Abstract

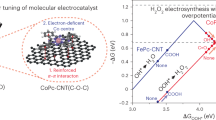

The incorporation of multiple immiscible metals in high-entropy oxides can create the unconventional coordination environment of catalytic active sites, while the high formation temperature of high-entropy oxides results in bulk materials with low specific surface areas. Here we develop the high-entropy LaMnO3-type perovskite-polyoxometalate subnanowire heterostructures with periodically aligned high-entropy LaMnO3 oxides and polyoxometalate under a significantly reduced temperature of 100 oC, which is much lower than the temperature required by state-of-the-art calcination methods for synthesizing high-entropy oxides. The high-entropy LaMnO3-polyoxometalate subnanowires exhibit excellent catalytic activity for the photoelectrochemical coupling of methane into acetic acid under mild conditions (1 bar, 25 oC), with a high productivity (up to 4.45 mmol g‒1cat h‒1) and selectivity ( > 99%). Due to the electron delocalization at the subnanometer scale, the contiguous active sites of high-entropy LaMnO3 and polyoxometalate in the heterostructure can efficiently activate C − H bonds and stabilize the resulted *COOH intermediates, which benefits the in situ coupling of *CH3 and *COOH into acetic acid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Rost group proposed a novel class of oxides, known as entropy stabilized oxides ((NiMgCuZnCo)0.2O), in 20151. Subsequently, high entropy oxides (HEOs) have been extensively investigated due to their exceptional stability surpassing that of unary and binary counterparts2,3,4. Moreover, the presence of metal cations in unconventional coordination environments often imparts HEOs with numerous unforeseen physico-chemical properties5,6,7. The design of a single high entropy phase is guided by Gibbs free energy (ΔGmix, ΔGmix = ΔHmix – TΔSconf), wherein ΔHmix and ΔSconf represent the enthalpy change upon mixing and configurational entropy respectively6,8. Furthermore, within this framework, the entropic contribution (TΔSconf) can play a dominant role8. Based on this principle, the family of HEOs has witnessed significant expansion encompassing diverse oxide types ranging from rocksalts and perovskites to spinels and fluorites9. However, the incorporation of multiple elements in HEOs is typically done in significant proportions, and the inherent complexities between these elements (such as differences in atomic radii and high mixing enthalpy for solid solution formation) make them susceptible to phase separation or element segregation8. To achieve uniform and random occupation of similar sites by metal cations, elevated reaction temperatures are usually required. For example, the work of Rost group considered a temperature of 1000 °C since CuO and ZnO were not expected to crystallize in a rocksalt phase10. Unfortunately, these high temperatures often lead to pore collapse and the disappearance of defects, thereby hindering the application of HEOs in the catalysis community6,11. Due to the unsaturated coordination of surface atoms with ultrahigh ratios, lattice distortion and atomic rearrangement may occur in subnanomaterials (SNMs), which brings a notably increased entropy compared with their nano-sized counterpart12. Therefore, a much lower reaction temperature can be expected in the synthesis of HEO-SNMs.

The oxidative coupling of methane (OCM) for C − C bond formation possess important values in both science and economics13, yet remains a great challenge due to the stable C − H bonds14,15. Photoelectrochemical (PEC) catalysis offers an efficient way for the methane activation under ambient conditions without oxidants16,17,18. During the reaction, C − H bonds can be activated by the photo-generated reactive oxygen species (i.e., ·OH) under electronic fields16,18. In order to achieve C − C coupling and obtain desired C2 products with high selectivity, contiguous active sites with precisely controlled coordination environment should be essential, which is the main drawback for the design and synthesis of the state-of-art catalysts19,20,21. At ambient conditions, the activation of CH4 can be facilitated by photocatalysts comprising BiVO4, WO3 or noble metal supports (e.g., Au, Ag, Pt, Pd) on TiO2 and ZnO. However, the utilization of HEOs catalysts for light-induced partial oxidation of CH4 remains unaccomplished19,20.

Polyoxometalates (POMs) are atomic-precision clusters with high stability toward electron lose and gain, which can serve as the electron buffer for the tuning of photo- and electro-catalysis22,23. The presence of POMs in catalysts has been reported to significantly decrease the productivity of gas phase products, while greatly enhancing the selectivity of liquid phase products24,25. This suggests that the involvement of delocalized electrons in the outer layer of POMs may play a crucial role in stabilizing intermediates other than methyl and methylene groups26. The oxygen covered surface of POM clusters enables the direct bonding of metal oxides with different configurations, for which HEO nuclei could be captured by POM clusters to form stable HEO-POM sub-1 nm hetero-structures27,28. The presence of delocalized electrons across subnanomaterials serves to stabilize critical intermediates during the oxidation of methane, effectively inhibiting their overoxidation23,26. Perovskite oxides of the ABO3-type exhibit excellent CH4 activation abilities due to their distinctive electronic structure29. Additionally, the valence band of ABO3 possesses a lower potential compared to the oxidation potential of CH4, thereby rendering the photogenerated holes in the valence band thermodynamically favorable for facilitating CH4 oxidation15,30. We hereby prepare high-entropy LaMnO3-type perovskite-POM (HELMO-POM) nanowires of 1.8 nm in-width with long-ranged (-p-n-p-n-)n type hetero-structures, where the HELMO units involve elements of La, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni (La(CrMnFeCoNi)0.2O3‒x). Under PEC system, the HELMO-POM nanowires display fine catalytic activity for OCM, with a remarkable acetic acid productivity (up to 4.45 mmol g−1cat h−1) and high selectivity ( > 99%). The OCM reaction can be proceed at room temperature and ambient pressure without oxidants, superior to the reported electrocatalysts and photocatalysts. During the reaction, the photo-generated electron–hole pairs can be efficiently separated by the periodic interface of HELMO and POM units with a carrier transfer distance at sub-1 nm scale, which acts as the primary sites for C − H bond activation. Meanwhile, the active intermediates *COOH can be stabilized by the delocalized electrons in POM clusters, resulting in high selectivity for acetic acid formation. The unique electronic structure of (-p-n-p-n-)n type sub-1 nm hetero-structure manipulated by HELMO and POM units may enlighten the design of advanced catalysts for efficient oxidative coupling of CH4 under mild conditions.

Results

Preparation and characterizations of the high-entropy subnanomaterials

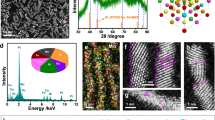

The HELMO-PTA subnanowires (subnano-HELMO-PTA) were synthesized using the cluster–nuclei co-assembly strategy31, in which phosphotungstic acid (PTA) clusters and HELMO nuclei were integrated into subnanometer assemblies through direct bonding in the form of hetero-units (Fig. 1a)32. During the solvothermal reaction, rare earth element ions (La3+) and five transition metal ions (Cr3+, Mn3+, Fe3+, Co2+ and Ni2+) formed HELMO crystal nuclei in the first step. The second step involved the capture of these HELMO nuclei by PTA, leading to their restricted size growth and subsequent co-assembly into subnanowires. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images revealed that the subnano-HELMO-PTA appeared as twisted nanowires with a consistent width, as shown in Fig. 1b. High angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image in Fig. 1c indicated that the width of subnano-HELMO-PTA was approximately 1.8 nm. When PTA was absent in the system, the formation of HELMO nuclei was still observed; however, without the constraining effect of PTA on their size growth, these HELMO nuclei underwent uncontrolled development into nanowires with varying sizes (Supplementary Fig. 1). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) result in Fig. 1d revealed that the obtained subnano-HELMO-PTA exhibited a single cubic perovskite phase (162002-ICSD, The Inorganic Crystal Structure Database). Moreover, the high resolution TEM (HRTEM) image in Supplementary Fig. 2 displayed a lattice spacing of 2.71 Å corresponding to the (011) crystal plane of LaMnO3, with no evidence of secondary phases. The elemental mapping images obtained from X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) suggested a homogeneous distribution of La, W, P and transition metals across subnano-HELMO-PTA (Fig. 1e).

