Abstract

Making adaptive decisions requires predicting outcomes, and this in turn requires adapting to uncertain environments. This study explores computational challenges in distinguishing two types of noise influencing predictions: volatility and stochasticity. Volatility refers to diffusion noise in latent causes, requiring a higher learning rate, while stochasticity introduces moment-to-moment observation noise and reduces learning rate. Dissociating these effects is challenging as both increase the variance of observations. Previous research examined these factors mostly separately, but it remains unclear whether and how humans dissociate them when they are played off against one another. In two large-scale experiments, through a behavioral prediction task and computational modeling, we report evidence of humans dissociating volatility and stochasticity solely based on their observations. We observed contrasting effects of volatility and stochasticity on learning rates, consistent with statistical principles. These results are consistent with a computational model that estimates volatility and stochasticity by balancing their dueling effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is critical for organisms to infer the true cause of their noisy observations. Take, for example, hiking in the mountains and encountering an unexpected change in weather. It is important to distinguish between regular weather fluctuations, like a passing cloud, and significant weather events, such as an approaching thunderstorm. The appropriate response will depend on accurately assessing the cause of the weather change. The main challenge is that although in both scenarios, the weather is currently less predictable, they should have opposite effects on the hiker’s behavior. If the unexpected weather change is caused by regular fluctuations (referred to as “stochasticity”), the hiker needs to continue with their current course of action. However, if the weather change is caused by a thunderstorm (referred to as “volatility”), the hiker must quickly respond because earlier estimates of the situation quickly become irrelevant.

Significant progress has been made in the field of computational neuroscience regarding our understanding of how organisms learn and adapt in noisy environments. A notable achievement has been the development of models that link error-driven learning to principles of sound statistical inference1,2,3,4,5. This approach of recasting learning as statistical inference has inspired and grounded an influential research program studying neuropsychological systems supporting reinforcement learning and choice6,7,8,9,10.

Classically, error-driven learning relies on two key factors: prediction error, which is the difference between actual and expected outcomes, and the learning rate, which determines the weight assigned to new information. Importantly, the statistical re-interpretation of these rules provides a formal justification for the learning rate, revealing that rather than being an arbitrary free parameter, it should be influenced by the statistical properties of noise in the environment: specifically, both volatility and stochasticity. Higher volatility, indicating rapid environmental changes, reduces the usefulness of old information and requires a higher learning rate. Conversely, higher stochasticity should decrease the learning rate, because more stochastic outcomes provide less information about future outcomes. This perspective has fostered influential research programs focused on constructing hierarchical Bayesian models for learning, which describe how organisms could learn from observations while also inferring their volatility and/or stochasticity6,7,8,11,12. However, despite previous experimental studies demonstrating human adaptability to either volatility or stochasticity (typically manipulated and modeled in isolation from one another, or at least with the second variable changing only incidentally), a more challenging computational question remains unanswered: whether and how organisms infer the true cause of noise, some mixture of volatility or stochasticity, when both factors are unknown and potentially changing. This is challenging because although volatility and stochasticity require opposite adjustments to the learning rate, they are easy to confuse, because they each make observations more noisy, albeit by subtly different patterns.

While both factors have been individually recognized in the field for approximately two decades, the computational challenges that arise when both factors are simultaneously changing have been largely neglected until recently13. Volatility, in particular, is an extensively researched concept6,11,14,15, with numerous experiments documenting behavioral and neural markers that demonstrate how learning rate increases when volatility is increased6,8,10,12,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. These studies have also explored the disruption of these effects in relation to psychopathologies15,16,17,18,23,24,26,27,28. Many such studies have systematically manipulated volatility in blocks, with stochasticity changing only incidentally due to (and confounded by) changes in the mean of binomial outcomes. However, even among the few studies that have examined some forms of both volatility and stochasticity systematically played off against one another, they have typically made their dissociation comparatively easy by manipulating volatility by binary jumps of the hidden cause7,9,29 qualitatively different from more graded realization of stochasticity, or have removed the need for computing them by providing explicit information regarding the nature and level of the noise in a specific session30. In real-life situations, however, individuals must rely solely on their observations over time to dissociate these factors.

