Abstract

Resistive memory devices feature drastic conductance change and fast switching dynamics. Particularly, nonvolatile bipolar switching events (set and reset) can be regarded as a unique nonlinear activation function characteristic of a hysteretic loop. Upon simultaneous activation of multiple rows in a crosspoint array, state change of one device may contribute to the conditional switching of others, suggesting an interactive network existing in the circuit. Here, we prove that a passive resistive switching circuit is essentially an attractor network, where the binary memory devices are artificial neurons while the pairwise voltage differences define an anti-symmetric weight matrix. An energy function is successfully constructed for this network, showing that every switching in the circuit would decrease the energy. Due to the nonvolatile hysteretic function, the energy change for bit flip in this network is thresholded, which is different from the classic Hopfield network. It allows more stable states stored in the circuit, thus representing a highly compact and efficient solution for associative memory. Network dynamics (towards stable states) and their modulations by external voltages have been demonstrated in experiment by 3-neuron and 4-neuron circuits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resistive memory devices possess rich dynamics, including electrical, thermal, and structural effects1,2,3,4,5. By exploiting the switching dynamics or simply the programmable resistance attribute, resistive memory enables highly efficient computations, such as stateful logic6, temporal information processing7, and analog matrix computing8. Thanks to the nonvolatile switching and the crosspoint architecture, the resistive memory-based computations are promising to alleviate the von Neumann bottleneck and to provide massive parallelism9. For instance, crosspoint resistive memory arrays have been frequently employed to accelerate the matrix-vector multiplication (MVM) in many algorithms, among which neural networks have drawn the most attention10,11.

The attractor network is a kind of recurrent neural network (RNN) model working with interactive feedback, whereas the Hopfield network is a typical representative12. It has a strong connection with biological neural circuits and memory mechanisms and finds applications in associative memory and combinational optimization13,14,15. In the classic Hopfield network, a set of McCulloch-Pitts (MP) neurons are interconnected through a symmetric weight matrix. During the computing process, the neuronal states are updated (usually asynchronously) by performing a sequence of MVM operations and pointwise nonlinear functions12. Recently, there has been a series of works on the hardware implementation of the Hopfield network with crosspoint resistive memory arrays to accelerate the MVM operations16,17,18,19. In these works, the memory devices are used as static, programmable analog resistors to emulate highly simplified synapses. On the other hand, the neurons are usually simulated by traditional amplifier circuits, which, however, are considered inefficient in terms of area, time, and energy costs. In addition, as only the MVM operation is performed in this architecture, the algorithmic iterations are discretely conducted, which causes extra latency. In particular, the discrete iteration of analog computing requires analog-digital conversion interfaces, which incur a stubborn bottleneck that limits the computing efficiency.

Observe that a resistive memory device is not merely a programmable resistor, rather it has its own dynamics, which appear as thresholded, recyclable and nonvolatile switching behaviors20. The relationship between a column of resistive memory devices is described by the Kirchhoff’s current law (KCL), which contributes naturally a dot product operation. As a result, it is possible to sketch out an attractor network model, considering that: (1) resistive memory devices show a large ratio (typically 10−100) and fast speed (nanoseconds) of conductance change, thus the resistive switching (set and reset) can be viewed as a nonlinear activation21, (2) when applying voltages simultaneously to a column of resistive memory devices, switching of one device is conditional on the linear combination of other devices’ states described by KCL in the circuit, (3) the switching of one device changes the overall distribution of potentials in the circuit, which plays feedback to trigger further switching events, updating the state vector of the devices. This approach is an emergent result of a simple circuit consisting of passive resistive switching devices, which is in sharp contrast to the hardware mapping of the Hopfield network with resistive devices and active amplifiers.

As such, the resistive memory circuit could be an intrinsic attractor network where the device states (upon application of a set of voltages) evolve from an initial vector and eventually stabilize at some states after a sequence of state changes, which are attractors of the circuit. In this network, the weight parameters and, hence the state stability are determined and modulated by the applied voltages. Given the high compactness of resistive memory devices and the absence of active components, this approach should deliver high efficiency of attractor networks for relevant applications. In addition, because of the unique neuronal activation, the resistive memory network is prone to store more attractors than the Hopfield network, which is very beneficial to improving the storage capacity in associative memory.

Results

Emergent attractor network model

There are several resistive switching device concepts, including nonvolatile but bipolar or unipolar, and volatile devices22,23. Nonvolatile bipolar devices have drawn the most attention, due to their easy operation and high performance for storage-class memory and computing-in-memory applications. In a more general sense, there are several species of nonvolatile bipolar devices, including resistive random-access memory (RRAM), magnetic tunneling junction (MTJ), and ferroelectric tunneling junction (FTJ)24. Although they are characteristic of different physical mechanisms, their switching behaviors are similar. Fig. 1a shows the abstraction symbol of such devices, which is characteristic of a hysteretic nonlinear function.

