Abstract

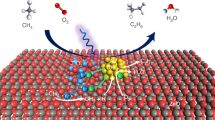

The direct co-conversion of methane and carbon dioxide into valuable chemicals has been a longstanding scientific pursuit for carbon neutrality and combating climate change. Herein, we present a photo-driven chemical process that reforms these two major greenhouse gases together to generate green methanol and CO, two high-valued industrial chemicals. Isotopic labeling and control experiments indicate an oxygen-atom-graft occurs, wherein CO2 transfers one O into the C–H bond of CH4 via photo-activated interfacial catalysis with AuPd nanoparticles supported on GaN. The photoexcited AuPd/GaN interface effectively orchestrates the CH4 oxidation and the CO2 reduction producing 13.66 mmol g−1 of CH3OH yield over 10 h. This design provides a solid scientific basis for the photo-driven oxygen-atom-grafting process to be further extended to visible light region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global warming due to excess greenhouse emissions is sparking unprecedented attention worldwide. CO2 and CH4, accounting for over 90% of total global emissions in 2021, have been deemed as primary anthropogenic greenhouse gases1. Concurrently, both gases, characterized by high-bond energy, have been recognized as C1 feedstocks for bulk chemicals and fuel productions, aligning with the vision of achieving net-zero emission (Fig. 1a)2,3. In recent years, significant strides have been made in reducing CO24,5,6,7 with H2 or H2O as hydrogen sources, as well as oxidizing CH48,9,10 with O2, H2O, or H2O2 into high-valued products and fuels independently (Fig. 1b, c). However, a redox-neutral direct co-reforming of these greenhouse gases into valuable chemicals remains both an intricate scientific challenge and highly desirable. The merits of this proposed negative emission method include not having to use oxidants and reductants, thereby minimizing the risk of undesired side reactions such as overoxidation or over-hydrogenation. Toward this objective, while dry reforming technology11,12,13 and direct co-conversions14,15,16 undoubtedly offer a promising reaction model for the synthesis of syngas or acetic acid, the dry reforming process primarily generates syngas, which requires subsequent chemical transformations such as the Fischer–Tropsch (FT) process into valued chemicals (Fig. 1d). Moreover, even with cutting-edge dry reforming technology, significant challenges persist in identifying coke-resistant materials that can maintain optimal performance over the long term for syngas synthesis. The same issues are also encountered in the co-conversions of CH4 and CO2 for direct synthesis of acetic acid.

a The challenges in attaining a net-zero-carbon footprint. Previously established pathways of converting b CO2 and c CH4, facilitated by separate reduction and oxidation processes. d Co-conversion process of CO2 and CH4 for the production of valuable chemicals. e This work presents an oxygen-atom-graft process from CO2 to CH4 via photo-interfacial catalysis.

The escalating global energy demands are driving the speedy advancement of the novel energy industry. With the increasing maturity of CH3OH-related energy storage and release technologies (i.e., fuel cells and combustion engines), green CH3OH has become an important liquid energy storage and transportation carrier, thanks to its high energy density (726 kJ mol−1)17,18. The growing demand for CH3OH provides an unprecedented opportunity to explore more sustainable and atom-efficient methodologies19,20. Conceptually, a much more appealing approach involves the co-conversion of CH4 and CO2 directly into CH3OH without the input of other chemicals. However, making this approach a powerful tool for producing CH3OH, it is imperative to break an unfavorable uphill energy barrier with high reaction temperature. Such harsh conditions would exacerbate side reactions and coking. In this context, photocatalytic systems, especially heterogeneous photoactive surfaces where photoexcited electron-hole pairs function as active sites, are potentially powerful platforms for co-converting CO2 and CH4. However, despite tremendous advances achieved in light-driven CH4 reforming conversion with CO2, most research remains extensively focused on syngas formation. Furthermore, a co-conversion approach may be facilitated by interfacial photocatalysts comprising metals and semiconductors, ranging from early ZrO2/MgO/Ga2O3, TiO2, and C3N4 to recently developed LaNiO321,22,23,24,25. Unfortunately, few reports associated with targeting photosynthesis of CH3OH have been presented so far, mainly due to the intrinsic difficulties in pre-absorbing and subsequently activating both CH4 and CO226. We hypothesized that the key to overcoming such a challenge is to identify a heterogeneous photocatalyst that can activate CH4 and CO2 on its surface, and simultaneously break the C–H and C=O bonds under mild conditions. This process would form CH3OH upon their recombination, resulting in the graft of an oxygen atom from CO2 to CH4.

