Abstract

Crystalline-silicon heterojunction back contact solar cells represent the forefront of photovoltaic technology, but encounter significant challenges in managing charge carrier recombination and transport to achieve high efficiency. In this study, we produced highly efficient heterojunction back contact solar cells with a certified efficiency of 27.09% using a laser patterning technique. Our findings indicate that recombination losses primarily arise from the hole-selective contact region and polarity boundaries. We propose solutions to these issues and establish a clear relationship between contact resistivity, series resistance, and the design of the rear-side pattern. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the wafer edge becomes the main channel for current density loss caused by carrier recombination once electrical shading around the electron-selective contact region is mitigated. With the advanced nanocrystalline passivating contact, wafer edge passivation technologies and meticulous optimization of front anti-reflection coating and rear reflector, achieving efficiencies as high as 27.7% is feasible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advancement of wafer-based crystalline-silicon (c-Si) solar cells has substantially reduced the levelized cost of energy in photovoltaic (PV) power generation, enabling cost-effective decarbonization. Global PV deployment has surged over the last decade. Concurrently, the rapid evolution of applications necessitates expedited advancements in solar cell technology to adapt to diverse scenarios, including integration into buildings, vehicles, and aircrafts, where high power generation per fixed area is of primary concern1,2,3,4.

Front and back contact (FBC) solar cell structure has dominated the mainstream PV market and demonstrated high power conversion efficiency (PCE) through the incorporation of passivating contact technologies such as silicon heterojunction (SHJ) and tunnel oxide passivating contact (TOPCon)5,6,7,8,9. Our previous works reported SHJ solar cells with a certified efficiency of up to 26.81%, attributed to the improved passivating contact characteristics10,11,12,13,14. This device achieved a normalized electrical performance (open-circuit voltage (VOC) multiplies fill factor (FF), and normalized by the Shockley-Queisser (SQ) limit of c-Si solar cells, i.e., (VOC × FF)/(VOC,SQ × FFSQ)) of 0.848, with optimized optical performance resulting in a short-circuit current density (JSC) of 41.45 mA·cm−2 15. Richter et al. reported n-type and p-type TOPCon solar cells with efficiency (normalized electrical performance) of 25.8% (0.789) and 26.0% (0.810), respectively, and JSC values approaching 42.87 mA·cm−2 and 42.05 mA·cm−2 16,17,18. While FBC solar cells can achieve excellent results in electrical or optical characteristics individually. However, it is difficult to manifest both in the same device due to the co-constraints existed, leaving FBC solar cells still face limitations19,20. Achieving low current density loss, optimal contact resistivity, and sufficient passivation quality simultaneously poses a vital role in further efficiency improvements21.

Interdigitated back contact (IBC) structures offer the inherent advantage of zero-electrode shading, as all frontal metal electrodes are positioned on the rear side, maximizing the utilization of incident spectral energy. Moreover, the all-back-contact design alleviates constraints on contact designs for both polarities, thereby reducing the challenge of balancing passivation and contact resistivity22,23,24.

In 2017, Kaneka Corporation in Japan realized heterojunction back contact (HBC) solar cell with an efficiency of up to 26.7% (JSC of 42.5 mA·cm−2)25,26, and recently, LONGi Corporation in China has announced a new record efficiency of 27.30%16. Institute for Solar Energy Research Hamelin (ISFH) in Germany reported a small-area polycrystalline silicon on oxide interdigitated back contact (POLO-IBC) solar cell with an efficiency of 26.1% (JSC of 42.6 mA·cm−2) deploying a laser patterning process27,28,29. These findings indicate that back contact structures indeed enhance optics to support efficiency gains. However, IBC solar cells necessitate optimized structural design to balance charge carrier recombination and transport on the rear side. The thin layers at the hole-selective contact (HSC) and electron-selective contact (ESC) regions are arranged in alternating rows, increasing device fabrication complexity and introducing numerous polarity boundaries. Consequently, IBC solar cells are more susceptible to process-related contaminations and polarity boundary recombination compared to FBC solar cells. Additionally, IBC solar cells are prone to electrical shading effect, resulting in an ineffective collection of partial charge carriers23,30,31,32,33.

In this paper, we exploited amorphous silicon as passivating contact layers and laser ablation as a mass-production technology for fabricating HBC solar cells, achieving a certified efficiency of 27.09%. Rigorous experimental and theoretical validations were conducted for recombination loss, resistive loss, and current density loss. The research offers multiple strategies and guidelines for optimizing structural design and resolving major contradictions within back-contact solar cells.

Results

High-efficiency HBC solar cell

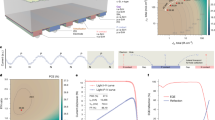

Our HBC solar cell was realized on a large-area Czochralski wafer utilizing a laser patterning technique developed by our team. Figure 1a illustrates the HBC solar cell structure, featuring a textured front surface to minimize reflection loss and a polished rear surface to enhance the secondary or multiple absorption of the photons at longer wavelengths34,35. Additionally, interdigitated HSC and ESC regions with effective insulations in between are precisely patterned on the rear side using a laser ablation technology. Detailed fabrication process of HBC solar cells can be found in “Methods” and Fig. S1. PCEs of 26.74% with total area (ta, 274.3 cm2) and 27.09% with designated illumination area36 (da, 243.0 cm2 for our HBC solar cell), are certified by the ISFH testing institute under standard test conditions (25 °C, an illumination of AM 1.5 G spectrum, and 100 mW·cm−2), as depicted in Fig. 1b.

a Cross-sectional diagram of HBC solar cells. The substrate is n-type crystalline silicon (n-c-Si). The front side features anti-reflection coatings (ARC), and the rear side is divided into four regions, which are HSC, gap, ESC, and HSC + gap. The inserted transmission electron microscope image is the boundary of the HSC and gap region, named HSC + gap. b Current density-voltage (J-V) curves of our HBC solar cell have efficiencies of 26.74% and 27.09% for total area (ta) and designated illumination area (da), respectively. These measurements were performed at ISFH under standard test conditions. c Electrical loss (VOC × FF loss) analysis of the three high-efficiency solar cells. Wherein the electrical loss is mainly represented by the recombination current density (J0 with the ideality factor of 1 and 2) and the series resistance (RS). The extracted values and equivalent circuits are described in Fig. S2. Detailed information on the recombination model has been reported in our previous work11. The black dotted lines in the figure are the isometric contour, as demonstrated in Fig. S4. The magnitude of the triangular area enclosed by the three parameters indicates the strength of the solar cell electrical performance. Specifically, smaller area implies lower electrical loss, which benefits the photoelectric performance of the solar cell. d Short-circuit current density loss (JSC loss) analysis of the three high-efficiency solar cells. The JSC loss are mainly represented by the shading effect (Jshade, including loss cuased by electrode shading and electrical shading) and the optical evaluation on the front and rear sides (Jfront and Jrear). The specific parameter values of the three solar cells are analyzed from respective external quantum efficiency (EQE) and reflection curves, as described in Fig. S5. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We employ a simplified recombination model11, outlined in Fig. S2, along with proper methodology and procedure, to extract the key electrical parameters of this solar cell. As depicted in Fig. 1c, the model yields the recombination current density (including the ideality factor of 1 and 2, i.e., J01 and J02) and the series resistance (RS). Both J01 and J02 are crucial in determining the electrical performance of c-Si solar cells. The calculated J01, ~1.1 fA·cm−2, benefits from sophisticated i-a-Si:H multilayer process, advanced interfacial engineering, and laser ablation technology, resulting in a high VOC of 745 mV (Table 1). The passivation advantage from Cell III, where an extremely high VOC of 751 mV was reported on a thin silicon wafer of 130 µm, is well demonstrated10. Considering the significant influence of silicon wafer thickness on VOC12,37, our HBC solar cell has exhibited one of the highest VOC values. In comparison to FBC configuration, the interdigitated pattern of HBC solar cells leads to orders of magnitude longer polarity boundary, potentially inducing severe boundary recombination loss (recombination parameter J02). The overlapping of conductive doped films or the residual of transparent conductive oxide (TCO) layer at the boundaries can both generate J02 and severely degrade the solar cell performance30,38,39. Through appropriate built-in electrical field governing and polarity boundary controlling, we achieved a J02 down to 0.6 nA·cm−2, enabling a pseudo fill factor (pFF) of up to 86.9% (Table 1), which is derived from the Suns-VOC measurement in Fig. S3. Regarding resistive loss, Fig. 1c shows that the RS of our HBC solar cell is around 0.34 Ω·cm2, which has not yet been optimized to the desired level compared to Cell II (~0.22 Ω·cm2) and Cell III (~0.20 Ω·cm2). This is consistent with the analysis of pseudo I–V curve (extracted from Suns-VOC measurement) and I–V curve at the maximum power point (MPP) (Fig. S3). Notably, Cell III employed nanocrystalline-doped films as transporting layers, while our HBC solar cells relied solely on amorphous silicon layers. This endows advantages including low leakage (at the area near the n-p polarity boundary), low cost, low deposition difficulty, and high uniformity. The relationship between the three main parameters in Fig. 1c and the normalized electrical performance is detailed in Fig. S4.