In a recent article13, we investigated this issue at the computational level. We showed that although it is necessary for adaptive learning to dissociate whether the cause of noise is volatility or stochasticity, it is computationally difficult to do so because both volatility and stochasticity increase the overall noisiness (i.e., variance) of observations. Nevertheless, it is indeed possible to distinguish between volatility and stochasticity due to a subtle yet crucial difference in their effects on the statistical properties of generated observations. In particular, while both increase the variance of observations, volatility increases their autocorrelation while stochasticity decreases it.

We have shown that taking account of this distinction explains a wide range of neuroscience phenomena31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 and reconciles long-standing competing theories in the associative learning literature on whether surprising outcomes decrease31 or increase32 the learning rate by showing that these theories rely on paradigms that, in effect, manipulate either stochasticity or volatility. Furthermore, the distinction between stochasticity and volatility has significant implications for neuropsychiatry. This is because inferring their levels requires disentangling their effects on the observed noise, so that abnormalities in inferring one will tend also to affect the other. Importantly, this implies that much previous work that appeared to demonstrate associations between various psychiatric dysfunction and impaired sensitivity to volatility may instead point to primary or secondary effects mediated by stochasticity (which was typically not manipulated or modeled). We argued that such compensatory tradeoffs may manifest in various disorders that have been previously investigated in the context of volatility, such as learning abnormalities observed in anxiety disorders and following amygdala damage13.

In the current study, we directly test predictions of this theory in two large scale samples of human participants, collected online. We designed a behavioral prediction task that systematically manipulates both volatility and stochasticity in a factorial design while measuring the learning rate. We study these processes directly in terms of prediction, rather than via their downstream consequences on decisions, because this allows us a more detailed view on learning. Our findings reveal that, on average, humans are able to dissociate volatility and stochasticity solely by observing outcomes. Consistent with theoretical expectations, we also observe that volatility and stochasticity have opposing effects on the learning rate in humans. We further show that there is considerable individual variability regarding computations of volatility and stochasticity across humans and present a model that robustly captures these variations. Furthermore, we introduce behavioral signatures to investigate how humans adjust their learning rates on a trial-by-trial basis as a function of local indicators of stochasticity vs volatility. This analysis shows that human behavior is inconsistent with other models of learning rate adjustment that fail to take account of this distinction, but consistent with our learning model, which achieves this dissociation by tracking statistical estimates of variance and covariance and by balancing their dueling effect on the inferred stochasticity signal.

Results

Experiment 1

Participants (n = 223) were recruited from the Prolific Academic platform and performed the behavioral task (see Supplementary Table 1 for demographics). The task aimed to explore situations where observers need to make predictions about a latent factor from a series of observations that are corrupted by both volatility and stochasticity. An example of such situations arises when one aims to predict the intentions of another animal based on observations that are also influenced by external factors beyond the control of the animal. Thus, the noise that influences trial-by-trial changes in the hidden variable (i.e., the animal’s intention) is volatility, and the external noise that is not controlled by the animal is stochasticity.

To this end, we designed a behavioral task that systematically manipulates both volatility and stochasticity in a 2 × 2 factorial setting. Thus, the task was divided into four blocks, with the true volatility and stochasticity values fixed within a block (though participants were unaware of the true values) and changing between blocks. For the cover story, we built on a successful paradigm due to Nassar and colleagues7,9,39, in which participants are asked to move a bucket to collect bags of coins dropped by a bird. Participants did not see the bird, and were instead required to estimate its position based on observations (i.e., the locations of dropped bags) on previous trials (Fig. 1a). Participants were instructed that the bird, unbeknownst to them, moves noisily on a trial-by-trial basis (instantiating diffusion noise whose variance is volatility). Participants were also told that, depending on the wind (instantiating observation noise whose variance is stochasticity), the bag might fall right under the bird, in front of it, or behind it. This scenario allowed us to measure participants’ behavior in relation to the manipulation of true volatility (i.e., noise due to the bird’s movement) and true stochasticity (i.e., noise due to the wind). Participants were also told that they would be playing against four different birds in four different weather conditions, enabling the utilization of a 2 × 2 factorial design in the study. Thus, the goal of the instructions was to make it clear and plausible that there are two different and independent sources of noise, with volatility caused by the variability in the bird’s movement and stochasticity caused by an independent source, i.e., the wind. Furthermore, we utilized several strategies to reduce any prior participant beliefs around volatility and stochasticity. First, as described, we offered a plausible cover story with concrete examples of the various task elements. Second, all participants had to complete a comprehension quiz subsequent to instructions but preceding the task. Third, rather than one extensive instruction then a long practice session, we interspersed short pieces of instructions followed by short practices. Lastly, practice session volatility and stochasticity parameters provided no hint of their true values in the task, using volatility and stochasticity levels almost equal to the average of the two levels used in the actual experiment. Thus, practice could not bias block-level learning rate data through prior value information.