The chemical state and coordination environment of the Fe center and Ni center in subnano-HELMO-PTA were investigated using X-ray absorption fine structure analysis, including X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) techniques (Fig. 2a,b). The EXAFS Fourier transform of subnano-HELMO-PTA exhibited a dominant peak at approximately 1.43 Å and 1.51 Å, respectively, which corresponded to the Fe−O and Ni−O scattering paths as shown in Fig. 2c,d (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, weak scattering peaks were observed for the Fe−Fe or Ni−Ni bonds in subnano-HELMO-PTA. The coordination configurations of the Fe and Ni centers in the subnano-HELMO-PTA were further investigated (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). An average coordination number (CN) of approximately 6.0 was determined for Fe and Ni, respectively, across the subnano-HELMO-PTA, which was consistent with the coordination number of transition metals in the B-site of LaMnO3-type perovskite (refer to Supplementary Fig. 4). Additionally, the wavelet transform results (WT, see Fig. 2e,f) displayed only one higher intensity maximum at 4.1 Å−1 and 4.2 Å−1 in k space associated with the Fe−O bond and Ni−O bond, respectively. These findings indicated that both Fe and Ni atoms were atomically incorporated into the B-site of LaMnO3-type perovskite while being coordinated by O atoms. The crystalline structure of subnano-HELMO-PTA was further analyzed using Raman spectra (Supplementary Fig. 5a), which demonstrated a series of Raman peaks that could be attributed to cubic LaMnO3-type perovskite oxide (Pm3m, space group 221). Consequently, we proposed that five types of transition metal ions (Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni) were successfully incorporated into the sublattice of LaMnO3, thus confirming the successful synthesis of high-entropy LaMnO3-PTA subnanowires. Besides, the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum suggested the well incorporation of PTA in subnano-HELMO-PTA (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

According to the results of inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES), the element ratios of La: Cr: Mn: Fe: Co: Ni: W: P were measured to be 1: 0.2: 0.2: 0.21: 0.18: 0.18: 1.01: 0.09, which was close to the W: P ratio in PTA. Based on this, we calculated the ΔSconf of subnano-HELMO-PTA to be 13.11 J mol−1 K−1, which was close to the ideal value of HEOs (Supplementary Table S3). The density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Note 1) revealed that the formation temperature (Tform) of ternary La3(CrMnCo)O9 (medium-entropy LaMnO3, MELMO) from the corresponding unary oxide was predicted to be 1226 K, whereas the quinary La5(CrMnFeCoNi)O15 could form a single-phase structure at a temperature of just 1074 K (Supplementary Fig. 6). This result indicated the entropy-driven mixing effect and highlighted the necessity of high temperature for achieving single-phase HEOs formation. However, in this work, high-entropy LaMnO3 was synthesized at 373 K, significantly below both its predicted formation temperature and the most used sol-gel method for synthesizing LaMnO3 catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 7). The subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst offered a higher density of catalytic sites in the reaction compared to the bulky HELMO synthesized at high temperatures (e.g., 1000 K). This achievement can be attributed to the advantages offered by our co-assembly strategy and distinct role of PTA (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Photoelectrochemical methane oxidation performance of subnano-HELMO-PTA

To evaluate the photoelectrochemical (PEC) performance of CH4 oxidation under ambient conditions, a 3-electrode electrochemical system was constructed with micro-porous aeration tube (Supplementary Note 2), Pt foil as the counter electrode, Ag/AgCl electrode as reference electrode, and a xenon lamp (Beijing Perfectlight, Microsolar 300) with a spectrum ranging from 320 to 780 nm (Supplementary Fig. 9). The liquid products were analyzed through 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR). Gas products (C2H2, C2H4, C2H6, CO and CO2) were analyzed using gas chromatography. In the absence of CH4, namely in an argon (Ar) saturated system, the current density of the subnano-HELMO-PTA sample was primarily attributed to oxygen evolution reaction (OER) (Fig. 3a)16. Subsequently, a significant increase in current density was observed between 0.6 V and 1.4 V after introducing CH4 into the reaction system. Simultaneously, there was a distinct shift towards lower potential for onset on subnano-HELMO-PTA (Fig. 3a), indicating that CH4 oxidation on this material was preferred over OER. Besides, the subnano-HELMO-PTA sample exhibited a productivity of 1.81 mmol g−1cat h−1 and a selectivity above 99% for the oxidative coupling of CH4 to acetic acid (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 4).

a The linear sweep voltammogram (LSV) of subnano-HELMO-PTA in Ar-saturated and lighting system (black line), CH4-saturated and dark system (red line) and lighting system (prussian blue line). b PEC results of subnano-HELMO-PTA in Ar-saturated system under lighting condition and CH4-saturated system in dark and lighting condition. c Productivity and selectivity of acetic acid with 0.75 mg subnano-HELMO-PTA as catalysts under a range of potential. d LSV curves of different samples. e Productivity and selectivity of acetic acid of different samples. f I–t curves of different samples under 1.0 V. g LSV curves of samples with different ΔSconf. h Productivity and selectivity of acetic acid of samples with different ΔSconf. Reaction condition: 0.75 mg catalyst, 0.5 M Na2CO3 as the electrolyte (150 mL) and light intensity equaled 100 mW/cm2. i Isotopic labeling experiments were carried out at 1.4 V for 6 h using 13CH4/Ar-saturated and 12CH4-saturated 0.5 M Na2CO3 electrolyte to demonstrate by 1H NMR spectroscopy that the acetic acid was produced from CH4. The mean values in catalytic performance were estimated from three independent (n = 3) measurements, and the data were presented as mean values ± s.d.

After the introduction of an external light field into the reaction system, the current density exhibited a further increase from 18.6 to 28.2 mA cm−2 at 1.2 V (Fig. 3a). As a photosensitizer, subnano-HELMO-PTA can effectively utilize UV-visible light for CH4 activation (Supplementary Fig. 10). Therefore, the external light field could enhance the efficiency of CH4 conversion (Supplementary Fig. 11a), leading to increased acetic acid productivity while maintaining selectivity towards acetic acid (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table 4). The conversion of methane to acetic acid necessitates the presence of 8 photo-generated holes (h+)33. Sustaining this current disparity in chronoamperometric measurements for a duration of one hour theoretically yields 257.8 µmol of acetic acid (Supplementary Note 3). However, there existed a substantial disparity between the anticipated productivity of acetic acid and the actual experimental outcomes. Hence, we proceeded to calculate the Faradaic efficiencies (FEs) for all products during PEC conversion of CH4. Supplementary Fig. 13 illustrated that at an applied bias of 1.2 V, the FE for acetic acid was determined to be 17.4%, while the FE for O2 stood at 80.1%. Consequently, it can be inferred that not all h+ generated in the PEC reaction were utilized solely for oxidizing methane and producing acetic acid; a significant portion also participated in facilitating the OER. Additionally, no products were generated in an Ar-saturated system, indicating that the carbon source for PEC conversion of CH4 originated solely from CH4 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 4).

Similarly, the applied potential exerted a significant impact on the PEC conversion of CH4. Elevating the anode potential can facilitate surface photo-generated electron transfer and suppress surface photo-generated carrier recombination, thereby enhancing reactive oxygen species radical production on the subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst surface. However, the rate of competing OER and consequently the yield of acetic acid can be affected by an increase in the higher potential16,17. Subsequently, PEC conversion of CH4 was conducted at 0.6–1.6 V. When the applied potential was low (e.g., 0.6 V), the liquid products primarily comprised ethanol and acetic acid (Fig. 3c). At an applied potential of 1.2 V, subnano-HELMO-PTA exhibited a productivity of acetic acid as high as 4.45 mmol g−1cat h−1 and achieved a selectivity for acetic acid exceeding 99%. Remarkably, the selectivity towards acetic acid remained consistently above 99% and exhibited insensitivity to applied potentials when the bias exceeded 1.2 V (Fig. 3c), indicating that *COOH prior to carbon–carbon coupling can be effectively stabilized on the subnano-HELMO-PTA surface, thereby preventing over-oxidation to CO2.

To assess the respective contributions of HELMO and PTA across subnano-HELMO-PTA, three control catalysts were prepared, namely nano-HELMO, HELMO/PTA, and pure PTA. The sample of HELMO/PTA exhibited feeble interaction between HELMO and PTA clusters (Supplementary Fig. 14). As depicted in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 15, subnano-HELMO-PTA demonstrated the highest photo-current density and the lowest onset potential for CH4 activation under both illuminated and dark condition. Due to the effective segregation of photo-generated electrons and holes (Supplementary Fig. 11c), which prevented recombination of photo-carriers, subnano-HELMO-PTA demonstrated superior productivity and selectivity towards acetic acid (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Table 5). Although PTA clusters were capable of oxidizing CH4 to acetic acid, they exhibited poor stability under lighting conditions, resulting in a gradual decline in photo-current density for both HELMO/PTA and PTA samples over the course of one hour (Fig. 3f). We proposed the strong interaction between HELMO and PTA clusters could stabilize PTA and thus protecting PTA against dissociation under lighting. Due to the subnanostructure and strong interaction between HELMO and PTA clusters, the acetic acid yield and selectivity of the subnano-HELMO-PTA were found to be higher than those of previously reported electro- and photo-catalysts in OCM without an added oxidant at room temperature and ambient pressure (Supplementary Table 6).

