Abstract

Cross-linked polymers with covalent adaptable networks (CANs) can be reprocessed under external stimuli owing to the exchangeability of dynamic covalent bonds. Optimization of reprocessing conditions is critical since increasing the reprocessing temperature costs more energy and even deteriorates the materials, while reducing the reprocessing temperature via molecular design usually narrows the service temperature range. Exploiting CO2 gas as an external trigger for lowering the reprocessing barrier shows great promise in low sample contamination and environmental friendliness. Herein, we develop a type of CANs incorporated with ionic clusters that achieve CO2-facilitated recyclability without sacrificing performance. The presence of CO2 can facilitate the rearrangement of ionic clusters, thus promoting the exchange of dynamic bonds. The effective stress relaxation and network rearrangement enable the system with rapid recycling under CO2 while retaining excellent mechanical performance in working conditions. This work opens avenues to design recyclable polymer materials with tunable dynamics and responsive recyclability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Covalent adaptable networks (CANs) employ dynamic covalent bonds in cross-linked polymer systems, in which the exchange of dynamic bonds between cross-links proceeds under mild conditions or is driven by appropriate external stimuli (mostly heating)1,2. Upon activation of bond exchange, the systems undergo topological changes and stress relaxation. Such bond exchange process can be classified into two mechanisms, i.e., dissociative and associative processes3. Many associative exchange chemistries have been widely explored, including transesterifications4,5, transimination6,7, boronic esters exchange8,9,10, thiol exchange11, silyl ether exchange12, vinylogous urethane exchange13,14, olefins metathesis reactions15,16, etc. The CANs with associative (and even some dissociative) chemistries exhibit Arrhenius-like temperature dependence of viscosity, and such materials are also termed as “vitrimer”17,18. Owing to these attractive dynamic features, CANs are promising recyclable materials even with extreme toughness, self-healing properties, and shape memory functionality19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27.

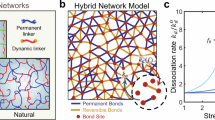

To achieve desired properties such as improved thermal recyclability, many strategies have been explored to impart new functionalities to the CANs systems. In principle, these strategies can be divided into permanent and temporary types depending on the reversibility of new functionalities. The permanent strategy includes control of polymer architecture28,29, modification on the adjacent groups30, and incorporation of other types of cross-links31,32. The imparted functionalities are persistent with the systems no matter of working or reprocessing conditions. For example, our group reported that the highly improved mechanical properties and thermal recyclability were acquired through the defined network design of the CANs33; another work was designed to achieve the tunability of dynamic and recyclability by varying adjacent groups34. However, the permanent strategy suffers from the trade-off relationship between service performance and reprocessing condition: increasing the service temperature will elevate the reprocessing temperature (or time), requiring higher energy and even deteriorating the intrinsic chemical structure during thermal recycling. Obviously, designing molecular structures with reduced reprocessing time (or temperature) will narrow the service temperature range and may even affect the mechanical robustness at working conditions.

On the other hand, the temporary strategy allows reversible functionalities of CANs by applying or removing an external trigger such as pH, light, and magnet35,36,37, which is preferred for addressing such a trade-off. Namely, these CANs exhibit high physical performance under serving conditions while allowing low reprocessing temperature/time by applying the specific trigger. However, the above-mentioned external triggers have limitations. For example, the pH stimulus can only be designed in solvent/water systems like organogel and hydrogel rather than in bulk polymer networks38. The light stimulus needs to be applied to certain materials under specific conditions, as some materials are placed in an opaque container. The CANs with magnetic response generally require high energy consumption and long processing time in the recycling procedure due to the stable covalent network structure39.

Gas, being easy to be “on” and “off” benefiting industrial large-scale operations, represents a promising external stimulus for tuning the physical properties of CAN systems. Among various gases, CO2 shows some unique advantages including being abundant, inexpensive, nontoxic, non-flammable, and no sample contamination. The functional groups, such as amine, amidine, guanidine, or imidazole, can react with carbonic acid generated by CO2 in the presence of water or wet organic solvents40,41,42,43,44. With such a principle, CO2 stimulation has been widely used in various solution or hydrogel systems, including drug delivery, self-assemblies, and switchable surfaces45,46,47. Recently, CO2 was also employed in tuning the mechanical properties of a bulk elastomer by softening its ionic aggregates48. However, to the best of our knowledge, the principle of utilizing CO2 stimulation has not been explored to tune the dynamic properties of bulk CAN systems for facilitating recyclability.

Herein, we report a covalent adaptable network incorporated with ionic clusters (IC-CAN) for CO2-facilitated recycling without impairing their service performance. By cross-linking the modified branched poly(ethyleneimine) with acetoacetoxyethyl-based copolymer, the double cross-linked network containing vinylogous urethane dynamic covalent and ionic cluster cross-links was constructed. The dynamic covalent and non-covalent exchange chemistries were employed for thermal recycling and gas response, respectively, which also possess synergistic bond exchange. The optimized IC-CAN exhibits high flexibility, good gas permeability, and rapid recyclability in a CO2 environment. Given the easy availability and removability of CO2 gas, we envision that such IC-CAN with CO2-tunable dynamics offers intriguing opportunities for designing gas-sensitive polymers applied in smart and/or sustainable materials with well-tunable properties.

Results

Material design

The covalent adaptable network incorporated with ionic clusters (IC-CAN) was synthesized by reacting neutralized carboxylic acid-modified branched poly(ethyleneimine) (NCA-PEI) ionomer with statistical copolymers of poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate and 2-acetoacetoxyethyl methacrylate (PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA). Synthetic procedures of the two precursors are detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1. The cross-linking process of the NCA-PEI with PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA is driven by combining the dynamic covalent interactions, i.e., vinylogous urethane bonds, and the ionic interactions between the carboxylate and amine groups, as shown in Fig. 1. With strong electrostatic interactions among –NH3+, –COO−, and N+(CH3)4 (shortly named M+) in matrix with a relatively low dielectric constant, ions have a strong tendency to pair or form larger aggregates49. The sufficiently dense aggregates with restricted molecule mobility surrounding would overlap and form clusters50. The amine organo-bases also interact with CO2, which readily affects the ionic interactions. The ionic clusters with increased ion mobility became looser and larger when being exposed to CO2, compared with those in the air. Such an interruption process promotes segmental mobility, thus accelerating the dynamic process and topological rearrangement of the cross-linking networks.

