Abstract

We present SpliceTransformer (SpTransformer), a deep-learning framework that predicts tissue-specific RNA splicing alterations linked to human diseases based on genomic sequence. SpTransformer outperforms all previous methods on splicing prediction. Application to approximately 1.3 million genetic variants in the ClinVar database reveals that splicing alterations account for 60% of intronic and synonymous pathogenic mutations, and occur at different frequencies across tissue types. Importantly, tissue-specific splicing alterations match their clinical manifestations independent of gene expression variation. We validate the enrichment in three brain disease datasets involving over 164,000 individuals. Additionally, we identify single nucleotide variations that cause brain-specific splicing alterations, and find disease-associated genes harboring these single nucleotide variations with distinct expression patterns involved in diverse biological processes. Finally, SpTransformer analysis of whole exon sequencing data from blood samples of patients with diabetic nephropathy predicts kidney-specific RNA splicing alterations with 83% accuracy, demonstrating the potential to infer disease-causing tissue-specific splicing events. SpTransformer provides a powerful tool to guide biological and clinical interpretations of human diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

RNA splicing features an intricate regulatory program that contributes to the phenotypic diversities of cells. More than 90% of human genes undergo alternative splicing, a key regulator of gene expression that generates diverse transcripts from a single protein-coding gene1. A splice site, a specific sequence motif located at the junction of an exon and an intron on pre-mRNA, plays a crucial role in alternative splicing. It is recognized by the spliceosome, a large RNA–protein complex that catalyzes the removal of introns, thereby guiding the splicing process2. Mutations could affect RNA splicing by altering splice sites, and proximal or distal cis-regulatory elements (CREs), which in turn change protein sequence and function, and result in human diseases3. For instance, Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome, a rare and fatal childhood disorder characterized by accelerated aging, is caused by the activation of a cryptic splice site in the LMNA gene4. Therefore, recognizing variations in alternative splicing becomes an essential task for clinical diagnosis.

To overcome this challenge, computational algorithms have been developed to decipher the sequence-based splicing code and to predict the splicing effects of disease-associated genetic variations. Over the past two decades, statistical methods such as MaxEntScan5, and HAL6 have been developed to identify splice sites by considering closely neighboring k-mers. Subsequently, deep learning algorithms like MMSplice7 emerged to predict splicing effects by incorporating longer sequence contexts through the utilization of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). More recently, SpliceAI8, a state-of-the-art deep learning algorithm, has demonstrated significant improvements in splicing prediction compared to earlier algorithms. By leveraging complex CNN architectures, SpliceAI is capable of processing sequences of up to 10,000 base pairs. Furthermore, Pangolin9 trained a series of models similar to SpliceAI to predict splice effects in four tissues: brain, heart, liver, and testis. In addition, other algorithms have been developed to address similar tasks in splicing prediction. For instance, CADD-Splice10 takes outputs of multiple tools, including MMSplice and SpliceAI, as features to predict the splicing effects of genetic variants. AbSplice11 requires the use of SpliceAI along with additional input from RNA-seq data to predict the splicing effects of genetic variations. SpliceBERT12, on the other hand, employs a Transformer-based model, BERT, to handle splicing-related tasks across multiple species. In practical applications, these existing algorithms have proven to be effective tools in aiding researchers in the study of disease-related gene mutations13,14. However, it is important to note that these algorithms have certain limitations in terms of accuracy and functionality when applied in real-world scenarios15.

A major limitation of previous methods lies in the ignorance of the tissue specificity of splicing and its clinical significance. Alternative splicing varies across cell types and tissues16. The brain, for example, is known to exhibit complex patterns of splicing. Variations in brain-specific alternative splicing are significantly associated with neurological disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), schizophrenia (SCZ), and bipolar disorder (BD)17,18.

For instance, aberrant splicing in CPEB4 has been reported to be highly associated with autism-like phenotype19. However, these alternative splicing events may not be detectable in clinically accessible tissues such as blood. Therefore, accurate prediction of splice-altering mutations in a tissue-specific manner holds significant clinical importance for genetic diagnosis. Unfortunately, most existing algorithms did not address the tissue-specificity of splicing into their model, which limits their practical application.

We present SpliceTransformer (SpTransformer), a transformer-based deep learning framework that predicts tissue-specific RNA splicing events directly from the mRNA sequence context. The success of large models in natural language processing (NLP) has proved the power of Transformer models, a deep learning architecture with multi-head attention layers. Vanilla Transformer architecture has splendid capabilities to consider sequence contexts, but requires unacceptable time and power when input comes longer. We employed attention layers specifically designed for handling long-range inputs, in order to echo the significance of considering long sequence contexts in analyzing splicing events8,12,20. We demonstrated the superior performance of SpTransformer compared to other deep learning models, and applied SpTransformer to accurately predict splicing effects in different tissues for various disease manifestations. Tissue-specific splicing alterations predicted by SpTransformer can be a powerful tool to guide clinical diagnosis and advance our understanding of human diseases, particularly for the less clinically accessible tissues. SpTransformer is available as an online server at http://tools.shenlab-genomics.org/tools/SpTransformer.

Results

Tissue-specific prediction of splicing using attention-based deep learning

SpTransformer is a computational model that predicts the probability of each position in a pre-mRNA input sequence being a splice donor, splice acceptor, or neither in all and 15 different tissues simultaneously (Fig. 1a). Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of deep convolutional networks in capturing splicing patterns for general sites or specific tissues7,8,21. However, the multitask modeling of tissue-specific splicing poses additional challenges and has been rarely attempted. Here, we introduced the transformer architecture with multi-head attention layers to better understand the contextual features in both short- and long-range sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, we expanded the deep learning model’s background knowledge by introducing two encoders with convolution structure, and a specialized training strategy that enabled the encoders to learn from two datasets with different organizations but similar biological significance. This training strategy aimed to enable the encoders to estimate biological sequences from different hidden feature spaces, akin to a visual model that examines a human face from different perspectives. To train SpTransformer, we compiled splicing data from different sources including human adult tissue data from the GTEx database22, and an independent mammalian organ transcriptome dataset of four species including human, rhesus macaque, mouse, and rat23. We split the data by selecting subsets of chromosomes as training, and the remaining chromosomes with paralogs excluded as the testing set (see “Methods”). The relationship between the tissue classes and their corresponding detailed tissue types is presented (Supplementary Data 1).

a The SpTransformer model takes an only sequence as input and predicts tissue-specific splicing in 15 human tissues. The model can be used to evaluate genetic variants and predict tissue-specific splicing alterations. b Performance of 6 algorithms in splice site prediction task. Top-k accuracy is calculated by choosing a threshold to make predicted positive sites and actual splice sites have the same number, then computing the fraction of correctly predicted splice sites. PR-AUC is the area under the precision-recall curve. c Tissue-usage prediction of SpTransformer in comparison with other models. d The distribution of SpTransformer prediction score for tissue usages of splice sites in the test dataset. Tissue usages were grouped into low (<0.5) and high (≥0.5) by their original usage ratio across all samples in the same tissue types. a Created with BioRender.com, was released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license.

We evaluated the performance of SpTransformer on predicting all tissue splice sites in the held-out test set, and compared it against several popular methods: SpliceAI8, Pangolin9, MMSplice7, HAL6, and MaxEntScan5. SpTransformer achieved the highest performance in terms of both Top-k accuracy and AU-PRC, with approximately 85% top-k accuracy and 91% AU-PRC (Fig. 1b). Most importantly, we evaluated SpTransformer prediction on different tissues in relation to the usage of splice sites across 15 human tissues. SpTransformer demonstrated a clear advantage over other tools for distinguishing splicing sites with low vs high tissue usage (Fig. 1c, “Methods”). Specifically, the distribution of tissue-specific splicing probabilities predicted by SpTransformer aligns well with the actual usage of splice sites in each of the 15 tissues as measured by RNA-seq in the GTEx database (Fig. 1d).