In addition to electrical analysis, the loss channels in JSC must be investigated, as shown in Fig. S5. Figure 1d reveals that the current density loss is tuned to an extremely superior condition on both the front and rear sides, together being lower than Cell III by 0.41 mA·cm−2. This indicates that the reflection and parasitic absorption of the front film layers and free-carrier absorption of the rear TCO layer largely satisfy the stringent requirements for highly efficient HBC solar cells. The all-back-contact structure inherently avoids electrode shading on the front side. However, the HBC solar cell is susceptible to electrical shading effects, as carriers for both polarities are collected on the same side. In this work, electrical shading induces a current density loss of 0.50 mA·cm−2, which is 0.25 mA·cm−2 lower than the electrode shading of Cell III, as shown in Fig. 1d. It is noteworthy that Cell I (da) and Cell II (da) obtained higher JSC values of 42.6 mA·cm−2 and 42.5 mA·cm−2, respectively. This is primarily attributed to the additional current gain from the thicker silicon wafer (175 µm and 200 µm) and the designated illumination area used in measurements, excluding the influences of recombination and leakage at the silicon wafer edge.

Recombination correlating to ideality factors

Due to the back-contact structural design, HBC solar cells introduce extra challenges regarding carrier recombination, particularly the parameter J02. Quantitatively evaluating J02 from various regions (HSC, ESC, gap, HSC + gap, as shown in Fig. 1a) of solar cells is challenging due to the submillimeter pitches. To address this, a group of indirect characterization techniques were developed (Fig. S6). First of all, a monitoring wafer (shown in Fig. 2a) was incorporated into the fabrication process. This wafer was laser-patterned into four regions (HSC, ESC, gap, HSC + gap) and underwent the same procedure as normal solar cells. J02 information was then extracted from the effective lifetime of each region. Experiment (exp) and fitted (fit) lifetime curves of each region are shown in Fig. 2b with the separated measurements detailed in Fig. S6a and the fitting model (Fig. S7a) explained in the “Methods”. Effective lifetimes of ESC and gap are close to 5000 μs under an injection level of 5 × 1015 cm−3, while those of HSC and HSC + gap are much lower, indicating better surface passivation in the former two regions. Consequently, J02 values in Fig. 2c of HSC and HSC + gap are much higher than those of ESC and gap, rendering J02 recombination from ESC and gap negligible in our normal cells. Notably, HSC + gap comprises HSC, gap, and their polarity boundary, as depicted in Fig. 1a. J02 of HSC + gap is 3.20 nA·cm−2, nearly 6 times higher than that of the HSC region alone and several orders of magnitude higher than that from the pure gap region, underscoring the significant issue of polarity boundary-related J02 recombination in HBC solar cells.

a Lifetime measurement of each region. b Experiment (exp) and fitted (fit) lifetime curves of each region. c The values of J02 extracted by fitting lifetime curves. d The sketch of dark I-V measurement by four-probe method. e Measured dark I-V curves of batch 1, 2, and pure gap samples. Batch 1 and 2 represent the samples soaked in alkaline solution without and with additive in step 4 of fabrication process flow (shown in Fig. S1), respectively. f Linear fitting of J02 and the ratio of perimeter to area. One anomalous point of batch 2 has been got rid of. g The impact of J01 and J02 on the value of (VOC × pFF)/(VOC,SQ × pFFSQ). h Left panel: the local sketch of the solar cell, showing the surface, junction, and bulk regions. A1 to A2, B1 to B2, C1 to C2, and D1 to D2 correspond to HSC, polarity boundary, gap, and ESC, respectively. Right panel: the energy band (left), total recombination rates (middle, U) and ideality factors (right, m) on the c-Si surface, in the junctions (p/n and n/n+) and in the bulk, as shown in each group of graphs. The information (energy band, U and m) suggested here is only from c-Si, not including other layers. And the injection level is 3 × 1015 cm−3, which is very close to the implied voltage at MPP. From the left to the right, the groups of graphs describe the case of HSC, polarity boundary, and ESC (or gap), respectively. Gap is recognized to hold the same case as ESC. EC, EV, and EF represent the bottom of conduction band, the top of valence band and Fermi level at equilibrium, respectively. The Y axis has the meaning of the depth in the c-Si bulk away from the surface (unit of length). 0 to 0.001, 0.001 to 3, and 3 to 5 represent the surface, the junctions, and the bulk of cells, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Gap region plays a negligible role in recombination loss of our device, which seems a contrary situation with the gap in tunneling oxide back contact (TBC) solar cells by Hollemann et al.40. In the reference work, due to the dopant inter-diffusion under high temperature, the larger and smaller widths of gap (dgap) exacerbate the recombination at the i-poly-Si/SiOx/c-Si interface and through lateral p(i)n diodes, respectively40. In other words, dgap has an optimum value to achieve the lowest gap recombination loss. The root reason for the different roles is the disparate gap structure designs. The gap layer stack we fabricated is SiNx/n-a-Si:H/i-a-Si:H/c-Si as shown in Fig. S1, while the structure in the reference is i-poly-Si/SiOx/c-Si. On the one hand, the passivation enhancement by dopant inter-diffusion is redundant for i-a-Si:H because the pretty good passivation quality could be provided by itself41. On the other hand, the lateral conductivity of doped amorphous silicon is much lower than that of doped crystalline silicon10. Such characteristic natively suppresses the leakage current from one polarity to the other. Therefore, the stack of SiNx/n-a-Si:H/i-a-Si:H/c-Si avoids to make balance between interface recombination and polarity leakage and could passivate the surface efficiently.