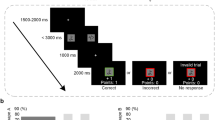

a On every trial, participants move their bucket to catch bags dropped by an invisible bird. Participants cannot move their bucket when the bag appears on the screen. The task has four blocks with a 2 × 2 factorial design, manipulating both true volatility and true stochasticity. b The task follows a 2 × 2 factorial design with true stochasticity and true volatility as factors, each with two levels: small or large. True volatility determines the variance of diffusion noise in the hidden cause (caused by the bird’s movement), while true stochasticity determines the variance of observation noise (caused by wind). The small and large values of true volatility were 4 and 49, respectively. For true stochasticity, the small and large values were 16 and 64, respectively. c Time-series of observations (i.e., bags) in the task. The black line is the hidden cause (i.e., the bird) that is invisible to participants. d Optimal statistical modeling approach indicates that volatility and stochasticity should have opposite effects on the learning rate in this task. Therefore, adaptive learning requires dissociating volatility from stochasticity. e Both factors increase the variance of observations, which makes their dissociation computationally challenging. f It is possible to dissociate volatility from stochasticity because they have opposite effects on the autocorrelation of observations. While stochasticity reduces the autocorrelation, volatility increases it.

In contrast to previous studies7,9,39 that employed substantially different generative processes to manipulate volatility and stochasticity (such as binary versus continuous), we assumed that both diffusion and observation noise are Gaussian, which presents a greater challenge in distinguishing between them. Additionally, the optimal learning approach in this scenario is represented by a widely known Bayesian model called the Kalman filter40. According to the principles of the Kalman filter, the learning rate is expected to increase with higher volatility and decrease with higher stochasticity. However, since humans do not have access to the true values of volatility and stochasticity, they must infer these factors based on their observations. Importantly, as mentioned earlier, although both volatility and stochasticity contribute to an increase in the variance of observations, they exert opposite effects on their autocorrelation. This distinction arises from the definition of autocorrelation, which is the covariance between observations on successive trials divided by the variance of observations. Volatility directly increases autocovariance and its impact on the variance is secondary, resulting in an overall increase in autocorrelation. On the contrary, stochasticity does not affect autocovariance but instead increases variance, leading to a decrease in autocorrelation. This crucial distinction implies that individuals with statistically efficient learning abilities can differentiate between the two factors solely based on observations.

Model-agnostic analysis

For this task, it is straightforward to calculate an estimate of the learning rate per block in a model-agnostic manner7,9. Since the learning rate is formally equal to the ratio of the update in the prediction (directly revealed by the bucket’s location on the current trial minus its location on the previous trial) to the prediction error (the bag’s location on the current trial minus the bucket’s location on the previous trial), we can use linear regression to estimate an average learning rate coefficient by regressing the update against the prediction error across trials. This allows us to quantify the main effects of both noise factors (true volatility and true stochasticity) as well as their interactions. In the analysis, we also included regressors modeling any effect of nuisance factors that are independent of the prediction error. We note that the learning rate as estimated this way is a useful descriptive statistic to measure the amount of updating, even if the true learning rule is not implemented via an error-driven update.

Figure 2a shows the results of this analysis (also see Supplementary Table 2). Across all participants, we found that the effect of prediction error on the update (i.e., the learning rate) was significantly dependent on both true volatility (t(222) = +5.6, p < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (0.03, 0.06)) and true stochasticity (t(222) = –6.4, p < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.08, −0.04)), with the effects having opposite signs as expected. We found no significant interaction effect (t(222) = –0.4, P = 0.68, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.02, 0.01)), and the effect size in terms of true stochasticity and true volatility did not correlate significantly (r(221) = 0.06, P = 0.35). These results indicate that humans dissociate stochasticity and volatility solely based on observations. Also, it reveals that these two factors have opposite effects on human learning. Volatility increases the human learning rate, and stochasticity decreases it. This result goes beyond previous work studying these factors separately6,7,8. This analysis also reveals that these factors have a main effect on behavior, regardless of the prediction error (Supplementary Table 2), which is not directly predicted by the model (but may simply reflect the coding of the simple effects in the presence of an interaction). These effects cannot be attributed to block order, since we have randomized the order of blocks across participants, and a mixed-effects analysis similar to the one reported here but with additional per-participant regressors revealed no significant effect of the first block on learning rate across participants (P > 0.3, see also Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Materials for details) while all other effects remained significant. Notably, the learning rate (computed trial-by-trial and visualized across participants, Fig. 2) fluctuated dynamically over time, suggesting that participants updated their estimate of task factors on a trial-by-trial basis. This is an aspect of data that we investigate later using a process level model that is able to adaptively learn volatility and stochasticity.

