Abstract

Understanding the causes of the ~90 ppmv atmospheric CO2 swings between glacial and interglacial climates is an important open challenge in paleoclimate research. Although the regularity of the glacial-interglacial cycles hints at a single driving mechanism, Earth System models require many independent physical and biological processes to explain the full observed CO2 signal. Here we show that biologically sequestered carbon in the ocean can explain an atmospheric CO2 change of 75 ± 40 ppmv, based on a mass balance calculation using published carbon isotopic measurements. An analysis of the carbon isotopic signatures of different water masses indicates similar regenerated carbon inventories at the Last Glacial Maximum and during the Holocene, requiring that the change in carbon storage was dominated by disequilibrium. We attribute the inferred change in carbon disequilibrium to expansion of sea-ice or change in the overturning circulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Measurements of atmospheric CO2 trapped in ancient ice show that its concentration increased from roughly 190 ppmv at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM; from 23,000 until 19,000 years before present) to ~280 ppmv during the pre-industrial Holocene1. Over the past 40 years, explanations for this deglacial CO2 increase have relied primarily on numerical modeling studies. Early box models2,3,4 suggested that rather modest changes in Southern Ocean nutrient utilization or air-sea gas exchange could account for the full 90 ppmv glacial-interglacial CO2 change. However, studies with more comprehensive Earth System models found much weaker impacts of Southern Ocean processes on atmospheric CO25,6. The discrepancies have been attributed to the crude representation of the ocean circulation7 and air-sea equilibration8 in box models. The long-standing consensus is that while changes in Southern Ocean processes played an important role, several other concurrent physical, chemical and biological mechanisms are needed to explain the total ocean carbon uptake during glacial climates9,10,11,12,13. Furthermore, these mechanisms must be imposed externally one by one: models that allow CO2 to evolve freely, without incorporating additional glacial mechanisms, often predict elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations at the LGM14. The requirement of many independent separate mechanisms is difficult to reconcile with the evidence that the magnitude of the glacial-interglacial CO2 swings has been remarkably constant over the last few glacial cycles, appearing to demand that all the driving mechanisms be tightly coupled. Modeling the coupling between the various biogeochemical and physical mechanisms affecting the carbon cycle is challenging for the modern ocean and even more so for the poorly constrained LGM paleo-environment. As an alternative approach, we query the carbon isotopic record to identify what mechanisms controlled the glacial-interglacial CO2 swings.

On the timescales at which Quaternary deglaciations occur (~5000 years), two main carbon reservoirs have a significant exchange with the atmosphere: organic carbon stored on land, and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) stored in the ocean. Proxies and vegetation models both suggest that carbon in terrestrial biomass increased during the deglaciation15,16,17, making the land a sink that would have resulted in a ~20 ppmv atmospheric CO2 decrease18. The available evidence thus points toward the ocean as the source of the deglacial increase in atmospheric CO2.

Carbon storage in the ocean is primarily set by its solubility in water as determined by temperature, salinity and total alkalinity (a measure of acid buffering capacity). The solubility of CO2 in water decreases as the temperature and salinity rise. On one hand, the ~3 °C increase in average ocean temperature from the LGM to the Holocene would have resulted a ~30 ppmv atmospheric CO2 increase19. On the other hand, the decrease in ocean salinity associated with the melting of most Northern Hemisphere ice sheets would have decreased atmospheric CO2 by ~6 ppmv20. Thus, accounting for the relatively well constrained changes in terrestrial biomass, ocean temperature, and salinity leaves essentially the entire ~90 ppmv of the atmospheric CO2 rise unexplained. Here, we investigate the hypothesis that marine productivity played a key role in the LGM-to-Holocene CO2 change.

Marine photosynthesizers grow by taking up DIC and nutrients in the euphotic layer of the ocean. When they die, part of their biomass sinks into deeper waters where it is consumed by organisms such as bacteria. Eventually, the organic carbon is remineralised into DIC through respiration at different trophic levels. As a result of this biological carbon pump, the DIC concentration is higher in the deep ocean than at the surface21. In upwelling regions such as the Southern Ocean, carbon-rich deep waters come in contact with the atmosphere. This leads to outgassing from the ocean to the atmosphere, since these waters are oversaturated in carbon. In the present climate the oversaturation is not completely erased, because the equilibration process takes ~1 year, which is of the same order as the surface residence time of the water in the Southern Ocean. As a result, a significant fraction of upwelled carbon of biological origin is resubducted into the ocean interior, before it has fully equilibrated with the atmosphere22. This disequilibrium DIC increases the amount of carbon stored in the ocean, in addition to carbon storage due to sinking of organic matter11,13,23. Disequilibrium DIC can also have a physical origin as is the case in the North Atlantic. Here the cooling of Northward-flowing surface water results in a negative disequilibrium, i.e., the DIC of the surface waters is lower than the saturated value. This has been termed the physical disequilibrium DIC as opposed to the biological disequilibrium DIC12 that we will be focusing on.

Using proxy reconstructions of carbonate ion concentrations at the LGM, Goodwin & Lauderdale24 estimated a 55 ± 15 ppmv storage of carbon in the ocean at the LGM, but they could not distinguish between the relative contributions of soluble, respired, or disequilibrium DIC. Recently, using deep-ocean oxygen concentration reconstructions at the LGM25,26, Vollmer et al.27 inferred that a more efficient LGM biological pump accounted for a 64 ± 28 ppmv atmospheric CO2 drawdown before carbonate compensation, i.e., the stabilization of CO2 levels through the dissolution of calcium carbonate in the ocean. However, any estimate of carbon storage based on oxygen is complicated by CO2’s much longer air-sea equilibration time (~1 year) compared to oxygen (~1 month). To assess the potential bias in this estimate of biologically sequestered carbon in the ocean, we perform a similar calculation using stable carbon isotopic ratios (δ13C) instead of oxygen proxies. We focus on the vertical δ13C gradient in the ocean, which provides another measure of sequestered carbon28,29,30,31. Since δ13C has a much longer equilibration timescale (~10 years) than CO232,33, we expect the bias in this estimate to be in the opposite direction compared to the oxygen-based estimate in27. Thus, our analysis provides an independent constraint on how much of the atmospheric CO2 change can be attributed to a change in biologically sequestered carbon in the ocean.

Many physical, chemical, and biological processes involve isotopic fractionation, which means that they select for one isotope of an element over a different isotope of that same element. Therefore, isotopic ratios can serve as proxies for the underlying processes. Here we focus on carbon, which exists in two stable isotopic forms: 12C (light carbon) and 13C (heavy carbon). The isotopic composition of carbon in the atmosphere and ocean is typically quantified in terms of the ratio of the heavy to light stable isotopes, \(R=\frac{\scriptstyle{{13}\atop}{{\rm{C}}}}{\scriptstyle {{12}\atop}{{\rm{C}}}}\). Since R is very small (≃0.011) and we care about deviations from its standard value (Rs), it is common practice to use the quantity \({\delta }^{13}{{\rm{C}}}=\frac{R-{R}_{s}}{{R}_{s}}\times\) 1000‰. The value of δ13C in past atmospheres is measured from gas bubbles trapped in ice cores. The ocean values are inferred from the isotopic composition of calcium carbonate shells of benthic foraminifera buried in sediments.

On average, δ13C is nearly 7‰ higher in the ocean than in the atmosphere. This overall fractionation is the result of two processes. First, isotopic fractionation associated with air-sea gas exchange leads to the δ13C of surface ocean DIC being ~8–10‰ higher than the atmosphere34. Second, the photosynthetic process has a preference for 12C over 13C. As a result, the δ13C of organic carbon is on average ~25‰ lower than surface ocean DIC30. Sinking and respiration of organic matter then adds some of this isotopically light carbon to the deep ocean, making the average δ13C of ocean DIC slightly lower than its surface value. Thus, biological activity decreases the difference in δ13C between the atmosphere and the ocean average.

