Abstract

We propose a method for guiding charged particles such as electrons and protons, in vacuum, by employing the exotic properties of Lagrange points. This leap is made possible by the dynamics unfolding around these equilibrium points, which stably capture such particles, akin to the way Trojan asteroids are held in Jupiter’s orbit. Unlike traditional methodologies that allow for either focusing or three-dimensional storage of charged particles, the proposed scheme can guide both non-relativistic and relativistic electrons and protons in small cross-sectional areas in an invariant fashion over long distances without any appreciable loss in energy – in a manner analogous to photon transport in optical fibers. Here, particle guiding is achieved by employing twisted electrostatic potentials that in turn induce stable Lagrange points in vacuum. In principle, guidance can be realized within the fundamental mode of the resulting waveguide, thereby presenting a prospect for manipulating these particles in the quantum domain. Our findings may be useful in a wide range of applications in both scientific and technological pursuits. These applications could encompass electron microscopies and lithographies, particle accelerators, quantum and classical communication/sensing systems, as well as methods for shuttling entangled qubits between nodes within a quantum network.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than a hundred years have passed since the discovery of electrons by Thomson in 18971. Ever since, the use of electron transport processes within various material systems has utterly revolutionized the technological landscape, ushering in an era of electronic marvels. In this regard, of paramount importance has always been to devise effective approaches in guiding electrons and, by extension, charged particles like protons and ions in vacuum. We note that methods to store charged particles in three-dimensional settings do exist, such as, for example, Paul and Penning traps2,3,4,5. These traps rely on static electric fields when used in conjunction with an oscillating electric3,4,5 or a uniform magnetic field2, in a way that overcomes the limitations imposed by Earnshaw’s theorem6. On the other hand, it is also possible to focus charged particles using quadrupole magnetic7,8,9,10,11 or electrostatic lenses9,10,12,13. Of utmost significance is the principle of strong focusing, first proposed by Christofilos14 and Courant, Livingston, and Snyder15. Indeed, in facilities like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), hundreds of quadrupole superconducting magnets are employed to periodically steer and focus protons throughout their journey. At this point, perhaps it is fair to say that the current use of such sequences of magnetic or electrostatic lenses for particle guiding is to a great extent reminiscent of pre-fiber era optical communication systems16,17 where light transport was envisaged to take place through a succession of optical lenses. Naturally, the question arises, as to whether it is possible to guide charged particles in vacuum in a manner akin to that used for light in optical fibers18.

In this work, we demonstrate that is possible to guide and confine charged particles in periodically twisted electrostatic fields by exploiting the counterintuitive attributes of Lagrange points. As in celestial mechanics, electrons and protons can be perpetually captured in such arrangements within induced Lagrange points via dynamic stabilization processes facilitated by Coriolis forces19,20. In principle, these electron/proton waveguiding structures can operate in single-mode formats with very small cross-sections where quantum mechanical effects can be manifested, in a manner that directly emulates the optical fiber paradigm18,21,22,23,24,25,26. Here, the problem is treated both quantum-mechanically and classically – up to the relativistic regime. By accounting for Larmor radiation, we find that these arrangements can exhibit small losses – thus opening up the possibility for transporting charged particles at high speeds over prolonged distances. As we will see, the approach proposed here introduces additional degrees of freedom in the sense that goes beyond the well-established strong focusing principle that relies on quadrupole fields. This same strategy can be deployed in other more common settings like for example, electron microscopies27,28,29,30 and lithographies31,32, particle accelerators33,34,35,36, and vacuum electronic and communication systems37,38 using high-speed charged particles. Finally, the prospect exists to physically shuttle qubits either between multiplexed traps or a quantum network’s nodes39,40,41,42,43,44 where in principle, adiabatic means are used to propel particles in the Lagrange waveguides.

Results

Lagrange waveguide setup

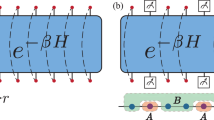

Figure 1a depicts a schematic of the proposed electron guiding system. In this arrangement, electrons are emitted from an electron gun after being accelerated by a static electric field. In principle, the electrons can be further accelerated using LINAC arrangements33,34,35,36 before injected in the guiding setup. As we will see, these high-speed electrons can be confined and guided around stable Lagrange points that are induced by a twisted electric field \(V(x,y,z)\). The twisted electric field configuration is produced by a helical metal wire (of pitch \(\Lambda\) and helical radius \(d\)) that is kept at a potential \({V}_{0}\) with respect to a surrounding metal cylinder that is grounded (See Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). In this system, the guided electrons will then be transported along a helicoidal trajectory within a small cross-section. A similar platform can be deployed to guide heavier charged particles like protons, ions, etc. Before we proceed any further, it may be useful to briefly describe the properties of Lagrange points, as they form the basis upon which the guiding system relies.

a Schematic of a possible experimental setup, to observe charged particle Trojan bound states (bright yellow beam). A stable Lagrange point is established by twisting the electrostatic potential produced by a charged helical metallic wire when kept at a potential \({V}_{0}\). b Cross-section of the setup in (a). The electron is trapped at a stable Lagrange point and follows a helical trajectory along the \(z\) axis. Stability in trapping this charged particle is provided through the Coriolis force \({{{{{\bf{F}}}}}}_{{{{{\bf{c}}}}}}\) when viewed from the co-rotating frame. \(R\) represents the distance between the center \(C\) of the grounded metallic tube and the center of the Lagrange waveguide and \(d\) is the distance between the center \(C\) and the center of the helical wire.