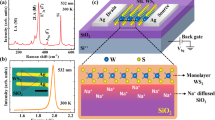

a Hysteretic neuron model of a nonvolatile resistive memory device. b Pulse-mode test results of the hysteretic nonlinear activation function. The programming pulse magnitude is swept forward from 0 to 0.8 V, backward to − 1.2 V, and again forward to 0 V, with a step of 0.01 V. The reading pulse is constantly 0.02 V. If there is a conductance change after a programming pulse, it will be set/reset to the initial state to be ready for the test of the next programming pulse. c The considered circuit is based on a column of resistive memory devices and a load resistor. Each resistive memory device is applied with a voltage through the word line (WL). The grounded resistor can be regarded as \({V}_{i}=\) 0. d An abstracted RNN model of the resistive memory circuit, with the weight definition.

The resistive memory device that we used is fabricated with a well-established Ta/HfO2-based RRAM technology25. Its structure and current-voltage (I-V) sweep result is shown in the SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S1. It is translated to a conductance-voltage (G-V) plot, showing a large hysteretic loop. The standard characteristics of the RRAM device were also measured, showing good retention and endurance performances26. In particular, the switching speed tests of the devices (SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S2) show that the switching time should be less than 100 ns. Fig. 1b shows the pulse-mode resistive switching results of the RRAM device, which is characteristic of a large hysteretic loop in the G-V plot, facilitating a neuron model inherent to a hysteretic nonlinear function. The pulse magnitude in the test is increased or decreased with a step size of 0.01 V, and its width is 500 ns which should be sufficient for allowing the device transitions in the circuit. After each pulse, a read operation with 0.02 V is performed. The results show that the device state would not change if the voltage across the device \({V}_{R}\) is in the range from \({V}_{{reset}}\) to \({V}_{{set}}\), staying in the nonvolatile high conductance state (HCS) or low conductance state (LCS). Otherwise, at a threshold \({V}_{{set}}\) (or \({V}_{{reset}}\)), the device is switched from LCS to HCS (or from HCS to LCS). Note that, while the set transition is abrupt with a distinct threshold (\({V}_{{set}}=0.6\) V), the reset process is more gradual, for which an average threshold (\({V}_{{reset}}=-1.1\) V) is extracted. The ratio of HCS/LCS is around 20, i.e., \({G}_{{HCS}}=800\) μS and \({G}_{{LCS}}=40\) μS, which testifies to their representations of logic states \(g=\) ‘1’ and \(g=\) ‘0’ with a large signal difference. The hysteretic behavior is summarized as Eq. 1, where \(g\left(t\right)\) and \(g\left(t+1\right)\) represents the device conductance state before and after the stimuli with a voltage pulse, respectively.

Equation 1 dictates a unique nonlinear activation function, where both set transition under positive voltage and reset transition under negative voltage are allowed, in contrast to conventional neuron models where usually a unidirectional transition is presented. In addition, the conductance state is nonvolatile, which provides a constant operator for multiplication with the applied voltage. Specifically, according to the KCL, the potential of the bit-line (BL) is the dot product result of the resistive state and the applied voltages (Fig. 1c). Combining the free dot product operation in the array, and the unique nonlinear function of RRAM devices, the circuit in Fig. 1c turns out to be an RNN, which is abstracted into the structure of Fig. 1d.

In this circuit, consider a network composed of \(N\) RRAM devices, which are connected together through the BL to a load resistor that is grounded (\({V}_{0}=0\)). Each RRAM device is applied with a voltage \({V}_{i}\), and the resistor’s conductance is \({G}_{0}\). As a result, the BL voltage \({V}_{{BL}}\) is expressed as \({V}_{{BL}}=\frac{{\sum}_{i}{V}_{i}{G}_{i}}{{\sum}_{i}{G}_{i}}\approx \frac{{\sum}_{i}{V}_{i}{g}_{i}}{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}\) \(\left(i=0,\,1,\,2,\,\ldots,\,N\right)\), where \(i=0\) represents the load resistor \({G}_{i}\) and \({g}_{i}\) \(\left(i\ne 0\right)\) are the conductance and logic state of the \(i\)-th neuron, respectively. The voltage across the \(j\)-th neuron \({V}_{{Rj}}\) is \({V}_{{Rj}}={V}_{j}-{V}_{{BL}}={V}_{j}\cdot \frac{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}-\frac{{\sum}_{i}{V}_{i}{g}_{i}}{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}=\frac{{\sum}_{i}{V}_{j}{g}_{i}}{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}-\frac{{\sum}_{i}{V}_{i}{g}_{i}}{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}=\frac{{\sum}_{i}\left({V}_{j}-{V}_{i}\right){g}_{i}}{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}\), which would modify the neuron state according to the hysteretic nonlinear function. The equation of \({V}_{{Rj}}\) can be formulated into \({V}_{{Rj}}={\sum}_{i}{w}_{{ji}}{g}_{i}\), where the conductance state \({g}_{i}\) is the input and \({w}_{{ji}}=\frac{{V}_{j}-{V}_{i}}{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}\) dictates the synaptic weight. For a network, the weighing matrix is given by

where \({{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}\) is a column vector composed of the applied voltages. It also implies that the weights are related to the instant conductance states of all neurons.