In Fig. 1, we show the evolution of: (a) atmospheric pCO2 based on Antarctic ice cores35; and (b) δ13C over the last 20,000 years for the atmosphere, based on Antarctic ice cores36, as well as δ13C for the global ocean average, based on a compilation of 127 sediment cores from the different oceans (data details and core locations can be found in31). Atmospheric δ13C is a proxy for the distribution of carbon across different reservoirs, rather than the amount of carbon in the atmosphere37. As such, it behaved rather differently from atmospheric pCO2 across the deglaciation from the LGM into the Holocene. While atmospheric pCO2 increased almost monotonically from 18 to 11 kyr BP, atmospheric δ13C first decreased and then increased. The sharp drop between 17 and 16 kyr BP has been attributed to the outgassing of isotopically light carbon from the ocean36 and the release of terrestrial carbon38. From 12 kyr BP until 6 kyr BP, atmospheric δ13C increased at approximately the same rate as the average ocean δ13C. This has been interpreted as a result of the regrowth of boreal forests36. However, caution should be exercised when interpreting such transient deglacial δ13C changes in terms of mass fluxes. Deglaciations are, by definition, times of rapid climatic change and an unstable global carbon cycle. For example, the thawing permafrost and retreating ice sheets may have led to the oxidation of organic matter39 or even of exhumed petrogenic carbon40. Thus, isotopically light carbon from reservoirs other than the ocean would have been released to the atmosphere, temporarily increasing the ocean-atmosphere δ13C difference. Eventually, this temporary increase would have been erased by re-equilibration between the ocean and the atmosphere. In other words, the ocean-atmosphere δ13C difference provides a more unambiguous measure of biologically sequestered carbon in the ocean for times with a relatively stable climate, such as the LGM and Holocene, compared to periods of rapid change, such as the deglaciation. As the absolute changes in the size of other mobile carbon stores (such as terrestrial biomass) are small relative to the entire ocean-atmosphere carbon inventory, the effect of these reservoirs on the total CO2 change after equilibration must also be small. By focusing on changes in the overall difference between atmospheric and deep ocean δ13C during periods of slow change (the LGM and the Holocene), we link the vertical gradients in isotopic composition directly to changes in quasi-steady state carbon storage in the sea.

a Measured atmospheric pCO2 (in red, reproduced from ref. 35) from 20 to 6 kyr before present. b Measured atmospheric (red, left vertical axis, reproduced from ref. 36) and ocean-average (purple, right vertical axis, reproduced from ref. 31) δ13C from 20 to 6 kyr before present. The vertical arrows indicate the larger δ13C difference between the ocean (δo) and atmosphere (δa) during the Holocene than at the Last Glacial Maximum. A map with the locations of the 127 core sites used for the ocean-average δ13C was provided in ref. 31. In both panels, shaded areas indicate 2-σ uncertainty intervals of the measurements. Note that the vertical axes have different scales and that time runs forward to the right.

Based on the impact of temperature on physical fractionation alone, one would expect the difference between the δ13C of the ocean and the atmosphere to have decreased from the LGM to the Holocene. The opposite is observed: the difference in δ13C between the ocean average and the atmosphere increased from 6.4 ± 0.1‰ at the LGM to 6.7 ± 0.1‰ during the Holocene. This is consistent with a larger inventory of biologically sequestered carbon in the ocean at the LGM than during the Holocene, which we quantify in the next Section.

Results

This section sketches our budget calculations, with the details provided in the “Methods” section. We formulate a budget for δ13C that we convert into a carbon budget using the connections between isotopic fractionation and carbon cycle processes. More specifically, we use the known fractionation associated with air-sea equilibration to estimate its contribution to the overall observed LGM-Holocene δ13C changes. Then, by placing reasonable boundaries on the disequilibrium component of the fractionation, we calculate a residual change δ13C that we attribute to a deglacial decrease in the biologically sequestered carbon inventory.

Ocean carbon reservoirs

To understand the impacts of different processes, it is useful to divide the ocean carbon into saturated, disequilibrium, and regenerated components41,42. The saturated carbon is defined as the DIC concentration that a water mass would have under perfect air-sea equilibration just before it leaves the surface to sink into the ocean interior. After subduction, a water mass collects sinking organic material that is oxidized by deep-sea organisms such as bacteria. The regenerated carbon is defined as the amount of DIC added to a water mass through this process. The disequilibrium carbon is then the difference between the actual DIC concentration and the sum of the saturated and regenerated carbon. At the ocean surface, the disequilibrium carbon concentration is equal to the actual air-sea carbon disequilibrium (regenerated carbon is equal to zero at the surface by definition).

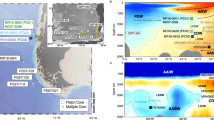

Figure 2 illustrates the role of the global ocean overturning circulation in the ocean-atmosphere partitioning of carbon, δ13C, and oxygen throughout the deep ocean. The overturning circulation consists of two main components: the surface circulation (upper ~1 km, not shown in the figure) and the deep circulation (below ~1 km depth). The deep circulation sketched in Fig. 2 consists of sinking water into the deep ocean through convection near Greenland and Antarctica, as well as through upwelling of deep water across various regions of the World Ocean. Deep water formed near Greenland flows southward and fills most of the deep Atlantic Ocean, as represented by the blue line in Fig. 2A. Deep water formed near Antarctica fills the deep Indian and Pacific Oceans, as represented by the black line in Fig. 2A. The two branches come to the surface in the Southern Ocean where they connect resulting in a figure-eight global overturning loop43. Due to the relatively long residence of surface water in the Atlantic, deep water forming near Greenland (vertical blue line) is approximately equilibrated with the atmosphere in terms of oxygen and carbon44. As this deep water flows southward in the ocean interior (lower horizontal blue line), it collects regenerated carbon when sinking organic particles are respired back to their inorganic constituents. In this process, oxygen is progressively depleted and the δ13C of the water mass decreases because of the particles’ low δ13C value (due to isotopic fractionation during photosynthesis). Water enriched in regenerated carbon continues South until it upwells in the Southern Ocean (slanted blue line), which gives rise to a large air-sea DIC disequilibrium equivalent to the actual air-sea pCO2 difference. As regenerated carbon is equal to zero at the surface by definition, regenerated carbon is converted into (relabeled as) disequilibrium carbon once the deep water reaches the surface. This disequilibrium is partly, but not entirely, eroded before the water subducts near Antarctica due to the relatively short 1-year residence time of surface water in the Southern Ocean22,44.

A The paths of the Northern (blue) and Southern (black) overturning cells for the modern ocean with the processes that move carbon and isotopes in the sea (air-sea gas exchange, biological export, and flow). B A zoom-in on the Southern portion of the Southern overturning cell shows how oxygen, carbon, and carbon isotopes interact with the atmosphere and sinking particles to generate disequilibrium.

We will be using msat, mreg, and mdis for the total oceanic inventories of saturated, regenerated, and disequilibrium carbon, respectively. The total carbon inventory, m, is thus the sum of these three components:

We define the sum of the regenerated and disequilibrium carbon as the (biologically) sequestered carbon mseq, similar to45:

We are using the term biologically sequestered carbon, because the disequilibrium carbon has a primarily biological origin. This does not imply that the sequestration is driven solely by biology, as sea ice and the ocean circulation play key roles in maintaining the carbon disequilibrium.

Bulk biologically sequestered carbon budget

Now we divide the ocean-average δ13C into contributions from saturated and sequestered carbon (\({\bar{\delta }}_{o,sat}\) and \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,seq}\)). These are different from msat and mseq, which correspond to carbon inventories. Furthermore, we wish to emphasize that the behavior of mseq and \({\bar{\delta }}_{seq}\) is somewhat different due to the different equilibration times of DIC and δ13C33. We indicate the atmospheric δ13C as \({\bar{\delta }}_{a}\).