a Mean Learning rate coefficients obtained from the model-agnostic regression analysis are plotted (n = 223). For each block, we regressed the update (in the bucket position) against the prediction error (the difference between the bag and the bucket). The corresponding regression coefficient is the learning rate coefficient in that block. This analysis reveals strong main effects of both factors, in line with model predictions plotted in Fig. 1c. b Main effects of both factors on the learning rate coefficient have been plotted for all participants (n = 223). c Dynamics of learning rate coefficients across all participants suggest that participants update their learning rate dynamically over time based on their observations. Mean and standard error of the mean are plotted in all panels.

Importantly, although there are strong effects of both factors on average, we also see notable individual variability in the data (Fig. 2b). As shown in Fig. 2b, almost 30% of participants showed opposite effects in terms of stochasticity (i.e., increases in learning rate with increases in true stochasticity) and 35% showed opposite effects in terms of volatility (i.e., decreases in learning rate with increases in true volatility) in this analysis. Moreover, these maladaptive learners generally showed reduced performance in the task (Z = −1.7, P = 0.09), and the effect was mostly driven by maladaptive volatility learners (Z = −2.3, P = 0.02), with the other group showing a nonsignificant reduced performance (Z = −1.5, P = 0.13).

It is also informative to investigate participants’ learning rate data relative to the ideal learning rate that can be defined using true values of volatility and stochasticity (Fig. 1d). Participants generally showed an elevated learning rate compared to the ideal learning rate, and the effect was specifically larger for the low volatility blocks. In the context of a model where learning rate is determined by estimates of noise, this suggests that participants misestimated volatility, or stochasticity, or both in those blocks. Interestingly, this generally led to better performance in the large true volatility blocks, in which performance error was smaller than variance of the observations (Z < −11.2, P < 0.001), while in the other two blocks performance error was generally larger than the variance of observations (Z > + 11.5, P < 0.001).

Individual variability in dissociating volatility and stochasticity

A major goal of this research is to characterize individual differences in these learning processes, in order (in future) to study how they may be affected in neurological or psychiatric disorders. We thus next employed computational modeling to estimate parameters that can characterize these individual differences. Moreover, computational modeling allows us to dissociate variability due to the response stage (e.g., hand movements when positioning the bucket) from variability in the underlying estimation of task variables. We first modeled the task with a Kalman filter with one Kalman uncertainty parameter per block, in which the Kalman parameter encodes the ratio of volatility to stochasticity within the corresponding block. This approach summarizes behavior by in effect assuming that participants estimate volatility and stochasticity with a parameter that only changes between blocks. This is consistent with the objective task setup, but it is a simplified descriptive model from the participants’ perspective in that we abstract away the trial-by-trial dynamics by which they must estimate the true, fixed blockwise parameters from their individual noisy observations within a block. It is important to note that when both stochasticity and volatility are fixed in a Kalman filter, it is only possible to estimate their ratio since they are interdependent (i.e., only their ratio is recoverable). Therefore, the fact that we assume one free parameter per block for the Kalman filter is well-aligned with the theory outlined above. Moreover, since the Kalman filter is a tractable algorithm, this approach results in very robust parameter estimation and almost perfect recoverability (Supplementary Table 4). This enabled us to quantify two key individual-level parameters: sensitivity to stochasticity, \({\lambda }_{s}\) (i.e., differential effects of true stochasticity on the Kalman parameter), and sensitivity to volatility, \({\lambda }_{v}\) (i.e., differential effects of true volatility on the Kalman parameter) along with two additional parameters capturing main (\({\lambda }_{m}\)) and interaction effects (\({\lambda }_{i}\)) on the Kalman parameter. Note that the parameters of this model are simply a linear translation of the parameters of a Kalman model, with one Kalman parameter per block.