To investigate the structure effect on CAN performance, several control groups were synthesized via tuning ionic interactions and dynamic covalent cross-links (Supplementary Fig. 2). The pure CAN without ionic groups was labeled as control-A. The control-B without neutralization of the carboxy groups was also synthesized, where the ionic cross-links were solely contributed by –NH3+ and -COO- (without M+). The higher content of vinylogous urethane-based crosslinks in control-C was obtained as compared with that of the IC-CAN due to the higher feed ratio of AAEMA, and the samples with varied cross-linking density is shown in Supplementary Table 1. In general, the proposed network design principle can be applied to many other polymer systems (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane, polystyrene, and polyester-based) for desired applications, and the rigid polymers with low chain mobility might require harsh processing conditions for efficient bond relaxation.

The chemical structures, bond formation, molecular weight, thermal properties, and solvent resistance of the synthesized products were confirmed by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR, Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Supplementary Fig. 5), gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Supplementary Fig. 6), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Supplementary Fig. 7), and solvent soaking observation (Supplementary Fig. 8), respectively. The IC-CAN, showing higher conductivity than the control-A from the broadband dielectric spectroscopy (BDS) result (Supplementary Fig. 9), confirms the strong ionic interactions within the networks. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves of the IC-CAN and control-A are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. Compared with the single glass transition temperatures (Tg) around −50.0 °C for the control-A, the IC-CAN demonstrated two Tgs at −51.6 °C and −13.7 °C, respectively. The ionic clusters usually possess a separate Tg because of the surrounding restricted mobility50. Since the Tgs of PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA and NCA-PEI are −60.8 °C and −17.8 °C (Supplementary Fig. 11), respectively, the additional Tg can be attributed to the microphase-separated ionic clusters28. This is consistent with the reported ionic aggregates in the ionomers that have a locally higher Tg than the polymer matrix51.

CO2 responsiveness

To investigate the CO2 sensitivity with the system, the pure gas permeability and ideal selectivity of IC-CAN and control membranes were measured using pure CO2 or N2 at 2 atm and 35 °C. As shown in Fig. 2a, the IC-CAN exhibits the highest CO2 permeability (141.1 Barrer) and CO2/N2 selectivity (24.6) among the synthesized CANs. Specifically, the CO2 permeability of IC-CAN with multiple ions (–NH3+, –COO−, and M+) is higher than control-B (–NH3+ and –COO−) and significantly higher than control-A (only –NH3+). This can be explained by higher CO2 solubility in the ionic clusters (larger scale CO2-philic stickers) of IC-CAN in comparison with the control-A/B systems. On the other hand, the increased contents of dynamic covalent bonds, i.e., control-C, which increases chemical cross-links and interrupts the ionic clusters, results in a decrement in CO2 permeability.

a Gas permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity of different CANs. b SAXS profiles of the IC-CAN measured with air or CO2 purging. c SAXS profiles of the control-A measured with air or CO2 purging. d AFM mappings of the IC-CAN (upper panel) and control-A (bottom panel). e Aggregates from MD simulations after coalescence and surrounding gas molecules for 1000 ns within 1 nm. f RDF referenced to the center of mass (COM) of the aggregates. g The contact number of two aggregates in the initial structure as a function of time.

To analyze the mechanism behind the CO2 responsiveness of IC-CAN, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) was utilized for probing material structures. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, the SAXS profile of IC-CAN in air displays a broad peak at q ~ 0.031 Å−1, while no such peak is visible in the pattern of the control-A that was cross-linked by only dynamic covalent bonds. Hence, the peak at ~0.031 Å−1 is a clear indication of microphase separation in the IC-CAN that can be attributed to scattering from the ionic clusters52. The SAXS plots were fitted based on the Yarusso-Cooper model to obtain the size of the clusters53:

where the R1 (radius of the ionic core) and RCA (radius of the ionic core plus the hydrocarbon shell) of IC-CAN were calculated to be 3.2 nm and 8.7 nm, respectively. When the samples were purged with CO2 gas, the SAXS peaks of the IC-CAN with CO2-sensitive moieties shifted to lower q ~ 0.025 Å−1, indicating the increased cluster size (R1 ~ 6.3 nm and RCA ~ 10.4 nm). Meanwhile, the intensity of the peak, which was defined by the number of clusters and the difference in scattering length density between associating groups and backbones52, increased as compared with that tested in air. Such variation of IC-CAN in air and CO2 conditions indicates that the ionic clusters change through CO2-triggered rearrangement of ionic groups. On the other hand, no peak observed in the SAXS pattern of control-A even after CO2 purging, further evidence of the influence of CO2 on the system through interacting with the ionic clusters (Fig. 2c). The microphase separation behavior illustrated by SAXS results of IC-CAN and control-A were further confirmed by atomic force microscopy (AFM, Fig. 2d). The IC-CAN shows some separated microphases with higher modulus, and the distance between each microphase region matches with the SAXS calculation. Relatively smooth morphology is observed for control-A (without ionic clusters). In addition, there is a broad peak at q ~ 0.046 Å−1 in the control-B profile, while the insignificant peak is observed for control-C profile due to the increased density of dynamic covalent cross-links (Supplementary Fig. 12). The results are consistent with the gas permeability and DSC results (two Tgs in control-B and one Tg in control-C, Supplementary Fig. 13). The two Tgs of control-B are −50.1 °C (polymer matrix) and 39.3 °C (ionic clusters), in which Tg corresponding to ionic clusters is higher than that in IC-CAN due to the stronger ionic interactions between –COO− and –NH3+ than those among –COO−, –NH3+, and M+.

