Abstract

Materials demonstrating positive thermal expansion (PTE) or negative thermal expansion (NTE) are quite common, whereas those exhibiting zero thermal expansion (ZTE) are notably scarce. In this work, we identify the mechanical descriptors, namely in-plane tensile stiffness and out-of-plane bending stiffness, that can effectively classify PTE and NTE 2D crystals. By utilizing high throughput calculations and the state-of-the-art symbolic regression method, these descriptors aid in the discovery of ZTE or 2D Invar monolayers with the linear thermal expansion coefficient (LTEC) within ±2 × 10−6 K−1 in the middle range of temperatures. Additionally, the descriptors assist the discovery of large PTE and NTE 2D monolayers with the LTEC larger than ±15 × 10−6 K−1, which are so-called 2D anti-Invar monolayers. Advancing our understanding of materials with exceptionally low or high thermal expansion is of substantial scientific and technological interest, particularly in the development of next-generation electronics at the nanometer or even Ångstrom scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dimensions of the solids undergo reversible expansion or dilatation at a macroscopic level when they are heated or cooled due to alterations in the thermal vibrations inherent within their crystal structure, which can be measured by the linear coefficient of thermal expansion (α, LCTE)1,2. Most materials exhibit positive thermal expansion (PTE) coefficients, which leads to expanded lattices with increasing temperature due to the population of high-energy anharmonic phonons3. While uncommon, some materials expand when cooled, demonstrating negative thermal expansion (NTE). Even more exceptional is zero thermal expansion (ZTE, α ≈ 0), also called the Invar effect, where the material neither expands nor contracts volumetrically within specific temperature ranges2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Since the first discovery of the Invar in 1897 by Guillaume9 and then won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1920, some Invar materials have been found, including ferromagnetic alloys, ferroelectric relaxors, silica-based glasses and crystals with nano-porous structure2,6,7,8,10,11,12. The Invar materials are widely used in temperature-sensitive devices and high antithermal shock applications, such as the construction of calibrated, high-precision mechanical and optical instruments, such as seismographs, telescope technology on Earth and in space, spring watches with atomic time standards, heat-engine components and so on2,5. Materials with very low thermal expansion are not only crucial for practical applications but also fascinating scientifically.

In recent decades, substantial advancements in the field of nanofabrication have contributed to the reduction in the size of electronic devices to unprecedented dimensions, reaching scales as small as nanometers and even extending to Ångstrom levels13,14,15,16. The 2D material monolayers can be used as ideal building blocks to create devices and instruments with the size of nanometers or even Ångstrom. The thermal expansion properties of 2D materials show significant importance in electronic and optical applications since the accumulated thermal stress/strain would degrade the performance and stability under varying temperatures17. The reported α for 2D crystal either shows PTE (like MoS2) or NTE (like graphene)18,19. However, by now, no 2D crystal monolayer with ZTE or 2D Invar has been discovered. Recently developed 2D materials databases, such as C2DB, 2DMatPedia, and JARVIS, contain more than 10000 2D materials20,21,22. It makes us use data mining and machine learning methods to discover and understand the materials with remarkable properties, rather than study materials case by case23,24,25,26. Considering the existence of both PTE and NTE 2D crystals, we believe the presence of ZTE counterparts among these materials.

Recently, employing active learning, two high-entropy alloys (bulk Invar) featuring remarkably low α of ~2 × 10−6 K−1 were identified10. In this work, the art-of-state machine learning methods of classification and symbolic regression are used to advance the understanding and discovery of 2D Invar monolayers. A general magnetism for Invar materials is that a negative thermal expansion coefficient counteracts a PTE of the lattice. Herein, we identify the mechanical descriptors for thermal expansion from extensive data, that is in-plane tensile stiffness and out-of-plane bending stiffness. These two descriptors demonstrate effectiveness in the classification of PTE and NTE 2D crystals. By utilizing high throughput calculations and the state-of-the-art symbolic regression method, these descriptors aid in the discovery of 2D crystals with exceptionally zero, positive, and negative thermal expansion. We predict the existence of ZTE 2D crystals or 2D Invar materials with remarkably low LTEC in the middle range of temperatures, following the criteria ∣α∣ < 2 × 10−6 K−1 proposed in the review paper of R. Roy and co-workers2. We also discovered 2D crystals with extremely large thermal expansion (ELTE), that is extreme PTE (EPTE) and NTE (ENTE), which is called the anti-Invar effect27, with α larger than ±15 × 10−6 K−1. Enhancing our comprehension of materials exhibiting exceptionally low or high thermal expansion holds significant scientific and technological promise, notably in broadening the scope of applications for 2D materials in the post-Moore era13.