One of the enhancements of SpTransformer over previous methods is the usage of additional RNA-seq data, not only from humans but also from three other mammalian species. The similarity and homology of splicing across different mammalians have been reported in previous research23. Thus, we expect splicing data from diverse genomes could enhance the model’s ability to understand the tissue-specific sequence features of splicing. To investigate the real impact of including these datasets, we further conducted an ablation study using different training sets (“Methods”). SpTransformer trained with all four extra mammalian species datasets demonstrated a clear advantage over the versions trained with partial or no extra datasets (Supplementary Table 1). This advantage was consistently shown in the prediction of the usage of splice sites across all 15 human tissues (Supplementary Fig. 2). These observations underscore that the inclusion of an extra mammalian dataset enhances both the identification of splice sites and the tissue-specificity prediction. A thorough analysis of the extra mammalian datasets revealed that the primate dataset was the primary contributor to the model. We further refined the SpliceAI source code to two versions: one named SpliceAI-retrained was re-train with the same training datasets as SpTransformer, and the other one named SpliceAI-modified was modified only the output to be able to predict tissue-specificity without any change in training. We also applied other popular splicing prediction tools including MMSplice, HAL, and MaxEntScan. SpTransformer consistently outperformed them (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the superior performance is attributable not only to the training set but also to the transformer structure. Additionally, we observed that the model’s accuracy improved when it processed longer input sequences, which agreed with our expectations (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Regulatory code of tissue-specific splicing learned by Sp transformer

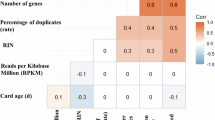

Next, we sought to understand the regulatory contexts learned by SpTransformer that contribute to the tissue-specific usage of splicing sites. As expected, splicing site tissue usage correlates with gene expression level (Fig. 2a). This suggests that the tissue-specific splicing is, at least in part, achieved through expressional regulation, and SpTransformer implicitly learned this information by modeling tissue-specific splicing.

a Corresponding gene expression of tested splice sites in the test dataset, grouped by tissue usage of splice sites. The two-sided Fisher’s test revealed a significant association between tissue usage and gene expression of splice sites (“Low” vs “Moderate”/“High”. “Low”: 0–1 NAUC, “Moderate”: 1–20 NAUC, ''High'': over 20 NAUC. The NAUC is an estimation of a gene’s expression level, annotated by the ASCOT66 database.). Tissue usage was not totally dominated by gene expression. b Impact of in silico mutation around intron in the GLA gene. SpTransformer considers sequence features both proximal and distal to the splice donor site. Mutagenesis weight was calculated by the decrease in the predicted strength of the splice site when that nucleotide is mutated. c Impact of in silico mutation around exons in the APBB2 gene. Several known RBP motifs were found in regions of large weight. d De novo motifs that influence the tissue-usage prediction of SpTransformer (left) and their presentations in different tissues (right). The names of similar RBP motifs, as reported by MEME tools, are marked.

It was generally accepted that the sequence context determinants, i.e., CREs, act as platforms for the recruitment of both tissue type-restricted and broadly expressed transcripts24,25. Thus, we attempted to understand the cis-regulatory sequence context learned by SpTransformer for its tissue-specific prediction performance through in silico mutagenesis. Results suggest that SpTransformer captures sequence features that are both proximal and distal to the splice site. In Fig. 2b, we illustrate the sequence feature identified by SpTransformer using the GLA gene as an example. The GLA gene, which encodes the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A, is closely associated with Fabry disease, a rare lysosomal storage disorder. SpTransformer detected the “GT” sequence around the exon–intron junction, identifying it as a splice donor site. Additionally, SpTransformer recognized regions with relatively high mutagenesis weight at 300 nt, 400 nt, and 900 nt downstream from GLA exon 4, demonstrating its capability to detect sequence features in distal intronic regions.

Moreover, SpTransformer identified putative splicing elements that matched motifs of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) with splicing regulatory functions reported in the corresponding tissue. For instance, the binding motif of PTBP1, a protein that plays important roles in alternative splicing in neuronal development regulation26, was detected in APBB2. Alternative splicing in APBB2 results in multiple transcript variants, and polymorphisms in this gene have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease27 (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 4). To understand the sequence motifs learned by SpTransformer, we further applied motif discovery analysis with the help of the MEME toolbox28, and identified multiple de novo sequence motifs that influenced the model’s prediction (Fig. 2d). Consistent with previous reports, we observed that sequences containing the consensus splicing motif AG-GT (Fig. 2d, 1, 2) had a substantial impact on the SpTransformer model’s prediction of splicing events. This motif is the most frequently recognized sequence pattern by the spliceosomes, and could be detected in all 15 tissues by SpTransformer. Additionally, we discovered some highly specific motifs that were only present in one or two tissues (Fig. 2d, 3–14). For example, Fig. 2d-7 matched with the motifs of RBP DDX19B, ELAVL4, and FMR1, while Fig. 2d-9 matched with SRSF4, according to the ATtRACT29 database. There were also de novo motifs that were not similar to known RBP motifs.

In summary, by learning the tissue-specific splicing events, SpTransformer was able to implicitly learn the joint contribution of expression and sequence context to the tissue-specific regulatory code.

Genome-wide analysis of splicing dysregulation and human diseases

To quantify the splicing alterations of human genetic variations predicted by SpTransformer, we calculated the ΔSplice score for each genetic variation and presented a graphical visualization (Fig. 3a, “Methods”). To assess the impact of various genetic variations for splicing, we applied SpTransformer to assess the ΔSplice scores of all tissue for 1,273,053 single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the ClinVar database30. For instance, SpTransformer identified a cryptic splicing site with ΔSplice of 0.99, which was created 24 nt upstream of the genetic mutation chr4:154569800G > T in the Fetal hemoglobin gene FGB. This mutation is known to cause Congenital Afibrinogenemia, a rare bleeding disorder featured by impairment of the blood clotting process (Fig. 3b). Moreover, in the case of the TP53 gene mutation chr17:7675994C > A, which causes Li-Fraumeni Syndrome and predispose people to various types of cancer, SpTransformer successfully identified a cryptic splice site generated 200 nt upstream of the mutation. The splicing alterations in both cases have been experimentally validated31,32, demonstrating the accuracy of SpTransformer in predicting these distinctly different splicing alterations.

a SpTransformer is applied to evaluate the splicing effect of a single nucleotide variant by calculating an ΔSplice score and matching graphical representations. b Examples of two pathogenic mutations in the ClinVar database. SpTransformer successfully predicted splicing changes even far from variants (right panel). Both cases were validated by RT-PCR in previous studies c The distribution of mutations classified by clinical significance within several intervals of ΔSplice scores. As the ΔSplice score increases, the ratio of pathogenic mutations becomes larger. d Distributions of ΔSplice scores of all SNVs, grouped by both pathogenicity in ClinVar database and annotated variant type. The number of SNVs and the proportion of SNVs above/below the cutoff were annotated. The bar chart on the left aggregates the data by rows, while the bar chart at the top tabulates the data by columns. SNVs with alternative pathogenicity annotations (e.g., “conflicting interpretations”) were excluded from the analysis. a Created with BioRender.com, was released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license.

