Abstract

Conjugated polymers are promising candidates for molecular wires in nanoelectronics, with flexibility in mechanics, stability in chemistry and variety in electrical conductivity. Polyene, as a segment of polyacetylene, is a typical conjugated polymer with straightforward structure and wide-range adjustable conductance. To obtain atomic scale understanding of charge transfer in polyene, we have measured the conductance of a single polyene-based molecular chain via lifting it up with scanning tunneling microscopy tip. Different from semiconducting characters in pristine polyene (polyacetylene), high conductance and low decay constant are obtained, along with an electronic state around Fermi level and characteristic vibrational mode. These observed phenomena result from pinned molecular orbital owing to molecule-electrode coupling at the interface, and weakened bond length alternation due to electron-phonon coupling inside single molecular chain. Our findings emphasize the interfacial characteristics in molecular junctions and promising properties of polyene, with single molecular conductance as a vital tool for bringing insights into the design and construction of nanodevices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecular wires play a vital role in nanoelectronics, particularly in single-molecule circuitry, where they facilitate electronic communication between different functional elements1,2. The key criteria for an optimal molecular wire include efficient charge transport, high chemical stability, and substantial conformational flexibility to accommodate diverse contact geometries. Conjugated polymers exhibit great promise as molecular wires due to their adjustable conductance and conformational flexibility. These polymers possess a “box” of mobile π-electrons derived from unsaturated building blocks, enabling macromolecules to act as electrophoresis agents for the transportation or storage of charges in field-effect transistors (FETs) and secondary batteries3,4. Consequently, it is of utmost importance to thoroughly investigate and comprehend the mechanisms of charge transport through individual conjugated polymer chains, to establish correlations between their specific chemical structures and associated electronic properties5.

Polyene, a prototype polymer in conjugated polymers, is composed of CH units arranged in a quasi-one-dimensional lattice6. In its pure trans-(CH)n form, a dimerization Peierls distortion lowers the energy of the system, forming a semiconductor. However, doping can effectively modulate the conductivity of trans-polyene, covering a range of 15 orders from insulating to metallic states7,8. On the other hand, the dimerization in trans-polyene also builds up the simplest one-dimensional model of strongly correlated topological matter, the Su–Schrieffer–Heeger (SSH) model, which produce the topological edge state9,10. The simplicity of the trans-polyene structure, the ability to control conductivity over a wide range, and the fascinating topological characters make it a platform for investigating the charge-transport process.

To find the key factors influencing the electroconductivity in single trans-polyene chain, it is essential to perform molecular-level characterization of their structure and electronic states. Recent advancements in surface polymerization combined with scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) have enabled the visualization of synthesis processes and conductance detection of various oligomers11,12,13,14 and nanoribbons15,16,17,18. Wang and co-workers fabricated both cis- and trans- polyene structures by depositing acetylene on Cu(110) surface19. Also, Li et al. reported the transformation of n-alkane into all-trans conjugated polyene via cascade dehydrogenation20. Due to the charge transfer between polyene and the copper surface, polyene chains become highly electron-doped, exhibiting metallic properties that differ significantly from pristine polyene. As a result of strong interaction between polyene and copper surfaces and multiple products during surface reactions (cis-isomer formation, and cyclization), obtaining the accurate conductance of a pure trans-polyene chain is challenging. In this work, based on previous work of our group20, we chose phenyl-modified polyene (known as diphenyl [36] conjugated polyene, labeled as 2 in Fig. 1a) to enhance \(\pi\)-tip interaction for lifting single molecule off the surface. This enables us to perform all bias-dependent conductance measurements in a single lifting-up procedure utilizing reciprocating movement. Furthermore, by focusing solely on 2 as the target molecule, we significantly reduce the diversity in chain lengths and structures in the subsequent lifting-up measurements.