In order to investigate the role of ΔSconf in PEC performance, we prepared samples with different ΔSconf. Specifically, we synthesized LaMnO3-PTA subnanowires (subnano-LMO-PTA) with a ΔSconf value of 0 J mol−1 K−1 and medium-entropy LaMnO3-PTA subnanowires (subnano-MELMO-PTA) with a ΔSconf value of 9.13 J mol−1 K−1 (Supplementary Fig. 16). Our findings indicated that entropy played a crucial role in lowering the onset potential for PEC conversion of CH4 (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, compared to its counterparts with no or medium ΔSconf values, subnano-HELMO-PTA exhibited the highest productivity and selectivity towards acetic acid under identical conditions (Fig. 3h, Supplementary Fig. 17, and Supplementary Table 7). We hypothesized that this superior catalytic activity could be attributed to the high crystallinity of subnano-HELMO-PTA, which endowed by the homogeneous nature of HEOs34,35. Isotopic labeling experiments were conducted using a 13CH4/Ar (1:9, v/v) mixture. PEC tests were performed at an applied potential of 1.4 V for 6 h, and subsequent analysis by 1H NMR confirmed that the acetic acid was exclusively derived from CH4, as evidenced by the observed peak splitting (JC–H coupling) under a 13CH4/Ar atmosphere (Fig. 3i). The carbonate electrolyte used in these isotopic labeling experiments was prepared by saturating either 12CH4 or 13CH4/Ar into a Na2CO3 solution with a concentration of 0.5 M. It is widely recognized that the photoelectrostability of a photocatalyst plays a pivotal role in practical applications during PEC reactions. Therefore, it was imperative to evaluate the photoelectrostability of subnano-HELMO-PTA. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 18a, the yield and selectivity of acetic acid exhibited a slight impact over subnano-HELMO-PTA after 10-cycle testing, showcasing its exceptional long-term photoelectrostability.

Mechanism insights into the activation of methane

The inferior performance of PEC activity in these control catalysts clearly indicated that the superior activity of subnano-HELMO-PTA cannot be solely attributed to the factors already present in these materials. There must exist some unique local structures in subnano-HELMO-PTA that were essential for activating CH4 molecules. The atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM image revealed a sub-1 nm scale (-p-n-p-n-)n type hetero-construction36,37, where the HELMO nuclei and PTA cluster represented p-type and n-type regions, respectively (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 19). The surface potential of the subnano-HELMO-PTA was evaluated using Kanata’s model38, which proposed that the intensity of p-n hetero-junction was determined by the surface potential. Therefore, an AFM-based surface potential mapping technique was employed to assess the strength of surface potential in subnano-HELMO-PTA. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 20a, the surface potential of HELMO/PTA was measured at 203 mV under dark conditions. Upon illumination, this value decreased to 188 mV (Supplementary Fig. 20b). Conversely, prior to exposure to external light fields, the surface potential along a straight line across subnano-HELMO-PTA was approximately 305 mV (Fig. 4b); however, after introduction of an external light field (Fig. 4c), this value decreased to 230 mV. These results indicated that subnano-HELMO-PTA has a higher electron accumulation on its surface. When excited by light, the photogenerated electrons rapidly migrated to the HELMO portion due to the strong internal electric field between PTA and HELMO, resulting in an increase of electrons on the surface of subnano-HELMO-PTA and a reduction in surface potential energy. The photogenerated carrier separation efficiency was evaluated using photoluminescence (PL) spectra. The subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst exhibited a lower PL intensity compared to the HELMO/PTA catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 21a). To measure the PL lifetime, a time-resolved PL spectrum was utilized. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 21b, the subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst demonstrated slower PL decay kinetics with an extended PL lifetime of 0.83 ns, surpassing that of HELMO/PTA (0.7 ns), thereby indicating superior carrier separation efficiency for the subnano-HELMO-PTA composite (Supplementary Table 8).

a Atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM image of HELMO-PTA subnanowires. b In situ AFM test before irradiation. c In situ AFM test after light irradiation. d–i W 4 f (d), Ni 2p (e), Co 2p (f), Cr 2p (g), Mn 2p (h), and Fe 2p (i) XP spectra of subnano-HELMO-PTA in dark and under irradiation. In terms of the Ni element, its 2p3/2 peak closely overlaps with the 3d3/2 peak of La element in XPS analysis. Consequently, it tended to be erroneously attributed to La at baseline, resulting in an elevated signal-to-noise ratio.

The subnano-HELMO-PTA was presented as a hetero-junction of the (-p-n-p-n-)n type at a sub-1 nm scale, as previously reported. In situ X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were conducted to assess charge transfer behavior under light irradiation. As illustrated in Fig. 4d, the dominant W XPS signals at 36.7 and 34.5 eV under dark conditions were attributed to W 4d5/2 and 4d7/2, respectively, indicating the +5 or +6 oxidation state of W in subnano-HELMO-PTA24,37. Upon irradiation with light, the peaks of interest assigned to Ni 2p3/2 and Co 2p3/2 at 851.2 eV and 780.2 eV respectively exhibited a shift to 850.9 eV and 779.7 eV (Fig. 4e and Fig. 4f)38,39,40,41, while W showed an increase in binding energy to higher values of 36.9 and 34.8 eV for the respective peaks of 4d5/2 and 4d7/2 (Fig. 4d). Similarly, Cr, Mn, and Fe in subnano-HELMO-PTA displayed a shift towards lower binding energy, indicating moderate reduction under illumination conditions (Fig. 4g, h, and i). On the contrary, there was no change observed in the characteristic peaks of HELMO/PTA after irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 22). This suggested that photo-excited electrons can be rapidly transferred from PTA to HELMO, resulting in an electron-rich HELMO species. These findings provided direct evidence for the direction of electron transfer within subnano-HELMO-PTA and indicate an interfacial electric field consistent with a (-p-n-p-n-)n type hetero-junction.

To investigate the mechanism of PEC conversion of CH4, in situ electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) was conducted using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as a spin-trapping agent. Figure 5a showed the EPR spectra of DMPO-·OH adducts of subnano-HELMO-PTA under lighting conditions, which exhibited typical quartet peaks with an intensity ratio of 1:2:2:142. Furthermore, the produced ·OH can be stabilized on the surface of subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst for up to 15 min due to the strong interaction between PTA and HELMO (Supplementary Fig. 23a). In contrast, pure PTA clusters exhibited weak stability under light irradiation, with a rapid decrease in ·OH amount as irradiation time was extended (Supplementary Fig. 23d). Upon introduction of CH4, both ·OH and ·CH3 were detected (Fig. 5a)43, indicating that the PEC conversion of CH4 over subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst was radical-based and involved the participation of ·CH3. Furthermore, it was noteworthy that as irradiation time increased, the concentration of ·OH decreased while that of ·CH3 increased (Supplementary Fig. 24a), providing evidence for the activation of adsorbed CH4 on subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst by produced ·OH. To provide additional evidence of the involvement of ·OH radicals in our system, CH4 oxidation reactions were conducted using the subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst in the presence of scavengers for ·OH radicals, namely ascorbic acid (AA) (Supplementary Fig. 25). In reactions where AA was included, there was a decrease in acetic acid productivity by 0.58 mmol g−1cat h−1 compared to 4.45 mmol g−1cat h−1 without scavengers. This observation suggests that PEC conversion of CH4 was facilitated by the presence of ·OH radicals.

a In situ EPR detection of ·OH and ·CH3 using DMPO as spin-trapping agent in the presence of subnano-HELMO-PTA as the catalyst. b In situ DRIFT spectra of photocatalytic CH4 oxidation over subnano-HELMO-PTA. c In situ Raman spectra of photocatalytic CH4 oxidation over subnano-HELMO-PTA. d Free energy diagrams for CH4 oxidation over the subnano-HELMO-PTA surface and HELMO (011) slab. The optimized structures of critical intermediates were also presented. e, Electron localization function maps of adsorbed COH on subnano-HELMO-PTA.

To further elucidate the mechanism of subnano-HELMO-PTA in OCM reaction, the reaction intermediates were monitored by in situ Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTs). It was worth noting that PEC conversion of CH4 was essentially a photocatalytic process, and the applied potential facilitated the transfer of photo-generated electrons16,18. Following the removal of physically adsorbed gases (such as H2O and CO2) from the catalyst surface, CH4 was introduced into the system. As depicted in Fig. 5b, two peaks located at 3014 and 1305 cm−1 attributed to adsorbed CH4 were progressively weakened with increasing irradiation time by a 405 nm LED light source from 0 to 15 min43, indicating continuous consumption of CH4. Meanwhile, multiple peaks emerged and their intensities gradually increased. The two novel peaks at 1132 and 965 cm−1 were assigned to the *CH3OH intermediate44, while the fresh band at 1265 cm−1 could be attributed to the characteristic mode of adsorbed *CHO species45. The vibration bands at 1345 and 1689 cm−1 were designated for the stretching vibration of carbonyl group in adsorbed *COOH species46. It was evident that *CH3OH and *CHO played crucial roles as intermediates in the oxidation process of CH4 to *COOH, which subsequently undergone a consecutive oxidative coupling reaction with *CH3 leading to acetic acid. Additionally, a peak at 2902 cm‒1 corresponding to the stretching vibration of C − H bond in the adsorbed *OCH3 species was also observed44. On the contrary, the asymmetry and symmetric extension vibration peaks of O − H bonds in H2O located at 3421 and 1625 cm−1 were observed to be continuously weakened under irradiation, indicating a continuous consumption of surface adsorbed H2O. Moreover, the intensity of peak at around 2300 cm−1 attributed to adsorbed CO2 remained unchanged47, indicating that no CO2 was generated during the photocatalytic reaction and thus no over-oxidation occurred in the resulting formic acid group. In comparison, HELMO subnanowires also exhibited the ability to convert CH4 into *COO (Supplementary Fig. 26). However, it became apparent that HELMO without PTA clusters presented in the sample could lead to overoxidation of products resulting in undesired CO2 due to the absence of critical catalytic sites required for stabilizing important intermediates. Furthermore, pure PTA clusters were susceptible to reduction and dissociation under lighting conditions (Supplementary Fig. 27). In order to investigate the high selectivity of C2 products (CH3CH2OH and CH3COOH) observed during PEC conversion of CH4 in this study, we conducted a novel in situ DRIFT experiment. As anticipated, if subnano-HELMO-PTA fails to effectively stabilize the *COOH intermediate, desorption of *COOH from the catalyst surface can be expected upon purging with Ar or steam (10%H2O/90%Ar). Upon introduction of Ar into the system, most of these intermediates exhibited sustained presence on the catalyst surface, as indicated by their persistent peak intensities (Supplementary Fig. 28). The adsorption peaks associated with these intermediates, particularly *CH3O at 965 cm−1, showed a decline upon introduction of 10% water vapor44,46,47, indicating its desorption from the catalyst surface due to the presence of water vapor. Interestingly, the adsorption peak related to the carbonyl group at 1705 cm−1 remained stable, suggesting that *COOH could persistently reside on the catalyst surface.

In situ Raman spectra were conducted to investigate the catalytic sites of subnano-HELMO-PTA for the OCM reaction. As depicted in Fig. 5c, the emergence of a Raman peak at 1613 cm−1, which was attributed to coupled C − C bonds48, was observed only when CH4 and an external light field were simultaneously introduced into the system. This characteristic peak was absent over nano-HELMO sample, revealing PTA provided the key sites for coupling of *CH3 and *COOH (Supplementary Fig. 29a). Furthermore, the in situ Raman spectra enabled us to identify a peak corresponding to W − C = O at 1369 cm−1 (ref. 49). It should be noted that no oxidizing agents (such as H2O2 or O2) were introduced into the system and any adsorbed H2O was removed by heating the subnano-HELMO-PTA under 90 oC prior to conducting in situ Raman tests. We hypothesized that the subnano-HELMO-PTA sample could activate CH4 to form CHx (1 ≤ x ≤ 4), which could then be captured and oxidized by O atoms (Ot or O2c) of PTA or chemically adsorbed H2O to form C = O stepwise. The resulting W carboxide species on the surface of PTA facilitated the subsequent coupling reaction. Finally, water served as the oxygen source to expel the products and occupy the oxygen vacancies on PTA, thereby refreshing the subnano-HELMO-PTA and closing the reaction. This was evidenced by the disappearance of both Raman peaks at 1369 and 1613 cm−1 upon introduction of steam. In order to decouple the mechanism of photocatalytic the electrocatalytic process, we conducted Raman spectroscopy analysis on the electrocatalytic methane oxidation over subnano-HELMO-PTA under dark conditions. The Raman peak corresponding to W − C = O at 1361 cm−1 was clearly observed (Supplementary Fig. 30)49, indicating the successful stabilization of the intermediates generated through CH4 activation on the PTA surface. However, the peaks corresponding to C − C bonds were notably attenuated compared to photocatalytic conditions, which could be attributed to insufficient production of hydroxyl radicals for methane coupling oxidation. Therefore, in conjunction with in situ tests conducted under diverse conditions, we can deduce the synergistic effect of the photocatalytic and electrocatalytic processes in the PEC reaction. Specifically, the electrocatalytic process not only enhances methane activation and polarization but also effectively segregates electron-hole pairs. Simultaneously, the hydroxyl radical generated by the photocatalytic process efficiently activates adsorbed methane to form highly active intermediates such as methyl groups, thereby facilitating subsequent reactions.

The PTM has been found to be capable of accepting electrons or holes from transition metal oxides20. The photocatalytic properties of subnano-HELMO-PTA can be enhanced by the p-n semiconductor hetero-junction through the introduction of PTA semiconductor with higher valence and conduction bands to HELMO. Moreover, it is crucial for these two phases to exhibit intimate contact50,51. Consequently, the core question about the PEC mechanism is the band structure of subnano-HELMO-PTA. Based on Kubelka-Munk transformation from UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectrum, the bandgap of HELMO and PTA were estimated to be 1.88 (Supplementary Fig. 31a) and 2.6 eV respectively (Supplementary Fig. 31b). The XPS valence bands in Supplementary Fig. 31c and Supplementary Fig. 31d were a relative value to the Fermi level, and the working function of equipment was 4.35 eV. Therefore, the valence band potential (Evв) was calculated to be −7.49 eV and −6.5 eV vs. vacuum level for HELMO and PTA respectively. Hence, the HELMO and the PTA possessed the VB maximum of 2.99 and 2 V vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) at pH 7, respectively. Therefore, the valence and conduction bands of PTA were found to be positioned at higher energy levels than those of HELMO, resulting in a greater electron flux from PTA onto HELMO (Supplementary Fig. 32a). With the aid of in situ experiments, we proposed that under irradiation and an external electric field, electrons were transferred to the conduction band of p-type semiconductor (HELMO) and subsequently moved to the cathode in the electrochemical system. (state 1 in Supplementary Fig. 32b). This hetero-junction enhanced the hole concentration in PTA. The HELMO site within the subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst, which exhibited enhanced charge accumulation under light irradiation, possessed a propensity to polarize CH4 molecules and attenuate their inert C − H bond strength, thereby facilitating the generation of reactive HELMO−CHx (1 ≤ x ≤ 4) intermediates (state 3 in Supplementary Fig. 32b). Meanwhile, H2O was oxidized by holes on PTA to ·OH (state 2 in Supplementary Fig. 32b). Subsequently, *CHx gradually dehydrogenated into a stabilized *COOH group with great assistance from PTA, which effectively inhibited over-oxidation to CO2 (state 4 in Supplementary Fig. 32b). The stabilized *COOH group participated in C − C coupling reaction with *CH3 and generated acetic acid as the final product (state 5 in Supplementary Fig. 32b). This result suggested that the C − C coupling process may be a kinetic process.