Lagrange points

In celestial mechanics, Lagrange points represent unique equilibrium positions where the gravitational forces from two orbiting massive bodies counteract the centrifugal force19,20. In gravitational settings (reduced three-body systems), the Lagrange points encompass five positions designated as \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{1},\,{{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{2},\,...,\) and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{5}\). The first three (\({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{1}\), \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{2}\), and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{3}\)) are colinear with respect to the two bodies and happen to be inherently unstable, while the remaining two (\({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{4}\) and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{5}\)) exhibit dynamic stability. As a result, smaller planetesimals can be indefinitely trapped around \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{4}\) and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{5}\), for example, in the case of the Trojan asteroids in the Sun-Jupiter system. Intriguingly, what dynamically stabilizes the motion of a captured third body is the Coriolis force that acts in a Sisyphean manner in spite of the fact that in the co-rotating frame, the two-dimensional transverse potential landscape exhibits a maximum at \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{4}\) and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{5}\). We note that quite recently, this Lagrange-induced waveguiding process has been demonstrated within the realm of optics26. In this respect, optical Trojan beams were guided and trapped even within defocusing refractive index profiles. Moreover, Lagrange points can be induced even from a single helicoidal potential without the need for a secondary source, as in reduced three-body systems.

Quantum wave mechanics of guided charged particles at a Lagrange point

In this section, we analyze the stationary quantum wavefunctions or modes associated with a charged particle, like an electron, when trapped and transported within a Lagrange waveguide (Fig. 1b). To explore this possibility, we use the Schrödinger equation under the assumption that the particles primarily move along the \(z\) axis with paraxial momenta \({p}_{z}=\hslash {k}_{z}\gg {p}_{x},{p}_{y}\). To investigate this problem, we employ a moving coordinate frame \({z}^{{\prime} }=z,\,{t}^{{\prime} }=t-z/{v}_{z}\) where \({v}_{z}=\hslash {k}_{z}/{m}_{e}\) represents the dominant \(z\) component of the electron’s velocity while \({m}_{e}\) denotes its corresponding mass. Moreover, \({k}_{z}\simeq 2\pi /{\lambda }_{{dB}}\) where \({\lambda }_{{dB}}\) is the electron’s de Broglie wavelength (See Supplementary Note 2). In this case, the Schrödinger equation takes the form \(i{\partial }_{z}\psi=\hat{H}^{\prime} \psi\), where \(\hat{H}^{\prime}=-{\nabla }_{x,y}^{2}/(2{k}_{z})+({m}_{e}/\hslash {k}_{z}^{2})U(x,y,z)\) and \(U(x,y,z)={eV}(x,y,z)\) indicates the twisted three-dimensional electrostatic potential in the absolute (stationary) frame (See Supplementary Note 3). At this point, it is perhaps more convenient to consider this problem within the co-rotating frame with normalized coordinates (\(u,v,\xi\)) of the helix (\({\left[u,v\right]}^{T}={{{\boldsymbol{R}}}}(\Omega Z){\left[X,Y\right]}^{T}\)) to formally decouple the twisted static electric potential \(U\) from \(Z\), in which case \(U=U\left(u,v\right)\), \((X,Y,Z)\) represent the normalized coordinates in the stationary frame and \(\Omega\) is the normalized spatial angular velocity (See Supplementary Note 4). To do so, we introduce a vector potential \({{{\bf{A}}}}={{{\mathbf{\Omega }}}}\times {{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{{{\mathbf{\Omega }}}}}\) to account for Coriolis effects where \({{{\mathbf{\Omega }}}}=2{{{\rm{\pi }}}}{z}_{0}\hat{{{{\bf{Z}}}}}/\Lambda\) with \({z}_{0}\) being the normalization factor in \(\hat{z}\) direction and \({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{{{\mathbf{\Omega }}}}}=u\hat{{{{\bf{u}}}}}+v\hat{{{{\bf{v}}}}}\) (See Supplementary Note 4). In the rotating frame, the normalized Schrödinger equation now takes the form