We then applied SpTransformer to make massive splicing alteration predictions on the ClinVar annotated SNVs, and assessed the performance of SpTransformer, Pangolin, and SpliceAI on distinguishing pathogenic vs benign variants. Again, SpTransformer demonstrated the best performance with AU-PRC of 0.98 (Supplementary Fig. 5). To gain further insights into the relationship between splicing-altering variants and pathogenic mutations, we analyzed the SpTransformer predicted ΔSplice score for all ClinVar SNVs with different pathogenic labels. As expected, the proportion of pathogenic and likely pathogenic SNVs increased with higher ΔSplice scores (Fig. 3c). Specifically, as shown in Fig. 3d, the Splice acceptor/donor sites had the most ΔSplice scores close to 1, while missense and nonsense SNVs showed minimal ΔSplice scores. Interestingly, we observed a bimodal distribution of ΔSplice scores for intronic and synonymous SNVs in the pathogenic and likely pathogenic groups, with 57–64% of intronic (likely) pathogenic variants, and 56–58% of (likely) pathogenic synonymous variants predicted as splice altering mutations by SpTransformer. We also performed the same analysis with the retrained SpliceAI model, which showed consistency with the previous result (“Methods”, Supplementary Fig. 6). Identifying pathogenic variants and interpreting variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in noncoding regions and synonymous mutations has been a long-standing challenge in the field. Our analysis unveils a significant contribution of splicing alterations in intronic and synonymous pathogenic mutations, underscoring the value of applying SpTransformer in regions beyond splicing sites for diagnosis and interpretation of candidate pathogenic mutations or VUS.

Tissue-specific splicing alterations associated with disease manifestation

A variant could impact splicing universally or only in certain specific tissues. Initially, we modified ΔSplice as ΔTissueusage scores to quantify splice alterations in each tissue. However, a drawback arose that mutations consistently affecting splicing in all tissues might receive relatively higher scores than those highly tissue-specific, making cross-tissue comparisons challenging. To address this, we derived a z-score based on the empirical distribution of selected GTEx data (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7, “Methods”).

a The strategy to derive tissue specificity variants from model prediction. We created a reference set of common splicing sites to derive background distribution and calculate tissue-specific z-scores for new variants in order to make fair comparisons across tissues, and gene enrichment is calculated based on tissue-specific splice-altering SNVs. b Top five genes enriched for tissue-specific splice-altering SNVs for each of the 15 tissues as predicted by SpTransformer. The size of the bubbles represents the number of SNVs in each gene, and the color of the bubbles represents the significant level of enrichment, one-sided hypergeometric test was used for statistics. We manually examined genes associated with tissue-specific phenotypes from the HPO database and marked by a black rectangle box. c Expression pattern of top 3 genes in enrichment result of each tissue. d Proportion of pathogenic SNVs predicted as tissue-specific splice altering in different tissues. Only genes that have a p-value < 0.05 in enrichment were included. The box extends from the first quartile to the third quartile of the data, with a line at the median. The dashed line represents the median proportions of SNVs in each tissue. e Number of tissue-specific splice-altering SNVs grouped by pathogenic classifications on TTN gene in different tissues. f Genome coordinate and Tissue z-score of SNVs on a sub-region of TTN gene. SNVs are labeled with ClinVar annotation. Panel a, created with BioRender.com, was released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license.

Next, we applied SpTransformer to all ClinVar SNVs to investigate tissue-specific splicing alterations and their association with disease clinical manifestations. We hypothesized that tissue-specific splice alterations in certain genes might be a vital contributor to the corresponding clinical manifestations. We subsequently identified the top 5 expressed genes with tissue-specific splicing alteration enrichment for each tissue (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 8, “Methods”). We observed a noteworthy correlation between tissue-specific splicing alterations and the corresponding disease manifestations (Fig. 4b, box highlighted, Supplementary Data 2). Notably, the tissue-specificity was not predominantly influenced by gene expression (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 9). In addition, the predictions of SpTransformer allowed us to evaluate the overall contribution of splicing alterations to disease across different tissues, thus we calculated the proportions of tissue-specific splice-altered SNVs in each tissue. We observed that the proportions of tissue-specific splice alterations for known pathogenic variants varied considerably across different genes and tissues (Fig. 4d). It is worth noting that both Blood and Skin, which are considered the most clinically accessible, displayed lower proportions of tissue-specific splice alterations compared to the median average across all tissues. This observation suggests that Blood and Skin may not be suitable alternatives for estimating splicing events in other tissues.

To further examine tissue-specific splice alterations of individual genes, we conducted a detailed analysis for the heart-specific splicing-alteration enriched gene TTN as an example. SpTransformer identified over 300 tissue-specific splicing alterations of TTN in both muscle and heart, while few tissue-specific splicing alterations of TTN were identified in other tissue types (Fig. 4e, f). The TTN gene encodes the titin protein, which is a major constituent of striated muscle proteins and is essential for sarcomere assembly, development, elasticity, and signaling33. In addition, we observed a large proportion of (likely) pathogenic SNVs labeled by ClinVar in the tissue-specific SNVs for TTN, suggesting a high consistency between the predicted tissue-specific splicing alterations and disease manifestation. In fact, splicing variants of the TTN gene have been reported to cause various Mendelian diseases in the heart, such as dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), early-onset myopathy with fatal cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome (BrS), as well as muscle dystrophies like limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMDs) and tibial muscular dystrophy (TMD)34,35,36,37,38,39,40. The identification of numerous tissue-specific splicing alterations in the heart further supports the capabilities of the SpTransformer algorithm.

We also probed the top genes that were enriched across different tissues in Fig. 4b. For instance, the DMD gene, which encodes dystrophin, undergoes mutations in neuromuscular disorders such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy. These disorders are associated with cognitive impairment41 and loss of muscle tissue42. Pathogenic SNVs in different DMD regions have been predicted to exhibit different tissue-specific effects (Supplementary Fig. 10). In a particular example, SNVs (rs1556880354 and rs2149245738) around exon 51 were predicted to be brain-specific, which aligned with previous studies that exon 51 is strongly associated with two brain-specific isoforms of DMD43. Lastly, the NF1 gene, which exhibits various isoforms resulting from alternative splicing, presents differential expression in muscle, blood vessels, or other cell types44,45,46. In our results, NF1 exhibited enrichment in muscle, blood vessels, adipose tissue, and skin (Supplementary Fig. 10), which is consistent with existing knowledge of NF1 mutation-induced tumorigenesis in these tissues46.

Together, these results suggest that SpTransformer has the capability to discern sequence features unique to tissue-specific isoforms of genes associated with disease clinical manifestations. Moreover, the SpTransformer annotation provided mechanistic insights for numerous VUS labeled in ClinVar, specifically regarding tissue-specific splicing alterations (Fig. 4e), suggesting SpTransformer as a powerful tool to be used for genetic diagnosis and VUS interpretation purposes.

Enrichment of brain-specific splicing alterations in multiple brain disorders

Large-scale sequencing studies have been conducted on patients with brain disorders such as ASDs, SCZ, and BD, and protein-coding mutations of genes involved in neuronal activities have been mapped out47,48,49. To evaluate the potential clinical impact of brain-specific splicing alterations, we applied SpTransformer to predict splicing alterations in 11,986 ASD cases and 10,988 ancestry-matched controls, 24,248 SCZ cases, 3402 parent-proband trios and 97,322 controls, and 14,210 BD cases and 14,422 controls, respectively. Figure 5a summarizes the statistics including case/control samples, and analyzed SNVs. related genes and SNVs passed the filter. We assessed the number of predicted splicing alterations across different gene regions and identified a large number of splice-altering SNVs in gene regions and mutation types beyond splice sites, e.g., intron, synonymous, nonsense and missense mutations, which underscores the potential disorder-causing role of splicing alterations outside splice sites (Fig. 5b). In the absence of direct annotations for SNVs from the disorders dataset, we cross-validated our results with ClinVar pathogenicity annotations. Here we hypothesized that a benign SNV should not alter splicing and thus, any benign mutation predicted as splicing-altering was considered false positive. Consequently, among all filtered splicing altering SNVs (ΔSplice > 0.27 and odds ratio > 3.5) also recorded by ClinVar, the false positive rates were 7.84% (59 of 753) for ASD, 0.37% (8 of 2158) for SCZ and 4.11% (86 of 2090) for BD (Supplementary Fig. 11). More importantly, across all tissue types, only brain-specific splice-altering SNVs were significantly enriched in all three types of brain disorders (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 12). This highlights the contribution of brain-specific splicing alterations as a common mechanism to various brain disorders.

a Statistical data for the three analyzed databases. b Splicing effect prediction for different variant types in the three brain disorder datasets: ASC, SCHEMA, and BipEx. c Enrichment of tissue-specific splicing alterations in ASD, SCZ, and BD across five tissues. A two-sided z-test for two groups was performed. The dashed line represents threshold powers for p = 0.05. d Number of tissues showing expression for genes filtered by brain-specific splicing altering SNVs in the case group. e Enriched GO term for genes in (d) that are expressed only in brain tissue (left) and those expressed in 11–15 tissues (right). f Network view of enriched biological processes of genes carrying brain-specific splice-altering SNVs from case group in three brain disorders. g Detailed visualization of genes enriched in GO pathway GO:0007610 “Behavior” in three brain disorders.