Density functional theory calculations

To shed light on the reaction mechanism of oxidative coupling of CH4, we performed DFT calculations on the subnano-HELMO-PTA (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 33, and Supplementary data 1), and the reaction paths of CH4 oxidation on HELMO (011) slab (Supplementary Fig. 34 and Supplementary data 1) was also computed for comparison. The energy profiles showed two rate-limiting steps: abstraction of H from CH4 and adsorbed hydroxymethyl. The calculation result suggested the dehydrogenation process from *CH3 to *CH2 on the HELMO surface was significantly endothermic with 1.01 eV. However, the formed *CH2 on subnano-HELMO-PTA was captured by terminal-O atom (Ot) in PTA with a barrier of 0.53 eV. Bader charges analysis and difference charge density plot in Supplementary Fig. 35a demonstrated a total of 0.22 |e| transferred from PTA to *CH2. Compared to the counterparts of HELMO surface (Supplementary Fig. 35b), of which the σ* orbital was shallowly enriched, it implied the adsorbed *CH2 was deeply activated on the surface of subnano-HELMO-PTA. Therefore, the energy barrier for the next dehydrogenation step from *OtCH2 (state IV in Fig. 5d) to *CHOt (state V in Fig. 5d) was dramatically decreased as compared with HELMO slab, 0.51 eV vs 0.71 eV. Interestingly, as the dehydrogenation reaction progressed, PTA can stably immobilize the key *OtCOH intermediate by providing 0.38 |e | . Specifically, as shown in the difference charge density in Supplementary Fig. 36a, the OtCOH π* received lot of electrons, which meant the *OtCOH was dramatically activated. On the contrary, this process was weakened on the pure surface of HELMO (Supplementary Fig. 36b). Besides, the computed projected density of state (PDOS) of the O atom in *OtCOH showed a similar electronic structure with Ot (Supplementary Fig. 37), which demonstrated Ot in PTA has become part of *OtCOH. As a result, it was hard for the *OtCOH intermediate to release as CO gas or overcome the energy barrier 1.84 eV, releasing as *OtCO gas by extracting *Ot in PTA (Fig. 5d).

Researchers paid little attention to electron-buffer-induced stabilizing, which usually plays an important role in heterogeneous catalysis. In order to investigate the characteristics of electron delocalization, we utilized XPS with a photon energy of 1.49 keV to analyze the valence band (VB) spectrum of subnano-HELMO-PTA. This technique provides atomic-level insights into the electronic structure of high entropy alloys (HEAs)52. The VB spectrum of subnano-HELMO-PTA, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 38a, exhibited an absence of distinct features unlike its PTA and nano-HELMO counterparts which displayed prominent peaks. This observation strongly indicates the loss of elemental identity in the atoms comprising subnano-HELMO-PTA. A similar “featureless” VB spectrum has been reported for RuRhPdAgOsIrPtAu HEAs53. Additionally, we elucidated the electronic structure of Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni elements within subnano-HELMO-PTA through DFT calculations. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 38b, all transition metals demonstrated a consistent trend and exhibited analogous electron distribution patterns in their local density of states (LDOSs), indicating delocalization of valence electrons among these transition metals53. Therefore, we have successfully demonstrated electron delocalization across subnano-HELMO-PTA using high-resolution XPS measurements and DFT calculations on LDOSs of transition metals.

To explore the above speculated electron-buffer-induced stabilizing mechanism, we calculated the PDOSs of O atoms of PTA. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 39a, O atoms in PTA except Ot presented almost the same electronic structure before the reaction. Their electronic structure changed to varying degrees at the time of adsorption of COH (Supplementary Fig. 39b), although these O atoms did not directly interact with *COH, which signified all O atoms attended the reaction and provided the acquired electrons of 0.38 |e| (Supplementary Fig. 36a). The phenomena revealed by DFT calculations can be conceptualized in the framework of electron state delocalization. In the subnano-HELMO-PTA surface, electrons on O atoms in PTA could move from one potential minimum to another and accumulate on adsorbed COH (Supplementary Note 4). Therefore, the electron delocalization-induced stabilization of adsorbates can be inferred from electron density distribution. Electron localization function in 2D plot (Fig. 5e) further revealed electron density of Ot was similar. As a result of electron delocalization-induced stabilization, *OtCOH was stabilized on the minimum points of the potential energy of surface (Supplementary Fig. 40). Besides, these minimum points were equivalent and adjacent, the confined *OtCOH can be easily coupled into C2 products with endothermic of only 0.58 eV (Supplementary Fig. 41). Therefore, through the implementation of design strategies, including in situ DRIFTS and XPS experiments as well as DFT calculations, we attributed the exceptional selectivity of subnano-HELMO-PTA towards acetic acid to its ability to stabilize crucial *COOH intermediates across subnano-HELMO-PTA, thereby effectively inhibiting their overoxidation.

By utilizing co-assembly of HELMO nuclei and PTA clusters, we successfully achieved the partial oxidation of CH4 to acetic acid with a productivity rate of 4.45 mmol g−1cat h_1 and a selectivity exceeding 99% through photoelectrochemical catalysis at room temperature and ambient pressure. We investigated the function of subnano HELMO and PTA clusters in activating CH4, as well as stabilizing crucial intermediates (*COOH), through in situ DRIFTs and Raman spectra analysis. Moreover, the proposed co-assembly strategy of cluster–nuclei not only demonstrated success in synthesizing subnanostructures but also provided strong interaction between HELMO and PTA clusters in the form of (-p-n-p-n-)n sub-1 nm heterojunction, which could prevent the decomposition of PTA under reaction conditions. Finally, the application of DFT calculations has revealed the mechanism of electron delocalization-induced stabilization through analysis of PDOSs and electronic density.

The oxidative coupling of CH4 to value-added chemicals under ambient conditions has been revisited by chemists for around two decades. However, photoelectrochemical catalysis is a nascent topic that holds great promise. We posit that several subnanostructured materials can be readily incorporated via this process.

Methods

Materials

Phosphotungstic acid hydrate (H3[P(W3O10)4]·xH2O, PTA), absolute ethanol (99.5%), n-hexane (99.5%) and cyclohexane (99.5%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd. Lanthanum nitrate hydrate (La(NO3)3·xH2O, > 95%), chromic nitrate hydrate (Cr(NO3)3·6H2O, > 95%), manganese nitrate hydrate (MnCl2, > 95%), ferric nitrate hydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, > 95%) cobalt nitrate hydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O) ( > 95%), and nickel nitrate hydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O) ( > 95%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, 98%) and oleylamine were purchased from Alfa Aesar Co., Ltd. 13CH4/Ar (10%/90% in v/v) was provided by Beijing Huanyu Jinghui capital gas Technology Co., LTD. All the chemicals were used as received.

Characterization

The X-ray diffraction patterns (XRD) were acquired via powder XRD using a Bruker D8-Focus X-ray diffractometer operating at 40 kV and 30 mA with Cu-Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) radiation, employing a scanning rate of 1° min−1. The morphology of subnano-HELMO-PTA and nano-HELMO was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, HITACHI H-7700) operating at 100 kV and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, JEOL JEM 2100 F) operating at 200 kV. Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectra (ICP-AES, Thermo IRIS Intrepid II) was employed to investigate composition of subnano-HELMO-PTA and nano-HELMO. The surface potential images of the samples were acquired via Kelvin probe force microscopy using a Pt/Ir coated Si tip on Cypher VRS (Oxford Instruments). The in situ AFM test process employed 405 nm light-emitting component. UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra were collected in the 200–1200 nm spectral range on a Shimadzu SolidSpec-3700 spectrophotometer with BaSO4 as reference.

Synthesis of subnano-HELMO-PTA

The subnano-HELMO-PTA was synthesized via a facile solvothermal approach. Initially, 0.05 mmol La(NO3)3·xH2O, 0.01 mmol Cr(NO3)3·6H2O, 0.01 mmol MnCl2, 0.01 mmol Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 0.01 mmol Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.01 mmol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O and 0.0196 g PTA were co-added into a 50 mL flask. Afterwards, 2 mL of absolute ethanol, 6 mL of n-hexane, and 1 mL of oleylamine were added to the mixture. The flask was then equipped with an allihn condenser and heated at a temperature of 100 °C for a duration of four hours while being stirred continuously for thirty minutes prior to the reaction. Following the reaction, the products were collected and washed with cyclohexane and ethanol before being centrifuged at a speed of 10000 rpm for ten minutes. This washing process was repeated three times in order to obtain the final product which could be dispersed in cyclohexane.

Synthesis of nano-HELMO

The preparation process of nano-HELMO was analogous to that of subnano-HELMO-PTA, except for the absence of PTA in the system. Specifically, 0.05 mmol La(NO3)3·xH2O, 0.01 mmol Cr(NO3)3·6H2O, 0.01 mmol MnCl2, 0.01 mmol Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 0.01 mmol Co(NO3)2·6H2O and 0.01 mmol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O were introduced into a 50 mL flask. Afterwards, 2 mL of absolute ethanol, 6 mL of n-hexane, and 1.9 mL of oleylamine were introduced into the mixture. Following a stirring period of 10 minutes, the flask was equipped with an allihn condenser and heated at a temperature of 100 °C for a duration of 4 h. Upon completion of the reaction process, the product was collected and subjected to washing with 10 mL cyclohexane and 10 mL ethanol before being centrifuged at a speed of 2000 × g for 10 min. This washing procedure was repeated three times in order to obtain the final ~0.46 g products which could be dispersed in cyclohexane.