Since the first example of GaN-enabled CH4 photoconversion in 2014, our research group has been exploring the C–H functionalization catalyzed by the GaN surface. The studied systems have involved the deposition of a range of cocatalysts, namely Pd, Cu, Pt, and RhOx, facilitating the production of chemicals such as toluene, benzene, and cyclohexane27,28,29. In these well-examined cases, GaN typically serves two roles: (1) acting as a photosensitive solid ligand to activate the metal co-catalyst; and (2) directly initiating C–H bond cleavage on the photoexcited surface. In addition, it is well documented that CO2 can also be polarized and undergo extensive photo-reductive conversions on GaN powder or nanowires30,31. We postulated that combining metal nanoparticles as cocatalysts with GaN as photo-promotor would forge an efficient metal/GaN interface that will enable direct CH3OH photosynthesis from CH4 and CO2. Herein, we report the direct and highly selective synthesis of CH3OH from CH4 and CO2 under light illumination. The CH3OH productivity achieved in this study reaches up to 1405 μmol g−1 h−1, thus overperforming existing co-reformings of CH4 and CO2 for syngas synthesis reported in the literature by a factor of 3.8.

Results

To commence our study, we carried out the photocatalytic reaction using various heterogeneous photo-catalysts in a handcrafted chamber illuminated by full-spectrum light (Fig. 2 and Table S1). The control experiments revealed that the combination of CH4 and CO2 at room temperature did not yield any detectable CH3OH in the absence of light or catalysts. Utilizing commercial GaN powder as a catalyst led to a higher methanol rate of 41 μmol g−1 h−1 than other semiconductors traditionally used for photo-CH4 dehydrogenation and CO2 reduction. This finding underscores GaN’s exceptional potential for efficient photocatalytic conversion of CH4 and CO2 into CH3OH.

To further boost the reaction efficiency, air-stable single-metal particles, including Ir, Ru, Pt, Rh, Pd, and Au, were in situ deposited on the GaN support via a universal chemical-reduction method (Fig. S1), forming an active interface denoted as metal/GaN-cr. Among these, monometallic interfaces featuring Au and Pd nanoparticles provided a notable increase in photocatalytic activity. In the field of both traditional thermal and sustainable-energy-driven reactions, bimetallic nanoparticles can remarkably augment catalytic performance in terms of conversion and selectivity, a phenomenon described as a 1 + 1 > 2 synthetic effect32,33. Motivated by this encouraging principle to improve reactivity, we experimented with 0.2 wt% metal loading of both physical mixture of Au with Pd and their alloy in varying weight ratios under standard conditions. Further, increasing metal loading to 0.5 wt% and even 1 wt% did not increase the CH3OH yield (Table S2). Thus, 0.2 wt% loading of alloyed AuPd/GaN interface with a 1-to-1 weight ratio eventually offers us the best CH3OH production rate among all tested samples.

With this AuPd/GaN-cr catalyst in hand, we first characterized the nano-sized distribution of metal particles. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of AuPd/GaN-cr demonstrate a suboptimal metal dispersion in bulky GaN support, a consequence of the in situ chemical reduction preparation (Figs. S2 and S3). To improve this apparent drawback of metal aggregation, we employed a soft colloid-immobilization process. This method enabled the assembly of the AuPd alloy with GaN, resulting in evenly distributed metal nanoparticles coupled with intact and highly active GaN (denoted as AuPd/GaN-ci)—as opposed to the etching by base or acid (Fig. 3a). As can be seen from a typical high-angle annular dark field-scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image and its size population analysis of AuPd/GaN-ci (Figs. 3b–e and S4), the average diameter of 3.59 nm of metal colloid particles has been evenly immobilized on the GaN surface. The well-established bimetallic composition of supported AuPd alloy was also confirmed by the following energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy analysis. More importantly, despite successive load-wash-dry catalyst processing treatments, the composition and crystalline structure of the GaN host remained largely unchanged, as reflected by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) results (Fig. S5). This implies the great prospect of GaN powder as active support in photocatalysis industrial settings. The TEM and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) results clearly illustrate the well-dispersion and formation of active metal/GaN interface, respectively (Fig. 3f, g). In addition, the enhanced UV–vis photo-adsorption property (Fig. S6) in UV and visible range of AuPd/GaN-ci might arise from interband absorption and plasmonic effect on metallic AuPd nanoparticles’ surface, which was further confirmed in the results of Au 4f and Pd 3d X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Fig. S7).

Taking such an interfacial AuPd/GaN-ci as the best-in-class photocatalyst, we proceeded to evaluate its photocatalytic redox behavior relative to AuPd/GaN-cr under initial reaction conditions shown in Fig. 2. Notably, the CH3OH production rate over AuPd/GaN-ci can increase to a high value that is 2.6 times greater than that attained by AuPd/GaN-cr (Fig. 4a and Table S3). Detailed analysis further confirmed that CH3OH and CO are the predominant products in oxygenates and gas phases, respectively (Fig. S8 and Table S4). The distinctive disparity in reactivity between AuPd/GaN-ci and bare GaN, especially in CH3OH production estimated to be 34 times higher, affirms the critical role of AuPd/GaN interface in the photocatalytic co-conversion of CH4 with CO2 to CH3OH (Fig. 4b). Such inference is further consolidated by a giant leap in CH3OH yield from unsupported AuPd particles to AuPd/GaN-ci (Fig. 4b and Table S5). These findings inspired us to embark on trials with additional interfacial catalysts comprising alloy AuPd and various representative semiconductors. However, it did not lead to further enhancement of CH3OH yield, despite the wide-band structures of Ga2O3, ZnO, and TiO2 being known for direct methane activation (Fig. 4c and Table S6). These results suggest that the interfacial AuPd/GaN surface possesses a unique catalytic efficacy in converting CH4 and CO2 into CH3OH.

