Abstract

The separation and purification of chemical raw materials, particularly neutral compounds with similar physical and chemical properties, represents an ongoing challenge. In this study, we introduce a class of water-soluble macrocycle compound, calix[2]azolium[2]benzimidazolone (H), comprising two azolium and two benzimidazolone subunits. The heterocycle subunits form a hydrophobic binding pocket that enables H1 to encapsulate a series of neutral guests in water with 1:1 or 2:1 stoichiometry, including aldehydes, ketones, and nitrile compounds. The host-guest complexation in the solid state was further confirmed through X-ray crystallography. Remarkably, H1 was shown to be a nonporous adaptive crystal material to separate valeraldehyde from the mixture of valeraldehyde/2-methylbutanal/pentanol with high selectivity and recyclability in the solid states. This work not only demonstrates that azolium-based macrocycles are promising candidates for the encapsulation of organic molecules but also shows the potential application in separation science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Proteins exhibit a notable capacity for binding neutral organic molecules attributed to their hydrophobic binding pockets equipped with converging polar and charged groups in aqueous solutions1,2,3. Inspired by this, synthetic macrocyclic hosts4,5,6,7,8,9, including crown ether10, cyclodextrin11,12, calixarene13,14,15, pillararene16,17,18,19, cucurbituril20,21,22, corona[n]arene23,24, and others25,26,27,28,29,30,31, which aim to mimic the remarkable properties of biological hosts have attracted a great deal of research attention. Despite significant progress in this field over the past decades, the development of readily accessible and water-soluble macrocyclic compounds with precisely defined cavities and tailored host–guest properties remains a formidable challenge14,32,33,34,35,36,37. Moreover, while substantial progress has been made, there still remains a gap in understanding the molecular recognition mechanisms at the molecular level, which is crucial for elucidating structure-property relationships.

Cationic macrocyclic hosts have been widely used in host–guest chemistry and material science due to their inherent advantages, such as rigid cavities, excellent electron-deficient properties, and favorable redox characteristics6,38. A prominent example is cyclobis-(paraquant-p-phenylene), commonly referred to as the blue box39. Among them, imidazolium-based cationic macrocycles are privileged instances adept at binding anionic substrates via electrostatic interactions40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Moreover, they serve as precursors to imidazolylidenes (N-heterocyclic carbenes)47. However, their limited ability to recognize neutral molecules makes it far from anticipated separation applications. Unlike anions, achieving selective recognition of neutral molecules requires favorable interactions, such as hydrophobic effects and non-covalent interactions, in conjunction with a well-defined cavity48,49,50. Bridging of functional groups in the macrocycle presents an effective modification strategy14,34. This approach can endow a widened deep intramolecular cavity and augment multiple non-covalent interactions, thereby enhancing binding affinity and selectivity.

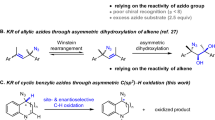

In this work, a class of macrocyclic hosts, termed calix[2]azolium[2]benzimidazolone (H), is designed and synthesized (Fig. 1). H comprises azolium and benzimidazolone subunits bridged by methylene groups, which combine the advantages of facile synthesis, high yield of preparation, well-defined structure, and crystal-state host–guest properties. The incorporation of benzimidazolone units into H results in a deep container open at one end and equipped with polar groups at the closed end. This design feature enables H to recognize electron-rich molecules (such as aldehydes, ketones, and nitriles) in water and form 1:1 and 2:1 stoichiometries host–guest complexes through multiple driving forces in a cooperative manner. Leveraging the superior solubility and crystallinity of H, single crystals of these host–guest complexes can be obtained, facilitating further exploration of complexation between H and guests at the molecular level in the solid state. Moreover, we present the fabrication of nonporous adaptive crystals (H1α) based on H1 (calix[2]imidazolium[2]benzimidazolone)18. H1α exhibits the capability to separate valeraldehyde from 2-methylbutanal and cyclopentanone from cyclopentanol with high purity levels of 99.2% and 99.9%, respectively, through a straightforward solid-liquid phase adsorption process. Additionally, H1α can be easily recycled by removing the trapped guests, transforming the absorbed H1α crystals to their original guest-free form. This recycling property of H1α renders it an excellent option for separation applications.

a The synthetic route of water-soluble macrocycle calix[2]azolium[2]benzimidazolones. b–e Chemical structures of H1–H4. f–i Side views of the solid-state structures of H1–H4 obtained from single crystal X-ray diffraction analyses. j–m Top views of the solid-state structures of H1–H4 obtained from single crystal X-ray diffraction analyses. Color codes: carbon, gray; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; hydrogen, white.