Different sets of \({\lambda }_{s}\) and \({\lambda }_{v}\) capture different behaviors in the task. Positive and negative \({\lambda }_{s}\), for example, reflect the normal and pathological impacts of stochasticity on behavior, respectively. As a result, a model with negative \({\lambda }_{s}\) systematically underestimates stochasticity in favor of volatility. Similarly, a model with negative \({\lambda }_{v}\) systematically underestimates volatility in favor of stochasticity. We thus first tested these parameters across all participants. In line with the model-agnostic results, we found that both \({\lambda }_{s}\) and \({\lambda }_{v}\) were significantly positive, on average across all participants (\({\lambda }_{s}\): t(222) = 3.63, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (4.3, 14.4); \({\lambda }_{v}\): t(222) = 4.12, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (5.3, 14.9)), although we also observed substantial individual variation (see Supplementary Table 4). We also considered an alternative simpler Rescorla-Wagner model with a constant learning rate per block. Similar to the Kalman filter, this model also updates its estimate of the bucket position using a delta-rule, but unlike the Kalman filter, it uses a constant learning rate within each block. We then used Bayesian model comparison tools to compare this simpler model with the Kalman filter model. The Bayesian model comparison revealed more evidence in favor of the Kalman filter model (model frequency: 0.63, protected exceedance probability: 0.98), indicating that a dynamic learning rate fits data better than a simpler model with constant within-block learning rate (see Supplementary Materials for details).

To further elucidate different patterns of maladaptive behavior with respect to volatility and stochasticity, we divided the participants into different groups and studied their learning rate coefficients from the model-agnostic analysis (Fig. 3). We examined model-agnostic learning rate coefficients as these directly summarize the behavior (the direction of error-driven learning rate updates) in each group of participants. This analysis revealed that while participants with positive \({\lambda }_{s}\) exhibited adaptive behavior in line with statistical expectations (Fig. 3a), those with negative \({\lambda }_{s}\) systematically underestimated stochasticity in favor of volatility and therefore increased their learning rate with increases in true stochasticity (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, maladaptively remained quite specific. Specifically, those with negative \({\lambda }_{s}\) remained adaptive with respect to the true volatility factor, showing significant increase in learning rate with increases in true volatility (t(64) = +2.2, P = 0.035, %95 Confidence Interval = (0.005, 0.126)). On the other hand, participants with negative \({\lambda }_{v}\) showed prototypical maladaptive behavior in the opposite direction. Specifically, whereas participants with positive \({\lambda }_{v}\) showed statistically adaptive behavior in the task (Fig. 3d), those with negative \({\lambda }_{v}\) systematically underestimated volatility in favor of stochasticity and therefore decreased their learning rate even with increases in true volatility (Fig. 3e). Additionally, maladaptive patterns remained specific. Participants with negative \({\lambda }_{v}\) remained adaptive with respect to the true stochasticity factor, showing significant decrease in learning rate with increases in true stochasticity (t(63) = –4.8, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.25, −0.11)).

a–c Learning rate coefficients from the model-agnostic analysis are plotted for two groups of participants with positive (n = 158) and negative (n = 65) sensitivity to stochasticity quantified using the Kalman model. Negative sensitivity to stochasticity does not merely abolish the corresponding effects on the learning rate but reverses them. Moreover, maladaptive stochasticity learners show adaptive behavior with respect to the true volatility factor. d–f. Learning rate coefficients are plotted for two groups of participants with positive (n = 159) and negative (n = 64) sensitivity to volatility. Similarly, the learning rate coefficients are plotted for two groups of participants categorized by their sensitivity to volatility: one group with positive sensitivity and the other with negative sensitivity to volatility. Negative sensitivity to volatility also goes beyond nullifying the corresponding effects on the learning rate and actually flips them. Moreover, maladaptive volatility learners show adaptive behavior with respect to the true stochasticity factor. Note that the two maladaptive groups do not show substantial overlap, with only 8% of participants exhibiting both types of maladaptively. Mean and standard error of the mean are plotted.

