Abstract

High-quality superconductor/topological material heterostructures are highly desired for realisation of topological superconductivity and Majorana physics. Here, we demonstrate a method to directly draw nanoscale superconducting β-Sn patterns in the plane of a topological Dirac semimetal (TDS) α-Sn thin film by irradiating a focused ion beam and taking advantage of the heat-driven phase transition of α-Sn into superconducting β-Sn. The β-Sn nanowires embedded in a TDS α-Sn thin film exhibit a large superconducting diode effect (SDE), whose rectification ratio η reaches a maximum of 35% when the magnetic field is applied parallel to the current. The results suggest that the SDE may occur at the α-Sn/β-Sn interfaces where the TDS α-Sn becomes superconducting by a proximity effect. Our work thus provides a universal platform for investigating quantum physics and devices based on topological superconducting circuits of any shape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological superconductors garner significant attention as a crucial pathway for realising Majorana quasiparticles, which are highly sought-after yet enigmatic candidates for quantum bits in fault-tolerant quantum computing1,2,3,4. To date, extensive research on topological superconductivity has focused on heterostructures of topologically nontrivial materials, such as topological insulators5,6, TDS7,8, and topological Weyl semi-metals9,10, in conjunction with conventional s-wave superconductors, exploiting the superconducting proximity effect5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. To achieve a material platform for large-scale quantum computing, the critical challenges in such heterostructures are establishing high-quality interfaces between topological materials and superconductors while utilising cost-effective and scalable processes for material growth and nanofabrication. Given that many candidate topological materials are relatively new and immature, meeting these requirements presents a significant challenge for materials science and device engineering.

This work introduces a topological material platform based on Sn, one of human history’s earliest-known and most commonly used metal elements. Body-centred tetragonal β-Sn is a well-known metal that exhibits conventional BCS-type superconductivity below 4 K. On the other hand, α-Sn, with a diamond-type crystal structure, behaves as a Luttinger semimetal with no band gap in bulk. However, under tensile or compressive strain, it can transform into a three-dimensional topological insulator (3D-TI) or a TDS, respectively. Notably, TDSs16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 feature 3D linear-dispersion Dirac cones with strong spin-orbit-momentum locking, leading to exotic phenomena such as Fermi arcs on the surface and chiral anomaly. Both the 3D Luttinger semimetal and TDS have been theoretically predicted to become topological superconductors capable of hosting Majorana quasiparticles in their superconducting states26,27,28.

Among the rare examples of experimentally confirmed TDSs16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, α-Sn16,21,22,23 stands out as the only elemental material that can be grown with exceptional quality on semiconductor substrates like InSb or CdTe. Furthermore, α-Sn undergoes a phase transition to β-Sn upon heating, providing a new avenue to introduce superconductivity into the already-rich topological phase diagram of α-Sn. This study presents a method to incorporate superconductivity into the topological platform of α-Sn, forming arbitrary planar shape patterns on the nanometre scale. Using a Ga-focused ion beam (FIB), we directly draw nm-scale β-Sn patterns onto TDS α-Sn thin films, inducing a phase transition from α-Sn to superconducting β-Sn upon FIB irradiation. While previous reports have utilised ion beams to partially destroy superconductors and create insulating layers for fabricating Josephson junctions29,30,31,32, our approach results in superconducting β-Sn regions within the TDS α-Sn films with high-quality interfaces. As will be shown in this work, β-Sn superconducting nanowires embedded in α-Sn exhibit remarkable phenomena. When a moderate in-plane magnetic field is applied, we observe: i) unconventional superconductivity with a two-fold symmetric angular dependence of the critical current (IC), and ii) giant non-reciprocal superconducting transport, where the superconducting diode rectification ratio η reaches 35% when the magnetic field is parallel to the current. These unprecedented observations suggest that the combination of TDS and superconductivity in Sn plays a pivotal role in accessing topological superconducting functionalities. By leveraging these FIB-patterned Sn-based planar structures, we can establish a versatile superconductor/topological material platform for high-quality superconducting circuits of arbitrary shapes; all achieved through remarkably simple processes.

Results

Sample preparation and characterisation

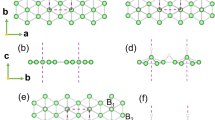

We epitaxially grew 70 nm-thick α-Sn thin films on InSb (001) substrates using molecular-beam epitaxy (see Methods). The growth conditions were the same as our previous study16, where α-Sn exhibited TDS behaviour due to compressive strain in the in-plane direction. Subsequently, the α-Sn thin film was partially irradiated with a FIB, employing a Ga ion beam accelerated with a voltage of 30 kV and a pitch interval of 5 nm in a serpentine scanning mode (Fig. 1a, see also “Methods”). The irradiated areas of TDS α-Sn were immediately transformed into β-Sn, easily distinguishable by its metallic silver colour in contrast to the dark grey colour of the surrounding α-Sn regions. We conducted density of states (DOS) measurements at the Fermi level (EF) for both the as-grown α-Sn and the FIB-irradiated Sn using X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) at 300 K. The results display a clear difference, as illustrated in Fig. 1d: The as-grown α-Sn exhibits vanishingly small DOS at EF, typical of a semi-metal, while the irradiated Sn area shows a much larger DOS with a Fermi-Dirac edge, similar to that of a reference Au thin film, indicating the expected metallic band structure of β-Sn.

