Abstract

Simultaneous achievement of lightweight, ultrahigh strength, large fracture strain, and high damping capability is challenging because some of these mechanical properties are mutually exclusive. Here, we utilize self-assembled polymeric carbon precursor materials in combination with scalable nano-imprinting lithography to produce nanoporous carbon nanopillars. Remarkably, nanoporosity induced via sacrificial template significantly reduces the mass density of amorphous carbon to 0.66 ~ 0.82 g cm−3 while the yield and fracture strengths of nanoporous carbon nanopillars are higher than those of most engineering materials with the similar mass density. Moreover, these nanopillars display both elastic and plastic behavior with large fracture strain. A reversible part of the sp2-to-sp3 transition produces large elastic strain and a high loss factor (up to 0.033) comparable to Ni-Ti shape memory alloys. The irreversible part of the sp2-to-sp3 transition enables plastic deformation, leading to a large fracture strain of up to 35%. These findings are substantiated using simulation studies. None of the existing structural materials exhibit a comparable combination of mass density, strength, deformability, and damping capability. Hence, the results of this study illustrate the potential of both dense and nanoporous amorphous carbon materials as superior structural nanomaterials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoporous materials are structurally classified as materials having pore sizes typically less than 100 nm, whose properties are governed by matrix material as well as shape, size, and distribution of pores1. Their high surface area and the tunability of pore topologies facilitate unique physical and chemical properties, making them suitable for various applications such as ion exchange, separation, sensors, CO2 capture and storage, water purification, catalysis, renewable energy, drug delivery, and tissue engineering2. In addition, their excellent mechanical properties with the combination of lightweight and high strength render them a potential candidate for future structural applications in aerospace, automobile, and military engineering3.

It is difficult to achieve lightweight and high strength simultaneously using classic microstructural control of bulk monolithic materials because the strength of materials is generally proportional to their mass density4. For instance, it is not easy to create a lightweight polymer material that possesses the strength of heavy steel. Interestingly, the creation of nanoporous structures could enable us to reduce the mass density within the same class of materials without the significant sacrifice of strength because nanoscale ligaments can impart ultrahigh strength due to the mechanical size effects, so-called “Smaller is Stronger” behavior5,6,7,8,9. Recent nanomechanics studies have demonstrated that a material exhibits a significant enhancement of strength if its dimension approaches the nanoscale. Nanopillars, nanowires, and nanoparticles often exhibit the strength 20–100 times higher than their bulk counterparts because the absence of flaws and defects in such a small volume can improve strength substantially5. It is expected that the nanoscale ligaments in a nanoporous structure could also exhibit ultrahigh strength through the mechanical size effect, leading to the high effective strength of nanoporous materials.

Nanoporous materials have been successfully fabricated by a variety of methods, including dealloying, soft/hard templating, microwave irradiation, additive manufacturing, ion-beam processing, and laser processing2. Specifically, nanoporous metals and ceramics are typically fabricated using selective chemical removal of one phase from two-phase alloy mixtures10 and hard templating with silica colloidal crystals11, respectively. Nanoporous metals, ceramics, and their mixtures exhibit reasonably high strength, 10–200 MPa, with their high strength-to-weight ratio and a mass density of 1–10 g cm−3 12. Nevertheless, several factors still inhibit the desired improvement in mechanical properties of nanoporous materials: First, conventional fabrication methods of nanoporous metals or ceramics do not allow the fabrication of nanoporous structures with extremely thin ligament dimensions. Dealloying and templating methods usually limit the ligament thickness down to 50–100 nm2. To exploit the size affected strength more effectively, it is desirable to reduce the ligament thickness down below 50 nm, which would allow us to maximize the mechanical size effect. Interestingly, the size reduction has also been known to enhance the ductility due to the flaw tolerance effect at the nanoscale. Brittle-to-ductile transition has been observed in metallic glasses13, semiconductors14, quasicrystals15, and nanolattices16 when their structural length-scale lies in the regime of 100 nm or smaller. Thus, the reduction of thickness of ligaments could enable the creation of more ductile nanoporous structures. Second, metals and ceramics exhibit relatively low specific strength due to their heavy mass density. To achieve lightweight and ultrahigh strength simultaneously, it is critical to create nanoporous structures from high specific strength materials, such as carbonaceous materials17,18.

Recently, nanoporous amorphous carbon materials have been successfully fabricated in various ways, including sequential chemical dealloying, hard and soft templating2. These methods successfully produce ligaments with thicknesses much thinner than 50 nm. Most of these materials have been investigated to study the capacitance properties19, electrochemical properties20, and biocompatibility21. Moreover, their mechanical properties are also expected to be excellent, specifically strength and ductility, considering the high breaking strength of C–C bond and the mechanical size effect. Some studies have utilized two-photon laser lithography to produce pyrolytic carbon with various nanostructures including carbon nanopillars and nanolattices9,17,22. Especially, pyrolysis of 3D-printed nanocluster-based photoresist produces micro-/nano-structures of nanoporous amorphous carbon22. The mass density of these structures can be tuned by controlling the unit cell structure, the strut thickness, as well as the porosity. However, two-photon laser lithography is an expensive and very time-consuming technique9. Therefore, it is essential to develop nanoporous amorphous carbon with the precise control of porosity and structure length scale through an economically viable way. This will facilitate a systematic study of the mechanical properties of nanoporous amorphous carbon and draw comparison with other advanced structural materials through statistically reliable mechanical analysis.

In this work, therefore, we have developed lightweight nanoporous amorphous carbon nanopillars exhibiting ultrahigh strength, high deformability, and high damping-capability. Nanoporous nanopillar structures were derived by carbonization of the self-assembled nanocomposite of phenol-formaldehyde (PF) resin and bottlebrush block copolymers (BBCP) in combination with low cost and scalable nano-imprinting lithography (NIL). The use of BBCP enables precise control over porosity ranging from 0% to 59% with remarkably low shrinkage during carbonization (less than 20%). These produced specimens possess extremely fine and uniform porous structures with pore size of ~50 nm and the ligament thickness in the range of 20 nm or thinner. Our fully dense amorphous carbon nanopillars and nanoporous structures represent exceptional mechanical properties, including yield and fracture strengths higher than those of most engineering materials with the similar mass density, a large elastic strain (up to 13%), a large fracture strain (up to 35%), and high damping capability with the loss factor (up to 0.033). Due to the lightweight and ultrahigh strength, the specific strength and the modulus of resilience of our materials is higher than any other engineering materials within a similar range of mass density. Micromechanical tests, electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), Raman spectroscopy, and atomistic simulation revealed that reversible and irreversible portions of the sp2-to-sp3 transition and the nanoscale dimension of ligaments led to large elastic and fracture strains as well as high damping capability. Remarkably, none of the known structural materials achieves this unique combination of mechanical properties in terms of weight, elasticity, plasticity, and damping. Thus, this work demonstrates the preparation of next generation superior structural nanomaterials for aerospace, military, energy, biomedical, filtration, and catalyst applications.