Isotopic fractionation is associated with air-sea gas exchange and with photosynthesis. The δ13C difference between the saturated carbon and the atmosphere, \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}={\bar{\delta }}_{o,sat}-{\bar{\delta }}_{a}\), is given by the equilibrated air-sea fractionation (≃10‰)34. The δ13C difference between the saturated and the sequestered carbon, \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}={\bar{\delta }}_{o,sat}-{\bar{\delta }}_{o,seq}\), is determined by photosynthetic fractionation and by air-sea equilibration through the following mechanism. Water enriched in isotopically light regenerated carbon upwells in the Southern Ocean, giving rise to a disequilibrium between the atmosphere and the ocean surface both in terms of DIC and δ13C. DIC has a ~1 year air-sea equilibration time, which is similar to the residence time of water at the surface of the Southern Ocean. Therefore, the DIC disequilibrium is partly erased by air-sea gas exchange before the water is subducted. In contrast, δ13C has a significantly longer air-sea equilibration time (~10 years) than the surface residence time of water in the Southern Ocean. As a result, the δ13C disequilibrium is largely retained at subduction. This has a somewhat counterintuitive implication for the isotopic bookkeeping. Consider a water mass upwelling and subducting in the Southern Ocean. For this water mass, we can write a carbon isotopic budget: \({\delta }_{w}\simeq {\delta }_{w,sat}-\frac{{C}_{w,seq}}{{C}_{w,sat}}{\epsilon }_{w,seq}\). Here, δw is the δ13C value of the water mass, δw,sat is the saturated δ13C at the surface of the Southern Ocean, Cw,seq is the biologically sequestered carbon in the water mass, Cw,sat is the saturated DIC concentration at the surface of the Southern Ocean, and ϵw,seq is the δ13C difference between the saturated and sequestered DIC in the water mass. As the water mass travels along the surface of the Southern Ocean, δw remains approximately constant because of the long timescale for isotopic equilibration ( ~10 years). Furthermore, δw,sat (the saturated δ13C) is unaffected by air-sea gas exchange. However, air-sea gas exchange does lead to a decrease in the ratio of sequestered carbon to saturated DIC in the surface ocean (\(\frac{{C}_{w,seq}}{{C}_{w,sat}}\)). To maintain isotopic mass balance, ϵw,seq then has to increase along the path of the water parcel at the surface of the Southern Ocean. This isotopic offset enhanced by air-sea gas exchange is retained after the water mass is subducted and traveling through the deep ocean. As such, \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) is not a true fractionation, which is why we refer to it as the sequestered offset factor. In the “Methods” section, we use chemical and isotopic data to estimate that \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\simeq\) 40‰ during the Holocene.

The LGM-to-Holocene change in the ocean-atmosphere δ13C difference can now be divided into contributions from physical air-sea fractionation and from the sequestered carbon pool:

where \({\bar{\delta }}_{o}\) and \({\bar{\delta }}_{a}\) represent the average δ13C in the ocean and atmosphere respectively and the Δ operator represents the difference between the Holocene and LGM values. We take \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o}=0.32\pm\)0.10‰ (1-σ uncertainty)46 and \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{a}=0.10 \pm\)0.10‰ 47. Taking the LGM-to-Holocene change in average ocean temperature equal to 2.57 ± 0.24 °C48 and the pCO2 change equal to 90 ppmv35, we estimate \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}=-0.18\pm\)0.03‰ (see “Methods” section). Substituting these values in eq. (3), we then estimate:

To gain insight into what specific process drove this change, we make a first-order Taylor expansion of the terms in the parenthesis (see Methods for more details):

The prefactor of eq. (5) is undoubtedly positive, which implies that at least one of the three terms inside the second set of parentheses (\(\frac{\Delta {m}_{seq}}{{m}_{seq}}\), \(-\frac{\Delta m}{m}\), \(\frac{\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}}{\bar{{\epsilon }_{seq}}}\)) be negative. These terms represent relative changes: in the ocean’s sequestered component; in the ocean’s total carbon; and in the fractionation of sequestered carbon in the ocean. The detailed quantification of each term in eq. (5) is presented in the “Methods” section. Here we summarize the key results.

During deglaciation, carbon is transferred from the ocean to the atmosphere13,20,49. This decreases the total ocean carbon inventory, which means that the second term is positive. The Holocene-LGM difference in the sequestered isotopic offset (\(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\)) can be estimated by realizing that \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) is always larger than ~25‰ (the photosynthetic fractionation) and that the LGM value of \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) must have been lower than the Holocene value of ~40‰ for two main reasons. Firstly, the expanded sea-ice cover at the LGM would have led to an increase in the disequilibrium carbon. Secondly, \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) increases with the ratio of the equilibration times of δ13C and DIC. This ratio was likely smaller at the LGM than during the Holocene, as explained in the “Methods” section. Thus, we have lower and upper bounds of 0 and 15‰ for \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\), which represent unlikely extremes. \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}=0\)‰ requires air-sea gas exchange to be larger at the LGM, when taking into account that pCO2 was lower at LGM than during the Holocene. \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}=15\) requires the absence of any gas exchange in the Southern Ocean at the LGM. As we don’t have any further information about the probability distribution of \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\), we estimate \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\)=7.5 ± 7.5‰ (with the central values more likely than the extreme ones).

Using the Holocene values for \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\simeq 40\)‰, mseq ≃ 0.08 × 1018 mol, and m ≃ 3 × 1018 mol50, we then find:

Converting moles to petagrams, this amounts to a decrease of 1000 ± 600 Pg in biologically sequestered carbon for the Holocene compared to the LGM. Before equilibration of the ocean alkalinity budget through the process of carbonate compensation32, this implies a Holocene-LGM increase in pCO2 ≃ 65 ± 35 ppmv. After accounting for a change in ocean alkalinity associated with carbonate compensation, the change increases to pCO2 ≃ 75 ± 40 ppmv. Hence, the inferred pCO2 increase could be sufficient to explain the entire ~90 ppm glacial-interglacial difference (within uncertainty).

Mechanisms of biological carbon sequestration

What are the relative contributions of the regenerated and disequilibrium carbon to the LGM to Holocene difference in biologically sequestered carbon? We provide a detailed calculation in the “Methods” section and here summarize the key results. Consider δ13C near deep-water formation regions in the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean51. These waters start their journey at the surface with no regenerated carbon, accumulating regenerated carbon as they flow through the abyss. As a result, δ13C data near deep-water formation sites provide an estimate of the preformed δ13C of a water mass before it is altered by organic matter respiration. In contrast, the ocean-averaged δ13C includes the globally averaged impact of organic matter respiration. By subtracting the ocean-averaged preformed δ13C from the ocean-averaged δ13C, we infer the regenerated component.

We estimate the ocean-averaged preformed δ13C by summing the preformed δ13C of Northern- and Southern-sourced waters, weighted by their respective fractions of the global ocean volume. There has been debate about these water-mass fractions at the LGM52. Sharp vertical gradients in δ13C, Cd/Ca, and δ18O in the Atlantic at the LGM have been interpreted as evidence of a boundary between Northern- and Southern-sourced water at ~2000 m53,54,55. This would imply that Northern-sourced waters filled ~10% of the deep ocean at the LGM, compared to ~40% during the Holocene56. Paleo-reconstructions based on Neodymium isotopes instead suggest little change in the water-mass configuration between the LGM and the Holocene57,58. To account for this range of possible LGM water-mass configurations, we estimated the change in regenerated carbon for a range of fractional changes in Northern-sourced waters from the LGM to Holocene Δα between 0-30% shown in Fig. 3. We found that the estimated change in the regenerated carbon (Δmreg) becomes a progressively smaller fraction of the sequestered carbon (Δmseq) for increasing Δα.