Results

Macrocycle design, synthesis, and characterization

The design of these H macrocycles is depicted in Fig. 1a. Initially, the benzimidazolone motif 1, 1,3-bis(chloromethyl)−1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-one, was readily obtained through modifications of the inexpensive and commercially available 2-hydroxybenzimidazole (Supplementary Figs. 1–4). Subsequent reactions with imidazole derivatives yielded C-shaped clefts 2 functionalized with different imidazoles. The final fragment cyclization of 2 with benzimidazolone motif 1 under refluxing in acetonitrile for 5 h provided the crude product of H (H = H1-H4) with Clˉ as counterions (Fig. 1b–e). Following crystallization in methanol, pure H was obtained with isolated yields ranging from 55% to 72% in 100 g batches. All four calix[2]azolium[2]benzimidazolones exhibited solubility exceeding 10 mM in water due to their cationic nature.

The synthesized macrocycles H1-H4 were characterized by high-resolution mass spectrum (HRMS), 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and single crystal X-ray analysis (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figs. 5–17). These analyses provided strong evidence for the molecular formulae of H1-H4. The 1H NMR spectra of H1-H4 recorded in D2O revealed only one set of sharp resonances, indicative of their highly symmetrical structures. The introduction of sterically hindered benzimidazolone resulted in the suppression of azolium rings flipping45,51, leading to the conformational immobilization of H. In all four cases, the resonance corresponding to the N-CH-N proton of azolium units became invisible in the 1H NMR spectra recorded in D2O, presumably due to the exchange between active hydrogen and deuterium in D2O (H/D exchange)52,53,54. When these exchange processes occurred at a medium rate on the 1H NMR timescale, N-CH-N resonances broadened into the baseline. Notably, the 1H NMR spectra of millimolar D2O solutions of free H1-H4 exhibited sharp proton signals owing to their rigidity. Moreover, the aromatic cavities of H could be further modified by introducing substituents at their upper rims, yielding calix[2]azolium[2]benzimidazolones H5-H7 functionalized with arenes, amides, and esters chains (Supplementary Figs. 18-22).

Macrocycle crystal structure

H exhibits favorable crystallization properties, yielding single crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments through slow vapor diffusion of i-Pr2O into a mixture of H2O and MeOH of H at room temperature. As depicted in Fig. 1, H1-H4 are constructed from four connected N-heterocycle cores by covalent attachment of walls, resulting in one open end and one bottom plane consisting of two O and two H coordination sites. H adopts a symmetrical vase-shaped conformation with different distances between the upper and lower rims ranging from 9.92 to 11.40 Å and 3.14 to 3.38 Å (Fig. 1f–m), respectively. In addition to the two imidazolium walls, the inclusion of benzimidazolone scaffolds provides a four-wall container H1 with a deep intramolecular cavity (5.74 Å). Further substitution of benzimidazolium derivatives in each imidazolium group yields the four-wall aryl-extended macrocycles H2-H4 (5.87, 7.14, and 7.36 Å in height, respectively). The pairs of azlolium and benzimidazolone units in H1-H4 are arranged pseudo-face-to-face. Considering the plane established by the methylene bridges, two benzimidazolone units point in the same direction, resulting in torsion angles of approximately 58.1˚, 77.2˚, 76.4˚, and 76.1˚ for H1-H4 (Supplementary Fig. 24). Accordingly, the dihedral angles of two azolium units are approximately 68.4˚, 43.2˚, 39.8˚, and 40.9˚ in H1-H4, while possessing similar corner angles of about 110˚. The net result is the formation of a confined cavity with a hydrophobic upper rim and a relatively hydrophilic lower rim simultaneously. The cavities of H1-H4 are electron-deficient and hydrophobic in water, defined by two azolium and two bezimidazolone units, thereby serving as binding pockets for selectively binding electron-rich guests with high affinities. Herein, a series of aldehydes, ketones, and nitriles (G1-G29) were tested as guests (Fig. 2).

In the packing diagram, one benzimidazolone subunit is partially located inside the cavity of an adjacent H1, stabilized by C-H···π interactions, while arranged parallel and opposite to another adjacent H1 through π···π interactions (Supplementary Fig. 25), resembling the arrangement observed in H3 in the solid state (Supplementary Fig. 27). In contrast, H2 acts as a linker between two adjacent H2 in the pseudo-head-to-head and tail-to-tail modes, respectively, connecting the components within a two-dimensional (2D) plane to form lamellar superstructures based on multiple C-H···π and C-H···O interactions (Supplementary Fig. 26). H4 stacks in an opposite orientation directed by C-H···O and π···π interactions (Supplementary Fig. 28).