Computational models of learning stochasticity and volatility

The Kalman model provides a robust descriptive summary of subjective parameters driving individual differences in this task. However, it does not model the process from the participants’ viewpoint. This is because although the true generative noise parameters are fixed per-block, participants can only estimate them from their noisy trial-by-trial observations. As shown earlier, there was substantial dynamics in participants’ learning over time. Thus, we developed a hierarchical Bayesian model to capture learning under the precise task conditions experienced by the participants (Fig. 4). In particular, we assume that participants infer the parameters by assuming a hierarchical generalization of the generative model that underlies the Kalman filter. In this hierarchical model, not only is the latent cause (i.e., the bird’s position) unknown and changing, but the values of both volatility and stochasticity are also unknown and changing. The model assumes that both stochasticity and volatility change on every trial based on a Gaussian mixture process driven by two parameters, \({\mu }_{s}\) and \({\mu }_{v}\), which respectively determine the subjective prior probability that stochasticity and volatility change on every trial. Thus, if \({\mu }_{s}\) is closer to one, the probability of stochasticity changing is higher. When \({\mu }_{s}=1\), stochasticity always changes according to a log-normal distribution with a mean given by its value on the previous trial and a fixed variance parameter, \({\sigma }^{2}\). On the other hand, when \({\mu }_{s}=0\), stochasticity always remains the same as the previous trial (equivalent to a Gaussian with zero variance). Thus, the process is mixture of two Gaussians with the weight parameter given by \({\mu }_{s}\). Similarly, volatility is evolved according to a generative process governed by parameters \({\mu }_{v}\) and the same variance parameter \({\sigma }^{2}\). Thus, different sets of these parameters yield distinct learning behaviors in this task, including the statistically adaptive learning behavior as well as the two distinct pathological learning behaviors (in turn, corresponding to reasonable or extreme values of the hyperparameters governing sensitivity to either type of noise).

a Structure of the (generative) model: the observation (e.g., the bag) on trial \(t\), \({o}_{t}\), is generated based on a hidden cause, \({x}_{t}\), (e.g., the bird) plus some independent noise (e.g., wind) whose variance is given by the stochasticity, \({s}_{t}\). The hidden cause itself depends on its value on the previous trial plus some noise whose variance is given by the volatility, \({v}_{t}\). Both volatility and stochasticity are generated noisily based on their value on the previous trial. The learner should infer value of the hidden cause, volatility and stochasticity based on observations. b, c Mean learning rate by the model across participants as a function of the two experimental factors (n = 223). Mean and standard error of mean are plotted in (b). Individual data-points for the two main effects as well as their median are plotted in (c). d, e Dynamics of the stochasticity signal estimated by the model. f, g Dynamics of the volatility signal estimated by the model. Mean and standard error of mean are plotted in (d–g).

Unlike the Kalman filter, which allows for tractable inference, exact inference is not tractable for the hierarchical model. We view this model as a computational-level model, useful both for characterizing the nature of the dynamic learning process and the factors that affect it, and also descriptively characterizing individual differences in the behavior via the hyperparameters. However (as with many Bayesian models), in order to estimate it we must use approximate inference; for this, we choose a relatively accurate approach, though we do not mean any strong mechanistic claim about which approximation participants may use. We have used a standard approximation approach based on particle filtering41,42. Our method leverages the fact that, given a sample of volatility and stochasticity, we can perform tractable inference for the latent cause using the Kalman filter (this hybrid approach is referred to as Rao-Blackwellized particle filtering). However, there is a technical challenge when it comes to parameter estimation with particle filters (and similar models based on Monte Carlo sampling), which has posed a considerable difficulty in applying these models in psychology. The issue arises from the nondeterministic nature of the output of particle filter models. Additionally, the likelihood function is not differentiable with respect to generative parameters. To overcome these challenges, we adopted a number of techniques for model fitting, including utilizing an optimization scheme based on Gaussian processes that is well-suited for particle filter models43,44. We first conducted a recovery analysis where the model was simulated using different sets of known parameters. The resulting time-series data generated by the model were subjected to the same model fitting method. This analysis demonstrated that the parameters of the model are recoverable using this method (Supplementary Fig 1).