a Methanol and CO yield rates over Au/GaN-ci, AuPd/GaN-ci, and Pd/GaN-ci under standard conditions. b The importance of AuPd/GaN-ci interface in photoconversion of CH4 and CO2. c The effect of different wide-band semiconductors on reactivity. d The methanol production of AuPd/GaN-ci under different ratios of CH4 and CO2 gas mixture, and e different pressures. f Performance comparison of AuPd/GaN-ci with the reported photocatalytic systems in the literature. (The references are listed in the Table S9) Standard reaction conditions: 2.5 mmol of CH4, 2.5 mmol of CO2, 1 mg of catalyst, full-spectrum Xenon lamp, 2 h.

Considering the intrinsic nature of this novel redox transformation, involving CH4 and CO2 simultaneously, we investigated the impact of varying CH4/CO2 ratio on CH3OH production while maintaining total gas pressure of 1 bar (Fig. 4d and Table S7). Our data analysis revealed that an increase in the proportion of either CH4 or CO2 resulted in lower CH3OH yield and selectivity, demonstrating that a 1:1 ratio of CH4/CO2 is most favorable for our designed photocatalytic system. Moreover, when submitting this photoconversion to low pressure of 0.2 atm, it still achieved a CH3OH productivity of 435 μmol g−1 h−1, a rate that aligns with the record reported in prior studies for CH3OH (Fig. 4e and Table S8). More importantly, the yield rate of 1405 μmol g−1 h−1 obtained under ambient pressure exceeded those of other conventional photocatalytic syngas-based dry-reforming systems (Fig. 4f and Table S9). However, such active AuPd/GaN surface begins to give a reduced CH3OH yield after extensive reuse (Table S10), likely due to either unavoidable oxidation of metal cocatalyst with O species from CO2 (Figs. S9 and S10) or slow aggregation of metal (Fig. S11). In spite of this, the robustness and applicability of the photocatalytic system toward CH3OH production under batch reactor was demonstrated by reusing over 10 h with a total CH3OH yield of 13.66 mmol g−1 and a turnover number (TON) of 941, with no noticeable carbon depositions (Table S10 and Fig. S12).

With such an improved CH3OH productivity, we move forward to understand the reaction mechanism under light-driven conditions, which appears to be very different from the well-known process of dry-reforming of CH4 and CO2. Overwhelming research on CH3OH synthesis finds that CO2, CO, and CH4 can each serve as the carbon source, reacting with appropriate reductants or oxidants2,34. In our analysis of gas products, CO was almost the exclusive product with negligible amounts of H2 and other hydrocarbons (Figs. S13 and S14 and Table S4). This observation effectively eliminates the significant impact of CH4 dehydrogenation as a side reaction35. Given the previous indirect pathway from CH4 (CO2) to CH3OH via intermediates (H2, CO, O2) (Fig. 5a inset and Table S11), we examined the reactivity of AuPd/GaN-ci in control experiments wherein identical ratios of H2 + CO2, H2 + CO, and CH4 + CO as reactants were used. As depicted in Fig. 5a, the control systems all showed much lower CH3OH yield. These experiments ruled out the potential pathway in which CO2 or CO, acting as the main carbon source, reacts with H2 – which could be possibly generated from CH4—to form CH3OH. Furthermore, replacing CH4 + CO2 with CH4 + O2 in a 10:1 ratio, where the number of oxygen atoms exceeds those theoretically generated from CO2 to CO (quantified as 6.6 μmol), did not prompt CH4 conversion to CH3OH. The result ruled out the CH4-oxidation with O2, possibly derived in situ from CO2 cleavage, as the primary mechanism for CH3OH production. On all accounts, it is induced that this unique photocatalytic CH3OH synthesis is mostly likely to undergo a direct transformation of CH4 and CO2 through surface catalysis rather than an indirect route mediated by intermediate such as CO, O2, or H2.

a Generation rates of methanol from photoconversion of 2.5 mmol H2 + 2.5 mmol CO2, 2.5 mmol H2 + 2.5 mmol CO, 2.5 mmol CH4 + 2.5 mmol CO, and 2.5 mmol CH4 + 0.25 mmol O2 over AuPd/GaN-ci. b GC–MS spectra of CO produced from photoconversion of 12CH4 + 12C16O2 and 12CH4 + 13C16O2. c GC–MS spectra of CH3OH produced from photoconversion of 12CH4 + 12C16O2, 13CH4 + 12C16O2, and 12CH4 + 12C18O2. d Kinetic isotope effects for photoconversion of CH4 with CO2. e The generation rate of methanol from CH4 photoconversion with CO2 over AuPd/GaN-ci under photo-driven and thermal catalytic conditions. The inset of e shows the Arrhenius plot of methanol photosynthesis over AuPd/GaN-ci.

