Abstract

Coherent dispersive wave emission, as an important phenomenon of soliton dynamics, manifests itself in multiple platforms of nonlinear optics from fibre waveguides to integrated photonics. Limited by its resonance nature, efficient generation of coherent dispersive wave with ultra-broad bandwidth has, however, proved difficult to realize. Here, we unveil a new regime of soliton dynamics in which the dispersive wave emission process strongly couples with the splitting dynamics of the driving pulse. High-order dispersion and self-steepening effects, accumulated over soliton self-compression, break the system symmetry, giving rise to high-efficiency generation of coherent dispersive wave in the ultraviolet region. Simultaneously, asymmetric soliton splitting results in the appearance of a temporally-delayed ultrashort pulse with high intensity, overlapping and copropagating with the dispersive wave pulse. Intense cross-phase modulations lead to octave-wide broadening of the dispersive wave spectrum, covering 200–400 nm wavelengths. The highly-coherent, octave-wide ultraviolet spectrum, generated from the simple capillary fibre set-up, is in great demand for time-resolved spectroscopy, ultrafast electron microscopy and frequency metrology applications, and the critical role of the secondary pulse in this process reveals some new opportunities for all-optical control of versatile soliton dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Temporal solitons in optical waveguides, originated from dynamical balancing between Kerr nonlinearity and chromatic dispersion1,2, underlie a rich variety of phenomena in nonlinear optics. Some key examples include ultrashort pulse self-compression3,4,5, efficient light conversion over a large wavelength range5,6,7,8,9,10,11, and multi-octave-spanning supercontinuum generation12,13,14,15,16,17. Among them, the phenomenon of resonant dispersive wave (DW) emission18,19,20,21, also known as optical Cherenkov radiation20, has been at the focus of attention across multiple platforms of nonlinear optics, from optical fibre waveguides5,9,10,11,12,13,14 to integrated photonics chips15,22. Through introducing higher-order (> 2nd order) dispersion effects, the otherwise symmetric dispersion landscape of an optical waveguide is modulated, leading to the appearance of additional zero group-velocity-dispersion (GVD) points. This modulation also gives birth to phase-matched wavelengths in the normal GVD regime of the waveguide, coherently linked to the soliton (pump) wavelength in the anomalous regime18,19,20,21. In such an optical waveguide, spectral spreading of a high-order soliton over propagation could enable, through the cascaded four-wave mixing21, efficient energy conversion from the pump pulse to a packet of quasi-linear optical waves at the phase-matched wavelength. This phenomenon of coherent DW emission has facilitated the generation of octave-spanning supercontinuum12,13,14,15,16, which is a critical pre-requisite of the f-2f self-referencing technique for optical frequency comb generation23,24. Moreover, coherent DW emission has also been investigated in a variety of nonlinear optical systems based on multi-mode fibres25,26, hollow-core fibres5,9,10,11,12,13,27,28,29 and integrated silica or silica nitride waveguides15,30,31, highlighting the importance of this nonlinear laser-frequency-conversion mechanism for extending the wavelength accessibility of ultrafast light sources, towards both ultraviolet (UV)5,9,10,11,12,13 and mid-infrared15,27.

Because of the intrinsic nature of phase matching21, the manifestation of DW emission in these aforementioned systems is commonly observed as resonant spikes on the soliton spectrum5,9,10,11. This narrow-band feature of DW emission restricts, to some extent, the spectral coverage and therefore the ultrafast performance of DW pulses. Some attempts for broadening DW spectra, based on some mechanisms such as soliton-trapping32,33, Raman nonlinearity12 or photoionization effect13, have been reported in literatures. Yet, the realization of coherent DW emission with simultaneously high conversion efficiency and ultra-broad spectral coverage, supporting the formation of high-energy, single-cycle or even sub-cycle pulses, remains to be a long-standing challenge for many years.

In this article, we present a unique regime of nonlinear soliton dynamics, obtained in a gas-filled hollow capillary fibre (HCF), that involves a delicate coupling between UV DW emission and soliton splitting effects. In the nonlinear dynamics, the self-steepening-induced blue-shift of the pump pulse, accumulated over the soliton self-compression process, enhances the radiation efficiency of the short-wavelength DW34. Then, the generated UV DW pulse, after a short length of propagation in the capillary fibre, interacts intensely with a secondary pulse which stems from the asymmetric splitting process of the pump pulse. With a few-femtosecond pulse width, the secondary pulse has a high peak intensity comparable to that of the self-compressed main pulse, strongly modulating the UV DW. As shown in the following, this delicate coupling leads to spectral broadening of the DW pulse by nearly one order of magnitude, giving rise to the generation of octave-wide UV spectrum in this capillary fibre set-up, with good spectral stability, high phase coherence and some wavelength tunability. This work extends our knowledge on interactions between soliton and DW, and further highlights the versatility of nonlinear soliton dynamics in optical waveguides.

Results

Broadband ultraviolet DW generation

The gas-filled capillary fibre set-up, used to perform the experiments, is sketched in Fig. 1a (see Methods below and Supplementary note 1 for more details of the set-up). The silica-glass capillary has a length of 42 cm and an inner diameter of 100 μm. When filled with monatomic (Raman inactive) gas of Ne, the dispersion landscape of this capillary waveguide can be adjusted through varying the gas pressure5,9,10,11. At a gas pressure of 5 bar, the zero GVD point of the waveguide is at 520 nm. In this condition, the waveguide exhibits an anomalous GVD value of −4.0 × 10−2 ps2/km at the pump wavelength of 781 nm, while the phase-matching wavelength of the DW emission35 (when neglecting the nonlinearity term in the formula) can be calculated to be ~262 nm, see Fig. 1a.

a Broadband UV DW generation mechanism in Ne-filled HCF. At a gas pressure of 5 bar, the zero-dispersion wavelength (ZDW) is 520 nm. The dynamics of soliton self-compression, UV DW emission, cross-phase modulation (XPM) caused by soliton-splitting effect, and octave-wide broadening of DW spectrum are illustrated at the bottom. b, c Measured and simulated spectra when pumped at 10 fs, 26 μJ, 766 nm (N = 3.9) (b) and 18 fs, 64 μJ, 781 nm (N = 7.8) (c). The HCF used in the experiment has a length of 42 cm and a core diameter of 100 μm and filled with 5 bar Ne gas. d Near-field beam profiles of UV DW at different wavelengths, measured using a CCD camera.