There are two types of mechanisms reported for the rearrangement of ionic clusters: ion hopping and collective rearrangement. The former refers to individual ion or ion pair hopping between relatively stationary clusters48,51,53, whereas the latter consists of (two or multiple) clusters fusing, rearranging, and breaking apart49. In-situ SAXS measurement at variable temperatures was conducted to analyze the temperature dependence of ionic clusters in IC-CAN (Supplementary Fig. 14), and no significant change in the SAXS profiles is observed with increased temperatures. The current experimental methods are unable to confirm the mechanism of our materials. Considering the confined situation of ionic clusters in IC-CAN by other covalent cross-links, we expect the ion hopping mechanism for the IC-CAN system due to the low energy barrier.

To illustrate the CO2 incentives, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on interactions between gas molecules and ionic aggregates were developed (Supplementary Fig. 15, Supplementary Table 2). Some representative repeating units of the IC-CAN were employed to mimic the macromolecules in gas environments of CO2 and N2. Figure 2e displays the aggregates after 1000 ns coalescence. The number of surrounding gas molecules is distinctly different, where the number of CO2 molecules enveloping the aggregates is significantly larger compared with the ones in N2. This finding, combined with the radial distribution function (RDF) result, suggests the significantly stronger binding capacity of CO2 than that of N2 (Fig. 2f).

The coalescence process of the aggregates was explored using the contact number. Two aggregates within the initial structures were labeled separately, and their contact numbers were continuously monitored, as revealed in Fig. 2g. A substantial increase in contact number observed in both gas cases at the initial stage is attributed to the extended simulation timescale, and the contact number increases gradually in a much finer time resolution (Supplementary Fig. 16). In CO2 environment, the contact number of the two aggregates continues to rise, while there is a plateau for the N2 case where the coalescence is slow or even static. The contact number result implies that the CO2 environment significantly enhances the coalescence of the molecules. Considering the strong binding capacity of CO2 with aggregates which facilitate aggregate coalescence, two explanations are proposed: (1) CO2 is adsorbed on the aggregate molecules and concurrently combined with multiple molecules, effectively increasing the meeting opportunities between different molecules and thus facilitating the coalescence among molecules. (2) CO2 is adsorbed onto the aggregate molecules, and the compact and active CO2 molecules continue to agitate the aggregate molecules, thereby fastening the dynamics of aggregate molecules.

Network dynamics

The dynamic mechanical properties of the as-prepared IC-CAN were characterized by dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), and the storage modulus (E′), loss modulus (E′′), and damping factor (tan δ) as a function of temperature for the IC-CAN from −50 °C to 100 °C measured in N2 are shown in Fig. 3a. E′ decreases from 800 MPa to 0.2 MPa due to the α-relaxation process, as the tan δ curve indicates a typical peak in the Tg range. The Tg estimated from the peak maximum in tan δ is ~−15 °C, higher than that revealed by DSC (−51.6 °C), which is commonly seen between these two methods of thermal analysis54. The same experiments were performed in the CO2 environment as shown in Fig. 3b. Comparison of the tan δ curves measured in CO2 and N2 shows similar behavior with comparable Tg values (Supplementary Fig. 17). However, the E′ obtained in CO2 is significantly lower than that measured in N2 (Fig. 3c), indicating the enhanced mobility of IC-CAN molecules in CO2 environment. The time-dependent relaxation modulus of CANs was characterized by the DMA stress relaxation test in both CO2 and N2 atmospheres (Fig. 3d) with the characteristic relaxation time (τ) identified as the value of 1/e 28. It can be observed that the IC-CAN displays a faster chain relaxation in CO2 condition (τ = 0.33 s) compared with that in N2 (τ = 3.67 s). The relationship between τ and CO2/N2 ratio, i.e., 100%, 50%, 25%, and 0% fractions of CO2, is shown in the inset of Fig. 3d. The τ of IC-CAN decreases in a nearly linear behavior as the CO2 fraction increases, suggesting that CO2 promotes a faster chain relaxation and more efficient stress dissipation. On the other hand, the control-A without ionic interactions shows no significant mechanical property differences between N2 and CO2 measurements (Supplementary Fig. 18). The observed decrease in E′ and faster stress relaxation for IC-CAN in CO2 confirm that the CO2 gas could disrupt the ionic bonds and facilitate the rearrangement of dynamic bonds.

a DMA temperature sweep curves of IC-CAN from −50 °C to 100 °C measured in N2. b DMA temperature sweep curves of IC-CAN from −50 °C to 100 °C measured in CO2. c Comparison of E′ for IC-CAN measured in N2 and CO2. d DMA stress relaxation curves of IC-CAN after being normalized. The inset shows the linear relationship between the relaxation time of IC-CAN and the fraction of CO2 in the CO2/N2 mixture.

To gain an insight into the viscoelastic property, the rheology measurement of IC-CAN and control-A was investigated. The master curves were obtained by conducting a time–temperature-superposition based on frequency sweeps at different temperatures with a reference temperature of 25 °C (Fig. 4a, b). The storage modulus (G′) of IC-CAN is higher than that of control-A over the wide frequency range, which is contributed by the additional ionic interactions. At the high-frequency range, the Tgs, defined as the peak temperatures of loss modulus (Gʺ), are determined as the corresponding frequency sweep at around −40 °C. As frequency decreases, the glass-to-rubber transition is observed with both G′ and Gʺ decreasing, and the relaxation of ionic clusters occurs at this stage51. Such transition behavior of ionic clusters did not manifest in the form of a single characteristic Gʺ peak in the master curve; instead, it merged with the chain relaxation of the polymer matrix into a broad peak. The plateau region of G′ curves at a lower frequency manifests the cross-linked structure of IC-CAN and control-A, and the cross-linking density (cx) can be calculated by the plateau value with the following equation55