In the next study, the 13C-labeled experiment was implemented to further ascertain the carbon source of products, sketching the specific functions of the two gases in the overall reaction. When using 13CO2 instead of 12CO2, the characteristic peak of CO at m/z = 28 shifted up to m/z = 29 (Fig. 5b). In conjunction with the reductive control experiment discussed earlier, it is demonstrated that the majority of formed CO comes from CO2. In the presence of 13CO2, there is no detectable 13C labeled CH3OH (m/z = 33) by either NMR or GC–MS analysis, indicating that CO2 was not the carbon source of CH3OH (Fig. S15). Conversely, in the experiment with 13CH4, 13CH3OH signals were detected by both MS and NMR, thereby confirming the incorporation of CH4 as the primary carbon source and CO2 as the oxygen source (Figs. 5c and S16). To further trace the oxygen source in the methanol product, we conducted an O18 labeling isotopic experiment, where the generation of O18 labeled CH3OH coincides with the use of O18 labeled CO2 as the reactant. This evidence directly reveals the contribution of CO2 to the oxygen in CH3OH (Fig. 5c). Complementary to this synthesis approach, the determination of a high kinetic isotope effect (KIE) value of 3.79 and 4.88 for the CH3OH formation over AuPd/GaN-ci and GaN samples reveals that the C–H cleavage in CH4 is a critical component of the rate-determining step (Figs. 5d and S17). Based on all these findings, we proposed a distinctive transformation involving oxygen-atom-grafting (OAG) from CO2 to CH4, wherein CH4 mainly contributes to the carbon for CH3OH and CO2 to the oxygen for CH3OH in the reaction products.

To understand the role of the AuPd/GaN-ci interface in the catalytic transformation, we collected and analyzed the UV-vis diffraction and Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of various samples, including GaN, Au/GaN-ci, AuPd/GaN-ci and Pd/GaN-ci (Figs. S6 and S18). As UV–vis comparative results showed, introducing mono- or bimetallic metal catalysts did not significantly improve light adsorption in pristine GaN. Furthermore, the only PL characteristic peak observed across all GaN samples with or without metal demonstrates that the photoabsorption at the metal/GaN interface mainly originates from GaN semiconductor, rather than the metal particles. This consistency in PL peaks and UV-vis results suggests a negligible contribution of light-excited electrons from the metal alloy, which might otherwise participate in the reactant’s activation36,37. On the other hand, the diminished absorption of GaN at wavelengths above 400 nm also explains the reduced reactivity under visible light conditions (Table S12). Meanwhile, thermographic photograph measurements demonstrated that this surface photocatalysis reaction occurred at 25 °C (Fig. S19). This result confirmed the absence of a concomitant photothermal effect upon light irradiation. All these analyses identify the synergy between photoexcited GaN and alloyed AuPd, forming an active photoelectron-transfer interface that potentially enables energy and electron transfer with CH4 and CO2. Such synergistic photo-active interface thus endows the OAG process with a lower activation energy (60 kJ mol−1) than GaN (72 kJ mol−1) alone (Fig. 5e inset and S20), as well as a higher apparent quantum efficiency (Table S13). Moreover, the negligible CH3OH yield under thermally driven conditions implies the AuPd/GaN-ci interface’s effectiveness in overcoming the thermodynamic challenges of traditional thermo-catalysis in OAG conversion (Fig. 5e and Table S14). The successful application of interfacial AuPd/GaN-ci in the OAG process introduces a new perspective on using photoexcited metal/semiconductor interfaces as a versatile toolbox in advancing sustainable chemical conversions.

The further experimental findings that the molar ratio of CH3OH to CO is markedly increased on the combined AuPd/GaN-ci surface compared to the single GaN surface point toward the substantial synergistic effect of the AuPd/GaN-ci surface on activating both CH4 and CO2 (Fig. 6a inset). The interaction of CH4 and CO2 with the GaN surface has been recognized to effectively activate inert molecules for conversions19,28,30. To further elucidate this synergistic effect, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were thus performed to understand preliminary interaction behaviors that are critical for catalytic processes on GaN and AuPd/GaN-ci surfaces. The analysis commenced with the optimized configurations of the two surfaces interacting with CO2. Our DFT results show that the originally linear CO2 molecule adopts a bent structure with elongated C=O bonds upon adsorption on the polar GaN surface (Fig. 6b inset). This bending is essential for CO2 activation, with the O–C–O angle notably decreasing on the synergistic AuPd/GaN-ci surface. That significant variation in adsorption mode, compared to GaN alone, likely results from the apparent steric hindrance at the metal/GaN interface, as evidenced by the nonbonding interaction between the metal and oxygen in CO2 in both the adsorption model and corresponding differential electron density diagram (Tables S15 and S16). Consequently, the AuPd/GaN-ci surface exhibits more negative adsorption energy for CO2, indicating stronger affinity and enhanced CO2 activation. As a comprehensive result of such interaction, the evident electron transfer, particularly between CO2 and both metal and GaN surfaces, implies that adsorbed CO2 on the AuPd/GaN-ci surface is more likely to dissociate and release CO upon charge transfer (Fig. S21).