a A schematic illustration of the chemical transformation involved in the study. Octadecyl benzene undergo a cascade dehydrogenation process on Cu(110) at 400 K, forming phenyl [18] conjugated polyene (1). The trans-intercoupling of 1 at 473 K yields diphenyl [36] conjugated polyene (2). b An overview STM image of molecular chains of 2 formed on Cu(110) surface. The inset displays the zoom-in STM image of a single molecular chain, accompanied by its corresponding chemical structure. The orange arrow points to the Moiré pattern in single molecule of 2. The set point parameters for the overview and zoomed-in STM images are as follows: 100 mV, 20 pA, and −200 mV, 100 pA, respectively. Scale bars are 9 nm, and 1 nm, respectively. c–e Schematic diagrams illustrate the process of lifting up a single molecule. c (e) The approach process after choosing one molecular chain (the retract process after establishing electronic contact). d The resulting current as a function of tip height during both approach (black curve) and retraction (red curve) process. Both current values reach the up limit of the preamplifier, 10 nA, with a bias voltage of 200 mV. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Results

Surface synthesis and lifting-up process

Figure 1a illustrates the synthetic pathway of the target molecular chain 2. Molecules of 2 were formed on Cu(110) via a cascade dehydrogenation of octadecyl benzene, followed by the intermolecular-coupling. The introducing of phenyl groups effectively reduces the activation energy for breaking CH bond, facilitating the dehydrogenation of octadecyl benzene at 400 K over Cu(110) (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Notes 1). Further annealing at 473 K resulted in the trans-intercoupling of phenyl [18] conjugated polyene (1), leading to the all-trans polyene structure in 2. These products are depicted as elongated dumbbell shapes with 5.4 nm in length in the inset of Fig. 1b. A Moiré pattern is observed due to the lattice mismatch between trans-polyene and the Cu substrate. For an individual molecule of 2, the polyene segment prefers to adsorbed on Cu chains along \([1\bar{1}0]\), with half of the phenyl groups aligning with the polyene trend (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). This low-coordinated configuration enhances the possibilities for vertical manipulation of a single molecule 2 with STM tip in subsequent lifting-up procedures.

To measure the single molecular conductance, we began by lifting up a molecule of 2. In the first step, after selecting an isolated chain based on a STM image, the STM tip was initially positioned at the phenyl moiety of 2 (the upper panel of Fig. 1c). Subsequently, the STM feedback loop was disabled. The tip apex was gently brought close to the selected chain until electronic contact was established, and then gradually retracted to lift it upward (the lower panel of Fig. 1c). Throughout the procedure, the variation of current with respect to vertical distance was recorded, as shown by the black and red curves in the middle panel of Fig. 1c. Both curves exhibit exponential decay (\(I={I}_{0}{{\rm{e}}}^{-\beta z}\), in which \(\beta\) is decay constant), but with distinct line shapes and decay constants. When the tip approaches, the decay constant of I(z) curve is 2.17 ± 014 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\). Based on the model of electrons tunneling through a one-dimensional potential barrier, it gives \(\beta=\frac{2\sqrt{2m\varPhi }}{\hslash }=1.02\sqrt{{\varPhi} ({\rm{eV}})}{\text{\AA}}^{-1}\), with \({\varPhi }\) represents the work function. We deduced work function of Cu(110) is approximately 4.45 eV, which closely matches the previously reported value of 4.5 eV reported in ref. 21. However, during the lifting of the molecular chain, a much smaller decay constant is observed, accompanied by oscillations.

Conductance measurements based on reciprocating motions

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the constructed surface-2-tip junction, we performed voltage-dependent conductance measurements (Fig. 2a). Previously, Grill and coworkers have done similar experiments on graphene nanoribbons via pulling several different ribbons under different bias voltage15. Here, we proposed an alternative method via the reciprocating movements (schematic depiction in Fig. 2a), where the same molecular chain was used during bias-dependent conductance measurements. In these “lift-up” and “bring-down” procedures, the same starting point is chosen for different bias voltage to ensure the same initial environment and coordination in continues measurements. Also, the same distance and the superposition of two corresponding I(z) curves guarantee the identical configurations in repeated reciprocating motion (Supplementary Fig. 3). During the “up and down” process, the phenyl groups significantly enhance the \(\pi\)-metal interaction at the tip-molecule interface, compared to pure trans-polyene. This leads to the stabilization of the entire molecular junction, enabling lateral manipulation and lifting of the entire molecule from the surface (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, phenyl groups not only promote dehydrogenation reactions, but also stabilize this single-molecule junction.