Results

Fabrication of fully dense and nanoporous nanopillars

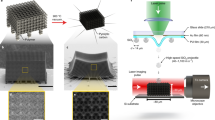

Nanopillars of fully dense amorphous carbon and their nanoporous structures were fabricated by spin-coating the film (~5 μm) of self-assembled BBCP and PF thin films followed by NIL and thermal annealing (Fig. 1a, b) (see also “Methods”). Nanopillars (~300 nm diameter and ~1 µm height) with the five different porosities (0, 40, 46, 51, and 59%) were prepared to obtain samples with different mass densities ranging from 0.66 to 1.6 g cm−3. The details of the porosity and density measurement are available in Supplementary Method 1. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images (Fig. 1c–e) show that fully dense and uniform nanoporous structures in nanopillars were created successfully. High-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) images of both fully dense and nanoporous carbon show the disordered atomic arrangement (Fig. 1f–h), confirming the formation of amorphous phase. The two halo rings in the selected area diffraction pattern (SADP) (marked by the white arrows in the inset of Fig. 1f, g) correspond to the interplanar spacing of ~1.15 Å and ~1.95 Å, which are typically observed from fully amorphous carbon structures23. Moreover, there is no noticeable difference in atomic arrangements of fully dense and nanoporous structure, and hence the mechanical properties of these nanopillars are expected to be solely governed by the difference in their porosity/porous structure. Note that the atomic arrangement of our specimens is different from the other commonly observed structure of crumbled graphite/graphene networks, which possess folded graphene layers in HRTEM images and several halo diffraction rings due to the higher degree of atomic ordering24,25,26. The different atomic arrangement of our nanopillars may result from the random orientation of the molecular chains of the PF carbon precursor and the carbonization temperature employed, which impedes the easy crystallization of carbon atoms19.

a Schematic diagram of nanopillar fabrication; b SEM image of nanopillar array; SEM images of nanopillar and surface structure of c fully dense amorphous carbon nanopillar, d 46% porosity nanopillar, and e 59% porosity nanopillar; HRTEM images of f the fully dense amorphous carbon and g the 59% porosity nanoporous carbon. The inset shows the SADP, which includes two halo rings (marked by the white arrows); h HRTEM image of the 59% porosity nanoporous carbon. Note that pore surface is atomically smooth.

It is worthwhile to note that NIL has a significant advantage over commonly used focused-ion-beam (FIB) milling. FIB milling requires a substantial amount of time to create a single nanopillar27,28 whereas a large number of nanopillars produced using NIL quickly and efficiently allows us to test several nanopillars and obtain statistically reliable mechanical properties. Additionally, self-assembled BBCP and PF resin composite as an ink for NIL enabled the formation of nanopillar with homogenous porous structure after carbonization (see “Method” section). This can be attributed to the relatively very small domain size (~50 nm) of the nanocomposite as compared to smallest dimension of pillar (~300 nm diameter), permitting the formation of uniform porous structure in nanopillar. Remarkably, the NIL process and developed ink were also utilized for imprinting various three-dimensional architecture with maintained porous structure demonstrating the versatility of this fabrication technique (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

In situ micromechanical characterization

In situ uniaxial compression tests (Fig. 2a–d) revealed a significantly large fracture strain from all nanopillars, comprised of substantial elastic recovery and plastic deformation (see also Supplementary Movie 1). A permanent height change was also observed when the test was stopped right before the fracture (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, we could not find any signature of local fracture in the nanoporous structures even after a substantial amount of plastic deformation, implying that the plastic strain is produced by mechanisms that cannot be easily observed by SEM. The mechanical loading was also stopped right after a significant displacement jump, which can be regarded as the initiation of fracture, and the SEM image shows that the fracture occurred via shear banding (Fig. 2c). Nanoindentation was also performed on the thin film area adjacent to nanopillars to measure Young’s moduli precisely. The obtained values matched well to that of data derived from micropillar experiments (Fig. 2d, e). We also found that there is negligible depth dependence in our Young’s modulus data, indicating that nanoindentation data are not influenced by sink-in or pile-up effects. Nanopillar compression and nanoindentation data of all specimens are available in Supplementary Figs. 3–6 and Supplementary Tables 2, 3. In general, the yield strength (\({{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{y}}}}\)), fracture strength (\({{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{f}}}}\)), and Young’s modulus (E) decreased as the porosity increased (Fig. 2e–f). The power law scaling relations29 \({{\boldsymbol{E}}} \sim {{{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}}^{{{\boldsymbol{-}}}{{\boldsymbol{m}}}}\) (the inset of Fig. 2e) and \({{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{f}}}} \sim {{{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}}^{{{\boldsymbol{-}}}{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}\) (the inset of Fig. 2f) with the relative density (\({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}\)) show \({{\boldsymbol{m}}}=\) 1.42 and \({{\boldsymbol{n}}}=\) 2.03, respectively. These results imply that the elastic deformation is the mixture of bending-dominant and stretching-dominant deformation while the fracture is close to bending-dominant fracture29. This can be attributed to the complex nanoporous structures which may have resulted in different mechanical responses to elasticity and fracture.

a SEM snapshots of microcompression test of 59% porosity nanoporous carbon nanopillar. \({{{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\bf{p}}}}\) represent plastic strain and \({{{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\bf{e}}}}\) represent elastic strain. (See also Supplementary Movie 1); SEM images of 59% porosity nanoporous carbon nanopillar b before and after plastic deformation, and c after shear fracture; d Representative engineering stress-strain curves; e Young’s modulus as a function of porosity. Error bars represent standard deviation of 64 tests. The inset shows the power law relation between Young’s modulus and relative density; f Fracture strength and yield strength as a function of porosity. Error bars represent standard deviation of 10 tests. The blue color line indicates the magnitude of the Suquet upper bound. The inset shows the power law relation between strength and relative density; g (left) fracture, elastic, and plastic strains as a function of porosity. (Right) fracture, elastic, and plastic strains as a function of pore size. These specimens have the 51% porosity, but different pore sizes: 21.8 ± 3.3 nm (small), 39.4 ± 4.0 nm (medium), and 79.4 ± 10.0 nm (large). Error bars represent standard deviation of 10 tests. The black arrows in both figures show the presence of transition in fracture strain.