To further evaluate polarity boundary recombination, a specialized wafer was fabricated alongside normal cells (Fig. 2d). The front surface comprises HSC, gap, and their polarity boundary, while the entire rear surface is occupied by ESC. Nine sub-patterns and gap-only patterns were separately laid out on one wafer (Fig. S6b) with detailed description in the “Methods”. The current density of the gap sample is several orders of magnitude lower than that of samples from batch 1 and 2 (Fig. 2e), indicating negligible recombination current through the gap region compared to that caused by HSC and polarity boundary. Batch 1 and 2 represent the samples soaked in alkaline solution without and with additive in step 4 of fabrication process flow (shown in Fig. S1), respectively. Concerning the same ratio of perimeter to area, recombination current density of solar cells from batch 1 is higher than that from batch 2 (Fig. 2e), suggesting severer recombination loss in batch 1. Notably, the recombination loss extracted from dark I-V originates from three regions: gap (negligible), HSC, and the polarity boundary between HSC and gap, as shown in Fig. S7b. All of the dark I-V curves are depicted in Fig. S8 And with the purpose of distinguishing the polarity boundary recombination, the dark I-V data need to be further processed. For the nine sub-patterns (left in Fig. S6b), the J02 recombination values could be extracted by fitting these dark I-V curves, with the fitting model described in the “Methods”. Furthermore, the loss can be divided separately by linear fitting J02 and perimeter/area (Fig. 2f), the physical meanings of the slope and the intercept are suggested in the “Methods”. The slope of batch 1 is higher than that of batch 2, indicating the relatively lower polarity boundary recombination in the latter. The microstructure of the polarity boundary between HSC and gap is revealed in the transmission electron microscopy image of Fig. 1a. The polarity boundary of gap forms a concavity, where the subsequent TCO material burrows into during physical vapor deposition (PVD). Such a non-ideal polarity boundary, caused by wet etching, may induce detrimental boundary recombination. The additive directly influences the etching procedure of the boundary in step 4 of the process flow. Thus the J02 coming from polarity boundary could be reduced by adding additive into the solution. Regulating the morphology of polarity boundary is an effective approach to improving the performances of HBC solar cells.

Figure 2g demonstrates that increasing J01 and J02 results in a notable decrease in VOC and pFF. Through structural optimization and fabrication process improvements, J01 and J02 in our solar cells have been reduced to around 1.1 fA·cm−2 and 0.6 nA·cm−2, respectively. The ratio of (VOC × pFF)/(VOC,SQ × pFFSQ) exceeds 0.85, indicating the improved electrical performance. In the junction region of HSC, equilibrium-carrier concentrations (electron and hole) are much lower due to expulsion from the depletion region (Fig. S9). Here, a gradual change of carrier concentrations is assumed to depict the regions of HSC, polarity boundary, and ESC (gap), as shown in Fig. S9. In fact, the microstructure of the polarity boundary is much complicated and unclear although we have the transmission electron microscopy image. Nevertheless, the concavity at the boundary is visible in the image. And we could legitimately infer that there are lots of defects and contaminants in this region. These features would weaken the near-surface band bending in the c-Si42. Therefore, in our calculation, a lower built-in electrical field than that of HSC is assumed to equivalently simulate the polarity boundary, as shown in Fig. S9. The Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) recombination lifetime for electron and hole (τn0 and τp0) in the c-Si bulk region are both set as 15 ms. The local sketch of cell showing the surface, the junctions and the bulk is displayed on the left of Fig. 2h. The surface is two-dimensional in the practical cell and we assume a very thin film to describe it here. The energy band diagrams of HSC, the polarity boundary and ESC (gap) are depicted in Fig. 2h (the left graph in each group). Recombination rates (U) and the ideality factors (m) under the injection level of 3 × 1015 cm−3 are also calculated and shown in Fig. 2h (the middle and the right graphs in each group, respectively). In the HSC region, from A1 to A2, the ideality factor on the surface is higher than 1 because of the surface recombination in the p/n built-in electrical field. Besides, the SRH recombination makes the ideality factor in the p/n junction exceed 1 (Fig. S10) due to the low carrier concentration in this region (Fig. S9). And in the bulk, the dominant Auger recombination diminishes the ideality factor to below 1. Therefore, the J02 recombination of HSC comes from its surface and junction. As for polarity boundary, from B1 to B2, the J02 recombination is caused by the surface and junction just like HSC. And the lower built-in electrical field makes the ideality factor on the surface very close to 2. And the recombination rate increases at the same time. Consequently, the J02 recombination caused by the polarity boundary is violent. In terms of ESC (gap), from D1 to D2 (from C1 to C2), the ideality factor is no longer higher than 1, no matter on the surface, in the junction or in the bulk. That’s why the J02 recombination from these two regions could be ignored. In short, the J02 recombination of the cell is from two regions, HSC (surface and junction) and polarity boundary. And the former could be suppressed by enhancing the built-in electrical field and the latter could be reduced by managing the morphology of the boundary.

Contacts evaluation and design

According to the Suns-VOC and the light I-V tests, the total RS loss at MPP is around 337.2 mΩ·cm2, which can be disaggregated into four components: the resistive loss from HSC stacks (n-c-Si/i-a-Si:H/p-a-Si:H/TCO/Ag), the resistive loss from ESC stacks (n-c-Si/i-a-Si:H/n-a-Si:H/TCO/Ag), the metal resistive loss (fingers to busbars) and other loss sources (such as bulk resistance), as illustrated in Fig. 3a, b.

a, b Composition of series resistance (RS). c Contact resistivity (ρc) in comparison with reference work46. d Carrier transport optimization for HSC. e The simulated RS map for HBC solar cells (dashed lines) and FBC solar cells (colored blocks) with respect to ESC region ρc and HSC region ρc without consideration of metal resistive loss. f Design rules for the coverage area ratio of HSC and ESC region. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The transfer length method (TLM)43,44 was employed to extract the contact resistivity (ρc) of HSC based on p-a-Si:H using p-c-Si substrate and the ρc of ESC based on n-a-Si:H using n-c-Si substrate, as shown in Fig. S11a, b, respectively. The colored lines in Fig. S11a, b represent the dark I–V curves of two electrodes with different inter-electrode gap spacing. The insets in Fig. S11a, b plot the extracted resistance against the inter-electrode gap spacing. From the linear fit, we extracted a contact resistivity of 51.3 mΩ·cm2 for HSC and 46.1 mΩ·cm2 for ESC. The resistive loss from HSC stacks is calculated by RHSC = ρc(HSC)/AHSC, where AHSC represents the HSC contact area. The resistive loss from ESC stacks is calculated similarly.

At MPP, the predominant RS stems from HSC and ESC, primarily due to the high contact resistivity associated with the doped a-Si:H layers. The RS loss can be reduced by introducing doped nc-Si(Ox):H layers. With the current structural design, the transition from using doped a-Si:H material to nc-Si(Ox):H can improve FF of the device, while in the local area where HSC and ESC are in contact, the risk of current leakage increases as a result of facilitated tunneling transport through the HSC/ESC interface since a lower Ea enabled by the doped layers45. Notably, compared to devices employing doped a-Si:H layers, our approach demonstrates a substantial enhancement in the contact resistivity of the HSC region10. Further analysis of the resistive loss in the ESC and HSC regions reveals improvements in the contact resistivity near TCO and substrate interfaces. These enhancements are attributed to optimized intrinsic (i-a-Si:H) and doped (p-a-Si:H) amorphous silicon layers, which decrease the contact resistivity within the n-c-Si/i-a-Si:H/p-a-Si:H and p-a-Si:H/TCO stacks46, as shown in Fig. 3c. Specifically, the microstructure parameter tests indicate a narrowed bandgap in the i-a-Si:H layer near the p-a-Si:H/i-a-Si:H interface as depicted in Fig. S11c, easing direct tunneling at this interface21. Moreover, the lower activation energy observed in the p-a-Si:H layer adjacent to the p-a-Si:H/TCO interface facilitates carrier tunnel through p-a-Si/TCO interface, as illustrated in Fig. S11d. This optimization is further elucidated through comparative schematic band diagrams in Fig. 3d.