The circuit in Fig. 1c has been proven to be a neural network, which is featured by a hysteretic nonlinear function in Eq. 1 and an anti-symmetric weight matrix in Eq. 2. Since every neuron acts simultaneously as input and output, and the synaptic weights are dictated by the applied voltages, it is a kind of RNN, where the network dynamics should evolve until an equilibrium state. Intuitively, the switching of one RRAM device changes the voltage distribution in the circuit. The updated voltages across the neurons may be higher than \({V}_{{set}}\) or lower than \({V}_{{reset}}\), which acts as feedback to trigger another switching event, thus updating the state of the network. Eventually, the network stabilizes at an attractor state where the voltage drops are \( > {V}_{{reset}}\) for neurons at state ‘1’, or \( < {V}_{{set}}\) for neurons at state ‘0’. To this end, the classic Hopfield network is a good reference for studying this emergent attractor network12. Accordingly, we define an energy function as follows

where \(\overline{{g}_{j}}\) is the complement of \({g}_{j}\) subject to \({g}_{j}+\overline{{g}_{j}}=1\). \({T}_{j}\) represents the threshold which is related to \({g}_{j}\). If \({g}_{j}=0\), \({T}_{j}\) is \({V}_{{set}}\), otherwise \({T}_{j}\) is \({V}_{{reset}}\). \(j\ne 0\) implies only the energies of neurons are considered, excluding the load resistor. Each term in the summation of \(E\) is the energy of a neuron that measures its stability: if it is negative (thus contributing to a lower \(E\)), the neuron is stable (at state ‘1’ or ‘0’). Otherwise, the neuron is unstable and switches to the complementary state. If all the neurons are stable, the network reaches an attractor state and should have a sufficiently low \(E\). For a given set of voltages, the network weights are determined at each moment, and hence the attractor states and the transition trajectory of unstable states are determined. By substituting the weight formula of Eq. 2 in Eq. 3, the energy function turns out to be

where \({N}_{{g}_{i}=0}\) and \({N}_{{g}_{i}=1}\) indicate the number of neurons with conductance \(g=0\) or \(g=1\), respectively. The details of obtaining this equation are elaborated in SI Appendix, Text S1. As a special case, if \({V}_{{set}}=-{V}_{{reset}}\), Eq. 4 degrades as \(E={\sum}_{j}{V}_{j}-N{V}_{{set}}-\left(N+2{g}_{0}\right){V}_{{BL}}\), it suggests that \({V}_{{BL}}\) becomes the only variable controlling the network energy for a given set of voltages. Equation 4 relates the implicit energy of the network to an observable variable of the circuit, namely the BL voltage \({V}_{{BL}}\), which provides an aperture for monitoring the network energy in the experiment.

In an attractor network, every state transition of a neuron should decrease the network energy, which is valid for this emergent network. This can be explained with the help of the equivalence between the energy function and \({V}_{{BL}}\). If a certain device changes from ‘1’ to ‘0’, it means that the voltage applied to it is lower than \({V}_{{BL}}\) to cause the reset transition, then the resulting disconnection of this device contributes to the rise of \({V}_{{BL}}\), namely decreasing the energy; conversely, if a certain device changes from ‘0’ to ‘1’, it indicates that the voltage applied to it is higher than \({V}_{{BL}}\) to cause the set transition, then the resulting connection by this device contributes again to the rise of \({V}_{{BL}}\), namely decreasing the energy. To study the convergence behavior of the attractor network model, the energy change of the network is calculated for a 1-bit flip where the state of one neuron is flipped. It turns out that while every switching event decreases the network energy, a 1-bit flip only occurs when the energy change is sufficiently large. In the case of transition from ‘1’ to ‘0’, the condition in Eq. 5 must be met.

where \({g}_{i}^{{\prime} }\) represents the conductance state of the neuron after the switching. In this case, there is \({\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}^{{\prime} }={\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}-1\). Note that \({V}_{{reset}}\) is a negative value. Similarly, for the transition from ‘0’ to ‘1’, the condition for the transition to occur is Eq. 6.

In this case, there is \({\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}^{{\prime} }={\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}+1\). Again, if there is \({V}_{{set}}=-{V}_{{reset}}\), Eqs. 5 and 6 are unified, namely \(\varDelta E\le -\left(N+{2g}_{0}\right)\frac{{V}_{{set}}}{{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}^{{\prime} }}\), regardless of the specific type of transition. We provide the details of obtaining these two inequations in the SI Appendix, Supplementary Text S2. Therefore, during the network evolution, only if the energy difference between two neighboring states (with a Hamming distance of 1) satisfies Eqs. 5 or 6, the network continues to transit, otherwise it becomes convergent.