Our mechanical data shows that the fracture and yield strengths of all specimens reached 50–75% of the Suquet upper bound (marked by the blue line in Fig. 2f), which is the most widely used value to approximate the theoretical topological strength limits of isotropic cellular solids30. The Suquet upper bound is defined as:

where \({{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{s}}}}\) is the yield strength of the corresponding constituent materials and \({{{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}}\) represents the relative density of the porous materials30. In practice, stress concentrations reduce their actual mechanical performance to around 20–25% of the Suquet upper bound31,32. With the presence of nanoporous structure, however, the yield strengths of our samples maintain the high fraction (50–75%) of the Suquet upper bound. This result indicates that the creation of additional free surface, which sometimes acts as a source of plastic deformation or fracture, does not play a significant role while the creation of thin ligaments seems to keep ultrahigh strength via the nanoscale size effect. It has been reported that nanoscale diamonds with ~100 nm in thickness show ultrahigh strength and significantly large fracture strain due to the absence of internal defects and smooth surface in their small volume7,33. The ligaments in our nanoporous amorphous carbon are around 20 nm, which is much thinner than these nanoscale diamonds. Thus, there is an even smaller chance of containing any critical flaws in ligaments of our nanoporous structures. The introduction of free surface seems to degrade the strength to some extent, so the nanoporous samples with the higher porosity (59%) exhibit strength more deviated from its Suquet upper bound, compared to the samples with the lower porosity. However, the HRTEM images depict the formation of the atomically smooth pore surfaces, confirming that the produced nanoporous carbon is free from any critical surface flaws. Therefore, the robust C–C covalent bonding and the absence of defects within nanoscale ligaments and on the pore surfaces are the main reasons for the ultrahigh strength, which does not drop below 20–25% of the Suquet upper bound regardless of the substantial increase in surface area. We also fabricated micropillars with 2 μm in diameter and 6 μm in height (~260 times larger volume) using FIB milling. We confirmed that all FIB-ed micropillars show nearly the same mechanical properties as nanoimprinted nanopillars (see also Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 4), affirming that the mechanical properties remain unchanged up to the micrometer scale. Thus, the sample dimension of our nanopillars is small enough not to contain any detrimental defects, such as abnormally large pores or cracks.

We also found the fracture strain exhibits an interesting transition with the porosity change (marked by black arrows in Fig. 2g). In general, the fracture strain of our samples decreases as the porosity increases. However, nanopillar with the highest porosity (59%) shows a higher fracture strain of 25 ± 0.11% than that of 18 ± 0.45% of the nanopillar with the porosity of 51%. These results were repeatable as indicated by the small error in data. This remarkable increase is primarily attributed to the increase in plastic strain because the elastic strain decreases as the porosity increases. In other words, the ductility of the material increases as the porosity of the sample rises from 51 to 59%. We also observed a similar transition when the pore size (21.8 ± 3.3 nm (small), 39.4 ± 4.0 nm (medium), and 79.4 ± 10.0 nm (large)) is varied while the porosity (51%) remains unchanged (Fig. 2g). As the pore size decreases, the ligament thickness also decreases (Fig. 1d, e). This implies that the transition of plastic strain is specifically being governed by the ligament thickness. Based on our mechanical data (Fig. 2g), the plastic strain increased when the average ligament thickness decreases to 11.3 nm for the sample with 59% porosity or 7.2 nm for the 51% porosity and small pore size sample (The average ligament thickness of all samples is available in Supplementary Table 5). This result indicates that if the average ligament thickness of amorphous carbon becomes approximately 10 nm or smaller, the plastic strain increases. Enhanced ductility (or plastic strain) has been frequently observed at the nanoscale. Metallic glasses13, semiconductors14, and quasicrystals15 are extremely brittle at bulk scale but showed significant improvement in plastic strain due to the flaw tolerance effect at the nanoscale when their dimensions become smaller than 100 nm. Also, some ceramic nanolattices, which could be considered as the highly ordered nanoporous structure, exhibited the improved plastic strain when the thickness of strut becomes smaller than 50–100 nm16,34,35. The ligament thickness of our highest porosity nanopillar is much thinner than 100 nm. Hence, based on the flaw tolerance at the nanoscale observed in other nanomaterials, our highest porosity nanopillar (or small pore size nanopillar) could also exhibit improved plastic strain. However, it is difficult to understand quantitatively how the critical thickness becomes ~10 nm. The critical thickness should depend on internal and external arrangements of carbon atoms, the geometry of ligaments, and the size effect on plasticity mechanism. Understanding the critical thickness requires additional theoretical study which will be investigated in our forthcoming work.

Mechanisms of elasticity, plasticity, and fracture

To thoroughly investigate the deformation mechanism, we studied deformation-induced changes in atomic arrangement/configuration of amorphous carbon. Here, we utilized fully dense carbon considering the fact that all nanoporous structures irrespective of their porosity are composed of same amorphous carbon as discussed in the previous section. The atomic scale structural change (sp2-to-sp3 transition) of a fully dense amorphous carbon nanopillar was analyzed using EELS, Raman spectroscopy, cyclic loading test, and atomistic simulations. Then, its implication for mechanical properties of nanoporous structures will be discussed in this section.

EELS analysis was conducted on the pillar at two different locations. The first location was the region compressed to approximately 35% strain, while the second location was the pillar base, which underwent a negligible amount of plasticity (Fig. 3a). Two-windows method36 was used to determine the fraction of sp2 bond by integrating the intensity of 1s-π* and 1s-σ* from 282–286 eV window and 288–298 eV window, respectively. The result shows that the sp2 fraction (~94%) of the compressed nanopillar is about 4% lower to the pillar base (~98%).

a EELS measurements of the fraction of sp2 bonded carbon atoms in nanopillar (left graph) and in base (right graph); b Raman spectroscopy data before and after compression; c Schematic diagram of energy barriers for elastic loading and unloading; d Engineering stress-strain curve of cyclic compression test. Black curves show the recoverable hysteresis deformation. Blue curves show the non-linear recovery after plastic deformation. Red broken lines show how the slope of unloading curve changes; e Simulated sp2/sp3 fraction of fully dense amorphous carbon. f Simulated stress-strain curve of fully dense amorphous carbon and the snapshots of microstructural evolution during loading and unloading (see also Supplementary Movie 3). Blue-colored and red-colored atoms represent sp2-bonded and sp3-bonded atoms, respectively. Red broken lines in the graph show how the slope of unloading curve changes.

