Abstract

The assembly of polymers at liquid-liquid interfaces offers a promising strategy for fabricating two-dimensional polymer films. However, a significant challenge arises when the polymers lack inherent interfacial traction. In response, we introduce an approach termed chaperone solvent-assisted assembly. This approach utilizes a target polymer, X, along with three solvents: α, β, and γ. α and β are poor solvents for X and immiscible with each other, while γ is a good solvent for X and miscible with both α and β, thus serving as the chaperone solvent. The cross-interface diffusion of γ induces the assembly of interfacially nonactive X at the α-β interface, and this mechanism is verified through systematic in situ and ex situ studies. We show that chaperone solvent-assisted assembly is versatile and reliable for the interfacial assembly of polymers, including those that are interfacially nonactive. Several practical applications based on chaperone solvent-assisted assembly are also demonstrated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the natural world, many materials exhibit interfacial activity, enabling them to spontaneously arrange themselves at the liquid interface. This process is known as liquid interfacial assembly, pervasive in both natural and industrial contexts1,2. In recent years, this natural phenomenon has garnered significant attention in material synthesis and fabrication. The inherent properties of liquids, particularly their molecular mobility, make interfacial assembly a promising bottom-up approach for synthesizing two-dimensional (2D) or quasi-two-dimensional (quasi-2D) polymer films. In view of this, liquid interfacial assembly approaches, including surfactant-directed interfacial polymerization3,4,5, and pair-interaction induced interfacial assembly6,7, have been reported to fabricate functional 2D/quasi-2D polymer films. Such protocols are highly effective in creating large-sized, defect-free, and structurally tunable films. These advantages make it particularly useful in emerging fields like photovoltaics, soft electronics, and biomedicine3,8,9,10. Despite its promise, the main obstacle preventing the widespread adoption of the liquid interfacial assembly approach is its limited efficacy when dealing with polymers or monomers lacking inherent interfacial activity.

In response to this challenge, we propose the chaperone solvent-assisted assembly (CSAA) approach as a universal solution to realize the interfacial assembly for fabricating polymer films based on polymers, even for those lacking inherent interfacial activity at the liquid interface. Unlike the conventional interfacial assembly approach driven by the amphiphilic nature of the target polymer or primer, CSAA uses solvent diffusion to initiate the interfacial assembly of the polymer, significantly broadening its applicability in fabricating various 2D or quasi-2D polymer films.

In this work, we demonstrate a CSAA process, with assistance from the cross-interface diffusion of chaperone solvent, to assemble polymers at the liquid interface between two poor solvents and realize the preparation of 2D/quan-si 2D polymer films. The CSAA process requires only three solvents (α, β, and γ) for the target polymer (X). α and β are immiscible and poor solvents for X, while γ is miscible with both α and β, acting as a chaperone solvent for X (Fig. 1a). When solvents α and β come into contact, a liquid interface is formed. As shown in Fig. 1b, by introducing a solution of X dissolved in γ into either α or β, the diffusion of γ across the α-β interface spontaneously occurs due to the concentration gradient of γ. This results in X being transported to and assembled at the α-β interface. In this article, we elaborate on the mechanism, universality, and tunability of the CSAA approach for the interfacial assembly of polymers regardless of their interfacial activity. Finally, we also demonstrate the promising applications of CSAA in fabricating 2D or quasi-2D polymer films.

a Schematic illustration of the CSAA process. Chaperone solvent γ forms micelles with target polymer X in the oil phase, then the micelles diffuse towards the α-β interface due to the concentration gradient of chaperone solvent γ. Only amphiphilic chaperone solvent γ diffuses across the interface while target polymer X is trapped at the interface, forming the 2D polymer film. Purple entangled line: target polymer X; green species: chaperone solvent γ. b Ternary-composite phase diagram of the mixing solvent system containing toluene/water /DMSO.

Results

Chaperone solvent-assisted assembly and its demonstration

To underscore the practicality of CSAA, we initially focused on a model system centered around the target polymer X—polyacrylonitrile (PAN). The associated solvents, α, β, and γ, correspond to toluene, water, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in that order (Fig. 1a). In this ternary-composition system, the resultant mixture can exist as an emulsion, a single-phase liquid, or a two-phase liquid, as previously reported11. Herein, we conducted CSAA in the two-phase liquid region as mapped out in the ternary-phase diagram (Fig. 1b).

The addition of materials at the liquid interface induces a change in interfacial tension (IFT)12. To validate the idea of CSAA, we first conducted a pendent-drop experiment—a conventional approach to quantify the change in IFT. Figure 2a shows the IFT of the water-toluene interface as a function of time, where the toluene phase contains different PAN-DMSO solutions. In this work, the content of PAN in the PAN-DMSO solution is denoted as [PAN]DMSO, while the content of the PAN-DMSO solution in the oil phase is denoted as [DMSO]oil. The results clearly indicate that an increase in [PAN]DMSO, with a fixed DMSO amount, leads to a more pronounced reduction in IFT, demonstrating the existence of interfacial assembly of PAN molecules at the water-toluene interface.

a Oil-water IFT evolution versus [PAN]DMSO, where the [DMSO]oil is identical for every curve. b, c Pendent-drop retraction of oil droplet: b, DMSO/toluene mixture without PAN; c, Toluene mixed with PAN-DMSO solution, [PAN]DMSO = 4 mg mL-1. d Snapshots in chronological order showing the visible diffusion of chaperone DMSO across the oil-water interface and the resultant interfacial assembly of PAN. The oil droplet is toluene mixed with PAN-DMSO solution, where [PAN]DMSO = 1 mg mL-1, [DMSO]oil = 33.66 wt.%, outer phase is water. e–g The assembly of toluene droplets with different [DMSO]oil (e) 15.34 wt.% and (g) 1 wt.%. The amount of PAN molecules in both systems is the same, as shown in (f). h Demonstration of IC dependance on aging time. i IC evolution influenced by the [DMSO]oil. The aging time for all measurements is 1200 s. The dashed line is to guide the eye. j Influence of [PAN]DMSO on IC. Inset, interfacial assembly is indicated by the wrinkling when withdrawing the oil droplet. All scale bars, 1 mm. Values in h and i represent the mean, and the error bars represent the SD of the three measured values of each sample (n = 3). The IC of three replicate samples was measured by an identical tensiometer method in h.