The cx of the IC-CAN and control-A samples were obtained as 3.87 \(\times\) 10−5 mol/cm3 and 1.39 \(\times\) 10−5 mol/cm3, respectively, and the slightly higher cx of IC-CAN is attributed to the ionic cross-links. The dynamic modulus of control-A at high temperature (low frequency) shows the typical terminal relaxation with the crossover observed in the scans at about 125 °C, which can be related to the vinylogous urethane exchange56. However, no analogous crossover is observed up to around 300 °C for IC-CAN, which confirms that the introduction of ionic clusters improves the service temperature range. According to the TGA results, a small fraction of IC-CAN would decompose after 200 °C which may correspond to the dissociation of partial molecules from NCA-PEI, and the drastic drop of G′ and G′′ in IC-CAN after 300 °C can be interpreted as the onset of network decomposition. The comparative tan δ curves of IC-CAN and control-A in Fig. 4c also clearly manifest such a trend. These results indicate that the ionic interaction combined with CAN sustains the cross-linking of the system even at high temperatures prior to the terminal relaxation, allowing better network stability compared to control-A.

The master curve of IC-CAN tested under CO2 gas is shown in Fig. 4d, and the data below 25 °C are unable to be obtained since the CO2 gas was used to replace the liquid nitrogen/N2 gas. The G′ at the plateau region under CO2 gas is significantly lower than that under N2 gas, indicating the plasticizing effect of CO2 on the mechanical properties of IC-CAN. This can be explained that the existence of CO2 affects the equilibrium of ionic clusters by interacting with amines, which promotes the network rearrangement and results in lower cx (1.50 \(\times\) 10−5 mol/cm3). Notably, the relaxation of the vinylogous urethane exchange (high-temperature crossover) for IC-CAN in CO2 is observed in scans at a lower temperature range (~275 °C) than that in N2, suggesting the CO2-accelerated ionic cluster relaxation can facilitate the rearrangement of dynamic covalent exchange. In addition, the relationship between shear modulus and CO2 fraction in the CO2/N2 mixture was investigated, as shown in Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 19, and both G′ and G* of IC-CAN decrease gradually as the CO2 fraction increases. The results further confirm that CO2, acting as a plasticizer, can lower the energy barrier of bond exchange as well as accelerate the network rearrangement.

CO2-facilitated recyclability

The comparative tensile properties of the IC-CAN and control samples were measured to demonstrate the microstructure-mechanical performance relationships. The IC-CAN exhibits decent mechanical performance (Fig. 5a, b) with the tensile stress, Young’s modulus, elongation at break, and toughness being 0.27 MPa, 0.15 MPa, 204%, and 0.25 MJ/m3, respectively. The higher tensile stress of IC-CAN compared with control-A is ascribed to the additional ionic cross-links that possess rapid reformation ability. A reported material system with ionic clusters also supports the point that the ionic aggregates are acting as “strong” cross-links and exhibit high fracture stress51. The higher tensile stress (1.59 MPa) and brittleness of control-B, as compared with those of the IC-CAN, are possibly due to the stronger ionic interactions (higher Tg corresponding to the ionic clusters as confirmed by DSC) among more dispersive ionic cross-links (smaller ionic clusters evidenced by SAXS). With the increased dynamic covalent cross-links, the tensile stress (0.65 MPa) and brittleness of the control-C also slightly increased. However, the increased dynamic covalent cross-links would restrict the chain mobility and thus weaken the CO2 sensitivity, leading to a longer reprocessing time for mechanical recycling (Supplementary Fig. 20). Hence, the IC-CAN with decent cross-links and excellent CO2 permeability was used for the recyclability test.

a Stress–strain curves of the synthesized CANs. b Tensile properties of the synthesized CANs. c Photographs of the IC-CAN recycling. d Stress–strain curves of the pristine and recycled IC-CAN samples with different reprocessing times in N2. e Stress–strain curves of the pristine and recycled IC-CAN samples with different reprocessing times in CO2 at 100 °C under a pressure of 0.05 MPa. f Recyclable efficiency of the IC-CAN in CO2 and N2 at 100 °C under a pressure of 0.05 MPa.

The IC-CAN and control films were cut into small pieces, followed by compression molding at 100 °C (Fig. 5c). As verified by the gas permeation test mentioned above, it is feasible that CO2 can significantly permeate the IC-CAN film. The small pieces were reprocessed into integrated and coherent films, which is ascribed to the critical contribution of the dynamic covalent bonding and ionic interactions. The pristine and reprocessed films were subjected to uniaxial tensile tests to quantify the mechanical recovery with different processing hours (Fig. 5d). After being pressed in N2 for 24 h, the recycled IC-CAN samples exhibited comparable mechanical strength (0.28 MPa) and elongation at break (200%) with the pristine ones. The recycling experiments of the IC-CAN were similarly performed in CO2, and its mechanical properties were fully recovered within 8 h, as shown in Fig. 5e. In addition to reprocessing time, the variation of temperatures and pressures were also investigated (see Supplementary Fig. 21 and Supplementary Table 3), and the results show that the mechanical properties of the recycled IC-CAN can also be fully recovered in CO2 atmosphere at lower temperatures (80 °C), lower pressure (0.025 MPa), and even less time (1 h at 120 °C under 5 MPa). Since the rapid dynamic bond exchange offers faster recycling properties48, the rapid mechanical recovery of IC-CAN films in a CO2 environment (Fig. 5f ) confirms that CO2 gas accelerated the ionic bond reformation. The presence of CO2 weakens the ionic interactions, increasing ionic cluster size as demonstrated above, which softens the dynamic network and achieves faster network rearrangement at elevated temperatures. Furthermore, the FT-IR result shows no visible chemical degradation after recycling (Supplementary Fig. 22). Hence, the IC-CAN exhibits excellent gas-sensitive recycling properties without loss of mechanical properties or chemical changes, providing an avenue for the design of responsive or recyclable CANs.