where \({{{{\bf{p}}}}}_{{{{\mathbf{\Omega }}}}}=-i\hat{{{{\bf{u}}}}}\partial /\partial u-i\hat{{{{\bf{v}}}}}\partial /\partial v\) is the normalized momentum operator, and \({U}_{\Omega,{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\left(u,v\right)=e{x}_{0}^{2}{m}_{e}V\left(X,Y,Z=0\right)/{\hslash }^{2}-{\Omega }^{2}{r}_{\Omega }^{2}/2\) is an effective potential that now also incorporates the centrifugal term \(-{\Omega }^{2}{r}_{\Omega }^{2}/2\) and \({x}_{0}\) is the normalization factor in \(\hat{x},\hat{y}\) directions (See Supplementary Notes 3, 4). Given that the helicoidal metallic wire is kept at a repulsive voltage \({V}_{0} \, < \, 0\) within a grounded tube of radius \(b\) (Fig. 1a), the generated electrostatic potential is expected to vary in a logarithmic fashion \(V={V}_{0}{{\mathrm{ln}}}\left(r^{\prime} /b\right)/{{\mathrm{ln}}}\left(a/b\right)\) within the stationary coordinate system (\(x,y,z\)) where \(a\) is the radius of the wire and \(r^{\prime}=\sqrt{{\left(x-d\cos \left({\Omega }_{0}z\right)\right)}^{2}+{\left(y-d\sin \left({\Omega }_{0}z\right)\right)}^{2}}\) where \({\Omega }_{0}=\Omega /{z}_{0}=2\pi /\Lambda\) represents the actual spatial angular velocity (see Supplementary Note 1). Figure 2a displays the logarithmic-like potential \(V\) when spiraling around the center of the tube \(C\) with a pitch of \(\Lambda=\) 6 \({{{\rm{cm}}}}\), a radius of \(a=275\,{{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and \(b=2\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}\) at \({V}_{0}=-2.15\,{{{\rm{kV}}}}\). Without loss of generality, here, we assume that the injected electrons have a kinetic energy of \(30\,{{{\rm{keV}}}}\). The corresponding effective potential \({U}_{\Omega,{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\left(u,v\right)\) as viewed in the co-rotating frame is depicted in Fig. 2b. For this scenario, two Lagrange points are induced (designated as \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\)) where the electrostatic repulsion balances the centrifugal force, i.e., \(\nabla {U}_{\Omega,{{{\rm{eff}}}}}=0\) (See Supplementary Note 5). In this case, it so happens that only \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) is stable while \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\), being a saddle point, is unstable. The positions of \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\) are also marked in Fig. 2a for clarity. As previously noted, \({U}_{\Omega,{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\) has a maximum at \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\). To obtain the electron quantum eigenfunctions, we solve Eq. (1) numerically. The wavefunction probability distribution corresponding to the ground state is shown in Fig. 2c. In this particular arrangement, the fundamental mode (Fig. 2c) has an elliptical Gaussian-like shape with a mean spot size radius of ~0.3 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). Similarly, Fig. 2e, g display the wavefunction profiles for the next two modes. Note that, in principle, the spot size of the ground state can be further reduced to a few nanometers by either increasing \({V}_{0}\) or by decreasing the de Broglie wavelength. To understand the nature of the trapped quantum wavefunctions, we approximately expand the effective potential around \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) to second order, i.e., \({U}_{\Omega,{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\cong -({\omega }_{1}^{2}{u}^{2}+{\omega }_{2}^{2}{v}^{2})/2\), where \({\omega }_{1}^{2},{\omega }_{2}^{2}\) represent the corresponding curvatures of this elliptical parabolic potential landscape. In this case, one can show that the ground state eigenfunction is analytically given by \({\psi }_{0}=N{e}^{-p{u}^{2}}{e}^{-q{v}^{2}}{e}^{i\eta {uv}}{e}^{i\beta Z}\) (See Methods). Interestingly, this mode involves a \({uv}\) phase distribution that is specific to this particular arrangement—a direct byproduct of Coriolis effects. This phase term is manifested in an X-like manner and happens to persist even for high-order states (Fig. 2d, f, h). Our theoretical results are confirmed by numerically solving the Schrödinger problem in both the stationary and rotating frames. As shown in Fig. 2i, the probability profile of the ground state remains invariant (trapped) during propagation while twisting around the center C—a hallmark of the guiding behavior. Finally, we note that Lagrange waveguiding is also possible even in the case where \({V}_{0}\) is attractive (\({V}_{0} \, > \,0\)) (See Supplementary Note 5).

a An induced logarithmic, defocusing, and spiraling electrostatic potential when viewed within the stationary frame at \({{{z}}}=0\). This potential profile rotates along z at a constant spatial angular velocity \({\Omega }_{0}\) around the center C \((0,0)\). The corresponding iso-contour potential lines are also shown. b In the co-rotating frame (\({{{u}}},{{{v}}}\)), the effective potential \({{{{\rm{U}}}}}_{\Omega,{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\) now incorporates centrifugal effects and exhibits two Lagrange points, \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\). \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\) is a saddle point and hence is unstable. On the other hand, \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) (\({{{{u}}}}_{{{{l}}}},{{{{v}}}}_{{{{l}}}}\)) exhibits a maximum, around which dynamics are stabilized through Coriolis effects. For comparison, the positions of \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\) are also marked in (a). c, e, g Numerically obtained quantum wavefunction probability distributions for the fundamental (c) and next two electron Trojan modes (e, g). The quantum states in (c, e, g) at \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) correspond to the potential landscapes in (a, b). In this case, the quantum modes are elliptical in the (\({{{{u}}}}^{{\prime} },{{{{v}}}}^{{\prime} }\)) system where \({{{{u}}}}^{{\prime} }={{{u}}}-{{{{u}}}}_{{{{l}}}}\,,\,{{{{v}}}}^{{\prime} }={{{v}}}-{{{{v}}}}_{{{{l}}}}\). d, f, h Respective phase structures associated with these three electron wavefunction states. In all cases, the phase profile exhibits an X-shaped pattern. i Stable propagation of the quantum Trojan ground state shown in (c), as obtained numerically by solving Eq. (1). The quantum probability function remains invariant along its helical path. The helix pitch in (a–i) is taken to be \(\Lambda=6\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}\) while the electron energy is assumed to be 30 \({{{\rm{keV}}}}\). The normalization factor \({{{{x}}}}_{0}\) in (b–h) is taken to be 1 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\).