Since PAN is not soluble in both water and toluene, if it assembles at the water-toluene interface, its binding affinity to the liquid interface should be strong and is expected to bear mechanical interfacial compression to some extent. After the time-dependent IFT measurements, we withdrew the liquid from the pendent drop to intentionally apply interfacial compression. As shown in Fig. 2b, no wrinkles were observed in the case where PAN is absent, whereas interfacial wrinkles were observed in the case with a 4 mg mL-1 PAN-DMSO solution added to toluene (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Movie 1). This also indicates that CSAA can promote the interfacial assembly of PAN at the water-toluene interface, even though PAN has no inherent interfacial activity and is not soluble in both liquids. Wrinkles observed during the interfacial compression indicate the elastic behavior of the self-assembled interfacial PAN film. In this scenario, the interfacial viscoelasticity was measured by a dilatational deformation with tensiometry oscillation. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the storage moduli (E′) and loss moduli (E″) against frequency ω (0.01–0.658 Hz), where E′ is greater than E″ across the entire frequency range. The results show that the interfacial PAN film is dominated by elastic behavior (E′), thus affording the wrinkles upon the interfacial compression. In addition, the higher moduli indicate the mechanical enhancement and increased interfacial rigidity caused by the interfacial PAN film compared to the pristine liquid interface. This elastic interfacial film lays the foundation for applications such as all-liquid 3D printing.

The CSAA process hinges on the diffusion of DMSO across the oil-water interface, serving to transport PAN to the interface. To better understand this diffusion process, we injected an oil droplet into the water phase and recorded the entire CSAA process with a high-speed camera (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Movie 2). The refractive index difference between DMSO and water made the DMSO flow easily observable. In the initial stages, DMSO diffusion from the oil droplet into the water phase was evident, creating a DMSO layer on the oil droplet’s surface, facilitating phase separation, and transporting PAN to the oil-water interface. Toward the end of the injection, the needle tip was the only location showing visible DMSO due to its higher density compared to water, resulting in excess PAN precipitation at the needle tip, as seen in the chronological images (Fig. 2d). Reducing the droplet volume led to observable interfacial wrinkles (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Movie 2), further confirming that DMSO acted as a chaperone, transporting PAN to the interface, and enabling its assembly. Note it is the concentration gradient of the chaperone solvent that triggers CSAA, CSAA is expected to be valid if the PAN-DMSO solution is originally added into the water phase. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Movie 3, the interfacial assembly of PAN happened as expected when DMSO diffused from the water to the oil phase, emphasizing the critical role of the chaperone solvent diffusion.

Impact of the cross-interface diffusion of the chaperone solvent

CSAA heavily relies on the cross-interface diffusion of the chaperone solvent to transport the target polymer to the liquid interface. In this section, we investigated the impact of such diffusion on the interfacial assembly of the target polymer. Previously, we used interfacial wrinkles as evidence to demonstrate the existence of interfacial assembly of the target polymer X, i.e., PAN. Here, we used the ratio of the pendant drop’s volume at which the first visible wrinkle appeared to the initial drop’s volume to quantify the interfacial coverage of the PAN molecules at the liquid interface, denoted as IC. Without specifying, all pendant drops were aged for 1200 seconds to allow sufficient interfacial assembly. Figure 2e–g are snapshots of two different pendant drops before withdrawal and during withdrawal when wrinkles first appeared. While both pendant drops have the same amount of PAN molecules, different amounts of DMSO seem to lead to dramatic differences in the IC value (Fig. 2f). The enhancement in the IC value is about three times when the DMSO concentration is increased by about 15 times. The results imply that the cross-interface diffusion of the chaperone solvent not only initiates the interfacial assembly of PAN but also plays an important role in dictating the interfacial film formation. We, therefore, further explored how DMSO affects the temporal evolution of the interfacial film formation. The affinity of DMSO to both toluene and water results in the decrement of IFT (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The CSAA consists of several processes, including the forced diffusion of target polymer X by the chaperone solvent γ, the subsequent de-solvation, and the interfacial assembly of target polymer X. The interplay between these processes makes it difficult to describe the CSAA process using an existing physical model. Thus, we studied the influence of different variables on the CSAA process. As shown in Fig. 2h, Supplementary Fig. 5, and Movie 4, prolonged aging time led to an increase in IC until reaching a saturated value. By fitting the time-dependent IC data with an exponential function, we obtained insights into the underlying mechanism of CSAA. Taking [DMSO]oil = 6.26 wt. % as an example, the data can be fitted into an exponential scaling law, with an R-squared value of 0.979, indicating a good and appropriate fit. The fitting for all experiments showed similar results. This scaling law indicates the self-limited IC evolution over time, corresponding to the plateau of the curve. For [DMSO]oil = 6.26 wt. %, it took the interface more than 4500 seconds to get 50% covered; however, when the [DMSO]oil was increased by a factor of ~5, it took only around 100 seconds to reach almost 100% coverage. From the fitted curve, a time constant τ can be obtained. When [DMSO]oil was increased from 6.26 to 33.66 wt.%, τ decreased from approximately 500 s to around 29 s (Supplementary Fig. 6). Another representation of IC data with a fixed aging time of 1200 s is shown in Fig. 2i and Supplementary Movie 5. The results unambiguously demonstrate that more chaperone solvents significantly facilitate the interfacial assembly of the target polymer.

