytic reduction of artificial and natural nucleotide co-factors with a chlorophyll-like tin-dihydroporphyrin sensitizer. Inorg. Chem. 52, 11910–11922 (2013).

Sun, R. et al. Proton-coupled electron transfer of macrocyclic ring hydrogenation: the chlorinphlorin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2122063119 (2022).

Babu, B., Sindelo, A., Mack, J. & Nyokong, T. Thien-2-yl substituted chlorins as photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy and photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy. Dyes Pigments 185, 108886 (2021).

Lu, K. et al. Chlorin-based nanoscale metal–organic framework systemically rejects colorectal cancers via synergistic photodynamic therapy and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12502–12510 (2016).

Laville, I. et al. Synthesis, cellular internalization and photodynamic activity of glucoconjugated derivatives of tri and tetra(meta-hydroxyphenyl)chlorins. Biorg. Med. Chem. 11, 1643–1652 (2003).

Maher, A. G. et al. Hydrogen evolution catalysis by a sparsely substituted cobalt chlorin. ACS Catal. 7, 3597–3606 (2017).

Lei, Q. et al. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction with aminoanthraquinone organic dyes. Nat. Commun. 14, 1087 (2023).

Yuan, H., Cheng, B., Lei, J., Jiang, L. & Han, Z. Promoting photocatalytic CO2 reduction with a molecular copper purpurin chromophore. Nat. Commun. 12, 1835 (2021).

Rao, H., Schmidt, L. C., Bonin, J. & Robert, M. Visible-light-driven methane formation from CO2 with a molecular iron catalyst. Nature 548, 74–77 (2017).

Costentin, C., Passard, G., Robert, M. & Savéant, J.-M. Pendant acid–base groups in molecular catalysts: H-Bond promoters or proton relays? Mechanisms of the conversion of CO2 to CO by electrogenerated iron(0)porphyrins bearing prepositioned phenol functionalities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11821–11829 (2014).

Costentin, C., Drouet, S., Robert, M. & Savéant, J.-M. A local proton source enhances CO2 electroreduction to CO by a molecular Fe catalyst. Science 338, 90–94 (2012).

Samankumara, L. P., Zeller, M., Krause, J. A. & Brückner, C. Syntheses, structures, modification, and optical properties of meso-tetraaryl-2,3-dimethoxychlorin, and two isomeric meso-tetraaryl-2,3,12,13-tetrahydroxybacteriochlorins. Org. Biomol. Chem. 8, 1951 (2010).

Chaudhri, N., Brückner, C. & Zeller, M. Crystal structure of cis-7,8-dihydroxy-5,10,15,20-tetraphenylchlorin and its zinc(II)–ethylenediamine complex. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallographic Commun. 78, 392–398 (2022).

Tamaki, Y., Koike, K., Morimoto, T. & Ishitani, O. Substantial improvement in the efficiency and durability of a photocatalyst for carbon dioxide reduction using a benzoimidazole derivative as an electron donor. J. Catal. 304, 22–28 (2013).

Hasegawa, E. et al. Photoinduced electron-transfer systems consisting of electron-donating pyrenes or anthracenes and benzimidazolines for reductive transformation of carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron 62, 6581–6588 (2006).

Guo, Z. et al. Highly efficient and selective photocatalytic CO2 reduction by iron and cobalt quaterpyridine complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9413–9416 (2016).

Nakajima, T. et al. Photocatalytic reduction of low concentration of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13818–13821 (2016).

Bonin, J., Chaussemier, M., Robert, M. & Routier, M. Homogeneous photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO using iron(0) porphyrin catalysts: mechanism and intrinsic limitations. ChemCatChem 6, 3200–3207 (2014).

Bonin, J., Maurin, A. & Robert, M. Molecular catalysis of the electrochemical and photochemical reduction of CO2 with Fe and Co metal based complexes. Recent advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 334, 184–198 (2017).

Rao, H., Bonin, J. & Robert, M. Non-sensitized selective photochemical reduction of CO2 to CO under visible light with an iron molecular catalyst. Chem. Commun. 53, 2830–2833 (2017).

Ding, Y., Gao, Y. & Li, Z. Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) and Co(dmgH)2PyCl synergistically promote photocatalytic hydrogen evolution over hexagonal ZnIn2S4. Appl. Surf. Sci. 462, 255–262 (2018).

Hu, Y. et al. Tracking mechanistic pathway of photocatalytic CO2 reaction at Ni sites using operando, time-resolved spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5618–5626 (2020).

Cao, H. et al. Far-red light-induced reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer polymerization using a man-made bacteriochlorin. ACS Macro Lett. 8, 616–622 (2019).

Tomkowicz, Z. et al. Slow magnetic relaxations in manganese(III) tetra(meta-fluorophenyl)porphyrin-tetracyanoethenide. Comparison with the relative single chain magnet ortho compound. Inorg. Chem. 51, 9983–9994 (2012).

Zhang, Z. & Gevorgyan, V. Co-catalyzed transannulation of pyridotriazoles with isothiocyanates and xanthate esters. Org. Lett. 22, 8500–8504 (2020).

de Souza, M. C. et al. From porphyrin benzylphosphoramidate conjugates to the catalytic hydrogenation of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)porphyrin. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 10, 628–633 (2014).

Wu, M., Liu, Z. & Zhang, W. An ultra-stable bio-inspired bacteriochlorin analogue for hypoxia-tolerant photodynamic therapy. Chem. Sci. 12, 1295–1301 (2021).

Sheldrick, G. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 64, 112–122 (2008).

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 339–341 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support provided by Sun Yat-sen University, GBRCE for Functional Molecular Engineering, and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022TQ0380 H.Y.; 2022M723586 H.Y.). We thank Z. Yang for providing instrumental support for fluorescence measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H. conceived the research. Z.H. and S.Y. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S.Y. performed synthesis of chromophores, light-driven, and UV–vis experiments. H.Y. synthesized FeTDHPP and performed DLS tests. K.G. and L.J. collected and analyzed the crystallographic data. S.Y., Z.W., and M.M. performed electrochemical measurements. J.Y. assisted in photolysis experiments using F4TPP. All authors analyzed data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Yuan, H., Guo, K. et al. Fluorinated chlorin chromophores for red-light-driven CO2 reduction. Nat Commun 15, 5704 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50084-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50084-8