Raman spectroscopy analysis was conducted before and after compressing identical nanopillars by ~35% in strain (Fig. 3b) to further explore the carbon microstructure changes. In the Raman spectra range of 800 cm−1 to 2000 cm−1, two characteristic peaks are typically observed for amorphous carbon materials. The D peak, centered at ~1380 cm−1, corresponds to the A1g breathing mode only in aromatic rings, while the G peak, centered at ~1560 cm−1, corresponds to the E2g stretching mode of sp2 atoms in both aromatic rings and olefinic chains37. The Raman spectra shows the increase in D peak intensity and the positive shift of G peak after the compression. The positive shift of G peak is related to the increase in sp3 bonds in sp2-dominant amorphous carbon37. The increase in D peak intensity occurs when the crystal symmetry of graphite or graphene is disrupted by local disorder, resulting from the localized formation of defects or sp3 bonds38,39,40. In addition, recent experimental studies on carbon nanotubes showed that the lateral compression of carbon nanotube could increase the D peak41. We expect that uniaxial compression could induce a similar topological change locally. If a slightly curved hexagonal planar structure is present in a nanopillar, uniaxial compression could fold such structure and increase the local curvature, enhancing the D peak intensity. Although it is difficult to experimentally confirm the local curvature change, our molecular dynamic (MD) simulation captured a permanent folding of hexagonal planar structure after uniaxial compression (The detailed discussion is also available in Supplementary Discussion 1; see also Supplementary Movie 2). Thus, the creation of sp3 bonds and the local topological change in internal structures could be the reasons for the increase in D peak intensity in our Raman spectra data.

The combination of EELS and Raman data suggests strongly that a local sp2-to-sp3 transition occurs during compression. In fact, the sp2-to-sp3 transition has been widely observed in amorphous carbon under hydrostatic42,43, biaxial44, and uniaxial compression45. Hydrostatic compression tests often apply extremely high pressure (10–40 GPa) to induce the sp2-to-sp3 transition. This raises a question of if the uniaxial fracture strength of our fully dense nanopillars, ~4 GPa, may be too low for such transition. However, it is important to consider that the strain is the more critical factor than the stress (or pressure) because the strain is directly related to the atomic displacement, which influences the sp2-to-sp3 transition. Note that hydrostatic pressure of 20–40 GPa changes the linear dimension of amorphous carbon by less than 10%. But in our case, the fracture strain is around 35%, which is 3 times larger than the hydrostatic pressure case. Therefore, it is feasible to induce a significant atomic displacement capable of triggering the sp2-to-sp3 transition within our nanopillar. Also, the stress required for the sp2-to-sp3 transition is strongly dependent on the initial carbon arrangement. The recent density functional theory calculation claimed that over 10% increase in sp3 content is possible through the sp2-to-sp3 transition in amorphous carbon with 1.8 g cm−3 in density (similar to our 1.6 g cm−3) only under around 5 GPa of hydrostatic pressure42. Based on all these results, our amorphous carbon could have an initial carbon arrangement that can be adjusted easily even at relatively low stress level.

One typical feature of the sp2-to-sp3 transition is the mechanical hysteresis46. This hysteresis is related to the different energy barriers between the forward (sp2 → sp3) and the backward (sp3 → sp2) transition (Fig. 3c). Due to the different energy barrier, the phase transformation during loading (sp2 → sp3) and unloading (sp3 → sp2) produces different critical stresses for transition under the load-controlled condition, which is our case. As a result, the stress-strain path is different between loading and unloading, i.e., mechanical hysteresis47.

To confirm that the closed hysteresis loops indeed exist in stress-strain data, a cyclic loading test was conducted on the fully dense carbon pillar. The loss factor (\({{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}\)) can be calculated with \({{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}=\frac{{{\boldsymbol{\Delta }}}{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{\pi }}}{{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}_{{{\mathbf{max }}}}}\) for the micropillar compression cyclic test48, where \({{\boldsymbol{\Delta }}}{{\boldsymbol{W}}}\) is the dissipated energy per stress-release cycle, and \({{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}_{{{\mathbf{max }}}}\) is the maximum stored energy per unit volume over the cycle. Our fully dense pillar showed the mechanical hysteresis loop (the magenta colored area in Fig. 3d) with \({{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}={{\mathbf{0}}}{{\mathbf{.}}}{{\mathbf{033}}}\), which corresponds to the high damping materials (\({{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}\, > \, {{\mathbf{0}}}{{\mathbf{.}}}{{\mathbf{015}}}\))49 and is close to the loss factor of commercial Nitinol (Ni-Ti) shape memory alloys (\({{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}={{\mathbf{0}}}{{\mathbf{.}}}{{\mathbf{028}}} \sim {{\mathbf{0}}}{{\mathbf{.}}}{{\mathbf{041}}}\)) (Cyclic stress-strain curves and loss factor data of all nanoporous nanopillars are available in Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table 6). Based on EELS, Raman spectra, and cyclic loading test, a local sp2-to-sp3 transition is likely to be the main mechanism of both elastic and plastic deformation. A reversible part of the sp2-to-sp3 transition produces large elastic strain and a high loss factor. The irreversible part of the sp2-to-sp3 transition produces plastic deformation, leading to a large fracture strain of up to 35%.

Atomistic simulations were used to probe how atomic arrangement is changed under uniaxial loading and unloading. The amorphous carbon structure with the similar mass density (1.6 g cm−3) with the high fraction of sp2 bonds (~90%) was constructed, and the fractions of sp2 and sp3 bonds were monitored during uniaxial compression up to 40% strain, which is similar to the experimental fracture strain (~35%), and during unloading. The simulation results show that the fraction of sp3 increases by ~13% at 40% strain, but a considerable amount of newly formed sp3 bonds is transformed back to sp2 bonds during unloading (Fig. 3e). This result is similar to the hydrostatic pressure studies showing that most newly formed sp3 bonds are transformed back to sp2 bonds during unloading46. When unloading is completed, only 3.7% of sp2 bonds were permanently reduced by forming the similar amount of sp3 bonds. This simulation result is similar to our EELS data that showed about 4% reduction of the sp2 bonds after unloading. Thus, our simulation data agrees well with our experimental findings and confirms the plastic strain resulted from the irreversible part of the sp2-to-sp3 transition. This atomic scale transformation also explains why the signature of plasticity could not be observed from the high-resolution SEM images even after the large amount of deformation (Fig. 2b). We also found that the slope of the simulated unloading curve changes nonlinearly when the new sp3 bonds are transformed back to the sp2 bonds (two broken red lines in Fig. 3f). This non-linear change resembles the shape of the experimental unloading curve (two broken red lines in Fig. 3d), which could be the main reason for mechanical hysteresis. Note that the high stress level of atomistic simulations is typical and unavoidable due to the extremely high strain rate50,51. We also studied the strain rate effect (see also Supplementary Discussion 2) and confirmed that the high stress level in our simulation data is directly associated with the strain rate. As discussed before, the strain is the primary factor to control the atomic displacement, which is directly related to the sp2-to-sp3 transition. Thus, our simulation results should be considered valid for studying the fundamental mechanisms of elastic and plastic deformation reasonably in terms of large strain (40%) similar to experimental value (35%).