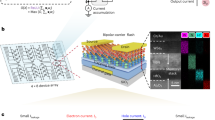

Such a principle is fundamentally different from the classic Hopfield network, where a transition between two neighboring states occurs only if there exists an energy difference, namely \(\varDelta E < 0\)27. The comparison between the two attractor network models regarding the requirement on energy change of 1-bit flip is schematically illustrated in Fig. 2a. Due to the proven energy difference threshold in Eqs. 5 and 6, the emergent attractor network may enable more attractor states, thus enhancing the storage capacity. Though a state may own a higher energy than its neighboring states, it could also be stable due to the threshold limitations, contributing an attractor state that is not favored in the Hopfield network.

In Fig. 2b, we summarize the differences between the resistive memory network and the Hopfield network. In the latter model, the MP neuron is used, which is a unidirectional and volatile model. As a result, the storage capacity of attractors is very limited, scaling only linearly with the number of neurons, asymptotically ~ 0.14 N, which suggests only a small number of vector states can be simultaneously memorized by the network28. Although there have been several efforts to increase the storage capacity by using a different nonlinear activation function or providing a different weight configuration29,30, they are at the algorithmic level and the hardware implementation remains unexplored. By contrast, a resistive memory device is a bidirectional and nonvolatile neuron, which enables more (e.g., a fraction of 2 N) stable states to be stored in the circuit. The hardware implementation of the Hopfield network requires a dedicated circuit design by using expensive amplifier circuits as neurons, a programmable resistive device as a synapse, and configuring feedback loops or running discrete iterations, which result in a larger circuit footprint and complicated operations16,31. In addition, the resistor synapses usually demand a customized writing circuit for programming analog conductance states. The emergent attractor network is inherent in a simple resistive memory circuit, and the feedback is implemented in continuous time by the underlying circuit physics, which seamlessly accelerates the convergence of the attractor dynamics. Nevertheless, digital-to-analog converters (DACs) are needed to provide analog voltages to define the weight matrix.

Experimental demonstrations

To demonstrate the emergent attractor network model, several sets of voltages were randomly generated and tested to showcase the network with the desired number of attractors. We first investigated the attractor network model for a given set of voltages \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{1}{{{\boldsymbol{=}}}}\) [− 1.2; − 0.2; 1.2] V, and performed circuit experiments with a column of Ta/HfO2 RRAM devices. The energy landscape of this 3-neuron network has been calculated and is shown in Fig. 3a. The transition trajectory has also been indicated by calculating the energy difference and judging whether it satisfies the conditions in Eqs. 5 or 6. Specifically, the transition from ‘100’ to ‘101’ is possible, as the energy difference is 3.5 V, greater than the required threshold (which is 1.5 V in this specific case), however, the transition from ‘100’ to ‘000’ or ‘110’ is impossible, although the latter two have lower energies than ‘100’. Similarly, the transition from ‘011’ to ‘001’ is forbidden, as the energy difference is 0.83 V, less than the required threshold (which is 2.25 V), thus contributing one more attractor in the network. Eventually, there are two attractors (‘001’ and ‘011’) for this combination of applied voltages, each of which attracts three other state vectors through 1 or 2 transitions that define their own attractor basins. The number of attractor states can be tuned by modifying the weight matrix through the applied voltages. In Fig. 3b, we record the numbers of stable states upon continuously changing the applied voltages proportional to \({{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{=}}}}\alpha {{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{1}\) (\(\alpha \, > \, 0\)). The results show that the number of stable states can be continuously tuned from 2 N to 1. The case of two attractors persists in a large range in the spectrum, indicating a high robustness of this configuration for pattern storage. Note that, in cases where there are many stable states (up to 2 N), some of them are isolated states, namely while they are stable not to transit, they also do not attract other states. In such cases, we prefer only to call it a stable state rather than an attractor state. Nevertheless, the wide range of tunability of the number of stable states offers an exponentially large space for designing and optimizing the attractors and their dynamics of this network model.

a Energy landscape and transition trajectory of a 3-neuron network that is applied with voltages \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{1}}}}}=\) [− 1.2; − 0.2; 1.2] V. The red boxes (‘001’ and ’011’) represent the stable states, each of which attracts three other state vectors. b Dependence of the number of stable states on the applied voltage amplitudes. The applied voltages are \({{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}=\alpha {{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{1}}}}}\), where \(\alpha\) is increased from 0 to 2. c State transition dynamics of the 3-neuron circuit upon the application of \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{1}}}}}\), which are monitored in real-time through \({V}_{{BL}}\) (middle panel) in the circuit. The turning points that indicate transitions are marked by red arrows. The middle panel is accompanied by two panels (upper and lower) that show the voltage drop across each device before and after the pulse stimulus. The conductance values in the top and bottom panels represent the initial and final states, respectively. The shaded areas represent the ranges of HCS and LCS, which present a sufficient margin to distinguish the two states in all 8 cases.