a The conductance as a function of tip height in the same molecular junction with different bias voltage. Black, light blue, blue, light red and red curves are conductance obtained under 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 mV, respectively. The inset is a schematic illustration of the reversable conductance measurements through reciprocating movement. The conductance curves exhibit exponential decay as the tip height increases, accompanied by periodic oscillations. These oscillations can be attributed to the lifting up of a (CH)2 group within 2, occurring at a periodicity of 285\(\pm 36\) pm which is averaged over eleven independent measurements in Supplementary Table 2. The black dash line corresponds to the exponential fitting of conductance curve under 10 mV, with a decay constant (\(\beta\) value) of 0.086 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\). b The averaged decay constant (\(\beta\)) obtained from analyzing eleven independent reversable conductance measurements (fitting more than 60 conductance curves). Decay constants of ten different bias voltages all fall within the range of 0.10\(\pm\)0.02 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\), with lower \(\beta\) values in negative bias voltages compared with positive voltages. The dash gray line points at 0.1 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\). The original data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9a and Supplementary Table 2. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Conductance measurements with different electron energies

Figure 2a displays the measured conductance during lifting up process under various bias voltage ranging from 10 to 200 mV. Taking the curve obtained under 10 mV as an example, we attempted to analyze the height-dependent conductance of polyene. The value of conductance exhibits an exponential decay with overlapped oscillations, a period of 252\(\pm \,\)4 pm. When taking more curves into considerations, the averaged period is 284.8 pm (Supplementary Table 2), which locates within the 12% deviations of the repeat distance of trans-polyene on Cu(110) (255 pm in Supplementary Fig. 2). It is a typical character of a low-voltage conductance curve and has been extensively discussed as lifting up one unit-cell of oligomer chain11,22. Therefore, the oscillation arises from the detachment of one (CH)2 unit in 2 from surface, without bias-dependence. This behavior is also captured in pure trans-polyene molecules (Supplementary Fig. 3) and different molecule-tip configurations (Supplementary Fig. 9a and Supplementary Table 2).

Despite an increase in the tip-sample distance from 2.1 to 3 nm, the conductance measured on single molecule of 2 remains around \(3\times {10}^{-8}-{10}^{-7}\) S, which is the highest among the oligomer molecules or chains investigated, compared to 10−9 S in thiophene chain12, 10−10 S in polyfluorene11 and 10−8 S in (donor-acceptor-donor)n ((DAD)n) chain13. Also, this obtained conductance is much higher than the value of \({10}^{-9}\) S reported in break junction studies on carotenoid polyene23,24, and previous calculations in ref. 25. This high conductance remains relatively unaffected by varying voltage biases.

Furthermore, fitting the conductance data with the formula \(G={G}_{0}{{\rm{e}}}^{-\beta z}\) provides further insights into charge transport in single molecule of 2 or a polyene chain. The obtained decay constant for a bias voltage of 10 mV is 0.086 ± 0.003\({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\), which is close to the detection limit due to mechanical noise. This low decay constant is also presented in Fig. 2b, with weak bias-dependence. All the averaged \(\beta\) values based on more than ten molecules fall within the range of 0.10\(\pm\)0.02 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\) for bias voltage ranging from −200 to +200 mV relative to the Fermi level, within the highest occupied molecular orbital and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (HOMO-LUMO) gap of single molecule 2 (Supplementary Fig. 9a and Supplementary Table 2). Among them, the averaged \(\beta\) values are lower for negative bias and larger under positive voltage, which indicates the deviations in electronic state above and below Fermi level. Even though it presents bias-dependent, these decay constants are quite low compared with other oligomer wires: 0.4 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\) for thiophene chains12, 0.3 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\) for polyfluorene11, 0.23 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\) for (DAD)n chain13 and 0.17 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\) for another acceptor in (DAD)n chain26. Previous calculations gave a higher value 0.19 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\) by considering (LUMO-HOMO) gap and effective mass for tunneling electron25,27. In break-junction measurements of polyene-like molecules, β values of 0.22 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\)23,24, and 0.17 \({\text{\AA}}^{-1}\)28, have been reported, which are obviously higher than the one we obtained here. This low value of decay constant has been reported in measurements of polyene-like molecules with even number of carbons in oxidized state or polyenes with odd number of carbons in a symmetry configuration, where delocalized state on polyene was found28,29. As opposed to the solution environment in beak junction30, here is a simplified circumstance provided by low temperature and ultrahigh vacuum. As a result, it raises the question of whether trans-polyene chains in this case will retain their pristine characteristics or transform into a metallic state.

Calculated conductance, charge transfer, and bond length

To gain a better understanding of the mechanism behind the high conductance and low decay constant obtained in single molecule of 2, transport simulations were carried out using the Atomistix Toolkit (ATK) package31,32. Figure 3a depicts the calculated conductance as a function of electrode distance, which corresponds to the number of carbon atoms in the polyene moiety, with the phenyl-electrode configuration in a planar geometry shown in the inset. This simplified device model yields high conductance and low decay constants for different bias voltages, qualitatively similar to the experimental observations. Taking the bending of single molecule during tip manipulation into consideration, calculations reproduced low decay constant, with the same value as we obtained from experiments (Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Fig. 8).

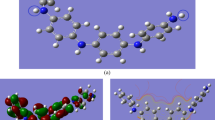

a Calculated conductance of diphenyl [n] conjugated polyene sandwiched between two copper electrodes, as a function of electrode distance (i.e., numbers of carbon atoms in polyene part of molecules (n)). The calculations are performed under bias voltage of 50 meV (blue dot), 100 mV (light red dot) and 200 mV (red dot), with exponential fittings shown as dash lines. The inset presents an example of model used in the calculations, where a single diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene molecule adsorbs on two electrodes via two phenyl groups. Circles color: bronze (copper), gray (carbon), white (hydrogen). b The difference charge density plot for the calculated transport model with diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene with side view and top view. The isosurface value is set as 0.05 e Å−1 at \(\pm\)0.005 a0−3. The symbol a0 represents the Bohr radius, and a0−3 is a unit of number density, indicating the number of entities per cubic Bohr radius. The arrows indicate the electrons transfer from C = C bonds to C-C bonds. c Structural and bond-length features of diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene. The structure of an individual diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene, its bond length alternation in gas phase and the fading bond length alternation in the calculated transport model are shown in order. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To distinguish the contribution of different constituents, the conductance of a trans-polyene molecule without phenyl modification was calculated (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 1). The influence of phenyl rings is minimal and can essentially be ignored. Therefore, the high conductance and low decay constant can be attributed to the polyene segment of 2. Earlier studies by Wang and coworkers reported a semiconductor-to-metal transition occurring upon the polyacetylene adsorption onto Cu(110), attributed to copper surface doping the polyacetylene with 0.1 electron per carbon atom19. Here, it was found an electron doping level of \(\approx\)0.42 electrons per diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene molecule, corresponding to \(\approx\)0.01 electron per carbon atom. This indicates a lightly doped polyene structure due to the partial decoupling in the lifting up process, which is dramatically different from polyacetylene on copper. Additionally, in Fig. 3b, it can be observed that the phenyl parts receive more charges from copper, further reducing the electron-doping level in the polyene segment. Consequently, the polyene segment remains semiconducting rather than becoming metallic.

Despite the limited amount of transferred charge, it still induces electron redistribution within the polyene moiety. As indicated by arrows in Fig. 3b, electrons transfer from C = C bonds to C-C bonds, resulting in a more uniform electron density distribution across the entire polyene segment. The strong electron-phonon interaction leads to variation in bond length at the same time (Fig. 3c). In the case of an individual diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene molecule (similar to 2), the polyene part exhibits the Peierls bond length alternation with single bonds (1.42 \({\text{\AA}}\)) and double bonds (1.37 \({\text{\AA}}\)), which gets even larger during stretching (Supplementary Note 4). For the lightly-doped molecule in the calculation model, the discrepancy between the single and double C-C bonds diminishes, and they fall within the range of 1.39-1.41 \({\text{\AA}}\). This nearly uniform bond length distribution suggests that doping directly influences the bond order due to the electron-phonon coupling in polyene, which would affect the electronic state inside this molecular junction simultaneously.