Figure 3e displays simulated RS map for typical HBC and FBC solar cells concerning ρc in the HSC and ESC region, excluding metal resistive loss. The range of color bars suggests a higher change ratio of RS against ρc(HSC) and ρc(ESC) in HBC compared to FBC solar cells, indicating the greater influence of ρc on HBC solar cell performance. Thus, meticulous design and fine-tuning of the HSC and ESC coverage area ratio are crucial. Unlike FBC solar cells where HSC and ESC cover the entire front or rear surface, their coverage area in HBC solar cells is adjustable, impacting total RS of the device. The design principle aims to minimize the resistive loss from HSC and ESC, contingent upon the ratio of ρc(HSC) and ρc(ESC). As shown in Fig. 3f, the optimal coverage area ratio can be calculated by the following equation:

Where X = ρc(HSC)/ρc(ESC) is the ratio of HSC region contact resistivity and ESC region contact resistivity, Y = AESC/AHSC+ESC is the optimal ratio of ESC coverage area to the total area. Moreover, minimizing the gap region area is imperative without compromising on increasing current leakage.

Examination and analysis of current loss

Figure 4a presents the external quantum efficiency (EQE) spectrum of our HBC solar cell, exhibiting two EQE curves measured with the total area (ta, M6 size) and designated illumination area (da, M2 size). The enhancement of EQE measured with da compared to ta across all wavelengths is nearly spectrum-independent, indicating the JSC loss is not from the optical channel but from recombination. Typically, recombination-induced JSC loss (Jrec) evenly impacts EQE across all wavelengths, akin to electrode shading, termed electrical shade loss (Jshade). Moreover, a detailed optical loss analysis using SunSolve software (as depicted in Fig. S12) revealed that JSC loss from front reflection and parasitic absorption of front layers (i-a-Si:H/SiNx) primarily affects EQE below 950 nm wavelength (Jfront), while the parasitic absorption of rear layers (i-a-Si:H/p-a-Si:H/TCO and i-a-Si:H/n-a-Si:H/TCO stacks) and escape reflection predominantly affect EQE beyond 950 nm wavelength (Jrear). The inset in Fig. 4a illustrates the HBC solar cell structure and the three main current density losses mentioned above. Concerning Jshade, it possibly arises from minority carriers (holes) recombination in the non-collection regions (ESC and gap region), due to their longer transport length (L2) to reach the collection region (HSC interface). This recombination current density loss is evidently wavelength-independent.

a External quantum efficiency (EQE) spectrum with two different test area. Inset shows the schematic diagram of the current density loss channels in HBC cell from the optics (Jfront and Jrear) and recombination (Jshade). Where the minority carrier (holes) upon ESC region has longer transport length (L2), compared to those upon HSC region (L1), to the collection region (i.e., HSC). Thus, recombination will be easier occurred in the path, leading to current density loss (electrical shade loss). b The demonstration of electrical shading phenomenon by simulation using Quokka software. It shows a smallest unit of the device (like the inset of Fig. 4a), where semi-transparent red color and semi-transparent blue color represent the HSC region and non-collection region (i.e., gap and ESC region), respectively. The upper panel is the internal quantum efficiency (IQE) as a function of device length under different surface recombination of gap and ESC region (SESC, gap), and bottom panel is the spatial map of current flow in device under 1 sun illumination for the case of SESC, gap = 64 cm·s−1. Where the colored arrows in bottom panel represent the hole current density with intensity (Jhole). c The measurement of light beam induced current (LBIC) at the wafer edge portion of our HBC solar cell with three different positions (marked as edge 1, edge 2, and edge 3). The upper panel shows the photography of rear surface of solar cell corresponding to the test area, while the middle panel is the amplification information corresponding to the dashed box in bottom panel. d The recombination current density (Jrec) as functions of effective lifetime (τeff) and transport length. Insert is the diagram of simulated structure. The τbulk and Jgen represent the silicon bulk lifetime and photo-generated current density. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Figure 4b shows the corresponding simulation results by Quokka 3 software. The upper panel simulates light beam induced current (LBIC, 20 µm width, 1 sun intensity, scanning from left to right in the X direction), which can be represented by the internal quantum efficiency (IQE, i.e., JSC/Jgen, where Jgen is the photogeneration current in silicon wafer). Notably, IQE at the HSC region (transparent red color) nearly reaches 100% as minority carriers above the HSC region are closer to the collection region. Conversely, minority carriers at the ESC and gap region (transparent blue color) exhibit a longer transport length before collection, resulting in lower IQE compared to the HSC region. IQE curve in this region further diminishes with increasing surface recombination of the ESC and gap region (SESC, gap), i.e. from 98% of SESC, gap = 1 cm·s−1 to ~90% of SESC, gap = 64 cm·s−1. To elucidate intermediate recombination, we depict the current distribution corresponding to SESC, gap = 64 cm·s−1 under 1 sun intensity (with full-area illumination) in the bottom panel. The HSC region shows one-dimensional current flow from the front surface to the rear side, whereas the ESC region displays two branches of the current flow: one perpendicular to the rear side and the other horizontal to the HSC interface, resulting in very high current density at the edge of the HSC region. More importantly, the direction of the current at the interface of ESC/n-c-Si is not parallel to the ESC surface, contrasting sharply with SESC, gap = 1 cm·s−1 conditions (Fig. S13), suggesting a portion of the current directly flows to the interface of ESC/n-c-Si for recombination.

Based on the lifetime test results of the ESC and gap regions in Fig. 2b, it is determined that the corresponding SESC, gap should be less than 3 cm·s−1, resulting in a total Jrec (the integral from 0 to 390 in the X axis) of less than 0.1 mA·cm−2. This value is significantly smaller than the estimated Jshade from Fig. 1d. Further examination of wafer edge using the light beam induced current (LBIC) method reveals in Fig. 4c, where the LBIC intensity uniformly decreases from ~2.8 mA (maximum value) at the left edge of the nearest HSC region to 0 at the edge of the solar cell. This wafer edge region is estimated to contribute approximately half of the JSC compared to the main part of the solar cell. Assuming an averaged span distance of 0.75~0.85 mm, the calculated Jshade from wafer edge region in M6 size wafer reaches (4 × (0.075~0.085) cm) × 16.6 cm × 21 mA·cm−2/274.4 cm2 = (0.38~0.43) mA·cm−2. Additionally, the magnified view of the LBIC scan indicates a current density difference of roughly 0.5 mA·cm−2 between the peaks and troughs of the ESC and HSC regions, nearly consistent with the simulated scenario of SESC, gap = 4 cm·s−1 in Fig. 4b. Thus their overall contribution to current density loss from SESC, gap is about 0.1 mA·cm−2, accounting for ~20% of the total Jshade (~0.5 mA·cm−2). Simulation results suggest that wafer edge recombination-induced current density loss can be controlled to below 0.1 mA·cm−2 (Fig. S14) with effective wafer edge passivation.