To gain deeper insights into the genes harboring brain-specific splice-altering SNVs, we first checked if these genes were all brain-specifically expressed. To our surprise, we observed a bimodal distribution on the cross-tissue expression of these genes (Fig. 5d). We then carried out a gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and found that the genes under different expression patterns showed distinct pathway enrichment (Fig. 5e). Those genes specifically expressed in the brain showed an explicit relation with synaptic signal, and were found to be associated with brain and mental disorders (Supplementary Fig. 13a). On the other side, the genes expressed in 11 to 15 tissues showed functional enrichment in cytoskeleton organization (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 13b). For instance, DCTN1, a gene that encodes a subunit of dynactin, has an essential role in binding microtubules and the molecular motor, and shows cytoplasmic and nuclear expression in most tissues. This gene is known to be associated with neurodegeneration including Perry syndrome50, and BD. We also found SHANK3, a scaffolding protein found in excitatory synapses, which has been reported to be associated with severe cognitive deficits including language and speech disorder and ASD51. Furthermore, epigenetic dysregulation of SHANK3 has been linked to an increased susceptibility to ASD52. This analysis underscores the contribution of brain-specific splicing alteration of cytoskeleton-related genes to multiple brain disorders.

Next, we compiled all enriched pathways in a network view. As expected, the majority of biological pathways were shared across all three brain disorders. These pathways encompassed critical aspects such as brain development, synaptic signaling, neuronal system, and behavior (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Data 3, and Supplementary Fig. 14). Notably, despite sharing common pathways, the three brain disorders remained associated with different brain-specific splicing-altered genes (Fig. 5g). We then selected “Behavior” (GO:0007610) as a study case and manually verified if the genes depicted in Fig. 5g had been previously reported in other publications. Consequently, most of the genes identified by SpTransformer had been previously reported to be associated with corresponding disorders (Supplementary Fig. 15 and Supplementary Data 4). Thus, we believe that in addition to considering only gene expression, tissue-specific splicing is also crucial in clinical diagnosis.

We further investigated the consistency between genes highlighted by brain-specific splicing and other ASD-associated genomic features. For instance, a previous study by Fu et al. reported 72 ASD-associated and 373 neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD)-associated genes based on an analysis of protein-truncating variants53. Interestingly, the top 300 genes identified by our SpTransformer analysis of the ASD dataset showed only a small overlap with the genes reported by Fu et al. (Supplementary Fig. 16). Although not all those genes were investigated, our analysis did find evidence of associations between ASD and genes out of overlap. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating tissue-specific splicing patterns into the investigation of ASD genetics in order to better understand the missing inherence of this disorder.

Taken together, the findings of SpTransformer underscore the importance of investigating brain-specific splicing dysregulation as a disorder-causing mechanism for brain disorders, which holds great promise for advancing our understanding of these conditions and developing targeted therapies.

Mechanistic insights of diabetic nephropathy (DN) revealed by kidney-specific splicing alterations

Having established the SpTransformer model through GTEx, ClinVar, and multiple brain disorder large datasets, we next generated both whole exome sequencing (WES) data from blood samples and RNA-seq data of renal biopsies for an independent Chinese cohort of 95 patients with biopsy-proven DN, and applied SpTransformer to prioritize the genetic contributors to DN (Fig. 6a). DN is a severe complication of diabetes, and the leading cause of end-stage kidney disease. While clinical evidence suggests a genetic component to DN, the genetic variations related to aberrant splicing that confer disease risk remain largely unknown. Therefore, we sought to validate the SpTransformer model using matched RNA-seq data, and to explore potential mechanisms that might contribute to disease risk through kidney-specific splicing alterations. Initially, we carried out the standard quality control procedures for WES data derived from DN patients, taking into account only those variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of less than 0.01 in Asia. Six thousand seven hundred forty-three SNVs were subsequently classified as splicing affecting the cutoff Δsplice > 0.27. Then, 47 of them corresponding to 46 genes were classified as kidney-specific splice-altering SNVs, which were then subjected to downstream analysis (Fig. 6b). To validate the kidney-specific splice-altering SNVs predicted by SpTransformer, we used the matched renal tubule RNA-seq data. We only considered those SNVs that were present in different alleles among the patients in our cohort, and that had sufficient RNA-seq coverage in the region of interest. Ten unique, aberrant splicing events were validated through matched RNA-seq out of 12 predicted kidney-specific splice-altering SNVs, yielding a validation rate of 83% (Supplementary Fig. 17). For example, a G-to-A mutation in the CLCNKA gene created an aberrant splice site in an intron (Fig. 6c), which subsequently resulted in a partial intron retention. The CLCNKA gene is predominantly expressed in the kidney, and the protein encoded by it is involved in transcellular chloride transport and plays a role in the maintenance of body salt and fluid balance54. Disruption of this gene in mice has been shown to induce nephrogenic diabetes insipidus55. On the other hand, a T-to-G substitution near an exon–intron junction in the BTN3A2 gene caused exon skipping (Fig. 6d). This variant was predicted to disrupt splicing specifically in the kidney, lung, and small intestine. The BTN3A2 gene, which is expressed in multiple tissues, encodes a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Previous analyses have identified mutations in BTN3A2 as potential markers for immunoglobulin A nephropathy56.

a Overview of DN patients involved and samples collected for SpTransformer prediction and RNA-seq-based validation. b Flow chart showing the filtering steps of kidney-specific splicing variants for variants called directly from WES data. c, d Examples of heterozygous variants predicted as kidney-specifically splice altering validated by matched renal tubule RNA-seq. SpTransformer prediction on WES identified variants (upper) and sashimi plot of matched RNA-seq data (lower) for CLCNKA (c) and BTN3A2 (d) gene. e Top ten GO terms enriched from genes harboring kidney-specific splicing SNVs. f Top ten terms enriched in the DisGeNet database from genes harboring kidney-specific splicing SNVs. a Created with BioRender.com, was released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license.

To analyze the potential mechanisms underlying the genetic risk for DN behind these genes, we performed a GO enrichment analysis and a disease terms enrichment in the DisGeNet database. The 46 genes were utilized. The most significant GO terms were reflective of kidney-specific biological processes including “renal system process” and “arachidonic acid metabolism” (Fig. 6e), while the DisGeNet terms reflected “nephrogenic diabetes insipidus” (Fig. 6f). Notably, arachidonic acid (AA) is a ω − 6 polyunsaturated fatty acid and its metabolites play a critical role in the pathobiology of diabetes57. In the kidney, prostaglandins (PG), thromboxane (Tx), and leukotrienes (LTs) are the major metabolites generated from AA57,58. An increased level of these metabolites results in inflammatory damage to the kidney57. Our findings in this pathway suggested that aberrant splicing may represent a potential mechanism underlying the abnormalities in AA metabolism in DN.

Together, these results support the reliability of SpTransformer prediction and enable us to explore DN candidate pathogenic variants from the perspective of splicing alterations. These findings are concordant with the known pathology of DN and highlight key genes harboring kidney-specific aberrant splicing that may contribute to renal dysfunction in DN. In summary, the application of SpTransformer helps effectively prioritize disease-associated mutations and sheds light on unresolved disease mechanisms.