Interestingly, plastic strain (Fig. 2g) and loss factor (see also Supplementary Table 6) of nanoporous nanopillars are generally lower than those of fully dense ones. These results can also be understood in terms of the sp2-to-sp3 transition. The sp2-to-sp3 transition is driven by compressive stress because the sp3 bond is more energetically preferred under compression. Thus, both plastic strain and loss factor must be affected by the distribution and magnitude of compressive stress. Because of complex nanoporous structures, ligaments in nanoporous nanopillars should undergo bending stress, which includes both compressive and tensile stresses. The local regions under tensile stress do not undergo the sp2-to-sp3 transition, leading to the lower plastic strain and loss factor of nanoporous nanopillars. However, the plastic strain and loss factor could be enhanced if the size of ligaments become extremely thin. As discussed in the previous section, the flaw tolerance effect at the nanoscale could suppress the fracture of ligaments in regions under tension and enable further deformation. This could be the reason for nanopillar with the highest porosity (59%) to exhibit higher fracture strain and higher loss factor than the nanopillar with the porosity of 51%.

Discussion

Mechanical characterizations revealed that all nanopillars in this study exhibit remarkably high yield and fracture strengths, which are 50–75% of the Suquet upper bound (Fig. 2f). In addition, our fully dense specimen has a low mass density (1.6 g cm−3), and the introduction of nanoscale pores reduces the mass density even further (0.66–0.82 g cm−3). As a result, the plot of the fracture strength versus mass density shows that our nanopillars are among the strongest materials for their mass density (Fig. 4a). These superior mechanical properties could result primarily from the ligament size effects and the sample size effects. The nanoscale thickness of ligaments is too small to contain any significant flaws that would detrimentally affect the strength, and the overall volume of nanopillars may not be large enough to contain flaws. As shown by the FIB-milled micropillar compression tests, the sample size effect seems to be relatively weak because the self-assembly of BBCPs produces uniform and ordered nanoporous structures, which preserves the consistent mechanical properties up to the micrometer scale. The sample size effect would be more observable if the sample dimension goes beyond millimeters and centimeters because the weaker spots will be statistically probable to be present in such large volume. It would be important to study the sample size effect in a larger length scale as a future work.

a Compressive strength vs. density. This plot includes all published data of nanoporous materials and nanolattices. Their citation is available in Supplementary Fig. 13; b Specific yield strength vs. fracture strain; c Specific Young’s modulus vs. specific yield strength. The broken line contour shows the magnitude of specific modulus of resilience.

In addition, our nanopillars exhibit large fracture strain (Fig. 2g) and high damping capability (Fig. 3d). Recent study on the state-of-the-art amorphous carbon nanolattices, which could be considered as a highly ordered porous structure, showed the ultrahigh breaking strength9, but they exhibited extreme brittleness with no measurable plastic strain and no damping capability. In contrast, our nanoporous amorphous carbon nanopillars are much more deformable than that of the 3D architected amorphous carbon nanolattice structures with the fracture strain of ~10% only. The latter requires a more time-consuming and costly fabrication process, not to mention the huge volume shrinkage during pyrolysis process which hampers precise control over the final feature dimensions. Also, for a given fracture strain, our materials possess the high specific strength, implying that they are highly deformable even with ultrahigh strength (Fig. 4b). Some high strength composites show relatively similar specific fracture strength, but their ductility is less than 1%, which is more than a magnitude smaller than that of our nanopillars (17–35%).

Due to the ultrahigh strength and low mass density, our materials exhibit the extraordinary combination of specific yield strength and specific Young’s modulus. They occupy the blank space in the plot of specific yield strength vs. specific Young’s modulus (Fig. 4c). This indicates that our materials exhibit the unprecedentedly high specific modulus of resilience (~50,000 J kg−1), which corresponds to the maximum possible elastic energy absorption and release per unit volume and per unit density. The straight contour lines show the magnitude of specific modulus of resilience. The specific modulus of resilience of our materials is certainly the highest within their range of specific yield strength and is comparable with that of elastomers, which show the highest modulus of resilience due to their extremely large elastic deformability.

As mentioned in the previous section, due to the reversible sp2-to-sp3 transition, our materials can also be classified as highly damping capable materials, which have the loss factor of 0.015–0.033. Thus, our amorphous carbon nanopillar and its nanoporous structures provide unusual combinations of lightweight, high strength, large fracture strain, and high damping capability. Although there have been similar studies on micromechanical testing of fully dense amorphous carbon17,52,53, these systems used different initial conditions with either the crumbled graphite networks or the higher density of sp3 bonds, and their mass density was not measured experimentally. More importantly, our work is unique in aspect that the mass density is tunable by introducing nanoporous structure with ultrahigh strength, a result that no other approach has achieved. Moreover, note that the Suquet upper bound is higher than the current yield strength (Figs. 2f and 4a). This implies that even though our produced nanoporous carbon nanopillars exhibit superior strength, it will be interesting to investigate the different pore structures to further improve the yield strength in the future work.

It is also noteworthy to emphasize that our synthesis method is both rapid and scalable. It is possible to create both fully dense and nanoporous structures with even centimeter-scale dimensions in width and hundreds of micrometers in thickness (see also Supplementary Method 3). This efficient and scalable fabrication method makes our materials more suitable for potential engineering applications, compared to nanolattices that have limited scalability beyond 200 μm in dimension. Moreover, there is a large degree of freedom in materials design. The pore distribution can be varied by adding both linear block copolymer (LBCP) and BBCP or by varying the molecular weight of BBCP, so the non-uniform pore distribution, for instance, bimodal distribution, can be easily created54,55. Metallic or ceramic nanoparticles with the diameter less than 5 nm can be embedded into ligaments of nanoporous structures56. A nanoscale ceramic layer can be coated on the pore surfaces using the atomic layer deposition18. All these nanoporous carbon and their composite materials will provide a wide range of structure-property-processing controllability. In summary, lightweight, superior mechanical properties, scalable fabrication method, and tunable microstructures of nanoporous amorphous carbon promote the fabrication of not only advanced structural materials for military and aerospace applications but also mechanically robust nanoporous structures for energy, biomedical, filtration, and catalyst applications.