In the experiment, we obtained significantly-different DW spectra (see Methods below) at the output port of the capillary fibre, when using different pump pulse parameters, as illustrated in Fig. 1b, c. When the 10-fs pump pulse with an energy of 26 μJ (corresponding to a soliton order of 3.9) was used, typical resonance-shaped DW spectrum was observed with a full-width-half-maximum (FWHM) spectral bandwidth of ~20 nm (see Fig. 1b). In this case, the energy fraction of the UV DW energy in the output spectrum is measured to be ~6.8%. A much broader DW spectrum, covering the entire 200–400 nm UV region (within 13 dB spectral density scale), could be obtained (see Fig. 1c) as we altered the pump pulse parameters to 18 fs and 64 μJ, corresponding to a higher soliton order of 7.8. This octave-spanning UV DW, measured at the fibre output port, has an energy fraction of ~15.5% and exhibits perfect single-fundamental-mode purity over its entire spectral range. Near-field beam profiles of the broadband DW were measured at several wavelengths, using narrow-band optical filters and an UV charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera, see Fig. 1d (see also Methods below).

These experimental results of both narrow- and broad-band UV DW emission processes can be quantitively reproduced using both the generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation (GNLSE)36 or the single-mode unidirectional pulse propagation equation (UPPE)37,38,39, see Fig. 1b, c (see also Methods below). We found that the numerical results of nonlinear pulse propagation processes in the capillary fibre, simulated using these two models, exhibit excellent agreement with each other, verifying the validity of the GNLSE model in the few-cycle regime9,36,40. See Supplementary note 2 for detailed discussions. The system parameters used in the simulations were exactly the same as these in the experiments (see Fig. 1), and the temporal profile of the pump pulse used in the simulation comes from the experimental results measured using the frequency-resolved optical gating (FROG) set-up, see more details in Supplementary note 6. The GNLSE used in the simulation can be expressed as

where A is the complex amplitude of the light field in time domain, \({\beta }_{n}\) the nth-order dispersion of the fibre waveguide, T the time in a reference frame moving at the group velocity \(1/{\beta }_{1}\), \(\gamma\) the nonlinear parameter, \({\omega }_{0}\) the central frequency of the driving pulse, and \(\alpha\) the wavelength-dependent fibre loss. In the simulation, we used the actual dispersion curve (over the wavelength range of 100 nm–4000 nm) calculated using the HCF model41, which includes high-order dispersion terms. The dispersion information of the gas material is from the standard database42. Detailed descriptions on the dispersion and loss performances of the gas-filled HCF waveguide are presented in Methods below. In the left side of Eq. (1), the Kerr nonlinearity and 2nd-order dispersion terms describe the propagation of canonical solitons, while in the right side of the equation, three terms are included, describing respectively higher-order dispersion, self-steepening effect, and wavelength-dependent capillary loss. All of these three terms could be regarded as some perturbations to propagation processes of canonical solitons which (without these perturbations) exhibit perfect symmetry in both spectral and temporal domains36,43. Note that we do not consider the Raman term in Eq. (1), since the Ne gas used in the experiment is Raman-inactive. Moreover, in the numerical simulation we found that the peak intensity of the pump pulse in the capillary fibre is always far below the photoionization threshold of the Ne gas, and therefore the photoionization effect could be neglected in our simulations without leading to any significant influence on the results. See more details in Supplementary note 2.

As conceptually illustrated in Fig. 1a, the first stage of propagation of the pump pulse in the capillary roughly follows the high-order soliton propagation process governed by the nonlinear Schrödinger equation1,36,43, leading to soliton self-compression. This is because at this beginning stage, the relatively-narrow pulse spectrum (long pulse duration) leads to relatively-weak high-order effects. However, the soliton self-compression results in significant broadening of the pulse spectrum and increased pulse peak power, enhancing higher-order effects as described in the right side of Eq. (1). The first obvious consequence resulting from these high-order effects is the emission of phase-matched UV DW18,19,20,21, which can be further enhanced through blue shifting of the pump pulse due to self-steepening nonlinearity34. The DW has generally a narrow-band spectrum, limited by the phase matching nature of its emission process21. After being generated, the DW pulse has a lower group velocity than the soliton, and therefore moves gradually behind the pump pulse.

Near the maximum self-compression point, strong high-order effects (perturbations) could also cause the highly-asymmetric splitting of the high-order soliton18,19,44,45, leading to the appearance of the secondary pulse just behind the main pulse (with a short temporal delay), see Fig. 1a. In principle, we could adjust the relative intensity and temporal position of this secondary pulse through varying the pulse width and soliton order of the pump pulse18,19,44,45, so as to enable perfect overlapping and strong interactions between the secondary pulse and the DW. Significant spectral broadening of the UV DW could therefore be obtained through intense cross-phase modulations (XPMs), see Fig. 1a.

Spectrogram analysis

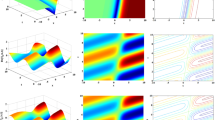

To better illustrate the complex soliton dynamics, we performed deliberately numerical studies based on the spectrogram-analysis method. The simulation results and our analyses are shown in Fig. 2, see also Supplementary Movie 1 and Movie 2. While the simulated evolution dynamics of the 18 fs, 64 μJ, 781 nm pump pulse (soliton order N = 7.8) inside the capillary fibre are illustrated in the right column of Fig. 2 (Fig. 2e–h), the evolution dynamics of the 10 fs, 26 μJ, 766 nm pulse (soliton order N = 3.9) in the capillary fibre are also illustrated in the left column (Fig. 2a–d) for a direct comparison. In the simulation, the temporal profiles of the pump pulse (plotted as red lines in Fig. 2) are obtained through using an ideal (chirp-free) square-shaped filter with a transmission window covering 400–4000 nm, while the temporal profiles of the DW pulse (plotted as blue shadows) are obtained using another ideal filter covering 100–400 nm. It can be found that at a moderate soliton order of 3.9 (left column of Fig. 2), soliton self-compression results in a strong spectral broadening of the pump pulse. Near the maximum compression point (L = 28 cm, see Fig. 2b), the phenomenon of narrow-band DW emission (marked with I in Fig. 2) is clearly observed at the phase-matching wavelength of 261 nm (see purple line in Fig. 2b). After this maximum compression point, the peak power of the pump pulse decreases gradually over propagation (see Fig. 2c, d), without observing soliton splitting phenomenon. The generated DW pulse gradually moves behind the pump pulse due to its lower group velocity, and its temporal stretching is due to normal dispersion of the capillary waveguide at the phase-matching wavelength of ~250 nm (see purple lines in Fig. 2c, d).

