Abstract

When reflected from an interface, a laser beam generally drifts and tilts away from the path predicted by ray optics, an intriguing consequence of its finite transverse extent. For twisted light, such beam shifts manifest even more dramatically: upon reflection, a field containing a high-order optical vortex is expected to experience not only geometrical shifts, but an additional splitting of its high-order vortex into a constellation of unit-charge vortices, a phenomenon known as topological aberration. In this article, we report on the experimental observation of the topological aberration effect, verified through the deformation of vortex constellations upon reflection. We develop a general theoretical framework to study topological aberrations in terms of the elementary symmetric polynomials of the coordinates of a vortex constellation, a mathematical abstraction which we prove to be the physical quantity of practical interest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The reflection of light beams on interfaces is a quintessential problem in wave optics. In contrast to simple geometrical optics laws, where a ray of light reflects of a surface with the same incidence angle but on the opposing side of the surface normal, the reflection of beams in wave optics encompasses a more complex behaviour. Generally, a beam can be mathematically described by a finite spectrum of plane waves. Upon reflection, each of these plane waves individually follows paths determined by geometrical optics1. However, the changes to the amplitudes and phases of the component plane waves result in a reflected field which is macroscopically different from the incident field. Perhaps the most well-known examples of such phenomena are optical beam shifts, which are spatial and angular deviations of reflected laser beams from their expected ray-optical trajectories2,3. Such shifts are usually separated into Goos-Hänchen (GH)4,5 and Imbert-Fedorov (IF)2,6 shifts, which occur along and orthogonal to the plane of incidence, respectively. These effects have distinct physical origins: while the GH shifts come from the angular variation of the reflection coefficient of the interface, the IF shifts, also known as the spin-Hall effect of light7, stem from the rotation of the plane of incidence experienced by elliptically polarised waves upon reflection. The GH and IF shifts have been extensively studied for different types of optical beams and interfaces in a range of contexts, as discussed in detail in Ref. 2.

A more subtle topic is the reflection of vortex beams2,8,9,10,11,12,13. Such beams are most well known for their ability to carry orbital angular momentum (OAM), which is accompanied by a twisted phase structure, i.e., a varying phase front transverse to the propagation direction as \(\exp (i\ell \phi )\), where ℓ is an integer number and ϕ labels the azimuthal angle14,15. The wavefronts of such beams consist of ∣ℓ∣ identical helicoids nested on the propagation axis, on which lies a strength-ℓ optical vortex or phase singularity16,17. Due to the OAM-induced mixing of the spatial and angular GH and IF shifts18, vortex beams also acquire OAM sidebands upon reflection19 and feature significant deformations in their intensity profiles8,9 at critical angles. Beyond beam shifts, Dennis and Götte showed in their seminal work20 that a pure strength-ℓ optical vortex splits into a constellation of unit strength vortices by reflecting at a simple dielectric interface, which they recognised as a topological aberration effect. It is well known, however, that it is impossible to generate perfect higher-order vortices, as the latter are unstable under any kind of pertubation21,22,23. Therefore, a fundamental question remains open: how do vortex constellations, the actual observable physical objects, experience topological aberrations?

In this article, we address this question first by generalising the framework developed in Ref. 20 to arbitrary uniform aberrations of vortex constellations, thereby addressing typical experimental limitations in the generation of vortex beams. We then show that the aberration of a vortex constellation is captured by a linear transformation of the elementary symmetric polynomials of its coordinates, and that this transformation is related to the angular Wirtinger derivatives of the aberration. Lastly, we detail the experimental observation of the topological aberration of vortex constellations under total internal reflection from a thin Au film-Fused Silica interface, where aberration effects are enhanced due to the resonant excitation of surface plasmons at the interface. With this method, we are able to verify the topological aberration using constellations with up to 3 vortices, in good agreement with the theoretical model developed. Due to the direct link between the vortex dynamics and the properties of the material upon which the light is reflected, our results could be applied to advanced material characterisation techniques. Moreover, the underlying theoretical description of the vortex dynamics might also be applicable to other fields of physics such as Bose–Einstein condensates24,25, superfuilds26,27, or topological field theories28.