a The rates of CH4 and CO2 consumption and (inset of a) produced CH3OH-to-CO mole ratio for GaN and AuPd/GaN-ci. b The calculated adsorption energies (Eads) for adsorbed CO2 and c CH4 on GaN and AuPd/GaN-ci surfaces along with the corresponding optimized stereograms. Color code: C: dark gray; N: light gray; O: red; H: light pink; Ga: green; Au: orange; Pd: purple; d the C–H bond length of CH4 adsorbed on the comparative catalysts’ surface with the differential charge density stereograms (left, inset of d) for GaN and schematic of C–H bond activation in CH4 for AuPd/GaN-ci (right, inset of d). The cyan and yellow regions in the electron density cloud diagram indicate electron loss and gain.

Based on the O18 labeling CO2 experiment discussed above, it is plausible that the remaining oxygen atom from CO2 is then positioned to potentially graft with activated CH4 on the AuPd/GaN-ci surface to form CH3OH. For the CH4 adsorption structures, CH4 preferentially locates closer to the synergistic AuPd/GaN-ci surface, resulting in lower adsorption energy for CH4 (Fig. 6c). This observation suggests a pronounced pre-adsorption characteristic of CH4 with low-polarizability over AuPd/GaN-ci. Even so, AuPd/GaN-ci surface with a considerable negative adsorption energy of CO2 reveals a higher affinity and easier activation for CO2 than CH4, which might explain the higher consumption rate of CO2 (Fig. 6a). Consistent with previous cases, our data show significant CH4 polarization on the GaN surface, evidenced by the disparity in the electron density cloud and the elongation of the C–H bond (Fig. 6d inset left and Tables S17 and S18). Importantly, the AuPd/GaN-ci surface further intensifies the polarity of the C–H bond in CH4, leading to even greater bond stretching compared to GaN alone (Fig. 6d inset right). These results support the hypothesis that the AuPd/GaN-ci surface amplifies the direct activation of CH4 compared to the single GaN surface. Considering all of the presented experimental and DFT data above, the synergistic surface of GaN with metal on AuPd/GaN-ci can facilitate strong enough interactions with both inert CH4 and CO2 at the same time. That multifunctional capability makes it possible to drive the surface-bound intermediates pathway rather than the gas phase for the oxygen-atom of CO2 grafting with CH4, leading to the formation of CH3OH and CO.

Lastly, it is well known for its enhanced visible-light absorption capabilities when noble metals are incorporated into semiconductors38,39. For this reason, we decided to explore the potential of our synthesis for broader applicability in the visible light region, conducting this OAG reaction over GaN and interfacial AuPd/GaN-ci catalyst under the irradiation of a Xenon lamp with 435 nm wavelength of cut-off filter. Notably, the UV–vis absorption results confirm AuPd/GaN-ci’s better visible-light absorption compared to GaN (Fig. S6). As anticipated, the AuPd/GaN-ci gave a reappeared methanol yield rate in the OAG process while the unmodified GaN surface did not show reactivity (Table S19). Overall, this compelling observation presents the feasibility of our approach in CH3OH photosynthesis from CH4 and CO2 across a wide solar spectrum.

In summary, we have discovered a direct and synergistic photocatalytic method for CH3OH synthesis by co-reforming two major greenhouse gases of CH4 and CO2 under mild conditions with very high selectivity. This method employs an interfacial metal/semiconductor as a photo-redox catalyst at room temperature. The photoexcited interface between AuPd nanoparticles and GaN support ensures simultaneous C–H activation of CH4 and CO2 reduction to produce methanol via an oxygen-atom-graft from CO2 to CH4. The scalability of this transformation was demonstrated in a batch reactor by recycling the catalyst multiple times. Adapting the herein OAG process to continuous flow operations, such co-conversions of CH4 and CO2 could revolutionize industrial CH3OH production, while also making a positive impact on climate change mitigation.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Gallium (III) nitride (Thermo scientific, 99.99%), chloroplatinic acid hexahydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, ACS reagent), gold (III) chloride trihydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, ACS reagent), rhodium (III) chloride hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, ACS reagent), iridium (III) chloride trihydrate (Acros organics), NaPdCl4 (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), zinc oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, nanopowder, <100 nm particle size), titanium (IV) oxide (nanopowder, ~21 nm particle size, 99.5%), gallium (III) oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.99%), methane (Air Liquide, 99.99%), carbon dioxide (Linde), 13C labeled methane (Sigma-Aldrich, 99 atom % 13C), 13C labeled carbon dioxide (Sigma-Aldrich, 99 atom % 13C) and 18O labeled carbon dioxide (Sigma-Aldrich, 97 atom % 18O).