Overall, even with advancements in special CO2-facilitated recyclability, there is a trade-off between mechanical properties and gas responsiveness for the network design. Increasing the dynamic covalent cross-links can effectively enhance mechanical strength while restricting chain mobility and hence reducing CO2 sensitivity. However, there should be some solutions to surpass this trade-off for those applications where high strength is preferentially required. For example, an increase of the ionic cross-links between molecular chains rather than dynamic covalent cross-links should be able to enhance both mechanical strength and CO2-responsiveness. In addition, alteration of backbone chains, dynamic covalent bonds, and ionic groups, as well as control of the degree of entanglement, number of cross-links, etc., can be implemented in the network design for property optimization. A few cases are tentatively verified to demonstrate the feasibility of simultaneous enhancement of mechanical strength and CO2 responsiveness by the above-mentioned solutions (Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Figs. 23 and 24). For example, the modified PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA with tertiary amine units and sulfonate groups was prepared to improve the ionic interactions between PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA and NCA-PEI in the IC-CAN system (see structure in Supplementary Fig. 23a). As compared with those of the original IC-CAN, its tensile strength and toughness can be increased by 600% and 250%, respectively, without sacrificing the CO2 permeability.

Discussion

In this study, a CAN with CO2-facilitated recyclability is first reported through a rational structure design with the combination of both dynamic covalent bonds and gas-sensitive ionic interactions. The effect of network structure on CAN performance was comprehensively investigated with the designed control samples, and the gas permeability test confirmed the optimal CO2-responsiveness of IC-CAN samples with proper dynamic covalent cross-linking and ionic clusters. From SAXS data, we managed to infer that the CO2 interacted with the CAN system by softening and enlarging the ionic clusters, and such interactions were further confirmed by molecular dynamics simulations. The DMA, rheology, and tensile tests demonstrated shorter relaxation time, higher flexibility, and more rapid reprocessing for the IC-CAN in a CO2 environment than those in an N2 atmosphere. The combined experimental characterization and simulations manifested that CO2 gas can be used as a stimulus to facilitate dynamic bond exchange by weakening the ionic interactions, enabling faster network rearrangement. At normal operating conditions, the two interactions, i.e., dynamic covalent bonds and ionic interactions, are in equilibrium. When CO2 is purged into the system, the interactions between CO2 and amine groups weaken the ionic interactions between carboxylate and amines, disrupting the existing ionic clusters in the networks. During the reformation of ionic clusters, the free amine groups then could have the chance to form new dynamic covalent bonds with the acetoacetate group, therefore the dynamic bond rearrangement could be accelerated by the CO2 gas. Within the system incorporated with ionic clusters that is loosened upon CO2 exposure, the CO2-facilitated bond exchange and topological rearrangement then render the system for faster stress relaxation and lower reprocessing barrier without sacrificing the performance.

In such a CAN system, the dynamic covalent bonding contributes to the recyclability while the ionic interactions are responsive for interacting with CO2 gas. The proposed approach will be applied to other CAN systems based on different polymer backbones, types of ionic clusters, or dynamic covalent bonds, and will be explored to flourish such the new research area of gas-facilitated recyclability. Since applying and removing CO2 is a simple process with nominal energy consumption, it is expected that such design offers an alternative approach to surpass the trade-off between service performance and reprocessing conditions. Combined with other benefits including but not limited to natural abundancy, high safety, no sample contamination, insensitivity to environmental variation (vs. moisture as a trigger), and applicability to non-transparent conditions (vs. light as a trigger), such strategy is highly promising for a variety of industrial applications.

Methods

Materials

Poly(ethyleneimine) solution (PEI, Mn ~ 1800 g/mol, 50 wt% in H2O), succinic anhydride, tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAOH, 25 wt% in H2O), azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate (PEGMEMA, Mn ~300), 2-acetoacetoxyethyl methacrylate (AAEMA), as well as all organic solvents (HPLC grade) including dimethyl formamide (DMF), methanol, ethanol, chloroform, diethyl ether, tetrahydrofuran (THF), dichloromethane, toluene, acetone, hexane, and ethyl acetate were purchased from Millipore Sigma. The inhibitors in the monomer were removed by passing through a column packed with inhibitor remover (Millipore Sigma).

Synthesis of NCA-PEI

The NCA-PEI was prepared via carboxylation of PEI and partial neutralization of the carboxy groups using TMAOH. Based on the 13C-NMR spectra of PEI (Supplementary Fig. 25), the ratio of primary, secondary, and tertiary amine of the PEI was calculated to be 39: 38:34 for designing the carboxylation ratio of PEI57. 1.0 equiv. PEI was added into DMF/H2O (v/v = 1/1), and 8 equiv. succinic anhydride was then slowly added into the PEI solution and stirred overnight under an N2 atmosphere. Half of the primary amine should be carboxylated. Afterwards, 8 equiv. TMAOH was added to the solution and stirred for another 1 h. The solvents were removed by a rotary evaporator, and the remaining viscous liquid was dried under vacuum overnight. For the control-A without neutralization of the carboxy groups, TMAOH was not used in this step.

By comparing the FT-IR spectra between the PEI and NCA-PEI, the amide group (C = O) formation in the NCA-PEI was confirmed at 1647 cm−1, and a band at 1572 cm−1 was assigned for the C = O group from the neutralized carboxylate. The formation of the quaternary amine group in the NCA-PEI was verified by the FT-IR spectra at 950 cm−1 and the 1H-NMR spectra with \(\delta\) (ppm) = 3.19. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta\) (ppm) = 2.03 (s, 2H), \(\delta\) = 2.17 (s, 2H), \(\delta\) = 3.06 (t, 2H).

Synthesis of PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA

PEGMEMA (0.9 equiv.), 2-acetoacetoxyethyl methacrylate (0.1 equiv.), and AIBN (0.01 equiv.) were added to a 250 mL flask containing THF solvent (25 wt% solute in THF). The solution was purged with N2 for 30 min and then stirred at 65 °C overnight. The reaction was cooled down and concentrated by rotary evaporation. The viscous liquid was precipitated in diethyl ether and dried under vacuum.

