Abstract

The eastern tropical Pacific has defied the global warming trend. There has been a debate about whether this observed trend is forced or natural (i.e., the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation; IPO) and this study shows that there are two patterns, one that oscillates along with the IPO, and one that is emerging since the mid-1950s, herein called the Pacific Climate Change (PCC) pattern. Here we show these have distinctive and distinguishable atmosphere-ocean signatures. While the IPO features a meridionally broad wedge-shaped SST pattern, the PCC pattern is marked by a narrow equatorial cooling band. These different SST patterns are related to distinct wind-driven ocean dynamical processes. We further show that the recent trends during the satellite era are a combination of IPO and PCC. Our findings set a path to distinguish climate change signals from internal variability through the underlying dynamics of each.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

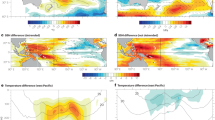

The sea surface temperature (SST) trends over 1980 to 2022, and the longer period of 1958 to 2022, are shown in Fig. 1a, b. We will show that the former is largely the well-known pattern of the long-studied Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO; see Methods for a definition) and the latter is a pattern that we will call the Pacific Climate Change (PCC) pattern. We further show that the ocean dynamics associated with the two patterns are distinct.

The SST trend (°C per decade) based on HadISST during (a) 1980–2022 and (b) 1958–2022. Dots in (a, b) indicate the trend exceeding the 95% confidence level. c Timeseries of raw (black dashed lines) and 15-year running mean (red solid lines) annual-mean SST anomalies in the cold tongue (top panel; 5°S–5°N, 190°W–270°W) and the warm pool (bottom panel; 5°S–5°N, 140°E–170°W). The SST anomalies were calculated relative to the climatology of the first 50 years (1870–1919). d Pattern correlations of 43-year SST trends in the tropical Pacific region (30°S–30°N, 120°E–270°W) in historical period with the trend during 1980–2022 based on HadISST (black solid line), ERSSTv5 (green dashed line), Kaplan (red dotted line) and COBE (blue dashed line). Shading in (d) indicates pattern correlations of 43-year SST trends in the tropical Pacific region with the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) pattern based on HadISST. e Similar to (d) but for 65-year SST trends with the trend during 1958–2022. Arrows labeled P1 (1870–1912), P2 (1914–1956) and P3 (1942–1984) indicate the periods with strongest positive and negative correlations in (d) and P4 (1870–1934) with strongest negative correlation in (e).

The fact that under greenhouse gas (GHG) -driven global warming some parts of Earth do not warm, or even cool, presents a fascinating problem. The surface tropical eastern Pacific stands out as a region that resists warming1. Whether evaluated over recent decades or back to 1900, the tropical Pacific exhibited what is often called a “La Niña-like” trend pattern with pronounced warming in the west and lack of warming in the cold tongue region1,2,3,4,5,6. This SST pattern is associated with cooling and shoaling of the tropical Pacific Ocean thermocline over past decades5,6. In contrast, state-of-the-art climate models most often respond to anthropogenic GHG forcing by warming the eastern Pacific, a pattern that is often referred to as “El Niño-like”7,8. Numerous studies have sought to reconcile this discrepancy and two primary arguments have been proposed. One suggests that correcting the cold tongue bias in the models’ mean state would align the models’ trends with observations, which are argued to be a forced response5. The other suggests that the recent observed trend is largely due to internal variability and is within the range of climate model simulations9,10.

Although debate persists11,12,13, the Coupled Model Intercomparison Projects (CMIP) models and Large Ensembles rarely come close to the observed trends either as a response to radiative forcing, internal variability or any combination thereof. Alternatively, we may use observations to estimate the forced climate response. However, observational analyses come with their own limitations. Beyond inescapable observational error/uncertainty14,15, the tropical Pacific is dynamically active on decadal to multi-decadal timescales, so that internally generated long-term variability may overwhelm the climate change signal16,17. For example, the transition from positive to negative phases of the IPO— the dominant climate mode in the Pacific ocean on decadal to multi-decadal time scales and closely related to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation18,19,20,21 —contributed to the observed La Niña-like SST trend pattern over the past four decades16,22,23. It has been argued that some individual ensemble members appear able to reproduce the observed trend pattern over the recent four decades because their randomly generated internal variability aligns, by chance, with the observed IPO phase transition24. However, long-term change in the tropical Pacific exhibits distinctive patterns unlike those on these decadal timescales. While SST anomalies associated with the IPO in the tropical Pacific typically feature a meridionally broad pattern21, the long-term lack of warming is found to be narrowly confined to the cold tongue2,4,5,6,14. Seager et al.6 further elaborate that some individual model simulations, containing both internal variability and the model’s forced response, come close to the observations but nonetheless fail to represent several fundamental elements of the observed long-term trends, including the distinctive narrowness of the lack of warming and the underlying subsurface ocean dynamical processes. These findings suggest that the tropical Pacific’s responses to anthropogenic forcing might present unique characteristics that set them apart from those typically associated with internal decadal variability.

Results

Recurrent IPO pattern and emerging pattern related to Pacific Climate Change (PCC)

The SST trend pattern after the satellite data become available (1980–2022) is often used as the observational reference for assessing climate model simulations of the forced response (Fig. 1a). This SST trend pattern is characterized by meridionally broad negative anomalies in the tropical Pacific, particularly south of the equator, and positive anomalies in the northwestern and southwestern Pacific. It is akin to that of the typical IPO variability on decadal to multi-decadal scale18,20,22,23 (Fig. S1a). If this trend is the positive to negative phase transition of the IPO, then it should appear in earlier historical periods, given that the IPO has experienced several phase transitions from 1870 to 2022 (Fig. S1b). In Fig. 1d we show pattern correlations of this short-term trend during 1980–2022 with tropical Pacific SST trends across all time spans of 43 years in the observational record (e.g., 1979 to 2021, 1978 to 2020, … 1870 to 1912) over 30°S–30°N, 120°E–270°W. The pattern correlations range from around −0.8 to 1, demonstrating an oscillatory behavior matching the IPO’s phase transitions over the last century (Fig. S1b). Analyses for the whole Pacific (60°S–60°N, 120°E–270°W) or the equatorial Pacific (10°S–10°N, 120°E–270°W) yield similar conclusion.