Guest inclusion studies

The complexation of the macrocycle H with butyraldehyde (G2) was investigated in the solid state. X-ray crystallography revealed the formation of G2@H host–guest complexes (Fig. 3), facilitated by their inherent characteristics of preorganized cavities and multiple non-covalent binding sites. In all complexes, each G2 molecule is situated within the cavity of H by lone pair···π and C−H···π interactions55. H1-H4 behave as electron-deficient macrocyclic hosts, accommodating aldehydes within their vase cavities composed of two azolium heterocycles and two benzimidazolone rings.

a–d Top: top views of the single crystal structures of G2@H1, G2@H2, G2@H3, and G2@H4. Hydrogen atoms of H are omitted for viewing clarity. Blue dotted lines indicate lone pair···π interactions. Black dotted lines indicate C−H···π interactions. Red dotted lines indicate C−H···O interactions. Middle and bottom: side views of the single crystal structures of G2@H1, G2@H2, G2@H3, and G2@H4 (from left to right). Hydrogen atoms of H are omitted for viewing clarity. The arrows represent distances of the rims of H. P1–P4 represent the planes of N-heterocycles, and the relevant dihedral angles are illustrated.

Several noteworthy structural features were observed. First, G2 forms typical lone pair−π interactions with all four N-heterocycles, evidenced by the short distances between G2 to the centroid or plane of the N-heterocycles. For example, the oxygen atom of G2 in the G2@H1 and G2@H2 complexes exhibited distances ranging from 3.11 to 3.27 Å to the centroid of azolium rings (Fig. 3a, b, top). G2@H3 complex displayed the shortest contact with imidazolium rings, with distances of 3.03 and 3.06 Å, owing to the incorporation of 5,6-dimethyl benzimidazolium units (Fig. 3c, top). In contrast, in the G2@H4 complex, the oxygen atom of G2 is located inside the cavity, resulting in longer distances to the centroid of imidazolium rings as 3.59 and 3.64 Å (Fig. 3d, top). Second, G2 interacts with two benzimidazolone rings through lone pair−π interactions in G2@H complexes. G2@H1, G2@H2, and G2@H3 exhibit comparable lone pair−π interactions in the range of 3.07 to 3.26 Å, while G2@H4 displays relatively weaker interactions at approximately 3.64 and 4.05 Å (Fig. 3a–d, top). Third, in addition to the lone pair−π interactions mentioned above, G2 is bonded inside the cavity of macrocycle H through multiple C–H···π interactions between the hydrogen atoms of G2 and the aromatic rings of H. Notably, H2 and H3 form stronger C–H···π interactions with G2 than H1 due to the presence of benzimidazolium units, evidenced by the short distances (2.89 and 2.99 Å) between alkyl C–H of G2 and aromatic rings of the host. Furthermore, the cavity size of the host in each complex, defined by the lower rim distance between two azolium rings, increased compared to that of the parent macrocycles H1-H4 (Fig. 3a–d, middle). In G2@H4, a significant decrease in the dihedral angle of two azolium rings was observed due to the additional formation of C–H···O interactions. Lastly, the lower rim distances between two benzimidazolone rings slightly decreased (Fig. 3a–d, bottom), while the dihedral angle of two benzimidazolone rings increased, with values ranging from 45.7˚ to 76.5˚.

Based on the above results, we investigated the binding ability of H1 to a series of monofunctional aldehydes (Fig. 2, G1-G13). Specifically, the proton of the aldehyde group was selected to investigate the host–guest interactions in water. In the presence of H1, all proton resonances corresponding to the aldehyde groups of G1-G13 exhibited distinct upfield shifts, indicating the formation of host−guest complexes (Supplementary Figs. 31–43). Among these complexes, large upfield shifts of the proton signals belonging to the aldehyde groups were observed in the NMR spectra of G1-G5 when H1 was introduced into water: shifts of −0.82, −0.91, −1.19, −1.90, and −1.84 ppm for G1-G5, respectively, as the alkyl chain increased. This shielding effect is expected as four N-heterocycle panels surround the aldehyde within the cavity. Considering the transformation from G1-G6 to the relevant gem-diol form in water56, G7 was selected for detailed investigation to elucidate the binding mode and interactions between host and guest in water (Fig. 4a). Upon addition of H1, all proton signals of G7 shifted upfield relative to the free guest (Fig. 4c, d, ∆δ = −0.75, −0.69, −0.22, and −0.14 ppm for protons 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively). This shift indicates that G7 was encapsulated within the cavity of H1, consistent with the results obtained from the host–guest single-crystal analysis. Additionally, the proton signals of host H1 exhibited slight upfield shifts after complexation (Fig. 4b, c). During the titration experiment, fast exchange kinetics on the 1H NMR timescale was observed, and a 1:1 binding stoichiometry of G7@H1 was inferred from Job plot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 37).

a Schematic presentation of the host–guest complexation between H1 and G7 and the top and side views of the single crystal structure of G7@H1. b 1H NMR spectrum (298 K, 400 MHz, D2O) of H1. c 1H NMR spectrum (298 K, 400 MHz, D2O) of H1 after adding 1.0 equiv. of guest G7. d 1H NMR spectrum (298 K, 400 MHz, D2O) of free guest G7. The concentrations of H1 and G7 were kept constant (i.e., 1.0 mM) in all the spectra.