In the FT-IR spectrum of the PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA, a band at 1725 cm−1 and a band at 1100 cm−1 indicate the stretching vibration of C = O and C-O-C groups of the PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA, respectively. The molecular weight (Mn) and PDI of the PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA were estimated by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) to be ~35,000 and 2.35, respectively. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): \(\delta\) (ppm) = 2.32 (s, 3H), \(\delta\) = 4.09 (s, 2H), \(\delta\) = 4.17 (s, 2H), \(\delta\) = 4.36 (s, 2H).

Preparation of IC-CAN

In total, 0.75 g NCA-PEI, 1.5 g PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA, 17.5 ml THF, and 17.5 ml methanol were added into a 40 ml vial and mixed under vigorous shaking for 10 min until the polymers were completely dissolved. The mixture was then poured into a Teflon petri dish and dried at 80 °C for 4 hours to form a cast film with dual cross-linking. The control-A, by reacting pure PEI and PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA, was prepared under the same conditions. The comparison of FT-IR spectra of the IC-CAN and control-A confirms the presence of a quaternary amine group (950 cm−1) in the IC-CAN. The control-B was prepared by reacting the carboxylated PEI and PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA under the same conditions, and the control-C was prepared by reacting the NCA-PEI and modified PEGMEMA-co-PAAEMA (0.9 equiv. PEGMEMA and 0.3 equiv. AAEMA) under the same conditions.

Preparation of recycled IC-CAN

The recyclable samples were cut into small pieces and then placed in an oven under a N2 or CO2 atmosphere for 1 h. The reprocessing was normally conducted at 100 °C under a controlled pressure of 0.05 MPa for 24 h if conditions were not specifically stated.

Characterization

1H-NMR measurement: 1H-NMR spectra were measured on an NMR spectrometer (400 MHz, Avance III, Bruker). The samples were dissolved in DMSO-d6 containing tetramethylsilane as an internal standard.

Cross-linking density measurement: The cross-linking density of the CANs was measured using the low-field NMR cross-linking density instrument from Suzhou Niumag Corporation.

GPC measurement: GPC was performed in THF using an HLC-8320GPC (TOSOH) system. THF was used as the eluent at 40 °C. The column set was calibrated using standard polystyrene samples with small polydispersity indices.

FT-IR spectroscopy: FT-IR spectra were recorded on an FT-IR spectrometer (Nicolet iS50, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Measurements were performed in transmittance mode.

DSC measurement: Tg was evaluated by a DSC system (DSC2500, TA Instruments). The samples were heated from −80 °C to 120 °C with a ramp rate of 5 °C/min under N2.

TGA measurement: TGA measurement was conducted on a TGA instrument (Q-50, TA Instruments) with a ramp rate of 10 °C/min from room temperature to 600 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere.

DMA measurement: DMA experiments were performed in tensile mode on a DMA instrument (TA Discovery DMA850) under a nitrogen or CO2 atmosphere. The rectangular-shaped samples were heated from −50 °C to 100 °C with a ramp rate of 3.0 °C/min at a frequency of 1 Hz. The stress relaxation test was performed at 1 Hz and 0 °C with a strain of 5%. The Tg was taken as the peak of tan δ.

Tensile test: The tensile stress–strain curves of the samples were obtained using a universal tester (Instron 3343 Universal Testing System). The measurement followed the ASTM D1708 standard at a test speed of 1 mm/s.

Rheological measurement: Small amplitude oscillatory shear measurements were conducted from 60 to −50 °C utilizing an 8 mm diameter parallel plate on a rheometer (AR2000ex, TA Instruments) that was mounted with an ETC environmental chamber and used liquid nitrogen as the cooling source. For each temperature, the frequency sweep was conducted in a range of 102 rad/s to 10−1 rad/s, and the strain was chosen based on the strain sweep at 1 Hz to ensure linear viscoelasticity.

BDS measurement: BDS measurements were conducted on a Concept-80 system (Novocontrol GmbH) that was connected with an Alpha-A impedance analyzer and utilized a temperature controller (Quatro Cryosystem). The temperature range was set from 173 to 373 K with a stability of ±0.1 K. The complex dielectric permittivity was measured in a frequency range of 10−1 to 106 Hz using a fixed AC volt of 0.1 V between two gold-coated disk-shaped electrodes with a diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 0.2 mm.

Gas permeation test: The gas permeation test was performed on a self-developed gas permeation cell based on a constant volume variable pressure testing method58 using N2 and CO2 as feed gas at 35 °C with an upstream pressure of 2 atm. The samples were cut into a circle with an effective permeation area of 1.13 cm2 and a thickness of 0.8 mm. Before measurement, the gas permeation cell was vacuumed overnight to remove absorbed gases from the sample. During the test, the upstream was pressurized, and the downstream was sealed. The increment in the downstream pressure over time was recorded by a computer. A curve of pressure vs. time was generated and the slope of the curve was used to calculate gas permeability using Eq. (6):

where P was the gas permeability in Barrer [1 Barrer = 1 × 10−10 cm3 (STP) cm/cm2 s cmHg], V (cm3) was the volume of the downstream chamber, A (cm2) the effective membrane area for gas transport, l (cm) the thickness of membrane, T (K) the test temperature, P2 (psia) the upstream pressure, and dp1/dt was ratio of downstream pressure vs. time.

The ideal selectivity was calculated by Eq. (7):

where αA/B was ideal selectivity, PA the fast-permeated gas, and PB was the slow-permeated gas.

SAXS measurement: The SAXS measurement was conducted on an SAXS instrument (Xeuss 3.0, Xenocs) equipped with Cu and Mo as radiation sources at 50 kV and 0.6 mA under a dry air or CO2 atmosphere, which generated an incident X-ray beam with the wavelength of λGa = 0.154189 nm and beam area of 1.2 mm × 1.2 mm. The sample-to-detector distance was calibrated as 0.9 m. For the variable temperature measurement, each temperature was static for 10 min before the test.