Results

In-plane and out-of-plane deformation modes of 2D crystals

At a finite temperature, a free-standing two-dimensional material sheet exhibits both in-plane and out-of-plane deformation modes28. For simplification, we employ a one-dimensional (1D) chain model to illustrate this question, as depicted in Fig. 1a. The in-plane mode is determined by the intrinsic expansion of chemical bonds that the length is enlarged with the rising of temperature29, thus resulting in a positive contribution to the thermal expansion. Conversely, the out-of-plane mode due to the thermal fluctuations contributes to the in-plane contraction, which has been identified as the origin of NTE behavior30. Figure 1b illustrates the atomic configurations of graphene, showcasing the ripples induced by thermal fluctuations. Under the competition between the in-plane and out-of-plane modes, 2D crystal monolayers exhibit diverse thermal expansion behaviors. For example, the graphene exhibits NTE behavior that α = −3.33 × 10−6 K−1 at 300 K and α < 0 up to 2500 K (as shown in Fig. 1c)19. While MoS2 is PTE from about 20–1000 K that α increases with temperature and α = 7.26 × 10−6 K−1 at 600 K.

a One-dimensional atomic chain model for the in-plane and out-of-plane deformation. b The atomic configurations of the ripple of graphene membrane. c The linear thermal expansion coefficient (α) of graphene and MoS2(2H) at temperatures ranging from 0 K to 1000 K. The inset shows the crystal structures of graphene and MoS2.

Data-driven classification of PTE and NTE 2D crystals

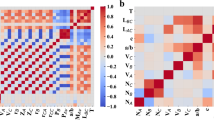

To achieve rational classifications of PTE and NTE 2D crystals, we take into account pre-existing physical knowledge to select physically meaningful features, including thickness (h), volume per atom (vpa), average bond length (abl), average atomic radius (aar), bond density (bd), in-plane stiffness E2D and out-of-plane bending stiffness D. By using random forest method31, we find the most important features for thermal expansion coefficient of 2D crystal monolayers are E2D and D as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The result is reasonable that these two mechanical properties describe the ability of 2D crystals to resist in-plane and out-of-plane deformation as mentioned above, respectively. To confirm the rationality of E2D and D to the thermal expansion of 2D crystals, we employ the recently developed sure independence screening sparsifying operator (SISSO) method, which is a compressed sensing-based methodology that can generate predictive models and classification descriptors32. We trained a SISSO classification model to separate PTE and NTE 2D crystals using E2D and D (Fig. 2a). Two descriptors (S) are obtained, that is S1 = 1/D and \({S}_{2}=1/{E}_{2{{{\rm{D}}}}}^{2}\). Herein, the separation line is obtained by a linear support vector machine (SVM) and all of the data are perfectly classified by the classification model. We find that the materials with similar S1 (or S2), the farther away from the classification line, the larger of the value of α is. For example, the E2D of WSe2 (115.81 N/m) is similar to SnO2 (119.34 N/m), but the D of WSe2 (11.05 eV) is 2.73 times of SnO2 (4.05 eV). Thus WSe2 is farther from the separation line than SnO2 (see Fig. 2a), and we find the α of WSe2 (8.43 × 10−6 K−1 at 500 K) is larger than SnO2 (4.07 × 10−6 K−1 at 500 K). Figure 2b shows the temperature dependence of the LTECs for 2H phase MoS2, MoSe2, and MoTe2 and their positive LTECs follow the order of MoS2 < MoSe2 < MoTe2. It can be understood that the E2D follows the order of MoS2 (123.12 N/m) > MoSe2 (103.26 N/m) > MoTe2 (78.50 N/m), while the bending stiffness D follows the order of MoS2 (8.27 eV) < MoSe2 (9.59 eV) < MoTe2 (10.37 eV) (see inset in Fig. 2b). Therefore, the classification model can assist us in understanding thermal expansion of 2D crystals and discovering that with either significantly large or zero thermal expansion. The EPTE 2D crystals should be distributed far below the separation line, demonstrating low E2D and high D. Similarly, the ENTE 2D crystals should be situated significantly above the separation line, exhibiting high E2D and low D. The ZTE materials are expected to be distributed near the separation line as the balance of in-plane and out-of-plane deformation.

a The positive thermal expansion (PTE)/negative thermal expansion (NTE) classification map for 2D crystals (in logarithmic coordinate) using in-plane stiffness E2D and bending stiffness D. All of the training data are well classified into two groups (blue dots represent NTE materials and red dots represent PTE materials at the temperature range of 300–1000 K). The separation line is obtained by linear support vector machine (SVM) with descriptors found by sure independence screening sparsifying operator (SISSO). b The LTECs (α) of MoS2, MoSe2, MoTe2 (here are all 2H phases) as a function of temperature. The inset shows their D. All the data of E2D and D can be found in Supplementary File. Unless specified otherwise, all transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) discussed in this work are the 2H phase.