Δα = 0 corresponds to no LGM to Holocene change in the water-mass configuration, whereas Δα = 0.3 corresponds to Northern-sourced water being confined to the upper 2000 m of the Atlantic at the Last Glacial Maximum. The shaded area indicates the 2-σ uncertainty interval of the estimate. Source data and the Matlab code to generate this figure are provided as Source Data files in the online Supplementary Material.

Δα = 0 corresponds to the limit of no LGM to Holocene change in the water-mass configuration. In this limit, the regenerated component accounts for between −20% and +110% (2-σ uncertainty) of the sequestered carbon change, with a most likely value of +50%. In other words, our analysis is inconclusive about the contribution of regenerated carbon to the change in sequestered carbon in this regime. Δα = 0.3 instead corresponds to the limit of Northern-sourced water being confined to the upper 2000 m of the Atlantic at the LGM. In this limit, the regenerated component accounts for between −40% and +50% (2-σ uncertainty) of the sequestered carbon change, with a most likely value of +7%. In other words, regenerated carbon accounts for no more than half of the change in sequestered carbon in this regime.

While both Δα limits have some support in paleo-proxy data, they imply very different ocean circulations and biological disequilibrium at the LGM. Ocean dynamics suggest that if the volume occupied by Northern-sourced waters did not change (Δα = 0), then the overturning strength would likely not have changed appreciably either59,60. Furthermore, simulations have suggested that with the current overturning circulation, increased sea-ice coverage increases disequilibrium DIC by only a modest amount12. Therefore, changes in ocean carbon storage would indeed have to be associated with Δmreg rather than Δmseq, consistent with our analysis. The Δα = 0.3 limit implies a contraction of the volume of Northern-sourced waters at the LGM, which could have been forced by the expanded sea ice43. The expanded sea ice over the expanded Southern overturning cell could have provided an effective blocking of air-sea gas exchange. This would in turn be consistent with our inference that the change in sequestered carbon was mostly due to the disequilibrium component in this limit. In the next section we argue that independent Δ14C and oxygen proxy data are consistent with the second limit, but not the first.

Discussion

Our carbon isotopic mass budget suggests that the increase in atmospheric CO2 from the LGM to the Holocene was driven by a decrease in biologically sequestered carbon in the ocean. This calculation used the assumption that the biologically mediated difference in δ13C between the atmosphere and the surface of the Southern Ocean was either comparable or smaller at the LGM than during the Holocene. Thus, the Southern Ocean carbon must have been similarly or more poorly equilibrated with the atmosphere at the LGM compared to the Holocene. This seems plausible in view of the documented expansion of Antarctic sea ice61 and the expected strengthening of the overturning circulation in response to an increased surface buoyancy loss52 at the LGM. Should new evidence point to a weakened LGM overturning circulation, then our δ13C budget should also be revised. This said, the impact of the overturning strength on the δ13C and carbon budgets is likely relatively minor due to counteracting effects. For example, a stronger LGM circulation may not only decrease air-sea equilibration but also nutrient utilization, which would increase the disequilibrium.

Our δ13C-based estimate of the LGM to Holocene change in pCO2 before carbonate compensation (65 ± 35 ppmv) is in close agreement with estimates based on Δ14C (50 ± 27 ppmv62) and oxygen (64 ± 28 ppmv27). A key assumption underlying the use of Δ14C to infer changes in sequestered carbon is that export production rates have been approximately constant. The similarity between the estimate based on Δ14C and those based on δ13C suggests that this assumption is justified. Constant export production is in turn consistent with most of the change in biologically sequestered carbon being due to DIC disequilibrium. Thus, the Δα = 0.3 regime (Northern-sourced water confined to upper 2000 m of Atlantic at LGM) provides the most internally consistent picture. The consistency between the oxygen- and δ13C-based estimate is significant as well because the two proxies suffer from opposite biases. Consider the schematics in Fig. 2, which depict the role of the modern oceanic overturning circulation in regulating the air-sea fluxes of CO2, oxygen, and δ13C. Water upwelling in the Southern Ocean is not in equilibrium with the atmosphere. Due to organic matter respiration, it is undersaturated in oxygen, oversaturated in DIC, and its δ13C is below its saturated value. Once at the surface, the water spends about 1 year in contact with the atmosphere before being resubducted. This time is comparable to the air-sea equilibration timescale for CO232, but much longer than that of oxygen (~1 month32) and much shorter than that of δ13C (~10 years). Thus, the deviation from equilibrium in newly formed deep water is smaller for oxygen than for carbon, while the opposite it true for δ13C. As a result, the total biologically sequestered carbon may be underestimated by oxygen utilization and overestimated by δ13C. The agreement between the oxygen- and δ13C-based estimates can be explained with a reduction in Southern Ocean air-sea gas exchange at the LGM compared to the Holocene. If air-sea fluxes were indeed inhibited at the LGM, not only the disequilibrium in δ13C and carbon but also the disequilibrium in oxygen would have been largely retained at resubduction. Under this scenario, oxygen utilization more closely represents the total biologically sequestered carbon reservoir, as estimated from δ13C, rather than the regenerated carbon alone. We estimate (see “Methods” section) that this would imply a Holocene-LGM difference in global ocean average disequilibrium oxygen \(\Delta {\bar{O}}_{2,dis}\simeq\)–80 ± 50 μM. This is broadly consistent with the results from a recent modeling experiment (see Fig. 8B, C in ref. 42). Indeed, proxy data suggest decreased Southern Ocean air-sea gas exchange at the LGM compared to the Holocene63,64.

Our δ13C-based estimate of the LGM-to-Holocene change in biologically sequestered carbon in the ocean translates into a pCO2 change of 75 ± 40 ppmv after carbonate compensation. This could explain the entire Holocene-LGM difference, since the observed 90 ppmv lies within the estimated uncertainty interval. That said, it is also possible that biologically sequestered carbon in the ocean does not account for the full 90 ppmv of CO2 change. Given the good correspondence between the estimates based on O2 and δ13C, any remaining unexplained CO2 change would likely be due to a factor that has minimal impacts on either quantity. One such factor is whole-ocean alkalinity, which was likely higher at the LGM65,66 and would thus have generated a further decrease of atmospheric CO267,68. However, the magnitude of this effect is difficult to quantify as we lack direct paleo-proxies for alkalinity.

The main contribution of our work is to provide data-based constraints on the LGM carbon and δ13C budgets that have primarily been studied through the lense of numerical simulations5,11,12,69,70,71,72,73. Simulations rely on assumptions in the model formulations, for example with respect to changes in air-sea gas exchange and carbon export. Our data-based calculations suggest that differences in Southern Ocean carbon disequilibrium played a major role in glacial-interglacial CO2 changes, which narrows down the range of potential processes. We hope that the constraints emerging from our analysis provide a useful test for coupled models of global climate and the carbon cycle. Ultimately, this should improve model predictions of changes in the carbon cycle in both paleo and modern contexts.

Methods

In this Section, we derive the carbon budget that we used in the main text to infer the changes in atmospheric carbon between the LGM and Holocene. More specifically, we first estimate the Holocene-LGM difference in mseq and its impact on atmospheric pCO2 (Section “Sequestered carbon mass budget”). To estimate the individual contributions from mdis and mreg toward mseq, we calculate the Holocene-LGM mreg difference in Section “Regenerated carbon budget”. In Section “Dependence of equilibrated air-sea isotopic fractionation on atmospheric CO2”, we focus on the impact of atmospheric CO2 on the air-sea isotopic fractionation. Table 1 provides a list of key quantities used in these calculations.