Synthesis of different metal/GaN-cr by in situ chemical reduction

The cocatalyst precursors used include H2PtCl6·6H2O (0.531 mg), Na2PdCl4 (0.553 mg), HAuCl4·3H2O (0.400 mg), RuCl3·xH2O (0.410 mg), IrCl3 ·3H2O (0.367 mg) and RhCl3 ·3H2O (0.407 mg). For a typical preparation of 0.2 wt % metal/GaN-cr photocatalyst, 100 mg of GaN was dispersed into 25 mL of an aqueous metal solution by ultrasonication. Then the mixture was stirred for 0.5 h, followed by the dropwise addition of an aqueous NaBH4 solution (0.15 M, 38.6 µL). After another 0.5 h of stirring, the samples were filtered and washed three times with water, then dried at 100 °C under vacuum overnight.

Synthesis of monometallic and bimetallic Au(Pd)/GaN-ci by a soft colloid-immobilization process

The typical bimetallic AuPd/GaN-ci sample was synthesized by following a well-established method for metal colloid preparation40,41. In total, 200 μL of HAuCl4 ·3H2O (2.54 mM) and 277 μL of Na2PdCl4 (3.40 mM) aqueous solutions were dissolved in 25 mL of deionized water. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, 0.2 mg), with an average molecular weight of 1,300,000, was added as a stabilizer to give the desired metal-to-PVP ratio (typically set as 1:1). After 5 min of stirring, a freshly prepared 0.15 M sodium borohydride (NaBH4) solution (38.6 µL) was introduced and maintained a NaBH4-to-metal molar ratio of 5. The bimetallic AuPd colloid solution was produced after stirring for 30 min. Subsequently, 100 mg of GaN was added to immobilize these bimetallic metal nanoparticles over another 30 minutes. The as-prepared AuPd/GaN-ci catalyst was filtered, thoroughly washed with distilled water, and left to dry under vacuum at 100 °C overnight. As controlled samples, single Au/GaN-ci and Pd/GaN-ci were prepared using the same method, but with the use of 400 μL of HAuCl4 ·3H2O (2.54 mM) and 554 μL of Na2PdCl4 (3.40 mM) aqueous solution as metal precursors, respectively.

Material characterizations: The bright field transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and HAADF-STEM observations were carried out on FEI Tecnai G2 F20 S/TEM at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Powder X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD) measurements were collected on a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with a Cu-Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Å) and operated with an increment of 0.02° and a counting time of 0.24 s under the voltage of 40 kV and 40 mA. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were conducted on a Thermo ESCALAB 250 spectrometer equipped with a monochromated Al Kα radiation (hv = 1486.6 eV). The energy of the spectrometer was calibrated by C 1s peak at 284.8 eV. Ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) measurement was performed by Agilent Cary 5000 series UV–vis–NIR spectrometer. Photoluminescence (PL) measurement was performed with a 213-nm He–Cd laser (Kimmon Koha) as the excitation source.

The photocatalytic reaction of CH4 with CO2 in a quartz chamber

Firstly, 1 mg of the catalysts was evenly distributed on the bottom of a 120 mL quartz chamber reactor. To remove water and potential gases adsorbed on the catalyst surface, the reactor was degassed at 250 °C. Then, we introduced the CH4 (2.5 mmol) and CO2 (2.5 mmol) gases into the reactor at a 1-to-1 ratio, following pump-vacuum cycles three times. The reactor was placed in a double-layered beaker with a water bath and irradiated under a 300 W Xenon lamp with a PE300BF light bulb (Excelitas) for 2 h (Fig. S22). After the photocatalytic reaction, gas products were identified and quantified by GC-FID and GC-TCD analysis. Following that, 1 mL of deionized water was injected into the reactor to absorb oxygenated products. The resulting oxygenated products were then analyzed by 1H-NMR for CH3OH, CH3OOH and HCOOH, and a colorimetric method was applied for HCHO quantification.

Quantification of oxygenated products

The oxygenated products, including CH3OH, CH3OOH, and HCOOH were analyzed and quantified via a proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy spectrometer (Bruker AVIIIHD 500 MHz). Specifically, 0.4 mL of as-formed liquid that absorbed the oxygenated products was filtered and then mixed with 0.1 mL deuterium oxide containing 0.0167 μL of DMSO as an internal standard. The calibration curves for CH3OH and HCOOH were established by plotting the concentration of standard chemicals against the 1H-NMR area ratio of products to DMSO. For the quantification of HCHO, a colorimetric method was used. Here 0.3 mL of the as-formed liquid was diluted with 2 mL of deionized water. Subsequently, 0.3 mL of reagent solution was added to this diluted mixture. The final test liquid was placed in a 35 °C water bath for 1 h. The typical reagent solution was prepared by dissolving 15 g of ammonium acetate, 0.3 mL of acetic acid and 0.2 mL of pentane-2,4-dione in 100 mL of deionized water.