By performing isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments, the binding constant (Ka) values for aldehydes in water are determined (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 49–53). Even though all these seven aliphatic aldehydes G1-G7 can fit in the cavity of H1, G3 emerges as the superior guest. Among the seven monoaldehyde guests, G3 exhibits the largest Ka (3370 ± 233 M−1), which is one order of magnitude higher than that of G4. The binding data for G1, G2, and G5 are too weak to be obtained, consistent with our previous observations of the proton shift.

To elucidate the host–guest interactions at the molecular level, we crystallized the guest-loaded single crystals to explore the effect between H1 and the aldehyde guests. As depicted in Fig. 5, each guest is located within the cavity of H1 via lone pair···π and C−H···π interactions. The aldehyde groups are positioned at the bottom of the cavity through lone pair···π interactions, while the aliphatic chains extend to the upper rim in an extended conformation through multiple C−H···π interactions. Notably, a folded chain at the end of G5 is observed in G5@H1 due to the formation of a C−H···π interaction between a fixed methylene and another H1 outside the upper rim of the cavity (Supplementary Fig. 68)34. Considering the binding constants determined by ITC experiments, we confirmed that minor structural differences significantly influenced the binding affinities of H1. Compared to free H1, the upper-rim distance between two benzimidazolone rings increases in the order of 8.24 Å (G2@H1), 8.35 Å (G3@H1), and 8.41 Å (G4@H1), indicating cavity contraction due to multiple host–guest interactions (Supplementary Fig. 70). Additionally, the dihedral angle of the two rings slightly decreases from 45.7˚ (G2@H1) to 46.8˚ (G3@H1) to 47.6˚ (G4@H1). The variations in the shape and size of host H1 formed by two pairs of opposing rings substantiate the fine- and self-tunability of the cavity. Aromatic aldehydes, including benzaldehyde, cinnamyl aldehyde, and 2-furyl acrolein, can also be complex with the host H1.

The binding affinity, however, was not limited to aldehydes: ketones and nitriles are also complexed by H1 in water. However, there was no evidence of guest recognition when equivalent amounts of alcohol, acid, and alkyne are added under the same conditions. Four-, five-, and six-membered cyclic ketones (G16-G18) formed 1:1 host–guest complexes with H1 in water, as confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy and single crystal X-ray analysis (Supplementary Figs. 44–48, 71). In addition to lone pair−π interactions and C-H···π interactions, C−H···N hydrogen bonding interactions also supported the complexation between nitriles and H1 within the range of 3.09–3.48 Å (Supplementary Fig. 72). A series of linear, branched chain, and even cyclic nitriles (G19-G28) could be accommodated in the cavity of H1 to form 1:1 host–guest complexes (Supplementary Figs. 54–63, 73–86).

The stoichiometry of the host–guest complexes also depended on the number of polar groups and the length of aliphatic chains. While the rim atoms of H1 exhibited little self-complementarity, the ditopic guests appeared to induce the formation of a capsule, resulting in 2:1 host–guest complexes. For aldehydes, the extended capsule could be formed from H1 and glutaraldehyde or adipaldehyde guests (G14, G15) through multiple lone pair−π interactions, C-H···π interactions, and hydrophobic effects (Fig. 6a, b). Nitriles up to glutaronitrile (G25-G28) resulted in 1:1 host–guest complexes, whereas longer adiponitrile (G29) formed a 2:1 complex in which G29 was incarcerated inside the capsule in an extended conformation in water (Fig. 6c).

Separation of valeraldehyde by nonporous adaptive crystals H1α

Valeraldehyde holds significant importance as a key feedstock chemical in the chemical industry, finding applications in fragrance production, resin chemistry, and rubber accelerators. Typically, valeraldehyde is industrially synthesized through the hydroformylation of 1-butene in the presence of a catalyst57. However, this reaction inevitably yields a mixture of isomeric products, including valeraldehyde (G3, linear), 2-methylbutanal (MB, branched), and pentanol (PA), necessitating further purification through energy-consuming and environmentally unfriendly distillation processes (Fig. 7a)58,59,60.

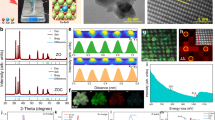

a Schematic representation of hydroformylation of 1-butene. b PXRD patterns of (I) original H1α; (II) H1α after uptake of G3 liquid; (III) H1α after uptake of G3/MB mixture (1:1, v/v); (IV) H1α after uptake of G3/PA mixture (1:1, v/v); (V) H1α after uptake of G3/MB/PA mixture (1:1:1, v/v/v). c Relative contents of G3 and MB adsorbed in H1α measured by gas chromatography. d Relative contents of G3, MB, and PA adsorbed in H1α measured by gas chromatography. e Recycling performance of H1α.