Methods

Materials and reagents

Poly(ethylene glycol) monomethyl ether (Mw—4.0 kg mol−1) was obtained from TCI (Portland, USA) and monocarbinol-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Mw—4.8 kg mol−1) was purchased from Gelest (Morrisville, PA, USA). Grubbs third-generation catalyst, exo-5-norbornene carboxylic acid, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC, >99.0%), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, >99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and were used without further purification. Anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) and anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF, 99.9%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Silicon wafers were purchased from University Wafer, Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). Phenol (>99%) and formaldehyde solution (~36% in H2O) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 7–8 % vinyl methylsiloxane-dimethylsiloxane, 25–30% methylhydrosiloxane-dimethylsiloxane were obtained from Gelest (Morrisville, PA, USA). Platinum-divinyltetramethyldisiloxane and 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl-2,4,6,8-tetravinylcyclotetrasiloxane were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Synthesis of BBCP and PF resin

Polydimethylsiloxane-b-poly(ethylene oxide) (PDMS-b-PEO) BBCP was synthesized following ring opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) using Grubbs generation III catalyst following our previous report (also described in Supplementary Method 4)19,54,55. The molecular weight of BBCP was varied by changing the overall degree of polymerization (DP) which in turn was controlled by changing the feed ratio of monomer and catalyst54. The obtained molecular weight at different DP was calculated to be 250 KDa mol−1, 500 KDa mol−1, and 800 KDa mol−1.

PF resin was synthesized in basic polymerization medium54. Phenol was melted at 42 °C and 20 wt.% of NaOH (sodium hydroxide) was added dropwise to it. Formaldehyde was added in the molar ratio of 2 as compared to that of phenol and the entire mixture solution was stirred at 70 °C for 1 h. After cooling down the mixture, the solution pH was neutralized using 0.5 M HCl solution. Water was removed in presence of nitrogen flow overnight, following that ethanol was added to the solution to remove the formed sodium chloride (NaCl). Finally, ethanol was removed by nitrogen and redissolved in the THF to get the desired concentration.

Fabrication of nanoimprinted nanopillars

The carbon precursor film is comprised of PDMS-b-PEO BBCP (M.W. 500 KDa mol−1) as the soft sacrificial template (porogen) and PF resin as the carbon source. The BBCP and PF resin were dissolved in THF separately to achieve a concentration of 40 and 50 mg mL−1, respectively. The BBCP and PF resin were added in the different weight ratio namely 1:1.5, 1:2, 1:3 and 1:4 and the solvent was evaporated with a nitrogen flow to increase the concentration to about 300 mg mL−1. Note that the weight ratio of 1:1 or lower could not be used because the fabrication of carbon precursor nanopillars using NIL is challenging due to relatively small amount of crosslinking segment (that is PF resin), which results in the fragile imprinted structure. The prepared solution was spin-coated at 1000 rpm for 30 s on Si wafer substrate. The substrate was ultrasonically cleaned with isopropanol and deionized water for 10 min each, followed by UV–ozone treatment for 15 min prior to coating. Carbon precursor film was patterned via NIL using h-pdms stamp. H-pdms stamp was placed on spin-coated carbon precursor film followed by heating it at 170 °C for 10 min under constant pressure of 180 psi. Applied pressure and temperature ensured pattern transfer from the h-pdms stamp to the carbon precursor film with simultaneous crosslinking of the PF resin. Preparation of h-pdms stamp from the Si imprint master was carried out as reported previously (also described briefly in Supplementary Method 5)57. Stamp was removed from the carbon precursor film after cooling down the system to the room temperature. Finally, imprinted carbon precursor film was carbonized in tube furnace at 750 °C in nitrogen atmosphere for 1 h. with the heating rate of 10 °C min−1. This resulted in the formation of nanostructured mesoporous carbon with film thickness of ~5 μm. During the carbonization process BBCP degraded completely and PF resin got converted into carbon resulting in the formation of porous carbon with the nanostructure transferred using NIL. Different weight ratios between BBCP and PF resin were chosen to vary porosities in the obtained mesoporous carbon. Moreover, pore size was varied by utilizing the BBCP of different molecular weight (250 KDa mol−1, 500 KDa mol−1, and 750 KDa mol−1) with the constant weight ratio of 1:2 between BBCP and PF resin. The residual carbon film from the surface of nanostructured porous carbon was removed using reactive ion etching in O2 plasma (HF power—10 W, pressure—12 mtorr, O2—40 sccm) for 90 s. Fully dense patterned carbon film was fabricated using the same procedure but without any BBCP in it. We also prepared nanoporous carbon thin film following the procedure described above for porosity and density measurement without performing NIL (shown in Supplementary Method 1). Moreover, to demonstrate the versatility of this approach we produced nanoporous carbon with different architecture specially motheye, pyramid and pillar by using their respective desired h-pdms stamp keeping other processes same (shown in Supplementary Fig. 2).

Nanomechanical experiments

Nanoindentation was performed on the thin film region of the carbon sample at room temperature by using an iNanoTM system (Nanomechanics, TN, USA). The indentation was performed utilizing the standard Berkovich tip nanoindentation technique, with an indentation strain rate of 0.2 s−1. The indentation depths were set as 1/10 of the thickness of the carbon samples to make sure that the indentation data are not affected by the silicon substrate.

In situ uniaxial compression tests were performed by the nanoindenter (NanoflipTM, Nanomechanics Inc., TN, USA) with a flat diamond tip, which was installed in a field-emission gun scanning electron microscope (JSM-6335F, JEOL, Japan). The nanopillars were compressed under a constant displacement rate of 10 nm s−1. The stress-strain curves were obtained through the corresponding load-displacement data and were corrected by the Sneddon punch method58. The yield strength was obtained by measuring a flow strength at 1% plastic strain, which is determined at the intersecting point of stress-strain curve and a straight line that has the slope of Young’s modulus and pass 0.01 of strain at the strain axis. The entire deformation process was also recorded to avoid strain measurement errors.

The cyclic compression tests were also performed under the same condition of maximum and minimum stresses. The maximum stress of cyclic tests was set as ~95% of the average fracture stress for each porosity carbon pillars, and the minimum stress was set as 12% of the maximum stress. This wide stress range enabled us to obtain a sufficient size of hysteresis loop for the precise measurement of the loss factor. Each cyclic test consisted of six loading and unloading cycles, employing a constant displacement rate of 25 nm s−1 (2.5 times that of the uniaxial compression test) to reduce the overall experimental time. The initial loading curve of the cyclic test closely matched that of the uniaxial compression test, confirming that the chosen displacement rate does not affect the mechanical behavior, compared to uniaxial compression test. The electron beam was kept on during all mechanical testing, but we confirmed that the electron beam condition in our study does not affect the mechanical data (see Supplementary Discussion 3).

Microstructure characterization

The microstructure of porous and fully dense carbon pillars was characterized by Titan Themis AC-STEM (Thermo Fisher) at the accelerating voltage of 300 kV. The cross-sectional TEM samples were prepared using the lift-out technique with an FIB instrument (FEI Helios, Therma Fisher). A protective carbon layer was first deposited on the carbon thin film and the micropillar. Milled graduated trenches were introduced into the bottom Si substrate utilizing Ga+ ion beams. With the samples mounted on the micromanipulator, careful cutting was carried out on the side and bottom sections. Subsequently, the samples were lifted out and positioned onto a copper grid. Finally, a thorough cleaning and thinning process was performed until achieving the desired final thin TEM sample. EELS analysis was also performed in Titan Themis AC-STEM with the accelerating voltage of 250 kV and the EELS curves were analyzed by Two-window method36 to calculate the relative fractions of sp2 and sp3 phases.

The phase transformation upon compression was characterized using Raman spectroscopy with a 633 nm laser (Renishaw Ramascope 2000). The Raman spectra were fitted with Gaussian peaks to quantitatively evaluate the D and G band changes.

Molecular dynamics simulations

The amorphous carbon structures were generated employing two key methods: the liquid-quench method59,60. The overall process of generating the model carbon structures, based on an experimental density of 1.6 g cm−3, involves seven steps (more details are described in Supplementary Method 2). Based on the generated amorphous configuration, the uniaxial mechanical test was conducted using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) package (version: lammps-20210929.tar.gz, released on 09/29/2021)61. Interaction potentials involving carbon particles are characterized by Adaptive Intermolecular Reactive Empirical Bond Order (AIREBO) Potential62.

During the loading process, a relaxation time of 500 ps was first performed under the NPT ensemble at a constant temperature of 300 K and pressure of 0.0 MPa. Following the relaxation period, non-equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (NEMD) simulations were conducted to explore the system’s response to loading-unloading with the strain rate, 109 s−1, at 300 K and a timestep of 0.2 fs under the \({{\boldsymbol{N}}}{{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{ij}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{ij}}}}{{\boldsymbol{T}}}\) ensemble. During the loading and unloading processes, carbon hybridization (sp, sp2 and sp3) was also computed based on the number of nearest neighbor carbon atoms within a cutoff radius of 2.0 Å. We defined the bond type of a carbon atom based on a coordination criterion as follows: a carbon atom is labeled as sp if it is bonded to 2 other carbon atoms, sp2 if it forms bonds with 3 other carbon atoms, and sp3 if it is bonded to 4 other carbon atoms, all within a 2.0 Å cutoff radius.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of the study are included in the main text and Supplementary Information files. Raw data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Lu, G. Q. M. & Zhao, X. S. Nanoporous Materials: Science and Engineering, Vol. 4 (World Scientific, 2004).

Hadden, M., Martinez-Martin, D., Yong, K.-T., Ramaswamy, Y. & Singh, G. Recent advancements in the fabrication of functional nanoporous materials and their biomedical applications. Materials 15, 2111 (2022).

Gibson, L. J. & Ashby, M. F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties. Cambridge Solid State Science Series (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Ashby, M. F. & Cebon, D. Materials selection in mechanical design. J. Phys. IV France 3, C7-1 (1993).

Zhang, H. et al. Approaching the ideal elastic strain limit in silicon nanowires. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501382 (2023).

Greer, J. R., De Hosson, J. & Th, M. Plasticity in small-sized metallic systems: intrinsic versus extrinsic size effect. Prog. Mater. Sci. 56, 654–724 (2011).

Zhu, T. & Li, J. Ultra-strength materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 55, 710–757 (2010).

Dang, C. et al. Achieving large uniform tensile elasticity in microfabricated diamond. Science 371, 76–78 (2021).

Biener, J. et al. Size effects on the mechanical behavior of nanoporous Au. Nano Lett. 6, 2379–2382 (2006).

Saito, Y. et al. Preparation of ordered nanoporous indium tin oxides with large crystallites and individual control over their thermal and electrical conductivities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 15373–15382 (2021).

Yang, W. et al. Light, strong, and stable nanoporous aluminum with native oxide shell. Sci. Adv. 7, eabb9471 (2023).

Jang, D. & Greer, J. R. Transition from a strong-yet-brittle to a stronger-and-ductile state by size reduction of metallic glasses. Nat. Mater. 9, 215–219 (2010).

Östlund, F. et al. Brittle-to-ductile transition in uniaxial compression of silicon pillars at room temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 2439–2444 (2009).

Zou, Y. et al. Superior room-temperature ductility of typically brittle quasicrystals at small sizes. Nat. Commun. 7, 12261 (2016).

Lee, S.-W., Jafary-Zadeh, M., Chen, D. Z., Zhang, Y.-W. & Greer, J. R. Size effect suppresses brittle failure in hollow Cu60Zr40 metallic glass nanolattices deformed at cryogenic temperatures. Nano Lett. 15, 5673–5681 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Theoretical strength and rubber-like behaviour in micro-sized pyrolytic carbon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 762–769 (2019).

Hu, M. et al. Compressed glassy carbon: an ultrastrong and elastic interpenetrating graphene network. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603213 (2017).

Bhardwaj, A. et al. Large-pore ordered mesoporous turbostratic carbon films prepared using rapid thermal annealing for high-performance micro-pseudocapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 61027–61038 (2021).

Yun, Y. S. & Jin, H.-J. Electrochemical performance of heteroatom-enriched amorphous carbon with hierarchical porous structure as anode for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 108, 311–315 (2013).

Jain, S., Sharma, A. & Basu, B. Vertical electric field stimulated neural cell functionality on porous amorphous carbon electrodes. Biomaterials 34, 9252–9263 (2013).

Bauer, J., Schroer, A., Schwaiger, R. & Kraft, O. Approaching theoretical strength in glassy carbon nanolattices. Nat. Mater. 15, 438–443 (2016).

Li, Q. et al. Mechanical nanolattices printed using nanocluster-based photoresists. Science 378, 768–773 (2022).

Neidhardt, J., Hultman, L. & Czigány, Z. Correlated high resolution transmission electron microscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies of structured CNx (0<x<0.25) thin solid films. Carbon 42, 2729–2734 (2004).

Shiell, T. B. et al. Graphitization of glassy carbon after compression at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 215701 (2018).

Shiell, T. B. et al. Nanocrystalline hexagonal diamond formed from glassy carbon. Sci. Rep. 6, 37232 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Strong amorphous carbon prepared by spark-plasma sintering C60. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 104, 1655–1660 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. Integration of nanoimprint lithography with block copolymer directed self-assembly for fabrication of a sub-20 nm template for bit-patterned media. Nanotechnology 25, 395301 (2014).

Lee, S. et al. FIB-induced dislocations in Al submicron pillars: annihilation by thermal annealing and effects on deformation behavior. Acta Mater. 110, 283–294 (2016).

Bauer, J. et al. Nanolattices: an emerging class of mechanical metamaterials. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701850 (2017).

Suquet, P. M. Overall potentials and extremal surfaces of power law or ideally plastic composites. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 41, 981–1002 (1993).