a Schematic image of α-Sn/β-Sn planar nanostructures fabricated by FIB irradiation. b, c Top-view scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of (b) β-Sn/α-Sn/β-Sn Josephson junction structure with an α-Sn width of 70 nm and (c) a 180 nm-wide β-Sn nanowire embedded in α-Sn (see “Methods”). d X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) measurements of the valence band spectrum of α-Sn and β-Sn regions, compared with an Au reference film. The Fermi level EF (vertical red line) is determined from the Fermi-Dirac edge of the Au film. A large DOS is detected at EF of the irradiated Sn, reflecting the metallic behaviour of β-Sn. e Cross-sectional scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) lattice image of the interface region between α-Sn/β-Sn prepared by FIB irradiation. The as-grown α-Sn retains its diamond-type crystal structure (yellow-square inset), while the FIB-irradiated region changes to polycrystalline β-Sn (red-square inset). An abrupt interface between α-Sn/β-Sn region is obtained. f Temperature dependence of the resistance of the β-Sn wires with various wire widths. Inset shows the detailed data around the superconducting transition. All the wires undergo a superconducting transition below 4 K.

For further characterisation of the α-Sn/β-Sn planar structures, we employed microscopic techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). Top-view SEM images illustrate two typical structures: a planar β-Sn/α-Sn/β-Sn junction (Fig. 1b) and a β-Sn nanowire embedded in α-Sn (Fig. 1c). The β-Sn nanowire, fabricated by irradiating Ga ions with a designed line width W0 of 10 nm, exhibits an actual width W of 180 nm. It is important to note that the β-Sn wire width W is approximately 170 nm larger than the irradiated width W0, owing to the lateral diffusion of heat generated by the Ga ion collision, which additionally induced a phase transition in the α-Sn on both sides. This scenario is confirmed through the cross-sectional STEM image of a nanowire shown in Fig. 1e (see also Supplementary Figs. 1, 2): The β-Sn region consists of a centre part with grain boundaries, where the Ga ions directly collided, and two clean polycrystalline parts extending 150–200 nm on each side, that are likely formed due to thermal diffusion. The α-Sn/β-Sn interface is found to be atomically abrupt and of high quality. Taking into account the heat-induced expansion of the β-Sn area, we successfully fabricated a planar β-Sn/α-Sn/β-Sn junction with the actual width of the α-Sn channel measuring 70 nm (Fig. 1b), using a designed value of 200 nm. As a result, through simulation and optimising the patterning design, our FIB method enables the fabrication of any nanoscale planar structures of α-Sn and β-Sn.

Observation of superconducting diode effect

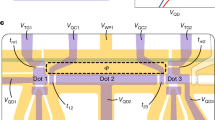

Next, we investigated the superconducting properties of the α-Sn/β-Sn planar heterostructures. Three β-Sn nanowires with actual widths W = 500, 1000, and 2000 nm were fabricated along the \([1\bar{1}0]\) axis on a single α-Sn film, all of which exhibited superconductivity below 4 K, as illustrated in Fig. 1f. The resistance displays an anomalous rise just before dropping to zero at the superconducting transition around 3.7 K. This behaviour can be attributed to a decrease in the DOS near EF when Cooper pairs are formed in the α-Sn due to the superconducting proximity effect at the α-Sn/β-Sn interface33. Interestingly, we observe a giant superconducting diode effect (SDE) in all three β-Sn nanowires when a magnetic field is applied parallel and antiparallel to the current at 2 K. Figure 2a shows the resistance – current characteristics in the β-Sn nanowire with W = 500 nm (which we name NW90). When a magnetic field H = ± 0.1 T is applied parallel to the nanowire, the critical current IC increases when the current I and H are parallel (IC+) and decreases significantly when I and H are antiparallel (IC−). As shown in Fig. 2a, IC = 62 µA at H = 0 (black curve), IC+ = –70 µA and IC− = 34 µA at H = 0.1 T (green curve), thus the diode ratio η = ||IC+|–|IC−||/(|IC+|+|IC−|) is as large as 35%, which is among the largest SDEs reported thus far. The superconducting diode operation is demonstrated by switching the current at ± 68 μA under a fixed H = 0.11 T, as shown in Fig. 2b. The nanowire’s resistance alternates between zero and a nonzero finite value of 1.6 Ω, indicating a successful demonstration of a superconducting diode operation. η increases monotonically as H is increased, reaching a maximum value of 35% around 0.1 T then decreases monotonically to zero at around 0.2 T (Fig. 2c).

a Current dependence of the resistance of a β-Sn/α-Sn nanowire (NW90) with a width W = 500 nm when a magnetic field H is applied parallel (orange) and antiparallel (green) to the current I. b Switching between the superconducting and normal-conducting states by changing the direction of the applied current between ± 68 μA, while a magnetic field H = 0.11 T is applied parallel to current direction. c Absolute values of the diode rectification ratio η (top) and critical current IC (bottom) as functions of the magnetic field strength with H // I. η reaches a maximum value of 35% when H = −0.1 T. All are measured at 2 K.