Preliminary results suggested that H1 exhibited selective recognition toward aldehydes, enabling the discriminating and selective separation/absorption of target valeraldehyde from a mixture with MB and PA. In this regard, we explore its potential use as an adsorptive separation material. Activated guest-free H1 crystals, named H1α, were obtained by heating at 60 ˚C under 0.1 torr for 12 h to remove CH3OH from the crystals. 1H NMR and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) affirmed the complete removal of CH3OH (Supplementary Figs. 87, 88). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data suggested that the obtained H1α powder was crystalline and different from its CH3OH-containing crystals H1 (Supplementary Fig. 89), further confirming the crystal transformation induced by solvent removal. The 77 K N2 sorption test indicated the nonporous nature of H1α (Supplementary Fig. 90) and dense packing in its crystal state.

Despite its nonporous feature, TGA and NMR data confirmed the effective adsorption capability of H1α toward G3 through a solid-liquid adsorption process, with the uptake amount of G3 calculated to be 0.8 molecule per H1α (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Figs. 91, 97). It is noteworthy that the transformation from G3 to the relevant gem-diol form in water can be suppressed upon the formation of G3@H1α crystals, with no signals corresponding to the gem-diol form detected in the 1H NMR spectrum of G3@H1α crystals in D2O solution. On the other hand, PXRD studies were conducted to investigate the crystalline phase changes upon guest uptake (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Figs. 93, 95). The PXRD patterns changed after the adsorption of G3, indicating a structural transition from the guest-free H1α crystals to the G3-loaded crystalline structure. Based on the FTIR spectra, a new peak at 1665 cm−1, representing the carbonyl stretching vibration absorption peak of G3, appeared upon G3 adsorption (Supplementary Fig. 96), further validating the adsorption capability of H1α. These findings made H1α a potential sorbent material with aldehyde selectivity.

The sorbent ability of H1α was further investigated by taking up G3 from mixtures of G3/MB and G3/PA (1:1, v/v), respectively. H1α selectively adsorbed G3, while the uptake of MB and PA was minimal (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 98, 99). Gas chromatography (GC) data revealed high selectivity for G3 during these solid-liquid phase adsorption processes (96.5 and 99.1% in the G3/MB and G3/PA mixtures, respectively. Supplementary Figs. 100, 101). Furthermore, the purity of G3 absorbed in H1α reached 99.2% when mimicking a more realistic ratio of G3/MB (97:3, v/v) in the crude product after butene hydroformylation (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 102)57. Inspired by the above results, solid-liquid phase adsorption was conducted in a three-component mixture of G3/MB/PA (1:1:1, v/v/v). As expected, H1α demonstrated high selectivity towards G3 as determined by GC experiments (97.5%, Fig. 7d and Supplementary Fig. 103). Moreover, after the solid-liquid phase adsorption of this three-component mixture, the removal of guest from the G3-loaded crystals under reduced pressure and heating could lead to the recovery of the original guest-free H1α, which can be recycled 4 times without any material decomposition or performance loss (Fig. 7e, Supplementary Note 4, and Supplementary Figs. 104, 105). PXRD patterns of H1α after adsorption of equal volume mixtures of G3/MB, G3/PA, and G3/MB/PA all matched well with G3@H1 (Fig. 7b), confirming the excellent anti-interference capabilities of H1α in the purification of G3 molecules.

Considering the close boiling points of cyclopentanone (G17) and cyclopentanol (CPOL), which are typically obtained as mixtures during industrial preparation, we further applied H1α in discriminating G17 and CPOL (Fig. 8)61. Upon solid-liquid phase adsorption, G17 could be separated from the G17 and CPOL mixture (1:1, v/v) with remarkably high purity (99.9%, Supplementary Figs. 106–110). H1α proved to be a powerful and practical adsorbent material due to its simple operation, high efficiency, and recyclability.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have successfully designed and synthesized a series of water-soluble calix[2]azolium[2]benzimidazolone H. The incorporation of benzimidazolone units into H provides four aromatic walls and a deepened cavity, enhancing the binding properties and adaptability of the macrocycles. Consequently, H1 exhibits promising potential as an adsorbent capable of selectively recognizing aldehyde and nitrile guests in both solid and aqueous solutions through C−H···π and lone pair···π interactions. Single-crystal diffraction experiments have revealed that the selectivity originates from the robust host–guest interactions between the target guest and H. Additionally, nonporous adaptive crystals H1α demonstrate high selectivity toward G3 and G17 with good recyclability without any loss of performance. Future research efforts will focus on exploring nonporous adaptive crystals to achieve the recognition and separation of functional molecules. We anticipate that the design of azolium-based macrocycles and further investigation into their binding properties will pave the way for promising applications in many research areas, including supramolecular catalysis, chemical biology, and materials science.