Simulated evolution dynamics of the 10 fs, 26 μJ, 766 nm pulse (N = 3.9) (a–d) and the 18 fs, 64 μJ, 781 nm pulse (N = 7.8) (e–h), with the same simulation parameters as Fig. 1b, c. a, e Simulated spectral evolution of the pulse as a function of fibre length. b–d, f–h Spectrogram analysis of the pulse at the indicated positions in the HCF. I – Narrow-band DW emission, II – asymmetric soliton splitting phenomenon, III – spectral broadening of the UV DW through XPM effect. Through using the ideal filters with transmission windows covering 400–4000 nm and 100–400 nm, the temporal profiles of the pump pulse and DW were obtained, respectively, which were plotted as red lines and blue shadows. The black lines indicate the pulse spectra at different fibre positions. The purple lines indicate the phase-matching wavelength of DW emission, and \(\varDelta {{{\rm{n}}}}\) represents the nonlinear refractive index caused by the pump pulse.

As illustrated in the right column of Fig. 2, a higher soliton order of 7.8 can lead to a dramatic change of the nonlinear pulse-evolution dynamics, especially near and after the maximum compression point (L ≥ 34 cm, see Fig. 2f–h). The higher peak power of the compressed pulse results in stronger higher-order nonlinear effects (in the right side of Eq. (1)) accumulated over the soliton self-compression process, which, through collaborating with higher-order dispersion effects, leads to highly-asymmetric soliton splitting phenomenon18,19 (marked with II in Fig. 2). See more detailed results and discussions in Supplementary note 4 and Supplementary Movies 3–7. It can be found in Fig. 2f that the asymmetric soliton splitting gives birth to a secondary pulse which, in the simulation, is around 4 fs behind the main pulse. As illustrated in Fig. 2g, the intensity of this secondary pulse increases gradually over propagation, and its peak power reaches to ~1.6 GW at L = 38 cm where it has the largest overlapping with the UV DW pulse. Strong XPMs cause obvious spectral broadening of the UV DW36,46,47, marked with III in Fig. 2h. The leading edge of DW pulse moves to the longer wavelengths (red shift) due to a positive slope of the index modulation, while light components at the trailing edge of the DW pulse moves to the shorter wavelength (blue shift) due to a negative slope.

As illustrated in Fig. 2h, at the trailing edge of the DW pulse, the blue-shifting components have even lower group velocities than the pump pulse, thus quickly moving away from the secondary pulse. The increased walking-off effect restricts further broadening of the DW spectrum towards even shorter wavelengths. On the contrary, the red-shifting components at the leading edge accelerate due to normal waveguide dispersion, which strengthens the interaction between the two pulses and therefore enhances the red-shifting effect of the DW spectrum. This mechanism, concerning acceleration and deceleration of different DW components, can be used to explain some critical spectral features (observed in the experiments) of this broadband DW, including the formation of M-shaped spectrum and its obvious spectral asymmetry biased to the longer wavelengths (see Figs. 1c, 3).

a Experimental spectral evolution at the output of the 42 cm-long HCF with 100 μm core diameter filled with 5 bar Ne gas for 18 fs pump pulses as a function of pump pulse energy. b Corresponding numerical results. The black dashed line indicates the phase-matching DW wavelength with considering the nonlinearity term. c Several examples of experimental (blue shadows) and simulated (red lines) spectral evolution of DW at pump pulse energies from 48 μJ to 64 μJ, corresponding to the purple dashed frames in (a, b). The results in (c) are also plotted on a liner scale, see Supplementary Fig. S19. The DW spectral bandwidth adjustments at 6 bar and 7 bar Ne gas are shown in Supplementary Fig. S16.

In Fig. 2, we also plot the phase-matching wavelength of the DW emission (marked as purple lines) as the function of propagation distance. It can be found that as the peak power of the pump pulse changes over propagation, the phase-matching wavelength of DW emission varies merely by < 25 nm. For N = 3.9 case, the phase-matching wavelength varies gradually from ~261 nm to ~247 nm (see Fig. 2a–d), for N = 7.8 case, the phase-matching wavelength varies from ~255 nm to ~242 nm (see Fig. 2e–h). These results indicate clearly that the octave-wide spectral broadening of the generated DW can not be attributed to the phase-matching wavelength variation over pulse propagation.

In order to further verify that the formation of ultra-broadband DW spectrum results from the XPM effect of the secondary pulse generated from soliton splitting, we have made some quantitative analyses on the frequency variations of the generated DW, which can be regarded as direct consequences of the time dependence of the XPM-induced nonlinear phase shifts. See Supplementary note 5 for more details. In these analyses, we can calculate that the accumulated XPM-induced frequency shifts of the DW, over co-propagating in the HCF (from 38 cm to 42 cm in Fig. 2e), are 0.19 PHz (toward the higher frequency side) at the trailing edge of the secondary soliton and −0.24 PHz (toward the lower frequency side) at its leading edge. These calculated results exhibit striking agreement with our experimental observations shown in Fig. 3c and Fig. S17 at the input pulse energy of 64 μJ (N = 7.8).

Note that in the Fig. 2a, e, we found some faint spectral lines at wavelengths of ~255 nm and ~260 nm before the maximum compression point. Such spectral lines are recognized as the third-harmonic (TH) signal of the pump pulse, which can be frequently observed in numerical simulations of ultrafast pulse propagation using the UPPE model37,38,39. The amplitude of the TH light is around two orders of magnitude lower than that of the generated DW. See some detailed discussions and simulations in Supplementary note 2. It can be found in Fig. 2e that the soliton exhibits a phenomenon of spectral red-shift during the DW emission process. This phenomenon could most probably be attributed to the spectral recoil effect7,48, which can be largely enhanced at higher soliton orders due to stronger DW emission processes with higher efficiencies.

In addition, we found in the simulation that slight change of the pump-pulse shape has little impact on the nonlinear pulse-propagation dynamics. For example, we performed simulations using Gaussian- and Sech-shaped pump pulses with similar energies and temporal widths as these shown in Fig. 1c, and observed very similar broadband DW generation processes for both of the two pulse shapes, see more details in Supplementary note 3 and Supplementary Movie 3.