A different SST trend pattern beginning in the mid-1950s is shown in Fig. 1b. The start year 1958 is chosen to approximate the time when the tropical Pacific warm pool starts to warm up5,6 (Fig. 1c, lower panel), and because it is the start year of the Ocean ReAnalysis System-5 (ORAs5)25. The lack of warming in the tropical Pacific is still evident in this longer trend pattern (Fig. 1b). However, it is markedly confined meridionally to the equatorial region, unlike the much broader meridional distribution in Fig. 1a that is indicative of the IPO. Also, the warm anomalies in the northwestern and southwestern Pacific are less pronounced. This long-term trend pattern during 1958–2022 shows an emerging feature as evidenced in its pattern correlation with historical trends for equivalent earlier 65-year spans. As the end year of the trend is adjusted backward, the pattern correlation shows a rapid decline and lingers around zero in earlier periods (Fig. 1e). It suggests that this long-term trend pattern has no close historical analogues or anti-analogues, and we herein referred to the trend pattern during 1958–2022, which emerges from the background “noise” of internal variability, as the PCC pattern.

In Fig. 1d we identify periods with the strongest negative (P1:1870–1912 and P3:1942–1984) and strongest positive (P2: 1914–1956) pattern correlations with the short-term trend during 1980–2022. However, the recent southward-displaced center of the cooling in the eastern Pacific (Fig. 1a) is less apparent in these historical periods, suggesting that it might be due to climate change rather than internal variability26,27. Additionally, we show pattern correlations of the IPO pattern (Fig. S1a) with all 43-year SST trends in the tropical Pacific (shadings in Fig. 1d), which are strongly consistent with those related to the short-term trend during 1980–2022, though less so in the most recent periods. It suggests that while the IPO generally dominates the short-term trend patterns, the PCC leaves discernable imprints on the short-term trends in recent decades.

In Fig. 1e we identify the strongest negative pattern correlation (P4: 1870–1934) with the PCC pattern (Fig. S1c–f). The trend pattern in P4 (Fig. S1f) appears to be a weak reflection of the IPO pattern rather than a negative analogue of the PCC pattern, again confirming the distinctiveness of the PCC SST trend pattern that has emerged recently. The recurring feature of the short-term trend and the emerging feature of the long-term trend identified in HadISST data were consistently found across different SST datasets (ERSSTv5, Kaplan, COBE; Fig. 1d, e and S2). Further, Fig. 2a, b shows the histogram of historical period pattern correlations with short-term trend pattern during 1980–2022 and the PCC pattern, respectively. The overall distribution for the pattern correlations with the short-term trend is an approximately symmetrical distribution around zero over time. Trend patterns of both the same and opposite signs appear in earlier and later decades. In contrast, pattern correlations with the PCC pattern increasingly skew towards positive values in recent decades and there are no past anti-analogues of the PCC pattern.

a Histograms of pattern correlations of 43-year SST trend patterns over the tropical Pacific (30°S–30°N, 120°E–270°W) in historical period with that during 1980–2022. b Similar to (a) but for the 65-year SST trend. c Quantification of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO)’s contribution to the trend of zonal SST gradient in the equatorial Pacific (see Methods). The red solid line indicates the 43-year trend, and the red dashed line indicates the IPO’s contribution. Similarly, the blue solid line and dashed line indicate the 65-year trend and the IPO’s contribution, respectively. d The 43-year SST trend (°C per decade) in 1970–2012 with near-zero IPO contribution. Dots in (d) indicate the trend exceeding the 95% confidence level.

Next we quantified the IPO’s contribution to the short- and long-term SST trends (Fig. 2c) by comparing the total trend in the tropical Pacific zonal SST gradient with the IPO’s contribution. The latter is calculated as the product of the trend in the IPO index over different time spans and the IPO-related zonal SST gradient as shown in Fig. S1 (see Methods). Consistent with Fig. 2a, b, the IPO variability predominantly shapes both the short-term and long-term trends during the earlier period when the climate change signal is relatively weak. In the recent period, however, the imprints of climate change are distinctly reflected in both short-term and long-term trends (Fig. 2c). As shown in Fig. 2c, the IPO accounts for over half of the observed zonal SST gradient trend during 1980–2022 (Fig. 2c), suggesting that the trend over the past four decades is a combination of IPO and PCC. In contrast, the impact of the IPO on the most recent long-term trend during 1958–2022 is minor. Moreover, short-term trends with a negligible IPO impact, such as that from 1970 to 2012 (Fig. 2d), closely resembles the emerging PCC SST pattern (Fig. 1b).

Distinct ocean dynamics for the IPO and the PCC

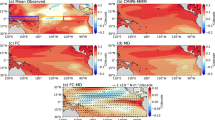

A closed Bjerknes feedback loop requires changes in the surface wind stress and the subsurface thermocline depth, to accompany the SST variations28,29. In Fig. 3, we show a recent short-term dipole-like pattern of thermocline depth (Fig. 3a) that recurs historically (Fig. 3e). In contrast, the emerging PCC SST trend pattern is accompanied by an overall shoaling throughout the tropical Pacific (Fig. 3b–e). Also, the recurring surface wind stress pattern in the equatorial Pacific features a broad strengthening of the zonal wind stress across the basin (Fig. 3c–e), while the PCC wind stress trend pattern in the equatorial Pacific displays a dipole structure with strengthened wind stress in the central Pacific and weakened wind stress in the eastern Pacific (Fig. 3d–f). We also examined the variability of the surface wind stress and the subsurface thermocline depth that are directly linked to the IPO (Fig. S3). These IPO-related patterns with dipole-like thermocline variability and same-signed wind stress variability in the tropical Pacific bear a close resemblance to the short-term trends (Fig. 3a–c). This supports the argument that the short-term trends over the span of approximately an IPO cycle predominantly reflect the internal variability of the IPO, manifest across the tropical Pacific upper ocean and atmosphere.

The thermocline depth trend (m/decade) based on ORAs5 subsurface temperature during (a) 1980–2022 and (b) 1958–2022. The surface wind stress (vectors; N/m2) and SSH (contours; m/decade) trend during (c) 1980–2022 and (d) 1958–2022. Dots in (a, b) and (c, d) indicate the trend in thermocline depth and SSH exceeding the 95% confidence level, respectively. e Pattern correlations of 43-year trend patterns in historical period for the thermocline depth (red lines), SSH (blue lines) and zonal wind stress (green lines) in the tropical Pacific region (30°S–30°N, 120°E–270°W) based on SODA (solid lines) and ORAs5 (dashed lines) with the corresponding trend during 1980–2022 based on ORAs5. f Similar to (e) but for 65-year trend with the trend during 1958–2022 based on SODA.

In the tropical Pacific, the thermocline depth and SSH are closely linked to each other and exhibit similar interannual fluctuations associated with El Niño-Southern Oscillation29,30. On decadal timescales, the dipole-like pattern is characterized by much higher SSH in the tropical western Pacific compared to the east (Fig. S3b), and thermocline deepening in the west and shoaling in the east (Fig. S3a). These are also present in the short-term trends during 1980–2022 (Fig. 3a–c). Unlike the short-term trend of SSH, the PCC trend exhibits an overall, but small, sea level fall in the central-to-eastern equatorial Pacific region, which is accompanied by sea level rise in the off-equatorial regions (Fig. 3d). The PCC thermocline depth trend is also different from the short-term trend in that it has shoaling or little change across the basin, though the shoaling is greater in the east (Fig. 3b). The short-term trends of thermocline depth-SSH-wind stress associated with the IPO oscillate back and forth together (Fig. 3e) but those associated with the PCC trend are collectively emerging over time (Fig. 3f).

These observed SSH and thermocline trends were previously demonstrated to be some combination of wind-driving, thermal expansion and the influence of changes in the Earth’s gravity field due to loss of land ice31,32,33. While there is general consensus on zonal dipole-like SSH change being related to internal variability in both observations34 and CMIP models35, the anthropogenic contribution to SSH change remains elusive33,35,36. Our subsequent analyses use a simple 1.5-layer reduced-gravity model to investigate the wind-driven component of SSH, thermocline depth, and circulation (see details in Methods; note that the same dynamics can be formulated as describing a single baroclinic vertical mode and hence have more general applicability37,38). We simplify further by solving an equilibrium version of the reduced gravity system analytically (see Methods, Eq. (6)). As shown in Fig. 4a, b, both the IPO-related short-term trend and the PCC-related long-term trend can be simulated quite realistically with this simple model by prescribing their corresponding surface wind stress trend patterns. The pattern correlations between observations and model for the observed and wind stress-driven SSH trend patterns are 0.87 for the short-term trend during 1980–2022 and 0.72 for the PCC trend in the tropical Pacific: 76% and 52% of the variance, respectively. This demonstrates the dominant role of the wind-driven redistribution of the heat content in the tropical Pacific upper ocean for both IPO-related variability and the emerging PCC signal. According to Eq. (6), variations in SSH are determined by the surface wind stress and its horizontal gradients zonally integrated from the eastern boundary. The spatial distribution of the wind stress effects (B in Eq. (6); Fig. 4c, d) underscores that it is the wind stress and its horizonal gradients in the central tropical Pacific that are most important in redistributing the heat content and driving the SSH changes in the tropical Pacific, for both climate change and decadal variability.

The wind stress-driven SSH trend (m per decade) during (a) 1980–2022 and (b) 1958–2022 based on Eq. (6). The pattern correlations between the wind stress-driven and observed SSH trend pattern over the region of 20°S–20°N, 120°E–270°W are also displayed. The wind stress effect (m per decade) at each grid point (defined as \(B=\frac{f}{{{\rho }_{0}g}^{{\prime} }\bar{h}}{curl}(\frac{\tau }{f}),\) in Eq. (6)) during (c) 1980–2022 and (d) 1958–2022. The integrated wind stress effect from the eastern boundary in combination with the damping effect yields the wind stress-driven SSH change pattern.