In HBC solar cells, electrical shading is primarily influenced by the ESC or gap region, recombination at the front surface, and the quality of the silicon wafer. Recombination in the HSC region has a lesser important impact on JSC (Fig. S15). Jrec is mainly determined by carrier transport length and recombination rate. Figure 4d shows a calculation of Jrec as a function of carrier transport length (Ltr) and equivalent effective minority lifetime (τeff). The inset model illustrates the transport of photo-generated carriers (Jgen) from the right to the left of the device, where they are collected effectively (JSC) or undergo recombination on the path (Jrec) with different τeff and Ltr. For convenience, τeff is equivalent to τbulk under perfect surface passivation (i.e., J0 surf = 0.001 fA·cm−2), with the bulk lifetime set to a fixed value. A simple equation can be derived from the transport equation and the boundary condition:

Where Lp = (Dp × τeff)1/2 is the diffusion length of hole carrier, and Dp ≈ 11.9 cm2·s−1 is the diffusion coefficient of the hole carrier. As depicted in Fig. 4d, the results obtained from Quokka 3 simulations (hollow circles) closely alight with these calculated by Eq. (2) (solid lines). Consequently, Eq. (2) or Fig. 4d can be employed to quickly evaluate Jrec across various cell structures, spatial positions, and applied voltages. Notably, in HBC solar cells, the lateral width of the ESC region is significantly larger compared to the carrier transport length (up to the thickness of the silicon wafer) of the traditional FBC solar cells, increasing the likelihood of substantial electrical shading if τeff in this region is suboptimal. For example, at X = 390 µm in Fig. 4b, with Ltr = ~270 µm (from the front surface at X = 390 µm to the edge of collection region), and τeff = ~0.26 ms for SESC, gap = 64 cm·s−1, IQE can be quickly calculated as IQE = (1-Jrec/Jgen) = (1/cosh(L/Lp)) = 89.2%. In another scenario, despite negligible surface recombination, if the silicon wafer quality is low (e.g., τbulk = 1 ms), Jrec in the middle of the ESC (X = 390 µm in Fig. 4b) can increase from ~0.1 mA·cm−2 (for τbulk = 16 ms) to 1.2 mA·cm−2.

Opportunities and perspectives

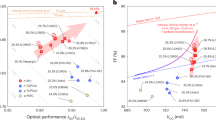

Analysis of the HBC solar cell reveals significant potential for improving its photoelectric performance. Compared to nanocrystalline silicon, amorphous silicon has not effectively suppressed charge carrier transport loss due to inefficient transport at the interface between the doped layer and the TCO layer (Fig. 5a), not fulfilling band-to-band tunneling mechanism based on direct energy transitions. To enhance efficiency, adopting nanocrystalline silicon technology for improving contact properties is recommended. Using nanocrystalline silicon for both HSC and ESC stacks without oxygen alloy doping achieves low contact resistivity values of ρc(HSC) = 3.6 mΩ·cm2 and ρc(ESC) = 15 mΩ·cm2 10,47,48. Under the model illustrated in Fig. 3e, f and conjunction with the optimized rear structural design, the resistive loss can be minimized to <0.12 Ω·cm2, as shown in Cell IV of Table 2. Such decline of resistive loss would make FF increase from 85.08% to 86.22%. Consequently, the normalized electrical performance (VOC × FF)/(VOC,SQ × FFSQ) improves from 0.832 to 0.843, enhancing the absolute efficiency by 0.35%. Furthermore, integrating less resistive SiOx/poly-Si stacks with i-a-Si:H/doped-a-Si:H stacks forms hybrid solar cells with even better performance potential49,50,51,52. Based on Cell IV, it is prospective to decrease the recombination parameters J01 and J02 to the same level of Cell III by fully reinforcing the combined effects such as field-effect passivation and polarity boundary passivation, just as shown as Cell V in Table 2. On the one hand, in consideration of the main electrical difference between amorphous silicon and nanocrystalline silicon, enhancing the built-in electric field in the p/n junction is one of the most promising methods to suppress J01 and J02 (as shown in Fig. 2h). On the other hand, HBC cells usually have extra recombination loss from their non-ideal polarity boundary as shown in Figs. 1a and 2b. Thus boundary management is another promising method to reduce J01 and J02. If these methods are felicitously utilized on the HBC cell, its VOC and FF would increase to 746.5 mV and 86.54%, respectively. And, thus the parameter (VOC × FF)/(VOC,SQ × FFSQ) can be optimized to 0.847, as depicted in Fig. 5a.

a Electrical performance of solar cells as a function of parameters (J01, J02, and RS) normalized by SQ limit of c-Si solar cells under standard test conditions. b Optical performance of solar cells as a function of parameters (Jfront, Jrear, and Jshade). Detailed information can be found in Table 2, Figs. 1c, d, and S3–S5. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

However, JSC of the HBC solar cell with a total area in this work is only 42.1 mA·cm−2, ~0.4 mA·cm−2 lower than Cell II, due to the electrical shading effect in the ESC region and wafer edge recombination effects. Excluding the wafer edge region, the same HBC solar cell with a designated area of ~243 cm2 can achieve a JSC of up to 42.6 mA·cm−2. The issue of wafer edge recombination loss can be well addressed by improving film uniformity, avoiding wrap-around coatings, and implementing secondary passivation on wafer edge (such as atomic-layer-deposited AlOx thin films or spin-coated organic passivation layers of PEDOT:PSS and carbon nanotube)53,54,55,56,57. Meanwhile, coupled with an optimized rear structure design enables suppress the electrical shading loss Jshade from 0.50 mA·cm−2 down to below 0.1 mA·cm−2, as described in Cell IV in Fig. 5b and Table 2. In other words, the JSC could be increased to 42.5 mA·cm−2 by suppressing the electrical shading effect. And Jrear decreasing from 0.69 mA·cm−2 to 0.59 mA·cm−2 by preventing the free-carrier parasitic absorption of TCO brings additional increase of 0.1 mA·cm−2 for JSC. Moreover, meticulous optimization of the front anti-reflection coating and rear reflector is crucial. For instance, replacing the front layer (i-a-Si:H/SiNx) with AlOx/SiNx or SiOx/SiNx stacks and preparing silver mirror or other rear reflection enhancement layers will improve spectrum management capabilities58, reducing the Jfront from 0.59 mA·cm−2 to 0.35 mA·cm−2 and leading to a promising JSC of 42.8 mA·cm−2, i.e., Cell V in Table 2. Leveraging this high-efficiency HBC solar cell as a benchmark demonstrates its advantages over FBC solar cells. As mentioned above, both the normalized electrical performance of 0.847 and the JSC of 42.8 mA·cm−2 are feasible. It suggests that a conversion efficiency of up to 27.7% is achievable with optimal practices, i.e., Cell V in Table 2.

Discussion

Through extensive research and analysis of the core optimization direction in the preparation process of HBC solar cells, we have achieved a high PCE of 27.09%. Two crucial aspects and their corresponding six parameters for efficient HBC solar cells have been identified. By comparing these parameters with two previous record silicon solar cells, we observed the suppression of surface recombination of J01 and J02 in this HBC solar cell compared to Keneka’s HBC solar cell, along with significant advantages in Jshade and Jfront compared to our previous FBC (SHJ) solar cell.

In our investigation of J01 and J02, we utilized zone-resolved minority carrier lifetime testing and variations of polarity boundary perimeter I-V curves to precisely define the J02 source region. Our findings indicate that J02 in HBC solar cells primarily originates from the HSC region and the polarity boundary of HSC/gap region. Through optimization, we have successfully reduced the J02 down to ~0.6 nA·cm−2 (compared to Kaneka’s J02~1.3 nA·cm−2). Additionally, by analyzing the ideality factor profile corresponding to each recombination region, we have identified insufficient band bending in the HSC region and the boundary of HSC/gap region as the primary causes of J02.

In our examination of RS, we found that contact resistivity plays a pivotal role in high-efficiency HBC solar cells, mainly due to a significant reduction in the contact area of the HSC or ESC region. By optimizing the HSC region, we achieved the lowest contact resistivity (<55 mΩ·cm2) using p-a-Si:H film. Furthermore, we determined that the contribution of contact resistivity to RS can be directly calculated based on the coverage area ratio. Optimal RS is achieved by maintaining an inverse proportion between the HSC and ESC coverage area ratio and their corresponding contact resistivity.