Dong, L., Deshpande, V. & Wadley, H. Mechanical response of Ti–6Al–4V octet-truss lattice structures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 60–61, 107–124 (2015).

Crook, C. et al. Plate-nanolattices at the theoretical limit of stiffness and strength. Nat. Commun. 11, 1579 (2020).

Banerjee, A. et al. Ultralarge elastic deformation of nanoscale diamond. Science 360, 300–302 (2018).

Meza, L. R., Das, S. & Greer, J. R. Strong, lightweight, and recoverable three-dimensional ceramic nanolattices. Science 345, 1322–1326 (2014).

Michelson, A., Flanagan, T. J., Lee, S.-W. & Gang, O. High-strength, lightweight nano-architected silica. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 4, 101475 (2023).

Bruley, J., Williams, D. B., Cuomo, J. J. & Pappas, D. P. Quantitative near‐edge structure analysis of diamond‐like carbon in the electron microscope using a two‐window method. J. Microsc. 180, 22–32 (1995).

Ferrari, A. C. & Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 61, 14095 (2000).

Lucchese, M. M. et al. Quantifying ion-induced defects and Raman relaxation length in graphene. Carbon 48, 1592–1597 (2010).

Eckmann, A. et al. Probing the nature of defects in graphene by Raman spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 12, 3925–3930 (2012).

Cançado, L. G. et al. Disentangling contributions of point and line defects in the Raman spectra of graphene-related materials. 2d Mater. 4, 025039 (2017).

Picheau, E. et al. Intense Raman D band without disorder in flattened carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano 15, 596–603 (2021).

Jiang, X., Århammar, C., Liu, P., Zhao, J. & Ahuja, R. The R3-carbon allotrope: a pathway towards glassy carbon under high pressure. Sci. Rep. 3, 1877 (2013).

Shiell, T. B. et al. In situ analysis of the structural transformation of glassy carbon under compression at room temperature. Phys. Rev. B 99, 24114 (2019).

McCulloch, D. G., McKenzie, D. R. & Goringe, C. M. Ab initio simulations of the structure of amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 61, 2349 (2000).

Zhao, Y., Qian, C., Gladkikh, V. & Ding, F. Simulated pressure-temperature carbon structure map obtained through uniaxial compression of Bulk C60. Carbon 202, 554–560 (2023).

Zeng, Z. et al. Structural transition in cold-compressed glassy carbon. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 033608 (2019).

Sypek, J. T. et al. Superelasticity and cryogenic linear shape memory effects of CaFe2As2. Nat. Commun. 8, 1083 (2017).

Juan, J. S., Nó, M. L. & Schuh, C. A. Nanoscale shape-memory alloys for ultrahigh mechanical damping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 415–419 (2009).

Zhang, J., Perez, R. J. & Lavernia, E. J. Documentation of damping capacity of metallic, ceramic and metal-matrix composite materials. J. Mater. Sci. 28, 2395–2404 (1993).

Park, H. et al. Toward the constitutive modeling of epoxy matrix: temperature-accelerated quasi-static molecular simulations consistent with the experimental test. Compos. B Eng. 142, 131–141 (2018).

Fan, J., Anastassiou, A., Macosko, C. W. & Tadmor, E. B. Molecular dynamics predictions of thermomechanical properties of an epoxy thermosetting polymer. Polymer 196, 122477 (2020).

Yoon, J. et al. In situ tensile and fracture behavior of monolithic ultra-thin amorphous carbon in TEM. Carbon 196, 236–242 (2022).

Liu, C., Lin, Y., Zhou, Z. & Li, K.-Y. Dual phase amorphous carbon ceramic achieves theoretical strength limit and large plasticity. Carbon 122, 276–280 (2017).

Fei, H.-F. et al. Ordered nanoporous carbons with broadly tunable pore size using bottlebrush block copolymer templates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 17006–17014 (2019).

Fei, H.-F. et al. One-step synthesis of hierarchical, bimodal nanoporous carbons via co-templating with bottlebrush and linear block copolymers. Chem. Mater. 32, 6055–6061 (2020).

Song, D.-P. et al. Millisecond photothermal carbonization for in-situ fabrication of mesoporous graphitic carbon nanocomposite electrode films. Carbon 174, 439–444 (2021).

Einck, V. J. et al. Scalable nanoimprint lithography process for manufacturing visible metasurfaces composed of high aspect ratio TiO2 meta-atoms. ACS Photonics 8, 2400–2409 (2021).

Lee, S.-W., Han, S. M. & Nix, W. D. Uniaxial compression of fcc Au nanopillars on an MgO substrate: the effects of prestraining and annealing. Acta Mater. 57, 4404–4415 (2009).

Galli, G., Martin, R. M., Car, R. & Parrinello, M. Structural and electronic properties of amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 555 (1989).

Rosen, J., Warschkow, O., McKenzie, D. R. & Bilek, M. M. M. Amorphous and crystalline phases in thermal quench simulations of alumina. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 204709 (2007).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Stuart, S. J., Tutein, A. B. & Harrison, J. A. A reactive potential for hydrocarbons with intermolecular interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 112, 6472–6486 (2000).

Acknowledgements

A.B., S.N., and J.J.W. acknowledge support from the Office of Naval Research (N00014-23-9-0008) through the American Lightweight Materials Manufacturing Innovation Institute. Z.L. and S.-W.L. acknowledge support from the UConn/Thermo Fischer Scientific Center for Advanced Microscopy and Materials Analysis (CAMMA) for the FIB milling, TEM, and EELS experiment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., A.B., J.J.W. and S.-W.L. conceived and designed the experiments and analysis. Nanomechanical testing, TEM, EELS, and Raman Spectroscopy experiments were carried out and analyzed by Z.L. and S.-W.L. Synthesis of BBCP and PF, self-assembly, and NIL experiments were carried out and analyzed by A.B. and J.J.W. W.Z. and T.T.T. helped Z.L. to obtain the in situ deformation video. Molecular dynamic simulations were carried out by and analyzed by J.H. and Y.L. A.M. and S.N. conducted the porosity measurement. Z.L., A.B., J.J.W. and S.-W.L. wrote the paper together. J.J.W. and S.-W.L. supervised and provided support through the paper. All authors have commented and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Bhardwaj, A., He, J. et al. Nanoporous amorphous carbon nanopillars with lightweight, ultrahigh strength, large fracture strain, and high damping capability. Nat Commun 15, 8151 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52359-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52359-6

This article is cited by

-

Functional nano-architected mechanical metamaterials and devices

npj Metamaterials (2026)

-

Graphene–amorphous carbon with interwoven networks for enhanced strength

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Mechanically resilient 3D lattices with soft–hard bicontinuous nanostructures via phase-separated interpenetrating composites

Scientific Reports (2025)