The attractor dynamics of the 3-neuron network upon applying voltages of \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{1}\) have been demonstrated in the experiment. Fig. 3c shows the results of all 8 cases, including the initial conductance states of 3 neurons, the real-time monitored \({V}_{{BL}}\) curve upon the application of voltage pulses \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{1}\), and the stabilized conductance states after applying the pulses. Every time a transition happens, the network energy should substantially decrease, and the \({V}_{{BL}}\) in sight should increase instantaneously, appearing as a turning point in the curve. For the two states ‘001’ and ‘011’, they have no transitions and correspond to two attractors. ‘000’, ‘010’, ‘101’ and ‘111’ each undergoes one transition, while ‘100’ and ‘110’ each undergoes two transitions. These results are exactly the expected ones in Fig. 3a, thus precisely validating the emergent attractor network in the resistive switching circuit. In some curves, the turning points may be vague, which is masked by the parasitic BL capacitance effect. In spite of the non-ideal issues including resistive memory conductance variations and gradual reset effect, the resulting states 1 and 0 are clearly distinguishable with a sufficient readout margin. It would be interesting to note that the weight matrix would change during the transitions, as it depends on both the applied voltages and the device states. We have visualized it for the ‘110’ and ‘100’ cases, and the experimental and theoretical results are shown in the SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S3.

Upon applying different combinations of voltages, different patterns of stable and unstable states are produced. Generally, large voltages are prone to reduce the number of attractors. We have experimentally tested two more cases, namely \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{2}{{{\boldsymbol{=}}}}\) [− 1.0; 0.4; − 0.6] V and \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{3}{{{\boldsymbol{=}}}}\) [− 1.0; − 1.6; 1.6] V. Their energy landscapes, voltage-dependence of the number of stable states, and the experimental validations are shown in SI Appendix, Supplementary Figs. S4, S5. In this case of \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{2}\), there are five stable states, and each of the three unstable states is attracted by a stable state upon the application of voltages, and the remaining two stable states are isolated. In the case of \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{3}\), there being only one attractor, all the unstable states will collapse to it through a chain of transitions (up to 3 transitions). All of these network evolution processes have been successfully monitored in the experiment, thanks to the convenient window provided by the circuit variable \({V}_{{BL}}\).

With more neurons in the model, the number of state vectors increases exponentially, and thus, more attractors would emerge. In experiment, we have tested a 4-neuron circuit, which is applied with a combination of voltages \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{4}=\) [0.4; − 1.2; 0.8; 0.8] V. It turns out that there are up to six stable states in this attractor network, namely ‘0001’, ‘0010’, ‘0011’, ‘1001’, ‘1010’, and ‘1011’, as shown in Fig. 4a. Such a capacity volume should not be achievable in the classic Hopfield network, thus demonstrating unambiguously the large storage capacity of the resistive memory network. The experimental results of network transitions for each initial state are summarized in the SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S6. The voltage-dependent number of stable states is shown in SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S7. Figure 4a shows the attractor map in a 4-dimensional graph to reveal the transition trajectory towards the attractors.

a Attractor map of the 4-neuron network applied with voltages \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{4}}}}}=\) [0.4; − 1.2; 0.8; 0.8] V. The red dots represent attractor states, and the red arrows indicate the transition paths. In associative memory application, the attractors ‘0001’, ‘0010’, and ‘0011’ are interpreted as cattle, deer, and horses in the daytime, respectively. ‘1001’, ‘1010’, and ‘1011’ are interpreted as the three animals at nighttime. A transition path represents a recalling process of an animal from a given initial vague pattern. b Map of state transition probabilities with consideration of \({V}_{{set}}\), \({V}_{{reset}}\), \({G}_{{HCS}}\) and \({G}_{{LCS}}\) distributions. Every element in the matrix is the probability of an initial state (vertical) transiting to a final state (horizontal). The experimental results are marked by red boxes, which correspond to the transition with the highest probability for most initial states.

Attractor networks have been frequently used for associative memory applications, where the memorized items are represented by attractor states, and the network would recall a memorized item upon providing a similar pattern that contains the same features in the initial state16,32. In Fig. 4a, the six attractors have been interpreted as associative memory recalling three kinds of animals (e.g., cattle, deer, and horse) in two types of backgrounds (e.g., daytime and nighttime). The large storage capacity of the emergent attractor network is very beneficial to this application to memorize more items and scenarios. Specifically, the first bit is used to encode the background, and the other three bits are used to represent the recognition of the animals, namely ‘0001’, ‘0010’, and ‘0011’ (or ‘1001’, ‘1010’ and ‘1011’) correspond to cattle, deer, and horse at daytime (or nighttime), respectively. The ten unstable states are incomplete patterns, each of which will collapse to one of the six memorized items through a recalling process. For instance, ‘0100’ represents a vague pattern with a heavy shadow. With some part of the shadow removed, the pattern is translated into ‘0101’ or ‘0110’, then progressively ‘0111’, which gradually approaches a horse pattern with increasing similarity. Finally, the state stabilizes at ‘0011’, which represents a correct memory of the horse, which shows a clear, distinct feature (e.g., no horns) from the other two animals in the daytime (‘0001’ and ‘0010’). In the case of nighttime, as the background is much noisy, the recalling processes of the three animals may be different from the daytime cases. For the given initial state ‘1100’ that represents a very vague pattern, a horse might be recalled as in daytime. Also, a cattle (‘1001’) might be recalled as through the intermediate state ‘1101’, or as a deer (’1010’) through the intermediate state ‘1110’.