It should be noted that the extent of the impact of the chaperone solvent’s concentration also varies with the change in the concentration of the target polymer X, i.e., PAN in the model system. Figure 2j shows the IC values at different [PAN]DMSO as well as [DMSO]oil. A general trend from these results is that when PAN is insufficient, the impact of the concentration of the chaperone solvent on the interfacial assembly formation rate is much more pronounced. However, if [PAN]DMSO is greater than 1 mg mL-1, no matter how much PAN is added, no significant effect is observed. These results clearly show the synergic effect of both target polymer X and the chaperone solvent γ.

In all discussed experiments so far, the cross-interface diffusion was initiated by the concentration difference of the chaperone solvent, i.e., DMSO, on both sides of the liquid interface. Since the working principle of CSAA is expected to be independent of what drives the cross-interface diffusion, we then wonder whether we can induce the interfacial assembly of PAN through the cross-interface diffusion of DMSO driven by other sources. It is known that even in the equilibrium condition, thermal fluctuations would also lead to the bidirectional flow of molecules across the liquid interface. The long-time equilibrium experiments (Supplementary Fig. 7) confirm our hypothesis and indicate that cross-interface diffusion of the chaperone solvent is only a premise of CSAA.

Formation of interfacial assemblies

With bulk interfacial measurements, including IFT and IC measurements, we offer some macroscopic insights into the interfacial assembly of the target polymer X at the liquid interface, while the molecular-level workings of CSAA and the structure of the exhibited interfacial assemblies remain unclear. In this section, we aim to elucidate the underlying mechanism of CSAA in detail. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were carried out to reveal the cross-interface diffusion process of the chaperone solvent DSMO. The cross-interface diffusion of DMSO relies on its amphiphilicity, which can be identified in its molecular structure (Fig. 1b). Here, we employed MD simulation to show the solvation of amphiphilic DMSO in water and toluene. The simulation result is consistent with previous experiments: stable solutions can be obtained by mixing DMSO with water and toluene (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b).

As shown in Fig. 3a–c, Supplementary Fig. 8c–e, and Movie 6, driven by concentration differences, DMSO diffuses from the oil phase to the water phase and accumulates near the oil-water interface. The enrichment of DMSO at the water-toluene interface is believed to be attributed to the finite amphiphilic nature of DMSO. These results also suggest that the effect of the chaperone solvent DMSO on CSAA is twofold: (1) cross-interface diffusion transports PAN to the water-toluene interface, (2) the enrichment of DMSO at the liquid interface facilitates the interfacial assembly in addition to the assembly caused by the poor solubility of PAN in both liquid phases.

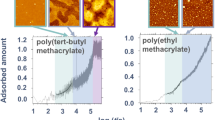

a MD simulations revealing the diffusion process of DMSO from the oil phase (colored in yellow) to the water phase (colored in blue). b, c Spatial distribution of atoms, denoted as n, corresponding to DMSO molecules, at the end of the diffusion: b the density of DMSO along the direction vertical to the interface, and c the density distribution of DMSO in the water-toluene system. d AFM image of the interfacial film formed by PAN particles. e DLS results showing size-dependence of PAN particles on contents of chaperone DMSO. The scale bar is 200 nm.

To illustrate the structure of the interfacial assemblies of PAN at the liquid interface, we imaged the interfacially assembled PAN film being transferred to a solid substrate by atomic force microscopy (AFM). Surprisingly, instead of forming smooth thin films, the PAN film formed via CSAA is composed of many PAN spheres, as shown in Fig. 3d. We anticipated that these PAN spheres were already formed in the liquid phase assisted by the chaperone solvent before the occurrence of the interfacial assembly. To test this hypothesis, we measured the PAN-DMSO-Toluene solution with different [DMSO]oil using dynamic light scattering (DLS). DLS allowed us to identify the size of any substrates in the range of nanometers to micrometers. It is clear from Fig. 3e that, by simply increasing DMSO concentration, different-sized objects were observed in the PAN-DMSO-Toluene solution. The DLS results (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 9) indicate that PAN molecules dissolved in toluene, a poor solvent of theirs, with a layer of DMSO molecules. These structures are reminiscent of the micelle formation in a saturated surfactant solution13,14. It is noticed that the increment of [DMSO]oil not only decreases the sizes of PAN particles but also narrows down the size distribution of these particles. It is worth noting that CSAA provides a promising avenue to fine-tune the morphology of the interfacially assembled polymer thin film.

Universality of CSAA

Many conventional interfacial assembly strategies strongly rely on intermolecular interactions, such as electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and more, making them particularly sensitive to external environments15,16,17,18,19. One major advantage of CSAA is that it does not involve any intermolecular interactions. Therefore, in principle, CSAA should exhibit excellent tolerance to harsh environments, which is always a challenge for interfacial assemblies involving various intermolecular interactions. In this regard, we measured the interfacial assembly of PAN molecules at the water-toluene interfaces assisted by DMSO in different environments, such as varied pH values and ionic strength. The results unambiguously demonstrate the robust performance of CSAA in harsh conditions, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Fig. 11, and Movie 7.

The primary advantage of CSAA lies in its straightforward construction and broad applicability to various interfacially nonactive polymers. CSAA centers around a target polymer X and only requires three additional solvents, i.e., α, β, and γ. Therefore, CSAA is expected to be a universal approach for the interfacial assembly of polymers lacking inherent interfacial activity. To further showcase the universality of CSAA, we explored several other model systems, as shown in Fig. 4, Table 1, and Supplementary Movie 8. These systems are suitable for both traditional and specially synthesized functional polymers, including, but not limited to, PVAc, PVC, PS, and PDI-N-DAN, among others. Our results underscore CSAA’s capability to facilitate the reliable interfacial assembly of a diverse range of polymers, offering effective strategies for synthesizing 2D polymer films.

Here we attempt to unleash the power of CSAA by demonstrating the interfacial assembly of a popular thermo-responsive polymer at the liquid interface and exploring its potential in controlling mass transfer across the liquid interface. The target polymer X is poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM), and the associated solvents are water, toluene, and methanol (MeOH), where MeOH serves as the chaperone solvent. PNIPAM can undergo a reversible phase transition from a water-soluble hydrated state to an insoluble dehydrated state around 32 °C, leading to an expansion in size upon decreasing the temperature20. Given a liquid interface with pre-assembled PNIPAM via CSAA, if one decreases the temperature, the spherically shaped PNIPAM would expand at the liquid interface and reduce the inter-particle distance, as depicted in Fig. 5a. This temperature-responsive interfacial PNIPAM film then served as an interfacial shutter that could potentially control any cross-interfacial diffusion process. To visualize this process, we used rhodamine 6 G (R6G) as the tracer. Supplementary Fig. 13 and Fig. 5b show the snapshots of three different samples when an R6G solution was added to the toluene phase, where PNIPAM had already assembled at the liquid interface for a sufficient time. After some time, it is evident that the diffusion front ranks from long to short are sample 3, sample 1, and sample 2. Sample 3 has no interfacially assembled PNIPAM; therefore, R6G can freely diffuse across the interface without much resistance. Sample 1 and sample 2 have pre-assembled PNIPAM at the water-oil interface and slowed down the cross-interface diffusion process. Notably, much more sluggish diffusion was observed for sample 2. This is because all PNIPAM spheres were swelled at the water-oil interface at ~0 °C and significantly blocked the diffusion of R6G across the liquid interface. A quantitative UV–Vis measurement revealed this temperature-controlled cross-interface diffusion process. As shown in Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 14, the absorbance values for samples are in accordance with the visible color in Fig. 5b.

a Schematic illustration for the mechanism of temperature-responsive PNIPAM film acting as a switch to control the diffusion of R6G. Blue entangled line: PNIPAM microgel; green sphere: R6G molecule. b The control experiments show the tunable diffusion by temperature-responsive PNIPAM film. Sample 1: oil-water interface with pre-assembled PNIPAM at constant temperature of 40 °C; sample 2: oil-water interface with pre-assembled PNIPAM and temperature decreases from 40 °C to 0 °C; sample 3: bare interface without pre-assembled PNIPAM at constant temperature of 40 °C, oil phase in all samples is MeOH/toluene, in which [MeOH]oil = 18.6 wt.%. c Comparison of UV–Vis spectrum and absorption intensity of the different water phases, which are obtained from different systems after the on-off test of the interfacial temperature-responsive switch. d Diffusion behavior of R6G across the oil-water interface, where the diffusion speed is represented by the absorption intensity after the diffusion is finished, which is obtained by UV–Vis. Values in d represent the mean, and the error bars represent the SD of the three measured values of each sample (n = 3). The absorbance of three replicate samples was measured by an identical method.

It is noticed that lower temperatures can potentially suppress Brownian motion and lead to a retarded diffusion process. To rule out any non-interfacial related temperature-dependent diffusion effect, we quantitatively measured the cross-interface diffusion of R6G at different temperatures. Figure 5d shows the amount of R6G detected in the water phase at a fixed transfer time quantified by the UV–Vis characteristic absorbance of R6G. There is a transition in the plot from around 35 °C to 47 °C, which is close to the phase transition temperature of PNIPAM. The non-linear temperature dependence confirms the interfacial assembly-gated cross-interface mass transfer process realized via CSAA.

One-step fabrication of functional polymer thin films

The assembly of polymers at the liquid interface has emerged as a promising approach to fabricating large-sized, defect-free, and structure-tunable functional polymer thin films, garnering considerable attention in recent years3,21. Here, we aim to harness the potential of CSAA in the construction of functional polymer thin films, even for those lacking inherent interfacial activity.

First, we synthesized a series of perylene diimide (PDI) based co-polymers and demonstrated how CSAA could be employed to fabricate these photosensitive polymers into photoelectric devices. To evaluate the photoelectric performance of these PDI-N-DEN polymer thin films, the as-prepared PDI-N-DEN film via CSAA was loaded onto an interdigital electrode and measured under different illumination conditions, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 15a. The PDI unit in the PDI-N-DEN polymer serves as the electron host unit, characterized by its low-lying lowest unoccupied molecular orbital and high electron affinity (Supplementary Fig. 15b). Upon light illumination, charge transfer from DEN to the PDI unit is induced, resulting in the generation of photocurrent. Figure 6a shows photoelectric current measurements of the PDI-N-DEN-based photoelectric detector under alternating UV light illumination at various bias voltages. Figure 6b depicts images of a bare 2-inch quartz wafer and another wafer with a transferred PDI-N-DEN polymer thin film fabricated via CSAA. The uniform color of the transferred film attests to the good structural integrity of the functional polymer thin film, indicating its promise for the fabrication of photoelectric devices. The photoelectric current measurements demonstrate the good stability of the device, evidenced by no noticeable decay in photocurrent. Even after 80 cycles, the photoelectric currents exhibit a symmetric profile with onset and offset response times of around 230 ms (Supplementary Fig. 15c and Fig. 6c).