Dynamics of non-relativistic and relativistic charged particles in a Lagrange waveguide

In this section, we investigate this same charged particle guiding system under both relativistic and non-relativistic conditions. This classical treatment is imperative given that one has to understand how a Lagrange waveguide will respond under incoherent excitation of several modes. As before, we consider the periodic spiraling electric potential distribution \(U\left(x,y,z\right)=U\left(x,y,z+\Lambda \right)\) within the co-rotating frame \(({u}_{{\Omega }_{0}},{v}_{{\Omega }_{0}},{\xi }_{{\Omega }_{0}})\) with actual units where \({\xi }_{{\Omega }_{0}}=z\), \({[{u}_{{\Omega }_{0}},{v}_{{\Omega }_{0}}]}^{T}={{{\boldsymbol{R}}}}({\Omega }_{0}z){\left[x,y\right]}^{T}\). In this case, the Newtonian dynamics \({u}_{{\Omega }_{0}}(z),{v}_{{\Omega }_{0}}(z)\), when viewed in the transverse plane, are described by (See Supplementary Note 6)

where again \({U}_{{\Omega }_{0},{{{\rm{eff}}}}}({u}_{{\Omega }_{0}},{v}_{{\Omega }_{0}})=\, {-}{m}_{e}{\Omega }_{0}^{2}({u}_{{\Omega }_{0}}^{2}+{v}_{{\Omega }_{0}}^{2})/2+{U}_{{\Omega }_{0}}({u}_{{\Omega }_{0}},{v}_{{\Omega }_{0}})\) where the subscript ‘\({\Omega }_{0}\)’ represents the physical parameters with actual units, and the second term in the RHS of Eq. (2) accounts for Coriolis effects. To further exemplify this situation, let us consider electron confinement around a stable Lagrange point. To do so, we analyze the same waveguide configuration considered in the previous section. In this case, 30-\({{{\rm{keV}}}}\) electrons are injected in a 30 \({{{\rm{cm}}}}\) long Lagrange waveguide after passing through an aperture of radius \({r}_{0}=10\,{{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). The thermionically emitted electrons from a heated cathode (of temperature \(T=1000\,{{{\rm{K}}}}\)) obey a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution with a probability density \(f({v}_{i})\propto \exp (-{v}_{i}^{2}/2{\sigma }_{v}^{2})\), where \(i=x,y\), \({\sigma }_{v}=\sqrt{{k}_{B}T/{m}_{e}}\) denotes the velocity variance and \({k}_{B}\) represents the Boltzmann constant. Figure 3a depicts the stable trajectory of an electron when trapped around the \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) Lagrange point over a distance of 30 \({{{\rm{cm}}}}\). The waveguiding action of this arrangement is obvious. Meanwhile, Fig. 3b displays both the spatial and velocity distribution of the injected electrons when the aperture is centered at \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\). In the absence of a repelling potential (\({V}_{0}=0\)), the electron beam spreads or diffracts to a spot size of \(\sim 1\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\) after 30 c\({{{\rm{m}}}}\) of propagation (Fig. 3c). On the other hand, for \({V}_{0}=-2.15\,{{{\rm{kV}}}}\), a Lagrange waveguide is induced that now stably guides the electron beam with a spot size of \(\sim 65\,{{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) (Fig. 3d). Note that here, the beam spot size is considerably larger than the mean spot size of the fundamental mode (0.3 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\)) since several modes are incoherently excited under these conditions. In the setup proposed here, space-charge effects can be safely ignored for electron currents below \({{{\rm{mAs}}}}\) (Supplementary Note 7, ref. 10).