In terms of JSC loss, we conducted a detailed breakdown and quantification of Jfront, Jrear, and Jshade using EQE and reflection curve analyses. Simulations and LBIC tests have shown that minority carriers in the ESC and gap regions of HBC solar cells experience higher rates of recombination due to their longer transport lengths, resulting in an electrical shading effect. Additionally, significant recombination at the wafer edge region of the solar cell competes with the HSC region near the wafer edge for minority carriers, resulting in ~50% of JSC loss. This phenomenon accounts for over 80% of electrical shading in our HBC solar cell during full-area testing. Furthermore, we have developed a simplified equation to elucidate the relationship between Jrec, Ltr, and τeff, enabling quick assessments of the extent of electrical shading.

Finally, we have presented the two key aspects in three-dimensional graphs, showcasing the optimization space for both electrical and optical designs. By incorporating the nanocrystalline technology from the 26.81% efficiency solar cell, addressing wafer edge effects while maintaining other parameters, and meticulous optimization of front anti-reflection coating and rear reflector, it is practical to achieve an HBC solar cell with PCE surpassing 27.7%.

Methods

Device fabrication

Solar cell fabrication

In this work, solar cells were fabricated using the commercial HBC research and development line on LONGi M6 (274.3 cm2) n-type Czochralski wafer with a resistivity of 1.2–1.5 Ω·cm and a thickness of 200 µm in (100) orientation. The main steps for HBC solar cell fabrication using the laser patterning technique are shown in Fig. S1, involving multi-step wet chemical cleaning, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), laser ablation, PVD, and metallization process. (1) Wet chemical cleaning - 1: the rear surface was polished through isotropic etching, while the front wafer surface was textured via anisotropic etching into pyramids sized 1−3 µm, featuring (111) oriented facets. Prior to subsequent deposition, the thickness of the wafer was verified by weight measurement, confirming it to be ~175 µm. (2) CVD deposition - 1: after a brief dip in a diluted hydrofluoric solution, the rear side passivation was achieved using i-a-Si:H/n-a-Si:H/SiNx/i-a-Si:H stack, where the SiNx/i-a-Si:H stack was used as a laser sacrificial layer or an etch stop layer in the subsequent process. (3) Laser patterning - 1: a pulsed green picosecond laser (100 kHz, 532 nm, ps) was employed to ablate the outermost sacrificial layer (i-a-Si:H) of the HSC region. (4) Wet chemical cleaning - 2: the SiNx layer was acid-etched (HF), and the n-a-Si:H/i-a-Si:H stack was alkaline-etched (KOH), which ensures the n-c-Si is undamaged and retains a clean surface for subsequent CVD process. (5) CVD deposition - 2: The i-a-Si:H/p-a-Si:H stack was deposited on the rear side and formed a good passivating contact performance in the HSC region. (6) Laser patterning - 2: a pulsed green picosecond laser (100 kHz, 532 nm, ps) was applied to ablate the overlying i-a-Si:H/p-a-Si:H stack in the designed ESC region. (7) Wet chemical cleaning - 3: the SiNx layer and laser-induced oxidation layer were etched by HF acid to forms the surface of n-c-Si/i-a-Si:H/n-a-Si:H. (8) CVD deposition - 3: the front side was coated with i-a-Si:H/SiNx/SiOx stack, which serves as both passivation layer and anti-reflection coating. (9) PVD deposition: the TCO layer was deposited using the magnetron sputtering technique. The TCO layer consisted of conventional 10 wt% SnO2 doped In2O3, and was prepared simultaneously for both the HSC and ESC regions using a single deposition recipe. (10) Laser patterning - 3: a pulsed ultra-violet picosecond laser (400 kHz, 355 nm, ps) ablated the designed gap region to remove TCO/p-a-Si:H/i-a-Si:H stack for isolation, avoiding leakage channels. And, the SiNx layer served as barrier layer to prevent the passivation performance of i-a-Si:H/n-a-Si:H from being damaged. (11) Metallization: silver grid electrodes were printed and subjected to a curing process at ~170 °C in an annealing furnace. Finally, light soaking was performed under 30 suns for 90 s at 200 °C.

Lifetime monitoring sample fabrication

The lifetime monitoring sample was fabricated on a M6 Czochralski n-c-Si wafer with the same bulk resistivity and wafer thickness as used in “Solar cell fabrication”. The monitoring sample underwent the same fabrication flow as the normal solar cell except for three processes. Firstly, the sample was processed according to the four-region pattern design (HSC, ESC, gap, HSC + gap) rather than the normal cell pattern at every laser step. Second, prior to the deposition of the TCO layer, the high-temperature tape was applied to the gaps between each region. This tape was removed after the PVD process to prevent carrier transportation between regions. Thirdly, the sample was not printed but subjected to annealing and light soaking along with the normal solar cells. The lifetime after light soaking was subsequently measured and analyzed.

Dark I–V monitoring sample fabrication

The dark I–V monitoring sample was also fabricated on the M6 Czochralski n-c-Si wafer with the same bulk resistivity and wafer thickness as used in “Solar cell fabrication”. One side of the wafer underwent the patterning process realized by laser technology. This side was divided into the periodic HSC and gap regions, as shown in Fig. 2d. The opposite side of the wafer was occupied entirely by the ESC region. After this, a TCO layer was deposited on both surfaces. Silver electrodes were then fabricated in the ESC region and the sub-patterns using a mask plate.

Performance characterization

The light I-V curves of the HBC solar cell with the total area and designated illumination area were tested and certified by ISFH. The measurements of EQE (ta and da) curves in Fig. 4a and the reflection curve in Fig. S5a were performed by our lab (test instrument: PVE300-IVT210). Whereas the current density loss involved in Figs. 1 and 5 were analyzed based on the EQE (ta) measurement by ISFH, which curve was shown in Fig. S5a. It is worth noting that the EQE (ta) measurement by our lab was calibrated and aligned with ISFH. The measured JSC in the light I-V measurement was consistent with the JSC calculated from the spectral response measurement. The EQE curve was derived by integrating the spectral response curve. The pseudo I-V curve in Fig. S3 was measured on Sinton instrument (Suns-VOC MX). Notably, all these tests are performed on the same solar cell.

The lifetime was measured on Sinton instrument (WCT-120 MX) in transient mode. To obtain lifetime information for each region (HSC, ESC, gap, HSC + gap), each region was moved to the center of the stage to completely cover the sensor region, as illustrated in Fig. S6a. The dark I-V of the monitoring cells was tested using a semiconductor analyzer (Keithley 4200A-SCS). As shown in Fig. 2d, the probes contacted the electrodes of the front and rear sides. The voltage was swept from 0 V to 2 V in 0.01 V increment.

Contact resistivity was calculated using the TLM43,44. Microstructure parameters of i-a-Si:H layers were determined from the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy measurements by fitting peaks corresponding to Si-H bond and Si-H2 bonds and comparing their area shares59,60,61. Activation energies of doped-a-Si:H layers were determined from the electrical conductivity as a function of temperature, with electrical conductivities obtained from I-V curves measured by a semiconductor analyzer.

The LBIC measurement was performed using a 532 nm laser with a spot diameter of 20 µm.