Discussion

Predicting RNA splicing directly from sequence data has been a long-standing challenge in the field. To address this, we have developed a novel computational framework, SpTransformer, utilizing an attention-based deep-learning neural network. SpTransformer stands out as the pioneering method to employ a transformer model for predicting RNA splicing with tissue specificity. This transformer architecture benefits SpTransformer from large-scale, cross-species datasets. In addition to predicting splicing events, SpTransformer emphasizes the tissue specificity of these events, an aspect often overlooked by most existing splicing prediction methods. This unique feature enables a more comprehensive understanding of the splicing landscape across different tissue types. SpTransformer has been successfully applied to mutation databases and disease-specific datasets, identifying tissue-specific splicing alterations and their associated disease manifestations.

Splice-altering mutations make up an essential class of known disease-causing mutations, and accurate prediction methods are crucial for interpreting VUS and pathogenic variants in clinical diagnostic tasks. While ideal scenarios would include RNA-seq profiles of diseased tissue together with the genotyping data, practically most disease-manifested tissues are not accessible or easily accessible. Nonetheless, we identified genes enriched in mutations that may alter splicing in various tissue types, which provides stronger supporting evidence for clinical interpretation of VUS pathogenicity in the relevant tissues.

As WGS becomes more widely adopted, there is an increasing need for accurate pathogenicity prediction of mutations in the noncoding regions. Through extensive analysis of the ClinVar database, we identified a significant proportion of intronic pathogenic/like pathogenic mutations that may affect splicing. Therefore, the application of splicing models, such as SpTransformer, may provide valuable information for pathogenicity prediction and interpretation of variants in the noncoding region.

The success of SpTransformer in achieving tissue specificity is attributed to the application of NLP models and large datasets. Although previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of deep convolutional networks in this domain, the convolution and transformer architectures we designed have several advantages. First, the tissue-specific splicing is presumably achieved through CREs as represented by sequence motifs. The attention mechanism in the transformer can help capture such CREs much more effectively. Second, transformers have demonstrated advantages in capturing distal information and can perform better at capturing CREs located far away. Third, we utilize RNA-seq data from four distinct mammalian species. This approach enables our model to discern similarities and homologies of splicing sites across species. Finally, we feed the GTEx data and evolutionary data into two convolution encoders before the transformer to extract different layers of splicing information, which supports the model with more comprehensive but structured input. Based on these considerations, our dual-encoder Transformer model, Spransformer, has exhibited a clear advantage over other state-of-the-art methods in tissue-specific splicing prediction on the GTEx dataset. To the best of our knowledge, SpTransformer is the first application of the transformer deep learning architecture that achieves remarkable performance in tissue-specific splicing prediction.

The limitations of the model come in several aspects. First, there is room for increasing the training data and including more rare splicing events. Currently, our splicing annotation is based on annotation from GTEx common splicing events, which does not account for splicing variability at the individual level. Second, the model’s inclusion of tissues is still limited. While the SpTransformer model handles approximately 15 different tissue types with high accuracy, its performance decreases as the number of multitask events in the model increases. Additionally, tissue-specific splicing is, in reality, a combined result of the splicing events of all single cells in the tissue. However, experimental technologies that measure splicing at the single-cell level are currently limited. Therefore, we envision the collection of more individualized and cell-specific splicing events can potentially enhance the deep learning model and enable more precise splicing predictions in the future.

Methods

Data representation

The input for the model is pre-mRNA sequences. The nucleotides A, C, G, and T are one-hot encoded, represented as [1,0,0,0], [0,1,0,0], [0,0,1,0], and [0,0,0,1], respectively. These encoded nucleotides are combined to form a 4 × N matrix, where N stands for the length of the sequence. [0,0,0,0] are used for padding sequences with insufficient length or to present “unknown” nucleotides in unclear regions. The model utilizes this input matrix to capture sequence features. Specifically, we denote the length of the input sequence as N = Ncontext + Ntarget + Ncontext, where Ntarget represents the length of the target region that we aim to predict, and Ncontext represents the length of the flanking sequence to each side of the target region, which we consider as “sequence context”. For the training and testing data, each nucleotide in the target region is assigned a splice label set [SN, SA, SD] and a numerical tissue usage label set [S1, S2, …, St]. Splice labels SA, SD, SN represent the possibility that a position is an “acceptor”, “donor” or “neither” (not a splice site), respectively. Tissue usage labels S1, S2, …, St, where t is the number of tissues, indicate the possibility that a position is used as a splice site in a certain tissue. These labels range in [0,1]. Consequently, the model produces a matrix with the shape of (3 + t) × Ntarget as its output. We applied Ntarget = 1000, Ncontext = 4000, and t = 15 in our work. Specifically, for an RNA sequence of length 9000 nt, SpTransformer utilized the sequence context to predict splicing sites and their corresponding usage in 15 tissues for the central 1000 nt sequence.

Data collection and labeling

We collected splicing data from various sources, including the GTEx V822 database and an independent large-scale RNA-seq dataset covering various species. GTEx V8 (dbGaP Accession phs000424.v8. p2) consists of 838 donors, providing 17,382 samples from 53 tissues and two cell lines. To obtain meaningful splice sites and the corresponding tissue usage ratio, we processed the exon-exon junction read counts file from the dataset for 15 representative tissue types. Initially, sequences around splice junctions in the GRCh38 reference genome were extracted. The base preceding and following each splice junction (i.e., the 5’ and 3’ ends of exons) were defined as splice sites. Only samples from the 15 selected target tissues were considered. A splice site position was labeled as “acceptor” or “donor” label if it was supported by any sample and had no conflict. The splice site at the exon start site was labeled as “acceptor”, and the splice site at the end site was labeled as “donor”. All other positions were labeled as “neither”. Subsequently, the tissue usage label was calculated for each splice site, representing the proportion of samples belonging to the tissue that contained corresponding splice junctions, i.e.,:

The tissue classes analyzed in this study included: adipose tissue, blood, blood vessels, brain, colon, heart, kidney, liver, lung, muscle, nerve, small intestine, skin, spleen, and stomach, which were frequently investigated for splicing events or had abundant samples in GTEx V8 dataset. The relationship between the class labels in SpTransformer and detailed tissue types in the GTEx was documented in Supplementary Data 1. The SpTransformer code frameworks also support other combinations of tissue types. During the training and testing processes, any splice site with a maximum usage label of less than 0.05 across all tissue classes was excluded and re-labeled as “neither” class.

The independent RNA-seq dataset underwent similar processing steps. We utilized mammalian organ transcriptomes, including samples from humans, rhesus macaque, mice, and rats. For additional species, the genes that show orthology or paralogy to human genes in the test dataset were excluded. A splice site was identified if it was in the gene body and supported by at least one split read in each of at least two different samples.

The dataset only included tissue usage labels for 4 tissues: Brain, Heart, Liver, and Kidney. Hence, the label for each nucleotide was represented as [SN, SA, SD, S1, S2, S3, and S4], in accordance with the aforementioned definition. Despite the presence of additional tissue samples in the data source, such as forebrain or hindbrain, they were omitted due to their absence in all species. Since there were directly accessible RNA-seq data, the tissue usage label was estimated by splice site strength calculated with SpliSER59. The dataset was partitioned following the same strategy as the GTEx dataset. The part of the training data was considered an extension of the training dataset, while the test data segment remained unused.

We chose sequences from chromosomes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10–22, X, and Y to create the training dataset. Sequences belonging to chromosomes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 were compiled as the testing dataset. To ensure the test data was not exposed in training data, we cross-referenced the sequence strands with the Ensemble database (release 110)60. We excluded gene sequences that have paralogs from the testing dataset. Despite splitting the two datasets independently, we made sure that there was no overlap between the training and testing data after the steps to split data by chromosomes and paralogs.

To compile the datasets, the pre-mRNA sequences of each gene were extracted. For genes with multiple transcripts, the extracted sequence began from the most upstream site observed across all transcripts and ended at the most downstream site observed across all transcripts. Subsequently, each sequence was divided into blocks of length 1000 nt. Blocks that did not contain any splice sites were discarded. For each remaining block, the flanking sequence with 4000 nt + 4000 nt and the corresponding 1000 nt label was packaged as a single training (testing) data entry.