Sequestered carbon mass budget

To formulate our carbon isotope mass budgets, we introduce the mass-averaged ocean δ13C:

For our sequestered carbon mass budget, we divide the integral in eq. (7) into saturated and sequestered carbon components:

where \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,seq}\) and \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,sat}\) are the respective mass-averaged δ13C values. Since our goal is to compare the changes in ocean \({\bar{\delta }}_{o}\) to those in the atmosphere, \({\bar{\delta }}_{a}\), we focus on the difference

The first term in brackets on the right-hand side of eq. (9) equals the physical fractionation between the atmosphere and the saturated carbon \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}\) (≃10‰):

We define the second bracketed term in eq. (9) as the sequestered isotopic offset factor \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\):

Combining eqs. ((9)–(11)) yields:

For the Holocene, we have sufficient data for a rough estimate of \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\). First, consider that \({\bar{\delta }}_{o}\simeq 0.5\)‰ 74, \({\bar{\delta }}_{a}\simeq -6.3\)‰36, \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}\simeq 10\)‰34 (assuming a mean ocean temperature of 3 °C). Furthermore, the mean ocean DIC concentration \(\bar{C}=2.30\) mol m−321 and the mean ocean DIC concentration \({\bar{C}}_{sat}=2.12\) mol m−3 (at 3 °C)75, which gives \({\bar{C}}_{seq}=\bar{C}-{\bar{C}}_{sat}=0.18\) mol m−3 and thus \(\frac{{m}_{seq}}{m}=\frac{\bar{{C}_{seq}}}{\bar{C}}=\frac{0.18}{2.30} \,\). Substituting these values into eq. (12) and rearranging, we obtain \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\simeq 40\)‰.

To indicate differences between Holocene minus LGM values we introduce the symbol Δ, e.g., \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o}={\bar{\delta }}_{o}^{{{\rm{Holo}}}}-{\bar{\delta }}_{o}^{{{\rm{LGM}}}}\). The budget in (12) then gives:

with \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o}\simeq 0.32\pm 0.10\)‰ (1-σ uncertainty)46 and \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{a}\simeq 0.10\pm 0.10\)‰47. Eq. (13) thus implies that \(\Delta \left(\frac{{m}_{seq}}{m}{\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\right)\simeq \Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}-0.22\pm 0.22\)‰. \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}\) can be expanded into contributions from changes in temperature and pCO2:

Given that \(\frac{\partial {\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}}{\partial T}\simeq -0.105\)‰ °C−134, \(\Delta \bar{T}=2.57\pm 0.2{4}\)°C48, \(\frac{\partial {\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}}{\partial {{{\rm{pCO}}}}_{2}}\simeq 0.001\)‰ ppmv−1 (see Section “Dependence of equilibrated air-sea isotopic fractionation on atmospheric CO2” below), and ΔpCO2 ≃ 90 ppmv, we obtain \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{d}\simeq -0.18\pm 0.03\)‰. Therefore, we conclude that:

Expanding this yields:

We proceed to estimate changes in sequestered carbon, Δmseq, directly. Rearranging eq. (16) gives:

Using the same values as above, we obtain for the prefactor: \(\left({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\frac{{m}_{seq}}{m}\right)\simeq 40\times \frac{0.18}{2.30}\simeq 3.1\). We estimate changes in total ocean carbon, Δm, by summing the estimated −0.016 × 1018 mol carbon transferred from the ocean to the atmosphere35 with the −850 ± 400 Gt = −(0.07 ± 0.03) × 1018 mol carbon transferred from the ocean to the terrestrial biosphere17. We find that Δm ≃ −(0.09 ± 0.03) × 1018 mol where the negative sign is consistent with carbon leaving the ocean after the LGM. With m ≃ 3 × 1018 mol for the Holocene50, we find the ratio \(\frac{\Delta m}{m}\simeq -0.03\pm 0.01\).

Now, we estimate changes in the sequestered isotopic offset factor \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\). As discussed earlier, decreased air-sea gas exchange would have decreased \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) at the LGM. Furthermore, the lower pCO2 at the LGM would have increased the equilibration time of δ13C, which would have decreased \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) further. Finally, \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) increases with the ratio of the equilibration times of δ13C and DIC. This ratio is proportional to the Revelle buffer factor \(B=\frac{\partial {{{\rm{lnpCO}}}}_{2}}{\partial {{\rm{\ln }}}{C}_{w,sat}}\)33. Previously, we showed that \(B\simeq \frac{{C}_{w,sat}}{\frac{[{{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}]}{O}+[{{{\rm{CO}}}}_{2}]}\simeq O\frac{{C}_{w,sat}}{[{{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}]}\) (with \(O=-\frac{\partial {{{\rm{lnpCO}}}}_{2}}{\partial {{\rm{\ln }}}[{{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}]}\simeq 1.4\))76. The buffer factor O is approximately constant and variations in Cw,sat are relatively minor, whereas [\({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\)] is close to inversely proportional to pCO2. Therefore, B would have been lower at the LGM than during the Holocene, which in turn implies a smaller ratio of the equilibration times of δ13C and DIC. Overall, it appears likely that \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) was lower at the LGM than during the Holocene. Therefore, we consider our Holocene estimate \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\approx \,40\)‰ to be an upper bound for the LGM. We also know that \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\) must have been at least as high as photosynthetic fractionation, \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{p}=25\)‰30, at the LGM. We thus obtain a range in sequestered isotopic offset changes, \(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\simeq\) 0–15‰, and a ratio estimate of \(\frac{\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}}{\bar{{\epsilon }_{seq}}}\simeq 0.2\pm 0.2\). Together, we find that \(\left({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\frac{{m}_{seq}}{m}\right)\left(\frac{\Delta m}{m}-\frac{\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}}{\bar{{\epsilon }_{seq}}}\right)\simeq -0.7\pm 0.6\)‰ and thus:

Using m ≃ 3 × 1018 mol and \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{seq}\simeq 40\)‰, we find:

which amounts to a decrease of 1000 ± 600 Pg in sequestered carbon for the Holocene compared to the LGM. In terms of the average deep-ocean sequestered carbon concentration \({\bar{C}}_{seq}\), this is a change of \(\Delta {\bar{C}}_{seq}=\frac{\Delta {m}_{seq}}{V}\simeq -0.06\pm 0.03\) mol/m3 where we have used for the ocean volume V = 1.4 × 1018 m3.

We use the approach laid out in previous publications68,77 to estimate the increase in atmospheric CO2 induced by such a decrease in the sequestered carbon in the ocean. We begin by writing down the balance equation for carbon in the ocean-atmosphere system:

with M the CO2 content of the atmosphere (mol), V the volume of the ocean (m3), and Ioa the total carbon inventory of the ocean-atmosphere system (mol).