Adjustment of UV DW spectrum

The spectral bandwidth of the UV DW can be adjusted simply through varying the pump pulse energy launched into the capillary fibre. In the experiment, we gradually decreased the energy of 18-fs pump pulse from 64 μJ to 4 μJ, and measured the output spectrum at the fibre output port. The experimental results are illustrated in Fig. 3a. For a comparison, numerical simulations are illustrated in Fig. 3b, and excellent agreement is found between the experimental and numerical results. Several typical examples at pulse energies from 48 μJ to 64 μJ, corresponding to soliton orders from 6.7 to 7.8, are plotted in Fig. 3c. It can be found that at a higher soliton order, stronger broadening effect of the UV DW spectrum could be obtained, which is mainly attributed to an increased energy (and therefore a higher peak power) of the secondary pulse generated in the soliton splitting process.

Coherence and stability characterizations

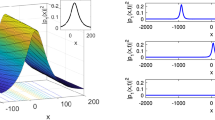

The phase profile and coherence performance of the generated DW were investigated numerically. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the broadband DW exhibits a smooth spectral phase profile at the output port of the fibre. We also simulated the influence of quantum noise on the broadband DW emission process, and estimated the degree of first-order coherence43,49,50 on the broadband DW spectrum (see Methods below). The results (see Fig. 4a) show that the generated DW has good coherence over its broad spectrum. In the simulation, we found that the chirp of the output DW pulse (see Fig. 4b) could be well compensated through introducing −2 fs2 group delay dispersion (GDD) to the pulse. As illustrated in Fig. 4c, the compressed pulse has a FWHM width of 1.3 fs, which is quite close to its Fourier-transform-limit (FTL) value (1.2 fs).

a Simulated phase profile (purple line) and complex degree of first-order coherence (yellow line) of the broadband UV DW. The measured (blue shadow) and simulated (red line) DW spectra are plotted on a linear scale, corresponding to the case at the pump pulse energy of 64 μJ in Fig. 3. b, c Corresponding numerical simulations of the normalized temporal envelope (red lines), electrical field intensity |E | 2 (blue lines) and phase profiles (purple lines). (c) is the compressed pulse through introducing −2 fs2 group delay dispersion to the output DW pulse (b).

At a pump pulse energy of 64 μJ, the pulse energy of the broadband UV DW was experimentally measured to be 4.07 μJ (see Methods below), corresponding to an overall emission efficiency of ~6.4%. At this pump energy, the output DW exhibits good spectral stability. In the experiment, we measured the broadband DW spectrum for 1000 times with a time interval of 1.8 s and scanning time of 0.1 s, and the results of 30 min recording are plotted in Fig. 5a. We also performed relatively-intensity-noise (RIN) and phase-noise (PN) measurements on the generated broadband UV DW. We found the relatively-intensity variation of the broadband UV DW pulse train is quite small over a short time scale of 100 ms, with a root-mean-square (RMS) value of ~0.4%. The long-term intensity stability of the broadband UV DW was estimated to be ~1.9% (RMS value) over 30 min. We also measured in the experiment the PN spectrum of the broadband UV DW, and the results indicate an upper limit of the timing-jitter value to be ~244 ns (integrated from 2 Hz to 990 Hz). See more details of the RIN and PN measurements in Methods and Supplementary note 7.

a Measured spectral stability of the broadband UV DW over 30-minute recording; gray shadow, 1000 measurement results with a time interval of 1.8 s and scanning time of 0.1 s; cyan line, the mean value of these results. The experimental parameters of pump pulse, HCF and gas are the same as those in Fig. 1c. b Measurred SD-FROG trace. c Retrieved SD-FROG trace with a retrieving error of 0.7%. d Retrieved temporal (red line) and phase (purple line) profiles. The DW pulse shows a temporal width of 3.7 fs. e Retrieved spectral (red line) and phase (purple line) profiles. The experimental spectra are plotted as blue shadow and black line, measured before and after the chirped mirrors, respectively. In (b–e), the experimental parameters correspond to the case at the pump pulse energy of 56 μJ in Fig. 3c.

The good phase coherence and spectral stability of the broadband DW were further verified in the experiments of pulse chirp compensation and temporal width measurement. We constructed a self-diffraction (SD) FROG set-up and mounted it in a gas chamber, see Methods below and Supplementary note 1 for some details of the diagnosis set-up. Two chirp mirrors were used in the chamber to compensate the pulse chirp accumulated over the optical path. When the gas pressure inside the chamber was fixed at 1 bar (atmospheric pressure), the gas type was air-helium mixture. Therefore, we could vary the ratio of helium gas in the mixture to adjust precisely the GDD value in the optical path, so as to minimize the residual pulse chirp at the measurement point. At a pulse energy of 56 μJ, the measured and retrieved FROG traces are illustrated in Fig. 5b–e, with a reasonable FROG retrieving error of ~0.7%. Note that the measured spectrum (plotted as black line) by the FROG set-up is much narrower than the original spectrum (plotted as blue shadow) measured at the output port of the capillary fibre (see Fig. 5e), which is due to the limited bandwidth of the two chirp mirrors (CM313 from Ultrafast Innovations, with a transmission window from 230 nm to 270 nm). The filtered UV spectrum under test has a FWHM bandwidth of ~40 nm, corresponding to a FTL pulse width of 3.2 fs (spectral range within 10-dB intensity). The retrieved FWHM pulse width is 3.7 fs (see Fig. 5d), quite close to this FTL value. Even though the measured UV spectrum is merely a small portion of the generated DW spectrum (see Fig. 5d), the good compensability of the UV output pulse (close to its FTL width) verifies, to some extent, the good coherence and smooth phase of the broadband DW.

Discussion

We found that this spectral broadening phenomenon of DW, induced by soliton splitting dynamics, is generic, which can be observed over a wide range of system parameters. In the experiment, we varied the Ne-gas pressure in the capillary fibre from 3 bar to 7 bar, corresponding to a tuning of the zero GVD wavelength of the waveguide from 460 nm to 564 nm and a tuning of the phase-matching wavelength from 202 nm to 327 nm5,35. Note that the change of gas pressure can also vary Kerr nonlinearity of the waveguide as well as GVD value at the pump wavelength. Experimentally, we fixed the pump pulse width to 18 fs and adjusted accordingly the pump pulse energy, so as to maintain the soliton order to be ~7.8. Continuous central-wavelength tuning of the broadband DW emission was observed in the experiments (see Fig. 6), exhibiting similar tuning abilities as narrow-band DW emission experiments5,9,10,11. Simulation results show that this mechanism of DW broadening is also valid when using a different type of gas in the capillary. For example, when 18-fs, 210-μJ, 800-nm pump pulse (soliton order N = 7.4) was used, the 100-μm-inner-diameter, 35 cm-long capillary, filled with 3.2-bar He gas, could be used to extend the broadband DW emission to the vacuum UV regime, covering 140–240 nm wavelengths. See Supplementary note 8 for some detailed results and discussions.