Theoretical calculation and simulation

J 02 extracted from lifetime curves

A simplified recombination model was used to fit the lifetime curves, as shown in Fig. S7a. The effective lifetime τeff can be divided into five components, as expressed in Eq. (3). Unlike the model used in I-V curve fitting, this model does not consider series resistance RS and shunt resistance Rsh. The electron SRH recombination lifetime τn0 was set as 15 ms and equal to the hole SRH recombination lifetime τp0. Please note that,τn0 and τp0 are the physical quantities used to calculate effective bulk SRH lifetime (τSRH), corresponding to SRH electron lifetime and SRH hole lifetime, respectively. And τ01 and τ02 are used to describe the surface recombination, corresponding to J01 and J02 recombination, respectively. Bulk resistivity and wafer thickness were 1.5 Ω·cm and 175 µm, respectively.

J 02 extracted from dark I–V curves

As shown in Fig. S7b, dark I–V curves consist of three types of recombination: HSC (JHSC), gap (Jgap), and the boundary between the HSC and gap (Jbound.). These recombinations are mathematically correlated, as shown in Eq. (4). Jdark is the current density obtained by dividing the dark current Idark by the total area of the HSC (AHSC) and gap (Agap) regions. Lbound. is the length of the boundary between the HSC and gap. In Fig. 2f, the measured and fitted correlation between J02 and Lbound./(AHSC+Agap) is illustrated. The slope of this correlation reflects polarity boundary recombination (Jbound.), while the intercept provides information on the recombination in the HSC region (JHSC), as the recombination of the gap region is negligible.

The metal resistive loss calculation

Both HSC and ESC regions have m busbars and n fingers, respectively. The metal resistive loss is calculated by the following question:

Where, Rsf_e = (L × Rl)/4 is the effective resistance of a single finger in the edge, L is finger length between busbars and finger length in the edge is L/2, Rl is the finger resistance per length. \({R}_{{{{\rm{sf}}}}{{{\rm{\_}}}}{{{\rm{c}}}}}={\int }_{0}^{{R}_{{{{\rm{sf}}}}{{{\rm{\_}}}}{{{\rm{t}}}}}}\frac{1}{\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{{R}_{{{{\rm{sf}}}}{{{\rm{\_}}}}{{{\rm{t}}}}}-x}}{dx}\) is the effective resistance of a single finger between busbars, and Rsf_t = (Rl × L) is the total resistance of a single finger between busbars.

The Quokka 3 simulation

The unit cell was modeled in 3D to calculate the LBIC and spatial mapping of current flow, as shown in Fig. 4b. By default, the resistivity, thickness, and lifetime of the silicon wafer were set to 1.5 Ω·cm, 175 µm, and 15 ms, respectively. The default recombination current density was set to 0.5 fA·cm−2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article and its Supplementary Information and Source Data files. Source data are provided with this paper and are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26011138. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhong, Z. et al. Role of CO2 geological storage in China’s pledge to carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Energy 272, 127165 (2023).

Wei, Y.-M. et al. Policy and management of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality: a literature review. Engineering 14, 52–63 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Electric power supply structure transformation model of China for peaking carbon dioxide emissions and achieving carbon neutrality. Energy Rep. 8, 541–548 (2022).

Li, Z. Prospects of photovoltaic technology. Engineering 21, 28–31 (2023).

Allen, T. G., Bullock, J., Yang, X., Javey, A. & De Wolf, S. Passivating contacts for crystalline silicon solar cells. Nat. Energy 4, 914–928 (2019).

Glunz, S. W. et al. Silicon‐based passivating contacts: the TOPCon route. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 31, 341–359 (2021).

Kafle, B. et al. TOPCon – technology options for cost efficient industrial manufacturing. Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells 227, 111100 (2021).

Adachi, D., Hernández, J. L. & Yamamoto, K. Impact of carrier recombination on fill factor for large area heterojunction crystalline silicon solar cell with 25.1% efficiency. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 233506 (2015).

Haschke, J., Dupré, O., Boccard, M. & Ballif, C. Silicon heterojunction solar cells: recent technological development and practical aspects - from lab to industry. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 187, 140–153 (2018).

Lin, H. et al. Silicon heterojunction solar cells with up to 26.81% efficiency achieved by electrically optimized nanocrystalline-silicon hole contact layers. Nat. Energy 8, 789–799 (2023).

Lin, H. et al. Unveiling the mechanism of attaining high fill factor in silicon solar cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 1–13 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Flexible silicon solar cells with high power-to-weight ratios. Nature 626, 105–110 (2024).

Ru, X. et al. 25.11% efficiency silicon heterojunction solar cell with low deposition rate intrinsic amorphous silicon buffer layers. Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells 215, 110643 (2020).

Long, W. et al. On the limiting efficiency for silicon heterojunction solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 231,111291 (2021).

Shockley, W. & Queisser, H. J. Detailed balance limit of efficiency of p-n junction solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 32, 510–519 (1961).

Green, M. A. et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 64). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 32, 425–441 (2024).

Richter, A. et al. Design rules for high-efficiency both-sides-contacted silicon solar cells with balanced charge carrier transport and recombination losses. Nat. Energy 6, 429–438 (2021).

Richter, A. et al. n-Type Si solar cells with passivating electron contact: identifying sources for efficiency limitations by wafer thickness and resistivity variation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 173, 96–105 (2017).

Jeong, M. S. et al. Origin of screen-printed metal contact losses in crystalline silicon solar cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 6, 11983–11992 (2023).

Tepner, S. & Lorenz, A. Printing technologies for silicon solar cell metallization: a comprehensive review. Prog. Photovolt.: Res. Appl. 31, 557–590 (2023).

Luderer, C., Kurt, D., Moldovan, A., Hermle, M. & Bivour, M. Intrinsic layer modification in silicon heterojunctions: balancing transport and surface passivation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 238, 111412 (2022).

Tomasi, A. et al. Simple processing of back-contacted silicon heterojunction solar cells using selective-area crystalline growth. Nat. Energy 2, 17062 (2017).

Reichel, C., Granek, F., Hermle, M. & Glunz, S. W. Investigation of electrical shading effects in back-contacted back-junction silicon solar cells using the two-dimensional charge collection probability and the reciprocity theorem. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 024507 (2011).

Razzaq, A., Allen, T. G. & De Wolf, S. Design criteria for silicon solar cells with fill factors approaching the auger limit. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 4438–4440 (2023).

Yoshikawa, K. et al. Exceeding conversion efficiency of 26% by heterojunction interdigitated back contact solar cell with thin film Si technology. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 173, 37–42 (2017).

Yoshikawa, K. et al. Silicon heterojunction solar cell with interdigitated back contacts for a photoconversion efficiency over 26%. Nat. Energy 2, 17032 (2017).

Haase, F. et al. Interdigitated back contact solar cells with polycrystalline silicon on oxide passivating contacts for both polarities. Jpn. J. App. Phys. 56, 08MB15 (2017).

Haase, F. et al. Laser contact openings for local poly-Si-metal contacts enabling 26.1%-efficient POLO-IBC solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 186, 184–193 (2018).

Hollemann, C. et al. 26.1%‐efficient POLO‐IBC cells: quantification of electrical and optical loss mechanisms. Prog. Photovolt.: Res. Appl. 27, 950–958 (2019).

Lin, H. et al. Edge effect in silicon solar cells with dopant-free interdigitated back-contacts. Nano Energy 74, 104893 (2020).

Procel, P. et al. Opto-electrical modelling and optimization study of a novel IBC c-Si solar cell. Prog. Photovolt.: Res. Appl. 25, 452–469 (2017).

Spinelli, P., van de Loo, B. W. H., Vlooswijk, A. H. G., Kessels, W. M. M. & Cesar, I. Quantification of pn-junction recombination in interdigitated back-contact crystalline silicon solar cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 7, 1176–1183 (2017).