Discussion

SDE has been recently reported in many material systems, and its mechanisms are subjects of active debates34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. In all previous systems, SDE occurs when an applied magnetic field (H) is orthogonal to the current (I), regardless of whether the proposed mechanisms are intrinsic34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 or extrinsic48,49. However, the non-reciprocal superconductivity in our β-Sn wires embedded in α-Sn represents the first instance of giant SDE realised when H and I are parallel, a completely different result. To elucidate the mechanism in the Sn-based nanowires, we investigate the dependence of the superconducting critical current IC (IC+, IC−) on the directions of H and I. As depicted in Fig. 3, we patterned three β-Sn nanowires (NW0, NW45, NW90) with the same width (W = 500 nm) in a 70 nm-thick α-Sn thin film along three different crystallographic axes of the InSb (001) substrate: [110], [100], and \([1\bar{1}0]\), respectively. We measured IC while rotating the nanowires in a fixed H ( = 0.056, 0.185, 0.110 T for NW0, NW45, and NW90, respectively) so that H remained in the film plane, all at 2 K. In Fig. 3, we show the even component (IEVEN = (IC+ + IC-)/2) and the odd component (IODD = | IC+ – IC- | /2) of IC separately. Hereafter, IC+ and IC- denote absolute values. The first crucial observation is that the symmetry of IEVEN and IODD is similar in all three nanowires, determined solely by the angle θ between H and I, and is unrelated to the crystallographic axis. As shown in Fig. 3, both IEVEN and IODD can be well-fitted by functions of θ as follows:

where A, B, C, and D represent fitting parameters (see Supplementary Table 1 for detailed fitting parameters). Remarkably, both IEVEN and IODD, which measure the absolute value of the superconducting critical current and its non-reciprocity, respectively, exhibit a surprisingly acute dependence on θ that can only be fitted by fourth-power cosine functions. This characteristic behaviour is typical of the magnetic chiral effect (MCE) observed in topological Dirac/Weyl semi-metals, originating from the chiral anomaly effect between 3D Dirac/Weyl cones with opposite chirality19,20,25,50. The cos4θ-dependence has been theoretically predicted50 and observed in the MCE of a TDS, Na3Bi51, where the magnetoconductance varies as cos4θ at magnetic fields lower than 2 T. The very similar dependence on current and magnetic field directions between the critical current (IC) in β-Sn/α-Sn nanowires and the magnetoconductance in TDSs strongly suggests that the TDS α-Sn areas play an important role in the superconductivity of the studied nanowires. It is noteworthy that although superconductivity has been realised in another TDS, Cd3As2, such a strong manifestation of TDS properties in the superconductivity has never been reported.

We prepared and measured superconducting critical currents in three β-Sn/α-Sn nanowires (W = 500 nm, namely NW0, NW45, NW90) oriented along three different crystallographic axes of [110], [100] and \([1\bar{1}0]\), respectively. The magnetic-field angular dependence of the even component IEVEN (blue data points) and the odd component IODD (red data points) of the critical currents show different symmetries, which can be fitted as functions of θ, the angle between H and I, using Eqs. (1, 2). Blue and red triangles point to the two-fold symmetry axes of the even and odd components, respectively. Fixed values of H ( = 0.056, 0.185, 0.110 T for NW0, NW45, and NW90, respectively) are applied. All are measured at 2 K.

Additionally, other intriguing observations from Fig. 3 pertain to the symmetry of IEVEN and IODD. The critical current of β-Sn/α-Sn nanowires, measured by IEVEN, exhibits significant two-fold anisotropy when H is rotated by 45° and 225° with respect to I. This two-fold symmetric anisotropy in IEVEN cannot be explained by the geometry of the β-Sn nanowires, which have no asymmetry along the θ = 45° and θ = 135° directions. This may possibly reflect an anisotropic strength of the pairing potential of Cooper pairs, likely stemming from the distinct spin-orbit-momentum textures and DOS at EF when the configuration between H and I changes. Theoretical predictions have suggested anisotropic superconducting pairing potential and nodal superconducting gap structures for TDSs27,28, which might be related to the observed anisotropic IEVEN. Meanwhile, the non-reciprocal component IODD also shows substantial enhancements when θ = 0° (H // I) and θ = 112°. The fact that superconducting nonreciprocal transport can occur when H // I is a feature that has never been observed in other systems, and it is somewhat expected as the chiral anomaly effect is known to occur at this configuration in topological Dirac/Weyl semimetals. On the other hand, the observation that η reaches maximum at θ = 112° in the odd component is not expected from any known symmetry of the α-Sn/β-Sn nanowire system. Furthermore, as can be seen in Fig. 3, the magnitude of η around θ = 112° is not as robust as that around θ = 0 and 45° and is especially small for NW45. This indicates that the origin of the superconducting diode effect at θ = 112° may be different. To explain the angular dependence of IEVEN and IODD, theoretical models accounting for the special spin-orbit-momentum texture in TDSs, particularly α-Sn, are strongly desired.

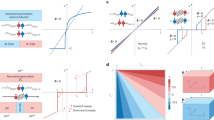

To gain insights into why the TDS properties of α-Sn strongly influence the superconductivity in the β-Sn nanowires, we explore the nanowire-width (W) dependence of the superconducting transport properties. As shown in Fig. 4a, in three nanowires with W = 500, 1000, and 2000 nm, the values of IC in both positive and negative directions (IC+, IC-) increase linearly with W, because the same current density is required to reach the superconducting depairing limit. However, the non-reciprocal component IODD (= |IC+ – IC- | /2 = ΔIC/2) exhibits weak dependence on W, suggesting that the SDE predominantly occurs at the edge of the β-Sn nanowires, precisely at the interfaces between β-Sn and α-Sn. According to the STEM results, the β-Sn nanowires consist of a disordered centre part with a width W0, formed by direct collisions with Ga ions, and disorder-free edge parts, formed by thermal diffusion on both edges (see Supplementary Fig. 1). SEM images of the three nanowires in Fig. 4a confirm W ≈ W0 + 150 nm, indicating that the thermally formed β-Sn region is approximately 75 nm wide on each side (see thermally formed β-Sn in Fig. 4b, orange coloured). Furthermore, the α-Sn regions facing the nanowire edges also become superconducting (SC) due to the proximity effect from the adjacent β-Sn (see proximitised SC α-Sn in Fig. 4b, green-yellow coloured). Based on the width dependence of IC, we propose that the non-reciprocal superconducting transport occurs at these thermally formed β-Sn / proximitised SC α-Sn edge channels. This edge transport scenario is reasonable for the following three reasons: i) The better crystal quality and absence of ion-impacted damages in the edge regions guarantee stronger superconductivity at the edges compared with the centre part. ii) Only at the β-Sn/α-Sn interface is the inversion symmetry is broken, a prerequisite for non-reciprocal transport. iii) The observed superconducting transport in our nanowires closely resembles the MCE in TDS, which can only be explained by the contribution from adjacent superconducting α-Sn. Overall, our findings suggest that the non-reciprocal superconducting transport in the β-Sn nanowires is intimately related to the presence of high-quality α-Sn/β-Sn interfaces at the edges, highlighting the significance of these interfaces in enabling topological superconductivity.

a Width dependence of the critical currents in the positive direction IC+ and negative direction IC− (left axis), and their difference, \(\Delta {I}_{{\mbox{C}}}={I}_{C+}-{I}_{C-}\) (right axis). b Schematic view of the β-Sn/α-Sn planar structure deduced from the results in (a). The β-Sn nanowires contain a disordered centre part (grey-coloured) with a width W0 formed by direct collisions with the Ga ions and disorder-free edge regions (orange-coloured) formed by thermal diffusion in both edges. Furthermore, the α-Sn areas that face the nanowire edges also become superconducting due to a proximity effect from β-Sn (green-yellow coloured). The total thickness of the thermally formed β-Sn and the proximitised superconducting (SC) α-Sn on each side is W*, which is about 150 nm. c Dependence of the critical currents in the positive direction IC+ and in the negative direction IC−, and η on the magnetic field strength in NW0 when H is applied parallel to I. Strong and uniform oscillations with a period ΔH = 2400 Oe are observed, and η changes its sign at the half-period ΔH /2 = 1200 Oe. All are measured at 2 K.

Another hallmark of the SDE, predicted in theoretical models36,44,45,46,47, is the sign reversal of η with increasing magnetic field strength H. Although this behaviour has been observed in a few recent experiments, it remained quite subtle52,53. As depicted in Fig. 4c, in our β-Sn/α-Sn nanowire NW0 (W = 500 nm), IC+, IC-, and η exhibit strong and uniform oscillations with a period ΔH = 2400 Oe, with η changing sign at a half-period ΔH/2 = 1200 Oe when a parallel H is applied. The theories on noncentrosymmetric superconductors typically explain the sign reversal of η as a change in the nature of the helical superconducting state, but this is not accompanied by the strong oscillations in IC36,44,45,46. Conversely, the oscillatory behaviour of IC with H has been observed in Josephson junctions of a TDS consisting of Nb/Cd3As2/Nb when H is applied parallel to I across the junction54. This phenomenon was explained as an orbital effect when magnetic fluxes from H thread through a trajectory of the currents travelling between the bulk (Dirac cones) and surface (Fermi arcs) states of the TDS. Furthermore, in topological Dirac/Weyl semi-metals, the superconducting current can be carried separately in the bulk states and in the surface states54,55, with the latter typically exhibiting stronger superconductivity due to higher mobility and robustness against disorder scattering. In our Sn nanowires, with a London penetration depth of β-Sn being 36 nm56, the magnetic fluxes from a parallel H can penetrate the entire thickness (70 nm) of the β-Sn/α-Sn edge channels, assuming that the London penetration depth of the superconducting α-Sn (proximitised by the superconducting β-Sn) is the same as that of β-Sn. In this case, the value of ΔH = 2400 Oe corresponds to a magnetic flux quantum ϕ0 (=2.0 × 10−15 Wb) threading through a cross-sectional area of a hypothetical Sn-based nanowire with a width W* = 150 nm and a film thickness of 70 nm in sample NW0. Although W* is much smaller than W = 500 nm in NW0, it closely matches the width of the β-Sn/α-Sn edge channels, comprising the 75 nm-wide thermally formed β-Sn and the proximitised SC α-Sn with a typical width of ~100 nm. These dimensions thus suggest that the SDE occurs in the superconducting edge channels of α-Sn/β-Sn with a total width W* = 150 nm and a film thickness of 70 nm, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. In this scenario, the discrete penetration of magnetic flux quanta leads to an oscillation with a period of ϕ0 (ΔH = 2400 Oe) and a sign reversal at ϕ0/2 (ΔH/2 = 1200 Oe) in the SDE rectification ratio η, as predicted in a recent theory for SDE in a superconducting 1D chiral nanotube47. Furthermore, the oscillatory behaviour of IC and η as a function of H suggests that the non-reciprocal superconducting transport primarily originates from the superconducting transport in the surface states of the TDS α-Sn, induced by a proximity effect from the β-Sn. Nevertheless, further theoretical investigations are undoubtedly needed to fully understand the mechanism of SDE demonstrated in our Sn-based nanowires.

In conclusion, using FIB, we have demonstrated a universal and cost-effective method for fabricating nanoscale Sn-based superconductor / TDS planar heterojunctions of arbitrary shapes. The combination of superconductivity and TDS properties led to observing a large SDE in the β-Sn/α-Sn nanowires when H is parallel to I, a remarkable finding not reported before. The SDE’s controllability by a magnetic field and its independence of the crystallographic axis, likely arising from a chiral anomaly in TDS α-Sn, offer non-volatile control when interfacing the structure with a ferromagnetic material and a high degree of freedom in embedding superconducting diodes in various designs for future quantum computing circuits. In a broader context, Sn-based superconductor / TDS heterostructures hold promise as a promising platform for topological superconductor devices and topological quantum circuitry, enabling nanoscale fabrication of various shapes through direct drawing with an ion beam.

Methods

Sample growth

The single-crystalline α-Sn thin film was epitaxially grown on an InSb (001) substrate using low-temperature molecular-beam epitaxy. First, a 100 nm-thick InSb buffer layer was grown on the InSb (001) substrate. Subsequently, the substrate holder was cooled to –10 °C, and a 70 nm-thick α-Sn film was grown at a growth rate of 10 Å/min (sample A). The existence and good quality of α-Sn were confirmed by TEM, X-ray diffraction (XRD) and transport measurements (see Supplementary Note 1 for XRD and transport results). As shown in Fig. 1e, α-Sn was epitaxially grown while maintaining a diamond-type crystal structure that is indistinguishable from the zinc-blende-type crystal structure of the InSb buffer layer, and β-Sn(100) atomic layers can be seen in the polycrystalline β-Sn region. The atomic layer interval of β-Sn(100) is estimated to be 3.56 Å from the TEM lattice image, which is close to the typical atomic layer interval of β-Sn(100) of 3.23 Å. The reason for the slight deviation is that the β-Sn region is polycrystalline, and the crystal grains are slightly tilted. We note that it is challenging to take good TEM images of the Sn heterostructures, because heating effect during preparation of the TEM specimen may yield unwanted effects.

For a better TEM characterisation, we grew a new sample (sample B) of 50 nm-thick α-Sn on InSb with the same condition as the abovementioned sample A. We designed a smaller thickness (50 nm, in comparison with the thickness of 70 nm in sample A) to enhance the thermal stability of the α-Sn layer. Note that these thicknesses are supposed to make the α-Sn layer in both samples become topological Dirac semimetal under an in-plane compressive strain16. After irradiating the sample B with a focused Ga ion beam to fabricate superconducting nanowires, TEM characterisation of the β-Sn/α-Sn samples was conducted as soon as possible (within two days), with special care to avoid heating effect during fabrication and measurements. The TEM results are given in Supplementary Fig. 2. The cross-sectional TEM image of the α-Sn/β-Sn interface indicates an atomically sharp and clean interface between α-Sn and β-Sn. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows the transmission electron diffraction (TED) images of as-grown α-Sn and the InSb buffer layer. α-Sn and InSb show diffraction patterns of diamond-type and zinc-blende-type crystal structures, respectively, which are consistent with the cross-sectional TEM lattice image results.