a Performance of as-fabricated photoelectric detector with PDI-N-DEN film active layer, which is obtained by CSAA. In every duty cycle, for light signal Ton = 5 s while Toff = 5 s. Inset: Zoom-in figure corresponding to the dashed line marked region. b Photograph of wafer-sized polymer film prepared by CSAA. Left, picture of wafer-sized PDI-N-DEN film, which is prepared by CSAA and then transferred to a quartz wafer. Right, picture of a bare quartz wafer as a comparison. c The response time of the photoelectric detector after being operated for 800 s. d–f AFM images showing the microstructures of PDI-N-DEN films prepared by CSAA, in which the volumetric ratios of toluene to TFE are 2.5, 5, and 7, respectively. g The response time of the prepared device corresponding to samples in d–f. Values in g represent the mean, and the error bars represent the response time of measured values of the same sample in different cycles (n = 5). The response time of every sample was measured by an identical method. h Comparison of the response time for the photodetectors made from PDI derivatives by this work and other reports37,38,39,40,41,42,43. i The synergy effect of [DMSO]oil and [PAN]DMSO on the IC. The increment of either [DMSO]oil or [PAN]DMSO contributes to the increase of IC. j Sequential snapshots of the all-liquid 3D printing process, solvent blue is added into the oil phase to emphasize the oil spiral. Printing parameters are as follows: needle size−14 gauges (1.6 mm), flow rate 500 μL min-1. Scale bars: d–f 500 nm; i 2 cm.

As discussed in the previous section about the morphology control in CSAA, we can fine-tune the microstructure of interfacial assemblies by simply varying the ratio of chaperone solvent γ. Herein, we further demonstrate the significant impact of morphology on the performance of the PDI-N-DEN-based photoelectric devices. Figure 6d–f shows the AFM images of transferred PDI-N-DEN films fabricated via CSAA with different toluene/2,2,2-Trifuoroethanol (TFE) ratios, and Fig. 6g shows the corresponding photoelectric response time. It is evident from Fig. 6d–f that different PDI-N-DEN particles are observed, consistent with the study in the previous section. Importantly, the results reveal a strong correlation between the particle size and photoelectric response time. We observed a faster response time for the PDI-N-DEN polymer thin film with large particles, suggesting that larger polymer particles better-facilitated charge transport because of the reduced boundary density.

Finally, we compared the photoelectric performance of the PDI-N-DEN-based photoelectric detector with the literature, as shown in Fig. 6h. The performance of our devices demonstrates the feasibility and reliability of CSAA for the fabrication of functional polymer thin films for electronic devices.

All-liquid 3D printing

In recent years, all-liquid 3D printing has garnered significant attention in the fields of microfluidics, precision medicine, and food processing22,23,24. Regardless of the form of all-liquid 3D printing, such as water-in-oil, oil-in-water, or water-in-water, most approaches strongly rely on post-processing treatments, such as crosslinking and interfacial polymerization, to solidify the printed structures. Here, we demonstrate how CSAA can be utilized for all-liquid 3D printing by employing 2D jamming of interfacially assembled polymer particles without any post-processing treatments.

We utilized a modified model system consisting of the target polymer PAN and associated solvents: water, dichloromethane (methylene chloride) (DCM), and DMSO. To facilitate 3D printing, 40 wt.% poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) was added to the water phase to increase the viscosity of the dispersion phase. When the DCM phase, with added DMSO and PAN, was injected into the water phase, the interfacial assembly of PAN at the water-oil interface spontaneously occurred via CSAA. Despite the tendency of IFT to reshape the printed structures into spheres, as spheres have the lowest interfacial area, the interfacial PAN film is mechanically stiff enough to overcome such reshaping tendencies and lock down the printed structures, as indicated by the interfacial assembly dynamics in previous studied model system (Fig. 6i). Therefore, to maintain the printed structure, a fast interfacial assembly rate is crucial. Thanks to the fast interfacial assembly rate of CSAA, we were able to print oil (DCM) tubes inside a water bath with optimized printing parameters. The successful printing of the oil thread is displayed in Fig. 6j and Supplementary Movie 9. It is noteworthy that the entire printing process only took 30 seconds, considerably faster than other all-liquid interface methods requiring post-processing treatments25,26,27. The printed structure showed good structural stability after being settled for three days (Supplementary Fig. 16).

In conclusion, we proposed a universal CSAA method to assemble polymers at liquid interfaces, regardless of the interfacial activity of polymers. CSAA relies on the cross-interface diffusion of the chaperone solvent; therefore, it is also feasible for polymers that lack inherent interfacial activity. Through systematic experimental interfacial measurements along with molecular dynamics simulations, we unveiled the underlying mechanism of CSAA and demonstrated morphology control through the cross-interface diffusion process. By varying external environments, we showed that CSAA had excellent resistance to pH and ionic strength, making it particularly useful in harsh environments. Furthermore, we explored the universality of CSAA by investigating additional model systems, including both conventional functional polymers and those synthesized in this project. Finally, we demonstrated the applications of CSAA, including the synthesis of thermo-responsive interfacial membranes, the fabrication of photoelectric polymer thin films, and the construction of all-liquid 3D printing. All in all, CSAA provides a universal and promising platform for the interfacial assembly of polymers and a reliable approach for the interfacial assembly of polymers as well as fabricating 2D/quasi-2D polymer films, which can offer guidance for the design of various functional films.