The broadband DW spectra with different emission wavelengths are measured at different Ne-gas pressure from 3 bar to 7 bar. The pump pulse used in the experiment has a temporal width of 18 fs and the HCF has a length of 42 cm and a core diameter of 100 μm. These results are also plotted on the coordinate axis of spectrum versus frequency, see Supplementary Fig. S17.

Even though interactions between Raman-shifted solitons and short-wavelength DWs have been demonstrated32,33,51 (also known as “soliton trapping effect” observed during the supercontinuum generation process in solid-core photonic crystal fibre), the generation of octave-spanning UV DW with μJ-level pulse energy and good spectral coherence has never been explored before. The extreme spectral broadening due to strong XPMs, can be mainly attributed to two reasons. First, the secondary pulse generated due to soliton splitting dynamics, appears just behind the self-compressed pulse (with merely few-femtosecond temporal delay), and it has a relatively high peak power (see Fig. 2g, h) comparable to that of the self-compressed pulse, strongly enhancing the XPM effect. Second, the short delay time between the self-compressed and the secondary pulses ensures the fact that the UV DW, after being generated, immediately meets with the intense secondary pulse after only a short-length (~4 cm, see Fig. 2f, g) propagation in the capillary waveguide. Therefore, excessive temporal stretching of the DW pulse, due to waveguide dispersion, is efficiently suppressed, leading to a perfect temporal overlapping of the two pulses (see Fig. 2g). In contrast, the soliton trapping effect, demonstrated in supercontinuum generation32,33,51, relies on the deceleration of Raman-frequency-shifted soliton which normally requires more propagation distance. This long-distance (tens of centimetres32,33,51) propagation results in large temporal stretching of the DW, significantly weakening the interaction strength between the two pulses.

Moreover, interactions between the secondary soliton and the generated DW, such as four-wave mixing52,53,54 and nonlinear-event-horizon processes55,56,57, were also observed during the generation of octave-wide spectral broadening of the DW. It can be found in Supplementary Movie 3 that the leading edge of the secondary pulse established a horizon which could result in red-shift and acceleration of some DW components (known as nonlinear event horizon effect55). Nevertheless, the formation of octave-wide spectral broadening of the DW is mainly due to the strong XPM effect, relying on the large overlap and co-propagation of the DW pulse with the high-intensity secondary soliton generated from soliton splitting. See more details in Supplementary note 5.

Combining the advantages of μJ-level pulse energy, octave-wide spectral coverage and good spatial and spectral coherence, the ultra-broadband DW demonstrated here represents a major step forward to high-quality, single-cycle or even sub-cycle UV pulse generation, which is critical for many applications in ultrafast electron microscopy58, femtosecond spectroscopy59, advanced photolithography60,61 and UV frequency comb62,63. The results also indicate that the introduction of two or even more driving pulses in the nonlinear optical system may present some new opportunities for observing unique dynamics and phenomena concerning nonlinearly-coupled propagation of multiple pulses56,64,65, offering additional degrees of freedom for manipulating nonlinear optics experiments.

Methods

Experimental set-up

The broadband UV DW generation system consists of two stages, including HCF compression and broadband DW emission, driven by a commercial Ti: sapphire femtosecond laser, delivering 800 nm, 50 fs pulses at a repetition rate of 1 kHz. In the first stage, the pump pulses with an energy of 600 μJ were compressed using an HCF compression set-up, consisting of a 78-cm-long capillary fibre, with 250 μm inner diameter, filled with Ar gas, followed by a broadband attenuator and two pairs of chirped mirrors (103367, Layertec). The system can compress the input pulses from 50 fs to 18 fs (10 fs) at 130 mbar (330 mbar) Ar-gas pressure. The central wavelengths of the compressed pulses were measured to be around 766 nm and 781 nm for 10 fs and 18 fs pulses, respectively (see Supplementary note 6 for more details). The transmission efficiency of this system is ~40%, corresponding to a maximum output pulse energy of 240 μJ. In the second stage, another 42-cm-long Ne-filled capillary fibre with a core diameter of 100 μm was used to enable the broadband UV DW generation. See the Supplementary Fig. S1 for more details of the set-up.

Pulse spectrum and energy measurements

Measure the pulse spectrum in the wavelength range of 180 nm to 300 nm using a UV spectrometer (Maya2000-Pro, 155-310 nm, Ocean Insights), in the wavelength range of 200 nm to 400 nm using another UV spectrometer (Maya2000-Pro, 200–400 nm, Ocean Optics), in the wavelength range of 400 nm–1000 nm using a spectrometer from UV to near-infrared region (Maya2000-Pro, 210-1100 nm, Ocean Optics). The last two spectrometers have been calibrated and can be used to measure the pulse spectrum within a wide spectral range from 200 nm to 1000 nm. By interpolating data within the overlapping area and combining the spectra measured by these two spectrometers, we finally obtained the full optical spectra at the HCF output port, as shown in Fig. 1b, c and Fig. 3a. It should be noted that in the spectral measurements, the laser pulse at the HCF output port was divided into two parts by a fused silica wedge. The transmitted pulse entered the integrating sphere connected to the fibre-coupled UV spectrometer (Maya2000-Pro, 200–400 nm, Ocean Optics), while the reflected pulse entered another integrating sphere connected to the fibre-coupled spectrometer (Maya2000-Pro, 210–1100 nm, Ocean Optics). Moreover, the broadband UV DW spectrum with a spectral range from 180 nm to 300 nm generated at Ne-gas pressure of 3 bar, as shown in Fig. 6, was measured using the UV spectrometer (Maya2000-Pro, 155-310 nm, Ocean Insights) placed in the N2-filled chamber connected to the HCF output port.

The pulse energy at the input and output ends of the first and second stage HCF was measured using a thermal power meter (3A-P, Ophir). The energy measurements of the broadband UV DW pulses were achieved through the use of bandpass filters (Pelham Research Optical for 200−260 nm with 20 nm interval; FBH343-10, Thorlabs for 343 nm; FGUV11, Thorlabs for 275-375 nm), a photodiode (PD300-UV, Ophir), and a UV spectrometer (Maya2000-Pro, 200–400 nm, Ocean Optics). We performed the energy measurement of the broadband UV DW pulse generated at the input pulse energy of 64 μJ and Ne-gas pressure of 5 bar as an example. In the measurements, the bandpass filter was firstly used to filter out a portion of the spectrum of the broadband UV DW pulse, and the photodiode and UV spectrometer were used to measure the energy and spectral intensity of the filtered UV pulse. These results were used to calibrate the measured spectral energy density. Then the UV spectrometer was used to measure the spectral intensity of the broadband UV DW pulse before the bandpass filter. Finally, based on the calibrated spectral energy density and the spectral intensity before filtering, the energy of the broadband UV DW pulse can be estimated to 4.07 μJ, see Fig. 3c. Using the same method, the energy of the UV DW pulses with different bandwidths and central wavelengths have also been measured, and the results are illustrated in Figs. 3c, 6.

Beam profile measurements

In Fig. 1d, near-field beam profiles of the broadband DW pulse were measured at different wavelengths, using several optical filters (Pelham Research Optical for 200−260 nm; FBH343-10, Thorlabs for 343 nm; FGUV11, Thorlabs for 275-375 nm) and a CCD camera (BGS-USB3-SP932U, Ophir-Spiricon).

Numerical simulations

The numerical simulations (see Figs. 1–4) were performed using both the GNLSE model and the single-mode UPPE model36,37,38,39 (including photoionization term). The single-mode UPPE model can be expressed as

where \(\tilde{E}(z,\omega )\) is the electric filed in frequency domain, \(\beta (\omega )\) the propagation constant, \({v}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\) the group velocity, \(\alpha (\omega )\) the linear loss of the fibre, c the light speed in vacuum, \({\varepsilon }_{0}\) the vacuum permittivity, and \({\tilde{P}}_{NL}(z,\omega )\) the nonlinear response in the frequency domain. Using the complex amplitude of the light field, the electric field can be expressed in the time domain as \(E(z,t)=[A(z,t){e}^{-i{\omega }_{0}t}+c.c.]/2\), t is the time, and c.c. represents the complex conjugation. In the simulations, we used the measured pulses as input (see Supplementary note 6) and considered the dispersion introduced by a 0.5 mm-thick fused silica window. The propagation constant of the gas-filled HCF can be expressed as41

where \({n}_{gas}\) is the refractive index of the filling gas, which is related to light frequency, gas pressure and temperature, a is core radius of the HCF, and \({u}_{nm}\) is the mth zero of Bessel function \({J}_{n-1}\), where \(m=n=1\) corresponds to the fundamental mode of the HCF. The linear loss of the HCF can be given as41

where \(\eta\) is the ratio of the refractive index of the cladding medium to that of the filling gas.

In Eq. (2), the nonlinear response \({\tilde{P}}_{NL}(z,\omega )\) includes the Kerr effect and ionization-induced plasma polarization, and the corresponding expressions and descriptions are shown in Supplementary note 2. The solution method for Eq. (2) is to use the symmetric split-step Fourier method, where the nonlinear term is calculated using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta algorithm. It should be noted that the numerical results simulated by the UPPE model show excellent agreements with those simulated by the GNLSE model. See Supplementary note 2 for more details.

Calculation of the complex degree of first-order coherence

In Fig. 4a, 50 numerical simulations with different quantum noise (the simulation parameter are the same as those in Fig. 1c), performed using the UPPE model, can be used to calculate the complex degree of first-order coherence of the broadband UV DW, which can be given as49

where \({\tilde{E}}_{m}(\omega )\) and \({\tilde{E}}_{n}(\omega )\) are two different electric fields in the frequency domain and \({\tilde{E}}_{m}^{*}(\omega )\) is the complex conjugate of electric field \({\tilde{E}}_{m}(\omega )\). The angle brackets denote ensemble averaging over the independent simulation results.

Estimation of the relatively intensity noise

The RMS value of the RIN of the broadband UV DW pulse train over short and long time scales is calculated using

where \({X}_{n}\) is the intensity of the nth broadband UV DW pulse, \(\bar{X}\) is the average value of the M measured pulses. The RIN value of the broadband UV DW pulse can be estimated through \({\delta }_{RMS}/\bar{X}\). Within a short time scale of 100 ms, a pulse train consisting of 100 broadband UV DW pulses was recorded, and the intensity of each pulse was characterized by a photodetector and an oscilloscope. Thus \({X}_{n}\) is equal to the peak voltage of the nth electrical signal, and M = 100. While within a long time scale of 30 minutes, the broadband UV DW spectrum was measured for 1000 times with a time interval of 1.8 s and scanning time of 0.1 s, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. Therefore, \({X}_{n}\) is equal to the spectral area (equivalent to pulse energy) of the nth broadband UV DW pulse, and M = 1000. See Supplementary note 7 for more details.

Estimation of the timing jitter

Since the phase noise is quite low at low-order harmonics, we measured the single-sideband (SSB) phase noise spectrum of the 80th harmonics (at 80 kHz) for the broadband UV DW pulse (see Supplementary note 7 for more details). The relative pulse timing jitter could be estimated using the expression66

where \({T}_{0}\) is the time between pulses, and \({P}_{noise}\) is the SSB noise power integrated over the selected frequency range.

Pulse characterization measurements

Temporal characterization of 10 fs and 18 fs pump pulses output from the HCF compression stage was based on a home-built second-harmonic generation (SHG) FROG set-up with all reflective optics. In this set-up, the sum-frequency signal was generated in a 10 μm-thick beta barium borate (BBO) crystal cut for type I phase-matching. Pulse characterization measurement of broadband UV DW pulse at 250 nm was carried out using a home-built SD-FROG set-up. While the optical layout of the SD-FROG is similar to that of the SHG-FROG, a 50 μm-thick fused silica was used as the nonlinear medium and several aluminum mirrors were used to provide high reflections for the UV pulses. The SD-FROG set-up was placed in a gas chamber filled with air-helium mixture. Two chirp mirrors were used in the chamber to compensate the pulse chirp accumulated over the optical path. In addition, the GDD value in the optical path was precisely adjusted by varying the ratio of helium gas in the mixture, thereby minimizing the residual pulse chirp and therefore shortening UV DW pulse width at the measurement point, see Supplementary note 1 for more details of the diagnosis set-up. The results of ultrafast pulse characterizations using the SHG-FROG and SD-FROG set-ups are illustrated in Supplementary note 6.

Data availability

The experimental and numerical data generated in this study have been deposited in the Science Data Bank [https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.12337].

Code availability

The code used in this paper to process these data can be accessed in an open data-storage platform [https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.12337].

References

Shabat, A. & Zakharov, V. Exact theory of two-dimensional self-focusing and one-dimensional self-modulation of waves in nonlinear media. Sov. Phys. JETP 34, 62 (1972).

Hasegawa, A. & Tappert, F. Transmission of stationary nonlinear optical pulses in dispersive dielectric fibers. I. Anomalous dispersion. Appl. Phys. Lett. 23, 142–144 (1973).

Mollenauer, L. F. & Gordon, J. P. Solitons in Optical Fibers: Fundamentals and Applications (Academic Press, 2006).

Balciunas, T. et al. A strong-field driver in the single-cycle regime based on self-compression in a kagome fibre. Nat. Commun. 6, 6117 (2015).

Travers, J. C., Grigorova, T. F., Brahms, C. & Belli, F. High-energy pulse self-compression and ultraviolet generation through soliton dynamics in hollow capillary fibres. Nat. Photon. 13, 547–554 (2019).

Russell, P. S. J., Hölzer, P., Chang, W., Abdolvand, A. & Travers, J. C. Hollow-core photonic crystal fibres for gas-based nonlinear optics. Nat. Photon. 8, 278–286 (2014).

Skryabin, D. V., Luan, F., Knight, J. C. & Russell, P. S. J. Soliton self-frequency shift cancellation in photonic crystal fibers. Science 301, 1705–1708 (2003).

Huang, Z.-Y. et al. Continuously wavelength-tunable blueshifting soliton generated in gas-filled photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Lett. 44, 1805–1808 (2019).

Joly, N. Y. et al. Bright spatially coherent wavelength-tunable deep-UV laser source using an Ar-filled photonic crystal fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 203901 (2011).

Brahms, C., Belli, F. & Travers, J. C. Infrared attosecond field transients and UV to IR few-femtosecond pulses generated by high-energy soliton self-compression. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043037 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Measurements of microjoule-level, few-femtosecond ultraviolet dispersive-wave pulses generated in gas-filled hollow capillary fibers. Opt. Lett. 47, 4830–4833 (2022).

Belli, F., Abdolvand, A., Chang, W., Travers, J. C. & Russell, P. S. J. Vacuum-ultraviolet to infrared supercontinuum in hydrogen-filled photonic crystal fiber. Optica 2, 292–300 (2015).

Ermolov, A., Mak, K. F., Frosz, M. H., Travers, J. C. & Russell, P. S. J. Supercontinuum generation in the vacuum ultraviolet through dispersive-wave and soliton-plasma interaction in noble-gas-filled hollow-core photonic crystal fiber. Phys. Rev. A 92, 033821 (2015).

Jiang, X. et al. Deep-ultraviolet to mid-infrared supercontinuum generated in solid-core ZBLAN photonic crystal fibre. Nat. Photon. 9, 133–139 (2015).

Guo, H.-R. et al. Mid-infrared frequency comb via coherent dispersive wave generation in silicon nitride nanophotonic waveguides. Nat. Photon. 12, 330–335 (2018).

Sollapur, R. et al. Resonance-enhanced multi-octave supercontinuum generation in antiresonant hollow-core fibers. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e17124 (2017).

Elu, U. et al. Seven-octave high-brightness and carrier-envelope-phase-stable light source. Nat. Photon. 15, 277–280 (2021).

Wai, P. K. A. et al. Nonlinear pulse propagation in the neighborhood of the zero-dispersion wavelength of monomode optical fibers. Opt. Lett. 11, 464–466 (1986).

Kodama, Y. & Hasegawa, A. Nonlinear pulse propagation in a monomode dielectric guide. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 23, 510–524 (1987).

Akhmediev, N. & Karlsson, M. Cherenkov radiation emitted by solitons in optical fibers. Phys. Rev. A 51, 2602–2607 (1995).

Erkintalo, M., Xu, Y.-Q., Murdoch, S. G., Dudley, J. M. & Genty, G. Cascaded phase matching and nonlinear symmetry breaking in fiber frequency combs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 223904 (2012).

Brasch, V. et al. Photonic chip-based optical frequency comb using soliton Cherenkov radiation. Science 351, 357–360 (2016).

Telle, H. R. et al. Carrier-envelope offset phase control: A novel concept for absolute optical frequency measurement and ultrashort pulse generation. Appl. Phys. B 69, 327–332 (1999).

Del’Haye, P. et al. Phase-coherent microwave-to-optical link with a self-referenced microcomb. Nat. Photon. 10, 516–520 (2016).

Wright, L. G., Christodoulides, D. N. & Wise, F. W. Controllable spatiotemporal nonlinear effects in multimode fibres. Nat. Photon. 9, 306–310 (2015).

Wright, L. G., Wabnitz, S., Christodoulides, D. N. & Wise, F. W. Ultrabroadband dispersive radiation by spatiotemporal oscillation of multimode waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 223902 (2015).

Köttig, F. et al. Mid-infrared dispersive wave generation in gas-filled photonic crystal fibre by transient ionization-driven changes in dispersion. Nat. Commun. 8, 813 (2017).

Köttig, F., Tani, F., Biersach, C. M., Travers, J. C. & Russell, P. S. J. Generation of microjoule pulses in the deep ultraviolet at megahertz repetition rates. Optica 4, 1272–1276 (2017).

Chen, Y.-F. et al. Photoionization-assisted, high-efficiency emission of a dispersive wave in gas-filled hollow-core photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Express 28, 17076–17085 (2020).

Lüpken, N. M. et al. Numerical and experimental demonstration of intermodal dispersive wave generation. Laser Photon. Rev. 15, 2100125 (2021).

Oh, D. Y. et al. Coherent ultra-violet to near-infrared generation in silica ridge waveguides. Nat. Commun. 8, 13922 (2017).

Genty, G., Lehtonen, M. & Ludvigsen, H. Effect of cross-phase modulation on supercontinuum generated in microstructured fibers with sub-30 fs pulses. Opt. Express 12, 4614–4624 (2004).

Gorbach, A. V. & Skryabin, D. V. Light trapping in gravity-like potentials and expansion of supercontinuum spectra in photonic-crystal fibres. Nat. Photon. 1, 653–657 (2007).

Travers, J. C. et al. Phase-matching and gain of deep-UV dispersive-wave generation. In CLEO: 2011 CJ3_1 (OSA, 2011).

Travers, J. C., Chang, W., Nold, J., Joly, N. Y. & Russell, P. S. J. Ultrafast nonlinear optics in gas-filled hollow-core photonic crystal fibers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 28, A11–A26 (2011).