a Stable trapping of an electron unfolding around \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) for the potential landscapes depicted in Fig. 2a, b, as viewed within the co-rotating frame. The normalization factor \({{{{x}}}}_{0}\) here is taken to be 1 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). b Spatial and velocity distributions associated with the injected electrons when the aperture at the input of the Lagrange waveguide has a radius of 10 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and is centered at \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\). c Histogram of electron spatial distribution after 30 cm in free space (\({{{{V}}}}_{0}=0\)). In this case, the electron beam diffracts to a spot size of ~1 mm. d Histogram of electron spatial distribution after 30 cm of propagation in a Lagrange waveguide when the repelling potential is \({{{{V}}}}_{0}=-2.15\,{{{\rm{kV}}}}\). In this latter scenario, the electron beam is stably guided with a mean spot size of ~65 μm. e Transverse trajectory (blue curve) of a high-speed electron (\({{{{v}}}}_{{{{e}}}}\) = 0.999 c) over 100 m. The yellow dashed line depicts the Lagrange point position, located at a radius of ~112 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) from the center. The electron was positioned at a distance ~4 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) away from the Lagrange point. f Electron beam transverse distribution histogram (for \({{{{v}}}}_{{{{e}}}}\) = 0.999 c) after 100 m of propagation in a Lagrange waveguide when the repelling potential is \({{{{V}}}}_{0}\) = \(-80\,{{{\rm{kV}}}}\). The electron beam is stably guided with a mean spot size of ~215 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). The scaling bar (yellow) in (c, d, f) corresponds to 300 μm while that (green) in the inset of (d, f) to 200 \({{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\).

This same problem is now analyzed in the relativistic regime by solving the equation of motion45 \(m(d{{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{e}}}}}/{dt})={{{\bf{F}}}}-({{{\bf{F}}}}{{{\cdot }}}{{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{e}}}}})({{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{e}}}}}{{{/}}}{c}^{2})\) where \({{{\bf{F}}}}=-e\nabla V\) (Supplementary Note 8). In this case, one can show that, again, the Lagrange point is located on the same line that connects the center with the helicoidal wire source at a distance \(l\) from the center. For a stable Lagrange point \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\), this distance is given by \(l=[d-\sqrt{{d}^{2}+4e\Theta /({m}_{0}\gamma {\Omega }_{0}^{2}{v}_{z}^{2})}]/2\) where \(\gamma=1/\sqrt{1-{v}_{e}^{2}/{c}^{2}}\) is the Lorentz factor, \({m}_{0}\) is the rest mass, \(\Theta={{{{\rm{V}}}}}_{0}/{{\mathrm{ln}}}(a/b)\) and \({v}_{e}^{2}={\sum}_{i=x,y,z}{v}_{i}^{2}= {v}_{z}^{2}(1+{\Omega }_{0}^{2}{l}^{2})\). To confirm trapping and guidance at the relativistic Lagrange point \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\), numerical simulations are carried out when \({v}_{e}=0.999{c}\). The trajectory of a high-speed electron (\({v}_{e}=0.999{c}\)) around \({{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) is depicted in Fig. 3e after 100 m of propagation. On the other hand, a histogram of an electron beam is also shown in Fig. 3f for this same distance. For these figures, the system parameters were taken to be \(\Lambda=6\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}\), \(a=500\,{{{\upmu }}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), \(d=1.8\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\), \(b=2\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}\), and \({V}_{0}=-80\,{{{\rm{kV}}}}\). Under these conditions, the relativistic Lagrange point is located at a distance of \(\sim 112\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) from the center. In obtaining the results of Fig. 3e,f, we again assume that the thermionic electrons emitted from a heated cathode (of temperature \(T=1000\,{{{\rm{K}}}}\)) after acceleration, entered the relativistic Lagrange waveguide through an aperture of radius \(10\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). The pertinent velocity and spatial distributions are depicted in Fig. 3b.

Transporting protons and heavier charged particles in Lagrange waveguides

This same approach can also be used to guide heavier charged particles like protons and ions. Table 1 provides possible design parameters for transporting protons, Strontium (88Sr+), and Ytterbium ions (171Yb+) after acquiring a terminal velocity \({v}_{z}\) of \({ \sim 10}^{8}\,{{{\rm{m}}}}/{{{\rm{s}}}}\). The spot size of the quantum ground state (fundamental mode) in the Lagrange waveguide is also given for comparison purposes. The methodology used to evaluate these parameters is provided in Supplementary Note 5.

Radiation losses

In this section, we provide an estimate for the energy loss rate associated with a charged particle when trapped in a Lagrange waveguide. Given that the particle will be transported along a helical trajectory, it will inevitably radiate energy because of transverse acceleration. In general, in this twisted arrangement, the respective dynamics can be decomposed into a uniform motion \({v}_{z}\) and a transverse velocity \({v}_{\perp }\) (\({v}_{\perp }\ll {v}_{z}\)) that leads to a centripetal acceleration \({{{{\bf{a}}}}}_{{{{\bf{e}}}}}=-\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}}{v}_{\perp }^{2}/R\) which is perpendicular to the particle’s total velocity \({{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{e}}}}}={v}_{z}\hat{{{{\bf{z}}}}}{{{+}}}{{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{{{{\perp }}}}\). In the latter expression, \(R\) represents the radius of the helicoidal Lagrange waveguide. In this case, the relativistic radiation loss rate can be obtained from46 (See Supplementary Note 9)