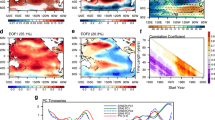

The different wind stress patterns also drive different ocean circulation changes. Figure 5a–c presents the zonally averaged ocean current trends over 3°S–3°N, 150°E–90°W associated with the recurrent short-term (red lines) and emerging PCC-related long-term (blue lines) trends. We also display the IPO-related ocean current trends during 1980–2022 (gray lines in Fig. 5a–c), which exhibit a strong consistency with the short-term trends. The most striking difference between the PCC trends (blue line in Fig. 5a) and trends contributed by the IPO phase transition (gray line in Fig. 5a) is the opposite-signed surface zonal currents in the equatorial and north off-equatorial regions. There is a significant strengthening of the surface westward zonal currents in the central equatorial Pacific for the decadal IPO variability (gray line in Fig. 5a and shadings in Fig. 5d). In contrast, the emerging pattern shows a weakening of westward surface currents in the central-to-eastern Pacific (blue line in Fig. 5a and shadings in Fig. 5e). The changes in surface zonal currents in the tropical Pacific are predominantly governed by its geostrophic component (Eqs. (7–8); contours in Fig. 5d, e), determined by the wind-driven SSH (Fig. 4). Wind stress also impacts Ekman pumping (Eq. (11)). While the decadal IPO upwelling pattern is approximately symmetric around the equator (gray line in Fig. 5c), the meridional center of the emerging upwelling pattern is displaced to near 5°S (blue line in Fig. 5c). The overall strengthening of zonal wind stress across the equatorial Pacific linked to decadal variability fosters pronounced upwelling from the western to eastern equatorial Pacific (Fig. 5f). In comparison, the emerging PCC wind stress pattern contributes to enhanced upwelling in the central equatorial Pacific and weakened upwelling to the east, while stronger trade winds south of the equator contribute to increased local upwelling (Fig. 5g), thereby accounting for the different meridional locations of upwelling change (Fig. 5c). The meridional currents averaged in the mixed layer, indicative of the strength of the shallow overturning circulation, are quite similar for the short-term and long-term trends, showing a consistent strengthening of the poleward transport in both hemispheres, though of different magnitudes (Fig. 5b).

Zonal mean (3°S–3°N) trend of (a) surface zonal current (m/s per decade), (b) upper 50-m averaged meridional current (m/s per decade) and (c) vertical current at the 50-m depth (m/day per decade) over the tropical central-to-eastern Pacific (150°E–90°W) during 1980–2022 (blue lines) and 1958–2022 (red lines). The Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO)-related trend during 1980–2022 in surface zonal current (m/s per decade), upper 50-m averaged meridional current (m/s per decade) and vertical current at the 50-m depth (m/day per decade) are also shown in gray lines for comparison (see details for IPO-related trends in Methods). d The IPO-related trend during 1980–2022 in surface zonal current (shadings; m/s per decade) and its geostrophic component (\({u}_{g}\) outside the equatorial region and \({u}_{{sg}}\) at the equator; contours; m/s per decade, at 0.01 m/s intervals with the zero line omitted) calculated based on Eqs. (7–8) using ORAs5 data. e The surface zonal current trend (shadings; m/s per decade) and its geostrophic component during 1958–2022 (contours; m/s per decade, at 0.01 m/s per decade intervals with the zero line omitted). Dots in (d, e) indicate the observed trend exceeding the 95% confidence level. f, g Similar to (d, e) but for the Ekman pumping (\({w}_{E}\)) calculated based on Eqs. (9–11). Dots in (f, g) indicate the values exceeding the 95% confidence level.

The IPO and PCC-related temperature changes (Eqs. (12–13)) in the equatorial Pacific occur via different wind-driven ocean dynamical processes (Fig. 6). The IPO-related short-term cooling in the equatorial eastern Pacific (Fig. 1a) is primarily driven by a strengthened zonal current (Fig. 5d) and advective cooling (\({UaTc}\)) (Fig. 6a). Enhanced poleward transport (\({VaTc}\)) and thermocline shoaling (\({WcTa}\)) also contribute to the IPO-related cooling in the equatorial region. The PCC cooling is relatively weaker because warming due to a weaker zonal current in the east largely offsets the cooling effect related to the thermocline feedback due to the thermocline shoaling (Fig. 6b). The meridional temperature gradient strengthens more for the narrow PCC than the broad IPO (Fig. 1b), such that only for the PCC does meridional temperature gradient (\({VcTa}\)) contribute cooling in the central-to-eastern Pacific (Fig. 6a, b). Although the vertical upwelling changes are evident for the equatorial region, the Ekman pumping term’s (\({WaTc}\)) contributions to the wider equatorial Pacific (5°S–5°N) temperature change are minor for both the IPO and the PCC, which might be due to the immediate opposite-signed effect off the equator for both.

Heat budget terms for the mixed layer temperature averaged over the eastern equatorial Pacific (5°S–5°N, 190°W–270°W; left box in Fig. 1b) including ocean current change (\({UaTc}\), \({VaTc}\), \({WaTc}\)), temperature gradient change (\({UcTa}\), \({VcTa}\), \({WcTa}\)), nonlinear terms (\({UaTa}\), \({VaTa}\), \({WaTa}\)) and their sum (SUM) related to (a) the IPO-related and (b) the emerging PCC-related sea surface temperature (SST) trend (°C/month per decade; see Mixed layer heat budget analysis for the long-term SST Change in Methods for detailed explanation). Dotted bars indicate heat budget terms exceeding 90% significance tests.

Discussion

Much recent work focused on whether equatorial Pacific cooling over past decades is driven by anthropogenic effects or arises from internally-generated climate variability, like the IPO. A definitive anthropogenic link to the recent trends would allow us to reliably predict a cooler tropical Pacific. As the tropical Pacific is known to be a climatic pacemaker, for (at least) the near-future this would mitigate global warming via ocean heat uptake and low-level cloud feedbacks. Instead, if the cyclic IPO dominates the recent cooling, we may expect a strong warming when it reverses. In support of the first possibility, we have identified an emerging climate change signal in the tropical Pacific across different observational datasets and we call it the PCC. The PCC has distinctive ocean-atmosphere dynamics that differ from those associated with the IPO. We further demonstrate that the recent trends during the satellite era, which have been the focus of significant attention, result from a combination of IPO and PCC. The emerging PCC SST trend pattern features a narrow band of cooling in the eastern equatorial Pacific and warming elsewhere. This SST change is linked to thermocline shoaling/SSH decreases in the central-to-eastern Pacific and dipole-like changes in zonal surface wind stress. In contrast, the recurrent IPO-driven SST trend pattern is characterized by a meridionally broader cooling in the eastern Pacific, zonal dipole-like thermocline/SSH changes and an overall strengthening of tropical Pacific zonal wind stress. We have shown that these distinct ocean circulation changes are a response to different wind stress patterns. These oceanic responses account for surface cooling in the eastern Pacific, with the thermocline shoaling playing a dominant role in the PCC cooling and enhanced zonal advective cooling mainly driving the IPO-related cooling.

While basic geophysical fluid dynamics proved sufficient to attribute the observed oceanic changes to surface wind stress, we have not addressed the origins of the wind stress patterns associated with the PCC and the IPO. New research is needed to elucidate the wind changes, but our leading hypothesis is as follows. In response to GHG forcings39,40 temperature change in the upper troposphere are stronger than at the surface (Fig. S4), increasing atmospheric static stability. Consequently, the initial SST and surface wind response to rising GHGs might not be amplified as efficiently via Bjerknes feedback as is that for the internal modes on interannual to decadal timescales. Given the differences in thermocline and ocean current patterns associated with the PCC and the IPO, the coupled feedbacks related to ocean dynamics are also expected to differ, potentially contributing to distinct climate pattern formations for decadal variability and climate change. Additionally, climate variations outside of the tropical Pacific may influence the tropical Pacific trade winds26,27,41,42,43,44. Further, it has been argued that pronounced decadal-to-multidecadal SST variability in the Atlantic Ocean is also dominated by the response to the same external forcing that the tropical Pacific encounters45. Perhaps the co-occurrence of these long-term trends in different regions is not simply a direct response to rising GHGs but is influenced by inter-basin interactions. More work is needed to disentangle causal relationships among the long-term changes in different basins46,47.

Throughout this paper we have taken for granted the widespread assumption that the IPO is an internal mode of the climate system. However, while we worked to distinguish between the recurrent IPO-related decadal variability and the emerging PCC signal, we are open to the possibility that these two may have become coupled together by anthropogenic forcing. They have much in common: shoaling of the thermocline in the east, enhanced upwelling somewhere in the central-to-eastern equatorial Pacific and an enhanced zonal SST gradient across the equatorial Pacific. It seems reasonable to postulate that if the response to radiative forcing is the emerging PCC pattern seen here, then it could initiate coupled ocean-atmosphere feedbacks that favor a negative IPO state that also has an enhanced SST gradient24. This might explain why the most recent IPO swing has been extreme and robust (Fig. S1b). If so, this suggests that in nature forcing is projecting onto natural modes of variability, while it is not clear whether climate models can reproduce this behavior. A new perspective on how internal variability interacts with the climate change signal will be needed in future studies.

Methods

Datasets

The SST data used here are the Hadley Centre data HadISST version 1.1 with horizontal resolutions of 1° × 1° 48, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ERSSTv5 data with horizontal resolutions of 2° × 2° 49, the Centennial in Situ Observation Based Estimates of SST (COBE) from the Japanese Meteorological Agency with horizontal resolutions of 1° × 1° 50, and Kaplan Extended SST version 2 with horizontal resolutions of 5° × 5° 51. HadISST, ERSSTv5, and Kaplan were used from 1870 to 2022 and COBE from 1890 to 2022. We utilized subsurface temperature, surface wind stress, SSH, zonal and meridional currents from ORAs5 during 1958–2022 with horizontal resolutions of 0.25° × 0.25° and 75 vertical levels, the latest ocean reanalysis products provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts25. The vertical velocity for ORAs5 was derived from zonal and meridional currents based on mass continuity52. We also used subsurface temperature and surface wind stress from the Simple Ocean Data Assimilation (SODA), version 2.2.4 with horizontal resolutions of 0.25° × 0.25° and 40 vertical layers during 1871–197953, in conjunction with the version 3.3.2 with horizontal resolutions of 0.25° × 0.25° and 50 vertical layers during 1980–201854. The air temperature data was obtained from the National Centers for the Environmental Prediction–National Center for the Atmospheric Research (NCEP–NCAR) reanalysis 1 during 1958–2022 with horizontal resolutions of 2.5° × 2.5° and 17 vertical layers55. All datasets were interpolated onto a horizontal grid of 1° × 1° to enable comparison among datasets.

Statistical methods and definitions of indices

Anomalies for all variables were calculated as departures from the monthly climatology unless specified otherwise. Statistical significance tests were performed based on the two-tailed Student’s t test with n−2 degrees of freedom, where n is the sample size. The qualitative conclusions for the significance remain consistent when evaluated using the non-parametric Mann-Kendall test56,57. The thermocline depth was identified as the depth of the 20 °C isotherm. The qualitative conclusion in Fig. 3a, b remains similar based on the thermocline depth defined by the maximum vertical temperature gradient. The zonal SST gradient in the tropical Pacific was defined as the temperature difference between the western Pacific (5°S–5°N, 140°E–170°E, indicated by the left box in Fig. 1b) and the eastern Pacific (5°S–5°N, 190°W–270°W, indicated by the right box in Fig. 1b). The IPO index was calculated based on the difference between the SST anomalies averaged over the central equatorial Pacific (10°S–10°N, 170°E–90°W) and the average of the SST anomalies in the northwest (25°N–45°N, 140°E–145°W) and southwest Pacific (50°S–15°S, 150°E–160°W) following Henley et al.18. Then a 13-year low-pass filter based on Fast Fourier Transform was applied to extract the decadal-scale component of IPO variability. Trends evaluated over time periods in which the IPO phases vary can be influenced by the IPO. To assess the IPO’s contribution to the 43-year trends and 65-year trends of SST in the historical periods (Fig. 3), we regress the detrended SST against the IPO index and then multiply this by the IPO index’s linear trend for the corresponding time period. Besides, we calculate the IPO-related trends in ocean currents and Ekman pumping during 1980–2022 by regressing the detrended variables against the IPO index and then multiplying this by the IPO index’s linear trend for this period.

Reduced gravity system linking SSH and thermocline depth to surface wind stress

A 1.5-layer linear steady state reduced-gravity system on an equatorial \(\beta\)-plane (\(f=\beta y\), in which \(f\) the Coriolis parameter and \(\beta=\) 2.3\( \, \, * \, \, \)10−11 m−1s−1) is used to relate the changes in the surface wind stress to changes in the SSH and thermocline depth. Denote the wind stress by \(\tau=({\tau }^{x},\,{\tau }^{y}).\,\)Specifying a spatially-uniform climatological upper layer thickness (\(\bar{h}=\)150 m)37,38,58,59 and taking \(\Delta \rho=\,2.7\) kg/m3 as the density contrast between upper and bottom layers yields a first baroclinic mode gravity wave speed of c ~ 2.0 m/s, where c2 = \({g}^{{\prime} }\bar{h}\), \({g}^{{\prime} }=g\frac{\Delta \rho }{{\rho }_{0}\,},\) and \({\rho }_{0}=\,1025\) kg/m3 is the reference density. The governing equations on an equatorial \(\beta\)-plane are:

in which \({h}\) is the upper layer thickness between SSH (\({h}_{1}{\rm{;m}}\)) and thermocline depth \(({h}_{2}{\rm{;m}}),\) \(r=\) 1/5.5 year−1 is the damping coefficient, \(U={\int }_{{h}_{1}}^{{h}_{2}}{udz}\,\)(\(u\) the zonal current; m/s), and \(V={\int }_{{h}_{1}}^{{h}_{2}}{vdz}\) (\(v\) the meridional current; m/s). Cross-differentiating Eq. (1–2) and using Eq. (3), we obtain:

Let \(\lambda=\frac{\beta {y}^{2}r}{{g}^{{\prime} }\bar{h}}\) and \(B=\frac{y}{{{\rho }_{0}g}^{{\prime} }\bar{h}}(\frac{{\tau }^{x}}{y}+\frac{\partial {\tau }^{y}}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial {\tau }^{x}}{\partial y})=\frac{f}{{{\rho }_{0}g}^{{\prime} }\bar{h}}{curl}(\frac{\tau }{f}),\,\)

Equation (4) can be solved as:

in which \({x}_{e}\) indicates the eastern boundary, \({h}_{e}\) the layer thickness at the eastern boundary. The change in the SSH can then be directly linked to the change in the surface wind stress if the change of SSH near the eastern boundary is neglected (which is approximately justified on the basis of the changes in Fig. 3):

Estimation of geostrophic zonal current and Ekman pumping

The geostrophic component of the surface current can be determined by considering the balance between the Coriolis force and the pressure gradient force. The geostrophic zonal current \(({u}_{g})\) outside of the equatorial region is expressed as:

At the equator where \(f=0\), an estimate of the equatorial semi-geostrophic zonal current (\({u}_{{sg}}\)) is derived by calculating the second derivative of the SSH on an equatorial \(\beta\)-plane:

which are suggested to be in good agreement with measured velocities60,61.

Following the approach of Zebiak and Cane59, the Ekman transport (\({U}_{E},\,{V}_{E}\)) in the tropical region is formulated by incorporating a frictional component as:

where \({r}_{s}\) indicates the surface layer friction coefficient (1/2 day−1). The Ekman transport away from the equator is consistent with classical Ekman theory. At the equator where \(f=0\), the friction allows an Ekman transport in the direction of the wind stress. Ekman pumping velocity (\({w}_{E}\)) is thus derived from the divergence of the Ekman transport:

Mixed layer heat budget analysis for the long-term SST Change

The heat budget for the mixed layer temperature62 can be expressed as

in which \(a\) denotes anomaly and \(c\) denotes climatology. The heat budget terms include changes in the mean current (\({UaTc}\), \({VaTc}\), \({WaTc}\)), changes in the mean temperature gradient (\({UcTa}\), \({VcTa}\), \({WcTa}\)), and their nonlinear interaction (\({UaTa}\), \({VaTa}\), \({WaTa}\)). The zonal advection and meridional advection terms were averaged over a uniform mixed layer depth of 50 m. The vertical velocity was calculated at the bottom of the mixed layer, and the vertical advection between the 50–100 m and the upper 50 m layers was calculated only in the presence of upwelling. The residual term (\(R\)) for the mixed layer indicates the surface heat flux and subgrid/submonthly processes.

To evaluate the heat budget related to the PCC-related temperature changes, we identified two sub-periods during 1958–2022: the first 20 years (1958–1977) as a reference period, and the most recent 20 years (2003–2022) as the period of climate change. We then calculated the averages of each heat budget term in the quasi-equilibrium period P1 and climate change period P2 based on Eq. (12), and estimated the contributions of each term to the observed temperature changes by calculating their differences:

To reflect the contributions of these terms to the temperature change over each decade, we normalized their units to °C/month per decade by dividing by a factor of 6.5. In addition, to analyze the IPO’s impact on the temperature change on decadal timescales, the detrended heat budget terms were regressed against the IPO index. The regression coefficients were then scaled by the linear trend in the IPO index from 1980 to 2022.

Data availability

The datasets used to reproduce the results of this paper are located at https://metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html (HadISST data), https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html (ERSSTv5), https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.kaplan_sst.html (Kaplan data) https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cobe.html (COBE data), https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-oras5?tab=overview (ORAs5 data), https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/SOURCES/.CARTON-GIESE/.SODA/.v2p2p4/.temp/ (SODA2.2.4 data), https://www2.atmos.umd.edu/~ocean/index_files/soda3.3.2_mn_download.htm (SODA3.3.2 data), and https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis.html (NCEP–NCAR data).

Code availability

The analysis scripts used to generate the figures are available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27018271.

References

Cane, M. A. et al. Twentieth-Century sea surface temperature trends. Science 275, 957–960 (1997).

Zhang, W., Li, J. & Zhao, X. Sea surface temperature cooling mode in the Pacific cold tongue. J. Geophys. Res. 115, 2010JC006501 (2010).

Karnauskas, K. B., Seager, R., Kaplan, A., Kushnir, Y. & Cane, M. A. Observed strengthening of the Zonal Sea surface temperature gradient across the equatorial Pacific Ocean. J. Clim. 22, 4316–4321 (2009).

Solomon, A. & Newman, M. Reconciling disparate twentieth-century Indo-Pacific ocean temperature trends in the instrumental record. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 691–699 (2012).

Seager, R. et al. Strengthening tropical Pacific zonal sea surface temperature gradient consistent with rising greenhouse gases. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 517–522 (2019).

Seager, R., Henderson, N. & Cane, M. Persistent discrepancies between observed and modeled trends in the tropical Pacific Ocean. J. Clim. 35, 4571–4584 (2022).

Knutson, T. R. & Manabe, S. Time-Mean response over the tropical Pacific to increased CO2 in a coupled ocean-atmosphere model. J. Clim. 8, 2181–2199 (1995).

Meehl, G. A. & Washington, W. M. El Niño-like climate change in a model with increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Nature 382, 56–60 (1996).

Watanabe, M., Dufresne, J.-L., Kosaka, Y., Mauritsen, T. & Tatebe, H. Enhanced warming constrained by past trends in equatorial Pacific sea surface temperature gradient. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 33–37 (2021).

Olonscheck, D., Rugenstein, M. & Marotzke, J. Broad consistency between observed and simulated trends in sea surface temperature patterns. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086773 (2020).

Wengel, C. et al. Future high-resolution El Niño/Southern Oscillation dynamics. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 758–765 (2021).

Yeager, S. G. et al. Reduced Southern Ocean warming enhances global skill and signal-to-noise in an eddy-resolving decadal prediction system. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 107 (2023).

Meehl, G. A., Teng, H. & Arblaster, J. M. Climate model simulations of the observed early-2000s hiatus of global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 898–902 (2014).

Coats, S. & Karnauskas, K. B. Are simulated and observed twentieth century tropical pacific sea surface temperature trends significant relative to internal variability? Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9928–9937 (2017).

Deser, C., Phillips, A. S. & Alexander, M. A. Twentieth century tropical sea surface temperature trends revisited. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 2010GL043321 (2010).

Dong, L. & Zhou, T. The formation of the recent cooling in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the associated climate impacts: A competition of global warming, IPO, and AMO. JGR Atmospheres 119, 11–272 (2014).

Hansen, J. et al. Forcings and chaos in interannual to decadal climate change. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 25679–25720 (1997).

Henley, B. J. et al. Spatial and temporal agreement in climate model simulations of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 044011 (2017).

Mantua, N. J., Hare, S. R., Zhang, Y., Wallace, J. M. & Francis, R. C. A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 78, 1069–1079 (1997).

Power, S., Casey, T., Folland, C., Colman, A. & Mehta, V. Inter-decadal modulation of the impact of ENSO on Australia. Clim. Dyn. 15, 319–324 (1999).

Zhang, Y., Wallace, J. M. & Battisti, D. S. ENSO-like Interdecadal Variability: 1900–93. J. Clim. 10, 1004–1020 (1997).

Wang, B., Liu, J., Kim, H.-J., Webster, P. J. & Yim, S.-Y. Recent change of the global monsoon precipitation (1979–2008). Clim. Dyn. 39, 1123–1135 (2012).

Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Recent global-warming hiatus tied to equatorial Pacific surface cooling. Nature 501, 403–407 (2013).

Meehl, G. A., Hu, A., Santer, B. D. & Xie, S.-P. Contribution of the interdecadal Pacific Oscillation to twentieth-century global surface temperature trends. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1005–1008 (2016).

Zuo, H., Balmaseda, M. A., Tietsche, S., Mogensen, K. & Mayer, M. The ECMWF operational ensemble reanalysis–analysis system for ocean and sea ice: a description of the system and assessment. Ocean Sci. 15, 779–808 (2019).

Kang, S. M., Ceppi, P., Yu, Y. & Kang, I.-S. Recent global climate feedback controlled by Southern Ocean cooling. Nat. Geosci. 16, 775–780 (2023).

Kang, S. M. et al. Global impacts of recent Southern Ocean cooling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2300881120 (2023).

Bjerknes, J. Atmospheric teleconnections from the equatorial Pacific. Mon. Wea. Rev. 97, 163–172 (1969).

Wyrtki, K. El Niño—the dynamic response of the equatorial Pacific Ocean to atmospheric forcing. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 5, 572–584 (1975).

Rebert, J. P., Donguy, J. R., Eldin, G. & Wyrtki, K. Relations between sea level, thermocline depth, heat content, and dynamic height in the tropical Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 90, 11719–11725 (1985).