Device fabrication

The β-Sn wire structures were fabricated by irradiating a Ga-focused ion beam using a V400ACE FIB system made by FEI Company Japan Ltd. An acceleration voltage of 30 kV and a current of 7.7 pA were used for the ion beam with a beam size of 5 nm in all devices. The crystal structure of the FIB-irradiated β-Sn was characterised using TEM (see Fig. 1e, Supplementary Figs. 1, 2), electron backscattering diffraction (EBSD) measurements (see Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Figs. 6). After being irradiated by Ga ions, the α-Sn region is transformed to β-Sn due to the ion beam impact and its local heating effect. The penetration of Ga ions in Sn was simulated using Stopping Range of Ions in Matter (SRIM) software and discussed in Supplementary Note 3. From the TEM results, we estimated the lattice constants of α-Sn at positions close to and away from the α-Sn/β-Sn interface and found that both lattice constants are equivalent. This result indicates that the α-Sn layer is subjected to in-plane compressive strain in the whole area and remains in the topological Dirac/Weyl semimetal phase. It seems that local strain at the interface is not present because the α-Sn/β-Sn interface is fully relaxed (see Supplementary Note 4).

For transport measurements, electrodes for four-terminal measurements were formed on the nanowires (see Supplementary Fig. 8), all fabricated by FIB irradiation. The nanowire part has a length of 20 μm and a variable width W. The actual width W of the β-Sn nanowires was measured using SEM, indicating that the β-Sn region induced by thermal diffusion is expected to be about 75 nm on each side. The β-Sn nanowire structures with widths of W = 500, 1000, and 2000 nm were fabricated by irradiating FIB in regions with initial widths (W0) of 350, 850, and 1850 nm, respectively. XPS measurements confirmed that no detectable Ga or In remained in the irradiated Sn areas above a threshold of 0.1 atom%, indicating that there is no influence of the Ga ions from the ion beam or In diffused from InSb on the sample surface57.

Transport measurements

Direct current transport measurements were conducted using a Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System. A sample holder equipped with a rotator was utilised, and the critical current was measured while incrementally rotating the sample in an in-plane magnetic field by 360° at 5° intervals.

Critical current and non-reciprocal component of superconducting β-Sn wires

Both positive and negative critical currents were measured by sweeping the current from zero to eliminate the effect of heat generation in the normal conduction state. The critical current is defined as the value just before the resistance increases when the current is increased from zero. Initially, we investigated the dependence of the η value on the applied magnetic field H when H is parallel to I. The critical currents of the β-Sn wires with different widths shown in Fig. 4a and the in-plane magnetic field angle dependence of non-reciprocal superconductivity shown in Fig. 3 were measured at a fixed magnetic field strength H for each wire where η reaches its maximum.

The magnetic field dependence of the critical current in Fig. 2c was plotted from separate measurements at different magnetic fields in which the direction of current I is reversed in the positive and negative directions. The measurement procedure is a repetition of i) applying the magnetic field at 2 K (superconducting state) and measuring the critical current in the positive and negative directions from zero bias current, ii) plotting η, and iii) changing the magnetic field. The magnetic field H was changed from −4000 Oe to 4000 Oe, while the temperature was always kept at 2 K. Because we applied H parallel to I, the magnetic flux was expected to penetrate the whole thickness of the Sn layer (70 nm), considering the London penetration depth of β-Sn being 36 nm56. In the configuration of H//I, there is no Lorentz driving force exerting on the vortices. This means that the vortex pinning is not a relevant mechanism to explain our superconducting diode effect.

Superconducting diode effect under a perpendicular magnetic field

Unintentional tilt of the sample can affect the in-plane magnetic field angular dependence of the nonreciprocal superconductivity shown in Fig. 3. To exclude this possibility, we measured the superconducting diode effect when the magnetic field H was applied perpendicular to the film plane. Supplementary Fig. 9 shows the magnetic field dependence of the diode rectification ratio η in that case, measured at 2 K. For this measurement, a β-Sn nanowire with a width of 500 nm in the [110] direction was fabricated on the same α-Sn sample under the same FIB processing conditions as those in the main text. Although η oscillates and changes sign with respect to the perpendicular magnetic field, the maximum η magnitude is only 4%, which is much smaller than that (~35%) in the case of applying an in-plane magnetic field. Therefore, even if there was a small out-of-plane magnetic field component in our measurements with an in-plane magnetic field, its effect on the superconducting diode effect would be limited and cannot yield the large peak around η = 30% at θ = 0 and 112°, as observed in Fig. 3.