Methods

Materials

The following chemicals were used as received:

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, ACS reagent, >99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich), Toluene (ACS, AQA), 2,2,2-Trifuoroethanol (TFE, 99.5%, Aladdin, China), Polyacrylonitrile (PAN, average Mw 85,000, Macklin, China), Poly (vinyl acetate) (PVAc, approx. M.W.100,000, Macklin, China), Methanol (MeOH, HPLC, RCI LABSCAN), Rhodamine 6G (R6G, AR, M.W. 479.01, Macklin, China) Milli Q DI water (18.2 MΩ) Petroleum ether (AR, bp 60–90 °C, Aladdin, China) dichloromethane (methylene chloride) (DCM, AR, Dieckmann, China), Polyethylene glycol (PEG, M.W. 20,000, Macklin, China), Polyvinyl chloride (PVC, Aladdin, China), Polystyrene (PS, Aladdin, China), Ethanol (EtOH, Aladdin, China), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, Aladdin, China), Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM, Macklin, China).

Construction of the typical CSAA model system

In this work, a typical CSAA system was constructed as follows: PAN was dissolved into DMSO (chaperone solvent γ), then PAN-DMSO solution was mixed with toluene (solvent α) to form the oil phase. To describe the composition of the oil phase, the concentration of PAN in DMSO and the content of DMSO in mixed oil were denoted as [PAN]DMSO and [DMSO]oil, respectively. Then the oil phase was added to the top of the water phase (solvent β) to create an oil-water interface and allow the diffusion-induced interfacial assembly to proceed.

Pendent-drop experiment for the measurement of IFT and IC

The pendent-drop experiment was carried out by a tensiometer (Dataphysics, OCA15EC) to investigate the diffusion of DMSO and the IFT evolution of the oil-water interface. To analyze the diffusion of DMSO, an oil droplet ([PAN]DMSO = 1 mg mL-1, [DMSO]oil = 55.92 wt.%) was slowly injected into the water phase with a speed of 0.5 μL s-1. A high-speed camera monitored and recorded the injection process, as shown in Supporting Movie 2. The step motor attachment of the tensiometer controlled the retraction of a droplet.

Seawater was prepared by dissolving sea salt into DI water with 35‰ content to evaluate the influence of ionic strength. The obtained seawater was used as the outer phase for IC measurement. The oil phase was typically injected into the seawater, and the CSAA was allowed for 1200 s. Then, the droplet volume was withdrawn until the first wrinkle was observed. The IC can be calculated using the ratio of the pendant drop’s volume at which the first visible wrinkle appeared to the initial drop’s volume.

Atomic force microscopy characterization of PAN film prepared by CSAA

Cypher ES (Oxford) was used to characterize the morphology of the interface film. The Langmuir-Blodgett (L-B) method was used to transfer the PAN film onto a silicon wafer for further characterization28. In this process, a homemade PTFE L-B trough was used to carry out the transfer. In detail, DI water was first added into the L-B trough; then, the oil phase was added at the top of the water phase. The system was settled for 20 min, and then the oil phase was washed out to remove residual polymers. Finally, the water phase was removed by a syringe pump, and the interfacial film was loaded onto the silicon wafer.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) for particle size measurement

DLS (Malvern Zetasizer ZEN 3600) was used to characterize the sizes of substrates. As discussed in the main text, PAN particles formed before assembly. Herein, DLS was used to characterize the size of PAN particles. The oil phase was directly used to carry out DLS measurements. To qualitatively investigate whether PAN particles were transferred from the oil phase to the water phase, we extracted the water phase before and after the interfacial assembly. When extracting the water phase, the oil phase was first removed by pipette, then a needle (gauge 0.5 mm) was used to extract the water phase out of the cuvette. Note that there might be some oil residual at the upper surface of the water phase. We only took part of the water phase to avoid mistakenly extracting the oil phase together with the water phase.

UV–Vis spectra for the measurement of diffusion speed of R6G

To demonstrate the function of temperature-responsive PNIPAM film as a switch to control the mass transfer across the oil-water interface, UV–Vis spectra (Lambda 2 UV–Vis Spectrometer) were used to quantify the adsorption strength of R6G and indicate the amount of R6G that diffuses across the oil-water interface.

Three control experiments were demonstrated:

Sample 1: oil phase was a mixture of MeOH and toluene ([MeOH]oil = 18.6 wt.%), with [PNIPAM]MeOH = 1 mg mL-1. PNIPAM was pre-assembled at the oil-water interface by CSAA.

Sample 2: oil phase was a mixture of MeOH and toluene ([MeOH]oil = 18.6 wt.%), with [PNIPAM]MeOH = 1 mg mL-1. PNIPAM was pre-assembled at the oil-water interface by CSAA.

Sample 3: oil phase was a mixture of MeOH and toluene ([MeOH]oil = 18.6 wt.%), without PNIPAM.

The ratio of the oil phase to the water phase was 1:2 (v/v). The system was maintained at 40 °C for 20 mins to allow the CSAA, followed by adding the R6G/MeOH solution ([R6G]MeOH = 0.3 wt.%) into the oil phase. To trigger the switch function of PNIPAM film, the temperature of sample 2 was then reduced to 0 °C while the others were kept at 40 °C. After settling for 20 min, the water phase was extracted for the UV–Vis characterization. The absorption intensity of the UV–Vis spectra indicated the amount of R6G that diffused across the oil-water interface.