Methods

Full experimental details and characterization of compounds can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Materials and instrumentation

All starting reagents and solvents were used as commercially available without further purification unless otherwise noted. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were measured on Bruker AVANCE III 400 and JEOL 400 spectrometer with 1H chemical shifts quoted in ppm relative to the signals of the residual non-deuterated solvents or 0.0 ppm for tetramethyl silane (TMS). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out on a TA Instruments Q500 thermogravimetric analyzer. Samples were heated under a nitrogen atmosphere from room temperature to 500 ˚C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The data were prepared using the TA Instruments Universal Analysis software. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) experiments were carried out on a Bruker D2 Phaser desktop diffractometer equipped with a LYNXEYE detector. Intensity data were recorded in the 2θ° range 5–45° with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å). Gas chromatography (GC) analyses were carried out on an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector. The column used was an HP INNOWAX (cross-linked polyethylene glycol) column with dimensions 30 m × 0.25 mm and a film thickness of 1 µm. HRESI-TOF mass spectra were recorded on Bruker microTOF-Q II mass spectrometer. Bruker Data Analysis software and the simulations were performed on Bruker Isotope Pattern software. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was carried out in an aqueous solution using a VP-ITC (Malvern) at 25 ˚C, and computer fitting of the data were performed using the VP-ITC analyze software.

Single-crystal X-ray crystallography

All single crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer, using graphite monochromated Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). The crystal structure was solved and refined against all F2 values using the SHELX (version 2018/3) and Olex 2 (version 1.2) suite of programs. The detailed experimental parameters are summarized in Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Tables 2–31.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Information. The X-ray crystallographic files for structures in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC: 2331045 (H1); 2331277 (H2); 2331278 (H3); 2331283 (H4); 2333761 (H5); 2333810 (H6); 2331284 (G1@H1); 2340748 (G1@H2); 2340749 (G1@H3); 2331368 (G2@H1); 2341375 (G2@H2); 2340763 (G2@H3); 2340764 (G2@H4); 2331389 (G3@H1); 2331288 (G4@H1); 2331298 (G5@H1); 2331292 (G6@H1); 2331293 (G7@H1); 2331295 (G11@H1); 2331296 (G14@H1); 2331297 (G15@H1); 2331381 (G16@H1); 2331370 (G17@H1); 2331299 (G19@H1); 2331301 (G20@H1); 2331305 (G22@H1); 2331308 (G23@H1); 2331311 (G24@H1); 2331317 (G25@H1); 2331375 (G29@H1). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/getstructures. All relevant data are available in this paper, and its Supplementary Information and additional data were available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gale, P. A.& Steed, J. W. Supramolecular Chemistry: From Molecules to Nanomaterials (Wiley, 2012).

Chatterji, D. Basics of Molecular Recognition (CRC Press, 2016).

Houk, K. N., Leach, A. G., Kim, S. P. & Zhang, X. Binding affinities of host−guest, protein−ligand, and protein−transition-state complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 4872–4897 (2003).

Lou, X.-Y., Zhang, S., Wang, Y. & Yang, Y.-W. Smart organic materials based on macrocycle hosts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 6644–6663 (2023).

Appavoo, S. D., Huh, S., Diaz, D. B. & Yudin, A. K. Conformational control of macrocycles by remote structural modification. Chem. Rev. 119, 9724–9752 (2019).

Liu, Z., Nalluri, S. K. M. & Stoddart, J. F. Surveying macrocyclic chemistry: from flexible crown ethers to rigid cyclophanes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 2459–2478 (2017).

Chen, J. et al. Separation of benzene and toluene associated with vapochromic behaviors by hybrid[4]arene-based co-crystals. Nat. Commun. 15, 1260 (2024).

Wang, Y., Wu, S., Wei, S., Wang, Z. & Zhou, J. Selectivity separation of ortho-chlorotoluene using nonporous adaptive crystals of hybrid[3]arene. Chem. Mater. 36, 1631–1638 (2024).

Yan, M., Wang, Y., Chen, J. & Zhou, J. Potential of nonporous adaptive crystals for hydrocarbon separation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 6075–6119 (2023).

Gokel, G. W., Leevy, W. M. & Weber, M. E. Crown ethers: sensors for ions and molecular scaffolds for materials and biological models. Chem. Rev. 104, 2723–2750 (2004).

Rekharsky, M. V. & Inoue, Y. Complexation thermodynamics of cyclodextrins. Chem. Rev. 98, 1875–1918 (1998).

Wenz, G., Han, B.-H. & Müller, A. Cyclodextrin rotaxanes and polyrotaxanes. Chem. Rev. 106, 782–817 (2006).

Neri, P., Sessler, J. L. & Wang, M.-X. Calixarenes and Beyond (Springer, 2016).

Escobar, L., Sun, Q. & Ballester, P. Aryl-extended and super aryl-extended calix[4]pyrroles: design, synthesis, and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 500–513 (2023).