To check whether there is any effect of vortex pinning or not in our samples, we measured the magnetic susceptibility of the β-Sn/α-Sn structure in a perpendicular magnetic field using two protocols, field cooling the zero-field cooling, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10 (see Supplementary Information). The sample was cooled to 2 K with or without a perpendicular magnetic field H of 5 mT, then the magnetisation was measured with increasing temperature under H of 5 mT. As can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 10, the magnetic susceptibility measured by both protocols shows almost the same result, indicating that the effect of vortex pinning in our β-Sn/α-Sn structure is negligible. Temperature dependence of the perpendicular critical magnetic field of the FIB-irradiated Sn is shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. By fitting a 2D superconductor model (red curve) to the experimental result (blue solid circles), we obtain a Ginzburg - Landau coherence length ξGL of 55 nm.

Data availability

The source data for Figs. 1d,f, 2a–c, 3, 4a,c in this study are available in the Zenodo database with the following url: https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.13322478. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Kitaev, A. Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys. -Uspekhi 44, 131–136 (2001).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Sarma, S., Das, Freedman, M. & Nayak, C. Majorana zero modes and topological quantum computation. Npj Quantum Inf. 1, 15001 (2015).

Sato, M. & Ando, Y. Topological superconductors: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 076501 (2017).

Wang, M.-X. et al. The coexistence of superconductivity and topological order in the Bi2Se3 thin films. Science 336, 52–55 (2012).

Wiedenmann, J. et al. 4π-periodic Josephson supercurrent in HgTe-based topological Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 7, 10303 (2016).

Huang, C. et al. Proximity-induced surface superconductivity in Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Commun. 10, 2217 (2019).

Li, N. et al. Gate modulation of anisotropic superconductivity in Al–Dirac semimetal Cd3As2 nanoplate–Al Josephson junctions. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 35, 044003 (2022).

Huang, C. et al. Inducing strong superconductivity in Wte2 by a proximity effect. ACS Nano 12, 7185–7196 (2018).

Li, Q. et al. Proximity-induced superconductivity with subgap anomaly in type II Weyl semi-metal Wte2. Nano Lett. 18, 7962–7968 (2018).

Das, A. et al. Zero-bias peaks and splitting in an Al-InAs nanowire topological superconductor as a signature of Majorana fermions. Nat. Phys. 8, 887–895 (2012).

Deng, M. T. et al. Anomalous zero-bias conductance peak in a Nb-InSb nanowire-Nb hybrid device. Nano Lett. 12, 6414–6419 (2012).

Leijnse, M. & Flensberg, K. Introduction to topological superconductivity and Majorana fermions. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 27, 124003 (2012).

Frolov, S. M., Manfra, M. J. & Sau, J. D. Topological superconductivity in hybrid devices. Nat. Phys. 16, 718–724 (2020).

Kezilebieke, S. et al. Topological superconductivity in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 588, 424–428 (2020).

Anh, L. D. et al. Elemental topological Dirac semimetal α‐Sn with high quantum mobility. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104645 (2021).

Wang, Z., Weng, H., Wu, Q., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Three-dimensional Dirac semimetal and quantum transport in Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125427 (2013).

Liu, Z. K. et al. Discovery of a three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal, Na3Bi. Science 343, 864–867 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. Dirac semimetal and topological phase transitions in A3Bi (A = Na, K, Rb). Phys. Rev. B 85, 195320 (2012).

Feng, J. et al. Large linear magnetoresistance in Dirac semimetal Cd3As2 with Fermi surfaces close to the Dirac points. Phys. Rev. B 92, 081306 (2015).

Ohtsubo, Y., Le Fèvre, P., Bertran, F. & Taleb-Ibrahimi, A. Dirac cone with helical spin polarization in ultrathin α-Sn(001) films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 216401 (2013).

Barfuss, A. et al. Elemental topological insulator with tunable Fermi level: Strained α-Sn on InSb(001). Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 157205 (2013).

Scholz, M. R. et al. Topological surface state of α−Sn on InSb(001) as studied by photoemission. Phys. Rev. B 97, 075101 (2018).

Rojas-Sánchez, J.-C. et al. Spin to charge conversion at room temperature by spin pumping into a new type of topological insulator: α -Sn films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 096602 (2016).

Uchida, M. et al. Quantum hall states observed in thin films of Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Commun. 8, 2274 (2017).

Roy, B., Ghorashi, S. A. A., Foster, M. S. & Nevidomskyy, A. H. Topological superconductivity of spin-3/2 carriers in a three-dimensional doped Luttinger semimetal. Phys. Rev. B 99, 054505 (2019).

Kobayashi, S. & Sato, M. Topological Superconductivity in Dirac Semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 187001 (2015).

Hashimoto, T., Kobayashi, S., Tanaka, Y. & Sato, M. Superconductivity in doped Dirac semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 94, 014510 (2016).

Burnell, G. et al. Planar superconductor-normal-superconductor Josephson junctions in MgB2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 3464–3466 (2001).

Wu, C. H. et al. Fabrication and characterization of high- Tc Yba2Cu3O7−x nano SQUIDs made by focused ion beam milling. Nanotechnology 19, 315304 (2008).

Wu, C.-H. et al. Fabrication and properties of high-Tc YBCO Josephson junction and squid with variable thickness bridges by focused ion beam. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 21, 375–378 (2011).

Müller, B. et al. Josephson junctions and SQUIDs created by focused Helium-ion-beam irradiation of Yba2Cu3O7. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 044082 (2019).

Gál, N., Štrbík, V., Gaži, Š., Chromik, Š. & Talacko, M. Resistance anomalies at superconducting transition in multilayer N/S/F/S/N heterostructures. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 32, 213–217 (2019).

Ando, F. et al. Observation of superconducting diode effect. Nature 584, 373–376 (2020).

Jiang, K. & Hu, J. Superconducting diode effects. Nat. Phys. 18, 1145–1146 (2022).

Yuan, N. F. Q. & Fu, L. Supercurrent diode effect and finite-momentum superconductors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2119548119 (2022).

Lin, J.-X. et al. Zero-field superconducting diode effect in small-twist-angle trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 18, 1221–1227 (2022).

Pal, B. et al. Josephson diode effect from Cooper pair momentum in a topological semimetal. Nat. Phys. 18, 1228–1233 (2022).

Baumgartner, C. et al. Supercurrent rectification and magnetochiral effects in symmetric Josephson junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 39–44 (2022).

Bauriedl, L. et al. Supercurrent diode effect and magnetochiral anisotropy in few-layer NbSe2. Nat. Commun. 13, 4266 (2022).

Wu, H. et al. The field-free Josephson diode in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 604, 653–656 (2022).

Gupta, M. et al. Gate-tunable superconducting diode effect in a three-terminal Josephson device. Nat. Commun. 14, 3078 (2023).

Matsuo, S., et al. Josephson diode effect derived from short-range coherent coupling. Nature Phys. (2023).

Daido, A., Ikeda, Y. & Yanase, Y. Intrinsic superconducting diode effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 037001 (2022).

Ilic, S. & Bergeret, F. S. Theory of the supercurrent diode effect in Rashba superconductors with arbitrary disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 177001 (2022).

He, J. J., Tanaka, Y. & Nagaosa, N. A phenomenological theory of superconductor diodes. N. J. Phys. 24, 053014 (2022).

He, J. J., Tanaka, Y. & Nagaosa, N. The supercurrent diode effect and nonreciprocal paraconductivity due to the chiral structure of nanotubes. Nat. Commun. 14, 3330 (2023).

Hou, Y. et al. Ubiquitous superconducting diode effect in superconductor thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 027001 (2023).

Suri, D. et al. Non-reciprocity of vortex-limited critical current in conventional superconducting micro-bridges. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 102601 (2022).

Burkov, A. A. & Kim, Y. B. Z2 and chiral anomalies in topological Dirac semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 136602 (2016).

Jun, X. et al. Evidence for the chiral anomaly in the Dirac semimetal Na3Bi. Science 350, 413–416 (2015).

Kawarazaki, R. et al. Magnetic-field-induced polarity oscillation of superconducting diode effect. Appl. Phys. Express 15, 113001 (2022).

Margineda, D. et al. Sign reversal diode effect in superconducting Dayem nanobridges. Commun. Phys. 6, 343 (2023).

Li, C. Z. et al. Fermi-arc supercurrent oscillations in Dirac semimetal Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 11, 1150 (2020).

Kuibarov, A. et al. Evidence of superconducting Fermi arcs. Nature 626, 294–299 (2024).

Kozhevnikov, V. et al. Nonlocal effect and dimensions of Cooper pairs measured by low-energy muons and polarized neutrons in type-I superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 87, 104508 (2013).

Inagaki, K. et al. Allotropic transition of Dirac semimetal alpha-Sn to superconductor beta-Sn induced by irradiation of focused ion beam. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 021602 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grants No. 20H05650, No. 23K17324, and No. 24H00018), CREST programme (JPMJCR1777) and PRESTO Programme (JPMJPR19LB) of JST, UTEC-UTokyo FSI, Murata Science Foundation and Spintronics Research Network of Japan (Spin-RNJ). A part of this work was supported by “Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology in Japan (ARIM)” of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D.A. and M.T. supervised the study. L.D.A. and K.I. conceived and designed the experiments. T.H. and H.M. performed the growth and characterisation of the α-Sn thin film. K.I. and M.K. carried out XPS measurements. K.I. fabricated β-Sn wire devices using FIB and measured the transport properties. L.D.A. and K.I. carried out the data analysis. T.S. carried out SRIM simulation. L.D.A., K.I. and M.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors thoroughly discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks David Cortie, Wenlong Yu and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anh, L.D., Ishihara, K., Hotta, T. et al. Large superconducting diode effect in ion-beam patterned Sn-based superconductor nanowire/topological Dirac semimetal planar heterostructures. Nat Commun 15, 8014 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52080-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52080-4

This article is cited by

-

Josephson diode effect in nanowire-based Andreev molecules

Communications Physics (2025)