Discussion

The emergent attractor network works with the physical computation of the dot product by KCL, where the two operands are conductance and voltage, as well as the hysteretic set/reset transitions. While the applied voltages may be provided by precise digital-to-analog converters and device parameters \({G}_{{LCS}}\), \({G}_{{HCS}}\), \({V}_{{set}}\) and \({V}_{{re}{set}}\) are inherently stochastic. To investigate the impact of variations of these parameters on the network characteristics (including the number of stable states and transition paths), we have performed sufficient device measurements to collect their statistics. By characterizing 14000 cycles of direct current (DC) I-V sweeps, the \({V}_{{set}}\) and \({V}_{{re}{set}}\) of each cycle are extracted, and their statistics are shown in SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S8. Note that the test parameters in the DC mode have been explored so that the mean values of \({V}_{{set}}\) and \({V}_{{re}{set}}\) are close to the results in the pulse mode. Both \({V}_{{set}}\) and \({V}_{{re}{set}}\) show normal distributions with their own mean values and standard deviations, namely \({V}_{{set}}=\) \(N\)(0.63, 0.14) V and \({V}_{{re}{set}}=\) \(N\)(− 1.12, 0.21) V. As shown in the SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S9, the statistics of \({G}_{{LCS}}\) and \({G}_{{HCS}}\) also follow normal distributions, subject to \({G}_{{LCS}}=\) \(N\)(65.5, 18.6) μS and \({G}_{{HCS}}=\) \(N\)(1082.9, 54.7) μS. Based on these results, we have carried out comprehensive evaluations of their impacts on the 4-neuron network applied with voltages \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{4}\).

In Eq. 4, the network energy is related to both threshold voltages (\({V}_{{set}}\) and \({V}_{{re}{set}}\)) and \({V}_{{BL}}\), the latter of which, in turn, is determined by the conductance states of neuron devices. Given that \({V}_{{set}}\), \({V}_{{re}{set}}\), \({G}_{{LCS}}\) and \({G}_{{HCS}}\) follow normal distributions, the network energy becomes rather a distribution function instead of a constant value. For the 4-neuron network applied with \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{4}\), the energies calculated for each state vector are summarized in the SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S10. Due to the variations of energies, all the transitions between state vectors become probabilistic, and the limitation on the transitions between certain states may be broken (SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S10). Fig. 4b shows the probabilities of the final states for a given initial state after considering the energy distributions, where the vertical/horizontal axis dictates the initial/final state, and the corresponding experimental case is marked with a red box. Such simulations have been extended to larger networks, including 6-neuron and 8-neuron networks, and the results of the energy function and state transition probability (SI Appendix, Supplementary Figs. S11, S12) show similar trends as the 4-neuron network. In such realistic cases, the emergent attractor network turns out to be similar to the Boltzmann machine concept33, which is a probabilistic version of the classic Hopfield network. In particular, the switching with probabilistic thresholds (\({V}_{{set}}\) and \({V}_{{re}{set}}\)) depicts very closely the behavior of the Boltzmann machine.

Specifically, the transitions of unstable states become more diverse with a distribution of probability. In the deterministic situation, state ‘0100’ will not transit to ‘1100’ due to the requirement of energy change threshold (even though state ‘1100’ has a lower energy). In the probabilistic situation, however, there is a probability of 36% that this transition may happen. Some deterministic attractor states also may cascade to a lower-energy state, such as the transitions from ‘0001’ or ‘0010’ to ‘0011’ with a probability of 10%, and those from ‘1001’ or ‘1010’ to ‘1011’ with a probability of 9%. Only the two attractors with the lowest energy (‘0011’ and ‘1011’) are deterministically stable. Such behaviors may be utilized to explore the application of resistive memory networks to probabilistic computing tasks.

Because of the disturbance of probabilistic switching that breaks out of the constraint on state transition, the number of attractors is also affected. Supplementary Figs. S13and S14 in the SI Appendix show the impact of each factor including \({V}_{{set}}\), \({V}_{{re}{set}}\), \({G}_{{HCS}}\) and \({G}_{{LCS}}\) analyzed one by one, for the given voltages \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{4}\). The first observation is that the impact of threshold voltage on the results is substantially greater than that of conductance. In particular, the \({V}_{{set}}\) distribution has the highest impact, which should be ascribed to the fact that, in this specific case, states with more bits of ‘0’ are prone to be unstable and thus experience more set transitions. Meanwhile, the impact of \({G}_{{LCS}}\) distribution is almost ignorable, due to its small conductance value involved in the computation. By including distributions of all parameters in the simulation, the resulting number of attractors also presents a normal distribution (SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S15). We note the load resistor with conductance \({G}_{0}\) may also have an effect on the network behaviors (SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S16), although it should be much more controllable than the stochastic resistive memory devices.