The interpretation of mechanical descriptors

The descriptors obtained by the SISSO method offer distinct physical insights and are explainable. The descriptor S1 represents the in-plane constriction caused by out-of-plane thermal fluctuations (as shown in Fig. 1a). Considering a square sheet with the of size L0 × L0, the in-plane contraction can be quantified by the bending energy based on the statistical mechanics of membranes (see detailed derivation in SI)33. The bending energy of bend configuration can be expressed in terms of the Fourier coefficients as34,35, \({U}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}=\frac{{L}_{0}^{2}}{2}\sum D| {{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}{| }^{4}| \bar{w}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}){| }^{2}\), where q is wave-number vector in 2D space, \(\bar{w}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\) is the Fourier coefficients. The probability density function of each possible bending configuration can be given by Boltzmann distribution as \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\propto \exp (-{U}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}/{k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T)\)36, and the expectation of out-plane contraction strain is \(\left\langle {\varepsilon }_{x}\right\rangle={\mu }_{n}{k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T/16{\pi }^{2}D\), where μn is a dimensionless parameter, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature. Therefore, \(\alpha \sim \left\langle \varepsilon \right\rangle \sim 1/D\). The descriptor S2 represents in-plane thermal expansion as a result of anharmonic effect33. Assuming the out-of-plane modes are completely suppressed (that is pure 2D deformation), the in-plane thermal expansion coefficient (α2D) of a solid depends on the intrinsic thermal expansion coefficient of internal bonds αb37,38. According to the empirical relationship proposed by H. Megaw39, the thermal expansion coefficients of bonds αb correlate to the valance of a bond (s), that is αb ∝ s−2. In addition, the force constant of a bond kb is related to bond valance kb ~ s (see more discussion in SI)38. The in-plane thermal strain can be expressed as \({\varepsilon }_{2{{{\rm{D}}}}}={\alpha }_{2{{{\rm{D}}}}}T=3.02\times \beta T/{({E}_{2{{{\rm{D}}}}})}^{2}\) (the unit of β is K × m2/N2). Therefore, \({\varepsilon }_{2{{{\rm{D}}}}} \sim 1/{E}_{2{{{\rm{D}}}}}^{2}\).

For 2D crystals, the flexural phonon mode (ZA) will be abnormally hardened under tensile strain (see Supplementary Fig. 2), leading to the negative mode Grüneisen parameter γ, and the negative γ of ZA mode is the main contributor to NTE40. The contribution of ZO mode is also negative but much smaller than that of ZA mode, and all the other phonon modes associated with in-plane motion have positive γ41. To examine the branch contribution of ZA modes, we employ the Grüneisen theory (GT)1, as the branch contribution cannot be obtained simply through the QHA while easily by GT. This approach demonstrates validity comparable to QHA (details in Supplementary Fig. 3) but with significantly enhanced computational efficiency. Herein, we analysed the contribution of ZA modes for 28 2D crystals to the LTEC at 500 K (α500K). Figure 3a shows that the contribution of ZA mode (∣αZA∣) is negatively correlated with D, and we fitted the relation between ∣αZA∣ and D by \(| {\alpha }_{{{{\rm{ZA}}}}}|={\zeta }_{1}\times {D}^{{\beta }_{1}}\) that the resulting β1 = −0.924 and ζ1 = 9.2 × 10−6 K\({}^{-1}/{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}^{{\beta }_{1}}\), which is similar with the descriptor S1 obtained by SISSO method. Therefore, S1 could represent the impact of thermal fluctuations on the thermal expansion. Other than the ZA branch, the contribution of the remaining phonon modes to the thermal expansion coefficient is represented as α − αZA. Here, we take the result of 500K as an example. As seen clearly from Fig. 3b that α500K − αZA negatively correlates with E2D, and the relation between α500K − αZA and E2D is fitted that \({\alpha }_{500{{{\rm{K}}}}}-{\alpha }_{{{{\rm{ZA}}}}}={\zeta }_{2}\times {E}_{2{{{\rm{D}}}}}^{{\beta }_{2}}\) (β2 = −0.545, \({\zeta }_{2}=117.49\times 1{0}^{-6}\,{{{{\rm{K}}}}}^{-1}/{({{{\rm{N}}}}/{{{\rm{m}}}})}^{{\beta }_{2}}\)), which exhibits the same trend as the descriptor S2, indicating that S2 describes the in-plane expansion of 2D materials due to the expansion of internal chemical bonds.

a The relation between the contribution of ZA mode (∣αZA∣) and bending stiffness (D). b The relation between α500K − αZA and in-plane stiffness E2D. Here α500K is LETCs at 500 K. The black dash lines in (a) and (b) are obtained by fitting. c The predicted α500K against QHA results. The black dash line is diagonal. The values of E2D, D, and α500K in (a) and (b) are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary File. Here 80% of the data are randomly selected for training and 20% for validation. Herein, we also add the data of zero thermal expansion (ZTE) 2D monolayers and the data that the LTEC is relatively small but just out of the range of ZTE on the figure.