here \(\gamma=1/\,\sqrt{1-{\beta }_{e}^{2}}\) and \({{{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}}_{{{{\bf{e}}}}}={{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{e}}}}}/c\) is the velocity ratio. In this regard, the radiation loss rate experienced by a 30-keV electron in a Lagrange waveguide (Fig. 1a) with \(\Lambda=6\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}\) and \(R=0.74\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\) will be 0.27 \({{{\rm{eV}}}}/{{{\rm{s}}}}\), which is indeed negligible, given that it translates to \(\sim 4\times {10}^{-10}{{{\rm{dB}}}}/{{{\rm{km}}}}\). On the other hand, a 1-TeV proton, moving at a speed \({v}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}=(1-4.4\times {10}^{-7})c\) in a Lagrange waveguide with \(\Lambda=60\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}\) and \(R=260\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\) (with wire rotation radius \(d=\)1.8 mm, \({V}_{0}=\) 220 kV) is expected to encounter a radiation loss rate of \(302\) \({{{\rm{eV}}}}/{{{\rm{s}}}}\), which is again minute as compared to the energy of the particle. Another source for losses can be manifested when a charged particle is moving close to an imperfectly conducing surface47, in which case the drag force leads to Ohmic heating. For the 30 keV electron example considered above, if a copper outer tube has a radius of \(b=2\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}\), the drag loss rate is predicted to be only 66.3 \({{{\rm{n}}}}{{{\rm{eV}}}}/{{{\rm{s}}}}\). In addition, the thermal noise generated by the twisted wire is also considered and expected to be of no practical significance in this Lagrange waveguide arrangement (Supplementary Note 10). Finally, it should be noted that, unlike photons for which loss is equivalent to complete annihilation, in these waveguides, loss merely means a reduction in the energy of the particles. Consequently, charged particles can still preserve properties like entanglement under appropriate conditions.

The above estimates indicate that Lagrange waveguides may indeed be promising in guiding charged particles in accelerator designs or in extremely low-loss electron communication systems that operate in either the classical or quantum domain37,38.

Discussion

Here, we have demonstrated a methodology for trapping charged particles such as electrons, protons or ions by utilizing the features of Lagrange points. This approach enables charged particle guiding (up to relativistic speeds) in a manner akin to that responsible for light transport in optical fibers. At the induced Lagrange points, the electron/ion beams can be stably captured, because of Coriolis effects, in well-defined quantum states produced by long-range spiraling electrostatic forces. Unlike other charge particle transport approaches relying on quadrupole potential distributions8,9, our methodology provides additional degrees of freedom in inducing multiple parallel guiding channels that can be used to enable quantum coupling/splitting arrangements. The work presented here may potentially be employed for transporting accelerated charged particles in a vacuum where guiding has thus far remained out of reach. Of interest would be to investigate the prospect of manipulating these beams in single-mode regimes where quantum phenomena can be directly manifested. Along these lines, the possibility of shuttling entangled ion qubits over long distances among quantum charge-coupled device systems (where magnetic decoherence could be an issue39,48) using electrostatic Lagrange waveguides, can be another important direction.

Methods

Analytical solution for the fundamental Trojan mode in a twisted parabolic potential

Here we provide an analytical solution for the fundamental quantum Trojan eigenstate in a twisted parabolic elliptical potential. The stable Lagrange point is located at (\({u}_{l},{v}_{l}\)) within the (\(u,v\)) system. To do so, we first obtain this solution when the normalized potential is shifted to the center \(C\) (See Supplementary Note 4), in which case, to first order \({U}_{\Omega,{{{\rm{eff}}}}}={U}_{\max }\,-\left({\omega }_{1}^{2}{u}^{2}+{\omega }_{2}^{2}{v}^{2}\right)/2\). In this case, the quantum wavefunction envelope obeys

It can be shown that the ground state of Eq. (4) is given by an elliptical Gaussian wavefunction:

where \(p,q \, > \,0\) (\(p,q \in {{{{\mathcal{R}}}}}^{+}\)) and \(N\) is a normalization factor. To determine the constants involved in Eq. (5), we substitute Eq. (5) in (4) from where we find

By comparing terms associated with \({u}^{2}\), \({v}^{2}\) and \({uv}\), the following equations are obtained

and

From Eq. (9), we find \(\eta=\Omega (q-p)/\left(p+q\right) \, < \,|\Omega {{|}}\). Meanwhile Eqs. (7) and (8) lead to

Given that \(\eta \, < \,\left|\Omega \right|\), one has to select the negative sign in Eqs. (11–1) and the positive sign in Eq. (11–2). Therefore,

From Eq. (12), we obtain the following two relations

By squaring Eqs. (13), one finds

from where we obtain

Hence, from Eq. (9), we directly establish the relation

Finally, from Eq. (12), \(p,{q}\) can now be determined:

For these \(p,{q}\) solutions to be real and positive, one requires that26 \(2\Omega \, > \,{\omega }_{1}+{\omega }_{2}\). This ground state solution now can be translated to the actual position of the stable Lagrange point (\({u}_{l},{v}_{l}\)) where the effective potential \({U}_{\Omega,{{{\rm{eff}}}}}={U}_{\max }-({\omega }_{1}^{2}{(u-{u}_{l})}^{2}+{\omega }_{2}^{2}{(v-{v}_{l})}^{2})/2\). In this case, the corresponding eigenmode is given by ref. 23 \({\psi }_{{u}_{i},{v}_{i}}=\psi \left(u-{u}_{l},v-{v}_{l}\right){e}^{i\Phi (u,v)}\), where \(\Phi \left(u,v\right)=\Omega \left({u}_{l}v-{v}_{l}u\right)\).