In the model, the LCS and HCS of resistive memory have been taken as logical 0 and 1 to participate in the deduction of equations, which should be an idealized situation. In practice, the conductance of LCS is absolutely not 0, and a finite ratio \(\varDelta\) = \({G}_{{LCS}}\)/\({G}_{{HCS}}\) of should be considered. We have also investigated the impact of this factor on the network behaviors, through both numerical simulation (SI Appendix, Supplementary Fig. S17) and theoretical analysis (SI Appendix, Supplementary Text S3). The results show that the ratio \(\varDelta\) does not cause a substantial change to the evolvement of the number of stable states with increasing voltages, demonstrating that the model’s moderate sensitivity to it. In addition, we have also considered the situation when the network is scaled up. It is observed from Supplementary Fig. S18 in the SI Appendix that as the network scales up, the change of the curve becomes even more subtle, undoubtedly supporting the scalability of the model with non-ideal conductance.

Regarding the power consumption, as only one RRAM device switches each time (sequentially) in the circuit, the switching current should not be accumulated. It turns out to be like a chain of automatic memory writing/erase operations and should not cause line destruction and drive circuitry overhead. In between two switching events, the accumulated current on the bit line is given by \({I}_{{BL}}=\frac{{\sum}_{i}{V}_{i}{g}_{i}}{{g}_{0}{\sum}_{i}{g}_{i}}\), which is a multiply-and-average (MAV) operation. The sum of conductances in the denominator term should relax the accumulated currents. This is in contrast to the common dot product operation, where more high-conductance devices would contribute to a higher accumulated current, but here the current would be averaged out by the conductance sum. The relaxed current on the bit line should also help alleviate the IR drop issue caused by the line resistance, for which we have carried out circuit simulations of the 8-neuron network. The results show that even when all the devices are in state ‘1’ (HCS), the voltage drop caused by line resistance is merely in the range of mV, which is negligible compared to the threshold voltages (\({V}_{{set}}\) and \({V}_{{reset}}\)) and should have a very limited impact on the circuit dynamics. In addition, although the endurance of RRAM devices is limited with respect to conventional volatile memories34, i.e., SRAM and DRAM, the recalling of attractor states through a sequence of switching events is essentially a kind of inference process in the attractor network. Different from the conventional memory application where high endurance is essential, the requirement on the endurance performance of RRAM devices should be much weaker for inference, which is also true for other neural networks for the same application.

In this work, we theoretically and experimentally demonstrate that a circuit composed of a column of resistive switching devices is inherently an attractor network. A nonvolatile resistive memory device is an artificial neuron that provides a hysteretic nonlinear activation function. The recursion in the network is enabled by the interaction between the devices, which is formulated as an anti-symmetric weight matrix dictated by the applied voltages. Such an approach facilitates associative memory applications with less hardware cost, sharply opposite to the conventional implementation of the Hopfield network where resistive devices are used as synapses and voltages represent neuronal input/output. We also elaborate an energy function for this network and the convergence analysis therein, by referring to the classic Hopfield network. The unique activation function and synaptic weights endow the resistive memory network with a high storage capacity, which can be tuned in the exponential range. By considering device variations, the network turns into a probabilistic model, which is intriguing and promising for relevant applications. The concept should be extended to other device species, such as unipolar or threshold-switching devices, thus developing or inspiring new attractor network models and hardware solutions.

Methods

Device fabrication

The RRAM devices were fabricated on a SiO2/Si substrate. First, the bottom electrode, which comprises a 5 nm Ti adhesion layer and a 40 nm Pt layer, was deposited through magnetron sputtering and patterned using photolithography and a lift-off process. The dielectric layer is 5 nm HfO2, which was prepared using atomic layer deposition. Finally, the top electrode, consisting of 30 nm Ta and 40 nm Pt, was deposited and patterned.

Experimental measurements

The electrical characteristics of RRAM devices were acquired using a Keysight B1500A Semiconductor Parameter Analyzer. In the experiment, the circuit was established by mounting the packaged RRAM array onto a customized PCB. Pulse voltages were supplied by the Tabor Electronics Model WW5064 Four-Channel Waveform Generator. In addition, signal capture was performed with the RIGOL MSO8104 Four-Channel Digital Oscilloscope.

Data availability

All data supporting this study and its findings are available within the article, its Supplementary Information and associated files. All source data for this study are available through the Zenodo database under accession code [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13335508].

Code availability

The codes supporting the findings of this study are available through the Zenodo database under the accession code [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13335508].

References

Ielmini, D. Resistive switching memories based on metal oxides: mechanisms, reliability and scaling. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 31, 063002 (2016).

Pan, F., Gao, S., Chen, C., Song, C. & Zeng, F. Recent progress in resistive random access memories: Materials, switching mechanisms, and performance. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 83, 1–59 (2014).

Noé, P., Vallée, C., Hippert, F., Fillot, F. & Raty, J.-Y. Phase-change materials for non-volatile memory devices: from technological challenges to materials science issues. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 33, 013002 (2017).

Slesazeck, S. & Mikolajick, T. Nanoscale resistive switching memory devices: a review. Nanotechnology 30, 352003 (2019).