Fermi-level pinning and electron-phonon coupling

Energy-resolved measurement is crucial for exploring the high conductance and low decay constants. Figure 4a presents the scanning tunneling spectroscopy of tip-2-surface junction at a tip height of 2.2 nm. The differential conductance signal exhibits an increase around \(\pm \)800 mV, with some features shown at low bias voltage. A magnified view of these characteristics (Fig. 4a, inset) presents an electronic state at −20 mV. This feature around Fermi surface is captured by different tips with variations of peak position and intensity, with an averaged value locating at −23.4 mV (Supplementary Fig. 9b and Supplementary Table 3). Meanwhile, our calculations confirm the presence of an electronic state around Fermi level following the adsorption of molecules on copper electrodes, as shown in Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 8b, which also works for single all-trans polyene molecule in Supplementary Fig. 5. The transmission state appears at 25 meV above the Fermi level, with minimal variation for different molecular lengths, a phenomenon termed as Fermi-level pinning33,34,35. The proposed explanation for it is shown in Fig. 4d, where LUMO of diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene aligns closely with the Fermi level of copper (Supplementary Note 2). In long molecular chains, the reductions of HOMO-LUMO gap create a compensating dipole moment to prevent the orbital from crossing the Fermi level. Also, this transmission eigenstate occupies the C-C single bonds, exhibiting a spatial distribution similar to the LUMO orbital of diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene (Supplementary Fig. 6). As a result, this frontier orbital dominates the charge-transport process in molecular chains, bringing it from out-of-resonant tunneling to on-resonant tunneling. It explains the decay constants for negative bias voltage is lower than those of positive bias. This is further confirmed when the pinning electronic state fades away in the height-dependent differential conductance measurements: the conductance drops fast when tip height is larger than 3 nm (Supplementary Fig. 10), indicating the on-resonant tunneling transforming to off-resonant tunneling. This is captured in calculations based on bended single molecule (Supplementary Fig. 8b), indicating the weakened contribution of molecule-electrode interface during molecular length increasing. Moreover, p states of phenyl groups can hybridize with d states of copper and create another coupling pathway for charge transport. It has been demonstrated that increasing the electron delocalization of terminal groups and the number of coupling electronic channels at the contact can enhance the coupling strength and reduce the contact resistance in molecular junctions36,37,38. Therefore, Fermi level pinning and the enhanced electronic coupling at the interface afford the larger conductance and lower decay constant. This highlights the pivotal role of the molecule-electrode interface in determining conductive properties in electric field.

a Scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS, black curve) and inelastic electron tunneling spectroscopy (IETS, gray curve) of single molecule of 2. The STS plot reveals an increasing electronic state around \(\pm \)800 mV, with a peak observed around zero energy. The inset displays the STS with a smaller voltage range with the corresponding IETS. The red shadow region marks the peak around −19 mV. Two signals in IETS indicate two vibrational modes, the stretching mode of C-C bonds at 135 meV and C = C bonds at 185 meV. More statistical data about STS and IETS are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 3. b The calculated projected density of states (DOS) of diphenyl [n] conjugated polyene sandwiched between two copper electrodes. It presents a pinned frontier orbital around zero energy for various molecular lengths. The purple arrow, orange arrow and brown arrow assign three peaks of a diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene molecule with specific molecular orbitals, which is similar for other molecules. c A schematic diagram of two vibrational modes of a diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene molecule in the calculation model. d Illustration of Fermi-level pinning formed at the molecular-electrode interface in this case. Blue and bronze regions mark the occupation of electron in molecular orbitals and copper electrode. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Meanwhile, this pinned molecular orbital effectively improves the possibility of exciting the molecular vibration during tunneling, resulting in four step-like features in dI/dV measurement shown in Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9b–d. To magnify these vibrational signals, inelastic elastic tunneling spectroscopy (IETS) was carried out, revealing two centrosymmetric groups of peaks around 135 and 185 meV. These two modes correspond to the stretching vibrations of the backbone C-C and C = C bonds (Fig. 4c), which have also been observed in the calculated infrared spectroscopy of diphenyl [20] conjugated polyene molecules (Supplementary Fig. 7) and previous spectroscopic measurements of polyene39,40. Due to the high sensitivity of vibrational spectroscopy to chemical environments, the attenuated bond alternation weakens the stretching of C-C bonds and C = C bonds, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. The energies of these two modes are lower than those of an individual molecule, with the stretching vibration of C-C bonds decreased from 148 to 136 meV, and the stretching mode of C = C bonds reduced from 206 to 193 meV. These calculated energies closely match those obtained from IETS measurements (inset in Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 9, 10), which are 135.6 meV for C-C bonds and 184.1 meV for C = C bonds shown in Supplementary Table 3, respectively. Additionally, these vibrational modes over the backbone of 2 open up new channels for charge transport by transferring energy to molecular vibrations during electron tunneling, which contributes to the highest conductance observed under a bias voltage of 200 mV, as shown in Fig. 2a. Although the appearance of inelastic signals stems from the strong electron-vibration coupling, the decay in conductance is predominantly governed by the molecular orbitals rather than the inelastic process. It is confirmed via the increasing decay constant during tip raising higher, along with reduced electronic state and inelastic signals (Supplementary Fig. 10). This explains the observation of similar decay constants for 200 mV and other bias voltages.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a method to measure conductance of a single molecule under different voltage via reciprocating motion, which provides a simple way to investigate molecular junction based on single “lifting-up” process by an STM tip. Here, the measurement of charge transport in a single polyene-based molecule was carried out, with molecules synthesized through an on-site surface reaction. The conductance of this single molecule with trans-polyene part was found to be the highest one among previous synthesized oligomer chains of similar length by surface on-site reaction, as well as the lowest decay constant. These findings were well reproduced by the nonequilibrium Green’s functions (NEGF) simulations, which involved trans-polyene based molecules adsorbed horizontally on planar Cu(110) electrodes. With less than 2% electron doping per carbon atom, the molecule remained a semiconductor, contrary to previous reports of a metallic state. However, the frontier molecular orbital is pinned to around Fermi level, which are captured both in energy-resolved spectroscopy and calculations. This on-resonant tunneling, along with improved molecule-electrode coupling, greatly enhances the conductance and lower the decay process during lifting up process, which transforms to off-resonant tunneling with increasing tip height. It strongly emphasizes the energy-level alignment and the interfacial effects, both of which change the charge-transport process under electrical field. Despite the consistence between our experimental results and calculations, we cannot rule out the possibility of soliton formation due to the presence of in-gap state and convergent stretching mode of C-C bond, which requires further investigation and clarification.

Methods

STM measurements

All the samples were prepared with commercial low-temperature scanning tunneling microscopy (Unisoku LT-STM 1500 s) with a base pressure better than 1 × 10−10 torr at 4.7 K. The bias is applied to the sample, with the tip grounded. The Cu(110) surface (Mateck, Germany) was prepared through cycles of Ar+ sputtering (1.5 keV) and annealing up to 750 K. Octadecyl benzene (Aladdin, >95%) were evaporated onto the substrate held at room temperature using a commercial Knudsen cell from Kentax (Germany). During this process, phenyl [18] conjugated polyene (1) is formed via cascade dehydrogenation at 400 K. Further annealing the Cu(110) sample at 473 K for 30 min to produce diphenyl [36] conjugated polyene (2) via trans-intercoupling of molecules of 1. The up limit of preamplifier is switched between 10 nA for high resolution imaging and 100 nA for conductance measurements. Scanning tunneling spectroscopy was carried out by a lock-in amplifier, with the sample bias modulated by a 271 Hz, 5-10 mV (rms) sinusoidal voltage. dI/dV data and IETS data shown in main text are average for more three times and more than ten times, respectively. The STM images were analyzed using the WsXM software41.

Theoretical calculations about charge-transport process

The transport simulations of single-molecule device are performed using density functional theory (DFT) combined with NEGF42,43, as implemented in Atomistix Toolkit (ATK) software (version: R-2021.06). The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with spin dependent Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional is employed to describe the exchange–correlation potential44. The details of optimized structures are also checked using hybrid HSE functional (see Supplementary Note 3). The transport device model is divided into three parts, i.e., left and right electrodes and central region. The geometrical structure of conjugated polyene is optimized until the maximum force on each atom is less than 0.03 eV Å−1. For molecular junction optimization, the force and energy criterion are set as 0.05 eV Å−1 and 10−4 eV, respectively. A density mesh cut off energy of 100 Hartree and 1 × 4 × 150 Monkhorst-Pack k-point sampling are utilized. The transmission coefficient \({T}_{\sigma }\left(E,V\right)\) is given by:

To describe the interlayer charge transfer between molecule chain and electrodes precisely, we performed Bader analysis on the structure of ATK in Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP). For the property calculation, the plane wave cutoff energy and energy convergence are set as 500 eV and 10−6 eV, respectively.

Calculations about dehydrogenation process and molecular configurations

DFT calculations for the dehydrogenation process and adsorbed configurations were performed using the VASP together with the python package Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE)45,46. The projector augmented wave (PAW) potential47 was applied to describe the electron-ion interactions, and the van der Waals density functional48 (vdWDF) was applied to describe the exchange-correlation effects, which was proposed by Hamada49 and denoted as rev-vdWDF2. The transition states were searched by the combination of the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) and the dimer methods50,51.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Joachim, C. & Ratner, M. A. Molecular electronics: Some views on transport junctions and beyond. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 8801–8808 (2005).

Okawa, Y. et al. Chemical wiring and soldering toward all-molecule electronic circuitry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8227–8233 (2011).

Facchetti, A. pi-conjugated polymers for organic electronics and photovoltaic cell applications. Chem. Mater. 23, 733–758 (2011).

Muench, S. et al. Polymer-based organic batteries. Chem. Rev. 116, 9438–9484 (2016).

Fratini, S. et al. Charge transport in high-mobility conjugated polymers and molecular semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 19, 491–502 (2020).

Shirakawa, H. et al. Synthesis of electrically conducting organic polymers—halogen derivatives of polyacetylene, (Ch)X. J. Chem. Soc.-Chem. Commun. 16, 578–580 (1977).

Heeger, A. J. Nobel lecture: Semiconducting and metallic polymers: The fourth generation of polymeric materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 681–700 (2001).

Shirakawa, H. Nobel lecture: The discovery of polyacetylene film—the dawning of an era of conducting polymers. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 713–718 (2001).

Su, W. P. et al. Solitons in polyacetylene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 42, 1698–1701 (1979).

Meier, E. J. et al. Observation of the topological soliton state in the Su-Schrieffer-Heeger model. Nat. Commun. 7, 13986 (2016).

Lafferentz, L. et al. Conductance of a single conjugated polymer as a continuous function of its length. Science 323, 1193–1197 (2009).

Reecht, G. et al. Electroluminescence of a polythiophene molecular wire suspended between a metallic surface and the tip of a scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 047403 (2014).

Nacci, C. et al. Conductance of a single flexible molecular wire composed of alternating donor and acceptor units. Nat. Commun. 6, 7397 (2015).

Kuang, G. W. et al. Resonant charge transport in conjugated molecular wires beyond 10 nm range. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11140–11143 (2016).

Koch, M. et al. Voltage-dependent conductance of a single graphene nanoribbon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 713–717 (2012).

Jacobse, P. H. et al. Electronic components embedded in a single graphene nanoribbon. Nat. Commun. 8, 119 (2017).

Lawrence, J. et al. Probing the magnetism of topological end states in 5-armchair graphene nanoribbons. ACS Nano 14, 4499–4508 (2020).

Friedrich, N. et al. Addressing electron spins embedded in metallic graphene nanoribbons. ACS Nano 16, 14819–14826 (2022).

Wang, S. Y. et al. On-surface synthesis and characterization of individual polyacetylene chains. Nat. Chem. 11, 924–930 (2019).

Li, X. C. et al. Direct transformation of n-alkane into all-trans conjugated polyene via cascade dehydrogenation. Natl Sci. Rev. 8, nwab093 (2021).

Su, C. et al. Core-level photoemission and work-function investigation of Na on Cu(110). Phys. Rev. B 48, 12146–12150 (1993).

Kawai, S. et al. Quantifying the atomic-level mechanics of single long physisorbed molecular chains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 111, 3968–3972 (2014).

Meisner, J. S. et al. A single-molecule potentiometer. Nano Lett. 11, 1575–1579 (2011).

He, J. et al. Electronic decay constant of carotenoid polyenes from single-molecule measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 1384–1385 (2005).

Magoga, M. & Joachim, C. Conductance and transparence of long molecular wires. Phys. Rev. B 56, 4722–4729 (1997).

Skidin, D. et al. Tuning the conductance of a molecular wire by the interplay of donor and acceptor units. Nanoscale 10, 17131–17139 (2018).

Joachim, C. & Magoga, M. The effective mass of an electron when tunneling through a molecular wire. Chem. Phys. 281, 347–352 (2002).

Visoly-Fisher, I. et al. Conductance of a biomolecular wire. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8686–8690 (2006).

Gunasekaran, S. et al. Near length-independent conductance in polymethine molecular wires. Nano Lett. 18, 6387–6391 (2018).

Evers, F. et al. Advances and challenges in single-molecule electron transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 035001 (2020).

Brandbyge, M. et al. Density-functional method for nonequilibrium electron transport. Phys. Rev. B 65, 165401 (2002).

Wang, B. et al. Current partition: A nonequilibrium green’s function approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 398 (1999).

Merino-Diez, N. et al. Width-dependent band gap in armchair graphene nanoribbons reveals fermi level pinning on Au(111). ACS Nano 11, 11661–11668 (2017).

Niederhausen, J. et al. Doping of C-60 (sub)monolayers by Fermi-level pinning induced electron transfer. Phys. Rev. B 86, 081411(R) (2012).

Braun, S. et al. Energy-level alignment at organic/metal and organic/organic interfaces. Adv. Mater. 21, 1450–1472 (2009).

Mishchenko, A. et al. Single-molecule junctions based on nitrile-terminated biphenyls: A promising new anchoring group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 184–187 (2011).

Martin, C. A. et al. Fullerene-based anchoring groups for molecular electronics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 13198–13199 (2008).

Kamenetska, M. et al. Conductance and geometry of pyridine-linked single-molecule junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6817–6821 (2010).

Ehrenfreund, E. et al. Amplitude and phase modes in trans-polyacetylene: Resonant Raman scattering and induced infrared activity. Phys. Rev. B 36, 1535–1553 (1987).

Shirakawa, H. & Ikeda, S. Infrared spectra of poly(acetylene). Polym. J. 2, 231–244 (1971).

Horcas, I. et al. WSXM: A software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78, 013705 (2007).

Taylor, J. et al. Ab initio modeling of quantum transport properties of molecular electronic devices. Phys. Rev. B 63, 245407 (2001).

Soler, J. M. et al. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-N materials simulation. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 14, 2745 (2002).

Troullier, N. & Martins, J. A straightforward method for generating soft transferable pseudopotentials. Solid State Commun. 74, 613–616 (1990).

Larsen, A. H. et al. The atomic simulation environment-a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Dion, M. et al. Van der Waals density functional for general geometries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 246401 (2004).

Hamada, I. van der Waals density functional made accurate. Phys. Rev. B 89, 121103(R) (2014).

Kaestner, J. & Sherwood, P. Superlinearly converging dimer method for transition state search. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 014106 (2008).

Kuhne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package—Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21790053, 51821002, 22072103, 22161132026 (L.C), 22102109 (S.Y), 22322304 (X.L.) and 22288201 (J.Y)), the Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou Nano Science and Technology (L.C), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD) (L.C), the Suzhou Key Laboratory of Surface and Interface Intelligent Matter (grant SZS2022011) (L.C), and Jiangsu Excellent Postdoctoral Program (2024ZB117) (S.Y).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. C. and Xingxing Li designed and supervised the project. S. Y., Xuechao Li and J. X. performed the STM-based conductance measurements, C. Y., Xingxing Li, J. Y., G. P., K. N., Y. G. and S. D. performed theoretical calculations. C.X. contributed to the discussion about explaining the observations. All authors worked on the interpretation of the data and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, S., Yu, C., Gao, Y. et al. Quantifying the conductivity of a single polyene chain by lifting with an STM tip. Nat Commun 15, 6475 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50915-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50915-8