Gas products analysis

Quantification of CO was obtained by gas chromatograph (GC, Clarus 590) equipped with a methanizer and flame ionization detector. We used GC (Agilent 6890 N) with a thermal conductivity detector (GC-TCD) to quantify the H2 amount. Then we used GC (Agilent 6890 N) with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) to identify and quantify hydrocarbon products (ethane).

Density function theory experiment

The photocatalytic reaction mechanism of CH4 and CO2 on controlled GaN and AuPd/GaN samples was investigated using the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP)42,43. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerh of generalized gradient approximation functional was employed for the exchange-correlation potential44. The projected augmented wave potential was applied to describe the ion–electron interaction45. A k-mesh of 5 × 3 × 1 was adopted to the primitive cell of GaN (100)-wurtzite configured as a 2 × 2 supercell. The van der Waals dispersion forces were considered using the zero damping DFT-D3 method of Grimme46. The cutoff energy for the plane-wave basis was set to be 520 eV. The AuPd/GaN-ci catalyst’s simulation involves a metal cluster of three atoms placed on a GaN surface, with the Au to Pd ratio closely reflecting the trend observed in the EDX spectrum result (Fig. 3c). The structure was optimized until the forces on each ion were smaller than 0.01 eV Å−1, and the convergence criterion for the energy was 1.0 × 10−6 eV. The adsorption energies of the substrate molecule adsorbed on the surface were determined using the following equation: Eads = EGaN-X − (EGaN + EX), where EX, EGaN, and EGaN-X represent the total energies of adsorbate X, GaN, and adsorbate X absorbed on the GaN, respectively.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data that support the findings of this study are included within this article and the Supplementary Information. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Ritchie, H., Rosado, P. & Roser, M. CO2 and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. OurWorldInData.org. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions (2023).

Li, X., Wang, C. & Tang, J. Methane transformation by photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 617–632 (2022).

Chang, X., Wang, T. & Gong, J. CO2 photo-reduction: insights into CO2 activation and reaction on surfaces of photocatalysts. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 2177 (2016).

Liu, C. et al. Gallium nitride catalyzed the direct hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to dimethyl ether as primary product. Nat. Commun. 12, 2305 (2021).

Shi, X. et al. Highly selective photocatalytic CO2 methanation with water vapor on single-atom platinum-decorated defective carbon nitride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203063 (2022).

Lin, Q. et al. Highly selective photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CH4 on electron‐rich Fe species cocatalyst under visible light irradiation. Carbon Energy 6, e435 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. Surface Ru-H bipyridine complexes-grafted TiO2 nanohybrids for efficient photocatalytic CO2 methanation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5769–5777 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Efficient hole abstraction for highly selective oxidative coupling of methane by Au-sputtered TiO2 photocatalysts. Nat. Energy 8, 1013–1022 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Visible-light-driven non-oxidative dehydrogenation of alkanes at ambient conditions. Nat. Energy 7, 1042–1051 (2022). Non-oxidative conversion of methane due to its atom-economic characteristics has recently been the hot subject of intensive studies.

Wang, G. et al. Fabrication of stepped CeO2 nanoislands for efficient photocatalytic methane coupling. ACS Catal. 13, 11666–11674 (2023).

Lang, J. Experimentelle beiträge zur kenntnis der vorgänge bei der wasser-und heizgasbereitung. Z. Phys. Chem. (Leipz.) 2, 161 (1888).

Davis, S. J. et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 360, eaas9793 (2018).

Song, Y. et al. Dry reforming of methane by stable Ni-Mo nanocatalysts on single-crystalline MgO. Science 367, 777–781 (2020).

Shavi, R. et al. Mechanistic insight into the quantitative synthesis of acetic acid by direct conversion of CH4 and CO2: an experimental and theoretical approach. Appl. Catal., B 229, 237–248 (2018).

Tu, C. et al. Insight into acetic acid synthesis from the reaction of CH4 and CO2. ACS Catal. 11, 3384–3401 (2021).

Fang, F. & Sun, X. Water radiocatalysis for selective aqueous-phase methane carboxylation with carbon dioxide into acetic acid at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 8492–8499 (2024).

Mondal, U. & Yadav, G. D. Methanol economy and net zero emissions: critical analysis of catalytic processes, reactors and technologies. Green. Chem. 23, 8361 (2021).

Olah, G. A. Beyond oil and gas: the methanol economy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 2636–2639 (2005).