Mummidivarapu, V. V. S., Joseph, R., Rao, C. P. & Pathak, R. K. Suprareceptors emerging from click chemistry: comparing the triazole based scaffolds of calixarenes, cyclodextrins, cucurbiturils and pillararenes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 493, 215256 (2023).

Bleus, S. & Dehaen, W. Pillararene-inspired arenes: synthesis, properties and applications compared to the parent macrocycle. Coord. Chem. Rev 509, 215762 (2024).

Zhang, H., Liu, Z. & Zhao, Y. Pillararene-based self-assembled amphiphiles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 5491–5528 (2018).

Jie, K., Zhou, Y., Li, E. & Huang, F. Nonporous adaptive crystals of pillararenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2064–2072 (2018).

Wu, J.-R., Wu, G. & Yang, Y.-W. Pillararene-inspired macrocycles: from extended pillar[n]arenes to geminiarenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 3191–3204 (2022).

Lee, J. W., Samal, S., Selvapalam, N., Kim, H.-J. & Kim, K. Cucurbituril homologues and derivatives: new opportunities in supramolecular chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 36, 621–630 (2003).

Barrow, S. J., Kasera, S., Rowland, M. J., del Barrio, J. & Scherman, O. A. Cucurbituril-based molecular recognition. Chem. Rev. 115, 12320–12406 (2015).

Nie, H., Wei, Z., Ni, X.-L. & Liu, Y. Assembly and applications of macrocyclic-confinement-derived supramolecular organic luminescent emissions from cucurbiturils. Chem. Rev. 122, 9032–9077 (2022).

Zhuang, S.-Y., Cheng, Y., Zhang, Q., Tong, S. & Wang, M.-X. Synthesis of i-corona[6]arenes for selective anion binding: interdependent and synergistic anion–π and hydrogen-bond interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 23716–23723 (2020).

Shi, B. et al. Clamparene: synthesis, structure, and its application in spontaneous formation of 3D porous crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 146, 2901–2906 (2024).

Sawanaka, Y., Yamashina, M., Ohtsu, H. & Toyota, S. A self-complementary macrocycle by a dual interaction system. Nat. Commun. 13, 5648 (2022).

Peng, Y., Tong, S., Zhang, Y. & Wang, M.-X. Functionalized hydrocarbon belts: synthesis, structure and properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302646 (2023).

Li, B. et al. Structurally diverse macrocycle co-crystals for solid-state luminescence modulation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2535 (2024).

Bu, A. et al. Modular synthesis of improbable rotaxanes with all-benzene scaffolds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401838 (2024).

Qin, Y., Liu, X., Jia, P.-P., Xu, L. & Yang, H.-B. BODIPY-based macrocycles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5678–5703 (2020).

Martí-Centelles, V., Pandey, M. D., Burguete, M. I. & Luis, S. V. Macrocyclization reactions: the importance of conformational, configurational, and template-induced preorganization. Chem. Rev. 115, 8736–8834 (2015).

Li, S. et al. Synthesis and macrocyclization-induced emission enhancement of benzothiadiazole-based macrocycle. Nat. Commun. 13, 2850 (2022).

Escobar, L. & Ballester, P. Molecular recognition in water using macrocyclic synthetic receptors. Chem. Rev. 121, 2445–2514 (2021).

Dong, J. & Davis, A. P. Molecular recognition mediated by hydrogen bonding in aqueous media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 8035–8048 (2021).

Yu, Y. & Rebek, J. J. Reactions of folded molecules in water. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 3031–3040 (2018).

Yang, L.-P., Wang, X., Yao, H. & Jiang, W. Naphthotubes: macrocyclic hosts with a biomimetic cavity feature. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 198–208 (2020).

Zhu, Y.-J., Zhao, M.-K., Rebek, J. J. & Yu, Y. Recent advances in the applications of water-soluble resorcinarene-based deep cavitands. ChemistryOpen 11, e202200026 (2022).

Liu, Z., Dai, X., Sun, Y. & Liu, Y. Organic supramolecular aggregates based on water-soluble cyclodextrins and calixarenes. Aggregate 1, 31–44 (2020).

Roy, I., David, A. H. G., Das, P. J., Pe, D. J. & Stoddart, J. F. Fluorescent cyclophanes and their applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 5557–5605 (2022).

Neira, I., Blanco-Gómez, A., Quintela, J. M., García, M. D. & Peinador, C. Dissecting the “blue box”: self-assembly strategies for the construction of multipurpose polycationic cyclophanes. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 2336–2346 (2020).

Chun, Y. et al. Calix[n]imidazolium as a new class of positively charged homo-calix compounds. Nat. Commun. 4, 1797 (2013).

Ji, X. et al. Encoding, reading, and transforming information using multifluorescent supramolecular polymeric hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705480 (2018).

Chi, X. et al. Azobenzene-bridged expanded “texas-sized” box: a dual-responsive receptor for aryl dianion encapsulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6468–6472 (2019).

Ruiz-Botella, S., Vidossich, P., Ujaque, G. & Peris, E. A resorcinarene-based tetrabenzoimidazolylidene complex of rhodium. Dalton Trans. 49, 3181–3186 (2020).

Ji, X. et al. Physical removal of anions from aqueous media by means of a macrocycle-containing polymeric network. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2777–2780 (2018).

Li, Y.-Y., Xiao, M., Wei, D.-H. & Niu, Y.-Y. Hybrid supramolecules for azolium-linked cyclophane immobilization and conformation study: synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic degradation. ACS Omega 4, 5137–5146 (2019).

Yang, J., Hu, S.-J., Cai, L.-X., Zhou, L.-P. & Sun, Q.-F. Counteranion-mediated efficient iodine capture in a hexacationic imidazolium organic cage enabled by multiple non-covalent interactions. Nat. Commun. 14, 6082 (2023).

Koy, M., Bellotti, P., Das, M. & Glorius, F. N-Heterocyclic carbenes as tunable ligands for catalytic metal surfaces. Nat. Catal. 4, 352–363 (2021).

Izatt, R. M., Pawlak, K., Bradshaw, J. S. & Bruening, R. L. Thermodynamic and kinetic data for macrocycle interaction with cations, anions, and neutral molecules. Chem. Rev. 95, 2529–2586 (1995).

Oh, J. H. et al. Calix[4]pyrrole-based molecular capsule: dihydrogen phosphate-promoted 1:2 fluoride anion complexation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 144, 16996–17009 (2022).

Yao, Y. et al. Dynamic mechanostereochemical switching of a co-conformationally flexible [2]catenane controlled by specific ionic guests. Nat. Commun. 15, 1952 (2024).

Wang, X., Jia, F., Yang, L.-P., Zhou, H. & Jiang, W. Conformationally adaptive macrocycles with flipping aromatic sidewalls. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 4176–4188 (2020).

Wang, R., Yuan, L. & Macartney, D. H. Inhibition of C(2)-H/D exchange of a bis(imidazolium) dication upon complexation with cucubit[7]uril. Chem. Commun. 27, 2908–2910 (2006).

Li, S. et al. Inhibition of C(2)-H activity on alkylated imidazolium monocations and dications upon inclusion by cucurbit[7]uril. J. Org. Chem. 81, 9494–9498 (2016).

Yang, X. & Liu, S. Cationic cyclophanes-in-cucurbit[10]uril: host-in-host complexes showing cooperative recognition towards neutral phenol guests. Supramol. Chem. 33, 693–700 (2021).

Mooibroek, T. J., Gamez, P. & Reedijk, J. Lone pair-π interactions: a new supramolecular bond? CrystEngComm 10, 1501–1515 (2008).

Yoshimoto, F. K., Jung, I.-J., Goyal, S., Gonzalez, E. & Guengerich, F. P. Isotope-labeling studies support the electrophilic compound I iron active species, FeO3+, for the carbon−carbon bond cleavage reaction of the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme, cytochrome P450 11A1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12124–12141 (2016).

Franke, R., Selent, D. & Börner, A. Applied hydroformylation. Chem. Rev. 112, 5675–5732 (2012).

Wang, M. et al. Vapochromic behaviors of a solid-state supramolecular polymer based on exo-wall complexation of perethylated pillar[5]arene with 1,2,4,5-tetracyanobenzene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 8115–8120 (2021).

Li, E. et al. Aliphatic aldehyde detection and adsorption by nonporous adaptive pillar[4]arene[1]quinone crystals with vapochromic behavior. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 23147–23153 (2018).

Song, J.-G. et al. Crystalline mate for structure elucidation of organic molecules. Chem 10, 924–937 (2024).

Chen, S., Wojcieszak, R., Dumeignil, F., Marceau, E. & Royer, S. How catalysts and experimental conditions determine the selective hydroconversion of furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Chem. Rev. 118, 11023–11117 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Fund of China (22025107, Y.-F.H. and 22301240, S.B.), Shaanxi Fundamental Science Research Project for Chemistry & Biology (22JHZ003, Y.-F.H. and 23JHQ009, S.B.), the National Youth Top-notch Talent Support Program of China (Y.-F.H.), Xi’an Key Laboratory of Functional Supramolecular Structure and Materials, and the FM&EM International Joint Laboratory of Northwest University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-F.H. conceived the project. Y.-F.H. and S.B. analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. S.B., L.-W.Z., and Q.-W.Z. performed the most of experiments. Z.-H.W. and F.W. conducted single-crystal analyses. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jiong Zhou and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, S., Zhang, LW., Wei, ZH. et al. Calix[2]azolium[2]benzimidazolone hosts for selective binding of neutral substrates in water. Nat Commun 15, 6616 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50980-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50980-z