Synthesis of subnano-LMO-PTA

The subnano-LMO-PTA was synthesized via a facile solvothermal approach. Initially, 0.05 mmol La(NO3)3·xH2O, 0.05 mmol MnCl2 and 0.0196 g PTA were co-added into a 50 mL flask. Afterwards, 2 mL of absolute ethanol, 6 mL of n-hexane, and 1 mL of oleylamine were added to the mixture. The flask was then equipped with an allihn condenser and heated at a temperature of 100 °C for a duration of 4 h while being stirred continuously for 30 min prior to the reaction. Following the reaction, the products were collected and washed with 10 mL cyclohexane and 10 mL ethanol before being centrifuged at a speed of 2000 × g for 10 min. This washing process was repeated three times in order to obtain the final ~0.1 g product which could be dispersed in cyclohexane.

Synthesis of subnano-MELMO-PTA

The subnano-MELMO-PTA was synthesized via a facile solvothermal approach. Initially, 0.05 mmol La(NO3)3·xH2O, 0.017 mmol Cr(NO3)3·6H2O, 0.017 mmol MnCl2, 0.017 mmol Co(NO3)2·6H2O and 0.0196 g PTA were co-added into a 50 mL flask. Afterwards, 2 mL of absolute ethanol, 6 mL of n-hexane, and 1 mL of oleylamine were added to the mixture. The flask was then equipped with an allihn condenser and heated at a temperature of 100 °C for a duration of four hours while being stirred continuously for 30 min prior to the reaction. Following the reaction, the products were collected and washed with 10 mL cyclohexane and 10 mL ethanol before being centrifuged at a speed of 2000 × g for 10 min. This washing process was repeated three times in order to obtain the final ~0.078 g product which could be dispersed in cyclohexane.

Synthesis of HELMO/PTA

According to the ICP-AES results, La and W elements exhibited almost identical contents with a mole ratio of 1:1.01. Subsequently, 1 mmol nano-HELMO and 1 mmol PTA were dispersed in a mixture of ethanol and water (v/v = 1/1) at a volume of 40 mL. The resulting mixture was subjected to ultrasonic dispersion and stirred for 30 minutes before being dried under conditions of 60 °C. Finally, the powder obtained was calcinated at temperatures reaching up to100 °C for 6 h.

Synthesis of HELMO with sol-gel method

The following metal precursors were added to a 250 mL beaker: 3.5 mmol La(NO3)3·xH2O, 0.7 mmol Cr(NO3)3·6H2O, 0.7 mmol MnCl2, 0.7 mmol Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 0.7 mmol Co(NO3)2·6H2O and 0.7 mmol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O. Subsequently, the mixture was dissolved by adding and stirring in 133.5 mL of water for 10 minutes. After that, a solution containing 3.5 mmol citric acid and 14 mmol glycol was added and stirred for another 10 min before being aged to form a gel at a temperature of 100 °C. Finally, the gel was calcinated at either 650 °C or 700 °C for a duration of 5 h.

Photoelectrochemical tests

PEC conversion of CH4 was investigated using an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660E) in a customized (500 mL), sealed H-type cell with Nafion 117 proton exchange membrane. A 300 W Xenon lamp provided by Beijing Perfect Light was utilized to simulate solar light, emitting wavelengths ranging from 320–780 nm and providing a power density of 100 mW cm−2. A mixture with a catalyst concentration of 1 mg/mL was prepared by dispersing 10 mg of catalysts, 10 mg of Vulcan XC-72 carbon, and 200 μL of Nafion (5 wt%) in 10 mL cyclohexane. Subsequently, the gas diffusion electrode (area: 1.4 cm × 1.4 cm) was uniformly coated with 1 mL ink (containing 1 mg catalyst) at room temperature. Thirdly, the gas diffusion electrode, Pt foil, and Ag/AgCl electrode were used as the working electrode, the counter electrode, and reference electrode, respectively. The photocurrent was recorded from 0.3 to 1.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl recorded at a scan rate of 5 mV/s in 0.5 M Na2CO3 without and with the CH4 gas purging for 60 min.

Synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was performed at the Ni-K edge (8339 eV) and Fe K-edge (7112 eV) using beamline BL11B of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), with a Si(111) double-crystal monochromator for beam tuning. Prior to analysis, samples were compressed into thin sheets measuring 1 cm in diameter and sealed with Kapton tape film. The X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) spectra were recorded at room temperature using a lytle fluorescence ionization chamber, calibrated according to the absorption edge of pure Ni or Fe foil. The storage ring had a typical energy of 2.5 GeV with a maximum current of 250 mA. Fluorescence mode was used to record Ni-K edge and Fe K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra, which showed negligible changes in line-shape and peak position between two scans taken for each sample. Data processing and analysis were conducted using Athena and Artemis software codes.

In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectra experiments

The Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer equipped with a mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector was utilized to conduct in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectra (DRIFTs). The in situ DRIFT spectra were acquired at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. After being pre-treated in N2 flow (20 mL/min) at 90 °C for 1 h, the sample underwent background spectrum collection prior to in situ DRIFTs experiments. The N2 flow was subsequently switched to a CH4 flow and maintained for 0.5 hours to achieve saturated adsorption of CH4. Following this, light with a wavelength of 405 nm was introduced, and the signal was recorded every minute.

In situ XPS experiments

The in situ XPS was conducted using the XPS Thermo Fisher 250i instrument. The radiation source employed was a laser from Williden Technology Co., Ltd. with a wavelength of 405 nm. The XPS photoelectron spectrum analysis was performed under complete darkness, followed by in situ irradiation for 15 min using the laser and subsequent re-analysis of the XPS photoelectron spectrum. Data processing and analysis were carried out using software associated with the XPS Thermo Fisher 250i.

In situ Raman experiments

For the photocatalysis, in situ Raman experiments were conducted using a Raman spectrometer (HORIBA Jobin Yvon Inc., Model: HR Evolution) equipped with an optical microscope. Prior to the reaction, a monocrystalline Si wafer was used for spectrometer calibration. The catalysts were then heated at 90 oC for 1 h to remove physically adsorbed H2O and CO2 from the surface. Subsequently, N2 and CH4 were introduced stepwise into the system. A near-infrared laser (λ = 785 nm) was employed as the excitation source while a laser with a wavelength of 405 nm was utilized.

For the electrocatalysis, a specially designed three-electrode cell was employed, featuring a platinum mesh counter electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and subnano-HELMO-PTA working electrode. The reactions took place at ambient temperature in 0.5 M aqueous Na2CO3 solutions saturated with CH4 gas. A near-infrared laser (λ = 785 nm) served as the excitation source, while utilizing a laser operating at a wavelength of 532 nm.

EPR tests for the detection of ·OH and ·CH3

In the PEC reaction system, 5, 5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) was utilized as a capture agent to trap the generated ·OH and ·CH3. The dried catalyst was first dispersed in cyclohexane with a concentration of 10 mg/mL. The catalyst was subsequently rinsed with ethanol and subjected to a drying process at 70 °C for 12 h, aiming to effectively eliminate the physically adsorbed oleylamine molecules on its surface. Subsequently, the resulting dry powder was ground in a mortar for 10 min. The resulting 4 mg catalyst and 2 mg Vulcan XC-72 carbon was deposited on gas diffusion electrode with area of 1.41 × 1.41 cm2. Then, 200 μL of Nafion (5 wt%) in 10 mL cyclohexane was deposited on the surface of gas diffusion electrode to fix the catalysts. The sealed H-type cell (50 mL) contained 40 mL 0.5 M Na2CO3 aqueous solution with DMSO at a concentration of 50 mg/mL. The air in reaction chamber was evacuated by introducing methane or Ar at a flow rate of 20 mL/min for a duration of 30 min. Then, the applied potential was set to be 1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). At last, the light (405 nm) was introduced and the solution inside the reaction tank was circulated to the chamber by a peristaltic pump (50 mL/min) for testing.

Mott–Schottky experiments

The nano-HELMO and PTA were dispersed ultrasonically in 10 mL of cyclohexane at a concentration of 1 mg/mL before being dropwise added onto three indium tin oxide substrates measuring 1 × 1 cm each. Mott–Schottky plots were obtained using a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation, with Ag/AgCl serving as the reference electrode and platinum wire mesh as the counter electrode. The samples, examined in a 1 M Na2SO4 solution, were tested at frequencies of 500, 800, and 1000 Hz.

EIS tests

The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were conducted at open circuit voltage (OCV) conditions, employing a potential amplitude of 5 mV and frequencies ranging from 105 to 1 Hz.

Product analysis

Gas products were analyzed using an online gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, GC-2014C) equipped with molecular sieve 5 A and propark Q packed column with argon as the carrier gas. Flame ionization detector (FID) and discharge ionization detector (DFID) were utilized for the examination of C1 compounds (CO, CO2 and CH4), C2 compounds (C2H2, C2H4, and C2H6), and C3 (C2H6, C3H4, and C3H6) respectively. The concentration of gas products was determined by calculating the peak areas from the gas chromatogram based on standard curves of pure samples.

The liquid products underwent qualitative and quantitative analysis using 1H NMR and 13C NMR (JEOL ECS-400 400 MHz NMR). Following electrocatalysis, the electrolyte was mixed with an internal standard consisting of 0.1 mL D2O and 0.05 μL DMSO in a volume of 0.5 mL. The resulting solution was subjected to water suppression during measurement of the 1H NMR.

The colorimetric method was utilized to determine the concentration of HCHO in liquid product. A reagent aqueous solution consisting of 15 g ammonium acetate, 0.3 mL acetic acid, and 0.2 mL pentane-2,4-dione dissolved in water was prepared first with a volume of 100 mL. Subsequently, a mixture containing 0.5 mL liquid product, 2.0 mL water and 0.5 mL reagent solution was subjected to UV−vis absorption spectroscopy51.

The selectivity of acetic acid was calculated as the following equation:

Selectivity = Yield of acetic acid/Conversion of methane

The conversion of CH4 (η) was presented as follow:

where C1 and C2 are molar concentration of CH4 in feeding gas and effluent stream, respectively.

Computational details

The Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) software package was utilized to perform spin-polarized DFT calculations using plane-wave pseudopotentials54,55,56. A kinetic energy cutoff of 450 eV was applied. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerh of (PBE) functional, based on the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) approach57, was employed to incorporate exchange and correlation energies. Core-valence interactions were represented using the PAW method58. The Monkhorst-Pack method was utilized to sample the Brillouin zone using a k-points grid of 1 × 1 × 1. To accurately consider the localized 3d orbitals of transition metals, spin-polarized DFT + U calculations were performed with Ueff values of 6.4, 6.5, 4.0, 4.0, and 3.3 for Ni, Cr, Fe, Mn, and Co respectively59,60. The atomic positions were relaxed until the force on each atom reached a convergence threshold below 0.01 eV/Å and electronic energies were converged within an accuracy of 10−4 eV. To adequately account for van der Waals (vdW) interactions, a technique incorporating Becke-Johnson damping function was employed61.

The LaMnO3 perovskite structure with a lattice parameter of 3.799 Å (optimized in the Pm3m space group) closely matched the experimental value of a0 = 3.808 Å62. The Special Quasirandom Structures (SQSs) for La(Cr0.2Mn0.2Fe0.2Co0.2Ni0.2)O3 were generated using the GENSQS module within the Alloy Theoretic Automated Toolkit (ATAT)63. To simulate the (110) surface of high-entropy LaMnO3-type perovskite terminated with LaMnO2, a primitive supercell of La(Cr0.2Mn0.2Fe0.2Co0.2Ni0.2)O3 was employed, and a six-layer slab was created by fixing the bottom three layers and relaxing the topmost ones accordingly while ensuring no interaction between replicated slabs in all dimensions through a 15 Å vacuum region.”

The subnano-HELMO-PTA structure was initially constructed based on the ICP-AES findings and our previous research. To prevent any interaction between the replicated slabs in three-dimensional space, a 15 Å vacuum was incorporated along the Z-axis. Throughout the optimization process of the initial slab, there were no restrictions imposed on atom positions, axis lengths, or box shape, except for the Z-axis.

Gibbs free energies for each gaseous and adsorbed species were calculated at 298.15 K, according to the following expressions:

where \(\Delta {{{\rm{E}}}}\) is the electronic energy difference between the free standing and adsorption states of reaction intermediates; \(\Delta {{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ZPE}}}}}\) and \(\Delta {{{\rm{S}}}}\) represent the changes in zero point energies and entropy, respectively, which are obtained from the vibrational frequency calculations51. In this work, the temperature (T) was set to be 298.15 K.

The values of \(\Delta {{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ZPE}}}}}\) and TS for each reaction intermediate can be calculated using the following equations.

where h is the Planck constant, \({{\sum }_{i}v}_{i}\) is cumulative value of the computed vibrational frequencies, R is the molar gas constant, \({\varTheta }_{i}\) is the characteristic temperature of vibration and could be calculated as \({\varTheta }_{i}\,=\,\frac{{{hv}}_{i}}{{k}_{B}}\), where \({k}_{B}\) is the Boltzmann constant51. For adsorbates, all 3 N degrees of freedom were treated as frustrated harmonic vibrations with negligible contributions from the catalysts’ surfaces.

The charge of system was treated in accordance with the widely-recognized computational hydrogen electrode model51, wherein each reaction step was considered as a simultaneous transfer of the proton-electron pair based on the applied potential. Consequently, alterations in free energy can be represented as follows.

For HELMO catalyst:

For subnano-HELMO-PTA catalyst:

The energy barrier of the reaction pathway was determined by evaluating the disparity in overall energy prior to and following the reaction. This assessment involved utilizing specific chemical equations, wherein * represented catalysts and Ot symbolized the terminal oxygen atom of PTA within subnano-HELMO-PTA. To calculate the energy of (H+ + e−), G[H+ + e‒] = 1/2 G [H2] – eU, where U denoted the applied overpotential and e represented the elementary charge64. For this particular study, U was set at 0 V compared to a reversible hydrogen electrode.

Potential energy surfaces play a crucial role in determining both the diffusion barrier and adsorption configuration. In this study, we focused on the most stable surface of the subnano-HELMO-PTA material. To construct the potential energy surface, discrete points were used with H atoms serving as detectors. Specifically, we gridded the surface and calculated the adsorption energy of H atoms on the lattice. Subsequently, contour maps were generated based on these adsorption energies. It is important to note that many of the initial adsorption sites proved to be unstable; therefore, we employed a strategy where we fixed the adsorbed molecules in their x and y directions while allowing relaxation in the z direction until achieving adsorption equilibrium.

Data availability

Source data of the characterizations of samples, catalytic performance, electrochemical measurements, and theoretical calculations for the main text are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Rost, C. et al. Entropy-stabilized oxides. Nat. Commun. 6, 8485 (2015).

Oses, C., Toher, C. & Curtarolo, S. High-entropy ceramics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 295–309 (2020).

Schweidler, S. et al. High-entropy materials for energy and electronic applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 266–281 (2024).

Sarkar, A. et al. High entropy oxides for reversible energy storage. Nat. Commun. 9, 3400 (2018).

Sarker, P. et al. High-entropy high-hardness metal carbides discovered by entropy descriptors. Nat. Commun. 9, 4980 (2018).

Aamlid, S. S., Oudah, M., & Rottler, J. et al. Understanding the role of entropy in high entropy oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5991–6006 (2023).

Jiang, B. et al. High-entropy-stabilized chalcogenides with high thermoelectric performance. Science 371, 830–834 (2021).

Manzoor, A. et al. Entropy contributions to phase stability in binary random solid solutions. npj Comput Mater. 4, 47 (2018).

Musicó, B. L. et al. The emergent field of high entropy oxides: design, prospects, challenges, and opportunities for tailoring material properties. APL Mater. 8, 040912 (2020).

Dragoe, N. & Bérardan, D. Order emerging from disorder. Science 366, 573–574 (2019).

Feng, G. et al. Sub-2 nm ultrasmall high-entropy alloy nanoparticles for extremely superior electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 17117–17127 (2021).

Hill, T. L. A different approach to nanothermodynamics. Nano Lett. 1, 273–275 (2001).

Schwach, P., Pan, X. & Bao, X. Direct conversion of methane to value-added chemicals over heterogeneous catalysts: challenges and prospects. Chem. Rev. 117, 8497–8520 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. Light-driven flow synthesis of acetic acid solely from methane with high selectivity by chemical looping in heterointerface nanocomposites. Nat. Commun. 14, 3047 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Photocatalytic conversion of methane: recent advancements and prospects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202108069 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Efficient photoelectrochemical conversion of methane into ethylene glycol by WO3 nanobar arrays. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9357–9361 (2021).