Agrawal, G. P. Nonlinear Fiber Optics (Academic Press, 2007).

Kinsler, P. Optical pulse propagation with minimal approximations. Phys. Rev. A 81, 013819 (2010).

Chang, W. et al. Influence of ionization on ultrafast gas-based nonlinear fiber optics. Opt. Express 19, 21018–21027 (2011).

Huang, Z.-Y. et al. Highly-tunable, visible ultrashort pulses generation by soliton-plasma interactions in gas-filled single-ring photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Express 27, 30798–30809 (2019).

Brabec, T. & Krausz, F. Nonlinear optical pulse propagation in the single-cycle regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 3282–3285 (1997).

Marcatili, E. A. J. & Schmeltzer, R. A. Hollow metallic and dielectric waveguides for long distance optical transmission and lasers. The Bell System Tech. J. 43, 1783–1809 (1964).

Börzsönyi, A., Heiner, Z., Kalashnikov, M. P., Kovács, A. P. & Osvay, K. Dispersion measurement of inert gases and gas mixtures at 800 nm. Appl. Opt. 47, 4856–4863 (2008).

Dudley, J., Genty, G. & Coen, S. Supercontinuum generation in photonic crystal fiber. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 1135 (2006).

Golovchenko, E. A., Dianov, E. M., Prokhorov, A. M. & Serkin, V. N. Decay of optical solitons. Soviet J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 42, 87 (1985).

Ohkuma, K., Ichikawa, Y. H. & Abe, Y. Soliton propagation along optical fibers. Opt. Lett. 12, 516–518 (1987).

Agrawal, G. P., Baldeck, P. L. & Alfano, R. R. Temporal and spectral effects of cross-phase modulation on copropagating ultrashort pulses in optical fibers. Phys. Rev. A 40, 5063–5072 (1989).

Alfano, R. R. The supercontinuum laser source: fundamentals with updated references (Academic Press, 2006).

Biancalana, F., Skryabin, D. V. & Yulin, A. V. Theory of the soliton self-frequency shift compensation by the resonant radiation in photonic crystal fibers. Phys. Rev. E 70, 016615 (2004).

Dudley, J. M. & Coen, S. Coherence properties of supercontinuum spectra generated in photonic crystal and tapered optical fibers. Opt. Lett. 27, 1180–1182 (2002).

Genty, G., Surakka, M., Turunen, J. & Friberg, A. T. Complete characterization of supercontinuum coherence. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 28, 2301–2309 (2011).

Skryabin, D. V. & Gorbach, A. V. Colloquium: Looking at a soliton through the prism of optical supercontinuum. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1287–1299 (2010).

Yulin, A. V., Skryabin, D. V. & Russell, P. S. J. Four-wave mixing of linear waves and solitons in fibers with higher-order dispersion. Opt. Lett. 29, 2411–2413 (2004).

Efimov, A. et al. Interaction of an Optical Soliton with a Dispersive Wave. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 213902 (2005).

Skryabin, D. V. & Yulin, A. V. Theory of generation of new frequencies by mixing of solitons and dispersive waves in optical fibers. Phys. Rev. E 72, 016619 (2005).

Philbin, T. G. et al. Fiber-Optical Analog of the Event Horizon. Science 319, 1367–1370 (2008).

Demircan, A., Amiranashvili, S. & Steinmeyer, G. Controlling Light by Light with an Optical Event Horizon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 163901 (2011).

Webb, K. et al. Nonlinear optics of fibre event horizons. Nat. Commun. 5, 4969 (2014).

Hassan, M. T., Baskin, J. S., Liao, B. & Zewail, A. H. High-temporal-resolution electron microscopy for imaging ultrafast electron dynamics. Nat. Photon. 11, 425–430 (2017).

Kotsina, N., Brahms, C., Jackson, S. L., Travers, J. C. & Townsend, D. Spectroscopic application of few-femtosecond deep-ultraviolet laser pulses from resonant dispersive wave emission in a hollow capillary fibre. Chem. Sci. 13, 9586–9594 (2022).

Madsen, M. H. & Hansen, P. E. Scatterometry—fast and robust measurements of nano-textured surfaces. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 4, 023003 (2016).

Wurm, M. et al. Metrology of nanoscale grating structures by UV scatterometry. Opt. Express 25, 2460–2468 (2017).

Cundiff, S. T. & Ye, J. Colloquium: Femtosecond optical frequency combs. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 325–342 (2003).

Grinin, A. et al. Two-photon frequency comb spectroscopy of atomic hydrogen. Science 370, 1061–1066 (2020).

Demircan, A., Amiranashvili, S., Brée, C. & Steinmeyer, G. Compressible Octave Spanning Supercontinuum Generation by Two-Pulse Collisions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 233901 (2013).

Jiang, Y.-J. et al. Ultraviolet pulse compression via cross-phase modulation in a hollow-core fiber. Optica 11, 291–296 (2024).

von der Linde, D. Characterization of the noise in continuously operating mode-locked lasers. Appl. Phys. B 39, 201–217 (1986).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62205353 to Z.Y.H., No. 62275254 to M.P., No. 61925507 to Y.X.L, No. 12388102 to R.X.L.), the National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (No. BX2021328 to Z.Y.H.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M703325 to Z.Y.H.), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Science (No. XDB0650000 to M.P.), the Shanghai Science and Technology Plan Project Funding (No. 23JC1410100 to M.P.), the Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan (No. 21ZR1482700 to M.P.), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFA1604401 to Y.X.L.), Shanghai Science and Technology Committee Program (Nos. 22DZ1100300, 22560780100 and 23560750200 to Y.X.L.), Fuyang High-level Talent Group Project (W.B.H., M.P. and X.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y.H., M.P., and Y.X.L. conceived the work. T.D.C., Y.Y., Z.Y.H., D.H.L., and X.S.C carried out the experiments. Z.Z.L, W.B.H., X.J., Y.X.L., and R.X.L. provided necessary experimental equipment and resources. T.D.C., J.Y.P., and Z.Y.H. performed the numerical simulations. T.D.C., Z.Y.H., and M.P. made the theoretical and experimental analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alexey Yulin, Huanfa Peng and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, T., Pan, J., Huang, Z. et al. Octave-wide broadening of ultraviolet dispersive wave driven by soliton-splitting dynamics. Nat Commun 15, 8671 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52955-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52955-6

This article is cited by

-

Intelligent single-shot full-field characterization over femtosecond pulses

Nature Communications (2025)