Fabrication of photoelectric detector by CSAA

Polymers perylene diimides (PDI) derived polymer, PDI-N-DEN was used as an active layer to fabricate a photoelectric detector. The first step was to prepare PDI-N-DEN film by CSAA. In detail, PDI-N-DEN was dissolved in TFE to a concentration of 0.5 mg mL-1, followed by mixing with toluene to form the oil phase. Then the oil phase was mixed with water (1:3, v/v) in a homemade L-B trough. The system was settled for 2 h to allow CSAA to happen. Then PDI-N-DEN film could be obtained at the oil-water interface and subsequently loaded onto an interdigital electrode by L-B method. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 17, the interfacial film was loaded onto a substrate, such as a silicon wafer. After the interfacial assembly, the oil phase (yellow) was flushed to eliminate residual polymers. During this process, syringe pump 1 and syringe pump 2 were operated simultaneously: syringe pump 1 injected fresh oil (in the absence of the target polymer X) while syringe pump 2 withdrew the old oil phase (containing the target polymer X). The flow rates of the syringe pumps were carefully adjusted to be compatible and slow enough to avoid disturbing the interface. After refreshing the oil phase, syringe pumps 1 and 2 were stopped, and syringe pump 3 was activated to withdraw the water phase. This action lowered the interface and transferred the 2D polymer film to the substrate.

The commercially available interdigital electrode has a polyimide substrate with the dimension of 10 mm × 10 mm, and 15 pairs of fingers with a line width of 100 µm and a line gap of 50 µm. The structure of the electrode is Cu/Ni/Au with a thickness of 12 µm/3 µm/1 µm. The photoelectric response was measured by using periodic illumination (λ = 365 nm or 500 nm), and the duty cycling was 10 s. A KEITHLEY2400 source meter was used as both voltage input and photocurrent detector, and the bias voltages were 0.2 V, 0.5 V, and 1 V.

All-liquid 3D printing

A commercially available 3D printer (SnapMaker 2.0 A350) was used to print oil thread in the water phase. A stainless steel needle with 14 gauge (internal diameter = 1.60 mm) was used as printing nozzles to attach to the syringe pump. The printing figure was programmed by GCode. The programmed printing figure was spiral. The flow rate of the oil phase was set to 0.5 mL min−1, and the moving speed of the printing nozzle was 500 mm min−1. The printing phase was PAN-DMSO-DCM, in which [DMSO]oil and [PAN]DMSO were 24.86 wt.% and 8 mg mL-1, respectively. To delay the coalescence of the printed oil thread so that there was enough time for the interfacial assembly to finish and lock in the interface shape, the water phase’s viscosity was tuned by adding PEG (40 wt.%) to the water phase29.

Molecular dynamics simulations

All the molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed on GROMACS 2023 platform30, and trajectories were analyzed in VMD31 software. The OPLSAA force field32 was used to depict the L-J parameters of the molecules. The SPCE model was applied to depict water molecules. The parameters of DMSO and toluene were from LigParGen33,34,35. A cut-off of 12 Å was used to calculate the short-range electrostatic interactions and van der Waals (vdW) interactions. The long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method. The V-rescale thermostat and the Parrinello-Rahman barostat were applied to control the temperature at around 300 K and the pressure at 1 atm, respectively. The periodic boundary conditions (PBC) were applied in all directions. The timestep was set to 2 fs, and the trajectories were output every 1000 steps. The DMSO molecules were first solved in water and toluene, respectively, to form two different solutions. After equilibration, the boxes of the water and the oil solutions were merged to form the water-oil bi-phase system. The bi-phase system first minimized energy for 3000 steps, followed by equilibrations in NVT for 4 ns and in NPT for 6 ns, respectively. During the equilibration, the locations of DMSO molecules were fixed. The restraints were removed in the following 40-ns production simulation in the NVT ensemble. The last 10-ns trajectory was extracted to do data analysis, such as the calculation of the density of water, toluene, and DMSO molecules.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings in this work are freely available through Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12780083 (ref. 36).

Code availability

The code used for the 3D printing is freely available through Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12780083 (ref. 36).

References

Ringler, P. & Schulz, G. E. Self-assembly of proteins into designed networks. Science 302, 106–110 (2003).

Tsupko, P., Sagiri, S. S., Samateh, M., Satapathy, S. & John, G. Self-assembled trehalose amphiphiles as molecular gels: a unique formulation to wax-free cosmetics. J. Surfactants Deterg. 26, 369–385 (2023).

Liu, K. et al. On-water surface synthesis of crystalline, few-layer two-dimensional polymers assisted by surfactant monolayers. Nat. Chem. 11, 994–1000 (2019).

Shen, Q. et al. When self-assembly meets interfacial polymerization. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf6122 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. On-water surface synthesis of charged two-dimensional polymer single crystals via the irreversible Katritzky reaction. Nat. Synth. 1, 69–76 (2022).

Song, L. et al. Instant interfacial self-assembly for homogeneous nanoparticle monolayer enabled conformal “lift-on” thin film technology. Sci. Adv. 7, eabk2852 (2021).

Sasmal, H. S. et al. Covalent self-assembly in two dimensions: connecting covalent organic framework nanospheres into crystalline and porous thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20371–20379 (2019).

Shi, Y., Sánchez-Molina, I., Cao, C., Cook, T. R. & Stang, P. J. Synthesis and photophysical studies of self-assembled multicomponent supramolecular coordination prisms bearing porphyrin faces. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9390–9395 (2014).

LeMieux, M. C. et al. Self-sorted, aligned nanotube networks for thin-film transistors. Science 321, 101–104 (2008).

Zheng, J. et al. Directed self-assembly of herbal small molecules into sustained release hydrogels for treating neural inflammation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1604 (2019).

Vitale, S. A. & Katz, J. L. Liquid droplet dispersions formed by homogeneous liquid−liquid nucleation: “The Ouzo Effect”. Langmuir 19, 4105–4110 (2003).

Böker, A., He, J., Emrick, T. & Russell, T. P. Self-assembly of nanoparticles at interfaces. Soft Matter 3, 1231–1248 (2007).

Chevalier, Y. & Zemb, T. The structure of micelles and microemulsions. Rep. Prog. Phys. 53, 27 (1990).

Wennerström, H. & Lindman, B. Micelles. Physical chemistry of surfactant association. Phys. Rep. 52, 1–8 (1979).

Forth, J. et al. Building reconfigurable devices using complex liquid–fluid interfaces. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806370 (2019).

Wang, B. et al. The assembly and jamming of nanoparticle surfactants at liquid–liquid interfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202114936 (2022).

Chai, Y., Lukito, A., Jiang, Y., Ashby, P. D. & Russell, T. P. Fine-tuning nanoparticle packing at water–oil interfaces using ionic strength. Nano Lett. 17, 6453–6457 (2017).

Huang, C. et al. Structured liquids with pH-triggered reconfigurability. Adv. Mater. 28, 6612–6618 (2016).

Zhao, S. et al. Shape-reconfigurable ferrofluids. Nano Lett. 22, 5538–5543 (2022).

Del Monte, G. et al. Two-step deswelling in the volume phase transition of thermoresponsive microgels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2109560118 (2021).

Shim, J. et al. Two-minute assembly of pristine large-area graphene based films. Nano Lett. 14, 1388–1393 (2014).

Feng, W. et al. Harnessing liquid-in-liquid printing and micropatterned substrates to fabricate 3-dimensional all-liquid fluidic devices. Nat. Commun. 10, 1095 (2019).

Forth, J. et al. Reconfigurable printed liquids. Adv. Mater. 30, 1707603 (2018).

Liu, T., Yin, Y., Yang, Y., Russell, T. P. & Shi, S. Layer-by-layer engineered all-liquid microfluidic chips for enzyme immobilization. Adv. Mater. 34, 2105386 (2022).

Shi, S. et al. Liquid letters. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705800 (2018).

Li, M. et al. Structured liquids stabilized by polyethyleneimine surfactants. Soft Matter 19, 609–614 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Interfacial assembly and jamming of soft nanoparticle surfactants into colloidosomes and structured liquids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 54287–54292 (2022).

Ariga, K., Yamauchi, Y., Mori, T. & Hill, J. P. 25th anniversary article: what can be done with the langmuir-blodgett method? Recent developments and its critical role in materials science. Adv. Mater. 25, 6477–6512 (2013).

Xie, G. et al. Compartmentalized, all-aqueous flow-through-coordinated reaction systems. Chem 5, 2678–2690 (2019).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2, 19–2 (2015).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 27–38 (1996). 33-38.

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236 (1996).

Jorgensen, W. L. & Tirado-Rives, J. Potential energy functions for atomic-level simulations of water and organic and biomolecular systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 6665–6670 (2005).

Dodda, L. S., Cabeza de Vaca, I., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. LigParGen web server: an automatic OPLS-AA parameter generator for organic ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W331–W336 (2017).

Dodda, L. S., Vilseck, J. Z., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. 1.14*CM1A-LBCC: localized bond-charge corrected CM1A charges for condensed-phase. Simul. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 3864–3870 (2017).

Zhao, S. et al. Dataset for ‘Chaperone solvent assisted assembly of polymers at the interface of two immiscible liquids’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12780083 (2024).

Sulaman, M. et al. Hybrid nanocomposites of all-inorganic halide perovskites with polymers for high-performance field-effect-transistor-based photodetectors: an experimental and simulation study. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2200017 (2022).

Hung, C.-C., Chiang, Y.-C., Lin, Y.-C., Chiu, Y.-C. & Chen, W.-C. Conception of a smart artificial retina based on a dual-mode organic sensing inverter. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100742 (2021).

Song, I. et al. Surface doping effect on the optoelectronic properties of tetrachloro-substituted chiral perylene diimide supramolecular nanowires. Chem. Mater. 34, 8675–8683 (2022).

Pal, A., Gedda, M. & Goswami, D. K. PTCDI-Ph molecular layer stack-based highly crystalline microneedles as single-component efficient photodetector. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 4, 946–954 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Extended perylene diimide double-heterohelicenes as ambipolar organic semiconductors for broadband circularly polarized light detection. Nat. Commun. 12, 142 (2021).

Jung, J. H. et al. High-performance UV–Vis–NIR phototransistors based on single-crystalline organic semiconductor–gold hybrid nanomaterials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1604528 (2017).

Tarsoly, G., Park, S. & Pyo, S. In situ PTCDI-aided lateral crystallization of benzothieno-benzothiophene derivative for photoresponsive organic ambipolar devices. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 11465–11472 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (Project No.21304421, Y.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 22003053, Y.C.), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Project No. 2023A1515011457, Y.C.), the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province, China (Project No. 2023NSFSC0312, Y.C.), CityU Strategic Interdisciplinary Research Grant (Project No. 2020SIRG035, Y.C.), and Hong Kong Institute for Advanced Study. The authors also thank OpenAI for editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. supervised the project. S.Z., Y.L., X.C.Z., and Y.C. designed the project. S.Z. and Y.C. conducted the interfacial experiments and analyzed the data. S.Z., C.H., and X.C.Z. conducted the MD simulations. S.Z., Y.F., Q.Z., and L.H. carried out the interfacial tension measurement and contributed to the data analysis. Y.J. and Y.L. synthesized the PDI-derived polymers. S.Z., Y.J., Y.L., and Y.C. fabricated the photoelectric detectors and conducted performance tests. S.Z. and W.C. analyzed the interfacial viscoelasticity. S.Z. and Y.C. wrote the manuscript with input from all coauthors. All authors were involved in data interpretation and discussion.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, S., Jiang, Y., Fu, Y. et al. Chaperone solvent-assisted assembly of polymers at the interface of two immiscible liquids. Nat Commun 15, 7423 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51657-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51657-3