The dynamics of the Trojan mode can be solved numerically under any arbitrary initial conditions using beam propagation methods that rely on fast Fourier transforms (BPM-FFT). The quantum Trojan eigenstates supported by the actual effective potential around a stable Lagrange point (like the one depicted in Fig. 2b) are obtained by numerically solving Eqs. (1) or (4). In this case, the eigenvalue problem is solved using finite-difference methods (FDM).

Data availability

All other data supporting the plots and findings within this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon request, subject to restrictions due to ongoing patent considerations. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The numerical codes used in this study (MATLAB and COMSOL) are available upon request from the corresponding authors, subject to restrictions due to ongoing patent considerations.

Change history

11 September 2024

In the PDF of this article, some mathematical expressions did not display correctly. On page 3 and 4, the bolded variable Ω should not have been in italics. The original article PDF has now been corrected. The HTML was unaffected.

11 September 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52420-4

References

Thomson, J. J. X. L. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin of Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science (Taylor & France, 1897).

Brown, L. S. & Gabrielse, G. Geonium theory: physics of a single electron or ion in a Penning trap. Rev. Mod. Phys. 58, 233–311 (1986).

Paul, W. Electromagnetic traps for charged and neutral particles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 531–540 (1990).

Drewsen, M., Brodersen, C., Hornekær, L., Hangst, J. S. & Schifffer, J. P. Large ion crystals in a linear Paul trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2878–2881 (1998).

Matthiesen, C., Yu, Q., Guo, J., Alonso, A. M. & Häffner, H. Trapping electrons in a room-temperature microwave Paul trap. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011019 (2021).

Earnshaw, S. On the nature of the molecular forces which regulate the constitution of the luminiferous ether. Trans. Camb. Philos. Soc. 7, 97 (1848).

Dayton, I. E., Shoemaker, F. C. & Mozley, R. F. The measurement of two dimensional fields. Part II: study of a quadrupole magnet. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 25, 485–489 (1954).

Enge, H. A. Ion focusing properties of a quadrupole lens pair. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 30, 248–251 (1959).

Pierce, J. R. Theory and Design of Electron Beams (Books on Demand, 1954).

Tsimring, S. E. Electron Beams and Microwave Vacuum Electronics. (John Wiley & Sons, 2006).

Mendel, J. T., Quate, C. F. & Yocom, W. H. Electron beam focusing with periodic permanent magnet fields. Proc. IRE 42, 800–810 (1954).

Tien, P. K. Focusing of a long cylindrical electron stream by means of periodic electrostatic fields. J. Appl. Phys. 25, 1281–1288 (1954).

Clogston, A. M. & Heffner, H. Focusing of an electron beam by periodic fields. J. Appl. Phys. 25, 436–447 (1954).

Christofilos, N. Focussing system for ions and electrons. US patent 2,736,799 (1956).

Courant, E. D., Livingston, M. S. & Snyder, H. S. The strong-focusing synchroton–a new high energy accelerator. Phys. Rev. 88, 1190–1196 (1952).

Marcuse, D. Propagation of light rays through a lens-waveguide with curved axis. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 43, 741–753 (1964).

Miller, S. E. Communication by laser. Sci. Am. 214, 19–27 (1966).

Snyder, A. W. & Love, J. D. Optical Waveguide Theory (Chapman and Hall, 1983).

Bannikova, E. & Capaccioli, M. Foundations of Celestial Mechanics (Springer Cham, 2022).

Pérez-Villegas, A., Portail, M., Wegg, C. & Gerhard, O. Revisiting the tale of Hercules: how stars orbiting the Lagrange points visit the sun. Astrophys. J. Lett. 840, L2 (2017).

Knight, J. C. Photonic crystal fibres. Nature 424, 847–851 (2003).

Birks, T. A., Knight, J. C. & Russell, P. S. J. Endlessly single-mode photonic crystal fiber. Opt. Lett. 22, 961–963 (1997).

Ibanescu, M., Fink, Y., Fan, S., Thomas, E. L. & Joannopoulos, J. D. An all-dielectric coaxial waveguide. Science 289, 415–419 (2000).

Plotnik, Y. et al. Observation of unconventional edge states in ‘photonic graphene’. Nat. Mater. 13, 57–62 (2014).

Hsu, C. W., Zhen, B., Stone, A. D., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Bound states in the continuum. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16048 (2016).

Luo, H. et al. Guiding Trojan light beams via Lagrange points. Nat. Phys. 20, 95–100 (2024).

Muller, D. Structure and bonding at the atomic scale by scanning transmission electron microscopy. Nat. Mater. 8, 263–270 (2009).

de Boer, P., Hoogenboom, J. P. & Giepmans, B. N. G. Correlated light and electron microscopy: ultrastructure lights up! Nat. Methods 12, 503–513 (2015).