Han, J.-T. et al. In aqua dual selective photocatalytic conversion of methane to formic acid and methanol with oxygen and water as oxidants without overoxidation. iScience 26, 105942 (2023).

Shinde, G. Y., Mote, A. S. & Gawande, M. B. Recent advances of photocatalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Catalysts 12, 94 (2022).

Kohno, Y., Tsunehiro, T., Takuzo, F. & Satohiro, Y. Photoreduction of carbon dioxide with methane over ZrO2. Chem. Lett. 10, 993–994 (1997).

Teramura, K. et al. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO in the presence of H2 or CH4 as a reductant over MgO. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 346–354 (2004).

László, B. et al. Photo-induced reactions in the CO2-methane system on titanate nanotubes modified with Au and Rh nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B 199, 473–484 (2016).

Tahir, B., Tahir, M. & Amin, N. A. S. Silver loaded protonated graphitic carbon nitride (Ag/pg-C3N4) nanosheets for stimulating CO2 reduction to fuels via photocatalytic bi-reforming of methane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 493, 18–31 (2019).

Yao, Y. et al. Highly efficient solar-driven dry reforming of methane on a Rh/LaNiO3 catalyst through a light-induced metal-to-metal charge transfer process. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303654 (2023).

Pino, L. et al. Kinetic study of the methane dry (CO2) reforming reaction over the Ce0.70La0.20Ni0.10O2−δ catalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 10, 2652 (2020).

Tan, L. et al. Selective conversion of methane to cyclohexane and hydrogen via efficient hydrogen transfer catalyzed by GaN supported platinum clusters. Sci. Rep. 12, 18414 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Thermal non-oxidative aromatization of light alkanes catalyzed by gallium nitride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 14106–14109 (2014).

Liu, M. et al. Photocatalytic methylation of non-activated sp3 and sp2 C-H bonds using methanol on GaN. ACS Catal. 10, 6248–6253 (2020).

AlOtaibi, B. et al. Wafer-level artificial photosynthesis for CO2 reduction into CH4 and CO using GaN nanowires. ACS Catal. 5, 5342–5348 (2015).

AlOtaibi, B. et al. Photochemical carbon dioxide reduction on Mg-Doped Ga(In)N nanowire arrays under visible light irradiation. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 246–252 (2016).

Xu, D. et al. Design of the synergistic rectifying interfaces in Mott-Schottky catalysts. Chem. Rev. 123, 1–30 (2023).

Sankar, M. et al. Designing bimetallic catalysts for a green and sustainable future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 8099–8139, (2012).

Zhou, W. et al. New horizon in C1 chemistry: breaking the selectivity limitation in transformation of syngas and hydrogenation of CO2 into hydrocarbon chemicals and fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 3193 (2019).

Meng, L. et al. Gold plasmon-induced photocatalytic dehydrogenative coupling of methane to ethane on polar oxide surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 294 (2018).

Linic, S., Aslam, U., Boerigter, C. & Morabito, M. Photochemical transformations on plasmonic metal nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 14, 567–576 (2015).

Sarina, S. et al. Viable photocatalysts under solar-spectrum irradiation: nonplasmonic metal nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2935–2940 (2014).

Li, X., Yu, J., Jaroniec, M. & Chen, X. Cocatalysts for selective photoreduction of CO2 into solar fuels. Chem. Rev. 119, 3962–4179 (2019).

Dong, W. J. & Mi, Z. One-dimensional III-nitrides: towards ultrahigh efficiency, ultrahigh stability artificial photosynthesis. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 5427 (2023).

Agarwal, N. et al. Aqueous Au-Pd colloids catalyze selective CH4 oxidation to CH3OH with O2 under mild conditions. Science 358, 223–227 (2017).

Huang, X. et al. Au-Pd separation enhances bimetallic catalysis of alcohol oxidation. Nature 603, 271–275 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Research Chair program, Fonds de Recherche du Québec Nature et technologies, the Canada Foundation for Innovations, and McGill University’s MSSI fund (to C.-J. L.). This work was also supported by the grant obtained with the assistance of Axelys and sponsored by Catalum Technologies. H. S. thanks Shanghai Jiao Tong University for a Postdoctoral Scholarship. We also acknowledge Durbis J. Castillo-Pazos for reviewing and proofreading the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-J. L., H. S., and J.-T. H. proposed the research idea. C.-J. L. supervised the project. H. S. designed this study and analyzed the data. J.-T. H. prepared the catalyst and performed catalytic measurements. J.-T. H. and H. S. characterized samples. M. S. quantified the CO gas by GC-FID. B. M. conducted density functional theory calculations. H. S. wrote the paper, and J.-T. H. C.-J. L. revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhong-Wen Liu, Masahiro Miyauchi and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, H., Han, JT., Miao, B. et al. Photosynthesis of CH3OH via oxygen-atom-grafting from CO2 to CH4 enabled by AuPd/GaN. Nat Commun 15, 6435 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50801-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50801-3