SpTransformer model structure

SpTransformer is a large deep neural network model that consists of two main modules: an encoder module and a transformer module. The encoder module incorporates a series of residual networks, known as ResBlock, with inspiration originating from classic ResNet structure61 in computer vision tasks. Previous studies have shown the effectiveness of convolution-based methods in capturing sequence or “motif” features in DNA/RNA sequences7,62. However, as the depth of the network increases, a brutal stack of convolution layers may lead to a rapid decrease in the network’s accuracy due to the vanishing or exploding gradient problem61. A residual block is composed of a series of convolution layers, interspersed with several batch-normalization layers and RELU activation function layers. Stacking these residual blocks can help mitigate the gradient issue and enhance the model’s ability to handle complex features61.

The second component of our model mainly consists of a Sinkhorn Transformer module and a multi-layer perception module. Transformers have become a fundamental component in the field of modern NLP63. Their “Attention” mechanism efficiently solved sequence-based tasks such as the Named Entity Recognition problem, which is similar to our challenge of recognizing splicing sites based on RNA sequences. The Sinkhorn Transformer64 is a variant of the transformer model that is designed to handle sequences of considerable length (8192 nt in our model).

The architecture of our model is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The input is an RNA sequence of length N = Ncontext + Ntarget + Ncontext, where Ntarget denotes the length of the target sequence, and Ncontext represents the sequence context of the target region (Ncontext = 4000 in our pipeline). The parameter L dictates the number of channels in each convolution layer, with L1 = 192 and L2 = 64 used in this study. The convolution layer in ResBlocks is characterized by parameters L, W, and D, which represent the number of channels, kernel width, and dilation, respectively. Following the calculation of the encoder module, a concatenation, and a truncation operation are applied to ensure that the input to the attention module does not exceed a length of 8192. The Sinkhorn Transformer module has 256 channels, 8 attention heads (including two local attention heads) per layer, and eight layers of depth. The final output is a (N × 3) shaped matrix and a (N × 15) shaped matrix, representing splice site prediction and tissue usage prediction, respectively.

The hyperparameters were selected by multiple processes: 1) Ntarget and Ncontext: the determination of these parameters was influenced by the model’s architecture. While our goal was to allow the model to process long sequences, practical constraints—such as GPU memory limitations—necessitated a compromise. In that case, we set Ntarget = 1000, Ncontext = 4000 so that each target nucleotide has at least 4000 + 4000 available context information, taken considering that 8000 nt context is enough for the model (Supplementary Fig. 3). 2) The dimension of encoder layers was gained by grid-search in {32, 64, 128, 256}. Multiple hyperparameters of the transformer module were also tried, including: layers of transformer = {4, 6, 8, 10}, and number of attention heads = {6, 8, 10}. During this process, batch size = 12 and learning rate = 0.001 were used in order to keep consistent with SpliceAI. 3) Other parameters was selected from: batch size = {6, 12, 18, 24}, learning rate = {0.01, 0.005, 0.001, 0.0001}, decay factor of learning rate = {0.9, 0.7, 0.5}. Those options were established in reference to previous publications, suggestions from Transformer models, and the memory limitations of GPUs. From all those options, the combination with the best performance on the validation dataset was subsequently used.

Further details of input and output have been provided in the “Data representation” section. Different measurement was applied to the output scores. For splice site prediction, we applied a Softmax activation function to produce probability prediction of “Acceptor”, “Donor”, and “Neither”. For tissue usage prediction, we applied a sigmoid activation for each tissue type.

Model training and testing

SpTransformer underwent two stages of training. In the first stage, two convolution-based encoder modules with identical structures were trained separately. One module learned weights from the GTEx training dataset, while the other module learned weights from the excessive training dataset, due to the fact that the two datasets have different label formats. To accommodate the different data formats of the two datasets, temporary convolution layers with 1 × 1 kernel size and particular output channels (18 and 7, respectively) were appended to each convolution module to align the outputs with the labels. The output of the temporary layers was used directly for loss calculation and back propagation. The two modules were assigned 128 and 64 channels (i.e., the parameter “L” in Supplementary Fig. 1), respectively, based on the difference in tissue numbers. In the second stage, the temporary layers were removed. The two modules with frozen parameters were directly integrated into a 192-channel convolution network, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The whole network was then trained on the GTEx training dataset to get the final model. This approach enabled SpTransformer to learn from multiple datasets with similar biological meanings but different data formats, minimizing the need for extensive coding or conversion when differently sourced data was received. Despite both datasets being under the sequence model, the diverse splicing representations and distinct data content encourage the deep model to comprehend latent sequence features from various aspects, akin to a visual model examining a human face in multiple ways. The strategy improved the model’s performance compared to only using one dataset, demonstrating the potential to integrate diverse bioinformatics data for a single task.

Special loss functions are used in the backpropagation of deep learning. In the first stage, the loss function is:

Each sequence in the training dataset is a contiguous nucleotide sequence of length n. The i-th position has a splicing label Ai and a tissue-usage label Bti for T different tissues. For this position, the model outputs si for splice site prediction, and outputs uti for tissue-usage prediction. For splicing prediction, we compute the categorical cross-entropy loss, as it is a multi-class classification task. In contrast, for tissue-usage prediction, which is a multi-label classification task (meaning one sample can belong to multiple classes), we calculate the Binary Cross-Entropy loss. We apply mean reduction for the two loss functions.

The loss function above is sufficient for the encoders to learn basic sequence patterns. However, as the number of supported tissues increases, new challenges emerge. First, models struggle to learn the features of different tissues in a balanced manner during the training process, occasionally demonstrating superior predictive performance for specific tissues only. Second, there is a relative scarcity of samples with strong tissue specificity compared to those with weak tissue specificity. This imbalance leads to models tending to produce similar tissue usage scores for splice sites. During the second stage, we apply a special loss function, in order to persuade the transformer module to overcome these difficulties:

The formula calculates the weighted geometric mean for loss of tissue usage. The idea is motivated by previous computer vision research65. We use this method to encourage the model to balance the performance on multiple tissues and pay attention to those tissues that harder to classify. For the i-th position of the sequence, a weight wi was multiplied to encourage the model to pay more attention to splice sites with stronger tissue specificity. wi related with the variance of tissue-usage labels of i-th position.

The model was trained for 12 epochs in each stage. Adam optimizer was used to minimize the combined loss. The learning rate was set to 0.005, and was multiplied by 0.7 after every epoch.

Model performance evaluation and ablation test

We evaluated the performance of SpTransformer on two tasks using the compiled test dataset: 1) splice site prediction in long sequences: the model took each pre-mRNA sequence as input and identified every splice acceptor and donor within a target region of 1000 nt. Given that most positions in the sequences are not splice sites, we computed the top-k accuracy and the area under the precision-recall curve (AU-PRC) for splice site prediction. The top-k accuracy was defined as follows: if a sequence has k positive positions that truly belong to the class, a threshold is selected so that exactly k positions are predicted to be positive. The fraction of these k predicted positions that truly belong to the class is reported as the top-k accuracy. We calculated the top-k accuracy and AU-PRC value for the acceptor and donor classes separately, and reported the average performance of the two classes. 2) Tissue usage level prediction: the model was tasked with predicting the usage level in each of the 15 tissue classes for each position of the sequence. Given the absence of a widely accepted “tissue usage” protocol, we divided all splice sites in the test dataset based on their tissue usage label. Since most tissue usage labels were close to (or equal to) 0 or 1, we defined a tissue usage label greater than 0.5 as “high usage”, while the remaining sites were classified as “low usage.” The usage was set to 0 if a position was not a splice site. The model was then tasked to classify the usage of each position in the test dataset. Furthermore, positions that did not pass the top-k threshold in task 1 were forcibly masked as negative in the prediction result. We calculated AU-PRC for each tissue class. According to the two tasks outlined above, we conducted a comparative analysis, including an ablation test to highlight the advantages of our method. Firstly, we prepared three different versions of the SpTransformer model: SpTransformer-noextra, which was trained only on the GTEx training dataset; SpTransformer-extra1, which used an extra training dataset of two species, human and macaque; and SpTransformer, which used the full training dataset of four mammalian species. All versions were trained with the same configuration.