Haider, M. et al. Electron microscopy image enhanced. Nature 392, 768–769 (1998).

Zewail, A. H. Four-dimensional electron microscopy. Science 328, 187–193 (2010).

Vieu, C. et al. Electron beam lithography: resolution limits and applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 164, 111–117 (2000).

Tu et al. R. Direct X-ray and electron-beam lithography of halogenated zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Nat. Mater. 20, 93–99 (2021).

Peralta, E. A. et al. Demonstration of electron acceleration in a laser-driven dielectric microstructure. Nature 503, 91–94 (2013).

Chlouba, T. et al. Coherent nanophotonic electron accelerator. Nature 622, 476–480 (2023).

Leedle, K. J., Fabian Pease, R., Byer, R. L. & Harris, J. S. Laser acceleration and deflection of 96.3 keV electrons with a silicon dielectric structure. Optica 2, 158–161 (2015).

Black, D. S. et al. Net acceleration and direct measurement of attosecond electron pulses in a silicon dielectric laser accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 264802 (2019).

Cozzolino, D., Da Lio, B., Bacco, D. & Oxenløwe, L. K. High-dimensional quantum communication: benefits, progress, and future challenges. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2, 1900038 (2019).

Paraïso, T. K. et al. A photonic integrated quantum secure communication system. Nat. Photonics 15, 850–856 (2021).

Kielpinski, D., Monroe, C. & Wineland, D. J. Architecture for a large-scale ion-trap quantum computer. Nature 417, 709–711 (2002).

Bruzewicz, C. D., Chiaverini, J., McConnell, R. & Sage, J. M. Trapped-ion quantum computing: progress and challenges. Appl. Phys. Rev. 6, 021314 (2019).

Walther, A. et al. Controlling fast transport of cold trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 080501 (2012).

Monroe, C. & Kim, J. Scaling the ion trap quantum processor. Science 339, 1164–1169 (2013).

Brown, K. R., Kim, J. & Monroe, C. Co-designing a scalable quantum computer with trapped atomic ions. npj Quantum Inf. 2, 16034 (2016).

Krutyanskiy, V. et al. Entanglement of trapped-ion qubits separated by 230 meters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 050803 (2023).

Møller, C. The Theory of Relativity (Clarendon Press, 1952).

Zangwill, A. Modern Electrodynamics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Boyer, T. H. Penetration of the electric and magnetic velocity fields of a nonrelativistic point charge into a conducting plane. Phys. Rev. A 9, 68–82 (1974).

Wang, P. et al. Single ion qubit with estimated coherence time exceeding one hour. Nat. Commun. 12, 233 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (MURI) award on Novel light-matter interactions in topologically non-trivial Weyl semimetal structures and systems (award no. FA9550-20-1-0322)(M.K., D.N.C., H.L., Y.W., and G.G.P.), AFOSR MURI award on Programmable systems with non-Hermitian quantum dynamics(award no. FA9550-21-1-0202) (M.K., D.N.C., H.L., Y.W., and G.G.P.), ONR MURI award on the classical entanglement of light (award no. N00014-20-1-2789) (M.K., D.N.C., H.L., Y.W., and G.G.P.), the Army Research Office (W911NF-23-1-0312) (M.K., D.N.C., and G.G.P.), the Department of Energy (DE-SC0022282) (D.N.C. and H.L.), W.M. Keck Foundation (D.N.C.), MPS Simons collaboration (Simons grant no. 733682) (D.N.C.), US Air Force Research Laboratory (FA86511820019) (D.N.C.), Israel Ministry of Defense (IMOD: 4441279927) (D.N.C.) and AFRL – Applied Research Solutions (S03015) (FA8650-19-C-1692) (M.K.). All authors acknowledge the Global Research Code on the development, implementation, and communication of this research. For the purpose of transparency, we have included this statement on inclusion and ethics. This work cites a comprehensive list of research from around the world on related topics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. and D.N.C. conceived the idea. H.L., Y.W., G.G.P., M.K. and D.N.C. developed the theory. All the authors contributed to the writing of the original draft, review, and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: An invention disclosure related to the subject matter of this manuscript has been filed, and a patent application is currently underway. The details of the patent information are provided: [1] US Provisional, Serial No. 63/528,037, Applicant: Univ. of Southern California, Inventors: Mercedeh Khajavikhan, Haokun Luo, Demetrios N. Christodoulides, and Yunxuan Wei, was filed on July 20, 2023. Location and Institution: US, the US provisional. This application is now expired. [2] PCT Application, Serial No. PCT/US2024/38833, Applicant: Univ. of Southern California, Inventors: Mercedeh Khajavikhan, Haokun Luo, Demetrios N. Christodoulides, and Yunxuan Wei, was filed on July 19, 2024. Location and Institution: WIPO, the PCT. This application claims priority to the previous US provisional application and is pending.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks François Fillion-Gourdeau and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, H., Wei, Y., Pyrialakos, G.G. et al. Guiding charged particles in vacuum via Lagrange points. Nat Commun 15, 6882 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51083-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51083-5