Yang, Z., Lin, H., Chee, K. W. A., Gao, P. & Ye, J. The role of front-surface charges in interdigitated back contact silicon heterojunction solar cells. Nano Energy 61, 221–227 (2019).

Zou, S. et al. A solid strategy to realize heteroface selective emitter and rear passivated silicon solar cells. Prog. Photovolt.: Res. Appl. 30, 1343–1353 (2022).

Schwab, C. et al. Recombination and optical properties of wet chemically polished thermal oxide passivated Si surfaces. IEEE J. Photovolt. 3, 613–620 (2013).

Green, M. et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 57). Prog. Photovolt.: Res. Appl. 29, 3–15 (2020).

Herasimenka, S. Y., Dauksher, W. J. & Bowden, S. G. 750 mV open circuit voltage measured on 50 μm thick silicon heterojunction solar cell. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, (2013).

Yu, C. et al. Silicon solar cell with undoped tin oxide transparent electrode. Nat. Energy 8, 1119–1125 (2023).

Kirner, S. et al. The influence of ITO dopant density on J-V characteristics of silicon heterojunction solar cells: experiments and simulations. Energy Procedia 77, 725–732 (2015).

Hollemann, C. et al. Separating the two polarities of the POLO contacts of an 26.1%-efficient IBC solar cell. Sci. Rep. 10, 658 (2020).

Cuevas, A. et al. Skin care for healthy silicon solar cells. In: 2015 IEEE 42nd Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), 1–6 (2015).

Shu, Z., Das, U., Allen, J., Birkmire, R. & Hegedus, S. Experimental and simulated analysis of front versus all-back-contact silicon heterojunction solar cells: effect of interface and doped a-Si:H layer defects. Prog. Photovolt.: Res. Appl. 23, 78–93 (2015).

Meier, D. L. & Schroder, D. K. Contact resistance: its measurement and relative importance to power loss in a solar cell. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices ED-31, 647–653 (1984).

Huang, K.-C., D. Janes, K. W. & Melloch, M. A transfer length model for contact resistance of two-layer systems with arbitrary interlayer coupling under the contacts. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 43, 676–684 (1996).

Calcabrini, A. et al. Low-breakdown-voltage solar cells for shading-tolerant photovoltaic modules. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 101155 (2022).

Luderer, C., Messmer, C., Hermle, M. & Bivour, M. Transport losses at the TCO/a-Si:H/c-Si heterojunction: influence of different layers and annealing. IEEE J. Photovolt. 10, 952–958 (2020).

Antognini, L. et al. Integration of thin n-type nc-Si:H layers in the window-multilayer stack of heterojunction solar cells. Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells 248, 111975 (2022).

Procel, P. et al. The role of heterointerfaces and subgap energy states on transport mechanisms in silicon heterojunction solar cells. Prog. Photovolt.: Res. Appl. 28, 935–945 (2020).

Yan, D., Cuevas, A., Wan, Y. & Bullock, J. Passivating contacts for silicon solar cells based on boron-diffused recrystallized amorphous silicon and thin dielectric interlayers. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 152, 73–79 (2016).

Yan, D., Cuevas, A., Bullock, J., Wan, Y. & Samundsett, C. Phosphorus-diffused polysilicon contacts for solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 142, 75–82 (2015).

Schmidt, J., Peibst, R. & Brendel, R. Surface passivation of crystalline silicon solar cells: present and future. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 187, 39–54 (2018).

Su, Q. et al. Theoretical limiting‐efficiency assessment on advanced crystalline silicon solar cells with Auger ideality factor and wafer thickness modifications. Prog. Photovolt. 32, 587–598 (2024).

Giglia, V., Varache, R., Veirman, J. & Fourmond, E. Influence of cell edges on the performance of silicon heterojunction solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 238, 111605 (2022).

Richter, A., Patel, H., Reichel, C., Benick, J. & Glunz, S. W. Improved silicon surface passivation by ALD Al2O3/SiO2 multilayers with in‐situ plasma treatments. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 10, 2202469 (2023).

Lin, H. et al. Realization of interdigitated back contact silicon solar cells by using dopant-free heterocontacts for both polarities. Nano Energy 50, 777–784 (2018).

Yan, J. et al. Stable organic passivated carbon nanotube–silicon solar cells with an efficiency of 22%. Adv. Sci. 8, e2102027 (2021).

Bai, Y. et al. Interdigitated back‐contacted carbon nanotube–silicon solar cells. Small Struct. 4, 432–437 (2023).

Hao, B. et al. Comparing single-, double- and triple-layer anti-reflection coatings for ultra-low reflectance in silicon heterojunction solar cells. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 62, 061002 (2023).

Brodsky, M. H., Cardona, M. & Cuomo, J. J. Infrared and Raman spectra of the silicon-hydrogen bonds in amorphous silicon prepared by glow discharge and sputtering. Phys. Rev. B 16, 3556–3571 (1977).

Smets, A. H. M., Kessels, W. M. M. & Sanden, M. C. M. v. d. Vacancies and voids in hydrogenated amorphous silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 1547–1549 (2003).

Mouro, J., Gualdino, A., Chu, V. & Conde, J. P. Microstructure factor and mechanical and electronic properties of hydrogenated amorphous and nanocrystalline silicon thin-films for microelectromechanical systems applications. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 184905 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2022YFB4200203, P.G.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62034009, 62104268, P.G. and H.L.). We thank Fei Luo, Tuan Yuan, Zhipeng Huang, Xiaoyu Deng, Po Fang, Qing Tang, Fan Yu, Yan Gao, Jiawei Li, Lei Xie, Haoran Qiu, and Mingzhe Yu for process optimization, sample preparation, cell fabrication, and characterizations; and all group members of LONGi Central R&D Institute for continuous support. Sun Yat-sen University and LONGi Green Energy Technology Co., Ltd have equal rights to this work. We also thank Qiming Liu of Lanzhou University for its transmission electron microscopy characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. and P.G. conceived the idea. H.W., C.X., L.F., J.L., and X.X. fabricated the HBC solar cell. G.W., Q.S., and H.L. designed the characterization experiments. G.W., Q.S., and T.W. performed the characterization and measurement. G.W., Q.S., H.T., H.L., C.H., and P.G. analyzed the data and explored the mechanisms. G.W., Q.S., H.T., and H.L. performed device simulations. H.W., C.X., L.F., J.L., X.X., and Z.L. contributed to the development of the HBC solar cell. G.W., Q.S., H.T., and H.L. co-wrote the manuscript. H.L., L.F., X.X., Z.L, and P.G. supervised the study. All authors participated in the discussions and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Su, Q., Tang, H. et al. 27.09%-efficiency silicon heterojunction back contact solar cell and going beyond. Nat Commun 15, 8931 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53275-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53275-5

This article is cited by

-

Dual-functional p-NiO@CuO/n-si heterostructures for MIS photodiodes under varying light intensities and photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine-B under visible light

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2026)

-

Recent Advancements and Perspectives of Low-Dimensional Halide Perovskites for Visual Perception and Optoelectronic Applications

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)

-

Stable δ-FA(Cs)PbI3 intermediate enables fabrication of large-area perovskite solar modules in ambient air

Science China Materials (2026)

-

Large scale and diverse two-dimensional flake segmentation dataset by general-purpose and labor-efficient annotation framework

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2025)

-

Efficiency improvement in silicon and perovskite solar cells through nanofluid cooling using citrate and PVP stabilized silver nanoparticles

Scientific Reports (2025)