Results and Discussion

Theory of topological aberrations

We start by considering an arbitrary input field containing a constellation of ℓm identical unit-strength vortices. In momentum space, the scalar part of such a field can be written as20

where χ = (χ, χ*), with \(\chi=({k}_{x}+i{k}_{y})/\sqrt{2}\), and (kx, ky) are Cartesian coordinates in momentum space. \(\sqrt{2}| \chi |={k}_{\perp }=\sqrt{{k}_{x}^{2}+{k}_{y}^{2}}\) and \({{{\rm{Arg}}}}(\chi )=\alpha={\tan }^{-1}({k}_{y}/{k}_{x})\), where k⊥ and α are the momentum radial and azimuthal coordinates, respectively. Equation (1) can be seen as a superposition of optical vortices with topological charges 0 ≤ ℓ ≤ ℓm, whose background functions σℓ(∣χ∣) determine both the OAM spectrum and the field’s radial features. Furthermore, the constellation coordinates are encoded in the complex roots of the field (1), which is a polynomial of order ℓm in χ.

A field of the form given in Eq. (1), i.e. a constellation of vortices, is naturally obtained by attempting to generate a vortex of order ℓm experimentally, due to inherent limitations in light-shaping devices and/or subsequent aberrations caused by mirrors, lenses, and other refractive elements. Nevertheless, for small aberrations, which is the case for a carefully assembled experiment, the contributions of ℓ < ℓm are small and the constellation is tightly confined to the beam’s central propagation direction. In this case, we can approximate the field in Eq. (1) in real space to the lowest order of each OAM component, obtaining

where ξ = (ξ, ξ*), with \(\xi=(x+iy)/\sqrt{2}\), and where (x, y) are the Cartesian coordinates in real space. This approximation is valid when the lowest order in the power expansion of σℓ(∣χ∣) is zero, which is the case for Gaussian background fields, for example. However, the approximation breaks when the background fields have components of high-order radial modes, in which case more complicated constellations with both positively and negatively charged vortices may appear29,30. A detailed derivation of the coefficients \({\bar{\sigma }}_{\ell }\) is provided in the Supplementary note 131.

Upon a spatially uniform aberration such as the reflection from a flat interface, each plane wave component of momentum χ in the angular spectrum (1) is transformed as \(\exp (i{{{\boldsymbol{\chi }}}}\cdot {{{{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}}}^{*})\to \,R({{{\boldsymbol{\chi }}}})\exp (i{{{\boldsymbol{\chi }}}}\cdot {{{{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}}}^{*})\), where R(χ) is the momentum-dependent aberration function. In the case of reflection from a flat interface, the aberration function is the reflection coefficient given by the Fresnel coefficients, which also depends on the incident and measurement polarisations2,20. The resulting field in real space can then be modelled as

which is a Fourier transform in the complex coordinates ξ and χ. Hence, we can expand the aberration in a power series and use the differentiation property of the Fourier transform (FT), which maps the FT of \({\chi }^{m}{\chi }^{*n-m}{\tilde{\psi }}_{I}({{{\boldsymbol{\chi }}}})\) to the n-th order derivatives of ψI(ξ). We obtain

where \(\partial /\partial \xi \,=\, \left(\partial /\partial x-i\partial /\partial y\right)/\sqrt{2}\) and \(\partial /\partial \chi \,=\, \left(\partial /\partial {k}_{x}-i\partial /\partial {k}_{y}\right)/\sqrt{2}\) are Wirtinger derivatives32. From Eqs. (2) and (4), we arrive at the final expression for the aberrated field

where \({\bar{\gamma }}_{\ell }\) are the coefficients of the vortex expansion of the aberrated field, derived in detail in the Supplementary note 131.

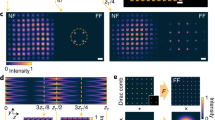

Equation (6) shows that an aberration decomposes the incoming light field into a superposition of its Wirtinger derivatives, weighted by the Wirtinger derivatives of the aberration function. Interestingly, in the case of the vortex input field of Eq. (1) the derivative modes are simply optical vortices of lower order, in such a way that the aberrated field still contains a collection of ℓm phase singularities, but in a deformed constellation, as we illustrate in Fig. 1. This implies that by monitoring the changes in a vortex constellation, one can gain insight into the properties of the aberration function, and thus into features of the light-matter interaction causing the aberration.

The figure shows the input and reflected fields of a second-order vortex constellation as measured in our experiment. k denotes a plane wave component of the incident vortex, while k0 is the central wave vector in the beam. The plane of incidence is kxkz, and the dashed lines show the ray optics trajectory of the central plane wave k0, with the angle of incidence θ0. The input and reflected constellations are marked with black crosses and orange circles, respectively. The intensity scaling does not apply to the magnified regions.

High-order aberrations of vortex constellations

Equation (6) establishes a direct correspondence between the coefficients of the vortex expansions of the incident and aberrated fields. However, the question still remains as to how the coordinates of the singularities within the corresponding constellations compare with one another. This problem is elegantly solved by Vieta’s theorem33, which we illustrate in the following. Consider an arbitrary constellation of ℓm vortices with coordinates (xj, yj), which yields a vortex expansion with roots \({\Delta }_{j}=({x}_{j}+i{y}_{j})/\sqrt{2}\) and coefficients ci to be determined. According to Vieta’s theorem we have that

where ej is the j-th order elementary symmetric polynomial (ESP) of the set of complex roots {Δ}. In terms of ESPs, equation (6) assumes the simple form

where the vectors eI and eR contain the ESPs of the input and aberrated constellations, respectively, with the aberration operator \({\hat{R}}_{\chi }\) acting on the ℓm-dimensional subspace spanned by the ESPs. The explicit form for the operator \({\hat{R}}_{\chi }\) is an upper triangular matrix containing the Wirtinger derivatives of the aberration function R(χ) up to the order ℓm, as we detail in the Supplementary note 131.

We conclude from Eq. (8) that the aberration of a vortex constellation is fully captured by a linear transformation of its ESPs. Furthermore, an intuitive physical/geometrical interpretation of the ESP transformations is possible by means of Newton’s identities33, which relate the ESPs to power sums of a set of complex roots. For example, e1 is proportional to the constellation barycenter, whose transformation contains the GH and IF beam shifts of vortex beams2,3,18,20. On the other hand, e2 and e3 give the second and third moments of the constellation positions with respect to the barycenter, which are related to the variance and the skewness of the constellation, respectively. For higher orders, the ESPs are sums of products of moments of the constellation positions that add up to that order, whose meaning we could not identify.

For clarity, let us explicitly consider the case of ℓm = 2. We choose the origin of the reference frame at the barycenter of the input constellation, such that the input field is ψI(ξ) ∝ ξ2 + eI2ξ0. From Eqs. (6) and (7), we obtain that

where \({R}_{\chi }^{{\prime} }{| }_{0}\) and \({R}_{\chi }^{{\prime\prime} }{| }_{0}\) are the first and second Wirtinger derivatives of R(χ) at χ = χ* = 0. Equation (9) shows the shift of the barycenter of the constellation by the known Artmann translator of a unit vortex12,18, which is the first order topological aberration of the constellation. In fact, this result, previously predicted only for perfect input vortices20, holds regardless of the particular geometry or the order of a vortex constellation. Furthermore, equation (10) shows the second-order topological aberration, which amounts to the stretching of the input constellation and its rotation around the barycenter.

Experiment

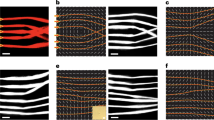

To observe the aberrations of the vortex constellations, we use the experimental setup depicted in Fig. 2. We use a fibre-coupled diode laser centred at the wavelength λ = 810 nm, operated below the lasing threshold and filtered by a narrow bandpass filter (Semrock, 3nm bandwidth). The beam is then polarised on a polarising beam-splitter (PBS) and divided with a non-polarising 50:50 beam-splitter (BS) into a probe beam, which we prepare with the desired constellation, and a reference beam, used afterwards for the generation of off-axis holograms. Furthermore, the polarisations of the probe and reference fields are set to be identical, and they are controlled by a half-wave plate placed after the BS.

BP, bandpass filter; ND, neutral density filter; M1, retro-reflecting mirror; PBS, polarising beam-splitter; BS, 50:50 non-polarising beam-splitter; HWP1 and HWP2, true-zero order half-wave plates; SLM, spatial light modulator; CMOS, camera sensor. The inset shows a breakdown of our reflecting object, which consists of an Au film assembled on a FS substrate and optically contacted to a FS prism.

To prepare the spatial profile of the probe beam, we shape it on a spatial light modulator (SLM, Holoeye Pluto 2.0) displaying a \(\exp (i{\ell }_{m}\phi )\) phase structure, without amplitude modulation, which naturally leads to a constellation tightly confined to the beam centre. We further tune the constellation by introducing wavefront aberrations by means of Zernike polynomials34, ensuring that all the ℓm vortices are clearly observable in our apparatus. As an additional precaution, we use a second PBS to prevent any undesired changes in polarisation due to the SLM.

Our aberrating device consists of a 35nm thick Au film assembled on the hypothenuse of a fused silica (FS) right-angle prism, in the so-called Kretschmann-Raether (KR) configuration35,36. The Au film is deposited on an FS substrate using electron beam-assisted evaporation and optically contacted to the prism with index-matching gel (Thorlabs G608N3). In the KR configuration, a P-polarised input beam can resonantly excite surface plasmons at the interface between FS and the Au film via attenuated total reflection (ATR), enhancing the angular gradients of the reflection coefficient, and hence the topological aberration imprinted on the reflected beam37. By measuring the power of the reflected S- and P-polarised probe beams as a function of the angle of incidence and using a transfer matrix model (See Supplementary Note 3 in ref. 31) to numerically fit the results, we determine the resonant ATR angle and the effective permittivity of the Au film to be θATR ≈ 45.02∘ and ϵf = −22.8456 + 1.2619i, respectively. Furthermore, since only P-polarised light excites surface waves, we use the reflected S-polarised field as a good approximation of the input field, allowing both the input and the aberrated constellations to be measured upon reflection. Finally, for our simulations we consider the aberration function R(χ) to be the fitted reflection coefficient for P-polarised light.

To measure the constellation coordinates, we superpose the probe and reference beams off-axis and record the interference patterns with a CMOS camera (IDS U3-3650XLE-M-GL, 2.2 μm pixel size), from which both the intensity and phase profiles are digitally retrieved38,39. To measure the constellations at different angles of incidence, we rotate the prism using a motorised rotation stage (Thorlabs PRM1/MZ8) while maintaining the camera fixed. The acquired constellations are then shifted in post-processing, so as to centre the origin of the reference frame at the barycenter of the input constellation.

It is worth noting that the measured constellations are affected significantly by interference with stray light coming from the protective glass window on the CMOS sensor, the reflective layers of the beam-splitters, etc., which cannot be eliminated in post-processing due to the propagation direction being almost identical to the probe field. Such interferences deform the input constellation even more than the topological aberration effect, and prevent the accurate observation of the phenomenon. To eliminate these unwanted interference effects, we operated the laser diode below the lasing threshold, shortening the coherence length of the light source to sub-millimetre scale at the cost of requiring precise control of the path length difference between reference and probe beams. Alternatively, a pulsed laser with sufficiently short pulse duration could also be used, provided that the effect of a finite bandwidth is taken into account in the modelling of the aberration function. Finally, we determine the constellation coordinates from the retrieved phase profiles using the algorithm detailed in the Supplementary note 431.

We show in Fig. 3 our experimental results for constellations with 1 ≤ ℓm ≤ 3. In Fig. 3a we show the logarithmic Wirtinger derivative of the reflection coefficient, retrieved from the shifts in the barycenters of the constellations using Eqs. (6) and (9). We see that the retrieved derivatives accurately follow the theoretical curves simulated from the measured material parameters under the assumption \({R}_{\chi }^{(n)}{| }_{0}\approx {R}_{{k}_{x}}^{(n)}{| }_{0}/{2}^{n/2}\). Such an approximation is reasonable in our case, since kxkz is the plane of incidence, and the constellations are prepared and measured in the same polarisation. We note that, unlike the shifts in the center of mass for the vortex-carrying fields12,20, the measured barycenter shifts do not depend on the total topological charge ℓm. This result is a direct measurement of the first-order topological aberration of a vortex constellation, which, despite its strong correspondence to the GH and IF shifts, had not yet been observed. Furthermore, the barycenter shifts we report are greatly enhanced compared to those of dielectric interfaces, reaching more than 30 wavelengths in magnitude. A similar enhancement of the GH shift has been reported in37 for Gaussian beams, which here we extend to vortex beams and out-of-plane (IF) shifts.

a First, b second and c third Wirtinger derivatives of the reflection coefficient for P-polarised light, retrieved from the measured vortex constellations for 1 ≤ ℓm ≤3. In each plot, the real (imaginary) part is shown as filled (hollow) markers for measured data, and as solid (dashed) curves for theoretical simulations. Additionally, in d and e we show the measured vortex constellations of the input field (crosses) and the reflected field (circles) with ℓm = 2 in d. and ℓm = 3 in e. All error bars are standard deviations calculated from the precision of the singularity positioning, detailed in Supplementary note 531. The measured constellations are shown for the 15 angles of incidence highlighted on the x axis of b and c.

Lastly, in Fig. 3c we show the third Wirtinger derivative of the reflection coefficient, retrieved from the changes in the third-order ESPs of the ℓm = 3 constellation. In this case, the experimental results diverge more substantially from the theoretical simulations. By investigating the reflection process with simulated input constellations, we found this discrepancy to be associated to the noticeable radial features in the intensity profile of the field, caused by the lack of amplitude modulation in the mode preparation. A detailed comparison between the measured and simulated fields is provided in the Supplementary note 531. Furthermore, the intensity and phase profiles fields from which the data of Fig. 3 was taken can be found the Supplementary video file40.

Measuring the coordinates of a singularity constellation becomes increasingly challenging as the constellation order increases, since the intensity near the singularity positions decreases exponentially with ℓm. In our case, properly exposing the holograms near the singularity positions for ℓm > 3 requires exposure times that are long enough for the phase between the probe and reference fields to drift due to mechanical instabilities, leading to a decreased accuracy in the determination of the singularity positions. Nonetheless, we show in Fig. 3e the raw constellation coordinates for the set of angles highlighted by an arrow in Fig. 3c. Here, the deformation of the P-polarised constellations as well as the shift of the barycenter can be clearly seen.

In this article, we developed a new framework to describe the topological aberration of vortex constellations and reported on the first observation of the phenomenon predicted more than a decade ago20. We showed that aberrations generally affect the elementary symmetric polynomials of a constellation’s coordinates, from which the angular Wirtinger derivatives of the aberration can be directly retrieved. We demonstrate the effect experimentally by measuring the topological aberrations of vortex constellations with up to 3 vortices upon attenuated total reflection, where aberration effects are enhanced by the resonant excitation of surface plasmon polaritons on the interface between a thin metallic film and a dielectric medium. An exciting perspective for our work is the extension to more complex singular light fields featuring, for example, polarisation singularities17, spatiotemporal vortices41,42, vortex knots29,30 and polarisation knots43. Beyond light waves, we expect our work to inspire connections to other fields of physics where complex vortex constellations and symmetric polynomials appear, such Bose-Einstein condensates, superfluids24,25,26,27, and even topological field theories28.

Methods

Data availability

The full resolution images containing the off-axis holograms from where the data of Fig. 3 was retrieved are provided in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26235362.

Code availability

The Matlab codes used for the processing of the off-axis holograms used in the experiment, including the code used for measuring the positions of the vortex constellations, are provided in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26235665.

References

Jackson, J. D. & Fox, R. F. Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd ed. Am. J. Phys. 67, 841 (1999).

Bliokh, K. Y. & Aiello, A. Goos–hänchen and imbert–fedorov beam shifts: an overview. J. Opt. 15, 014001 (2013).

Aiello, A. Goos–hänchen and imbert–fedorov shifts: a novel perspective. N. J. Phys. 14, 013058 (2012).

Goos, F. & Hänchen, H. Ein neuer und fundamentaler versuch zur totalreflexion. Ann. der Phys. 436, 333 (1947).

Merano, M., Aiello, A., Van Exter, M. & Woerdman, J. Observing angular deviations in the specular reflection of a light beam. Nat. Photonics 3, 337 (2009).

Jayaswal, G., Mistura, G. & Merano, M. Observation of the imbert–fedorov effect via weak value amplification. Opt. Lett. 39, 2266 (2014).

Bliokh, K. Y., Rodríguez-Fortuño, F. J., Nori, F. & Zayats, A. V. Spin–orbit interactions of light. Nat. Photonics 9, 796 (2015).

Okuda, H. & Sasada, H. Huge transverse deformation in nonspecular reflection of a light beam possessing orbital angular momentum near critical incidence. Opt. Express 14, 8393 (2006).

Okuda, H. & Sasada, H. Significant deformations and propagation variations of laguerre-gaussian beams reflected and transmitted at a dielectric interface. JOSA A 25, 881 (2008).

Fedoseyev, V. Spin-independent transverse shift of the centre of gravity of a reflected and of a refracted light beam. Opt. Commun. 193, 9 (2001).

Fedoseyev, V. Transformation of the orbital angular momentum at the reflection and transmission of a light beam on a plane interface. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 41, 505202 (2008).

Bliokh, K. Y., Shadrivov, I. V. & Kivshar, Y. S. Goos–hänchen and imbert–fedorov shifts of polarized vortex beams. Opt. Lett. 34, 389 (2009).

Dasgupta, R. & Gupta, P. Experimental observation of spin-independent transverse shift of the centre of gravity of a reflected laguerre–gaussian light beam. Opt. Commun. 257, 91 (2006).

Allen, L., Beijersbergen, M. W., Spreeuw, R. J. C. & Woerdman, J. P. Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of laguerre-gaussian laser modes. Phys. Rev. A 45, 8185 (1992).

Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H. et al. Roadmap on structured light. J. Opt. 19, 013001 (2016).

Nye, J. F. & Berry, M. V. Dislocations in wave trains. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 336, 165 (1974).

Berry, M. V., Dennis, M. R. & Lee, R. L. Polarization singularities in the clear sky. N. J. Phys. 6, 162 (2004).

Merano, M., Hermosa, N., Woerdman, J. P. & Aiello, A. How orbital angular momentum affects beam shifts in optical reflection. Phys. Rev. A 82, 023817 (2010).

Löffler, W., Aiello, A. & Woerdman, J. P. Observation of orbital angular momentum sidebands due to optical reflection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 113602 (2012).

Dennis, M. R. & Götte, J. B. Topological aberration of optical vortex beams: determining dielectric interfaces by optical singularity shifts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 183903 (2012).

Freund, I. Critical point explosions in two-dimensional wave fields. Opt. Commun. 159, 99 (1999).

Ricci, F., Löffler, W. & Van Exter, M. Instability of higher-order optical vortices analyzed with a multi-pinhole interferometer. Opt. express 20, 22961 (2012).

Neo, R. et al. Correcting vortex splitting in higher order vortex beams. Opt. Express 22, 9920 (2014).

Butts, D. A. & Rokhsar, D. S. Predicted signatures of rotating Bose–Einstein condensates. Nature 397, 327 (1999).

Fetter, A. L. Rotating trapped bose-einstein condensates. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 647 (2009).

Salomaa, M. M. & Volovik, G. E. Quantized vortices in superfluid 3He. Rev. Mod. Phys. 59, 533 (1987).

Aharon-Steinberg, A. et al. Direct observation of vortices in an electron fluid. Nature 607, 74 (2022).

Witten, E. Topological quantum field theory. Commun. Math. Phys. 117, 353 (1988).

Leach, J., Dennis, M. R., Courtial, J. & Padgett, M. J. Knotted threads of darkness. Nature 432, 165 (2004).

Dennis, M. R., King, R. P., Jack, B., O’Holleran, K. & Padgett, M. J. Isolated optical vortex knots. Nat. Phys. 6, 118 (2010).

See the Supplementary Material text at [URL to be defined] (2024)

Osgood, W. F.Topics in the theory of functions of several complex variables, Vol. 2 (Dover publications, 1966)

Cohn, P.https://books.google.fi/books?id=AbZvQgAACAAJClassic Algebra (Wiley, 2000)

Lakshminarayanan, V. & Fleck, A. Zernike polynomials: a guide. J. Mod. Opt. 58, 545 (2011).

Kretschmann, E. & Raether, H. Notizen: Radiative decay of non radiative surface plasmons excited by light. Z. f.ür. Naturforsch. A 23, 2135 (1968).

Akimov, Y., Pam, M. E. & Sun, S. Kretschmann-raether configuration: revision of the theory of resonant interaction. Phys. Rev. B 96, 155433 (2017).

Yin, X., Hesselink, L., Liu, Z., Fang, N. & Zhang, X. Large positive and negative lateral optical beam displacements due to surface plasmon resonance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 372 (2004).

Goodman, J. W. & Lawrence, R. Digital image formation from electronically detected holograms. Appl. Phys. Lett. 11, 77 (1967).

Verrier, N. & Atlan, M. Off-axis digital hologram reconstruction: some practical considerations. Appl. Opt. 50, H136 (2011).

See the Supplementary File at [URL to be defined], where the intentisy and phase profiles of the fields measured in the experiment are shown. (2024)

Jhajj, N. et al. Spatiotemporal optical vortices. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031037 (2016).

Chong, A., Wan, C., Chen, J. & Zhan, Q. Generation of spatiotemporal optical vortices with controllable transverse orbital angular momentum. Nat. Photonics 14, 350 (2020).

Larocque, H. et al. Reconstructing the topology of optical polarization knots. Nat. Phys. 14, 1079 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jörg Gotte and Mark Dennis for inspiring discussions at the ICOAM 2022. We also thank Vyacheslavs Kashcheyevs for the valuable discussions on BECs, and Matias Eriksson for the helpful comments on the data processing. R. B. acknowledges the support of the Academy of Finland through the postdoctoral researcher funding (decision 349120). M. H. acknowledges support from the Doctoral School of Tampere University, Emil Aaltonen foundation, and the Magnus Ehrnrooth foundation through its graduate student scholarship R. F. acknowledges the support of the Academy of Finland through the Academy Research Fellowship (decision 332399). All authors acknowledge the support of the Academy of Finland through the Competitive Funding to Strengthen University Research Profiles (decision 301820) and the support of the Photonics Research and Innovation Flagship (PREIN - decision 320165).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The theoretical study was conducted by R.B and M.O. The experimental setup and measurements were performed by R.B. The fabrication of the thin Au film was conducted by S.B. The data analysis was performed by R.B. and M.H. The numerical simulations were performed by R.B. and S.B. The data analysis and on the singularity-tracking algorithm were performed by R.B. and M.H. The manuscript was written by R.B., and edited by all authors. R.F. and M.O. supervised and assisted at every stage of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alessio D’Errico and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barros, R.F., Bej, S., Hiekkamäki, M. et al. Observation of the topological aberrations of twisted light. Nat Commun 15, 8162 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52529-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52529-6