Bamber, J. L., Westaway, R. M., Marzeion, B. & Wouters, B. The land ice contribution to sea level during the satellite era. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063008 (2018).

Wigley, T. M. L. & Raper, S. C. B. Thermal expansion of sea water associated with global warming. Nature 330, 127–131 (1987).

Timmermann, A., McGregor, S. & Jin, F.-F. Wind effects on past and future regional sea level trends in the Southern Indo-Pacific. J. Clim. 23, 4429–4437 (2010).

Merrifield, M. A. A shift in western tropical Pacific sea level trends during the 1990s. J. Clim. 24, 4126–4138 (2011).

Marcos, M. & Amores, A. Quantifying anthropogenic and natural contributions to thermosteric sea level rise. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2502–2507 (2014).

McGregor, S., Gupta, A. S. & England, M. H. Constraining wind stress products with sea surface height observations and implications for Pacific Ocean Sea level trend attribution. J. Clim. 25, 8164–8176 (2012).

Veronis, G. Model of world ocean circulation: I. Wind-driven, two-layer. J. Mar. Res. 31, 228–288 (1973).

Sarachik, E. S. & Cane, M. A. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation Phenomenon (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Manabe, S. & Wetherald, R. T. The effects of doubling the CO2 Concentration on the climate of a General circulation model. J. Atmos. Sci. 32, 3–15 (1975).

Fu, Q., Manabe, S. & Johanson, C. M. On the warming in the tropical upper troposphere: Models versus observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 2011GL048101 (2011).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Atlantic and Pacific tropics connected by mutually interactive decadal-timescale processes. Nat. Geosci. 14, 36–42 (2021).

McGregor, S. et al. Recent Walker circulation strengthening and Pacific cooling amplified by Atlantic warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 888–892 (2014).

Luo, J.-J., Sasaki, W. & Masumoto, Y. Indian Ocean warming modulates Pacific climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18701–18706 (2012).

Dong, Y., Armour, K. C., Battisti, D. S. & Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E. Two-Way teleconnections between the Southern Ocean and the Tropical Pacific via a Dynamic Feedback. J. Clim. 35, 6267–6282 (2022).

He, C. et al. Tropical Atlantic multidecadal variability is dominated by external forcing. Nature 622, 521–527 (2023).

Deser, C. & Phillips, A. S. Spurious Indo‐Pacific connections to internal Atlantic Multidecadal variability introduced by the global temperature residual method. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL100574 (2023).

Fenske, T. & Clement, A. No internal connections detected between low frequency climate modes in North Atlantic and North Pacific Basins. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL097957 (2022).

Rayner, N. A. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Ishii, M., Shouji, A., Sugimoto, S. & Matsumoto, T. Objective analyses of sea‐surface temperature and marine meteorological variables for the 20th century using ICOADS and the Kobe Collection. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 865–879 (2005).

Kaplan, A. et al. Analyses of global sea surface temperature 1856–1991. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 18567–18589 (1998).

Vidard, A., Bouttier, P.-A. & Vigilant, F. NEMOTAM: tangent and adjoint models for the ocean modelling platform NEMO. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 1245–1257 (2015).

Carton, J. A. & Giese, B. S. A reanalysis of ocean climate using Simple Ocean Data Assimilation (SODA). Monthly Weather Rev. 136, 2999–3017 (2008).

Carton, J. A., Chepurin, G. A. & Chen, L. SODA3: a new ocean climate reanalysis. J. Clim. 31, 6967–6983 (2018).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-Year Reanalysis Project. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 77, 437–471 (1996).

Kendall, M. G. Rank Correlation Methods (Charles Griffin, London, 1975).

Mann, H. B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica. 13, 245–259 (1945).

Zebiak, S. E. Tropical Atmosphere–Ocean Interaction and the El Niño/Southern Oscillation Phenomenon (Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 260 pp., 1985).

Zebiak, S. E. & Cane, M. A. A Model El Niño–Southern Oscillation. Mon. Wea. Rev. 115, 2262–2278 (1987).

Moore, D. W. H. & Philander, S. G. H. Modeling of the tropical oceanic circulation (Wiley, New York, 1977).

Picaut, J., Hayes, S. P. & McPhaden, M. J. Use of the geostrophic approximation to estimate time‐varying zonal currents at the equator. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 3228–3236 (1989).

Jin, F., An, S., Timmermann, A. & Zhao, J. Strong El Niño events and nonlinear dynamical heating. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1120 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Chia-Ying Lee for useful suggestions on how best to present the main points of this manuscript. NSF award OCE-2219829 (F.J., R.S., M.A.C.) NSF award AGS-2217618 (R.S.) NSF award AGS-2101214 (R.S.) DESC0023333 (R.S.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.J., R.S., M.A.C. Methodology: F.J., R.S., M.A.C. Investigation: F.J. Visualization: F.J. Supervision: R.S. Writing—original draft: F.J. Writing—review & editing: R.S., M.A.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, F., Seager, R. & Cane, M.A. A climate change signal in the tropical Pacific emerges from decadal variability. Nat Commun 15, 8291 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52731-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52731-6

This article is cited by

-

The expanding Indo-Pacific freshwater pool and changing freshwater pathway in the South Indian Ocean

Nature Climate Change (2026)

-

Unraveling the interactions between tropical Indo-Pacific climate modes using a simple model framework

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Reversed tropical-Arctic teleconnection under climate change

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Decelerated Arctic Sea ice loss triggered by accelerated North Pacific warming over the past decade

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Contrasting historical trends of atmospheric rivers in the Northern Hemisphere

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)