Secondly, we applied the published version of SpliceAI to the tasks for comparison. Furthermore, we prepared a similar CNN-based network, named as SpliceAI-modified. The key difference was a specific alteration: the output channel number of the final convolution layer was adjusted from 3 to 18. This modification enabled the model to predict tissue usage at each splice site. The modification was a permissible adjustment within the conventional design framework of CNN. This network was trained on the GTEx dataset with the same hyperparameter and loss functions as the first stage of SpTransformer. We also retrained SpliceAI on our training dataset using the same hyperparameters as the original version, named SpliceAI-retrained. We then included the published version of Pangolin. Pangolin supports the prediction of four tissues (brain, heart, liver, and testis) and does not distinguish between acceptor and donor. Thus, the Brain, Heart, and Liver models of Pangolin were used. The maximum splice scores of them were used in task 1. The tissue scores of them were used in task 2. It is worth noting that SpliceAI-modified has a remarkably similar structure to Pangolin, despite the differences in their last output layers. SpliceAI-modified predicts splicing effects across 15 tissues using a single model, whereas Pangolin utilizes four distinct models, each dedicated to a specific tissue.

Finally, we adapted the task for earlier methods that were not entirely compatible with our tasks. MMSplice, HAL, and MaxEntScan were designed for classifying a single position with short flanking sequences. We modified the input format to enable them to predict each position of the long sequences individually. For each position, the lengths of input sequence were carefully selected based on the recommendations provided by their respective publications. Since HAL does not score 3’ splice sites, we excluded the “Acceptor” class when evaluating HAL. The “MMSplice_MTSplice” tool is a combined model where “MMSplice” predicts splice sites and “MTSplice” predicts tissue-specific usage of those splice sites. During testing, we evaluated MMSplice in two different scenarios: the full dataset, as well as a simpler task where it was restricted to predicting positions within a 20 nucleotide range of each splice site, rather than the whole sequences. The performance on the simpler task was marked as “MMSplice-short”. MTSplice was able to predict usage scores in 56 detailed tissue types. We took the maximum score of corresponding types as the prediction of 15 classes in our dataset. Since “MMSplice-short” exhibited an advantage against “MMSplice”, MTSplice was also tested on the restricted task.

We further investigated the importance of context in flanking RNA sequences of splice sites. All splice sites in chromosome 1 were extracted from the GTEx test dataset. Several test routines were performed after masking flanking sequences over certain values of the range. AU-ROC was calculated for each test routine in the same way as performance testing before (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Estimate sequence weights by in-silico mutagenesis

To identify important regions within the input sequences, we performed a procedure referred to as “in silico mutagenesis”. The “mutagenesis weight” of a nucleotide with respect to a splice site is defined as follows: Let sref denote the splice (or tissue usage) score of the target splice site. The score is recalculated by replacing the nucleotide under consideration with A, C, G, and T. Let these scores be denoted by sA, sC, sG, and sT, respectively. The mutagenesis weight of the nucleotide is estimated as:

Under our hypothesis, a larger mutagenesis value indicates that “the splice site is more likely to be lost if the position is mutated”. We calculated the difference between the maximum and mean tissue usage values across all 15 tissues for each splice site in the GTEx dataset. Those with the top 1% difference value were selected, including 2754 splice donors and 2670 splice acceptors. For each selected splice site, in silico mutagenesis was performed for the sequence from 80 nt upstream to 20 nt downstream of the site. For each sequence, let maxsref denote the maximum sref value among all the 15 tissues. For each tissue and each sequence, all subregions with 8 nt length and with average mutagenesis weight greater than maxsref were extracted. The motif analysis tool XSTREME28 was utilized to enrich motifs from those extracted subregions. Multiple associating motifs were enriched for each tissue through the outlined methodology. Despite the different PWM matrices, the motifs were treated as the same term if their IUPAC codes (given by XSTREME) have a Levenshtein Distance not greater than 1.

Quantifying splicing change resulting from variants

In order to quantify the splicing alterations caused by SNVs, we calculated the difference in scores between the original sequences and the alternated sequences. Firstly, we predicted the 2R + 1 length of the reference sequence surrounding the mutation (R represents the length of flanking nucleotides on each side, and was set to 100 by default in our analysis) using SpTransformer. We then used the alternative sequence for prediction, resulting in prediction scores for each position of the sequence. Regardless of the “not a splice site” class, scores for each class were represented by vectors in the shape of (2R + 1) × 1. For reference and alternated sequence, there were scores named Refacceptor, Refdonor, Altacceptor, Altdonor, Refbrain, Refheart, Altbrain, Altheart, …, for two splice site types and 15 tissue types. We evaluated the following quantities, using brain tissue as an example:

Δscore for other tissues was calculated in the same way, where abs() refers to the function to calculate the absolute value for each position, and max() is the function to find the max value in the vector. We defined ΔSplice as the max value between ΔAcceptor and ΔDonor to quantify the effect of splice alteration caused by a variant:

The Δscore for each tissue, for example, ΔBrain, was processed to quantify the change in tissue usage.

Quantify tissue-specificity by tissue z-score

To quantify tissue-specificity, we designed a z-score. We created a reference mutation set with GTEx SNVs data. Upon checking the GTEx Genotype calls vcf file, we identified a total of 734,509,842 variants. We selected SNVs that met the following conditions: 1) For each tissue, there should be at least one available RNA-seq data from an individual carrying the SNV. 2) For each tissue, there should be at least one available RNA-seq data from an individual not carrying the SNV. 3) Within a 100nt range of the SNV location, a significant change in splice site usage, either increase or decrease, should be observable across all tissues when comparing RNA-seq data between individuals with and without the SNV. The “low” and “high” were under the same definition as those used in the training dataset. Finally, we filtered out 27,843 mutations that cause splice alterations in all tissue classes. These mutations were expected to have minimal impact on tissue specificity, and their Δscore was used to build a reference distribution hereafter. SpTransformer predicted the ΔSplice score and tissue Δscores for each mutation. A tissue z-score was then calculated based on the following formula. Here we use adipose as an example.

Here we denote μ as the average values, σ as the standard error, and Zi representing the adipose tissue z-score for the i-th mutation.

The distribution of the tissue z-score for each tissue was defined as the reference distribution mentioned above (Supplementary Fig. 7). For any new SNVs analyzed, we similarly calculated its z-score using previously calculated μtissue and σtissue. For each tissue, we consider any real SNVs with a tissue z-score greater than X% of the reference distribution to be tissue-specific. In all analyses in this work, X = 99 was used by default.

Quantifying gene expression level by ASCOT database

We employed the normalized area under the curve (NAUC) as a measure of gene expression levels. The introduction of NAUC by ASCOT66 enables users to explore gene expression in a wide range of cell types and tissues. The dataset was derived from the GTEx project, which included 9662 human RNA-Seq samples across 53 tissues. In our study, we calculated the average NAUC value across the corresponding tissue types for each of the 15 tissue classes. The correlation between the tissue classes and their corresponding detailed tissue types is presented in Supplementary Data 1. We classified gene expression into “Low” (0–1 NAUC), “Moderate” (1–20 NAUC), and “High” (over 20 NAUC) according to the recommended standard. This classification was used during analysis to exclude genes with “Low” expression in the tissues of interest from our investigation. All the gene expression values presented in the figures were based on the NAUC values.