AFM measurement: The AFM mapping measurements were operated on a Bruker Dimension® Icon™ atomic force microscope using PeakForce Quantitative Nanomechanical Mapping mode at ambient conditions.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the main manuscript and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Denissen, W., Winne, J. M. & Du Prez, F. E. Vitrimers: permanent organic networks with glass-like fluidity. Chem. Sci. 7, 30–38 (2016).

Capelot, M., Unterlass, M. M., Tournilhac, F. & Leibler, L. Catalytic control of the vitrimer glass transition. ACS Macro Lett. 1, 789–792 (2012).

Li, B., Cao, P. F., Saito, T. & Sokolov, A. P. Intrinsically self-healing polymers: from mechanistic insight to current challenges. Chem. Rev. 123, 701–735 (2023).

Brutman, J. P., Delgado, P. A. & Hillmyer, M. A. Polylactide vitrimers. ACS Macro Lett. 3, 607–610 (2014).

Niu, X. et al. Using Zn2+ ionomer to catalyze transesterification reaction in epoxy vitrimer. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 5698–5706 (2019).

Taynton, P. et al. Heat- or water-driven malleability in a highly recyclable covalent network polymer. Adv. Mater. 26, 3938–3942 (2014).

Chao, A., Negulescu, I. & Zhang, D. Dynamic covalent polymer networks based on degenerative imine bond exchange: tuning the malleability and self-healing properties by solvent. Macromolecules 49, 6277–6284 (2016).

Cromwell, O. R., Chung, J. & Guan, Z. Malleable and self-healing covalent polymer networks through tunable dynamic boronic ester bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6492–6495 (2015).

Röttger, M. et al. High-performance vitrimers from commodity thermoplastics through dioxaborolane metathesis. Science 356, 62–65 (2017).

Chen, H. et al. Spiroborate-linked ionic covalent adaptable networks with rapid reprocessability and closed-loop recyclability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9112–9117 (2023).

Ishibashi, J. S. & Kalow, J. A. Vitrimeric silicone elastomers enabled by dynamic meldrum’s acid-derived cross-links. ACS Macro Lett. 7, 482–486 (2018).

Nishimura, Y., Chung, J., Muradyan, H. & Guan, Z. Silyl ether as a robust and thermally stable dynamic covalent motif for malleable polymer design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 14881–14884 (2017).

Lessard, J. J. et al. Catalyst-free vitrimers from vinyl polymers. Macromolecules 52, 2105–2111 (2019).

Denissen, W. et al. Chemical control of the viscoelastic properties of vinylogous urethane vitrimers. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–7 (2017).

Lu, Y.-X., Tournilhac, F., Leibler, L. & Guan, Z. Making insoluble polymer networks malleable via olefin metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8424–8427 (2012).

Liu, H. et al. Dynamic remodeling of covalent networks via ring-opening metathesis polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 7, 933–937 (2018).

Luo, J. et al. Elastic vitrimers: beyond thermoplastic and thermoset elastomers. Matter 5, 1391–1422 (2022).

Elling, B. R. & Dichtel, W. R. Reprocessable cross-linked polymer networks: are associative exchange mechanisms desirable? ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1488–1496 (2020).

Alabiso, W. & Schlögl, S. The impact of vitrimers on the industry of the future: chemistry, properties and sustainable forward-looking applications. Polymers 12, 1660 (2020).

Zheng, N., Fang, Z., Zou, W., Zhao, Q. & Xie, T. Thermoset shape‐memory polyurethane with intrinsic plasticity enabled by transcarbamoylation. Angew. Chem. 128, 11593–11597 (2016).

Pei, Z., Yang, Y., Chen, Q., Wei, Y. & Ji, Y. Regional shape control of strategically assembled multishape memory vitrimers. Adv. Mater. 28, 156–160 (2016).

Cash, J. J., Kubo, T., Bapat, A. P. & Sumerlin, B. S. Room-temperature self-healing polymers based on dynamic-covalent boronic esters. Macromolecules 48, 2098–2106 (2015).

Zou, Z. et al. Rehealable, fully recyclable, and malleable electronic skin enabled by dynamic covalent thermoset nanocomposite. Sci. Adv. 4, eaaq0508 (2018).

Tran, H., Feig, V. R., Liu, K., Zheng, Y. & Bao, Z. Polymer chemistries underpinning materials for skin-inspired electronics. Macromolecules 52, 3965–3974 (2019).

Li, Y. M., Zhang, Z. P., Rong, M. Z. & Zhang, M. Q. Tailored modular assembly derived self-healing polythioureas with largely tunable properties covering plastics, elastomers and fibers. Nat. Commun. 13, 2633 (2022).

Kloxin, C. J. & Bowman, C. N. Covalent adaptable networks: smart, reconfigurable and responsive network systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 7161–7173 (2013).

Jin, Y., Lei, Z., Taynton, P., Huang, S. & Zhang, W. Malleable and recyclable thermosets: the next generation of plastics. Matter 1, 1456–1493 (2019).

Lessard, J. J. et al. Block copolymer vitrimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 283–289 (2020).

Chen, Q. et al. Exceptionally recyclable, extremely tough, vitrimer-like polydimethylsiloxane elastomers via rational network design. Matter 6, 3378–3393 (2023).

Xing, K. et al. The role of chain-end association lifetime in segmental and chain dynamics of telechelic polymers. Macromolecules 51, 8561–8573 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Strong and tough supramolecular covalent adaptable networks with room-temperature closed-loop recyclability. Adv. Mater. 35, e2208619 (2023).

Li, L., Chen, X., Jin, K. & Torkelson, J. M. Vitrimers designed both to strongly suppress creep and to recover original cross-link density after reprocessing: quantitative theory and experiments. Macromolecules 51, 5537–5546 (2018).

Luo, J. et al. Highly recyclable and tough elastic vitrimers from a defined polydimethylsiloxane network. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310989 (2023).