The discovery of ZTE 2D crystals

Although the data of E can be calculated from elasticity tensors (Cij) that are included in C2DB, the data of D is absent and the calculation of the D is expansive. Therefore, we first predict the D by symbolic regression (see details in Supplementary Fig. 4). Six features associated with D are selected, including E2D, density (ρ), volume per atom (vpa), thickness (h), average bond length (abl) and bond density (bd). We trained a regression model to predict D based on these descriptors and presented the results in Supplementary Fig. 4 with the root mean squared error (RMSE) of 1.34 eV. The results would be improved if more training data was used. According to the theory of thermal expansion for bulk solids42,43, the thermal expansion is related to the volume of the unit cell (V), the isothermal compressibility (KT), that is α ~ KT/V. Therefore, we choose quantities along with E2D and D as input features to predict the LTEC at 500K (α500K) and the expression generated by symbolic regression is \({\alpha }_{500{{{\rm{K}}}}}=(14.31\times {K}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}-\frac{0.038}{D})\times {E}_{2{{{\rm{D}}}}}+14.27\times \frac{D}{V}\). Here all the quantities are just the number and the units can be found in Supplementary Table 1. The predicted α500K is plotted against the QHA results as shown in Fig. 3c. The RMSE is 1.67 × 10−6 K−1 (1.35 × 10−6 K−1) and the coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.91 (0.93) for the training (testing) set, which is accurate enough for the rough screening of ZTE. Herein, we also add the data of ZTE 2D monolayers and the data that the LTEC is relatively small but just out of the range of ZTE on the figure. The results show these data are also near the diagonal, which confirms the regression model is robust. From the expression of α500K, we observed that α500K increases with the increase of D, which is consistent with our discussion above.

According to the conclusions from the classification model, ZTE materials should possess comparable in-plane and out-of-pane modes. By using the regression model of α500K with reliable predictive results, we can screen the ZTE monolayers (see details in Fig. 4). By using the criteria of stability proposed in our previous works23,44, 1224 stable 2D crystals are selected from the C2DB20 as candidates. Then we screen 10 potential ZTE materials with \(| {\alpha }_{500{{{\rm{K}}}}}| \, < \, 2{\alpha }_{c}^{{{{\rm{ZTE}}}}}\), where \({\alpha }_{c}^{{{{\rm{ZTE}}}}}=2\times 1{0}^{-6}\) K−1. It should be noted that our criterion for rough screening is moderate considering the error of prediction model. By further Grüneisen theory and QHA verification, we find 2 ZTE 2D crystals that the α can within \(\pm {\alpha }_{c}^{{{{\rm{ZTE}}}}}\) in the middle range of temperatures (300–600 K). As shown in Fig. 5, the LTECs of ZrO2 and HfO2 are 0.47 × 10−6 K−1 and 1.80 × 10−6 K−1 at 500 K, respectively. The minimum value of the LTECs are −6.90 × 10−6 K−1 for ZrO2 and −3.16 × 10−6 K−1 for HfO2, and the LTECs are negative at low temperatures until they become positive at about 400 K (ZrO2) and 170 K (HfO2). Ultimately, they maintain ZTE behaviors over a wide temperature range.

We selected 1224 stable 2D crystals from the C2DB database according to their elastic stability, dynamical stability (only considering the phonon frequency at high symmetric points), and thermodynamic stability. Then, we identified candidate ZTE, extreme NTE (ENTE), and extreme PTE (EPTE) 2D crystals using certain criteria (∣α500K∣ < 4 × 10−6 K−1 for ZTE using the regression model, D > 8 eV and E2D < 80 N/m for EPTE, D < 1 eV for ENTE). It should be noted that our criterion for the preliminary screening of ZTE 2D crystals is set at a moderate level (\(| {\alpha }_{500{{{\rm{K}}}}}| \, < \, 2{\alpha }_{c}^{{{{\rm{ZTE}}}}}\)), considering the error of the predictive model. Following this, we performed fine screening using the Grüneisen theory and dynamical stability checking (considering the phonon frequency at full q space). Finally, the results are validated by the QHA calculations. For the fine screening of ENTE, the criteria is \({\alpha }_{\min } < -15\times 1{0}^{-6}\,{{{{\rm{K}}}}}^{-1}\), where \({\alpha }_{\min }\) is the minimum value of the LTECs at low temperature.

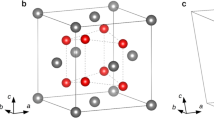

The crystal structures of ZrO2 and HfO2 are shown in Fig. 5a, b, and they are categorized as 2D transition metal oxides (TMOs), characterized by their notably dense atomic configurations and reduced thicknesses (4.96 Å for ZrO2 and 4.98 Å for HfO2). Therefore, these TMOs typically exhibit relatively large E2D (151.93 N/m for ZrO2 and 157.27 N/m for HfO2) and moderate D (3.67 eV for ZrO2 and 4.48 eV for HfO2). Apart from ZrO2 and HfO2, the LTECs of TMOs are also found to be relatively small. For example, SnO2 and MoO2 demonstrate LTECs of 4.07 × 10−6 K−1 and 4.69 × 10−6 K−1 at 500 K (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5), respectively. The ZTE behavior can also be understood by the Grüneisen parameters of ZA mode near the Γ point calculated as approximately −54 for ZrO2 and −81 for HfO2 (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6), which is much smaller than that of well-known MoS2 (≈ −10). The relatively smaller Grüneisen parameters lead to small LTEC values compared to MoS2.

The discovery of ELTE 2D crystals

Because the regression model of α500K cannot predict the data located outside of the training set, we cannot use it to predict α500K for ELTE. Here we refer to the classification model mentioned above (Fig. 2a). As for EPTE, it should possess large D and small E2D. In other words, 2D crystals composed of multiple atomic layers and weak bonds are more likely to exhibit EPTE, because D is positively correlated with h and E2D is positively correlated with kb45,46. Guided by this rule, we screened 50 stable 2D crystals with D > 8 eV and E2D < 80 N/m and calculated their LTECs using of Grüneisen theory (see Fig. 4 for the detailed process). Then we screen the potential EPTE 2D crystals by \({\alpha }_{500{{{\rm{K}}}}} \, > \, {\alpha }_{c}^{{{{\rm{ELTE}}}}}\), where \({\alpha }_{c}^{{{{\rm{ELTE}}}}}=15\times 1{0}^{-6}\) K−1, which is beyond the criteria of the high expansion groups proposed by R. Roy and co-workers (8 × 10−6 K−1)2. By further QHA verification, finally, 3 EPTE 2D crystals are found in this work and the LTECs are shown in Fig. 5j. All these materials exhibit higher LTECs than 15 × 10−6 K−1 above 500 K. Specifically, SbSe2 possesses the highest α500K (24.49 × 10−6 K−1) among these 3 EPTE materials, which is 3.27 times of the well-known MoS2 (7.48 × 10−6 K−1), while HfBi2 and HfSb2 are 2.27 and 2.65 times that of MoS2, respectively. The commonality among these EPTE materials lies in their relatively large thickness (as shown in Fig. 5c–e and Table 1), resulting in their large bending stiffness D (9.03 eV for SbSe2, 13.74 eV for HfBi2 and 10.01 eV for HfSb2). The E2D of EPTE materials is significantly lower than the well-known MoS2 (123.12 N/m) (see Table 1), and the E2D of SbSe2 (31.88 N/m) is the lowest among the three, which is approximately only one-quarter of MoS2, resulting in the highest LTEC of SbSe2 among the three materials.

Correspondingly, a small value of D combined with large E2D can lead to ENTE, indicating that 2D materials with a single atomic layer and strong covalent bonds are more likely to exhibit ENTE. Two famous 2D materials, that are h-BN and graphene with plane and hexagonal lattice, process high E2D (>200 N/m) and low D (<2 eV). We found that both graphene and h-BN demonstrate NTE behaviors below 1000 K (see LTECs in Supplementary Fig. 7). However, the minimum values of LTEC are −3.35 × 10−6 K−1 for graphene and −6.05 × 10−6 K−1 for h-BN, respectively, suggesting that they are not negative enough to be ENTE 2D crystals. Based on the discussion above, the ZA mode is the main contributor to NTE and ∣αZA∣ negatively correlates with D. Herein, we lose the screening criteria to D < 1 eV considering the rarity of 2D materials with a large E2D and small D. We screed 12 2D materials and 3 ENTE materials are found in this work (see Fig. 4). As seen from Fig. 5k, the LTECs of As2, Ge2 and Sn2 are far below −15 × 10−6 K−1 at low temperatures, and the minimum value of the LTECs (\({\alpha }_{\min }\)) are −36.39 × 10−6 K−1 for As2, −30.46 × 10−6 K−1 for Ge2 and −61.27 × 10−6 K−1 for Sn2. One point should be noted that these materials only exhibit ENTE at low temperatures. This occurs because the low-lying ZA modes with negative Grüneisen parameters will be activated firstly as the temperature increases, followed by the gradual activation of other high-frequency phonon modes, which can be shown by the temperature-dependent macroscopic Grüneisen parameters in Supplementary Fig. 8. It’s worth noting that some NTE 2D crystals, like Si2 and BP (see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 9), exhibit ZTE at high temperature. Our study specifically delves into the ZTE in the middle range of temperatures (300 to 600 K). Although the results of α500K for these two are within in ZTE range, the α at low temperature are notably negative. Consequently, we still categorize these two materials as NTE 2D crystals.

Discussion

The QHA method employed in our work considers a free-standing membrane system with infinite size. However, QHA cannot deal with the finite system, systems with boundary conditions (such as substrate effect and local constraints), or the specific entropy-driven wavy conformation. A new theory framework is lacking by now and needs to be established for further research. According to Grüneisen theory, the total thermal expansion can be regarded as the sum of all the possible phonon modes. Because either finite size or boundary conditions would modify the population of phonon modes of the system. Therefore, the results would be modified28. Because of the weak ability to resist out-of-plane deformation, the surface of 2D crystal would fluctuate at finite temperatures. The values of E2D, D would be influenced by the entropy-driven wavy conformation, which will lead to configuration and temperature-dependent results47,48. In this work, we only consider the values of E2D, D, and α for free-standing 2D crystals with infinite size. And the values of E2D and D are calculated at zero temperature with the flat configuration, which can measure intrinsic properties of bond stretch and out-of-plane deflection. Moreover, these data are easy to be accurately calculate by DFT, while obtaining the temperature-dependent results of E2D and D for extensive materials is challenging. Our results show that descriptors using the data of E2D and D at 0K can well classify PTE and NTE 2D crystals (Fig. 2), which means these data can well capture the thermal expansion at finite temperature. However, it should be noted that its success with free-standing 2D crystals of infinite size does not necessarily guarantee robustness for other systems, such as 2D monolayers with finite size or specific local geometries.

In this work, we identify the interpretable descriptors for the thermal expansion of 2D crystals from extensive data, that is E2D which measures in-plane tensile deformation, and D which measures out-of-plane bending deformation. These two mechanical descriptors can well classify the PTE and NTE 2D crystals. By utilizing high throughput calculations and the state-of-the-art symbolic regression method, these descriptors aid in the discovery of ZTE and ELTE 2D crystals. We discovered the ZTE 2D crystals or 2D Invar materials with very low α in the middle range of temperatures, following the criteria ∣α∣ < 2 × 10−6 K−1. We also discovered EPTE and ENTE 2D crystals or 2D anti-Invar with α larger or smaller than ±15 × 10−6 K−1. The understanding of thermal expansion of 2D crystals, which is dominated by the competition of in-plane and out-of-plane deformation modes, can help us to design ZTE using heterostructure or multi-layer of 2D crystals. For example, the combination of PTE and NTE 2D crystals would lead to ZTE 2D crystals (see Supplementary Fig. 10). Because of different scaling for E2D and D with layer number n (E2D ~ n1, D ~ nλ, λ > 146, see details in Supplementary Fig. 11), the multi-layer (or few-layer) 2D crystals would gradually close to ZTE if it is NTE. A good example is graphite that the absolute value of the LTEC is lower than graphene and less than 2 × 10−6 K−1 from 0 and 1000 K19. In this work, we only consider the macroscopic change of size while that local distortion of lattice, such as rotation, tilting, and collapsing motion, would lead to unusual thermal and mechanical properties2,40,49,50. Consequently, the fine design of local structures, akin to the approaches used in the field of metamaterials, emerges as a promising avenue for exploring unconventional thermal expansion behaviors. Although this work focuses on ZTE 2D crystals, the ELTE 2D materials with large expansion are also valuable for functional designs. For example, the mismatch strain between the PTE and NTE layers can induce the out-of-plane curve deformation if there is no delamination, which is promising for the design of 3D nanostructures with complex geometries51,52. In this work, we exclusively focus on mining 2D monolayers from C2DB. However, further exploration in 2DMatPedia and JARVIS databases21,22 could discover new ZTE and ELTE 2D crystals. We expect the discovery of more nanoscale materials exhibiting extraordinary thermal expansion properties that would have profound scientific significance for the design of nano-electronics.

Methods

All DFT computations were performed using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package53,54 based on the projector augmented wave (PAW) method55. The generalized gradient approximation of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof and the local density approximation exchange-correlation functionals are used56,57. The lattice parameters and atomic coordinates are optimized with the energy convergence of 10−8 eV, and the criterion for force convergence during the relaxation is 10−6 eV/Å. The cut-off energy for the plane wave is 600 eV, and a mesh grid of k-points 17 × 17 × 1 is adapted to sample the Brillouin zone(BZ). A vacuum space of ~20 Å is taken to prevent the interaction between two neighbor layers. The thermal expansion properties of 2D materials are calculated using the quasi-harmonic approximation (QHA) method58. The phonon dispersions are obtained by finite difference method using PHONOPY59. In this work, we have used a supercell size of 6 × 6 × 1 and a k-point sampling of 4 × 4 × 1. The out-of-plane transverse acoustic (ZA) mode is very soft for 2D materials and a small compressive strain may result in imaginary phonon frequencies near the Γ point. Therefore, small strains (within ± 1.5%) were employed when utilizing the QHA method. The equilibrium in-plane lattice parameters at any temperature T are determined by minimizing the Helmholtz free energy. Finally, the liner thermal expansion coefficient is defined as \(\alpha (T)=\frac{1}{a(T)}\frac{da(T)}{dT}\), where a(T) is the equilibrium lattice constant. In addition to QHA, the LTEC can also be obtained from the Grüneisen theory1, which shows efficiency and validity (details in Supplementary Fig. 3)41,49. The impact of van der Waals (vdW) dispersion corrections on the LTECs is examined by incorporating DFT-D3 (method of Grimme et al. with zero damping) and vdW-DF vdW dispersion corrections60,61. The results depicted in Supplementary Fig. 12 suggest a negligible influence on the LTECs. For ensure the reliability of our calculation results, we compare our results with available theoretical and experimental data (see details in Supplementary Fig. 13). The results show our calculation results are consistent with reported results and therefore our calculations are reliable. The bending stiffness D can be obtained by fitting the quadratic dispersion w(q) of the flexural ZA mode62, \({w}^{2}=\frac{D}{\rho }{q}^{4}\), where ρ is the areal density of mass. According to the generalized Hook’s law, the in-plane elastic constants can be calculated by applying small strains of ±1% to the equilibrium configuration, and the elastic constants Cij are derived from the second-order derivative of the total energies versus applied strain. And the data of Cij is available in the C2DB. The in-plane stiffness can be derived from the elastic constants as E2D = (C11C22 − C12C21)/C22. The compressibility KT is calculated as KT = S11 + S12. Here, S is the elastic compliance matrix, which can be obtained by calculating the inverse of stiffness matrix Cij.

Data availability

The Source Data underlying the figures of this study are available with the paper. Original data and codes created for the study will also be available on the Materials Cloud platform (https://doi.org/10.24435/materialscloud:hc-zb). All the data or scripts generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Barron, T., Collins, J. & White, G. Thermal expansion of solids at low temperatures. Adv. Phys. 29, 609–730 (1980).

Roy, R., Agrawal, D. K. & McKinstry, H. A. Very low thermal expansion coefficient materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 19, 59–81 (1989).

Sleight, A. Zero-expansion plan. Nature 425, 674–676 (2003).

Weiss, R. The origin of the invar effect. Proc. Phys. Soc. 82, 281 (1963).

Mohn, P. A century of zero expansion. Nature 400, 18–19 (1999).

van Schilfgaarde, M., Abrikosov, I. & Johansson, B. Origin of the invar effect in iron–nickel alloys. Nature 400, 46–49 (1999).

Salvador, J. R., Guo, F., Hogan, T. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Zero thermal expansion in YbGaGe due to an electronic valence transition. Nature 425, 702–705 (2003).

Lohaus, S. H. et al. A thermodynamic explanation of the invar effect. Nat. Phys. 19, 1642–1648 (2023).

Guillaume, C. Recherches sur les aciers au nickel. dilatations aux temperatures elevees; resistance electrique. C. R. Acad. Sci. 125, 235—238 (1897).

Rao, Z. et al. Machine learning–enabled high-entropy alloy discovery. Science 378, 78–85 (2022).

Yu, C. et al. Superior zero thermal expansion dual-phase alloy via boron-migration mediated solid-state reaction. Nat. Commun. 14, 3135 (2023).

Margadonna, S., Prassides, K. & Fitch, A. N. Zero thermal expansion in a Prussian blue analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 15390–15391 (2004).

Wang, S., Liu, X. & Zhou, P. The road for 2D semiconductors in the silicon age. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106886 (2022).

Wu, F. et al. Vertical MoS2 transistors with sub-1-nm gate lengths. Nature 603, 259–264 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Two-dimensional materials for next-generation computing technologies. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 545–557 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Two-dimensional devices and integration towards the silicon lines. Nat. Mater. 21, 1225–1239 (2022).

Plechinger, G. et al. Low-temperature photoluminescence of oxide-covered single-layer MoS2. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) 6, 126–128 (2012).

Sevik, C. Assessment on lattice thermal properties of two-dimensional honeycomb structures: graphene, h-BN, h-MoS2, and h-MoSe2. Phys. Rev. B 89, 035422 (2014).

Mounet, N. & Marzari, N. First-principles determination of the structural, vibrational and thermodynamic properties of diamond, graphite, and derivatives. Phys. Rev. B 71, 205214 (2005).

Haastrup, S. et al. The computational 2D materials database: high-throughput modeling and discovery of atomically thin crystals. 2D Mater. 5, 042002 (2018).

Zhou, J. et al. 2DMatPedia, an open computational database of two-dimensional materials from top-down and bottom-up approaches. Sci. Data 6, 1 (2019).

Choudhary, K. et al. The joint automated repository for various integrated simulations (JARVIS) for data-driven materials design. NPJ Comput. Mater. 6, 1 (2020).

Qian, C., Zhou, K., Xiong, Y., Chen, X. & Li, Z. High-throughput discovery and investigation of auxetic two-dimensional crystals. Chem. Mater. 34, 4344–4354 (2022).

Shao, Q., Li, R., Yue, Z., Wang, Y. & Gao, E. Data-driven discovery and understanding of ultrahigh-modulus crystals. Chem. Mater. 33, 1276 (2021).

Gao, E., Yuan, X., Nielsen, S. O. & Baughman, R. H. Exploring the bounds on the Young’s modulus and gravimetric Young’s modulus. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 014044 (2022).

Li, R., Shao, Q., Gao, E. & Liu, Z. Elastic anisotropy measure for two-dimensional crystals. Extreme Mech. Lett. 34, 100615 (2020).

Shiga, M. Invar alloys. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 1, 340–348 (1996).

Gao, W. & Huang, R. Thermomechanics of monolayer graphene: rippling, thermal expansion and elasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 66, 42–58 (2014).

Pozzo, M. et al. Thermal expansion of supported and freestanding graphene: lattice constant versus interatomic distance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 135501 (2011).

Chen, S. & Chrzan, D. Monte Carlo simulation of temperature-dependent elastic properties of graphene. Phys. Rev. B 84, 195409 (2011).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Ouyang, R., Curtarolo, S., Ahmetcik, E., Scheffler, M. & Ghiringhelli, L. M. Sisso: a compressed-sensing method for identifying the best low-dimensional descriptor in an immensity of offered candidates. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 083802 (2018).

Weiner, J. H. Statistical mechanics of elasticity (Courier Corporation, 2012).

Chen, Y., Ouyang, W., Zhou, K., Qin, H. & Liu, Y. Finite temperature mechanics of multilayer 2d materials. Extreme Mech. Lett 52, 101612 (2022).

Ahmadpoor, F., Wang, P., Huang, R. & Sharma, P. Thermal fluctuations and effective bending stiffness of elastic thin sheets and graphene: A nonlinear analysis. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 107, 294–319 (2017).

Pathria, R. K. Statistical mechanics (Elsevier, 2016).

Schelling, P. & Keblinski, P. Thermal expansion of carbon structures. Phys. Rev. B 68, 035425 (2003).

Brown, I. D., Dabkowski, A. & McCleary, A. Thermal expansion of chemical bonds. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci 53, 750–761 (1997).

Megaw, H. D. The thermal expansion of crystals in relation to their structure. Zeitschrift für Kristallographie-Crystalline Materials 100, 58–76 (1939).

Mondal, S. & Datta, A. Negative thermal expansion induced in tri-graphene and t-graphene by the rigid-unit modes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 16703–16707 (2022).

Ge, X.-J., Yao, K.-L. & Lü, J.-T. Comparative study of phonon spectrum and thermal expansion of graphene, silicene, germanene, and blue phosphorene. Phys. Rev. B 94, 165433 (2016).

Hiki, Y. Higher order elastic constants of solids. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 11, 51–73 (1981).

Dugdale, J. & MacDonald, D. The thermal expansion of solids. Phys. Rev. 89, 832 (1953).

Tian, S. et al. Investigation and understanding of the mechanical properties of MXene by high-throughput computations and interpretable machine learning. Extreme Mech. Lett. 57, 101921 (2022).

Wyatt, B. C., Rosenkranz, A. & Anasori, B. 2D MXenes: tunable mechanical and tribological properties. Adv. Mater. 33, 2007973 (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Bending of multilayer van der Waals materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 116101 (2019).

Qin, H., Sun, Y., Liu, J. Z. & Liu, Y. Mechanical properties of wrinkled graphene generated by topological defects. Carbon 108, 204–214 (2016).

Jiang, J.-W., Wang, B.-S., Wang, J.-S. & Park, H. S. A review on the flexural mode of graphene: lattice dynamics, thermal conduction, thermal expansion, elasticity and nanomechanical resonance. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 27, 083001 (2015).

Li, Q., Zhou, J., Liu, G. & Wan, X. Extraordinary negative thermal expansion of monolayer biphenylene. Carbon 187, 349–353 (2022).

Miller, W., Mackenzie, D., Smith, C. & Evans, K. A generalised scale-independent mechanism for tailoring of thermal expansivity: positive and negative. Mech. Mater. 40, 351–361 (2008).

Xu, W. et al. Ultrathin thermoresponsive self-folding 3D graphene. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701084 (2017).

Huang, Q. et al. Shell microelectrode arrays (MEAs) for brain organoids. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq5031 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048 (1981).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tanaka, I. & Hug, G. First-principles phonon calculations of thermal expansion in Ti3SiC2, Ti3AlC2, and Ti3GeC2. Phys. Rev. B 81, 174301 (2010).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134106 (2008).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements h-pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Dion, M., Rydberg, H., Schröder, E., Langreth, D. C. & Lundqvist, B. I. Van der Waals density functional for general geometries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 246401 (2004).

Gao, E. & Xu, Z. Thin-shell thickness of two-dimensional materials. J. Appl. Mech. 82, 121012 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12102324 and 12325204) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022T150519), and Scientific Research Program of Shaanxi Province (2023JC-XJ-02). The work was carried out at the National Supercomputer Center in Tianjin, and the calculations were performed on TianHe-1(A). We sincerely thank Prof. Jin-Wu Jiang from Shanghai University for his insightful comments on our work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Z. conceived the project. K.Z. and Y.L. supervised the research. S.T. and K.Z. carried out the DFT calculations and theoretical analysis. S.T., K.Z., W.Y., and Y.L. co-wrote the paper, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bohayra Mortazavi, Zhao Qin, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, S., Zhou, K., Yin, W. et al. Machine learning enables the discovery of 2D Invar and anti-Invar monolayers. Nat Commun 15, 6977 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51379-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51379-6

This article is cited by

-

PAH101: A GW+BSE Dataset of 101 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) Molecular Crystals

Scientific Data (2025)