First, we consider the pCO2 change before the ocean ALK (A) budget has re-equilibrated through the carbonate compensation process32. In that case, the total carbon in the ocean-atmosphere system is conserved: ΔIoa = 0. Considering changes in the different carbon reservoirs, eq. (20) gives:

Expanding \({\bar{C}}_{sat}\) in terms of pCO2 and rearranging leads to:

with \(B\equiv \frac{\partial \ln {{{\rm{pCO}}}}_{2}}{\partial \ln {C}_{sat}}\) the Revelle buffer factor32. Using M = 1.8 × 1020 mol, V = 1.4 × 1018 m3, Csat = 2.3 mol m−3, pCO2 = 2.5 × 10−4 (250 ppmv), and B = 12, equation (22) reduces to:

With \(\Delta {\bar{C}}_{seq}\simeq -0.06\pm 0.03\) mol/m3, eq. (23), we then get the change in pCO2 before carbonate compensation:

The calculation becomes somewhat more complicated when changes in the total carbon inventory of the ocean-atmosphere system associated with carbonate compensation through dissolution and burial of CaCO3 are considered. In this case, \(\Delta {I}_{oa}=\frac{V\Delta \bar{A}}{2}\), because for every additional mole of carbon in CaCO3, the ocean gains two moles of ALK. To a good approximation, ALK can be approximated by the carbonate alkalinity, i.e., A ≃[\({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)] + 2[\({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\)]. Neglecting dissolved CO2, Csat + Cseq ≃ [\({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)] + [\({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\)] and \(\Delta ({C}_{sat}+{C}_{seq})\simeq \Delta\)[\({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)] + Δ[\({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\)]. Thus, \(\Delta \bar{A}\approx \Delta \left({\bar{C}}_{sat}+{\bar{C}}_{seq}\right)+\Delta \overline{[{{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}]}\). After full carbonate compensation, \(\Delta \overline{[{{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}]}\)=0, which means that

Furthermore, the ocean-atmosphere carbon budget can be written as:

The factor \(\frac{1}{2}\) reflects the very nature of the carbonate compensation process: for every CO2 molecule that the ocean takes up, the ocean also needs to take up a \({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\) ion from the sediment to restore the original \({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\) concentration. Changes in sequestered carbon lead to changes in ALK but not temperature and salinity. We therefore expand in terms of pCO2 and A:

with \({\gamma }_{A}\equiv \frac{\partial {C}_{sat}}{\partial A}\simeq 0.90\)78. Substituting the relationships (27) and (26) in eq. (25), we can solve for Δ pCO2:

Thus,

Again using ΔCseq ≃ −0.06 ± 0.03 mol/m3, eq. (29) gives:

Dependence of equilibrated air-sea isotopic fractionation on atmospheric CO2

With increasing atmospheric pCO2, the carbonate equilibrium shifts toward higher \({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and lower \({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\) concentrations. To estimate the impact of this chemical shift on the air-sea carbon isotope fractionation, we divide the average δ13C of the saturated carbon (\({\bar{\delta }}_{o,sat}\)) into contributions from \({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and \({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\):

with mHCO3 and mCO3 the saturated \({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and \({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\) inventories and \({\bar{\delta }}_{HCO3}\) and \({\bar{\delta }}_{CO3}\) the average δ13C of the saturated \({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and \({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\). Using msat ≃ mHCO3 + mCO3, we can rewrite eq. (31) as:

with \({\epsilon }_{HCO3,CO3}={\bar{\delta }}_{HCO3}-{\bar{\delta }}_{CO3}\) the average isotopic fractionation between \({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and \({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\). This in turn provides an expression for ϵd in terms of contributions from \({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and \({{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}\):

with \({\epsilon }_{HCO3,a}={\bar{\delta }}_{HCO3}-{\bar{\delta }}_{a}\) the average isotopic fractionation between the saturated \({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and the atmosphere. In this expression, the only quantity with a strong dependence on pCO2 is mCO3. Therefore, we can approximate:

which leads to:

with \(O\equiv -\frac{\partial {{{\rm{lnpCO}}}}_{2}}{\partial {{\rm{\ln }}}[{{{\rm{CO}}}}_{3}^{2-}]}\,\approx 1.4\)76. Using \(\frac{{m}_{CO3}}{{m}_{sat}}=0.1\), \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{HCO3,CO3}=3.5\)‰34, pCO2 = 250 ppmv, we finally obtain \(\frac{\partial {\epsilon }_{d}}{\partial {{{\rm{pCO}}}}_{2}}\simeq 0.001\)‰ ppmv−1.

Regenerated carbon budget

For this calculation, we divide the total carbon inventory into preformed and regenerated components. The preformed carbon is defined as the sum of the saturated and disequilibrium carbon. Isotopic bookkeeping analogous to eqs. (7) through (13) then gives:

where we used that \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{p}\,=\,{\bar{\delta }}_{o,reg}-{\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre}\) by definition. Eq. (36) can be rearranged as:

where we have neglected a potential Holocene-LGM difference in the average photosynthetic fractionation factor (\(\Delta {\bar{\epsilon }}_{p}\)), since such effects are thought to be small30. To estimate Δmreg, we use m = 3 × 1018 mol, \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{p}=-25\)‰30, \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o}=0.32\pm 0.10\)‰46, \(\Delta m=-\left(0.09\pm 0.03\right)\times 1{0}^{18}\) mol, i.e., the same values as in the previous calculations. Furthermore, we estimate \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre}\) based on measured Holocene and LGM δ13C in deep-water mass formation regions, as outlined below.

The surface Southern Ocean has low δ13C values due to upwelling of water rich in respired carbon. Much of this isotopically light signature is retained at subduction. As a result, deep waters formed in the Southern Ocean have lower δo,pre than deep waters sourced from the North Atlantic. Since these deep waters mix conservatively in the ocean interior, we divide \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre}\) into Northern- and Southern-sourced end-members:

with αHolo and αLGM the fractions of deep water from Northern sources during the Holocene and at the LGM. To estimate the preformed δ13C of Northern-sourced water for the LGM and Holocene (\({\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,N}^{Holo}\) and \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,N}^{LGM}\)), we use published benthic foraminifera δ13C from North Atlantic cores located at depths <2000 m. We use benthic foraminifera δ13C from Southern Ocean cores located at depths <2000 m to estimate the preformed δ13C of Southern-sourced water for the LGM and Holocene (\({\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,S}^{Holo}\) and \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,S}^{LGM}\)). We use the cores in which both LGM and Holocene δ13C have been measured to estimate the Holocene-LGM difference in preformed δ13C of Northern- and Southern-sourced waters (\(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,N}\) and \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,S}\)). From these data compilations (see online Supplementary Material), we find \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,N}^{Holo}=1.12\pm 0.06\)‰, \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,S}^{Holo}=0.9\pm 0.1\)‰, \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,N}^{LGM}=1.42\pm 0.05\)‰, \({\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,S}^{LGM}=0.6\pm 0.2\)‰, \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,N}=-0.30\pm 0.05\)‰, \(\Delta {\bar{\delta }}_{o,pre,S}=0.28\pm 0.16\)‰. Furthermore, we estimate for the Holocene Northern-sourced water-mass fraction αHolo = 0.40 ± 0.05 based on ref. 56. Now, we use these numbers and eqs. (37) and (38) to create Fig. 3.

Finally, we estimate the global average Holocene-LGM difference in disequilibrium oxygen (\(\Delta {\bar{O}}_{2,dis}\)) under the assumption that air-sea gas exchange in the Southern Ocean was completely inhibited at the LGM. Under this scenario, \(\Delta {\bar{O}}_{2,dis}\simeq \frac{\Delta {\bar{C}}_{dis}}{{R}_{C:{O}_{2}}}=\frac{\Delta {m}_{dis}}{V{R}_{C:{O}_{2}}}\) (with \(\Delta {\bar{C}}_{dis}\) the Holocene-LGM difference in the global average disequilibrium DIC concentration and \({R}_{C:{O}_{2}}\) the C:O2 Redfield ratio). Furthermore, Δα ≃ 0.3 under this scenario (see explanation in the main body of the text). Eqs. (37) and (38) then give \(\Delta {m}_{reg}=\left(-0.005\pm 0.019\right)\times 1{0}^{18}\) mol. Thus, \(\Delta {m}_{dis}=\Delta {m}_{seq}-\Delta {m}_{reg}=\left(-0.08\pm 0.05+0.005\pm 0.019\right)\times 1{0}^{18}\) mol = \(\left(-0.07\pm 0.05\right)\times 1{0}^{18}\) mol. Using V = 1.4 × 1018 m3 and \({R}_{C:{O}_{2}}=\) 117:17079, we obtain: \(\Delta {\bar{O}}_{2,dis}\simeq -0.08\pm 0.05\) mol/m3.

Data availability

This study did not generate any new primary data. The compilation of marine δ13C measurements (secondary data) used to estimate the LGM-to-Holocene change in regenerated carbon is provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file (SourceData.xlsx). There are no restrictions on the availability of these data. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The Matlab code with which Fig. 3 was generated is available as online Supplementary Material with this article (CalcRegC_d13C_new.m).

References

Petit, J. R. et al. Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica. Nature 399, 429–436 (1999).

Knox, F. & McElroy, M. Change in atmospheric CO2: influence of the marine biota at high latitude. J. Geophys. Res. 89, 4629–4637 (1984).

Sarmiento, J. L. & Toggweiler, J. R. A new model for the role of the oceans in determining atmospheric pCO2. Nature 308, 621–624 (1984).

Siegenthaler, U. & Wenk, T. Rapid atmospheric CO2 variations and ocean circulation. Nature 308, 624–626 (1984).

Heinze, C., Maier-Reimer, E. & Winn, K. Glacial pCO2 reduction by the World Ocean: experiments with the Hamburg carbon cycle model. Paleoceanography 6, 395–430 (1991).

Bacastow, R. B. The effect of temperature change of the warm surface waters of the oceans on atmospheric CO2. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 10, 319–334 (1996).

Archer, D. E. et al. Atmospheric pCO2 sensitivity to the biological pump in the ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 1219–1230 (2000).

Toggweiler, J. R., Gnanadesikan, A., Carson, S., Murnane, R. & Sarmiento, J. L. Representation of the carbon cycle in box models and GCMs 1. Solubility pump. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1027 (2003).

Brovkin, V., Ganopolski, A., Archer, D. E. & Rahmstorf, S. Lowering of glacial atmospheric CO2 in response to changes in oceanic circulation and marine biogeochemistry. Paleoceanography 22, PA4202 (2007).

Brovkin, V., Ganopolski, A., Archer, D. E. & Munhoven, G. Glacial CO2 cycle as a succession of key physical and biogeochemical processes. Climate 8, 251–264 (2012).

Lauderdale, J. M., Naveira Garabato, A. C., Oliver, K. I. C., Follows, M. J. & Williams, R. G. Wind-driven changes in Southern Ocean residual circulation, ocean carbon reservoirs and atmospheric CO2. Clim. Dyn. 41, 2145–2164 (2013).

Khatiwala, S., Schmittner, A. & Muglia, J. Air-sea disequilibrium enhances ocean carbon storage during glacial periods. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw4981 (2019).

Galbraith, E. D. & Skinner, L. C. The biological pump during the Last Glacial Maximum. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 12, 559–586 (2020).

Lhardy, F. et al. A first intercomparison of the simulated LGM carbon results within PMIP-Carbon: role of the ocean boundary conditions. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatology 36, e2021PA004302 (2021).

Ciais, P. et al. Large inert carbon pool in the terrestrial biosphere during the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Geosci. 5, 74–79 (2012).

Oishi, R. & Abe-Ouchi, A. Influence of dynamic vegetation on climate change and terrestrial carbon storage in the Last Glacial Maximum. Climate 9, 1571–1587 (2013).

Jeltsch-Thömmes, A., Battaglia, G., Cartapanis, O., Jaccard, S. L. & Joos, F. Low terrestrial carbon storage at the Last Glacial Maximum: Constraints from multi-proxy data. Climate 15, 849–879 (2019).

Davies-Barnard, T., Ridgwell, A., Singarayer, J. & Valdes, P. Quantifying the influence of the terrestrial biosphere on glacial-interglacial climate dynamics. Climate 13, 1381–1401 (2017).

Omta, A. W., Dutkiewicz, S. & Follows, M. J. Dependence of the ocean-atmosphere partitioning of carbon on temperature and alkalinity. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 25, GB1003 (2011).

Sigman, D. M. & Boyle, E. A. Glacial-interglacial variations in atmospheric carbon dioxide. Nature 407, 859–869 (2000).

Volk, T. & Hoffert, M. I. Ocean carbon pumps: analysis of relative strengths and efficiencies in ocean-driven atmospheric CO2. In The Carbon Cycle and Atmospheric CO2: Natural variations Archean to Present, pages (eds. Sundquist, E. T. & Broecker, W. S.) 99–110 (AGU, 1985).

Marinov, I., Follows, M. J., Gnanadesikan, A., Sarmiento, J. L. & Slater, R. D. How does ocean biology affect atmospheric pCO2? Theory and models. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 113, C07032 (2008).

Toggweiler, J. R., Murnane, R., Carson, S. R., Gnanadesikan, A. & Sarmiento, J. L. Representation of the carbon cycle in box models and GCMs 2. Organic pump. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1027 (2003).

Goodwin, P. & Lauderdale, J. M. Carbonate ion concentrations, ocean carbon storage, and atmospheric CO2. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 882–893 (2013).

Hoogakker, B. A., Elderfield, H., Schmiedl, G., McCave, I. N. & Rickaby, R. E. M. Glacial-interglacial changes in bottom-water oxygen content on the Portuguese margin. Nat. Geosci. 8, 40–43 (2015).

Jacobel, A. W. et al. Deep Pacific storage of respired carbon during the last ice age: perspectives from bottom water oxygen reconstructions. Quat. Sci. Rev. 230, 106065 (2020).

Vollmer, T. D., Ito, T. & Lynch-Stieglitz, J. Proxy-based preformed phosphate estimates point to increased biological pump efficiency as primary cause of Last Glacial Maximum CO2 drawdown. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatology 37, e2021PA004339 (2022).

Broecker, W. S. Glacial to interglacial changes in ocean chemistry. Prog. Oceanogr. 11, 151–197 (1982).

Shackleton, N. J., Hall, M. A., Line, J. & Shuxi, C. Carbon isotope data in core V19–30 confirm reduced carbon dioxide concentration in the Ice Age atmosphere. Nature 306, 319–322 (1983).

Broecker, W. S. & McGee, D. The 13C record for atmospheric CO2: what is it trying to tell us? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 368, 175–182 (2013).

Peterson, C. D. & Lisiecki, L. E. Deglacial carbon cycle changes observed in a compilation of 127 benthic δ13C time series (20–6 ka). Climate 14, 1229–1252 (2018).

Broecker, W. S. & Peng, T. H. Tracers in the Sea (Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory, 1982).

Galbraith, E. D., Kwon, E. Y., Bianchi, D., Hain, M. P. & Sarmiento, J. L. The impact of atmospheric pCO2 on carbon isotope ratios of the atmosphere and ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 307–324 (2015).

Zhang, J., Quay, P. D. & Wilbur, D. O. Carbon isotope fractionation during gas-water exchange and dissolution of CO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 107–114 (1995).

Bereiter, B. et al. Revision of the EPICA Dome C CO2 record from 800 to 600 kyr before present. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 542–549 (2015).

Schmitt, J. et al. Carbon isotope constraints of the deglacial CO2 rise from ice cores. Science 336, 711–714 (2012).

Zeebe, R. E. & Wolf-Gladrow, D. A. CO2 in Seawater: Equilibrium, Kinetics, Isotopes (Elsevier, 2001).

Bauska, T. K. et al. Carbon isotopes characterize rapid changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide during the last deglaciation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3465–3470 (2016).

Köhler, P., Knorr, G. & Bard, E. Permafrost thawing as a possible source of abrupt carbon release at the onset of the Bølling/Allerød. Nat. Commun. 5, 5520 (2014).

Wu, J. J. et al. Deglacial release of petrogenic and permafrost carbon from the Canadian Arctic impacting the carbon cycle. Nat. Commun. 13, 7172 (2019).

Williams, R. G. & Follows, M. J. Ocean Dynamics and the Carbon Cycle (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Eggleston, S. & Galbraith, E. D. The devil’s in the disequilibrium: multi-component analysis of dissolved carbon and oxygen changes under a broad range of forcings in a general circulation model. Biogeosciences 15, 3761–3777 (2018).

Ferrari, R. et al. Antarctic sea ice control on ocean circulation in present and glacial climates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 8753–8758 (2014).

Ito, T. & Follows, M. J. Air-sea disequilibrium of carbon dioxide enhances the biological carbon sequestration in the Southern Ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 1129–1138 (2013).

Skinner, L. C. & Bard, E. Radiocarbon as a dating tool and tracer in paleoceanography. Rev. Geophys. 60, e2020RG000720 (2022).

Gebbie, G., Peterson, C. D., Lisiecki, L. E. & Spero, H. J. Global-mean marine δ13C and its uncertainty in a glacial state estimate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 125, 144–159 (2015).

Eggleston, S., Schmitt, J., Bereiter, B., Schneider, R. & Fischer, H. Evolution of the stable carbon isotope composition of atmospheric CO2 over the last glacial cycle. Paleoceanography 31, 434–452 (2016).

Bereiter, B., Shackleton, S., Baggenstos, D., Kawamura, K. & Severinghaus, J. Mean global ocean temperatures during the last glacial transition. Nature 553, 39–44 (2018).

Peacock, S., Lane, E. & Restrepo, J. M. A possible sequence of events for the generalized glacial-interglacial cycle. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 20, GB2010 (2006).

Watson, A. J. & Orr, J. C. Carbon dioxide fluxes in the global ocean. In Ocean Biogeochemistry (ed. Fasham, M. J. R.) 123–143 (Springer, 2003).

Duplessy, J. C. et al. Deepwater source variations during the last climatic cycle and their impact on the global deepwater circulation. Paleoceanography 3, 343–360 (1988).

Pavia, F. J., Jones, C. S. & Hines, S. K. Geometry of the meridional overturning circulation at the Last Glacial Maximum. J. Clim. 35, 5465–5482 (2022).

Curry, W. B. & Oppo, D. W. Glacial water mass geometry and the distribution of δ13C of ΣCO2 in the western Atlantic Ocean. Paleoceanography 20, PA1017 (2005).

Marchitto, T. M. & Broecker, W. S. Deep water mass geometry in the glacial Atlantic Ocean: a review of constraints from the paleonutrient proxy Cd/Ca. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 7, 12 (2006).

Lund, D. C., Adkins, J. F. & Ferrari, R. Abyssal Atlantic circulation during the Last Glacial Maximum: constraining the ratio between transport and vertical mixing. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatology 26, PA1213 (2011).

Gebbie, G. & Huybers, P. J. Total matrix intercomparison: a method for determining the geometry of water-mass pathways. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 40, 1710–1728 (2010).

Du, J., Haley, B. A. & Mix, A. C. Evolution of the global overturning circulation since the Last Glacial Maximum based on marine authigenic neodymium isotopes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 241, 106396 (2020).

Pöppelmeier, F. et al. Northern-sourced water dominated the Atlantic Ocean during the Last Glacial Maximum. Geology 48, 826–829 (2020).

Gnanadesikan, A. A simple predictive model for the structure of the oceanic pycnocline. Science 283, 2077–2079 (1999).

Nayak, M. S., Bonan, D. B., Newsom, E. R. & Thompson, A. F. Controls on the strength and structure of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation in climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109055 (2024).

Crosta, X. et al. Antarctic sea ice over the past 130,000 years—Part 1: a review of what proxy records tell us. Climate 18, 1729–1756 (2022).

Skinner, L. C. et al. Rejuvenating the ocean: mean ocean radiocarbon, CO2 release, and radiocarbon budget closure across the last deglaciation. Climate 19, 2177–2202 (2023).

Gottschalk, J. et al. Biological and physical controls in the Southern Ocean on past millennial-scale atmospheric CO2 changes. Nat. Commun. 7, 11539 (2016).

Skinner, L. C. et al. Radiocarbon constraints on the glacial ocean circulation and its impact on atmospheric CO2. Nat. Commun. 8, 16010 (2017).

Cartapanis, O., Galbraith, E. D., Bianchi, D. & Jaccard, S. L. Carbon burial in deep-sea sediment and implications for oceanic inventories of carbon and alkalinity over the last glacial cycle. Climate 14, 1819–1850 (2018).

Weinans, E., Omta, A. W., van Voorn, G. A. K. & van Nes, E. H. A potential feedback loop underlying glacial interglacial cycles. Clim. Dyn. 57, 523–535 (2021).

Omta, A. W., van Voorn, G. A. K., Rickaby, R. E. M. & Follows, M. J. On the potential role of marine calcifiers in glacial-interglacial dynamics. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 692–704 (2013).

Omta, A. W., Ferrari, R. & McGee, D. An analytical framework for the steady-state impact of carbonate compensation on atmospheric CO2. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 720–735 (2018).

Broecker, W. S. et al. How strong is the Harvardton-Bear constraint? Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 13, 817–820 (1999).

Bouttes, N., Paillard, D., Roche, D. M., Brovkin, V. & Bopp, L. Last Glacial Maximum CO2 and δC-13 successfully reconciled. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L02705 (2011).

Morée, A. L., Schwinger, J. & Heinze, C. Southern Ocean controls of the vertical marine δ13C gradient—a modelling study. Biogeosciences 15, 7205–7223 (2018).

Morée, A. L. et al. Evaluating the biological pump efficiency of the Last Glacial Maximum ocean using δ13C. Climate 17, 753–774 (2021).

Stein, K., Timmermann, A., Kwon, E. Y. & Friedrich, T. Timing and magnitude of Southern Ocean sea ice/carbon cycle feedbacks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 4498–4504 (2020).

Peterson, C. D., Lisiecki, L. E. & Stern, J. V. Deglacial whole-ocean δ13C change estimated from 480 benthic foraminiferal records. Paleoceanography 29, 549–563 (2014).

Follows, M. J., Ito, T. & Dutkiewicz, S. On the solution of the carbonate system in biogeochemistry models. Ocean Model. 12, 290–301 (2006).

Omta, A. W., Goodwin, P. & Follows, M. J. Multiple regimes of air-sea carbon partitioning identified from constant-alkalinity buffer factors. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 24, GB3008 (2010).

Ito, T. & Follows, M. J. Preformed phosphate, soft-tissue pump and atmospheric CO2. J. Mar. Res. 63, 813–839 (2005).

Goodwin, P. & Lenton, T. M. Quantifying the feedback between ocean heating and CO2 solubility as an equivalent carbon emission. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L15609 (2009).

Lenton, T. M. & Watson, A. J. Redfield revisited: 1. Regulation of nitrate, phosphate, and oxygen in the ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 225–248 (2000).

Acknowledgements

A.W.O., C.L.F., and J.M.L. are grateful for support from the Simons Collaboration on Computational Biogeochemical Modeling of Marine Ecosystems/CBIOMES (Grant IDs: 549931, MJF; 553242, C.L.F.; 827829, C.L.F.). R.F. is grateful for support through NSF award AGS-1835576. The authors would like to thank Mick Follows, Steph Dutkiewicz, Kat Allen, David McGee, Ed Boyle, and Lorraine Lisiecki for their helpful comments and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W.O.: conceptualization, analysis, writing initial draft, editing; C.L.F.: conceptualization, analysis, writing initial draft, editing; J.M.L.: analysis, editing; R.F.: conceptualization, analysis, editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lorraine Lisiecki and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Omta, A.W., Follett, C.L., Lauderdale, J.M. et al. Carbon isotope budget indicates biological disequilibrium dominated ocean carbon storage at the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat Commun 15, 8006 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52360-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52360-z