Demchuk, Z. et al. Tuning the mechanical and dynamic properties of elastic vitrimers by tailoring the substituents of boronic ester. ACS Mater. Au 4, 185–194 (2023).

Kloxin, C. J., Scott, T. F., Adzima, B. J. & Bowman, C. N. Covalent adaptable networks (CANs): a unique paradigm in cross-linked polymers. Macromolecules 43, 2643–2653 (2010).

Maeda, T., Otsuka, H. & Takahara, A. Dynamic covalent polymers: reorganizable polymers with dynamic covalent bonds. Prog. Polym. Sci. 34, 581–604 (2009).

Miao, W. et al. On demand shape memory polymer via light regulated topological defects in a dynamic covalent network. Nat. Commun. 11, 4257 (2020).

Yesilyurt, V. et al. Injectable self‐healing glucose‐responsive hydrogels with pH‐regulated mechanical properties. Adv. Mater. 28, 86–91 (2016).

Liang, H., Wei, Y. & Ji, Y. Magnetic-responsive covalent adaptable networks. Chem. Asian J. 18, e202201177 (2023).

Fan, W., Tong, X., Farnia, F., Yu, B. & Zhao, Y. CO2-responsive polymer single-chain nanoparticles and self-assembly for gas-tunable nanoreactors. Chem. Mater. 29, 5693–5701 (2017).

Zhang, H., Wu, W., Zhao, X. & Zhao, Y. Synthesis and thermoresponsive behaviors of thermo-, pH-, CO2-, and oxidation-responsive linear and cyclic graft copolymers. Macromolecules 50, 3411–3423 (2017).

Han, B. & Wu, T. Green Chemistry and Chemical Engineering (Springer, New York, 2019).

Quek, J. Y., Roth, P. J., Evans, R. A., Davis, T. P. & Lowe, A. B. Reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer synthesis of amidine‐based, CO2‐responsive homo and AB diblock (Co) polymers comprised of histamine and their gas‐triggered self‐assembly in water. J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Chem. 51, 394–404 (2013).

Yan, Q. et al. CO2‐responsive polymeric vesicles that breathe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 4923–4927 (2011).

Liu, H., Lin, S., Feng, Y. & Theato, P. CO 2-Responsive polymer materials. Polym. Chem. 8, 12–23 (2017).

Zhang, Q., Lei, L. & Zhu, S. Gas-responsive polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 6, 515–522 (2017).

Abbasi, R., Mitchell, A., Jessop, P. G. & Cunningham, M. F. Crosslinking CO2-switchable polymers for paints and coatings applications. RSC Appl. Polym. 2, 214–223 (2024).

Miwa, Y., Taira, K., Kurachi, J., Udagawa, T. & Kutsumizu, S. A gas-plastic elastomer that quickly self-heals damage with the aid of CO2 gas. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–6 (2019).

Hall, L. M., Stevens, M. J. & Frischknecht, A. L. Dynamics of model Ionomer melts of various architectures. Macromolecules 45, 8097–8108 (2012).

Kim, S.-H. & Kim, J.-S. Effects of low matrix glass transition temperature on the cluster formation of Ionomers having two Ion pairs per ionic repeat unit. Macromolecules 36, 1870–1875 (2003).

Miwa, Y., Kurachi, J., Kohbara, Y. & Kutsumizu, S. Dynamic ionic crosslinks enable high strength and ultrastretchability in a single elastomer. Commun. Chem. 1, 5 (2018).

Ge, S. et al. Critical role of the interfacial layer in associating polymers with microphase separation. Macromolecules 54, 4246–4256 (2021).

Miwa, Y., Kurachi, J., Sugino, Y., Udagawa, T. & Kutsumizu, S. Toward strong self-healing polyisoprene elastomers with dynamic ionic crosslinks. Soft Matter 16, 3384–3394 (2020).

Startsev, O. V., Vapirov, Y. M., Lebedev, M. P. & Kychkin, A. K. Comparison of glass-transition temperatures for epoxy polymers obtained by methods of thermal analysis. Mech. Compos. Mater. 56, 227–240 (2020).

Li, B. et al. Rational polymer design of stretchable poly(ionic liquid) membranes for dual applications. Macromolecules 54, 896–905 (2020).

Denissen, W. et al. Vinylogous urethane vitrimers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 2451–2457 (2015).

Cao, X. et al. Core-shell type multiarm star poly(ε-caprolactone) with high molecular weight hyperbranched polyethylenimine as core: Synthesis, characterization and encapsulation properties. Eur. Polym. J. 44, 1060–1070 (2008).

Wang, F. et al. Sub-Tg cross-linked thermally rearranged polybenzoxazole derived from phenolphthalein diamine for natural gas purification. J. Membr. Sci. 687, 122033 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 52373275 and 52303290, received by P.-F. Cao and J. Chen, respectively). APS acknowledges support from NSF (award DMR-1904657, received by A.P. Sokolov) for data interpretation. The authors would like to thank Prof. Ming Tian and Dr. Chenchen Tian from the Beijing University of Chemical Technology, China, for the AFM characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiayao Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Funding acquisition. Lin Li: Methodology, Investigation. Jiancheng Luo: Conceptualization, Methodology. Lingyao Meng: Investigation, Writing—original draft. Xiao Zhao: Validation, Writing—review & editing. Shenghan Song: Investigation, Writing—original draft. Zoriana Demchuk: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. Pei Li: Investigation. Yi He: Validation. Alexei P. Sokolov: Data interpretation, Writing—review & editing. Peng-Fei Cao: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wei Zhang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Li, L., Luo, J. et al. Covalent adaptable polymer networks with CO2-facilitated recyclability. Nat Commun 15, 6605 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50738-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50738-7

This article is cited by

-

Entropy-driven toughening and closed-loop recycling of polymers via divergent metal-pyrazole interactions

Nature Communications (2025)

-

CO2-triggered reversible transformation of soft elastomers into rigid and highly fluorescent plastics

Nature Communications (2025)