Wang, Q., Kan, M., Han, Q. & Zheng, G. Electrochemical methane conversion. Small Struct. 2, 2100037 (2021).

Mehmood, A., Chae, S. Y. & Park, E. D. Photoelectrochemical conversion of methane into value-added products. Catalysts 11, 1387 (2021).

Song, S. et al. A selective Au-ZnO/TiO2 hybrid photocatalyst for oxidative coupling of methane to ethane with dioxygen. Nat. Catal. 4, 1032–1042 (2021).

Yu, X. et al. Stoichiometric methane conversion to ethane using photochemical looping at ambient temperature. Nat. Energy 5, 511–519 (2020).

Li, X., Xie, J., Rao, H., Wang, C. & Tang, J. Platinum- and CuOx-Decorated TiO2 photocatalyst for oxidative coupling of methane to C2 hydrocarbons in a flow. React. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19702–19707 (2020).

Liu, Q. et al. Temperature-responsive self-assembly of single polyoxometalates clusters driven by hydrogen bonds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2103561 (2021).

Liu, Q. et al. Self-assembly of polyoxometalate clusters into two-dimensional clusterphene structures featuring hexagonal pores. Nat. Chem. 14, 433–440 (2022).

An, B. et al. Direct photo-oxidation of methane to methanol over a mono-iron hydroxyl site. Nat. Mater. 21, 932–938 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. H2-reduced phosphomolybdate promotes room-temperature aerobic oxidation of methane to methanol. Nat. Catal. 6, 895–905 (2023).

Nie, S., Wu, L. & Wang, X. Electron-delocalization-stabilized photoelectrocatalytic coupling of methane by NiO-polyoxometalate sub-1 nm heterostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 23681–23690 (2023).

Liu, J., Shi, W. & Wang, X. Cluster–nuclei coassembled into two-dimensional hybrid CuO-PMA Sub-1 nm nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 18754–18758 (2019).

Zhang, S. et al. Sub-nanometer nanobelts based on titanium dioxide/zirconium dioxide–polyoxometalate heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 33, 2100576 (2021).

Hwang, J. et al. Perovskites in catalysis and electrocatalysis. Science 358, 751–756 (2017).

Marschall, R. Semiconductor composites: strategies for enhancing charge carrier separation to improve photocatalytic activity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 2421–2440 (2014).

Liu, J. et al. Incorporation of clusters within inorganic materials through their addition during nucleation steps. Nat. Chem. 11, 839–845 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Au-Polyoxometalates A-B-A-B Type Copolymer-Analogue Sub-1 nm Nanowires. Small 17, 2006260 (2021).

Teja Nelabhotla, A. B., Bakke, R. & Dinamarca, C. Performance analysis of biocathode in bioelectrochemical CO2 reduction. Catalysts 9, 683 (2019).

Yao, Y. et al. Carbothermal shock synthesis of high-entropy-alloy nanoparticles. Science 359, 1489–1494 (2018).

Li, T. et al. Denary oxide nanoparticles as highly stable catalysts for methane combustion. Nat. Catal. 4, 62–70 (2021).

Liu, Q. et al. Single molecule–mediated assembly of polyoxometalate single-cluster rings and their three-dimensional superstructures. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax1081 (2019).

Liu, Q. et al. Visible light induced Ag–polyoxometalate coassembly into single-cluster nanowires. Adv. Mater. 34, 2206178 (2022).

Song, H. et al. Atomically dispersed nickel anchoredona nitrogen-doped carbon/TiO2 composite for efficient and selective photocatalytic CH4 oxidationto oxygenates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202215057 (2023).

Lustemberg, P. G. et al. Direct conversion of methane to methanol on Ni-Ceria surfaces: metal–support interactions and water-enabled catalytic conversion by site blocking. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7681–7687 (2018).

Yang, H., Yang, D. & Wang, X. POM-incorporated CoO nanowires for enhanced photocatalytic syngas production from CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15527–15531 (2020).

Wurster, B. et al. Driving the oxygen evolution reaction by nonlinear cooperativity in bimetallic coordination catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3623–3626 (2016).

Luo, L. et al. Binary Au−Cu reaction sites decorated ZnO for selective methane oxidation to C1 oxygenates with nearly 100% selectivity at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 740–750 (2022).

Zhu, S. et al. Efficient photooxidation of methane to liquid oxygenates over ZnO nanosheets at atmospheric pressure and near room temperature. Nano Lett. 21, 4122–4128 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. Elevating photooxidation of methane to formaldehyde via TiO2 crystal phase engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15977–15987 (2022).

Zheng, K. et al. Room-temperature photooxidation of CH4 to CH3OH with nearly 100% selectivity over hetero-ZnO/Fe2O3 porous nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12357–12366 (2022).

Zheng, K. et al. Selective CH4 partial photooxidation by positively charged metal clusters anchored on carbon aerogel under mild conditions. Nano Lett. 21, 10368–10376 (2021).

Jiang, W. et al. Pd-modified ZnO−Au enabling alkoxy intermediates formation and dehydrogenation for photocatalytic conversion of methane to ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 269–278 (2021).

Devasia, D. et al. A rich catalog of C–C bonded species formed in CO2 reduction on a plasmonic photocatalyst. Nat. Commun. 12, 2612 (2021).

Sato, E. T. & Martinho, H. First-principles calculations of Raman vibrational modes in the fingerprint region for connective tissue. Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 1728–1734 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhanced full-spectrum photocatalytic activity of 3D carbon-coated C3N4 nanowires via giant interfacial electric field. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 318, 121829 (2022).

Song, H. et al. Direct and selective photocatalytic oxidation of CH4 to oxygenates with O2 on cocatalysts/ZnO at room temperature in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20507–20515 (2019).

Wu, D. et al. On the electronic structure and hydrogen evolution reaction activity of platinum group metal-based high entropy-alloy nanoparticle. Chem. Sci. 11, 12731–12736 (2020).

Wu, D. et al. Platinum-group-metal high-entropy-alloy nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13833–13838 (2020).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 1759 (1999).

Bengone, O., Alouani, M., Blochl, P. & Hugel, J. Implementation of the projector augmented-wave LDA+U method: application to the electronic structure of NiO. Phys. Rev. B. 62, 16392 (2000).

Zhang, L., Su, Y., Chang, M., Filot, I. & Hensen, E. Linear activation energy-reaction energy relations for LaBO3 (B = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni) supported single-atom platinum group metal catalysts for CO oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 31130–31141 (2019).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456 (2011).

Estemirova, S. K., Yankin, A. M., Titova, S. G., Balakirev, V. F. & Turkhan, Y. E. Phase composition and structure of La1-xCaxMnO3+δ (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.2) solid solutions. Inorg. Mater. 44, 1387–1392 (2008).

Walle, A. Multicomponent multisublattice alloys, nonconurational entropy and other additions to the alloy theoretic automated toolkit. Calphad 33, 266–278 (2009).

Peterson, A. A. et al. How copper catalyzes the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1311 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Haifang Li and Haiming Wu for help with product analysis, Shufang Yue for the help with in situ AFM, Jianxia Duan and Wenqing Yao for help with in situ XPS, and Haijun Yang and Wenyu Li for the help with in situ EPR, respectively. This work was supported by NSFC project (Grant No: 22241502, 22035004, 22305137, and 22250710677) and the XPLORER PRIZE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N. investigated the literature, carried out the experiments, conducted DFT calculations, and wrote this manuscript. L.W. supervised the parts of DFT calculations in this work. Q.Z. performed the atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM tests. Yunwei Huang carried out the tests of TEM over subnano-HELMO-PTA. Q.L. and X.W. conceived, supervised, and reviewed this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alessandro Tofoni, who co-reviewed with Paola D’Angelo, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nie, S., Wu, L., Zhang, Q. et al. High-entropy-perovskite subnanowires for photoelectrocatalytic coupling of methane to acetic acid. Nat Commun 15, 6669 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50977-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50977-8

This article is cited by

-

Orchestrated multi-physics field-engineering toward valorized C2+ chemicals from CO2/CH4

Science China Materials (2026)

-

Coordination-tailored atomic interfaces for selective CH4-to-C2 conversion in aqueous solution

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Conversion of methane to C2 liquid oxygenates by Ru atom arrays

Nature Communications (2025)

-

High-entropy alloys go subnanoscale: novel synthesis and enhanced electrocatalysis for water splitting

Science China Materials (2025)