Kim, S., Choi, S. & Lu, W. Comprehensive physical model of dynamic resistive switching in an oxide memristor. ACS Nano 8, 2369–2376 (2014).

Borghetti, J. et al. Memristive’ switches enable ‘stateful’ logic operations via material implication. Nature 464, 873–876 (2010).

Prezioso, M. et al. Spike-timing-dependent plasticity learning of coincidence detection with passively integrated memristive circuits. Nat. Commun. 9, 5311 (2018).

Sun, Z. & Ielmini, D. Invited tutorial: Analog matrix computing with crosspoint resistive memory arrays. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Express Briefs 69, 3024–3029 (2022).

Sun, Z. et al. A full spectrum of computing-in-memory technologies. Nat. Electron. 6, 823–835 (2023).

Wan, W. et al. A compute-in-memory chip based on resistive random-access memory. Nature 608, 504–512 (2022).

Ambrogio, S. et al. An analog-AI chip for energy-efficient speech recognition and transcription. Nature 620, 768–775 (2023).

Hopfield, J. J. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 2554–2558 (1982).

Hopfield, J. J. Neurons with graded response have collective computational properties like those of two-state neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 3088–3092 (1984).

Hopfield, J. J. & Tank, D. W. Neural’ computation of decisions in optimization problems. Biol. Cybern. 52, 141–152 (1985).

Hopfield, J. J. & Tank, D. W. Computing with neural circuits: a model. Science 233, 625–633 (1986).

Hu, S. G. et al. Associative memory realized by a reconfigurable memristive Hopfield neural network. Nat. Commun. 6, 7522 (2015).

Cai, F. et al. Power-efficient combinatorial optimization using intrinsic noise in memristor Hopfield neural networks. Nat. Electron. 3, 409–418 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Associative memory for image recovery with a high‐performance memristor array. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900155 (2019).

Yang, K. et al. Transiently chaotic simulated annealing based on intrinsic nonlinearity of memristors for efficient solution of optimization problems. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba9901 (2020).

Mannocci, P., Farronato, M., Lepri, N. & Cattaneo, L. In-memory computing with emerging memory devices: Status and outlook. APL Mach. Learn. 1, 010902 (2023).

Sun, Z., Ambrosi, E., Bricalli, A. & Ielmini, D. Logic computing with stateful neural networks of resistive switches. Adv. Mater. 30, e1802554 (2018).

Waser, R., Dittmann, R., Staikov, G. & Szot, K. Redox-based resistive switching memories – nanoionic mechanisms, prospects, and challenges. Adv. Mater. 21, 2632–2663 (2009).

Li, H. et al. Memristive crossbar arrays for storage and computing applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 3, 2100017 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Resistive switching materials for information processing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 173–195 (2020).

Jiang, H., Li, C. & Xia, Q. Ta/HfO2 memristors: from device physics to neural networks. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 61, SM0802 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. In-memory analog solution of compressed sensing recovery in one step. Sci. Adv. 9, eadj2908 (2023).

Rojas, R. The backpropagation algorithm. Neural Networks: a Systematic Introduction, 149–182 (1996).

Abu-Mostafa, Y. & St. Jacques, J. Information capacity of the Hopfield model. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 31, 461–464 (1985).

Krotov, D. & Hopfield, J. J. Dense associative memory for pattern recognition. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 29 (2016).

Demircigil, M., Heusel, J., Löwe, M., Upgang, S. & Vermet, F. On a model of associative memory with huge storage capacity. J. Stat. Phys. 168, 288–299 (2017).

Yan, M. et al. Ferroelectric synaptic transistor network for associative memory. Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 2001276 (2021).

Yan, X. et al. Moiré synaptic transistor with room-temperature neuromorphic functionality. Nature 624, 551–556 (2023).

Ackley, D. H., Hinton, G. E. & Sejnowski, T. J. A learning algorithm for Boltzmann machines. Cogn. Sci. 9, 147–169 (1985).

Zahoor, F., Azni Zulkifli, T. Z. & Khanday, F. A. Resistive random access memory (RRAM): An overview of materials, switching mechanism, performance, multilevel cell (mlc) storage, modeling, and applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 15, 90 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work has received funding from the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant 2020YFB2206001 (Z.S.) and 2023YFB4502200 (Y.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62004002 (Z.S.), Grant 92064004 (Y.Y. and Z.S.), 61927901 (Y.Y. and Z.S.), and 61925401 (Y.Y.), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation under Grant L234026 (Y.Y.), and the 111 Project under Grant B18001 (Y.Y. and Z.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.S. developed the theoretical framework of the attractor network model of the resistive switching circuit. Y.L. characterized the RRAM devices, performed the circuit experiments, and carried out the network simulations. S.W. fabricated the devices, and helped with the experiments. K.Y. and Y.Y. participated in the circuit analysis and application demonstration. Y.L. and Z.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. Z.S. supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhongrui Wang, Piergiulio Mannocci, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Wang, S., Yang, K. et al. An emergent attractor network in a passive resistive switching circuit. Nat Commun 15, 7683 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52132-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52132-9