Finding splicing altering SNVs in the ClinVar database

We utilized SpTransformer to predict splicing altering variants in the ClinVar database (the 20220917 version with hg38 genome annotation). We analyzed a total of 1,273,053 SNVs. These SNVs were annotated using SnpEff67 and only variants with consequence annotations “splice acceptor variant”, “splice donor variant”, “intron variant”, “synonymous variant”, “missense variant”, and “nonsense” were considered in all analyses. We employed ΔSplice to distinguish variants of different pathogenicity (Fig. 3a). The SNVs were categorized based on their consequence annotations (e.g., “Intron”, “Synonymous”, etc.) and clinical significance labels (e.g., “Benign”, “Pathogenic”, etc.). SNVs with ambiguous labels such as “Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity” or “Likely risk allele” were excluded.

We further utilized SNVs from the ClinVar dataset to establish a score threshold for SpTransformer (Supplementary Fig. 5). The “Strict” panel presents the performance of our SpTransformer model in distinguishing between pathogenic and benign mutations, while the “Soft” panel presents the performance in distinguishing between pathogenic/likely pathogenic/uncertain mutations and benign/likely benign mutations.

The classification cutoff was determined by considering the F1-score, recall, and precision in these tasks. We employed a cutoff value of 0.27, ensuring that the model demonstrated equal precision and recall in the “Strict” task, based on the following three considerations: 1) to specifically investigate splicing events. 2) The F1-score showed only slight differences across a wide range of delta splice values, while recall dropped off more significantly (Supplementary Fig. 5c). 3) In a clinical setting, we had a preference for higher recall over higher precision, in order to identify critical variants. This cutoff value allowed us to discern variants that impact splicing. When analyzing Figs. 4 and 5, the cutoff value served as a filter to identify mutations that have the highest likelihood of being implicated in human disease through their impact on splicing. We also provided other cutoffs for users. E.g., Δsplice = 0.54 for the max F1-score, and Δsplice = 0.09 for distinguishing “likely pathogenic” and “likely benign” mutations. Similarly, a cutoff = 0.32 was chosen for the SpliceAI-retrained model, to reproduce SpTransformer’s result as a comparison (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Enriching genes in tissue-specifically splice-altering SNVs

To identify genes in ClinVar associated with tissue-specific splicing, we performed an enrichment pipeline for SNVs. This pipeline incorporated three filters to identify tissue-specific splicing SNVs: ΔSplice score = 0.27, tissue z-score > 99%, and ASCOT gene expression NAUC > 1. Subsequently, we conducted a hypergeometric test on the genes that contained those predicted SNVs. To validate the association between gene-tissue disease, we referred to the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) database68. For each gene enriched with splicing alterations SNVs, we examined HPO terms for tissue-related phenotypes in the corresponding Mendelian disorders.

Process and analysis of three different brain disorders

We collected variants related to three brain disorders: ASD, SCZ, and BD from three different public databases ASC, SCHEMA, and BipEx, respectively. The ASD data was obtained from the analysis of de novo variants called in family-based data consisting of 6430 probands with ASD and 2179 unaffected siblings, as well as rare variants called in 5556 ASD cases and 8809 ancestry-matched controls. The SCZ data was obtained from the GATK analysis of WES of 24,248 cases and 97,322 controls, as well as de novo mutations from 3402 parent-proband trios. The BP data was obtained from variants called from WES of 14,210 cases and 14,422 controls, post-quality control. Due to limited raw sample data, we were unable to segregate mutations into case and control groups using the GATK pipelines and calculate p-values. Instead, we calculated the odds ratio (OR) using the allele count and allele frequency of SNVs in the case and control samples. SNVs with an OR greater than 3.5 were classified as case SNVs. Following this pipeline, we employed SpTransformer to predict the splicing effect. After prediction, we applied a series of filters: 1) SNVs with ΔSplice greater than 0.27 (the cutoff determined in Supplementary Fig. 5) were considered splice-affecting SNVs. 2) SNVs with brain tissue z-score above 99% and the corresponding genes had moderate expression (NAUC > 1) were finally categorized as brain-specific splicing variants. The two-proportion z-test used in Fig. 5c is a statistical test designed to determine whether the proportions of categories in two group variables significantly differ from each other. In this study, we employed this test to examine whether there exists a larger proportion of brain-specific splicing variants among case SNVs that are related to splicing. Specifically, Group A consisted of all SNVs with OR > 3.5 and ΔSplice ≥ 0.27. while Group B included all SNVs with OR ≤ 3.5 and ΔSplice ≥ 0.27.

We sorted all filtered SNVs by brain tissue z-score and selected the top 300 related genes for each disorder. We applied the online tool Metascape69 for GO terms enrichment analysis, disease–gene association enrichment analysis, and corresponding network figures. We categorized tissue-specific expression patterns based on the ASCOT NAUC values across 15 tissue classes. A gene was designated as having ’brain-specific expression’ if its NAUC value exceeded 1 solely in brain tissue. Similarly, if a gene’s NAUC value exceeded 1 in any other tissue, it was classified as expressed in that specific tissue. We further manually verified whether each gene listed in Fig. 5g had been previously reported to be associated with the respective disorders. Genes were classified as “previously reported” if any publication in PubMed explicitly stated in the abstract, results, or discussion that the gene is associated with the disorders.

DN variant enrichment and RNA-seq validation

We processed WES data from DN patients for downstream analysis. Genomic DNA isolated from whole blood was used for genotyping. Ninety-five DN patients were genotyped using Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit (Agilent Technologies) and sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq3000 with Hiseq3000SBS&Clusterkit. The human kidney tissues used were obtained from DN patients with renal biopsy-proven, sourced from Nanjing Glomerulonephritis Registry, National Clinical Research Center for Kidney Diseases, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing, China. RNA sequencing was performed on micro-dissected tubulointerstitial tissue from 95 patients diagnosed with DN. Total RNA was extracted using an RNAeasy Micro kit (Cat#74,004, QIAGEN Science) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was assessed with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Only samples with RIN scores above seven were used for cDNA production. Qualified total RNA was further purified by RNAClean XP Kit (Cat A63987, Beckman Coulter, Inc. Kraemer Boulevard Brea, CA, USA) and RNase-Free DNase Set (Cat#79254, QIAGEN, GmBH, Germany). Strand-specific, polyA-enriched RNA-seq libraries were generated using the VAHTS Stranded mRNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina. FastQC (v0.11.9) was used for quality control. STAR (v2.7.8a)70 was used for alignment against the human Grch38 assembly. Transcripts of low quality were filtered out, and the read counts were normalized to transcripts per million (TPM) within each sample. These values were then log2 transformed (log2 (TPM + 1)). To identify kidney-specific splice-altering SNVs, we performed the following steps: 1) applied the GATK variant caller and standard quality control procedures; 2) retained the SNVs with an MAF of less than 0.01 in the Asian population; and 3) retained the SNVs with an ΔSplice greater than 0.27, a kidney tissue z-score above 95% and the corresponding genes had expression NAUC score > 1 in the kidney. These procedures resulted in 47 kidney-specific splice-altering SNVs corresponding to 46 genes expressed in the kidney tissue (Fig. 6b). We validated these retained SNVs using RNA-seq data, excluding those without sufficient coverage at the mutation site and adjacent exon regions. Following this pipeline, 12 SNVs corresponding to 12 genes were validated. Each SNV was manually checked in IGV browser71 and visualized with the R package ggsashimi72.

Statistical information

Statistical tests are described in the figure captions, main text, and corresponding “Method” sections. To summarize, we used a one-tailed hypergeometric test to enrich tissue-specific splicing-altering SNVs in genes from the ClinVar database. We used a two-sided z-test for two groups to measure the enrichment of tissue-specific SNVs in the three brain disorder datasets. For tissue z-scores defined in the main text, we use sentences like “99% significance” to represent tissue z-scores that are greater than 99% of mutations in the reference distribution. The GO term enrichment analysis (related to Figs. 5e, f and 6e, f) was calculated by Metascape based on the hypergeometric test and Benjamini–Hochberg p-value correction algorithm.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability