Abstract

Biomimetic robots yearn for compliant actuators that are comparable to biological muscle in both functions and structural properties. For that, electrostatic actuators have been developed to imitate bio-muscle in features of fast response, high power, energy-efficiency, etc. However, those actuators typically lack impact damping performance, making them vulnerable and unstable in real applications. Here, we present auxetic electrostatic actuators that address this issue and demonstrate muscle-like performance by using elastomer-enhanced auxetics and electrostatic zipping mechanism. The proposed actuators contract linearly on applied voltage, producing large actuation strength (15 N) and contraction ratio (59%). Fabricated from readily available materials, our prototypes can quickly attenuate vibrations caused by impacts and absorb shock energy in 0.3 s. Furthermore, leveraging their 2-dimensional working mode and self-locking mechanism, a stiffness-changing muscle for a robotic arm and an active tensegrity device exemplify the potential applications of auxetic electrostatic actuators to a wide range of bionic robots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To replicate the behavioral diversity of creatures in nature, bionic robots need intelligent design of compliant actuators that can work efficiently and interact safely with dynamic environment1,2,3,4,5. The human muscle is an ideal example of such actuator, which not only exhibits remarkable functions of actuation, but also possesses superior structural properties such as impact damping, varying stiffness, and structural stability6,7. For long time the electrostatic actuators8,9,10,11,12 have been pursuing better performance in actuation. However, they tend to be mechanically vulnerable to impacts and difficult to attenuate vibrations, making them impractical in unstructured and unpredictable environments. This highlights the need for impact-damping electrostatic actuators that can quickly recover from impacts without causing large and persistent fluctuations.

Current soft actuators are mainly driven by fluid13,14, thermal stimulation15, and electrical power16. Among them, electrically powered actuators have many merits, involving fast response, energy efficiency, self-sensing, simple setup, etc. Many related researches are devoted to dielectric elastomer (DE) actuators17,18,19, which are usually miniaturized in actuation force and stroke. Besides, DE actuators usually need prestretch to perform effectively. Recently, some electrostatic actuators have been developed by using liquid-amplified electrostatic force to achieve high performance and versatility. HASEL actuators8,9 revealed the potential of this concept in building large scale artificial muscle. Then electro-ribbon actuators10,11 incorporated liquid-amplified electrostatic force with electrostatic zipping, while removing excess liquid dielectric and encapsulation of HASEL actuators. Such modifications enable electro-ribbon to form various origami structures with different shapes and functions. Using similar working principle to HASEL and electro-ribbon, electrostatic bellow muscle12 (EBM) integrated multiple functions, involving actuating, pumping, and energy harvesting, in a single lightweight device. Unfortunately, these actuators were only tested in aspects of strength, stroke, power density, etc., while their structural properties were ignored in the tests. In fact, when pursuing high performance metrics of actuation, structural stability and impact damping were often sacrificed in electrostatic actuators, making their structural properties quite different from bio-muscle. Due to that, it is essential to integrate electrostatic actuators with structures that are impact damping during operations20.

Here, we present a class of auxetic electrostatic actuators (AELAs) that can be easily fabricated from daily found materials. By integrating the principles of auxetics21,22,23, we can improve resilience to damage and disturbances24,25,26,27,28,29,30, allowing the AELAs to outperform the state of the art in several ways: i) The auxetic structure of AELA is constrained by elastic tensile network, so it can withstand heavy loads and deform uniformly in operation, although the auxetic structure itself is flexible and can easily go through structural failure; ii) it can achieve reversible large deformation through the buckling and zipping of beam elements of auxetics, producing large actuation strength and stroke; iii) AELA can absorb and dissipate shock energy quickly with its elastomer enhanced auxetic configuration; iv) it has the feature of operating in 2 dimensions, which provides more freedom when arranging multiple actuators.

Results

Design and working principle

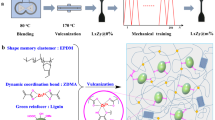

AELAs operate on electrostatic zipping of elastomer-enhanced auxetics. As shown in Fig. 1a, the actuator consists of an auxetic structure and elastomers. The buckled parts of the auxetic structure serve as beams to withstand compressive force, while the elastomers act as tendons to convey tension. The structure of AELA can be mathematically modelled by a graph of network of beams and tendons31,32 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The detailed mathematical model and analysis (Supplementary Figs. 2 to 7) are provided in Supplementary Methods. The fabrication of standard and lightweight AELAs is depicted in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 8.

a Diagram of AELA, where components are distinguished by different colors. b Steps to fabricate AELA from a prepared origami sheet. c Force diagram of AELA. \({F}_{n}\) and \({F}_{N}\) are internal forces, while \({F}_{x}\) and \({F}_{y}\) are external forces. d Photographs of standard AELA, operating in longitudinal mode. e AELA operating in lateral mode. f Enlarged schematic of a hinge at three different applied voltages. \(V\) and \({V}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) are applied voltage and critical voltage, respectively. Initially, the hinge is open under external force and the electro-beam is buckled. At an intermediate voltage, the hinge tends to close, but electrostatic force is not large enough to compensate external force. At a voltage higher than critical voltage, the hinge fully closes. Scale bars, 1 cm.

The proposed design enables AELAs to safely support and lift heavy loads, as well as withstand impacts. Subjected to external loading, the actuator expands on both longitudinal and lateral directions. During expansion, the elastomers are stretched, while the beam elements of auxetic structure are buckled (Fig. 1c). The elastomer-enhanced auxetic topology enables the actuator to efficiently absorb external mechanical energy in buckled beams and stretched elastomers. The reserved energy can be further released to assist actuation. Moreover, this design enables different hinges of the actuator zip synergistically, which cannot be realized by the auxetic structure per se.

Unlike other soft actuators that usually operate in one dimension, AELAs can operate in both longitudinal and lateral dimensions (Fig. 1d and e), leading to 2 distinct operation modes that provide different ranges of strength, stroke, and load capacity.

The actuator contracts when high voltage is applied to the electrodes, creating strong electric field at the hinges (Fig. 1f). Silicone oil (Xiameter PMX 200, 5 cSt) is added at the hinges to enhance the electrostatic force10. The electrostatic force induces strain that counteracts the compression of the buckled beams. This process is featured by pull-in transition33,34. For voltage lower than critical value, the beams are kept bent. When applied voltage exceeds critical value, the beams zip along opposite electrodes, causing the actuator to contract (Fig. 1f).

Characterization

Auxetic structure with flexible hinges is vulnerable to heavy loads during deformation. However, the addition of elastomer tensile network can significantly improve the structural strength of auxetic structure, while retaining its flexibility. The load-carrying capacity of a single AELA was investigated in quasi-static loading and unloading tests (Supplementary Fig. 9) without applying voltage. In each test, the actuator extension was changed monotonically in a quasi-static process. The results in Fig. 2a show that the AELA can safely withstand loads over 10 N longitudinally and 3 N laterally, without structural failure or excessive deformation. In addition, hysteresis loop was observed in the passive force-extension curves, indicating that the actuator passively dissipated mechanical energy even when it deformed very slowly. The passive force showed significant nonlinearity to the extension in the longitudinal direction. Specifically, the actuator had much higher stiffness at small extensions than at large extensions, implying stiffness softening. This feature enables the actuator to effectively resist small disturbances while be compliant to large external force.

a Hysteresis loops of passive force-extension curves obtained in quasi-static loading and unloading tests. The arrows denote the loading directions. b Actuation of AELA in longitudinal and lateral modes under loads of 900 g and 200 g, respectively. c Varying contractile forces of AELA at applied voltages of 4 kV, 6 kV, and 8 kV in quasi-static unloading tests. d Strain-voltage curves of AELA under different loads. e Actuation of customized AELA in longitudinal and lateral modes under loads of 1500 g and 150 g, respectively. f Responses of current, voltage, and displacement during actuation of AELA. Scale bars, 1 cm.

In longitudinal actuation mode, a standard prototype of AELA can fully lift loads over 900 g at an applied voltage of 9 kV, with a contraction of 4.2% the initial length (Fig. 2b). In lateral actuation mode, the load that a single AELA can fully lift at the same voltage is 200 g, with a contraction ratio of 55%. The corresponding energy densities are 0.78 J kg−1 (1.88 J kg−1 per active core mass) in longitudinal mode and 0.55 J kg−1 (1.32 J kg−1 per active core mass) in lateral mode. At different applied voltages, the contractile forces of AELA during contracting processes were measured in quasi-static unloading tests. At the beginning of the unloading tests, the contractile forces decreased slowly due to the decline of dominant structural tensions, but then increased rapidly at small extensions due to electrostatic force (Fig. 2c). The minimum longitudinal contractile forces at applied voltages of 4 kV, 6 kV, and 8 kV were 6 N, 7.5 N, and 8.5 N, respectively. The minimum lateral contractile forces at the same voltages were 0.9 N, 1.6 N, and 2 N, respectively. Electrostatic force became very large when the actuator fully contracted, resulting in self-locking forces that were much higher than normal working load. At 8 kV, the experimentally measured self-locking forces were 115 N longitudinally and 36 N laterally (Supplementary Fig. 10). The contraction ratios for different weights at varying applied voltage are shown in Fig. 2d. The pull-in voltages, at which the actuator fully contracted, are recorded in Supplementary Fig. 11.

The simple working principle of AELAs allows diverse selections of materials for fabrication. The performance of the actuator can be tuned by using different materials. Generally, a higher stiffness of elastomer enhances the structural stability, the load capacity, and the contractile force of the actuator, but reduces the strain, while a lower stiffness has the opposite effect. The bending stiffness of beam in the auxetic structure affects the maximum load capacity and contractile force. With higher bending stiffness, the beam can resist higher external loads and generate higher contractile force. Besides, the stiffness of either the elastomer or the beam affects the response speed and thus the power of the actuator. As shown in Fig. 2e and Supplementary Movie 1, by increasing the stiffness of elastomer, the actuator can fully lift loads of 1500 g in the longitudinal direction. By reducing the stiffness of elastomer, the actuator can achieve a lateral contraction ratio of 59%.

Figure 2f shows displacement, current, and voltage responses of a standard AELA under actuation. A current spike was observed at the onset of actuation, followed by a decrease to about 3 μA when the applied voltage reached 8 kV, indicating the completion of initial charging.

We tested the bandwidth of lightweight AELA (Supplementary Fig. 12, Supplementary Movie 2) and demonstrated the results in Fig. 3 (a and b). At a low frequency of 0.1 Hz during cyclic actuation, the actuator achieved longitudinal and lateral strokes of 1.5 mm and 5 mm, respectively. The stroke amplitude decreased as the frequency of the applied square wave voltage increased. Local extrema of stroke amplitude were observed at resonance frequencies. In the longitudinal direction, the resonance occurred at 8 Hz, with a stroke amplitude of 0.9 mm. In the lateral direction, the resonance occurred at 10 Hz, with a stroke amplitude of 2 mm.

a Time series of actuator displacement at different frequencies of applied voltage with longitudinal load of 200 g and lateral load of 100 g. b Amplitudes of actuator oscillation for different frequencies of applied voltage. c Measurements of displacement and specific power of AELA in longitudinal and lateral modes. d Cyclic testing over 60 thousand cycles.

As shown in Fig. 3c, the peak specific power was measured as 4.6 W kg−1 (9.1 W kg−1 per active core mass) and 3.1 W kg−1 (6.2 W kg−1 per active core mass) in the lateral and longitudinal directions, respectively. By increasing the elastic modulus of elastomer, the expansion of AELA was constrained in a small range, where the electrostatic force was maintained strong. This improved the specific power significantly. Under a lateral load of 700 g, the measured specific power reached 19.9 W kg−1 (29.1 W kg−1 per active core mass) at 7 Hz (Supplementary Fig. 13, Supplementary Movie 3).

In the test of isometric cyclic actuation (Fig. 3d), the actuator was mounted longitudinally with 3 mm elongation. Actuated by square wave voltage ranging from 0 kV to 6 kV, the actuator operated stably for 60,000 cycles at a frequency of 10 Hz, without deterioration of tensile force.

Demonstration of impact damping

When operated in two different dimensions, AELA demonstrates distinct load capacities and force-strain characteristics (Fig. 2). In longitudinal dimension, the actuator has large strength and relatively small stroke, while in lateral dimension, the actuator has relatively small strength and large stroke. For that, the comparisons between AELA and other soft actuators are divided into two groups (Figs. 4 and 5). In one group, AELA operates in longitudinal dimension, while in the other group, it operates in lateral dimension. The soft actuators for comparison include a Peano-Hasel actuator and a buckling pneumatic linear actuator named VAMP35 (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). Along with the soft actuators, we also tested a commercial shock absorber that was designed to work in the tested condition.

In longitudinal mode testing, a piece of iron weighting 200 g was released from a height of 3.5 cm above a 500 g iron plate hanging to the actuator, causing impulses of approximately 3.1 N⋅s. Tests showed that impact was quickly damped down by the actuator in around 0.23 s, with the peak displacement of 1.4 mm and the peak tension force of 18.7 N (Fig. 5a). In contrast, the VAMP caused persistent oscillation that lasted around 4.4 s and had a large amplitude around 7.5 mm. The Peano-Hasel oscillated for around 1.5 s, with the peak displacement over 3.3 mm. The commercial shock absorber outperformed the VAMP and the Peano-Hasel in stabilization time (0.5 s) and peak displacement (2.1 mm), while its peak tension force reached 26.4 N.

In lateral mode testing, the weights of dropping iron and iron plate were reduced to 50 g and 100 g, respectively, because the actuator had a lower carrying capacity in this mode than in the longitudinal mode. The impulses from the collisions were around 0.28 N⋅s. The actuator oscillated for around 0.23 s after impact, with the peak tension force of 2.9 N and the peak displacement of 3.3 mm (Fig. 5a). In comparison, the VAMP and the Peano-Hasel oscillated for 1.5 s and 0.6 s, respectively. Besides, the peak tension force generated by the Peano-Hasel is 7.9 N. The commercial shock absorber damped down quickly in 0.18 s, but had a peak tension force of about 9.4 N.

Overall, the AELA damped down much faster than the VAMP and the Peano-Hasel in both longitudinal and lateral mode testing. Particularly in longitudinal mode, the AELA was even better than the commercial shock absorber in impact damping. A straightforward comparison of the impact damping performances is given in Fig. 5b.

Arrays of actuators

The AELAs can be scaled up by connecting multiple actuators longitudinally and laterally to achieve higher contractile force and larger stroke (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Movie 4). The fabrication process of the scaled-up actuators is similar to that of a single actuator. Scaled-up arrays preserve the 2-dimensional working mode of a single actuator. Theoretically, for an array with n longitudinally connected actuators multiplied by m laterally connected actuators, the longitudinal stroke and working load should be magnified by n times and m times respectively. For the same array, the lateral stroke and working load should be magnified by m times and n times respectively. Figure 6a to c shows a 3 × 1 array and a 1 × 3 array that worked at an applied voltage of 9 kV. For the 3 × 1 array, the longitudinal stroke increased to 8.8 mm, while the lateral working load increased to 600 g. For the 1 × 3 array, the lateral stroke was amplified to around 21 mm, while the longitudinal working load was amplified to 2700 g. The discrepancies between the theoretical predictions and the experimental results are mainly due to the self-weight of actuators and the attachment of end effectors.

a Comparison of the stroke-force performances of 1 AELA, 3 × 1 array, and 1 × 3 array at 9-kV applied voltage. Dashed lines represent theoretically scaled performances with respect to 1 AELA. b In longitudinal direction, a 3 × 1 array (left) and a 1 × 3 array (right) produce strokes of 8.8 mm and 2.4 mm against loads of 900 g and 2700 g, respectively. c In lateral direction, a 1 × 3 array (left) and a 3 × 1 array (right) produce strokes of 21.2 mm and 7.5 mm against loads of 200 g and 600 g, respectively. Scale bars, 2 cm.

The AELAs can be arranged flexibly to adapt to different working conditions. A robotic arm was built to illustrate that. Three sets of experiments were conducted using the actuators to drive a 3D printed arm with 1:5 load-to-effort ratio (Supplementary Fig. 16). First, a 1 × 3 array was built to verify the ability of large stroke (Fig. 7a). With a load of 15 g, the robotic arm could generate a displacement of 155 mm. Then, a customized 1 × 3 array was built to demonstrate the ability of large output force (Fig. 7b). At a voltage of 8 kV, the actuators could lift 500 g weights hanged at the end of the arm, corresponding to 25 N effort force. After that, two actuators were assembled in a mixed manner to show the ability of working mode transition. In this set of experiments, the top actuator was placed longitudinally, and the bottom actuator was placed laterally. Utilizing the self-locking mechanism, which enables AELA to keep fully contracted at a relatively low voltage even when the imposed load is much higher than its maximum working load, the mixed array could switch between high force mode and large stroke mode during operation. When the applied voltage was set as 8 kV, the laterally placed actuator can fully contract and lift a 15-g load, producing a stroke of 40 mm at the end effector. Then the load was increased to 100 g while the applied voltage was maintained 8 kV. Though the load leads to a visible deformation of the 3D printed forearm, the lateral actuator kept closed and contracted (Fig. 7c). On this occasion, the actuators can switch from the large stroke mode to the high force mode. Then the longitudinally placed actuator was activated to drive the robotic arm. As shown in Fig. 7c, the load was further lifted by a displacement of 8 mm. This experiment demonstrated the possibility of using the AELAs for complicated manipulation with mode transition.

a A 1 × 3 array working in its lateral direction lifts a load of 15 g for 155 mm. b A customized 1 × 3 array working in its longitudinal direction lifts 500 g for 15 mm. c A mixed array shows transition of working mode from large stroke to large force, with the aid of self-locking. Scale bars, 3 cm.

Application to an active tensegrity

AELA can act as artificial muscle that allows active contraction, impact damping, and self-locking. For demonstration, we built an active tensegrity that looks like a “floating table” (Fig. 8a). It is composed of isolated compressive struts, i.e., 3D printed frames, and stretched flexible elements, i.e., rubber bands and AELAs. In this active tensegrity, the two rigid frames were connected to each other with rubber bands and AELAs as shown in Supplementary Fig. 17. The peripheral actuators were mounted laterally, while the central actuator was mounted longitudinally.

a Diagram of the designed tensegrity, where compressive struts and flexible elements are 3D-printed rigid frames and AELAs, respectively. b A 1 × 3 array produces 10° bending of the tensegrity. c A self-locking AELA prevents bending of the tensegrity under external load. d A self-locking AELA prevents the tensegrity against compression under heavy load. e Collision test of the tensegrity. Scale bars, 2 cm.

In bending tests, 3 AELAs were mounted laterally in series at a peripheral position of the active tensegrity. At an applied voltage of 8 kV, the actuators fully contracted, leading to obvious bending of the tensegrity (Fig. 8b). The measured bending angle was 10°. Further, the same actuators can prevent unwanted bending of the tensegrity by self-locking. As Fig. 8c shows, the bending angle induced by external weights decreased from 20° to 2° with a single AELA. The active stiffness changing via self-locking was further demonstrated by mounting an AELA longitudinally at the central position of the tensegrity. Without applied voltage, the actuator passively expanded under a weight of 500 g, leading to compression of the tensegrity (Fig. 8d, left). However, when the actuator was applied with a high voltage that enabled it to fully contract, the tensegrity could withstand 1000 g weights without being compressed (Fig. 8d, right). At last, we tested the impact-resistance of the tensegrity. A weight of 200 g was released at 20 cm above the impact position (Fig. 8e). Slow motion (Supplementary Movie 5) shows that the actuator expanded obviously at the instance of impact to absorb impact energy and stabilized the tensegrity.

Discussion

The presented auxetic electrostatic actuator is a combination of electrostatic actuator and auxetic structure for building actuating bionic robots. The actuator can be easily fabricated, with elastic tendons added to strengthen and stabilize the auxetic structure. For that, AELA can withstand heavy loads and effectively resist impacts. Upon actuation, the actuator contracts in both the longitudinal and the lateral directions, enabling 2-dimensional operation that is seldom presented in other electrostatic actuators. Multiple AELAs can be assembled flexibly into arrays, where the stroke and the contractile force scale up linearly. Moreover, mixed arrays of the actuators allow mode transition during operation.

The overall actuation performance of AELA is comparable to its state-of-the-art counterparts, with particularly large force in the longitudinal direction and high strain in the lateral direction. In addition, AELA is easy to scale up without compromising its structural integrity. Under impact, the actuator damps down oscillations quickly and outperforms commercial shock absorber, making it distinct from its counterparts. The fabrication of AELA is versatile and low cost. It can be made lighter and more powerful with coating electrodes and dielectrics that have higher permittivity and breakdown strength. Our tests were conducted under 10 kV. However, by utilizing dielectric materials with higher breakdown strength or self-healing properties, we can apply higher voltage to further improve the performances. In summary, AELA simultaneously takes care of structural requirements and actuation properties of biomimetic actuators, highlighting its potential in designing compliant bionic robots.

Methods

Fabrication

The fabrication processes of standard and lightweight AELAs involves 3 steps.

Preparing auxetic structure

For standard AELA, the auxetic structure is made from two multilayer sheets, each of which has 7 layers. From the outermost layers to the central layer, the materials are dielectric (PVC), electrode (copper), adhesive tape, and insulator (PET). First, the copper foils are attached to the two sides of PET film using adhesive tape. Then a cutting machine (CAMEO 4, Silhouette) is used to cut out the shape of copper electrodes, without cutting through the adhesive tape and PET film. After peeling off excess copper around the electrodes, PVC films are attached upon the electrodes to complete the multilayer sheet.

For lightweight AELA, the sheet has only 3 layers, i.e., two layers of PVC film and a layer of electrodes. The electrode layer is cut by cutting machine first, and then fixed on a PVC film to remove excessive copper. After that, another PVC film is attached to the electrode layer. The PVC films are pressed together by a heat press machine to seal the electrodes.

Further, V-grooves are cut out on the multilayer sheet to facilitate the anchoring of rubber bands. Deep U-shaped grooves are cut out at the two ends of the sheet to anchor the elastomer shell. The positions of the grooves are marked out in Supplementary Fig. 8. Then the sheet is folded into the designed shape. To make the hinges of the folded sheet tightly closed, the hinges are wrapped with 5-mm-wide PVC band, while the heat-press is set to 100 °C and pressed on the hinges for 15 s to make the opposite PVC layers of each hinge bonding together. As an option, the folded sheet can be strengthened by adding load-bearing rigid plates as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. By symmetrically bonding two folded sheets, the auxetic structure is completed.

Preparing the elastomer shell

Part A and part B of Ecoflex 00-30 is fully mixed in ratio of 1:1. Then the mixture is put in a vacuum drying oven to get rid of air bubbles. After that, the mixture is poured into a 3D printed mold and put back to the vacuum drying oven to cure for 5 mins. The solidification takes around 4 hours at room temperature. The design of the mold is shown in Supplementary Fig. 18. The geometry of the mold can be customized to adjust the pre-stress of the elastomer shell. In lightweight AELA, the elastomer shell can be replaced by rubber bands.

Completion of AELA

The elastomer shell and rubber bands are anchored on the auxetic structure via V-grooves and U-grooves, respectively. Before tests, silicone oil (Xiameter PMX 200, 5 cSt) is added to the hinges.

Tensile testing

The contractile force of AELA varies with the extension and the applied voltage. To investigate the contractile force-extension characteristics, we performed the loading and unloading tests of the actuator on a tensile strength tester with an accurate force gauge (IMADA ZTS-20N). The high voltage was provided by a voltage amplifier (Q101-5, EMCO).

Passive force

The passive forces of AELA were obtained without applied voltage. Before each loading test, the tester was reset to the position where the actuator was fully contracted. Then the actuator was stretched uniformly and slowly to the prescribed extension. After that, the actuator was recovered slowly from the prescribed extension to the fully contracted state. Both loading and unloading tests were conducted quasi-statically to capture the passive tensile force.

Contractile force

The contractile forces of AELA were obtained in quasi-static unloading tests at different applied voltages. Before each unloading test, the actuator was stretched to the prescribed extension and applied with high voltage. Then the actuator was kept at the same extension until the initial measurements of contractile force settled down. After that, the actuator was recovered quasi-statically to the fully contracted state.

Self-locking force

To measure the self-locking force of AELA, we let the actuator fully contract under applied voltage and then performed quasi-static loading using the tensile tester until the actuator was pulled apart. Due to that the self-locking force was out of the measurement range of IMADA force gauge, we used CELTRON weighting sensor (STC-100kg) instead. The recorded highest loading force was taken as the self-locking force in each test.

Isotonic testing

The isotonic testing was conducted to measure the pull-in voltages and strokes. Constant mass was mounted at the lower end of AELA. The applied voltage was increased stepwise by 1 kV each time until the actuator fully contracted. In each test, the lowest voltage that caused full contraction was taken as the corresponding pull-in voltage. The strokes were obtained via laser displacement meter (optoNCDT 1420, MICRO-EPSILON).

Changing stiffness of AELA

The stiffness of AELA changes with the rubber bands fastened to the auxetic structure. In Fig. 2b, the standard AELA involved 1 pair of rubber bands. To increase the stiffness of the actuator, we added 1 more pair of rubber bands that are the same type of the original ones. At an applied voltage of 9 kV, the actuator can fully lift a longitudinal load of 1500 g. To decrease the actuator stiffness, we used a different type of rubber bands that have 10-mm diameter, 1-mm width, and 0.5-mm thickness to replace the original bands. At applied voltage of 9 kV, the lateral stroke was improved from 9.8 mm to 11.7 mm.

Measurements of voltage and current

To measure the voltage and current applied to AELA, we used an ultra-miniature high voltage converter (Q101-5, EMCO) as power source. It generated monitor voltage and current signals that corresponded to applied high voltage and current. The digital signals were recorded with a data acquisition device (USB-6363).

Bandwidth testing

The bandwidth testing was performed on lightweight AELAs. Without using PET insulator and double-sided adhesive tape in the origami, the actuators are more responsive to swift change of electric field strength. The setup of bandwidth testing was the same as that of isotonic testing. A data acquisition device (USB-6363) was used to generate the control signal of square wave voltage with an upper end of 9 kV and a lower end of −1 kV. The high voltage amplifier (HCAM 10-40, Huace) outputted high voltage according to the control signal. In the tests, the weights hanged on the actuator were 200 g and 100 g in longitudinal and lateral modes, respectively. The power of AELA in bandwidth testing was obtained by multiplying the loading force with the moving velocity of weights, which is numerically approximated from the measured displacements using the 7-th order polynomial fitting function polyfit (t, S, 7) in MATLAB.

Isometric cyclic actuation

Before the isometric cyclic actuation, the tested AELA was stretched by the tensile tester to a prescribed large extension and then slowly recovered to an extension of 3 mm. This was to avoid the bias caused by viscoelasticity of the actuator. We used a data acquisition device (USB-6363) to control a high voltage amplifier (HCAM 10-40) to output 10-Hz square wave voltage (0 kV to 6 kV). The frequency of the amplifier is as high as 100 Hz without distorting the shape of square wave voltage. During the cyclic actuation, the tensile force was recorded by a precise force gauge (IMADA ZTS-20N).

Impact damping tests

The experimental setup for impact damping tests is shown in Supplementary Fig. 14. The force gauge (IMADA ZTS-20N or 50 N) was fixed on a rigid frame, with its sensor connected with a test specimen, i.e., VAMP, AELA, Peano-Hasel, or commercial damper. The tested VAMP and Peano-Hasel had comparable size of AELA. The commercial shock absorber was an oil damper (RBC0604) with a length of 41 mm. The laser meter (MICRO-EPSILON optoNCDT 1420) was used to measure the displacements of the test specimens during impact. The mounting direction of commercial damper was opposite to the other specimens. The stabilization time is the time needed for the force fluctuations to decay within a certain range (±0.1 N for longitudinal mode testing, ±0.05 N for lateral mode testing) after impact. The data values in radar map (Fig. 5b) are rescaled with the maximum values. For example, \({T}_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}=T/{T}_{\max }\), where \(T\) is stabilization time, \({T}_{\max }\) is the maximum stabilization time of the tested actuators and shock absorber, \({T}_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}\) is rescaled stabilization time.

Arrays of AELAs

There are two approaches to build arrays:

-

(1)

AELAs are arranged into arrays using 3D printed connectors.

-

(2)

The array of auxetic structures is built first. Then rubber bands and elastomer shell are fixed on the array to complete it.

The first approach is convenient to build arrays of various forms such as those in Fig. 7 (a to c). However, the arrays built in the second approach actuate more synergistically as shown in Fig. 6 (b and c), because all actuators share the same elastomer shell that distributes tension force evenly to each actuator.

Tests of robotic arm

The robotic arm was printed by 3D printer (Z400D, HORI) using 1.75-mm PLA filament. The forearm weighted 70 g and had a length of 250 mm. On the forearm, there were uniformly distributed hangers for adjustment of position of weights (Supplementary Fig. 16). The effort-to-load force ratio of the robotic arm can be adjusted from 1 to 5. The moving end of AELA array was anchored to the hanger closest to the shaft using plastic cable ties.

There are two types of 1 × 3 arrays in Fig. 7 (a and b). The first type of array consisted of 3 actuators that were connected laterally and in series. In the other type, the actuators were parallelly connected using connectors shown in Supplementary Fig. 16. In the demonstration of mode switching (Fig. 7c), 2 actuators were connected in a mixed manner, i.e., one in longitudinal direction and the other in lateral direction.

Contraction of AELA can be controlled by input voltage. With applied voltage on, the actuator contracts until its contractile force and the loading force meet balance. Obviously, higher voltage causes more contraction. Once applied voltage exceeds pull-in voltage, the actuator will fully contract.

Tests of active tensegrity

The active tensegrity consisted of two oppositely placed frames that were interlocking and mutually connected by AELAs and rubber bands. Due to the balance of tension forces of the actuators and the rubber bands, the two rigid frames of the tensegrity have no contact with each other. The rigid components of the frames were printed by 3D printer (Z400D, HORI) using 1.75-mm PLA filament. Supplementary Fig. 17 demonstrates the assembly of the tensegrity and the geometry of the frames.

An array of 1 × 3 actuators was used to demonstrate the active bending of the tensegrity. In the demonstration of impact-resistance, an AELA was mounted longitudinally at the center of the tensegrity to absorb shock energy. The dropping weight was held using electromagnet and released at 20 cm above the impact position.

Data availability

All relevant data from this study are included in the paper and Supplementary Information. The experimental data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25845865). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code that supports this study is available as Supplementary Software or in Code Ocean (https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.9240742.v1). Further description of the code can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

References

Pfeifer, R., Lungarella, M. & Iida, F. The challenges ahead for bio-inspired ‘soft’ robotics. Commun. ACM 55, 76–87 (2012).

Laschi, C., Mazzolai, B. & Cianchetti, M. Soft robotics: Technologies and systems pushing the boundaries of robot abilities. Sci. Robot. 1, eaah3690 (2016).

Calisti, M., Picardi, G. & Laschi, C. Fundamentals of soft robot locomotion. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20170101 (2017).

Rus, D. & Tolley, M. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 521, 467–475 (2015).

Siviy, C. et al. Opportunities and challenges in the development of exoskeletons for locomotor assistance. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 456–472 (2023).

Gatt, R. et al. Negative Poisson’s ratios in tendons: an unexpected mechanical response. Acta Biomater. 24, 201–208 (2015).

Zhang, X., Chan, F. K., Parthasarathy, T. & Gazzola, M. Modeling and simulation of complex dynamic musculoskeletal architectures. Nat. Commun. 10, 4825 (2019).

Kellaris, N., Venkata, V. G., Smith, G. M., Mitchell, S. K. & Keplinger, C. Peano-HASEL actuators: Muscle-mimetic, electrohydraulic transducers that linearly contract on activation. Sci. Robot. 3, eaar3276 (2018).

Acome, E. et al. Hydraulically amplified self-healing electrostatic actuators with muscle-like performance. Science 359, 61–65 (2018).

Taghavi, M., Helps, T. & Rossiter, J. Electro-ribbon actuators and electro-origami robots. Sci. Robot. 3, eaau9795 (2018).

Diteesawat, R. S., Helps, T., Taghavi, M. & Rossiter, J. Electro-pneumatic pumps for soft robotics. Sci. Robot. 6, eabc3721 (2021).

Sîrbu, I. D. et al. Electrostatic bellow muscle actuators and energy harvesters that stack up. Sci. Robot. 6, eaaz5796 (2021).

Li, S., Vogt, D. M., Rus, D. & Wood, R. J. Fluid-driven origami-inspired artificial muscles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 13132–13137 (2017).

Wehner, M. et al. An integrated design and fabrication strategy for entirely soft, autonomous robots. Nature 536, 451–455 (2016).

Kanik, M. et al. Strain-programmable fiber-based artificial muscle. Science 365, 145–150 (2019).

Mirvakili, S. M. & Hunter, I. W. Artificial muscles: Mechanisms, applications, and challenges. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704407 (2018).

Tang, C. et al. A pipeline inspection robot for navigating tubular environments in the sub-centimeter scale. Sci. Robot. 7, eabm8597 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. A processable, high-performance dielectric elastomer and multilayering process. Science 377, 228–232 (2022).

Rosset, S. et al. Self-sensing dielectric elastomer actuators in closed-loop operation. Smart Mater. Struct. 22, 104018 (2013).

Hawkes, E. W., Majidi, C. & Tolley, M. T. Hard questions for soft robotics. Sci. Robot. 6, eabg6049 (2021).

Ren, X., Das, R., Tran, P., Ngo, T. D. & Xie, Y. M. Auxetic metamaterials and structures: a review. Smart Mater. Struct. 27, 023001 (2018).

Dagdelen, J., Montoya, J., Jong, M. & Persson, K. Computational prediction of new auxetic materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 323 (2017).

Papadopoulou, A., Laucks, J. & Tibbits, S. Auxetic materials in design and architecture. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17078 (2017).

Galuwaerts, K. et al. Design and control of compliant tensegrity robots through simulation and hardware validation. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140520 (2014).

Ingber, D. E., Wang, N. & Stamenović, D. Tensegrity, cellular biophysics, and the mechanics of living systems. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 046603 (2014).

Shah, D. S. et al. Tensegrity robotics. Soft Robot. https://doi.org/10.1089/soro.2020.0170 (2021).

Fung, Y. C. Skeletal Muscle in Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues (Springer, New York, 1993).

Wang, N. et al. Mechanical behavior in living cells consistent with the tensegrity model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7765–7770 (2001).

Levin, S. M. The tensegrity-truss as a model for spine mechanics: Biotensegrity. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2, 375–388 (2002).

Lee, H. et al. 3D-printed programmable tensegrity for soft robotics. Sci. Robot. 5, eaay9024 (2020).

Schek, H. J. The force density method for form finding and computation of general networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 3, 115–134 (1974).

Levien, R. The elastica: a mathematical history. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.226.2020&rep=rep1&type=pdf (2008).

Budiansky, B. Theory of buckling and post-buckling behavior of elastic structures. Adv. Appl. Mech. 14, 1–65 (1974).

Overvelde, J. T. B., Kloek, T., D’haen, J. J. A. & Bertoldi, K. Amplifying the response of soft actuators by harnessing snap-through instabilities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10863–10868 (2015).

Yang, D. et al. Buckling Pneumatic Linear Actuators Inspired by Muscle. Adv. Mater. Technol. 1, 1600055 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help of Dr. Teng Zhang of the School of Astronautics in Northwestern Polytechnical University for assistance in the experiments. The authors thank Dr. Majid Taghavi of the Department of Bioengineering in Imperial College London and Prof. Jonathan Rossiter of the Department of Engineering Mathematics in University of Bristol for their replies to our questions about electro-ribbon. This work was supported by Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (X.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: X.W. and Y.W.; Methodology: X.W., Y.W., and M.Z.; Investigation: X.W., Y.W., M.Z.; Visualization: Y.W. and X.W.; Funding acquisition: X.W. and X.Y.; Project administration: X.W. and X.Y.; Supervision: X.W., X.Y.; Writing—original draft: X.W. and Y.W.; Writing—review and editing: X.W., Y.W., M.Z., X.Y.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Thorsten Kern and Dylan Shah for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Wang, Y., Zhu, M. et al. 2-dimensional impact-damping electrostatic actuators with elastomer-enhanced auxetic structure. Nat Commun 15, 7333 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51787-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51787-8

This article is cited by

-

Monolithic electrostatic actuators with independent stiffness modulation

Nature Communications (2025)