We then asked whether the hierarchical Bayesian model (with inference conducted using the particle filter approximation) provides a better account of human response data in this task compared with the Kalman filter model. Bayesian model comparison revealed overwhelming evidence in favor of the hierarchical particle filter model, with the winning model providing a better account for data in 88% of participants (model frequency: 0.86, protected exceedance probability: (1). We also tested model fit against a number of alternative models that also adjust learning rate over time, including delta-bar-delta, a reinforcement learning algorithm with a dynamic learning rate that has been previously used in the literature45,46, an algorithm with a structure similar to Weber’s law of intensity sensation that utilizes a noisy Rescorla-Wagner learning rule47, and the hierarchical Gaussian filter, a well-established model for learning under volatility8,11. All these models have been used as models of human learning in the field in the past, but all fail to distinguish stochasticity from volatility. Accordingly, none provided a better fit than the main models considered here, especially our hierarchical particle filter model (see Supplementary Methods for details of these models and Supplementary Tables 6, 7). Furthermore, all of these alternative models failed to capture key patterns observed in model-agnostic results, which are accurately reproduced by the hierarchical particle filter model (Supplementary Fig 2; Supplementary Table 8). We additionally fitted an alternative Bayesian model. This model assumed volatility and stochasticity values could change between blocks but remained constant within each block. It used Bayesian inference progressively to estimate their level over the course of each block. However, this model also did not fit as well as the more dynamic hierarchical particle filter model.

Returning to the best-fitting hierarchical particle filter model, we next used the model to infer subjective estimates of volatility and stochasticity among participants. First, we verified that the model reflects variations in human learning rate. Using the model to generate predictions, we quantified per-trial learning rates with the same model-agnostic procedure from Fig. 2c. This analysis showed a significant correlation between the model’s learning rate and participants’ empirical learning rate (Spearman rank correlation: r = 0.48, P < 0.001; see also Supplementary Table 9).

Moreover, model estimates of learning rate, volatility, and stochasticity generated based on fitted parameters, on average, show the behavior expected theoretically with remarkable similarity to empirical data. The model’s learning rate showed significant positive and negative main effects of true volatility (Z = 6.8, P < 0.001) and true stochasticity (Z = 12.95, P < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 4). The subjective estimate of stochasticity shows no significant effect with respect to the true volatility factor (Z = −1.26, P = 0.21). As expected, however, it is significantly larger for the blocks with larger true stochasticity (Z = 12.1, P < 0.001). The analysis of the subjective estimate of volatility, however, shows main effects of both true volatility (Z = 13.0, P < 0.001) and true stochasticity (Z = 6.8, P < 0.001). In other words, the subjective estimate of volatility exhibits some degree of misestimation with respect to the true stochasticity factor across all participants. Statistically though, the effect size is much smaller than those with respect to the true volatility factor, indicating that subjective volatility is still primarily sensitive to the true volatility factor, as expected. Finally, as shown in Fig. 4, the model dynamically updates its estimates of stochasticity and volatility over time. Guided by insights from the model, we thus proceed with examining further signatures in the data indicative of the computational mechanism underlying these updates in participants.

Model-agnostic analysis of trial-trial learning rate dynamics

All the previous analyses demonstrate that participants are capable of effectively learning to differentiate between volatility and stochasticity solely through outcome observations. We have also shown that these results are best fit, overall, by a hierarchical particle filter model that makes inference about the degree to which each source contributes to the experienced noise. Therefore, we next investigated model-agnostic signatures in the behavioral data that might reveal the extent to which the trial-by-trial dynamics of participants’ learning are consistent with this account.

First, we explored a simple signature of volatility and stochasticity tracking. Our computational analysis suggests the two are distinguishable in terms of the autocorrelation of the observations (Fig. 1). This difference is, accordingly, reflected in the likelihood function that drives inference about them in the particle filter model. To investigate whether this type of learning affects trial-by-trial updating, we focused on the product of two recent prediction errors, which samples the autocovariance between observations. The sign of this product indicates the sample autocorrelation direction—positive when the product is positive, negative when it is negative. We divided each participant’s trials into two clusters: one with positive values and one with negative values. Our computational analysis predicts learning rate increases after positive autocorrelation, which indicates that volatility underlies the noise in those cases (Fig. 1). Conversely, negative autocorrelation predicts decreases, since it signals that stochasticity instead functions as the primary noise source. We tested how learning rates change on the subsequent trial in these clusters (Fig. 5). First, we verified that the Hierarchical particle filter model (but not the alternative models, Supplementary Fig. 2) shows significant increases in per-trial learning for positive clusters (Z = +12.4, P < 0.001), while showing significant decreases for negative clusters (Z = −10.7, P < 0.001). As expected, this was due to increases in volatility estimate for positive clusters (Z = +13.0, P < 0.001), and increases in stochasticity estimate for negative clusters (Z = +12.0, P < 0.001). We then proceeded to repeat this analysis utilizing the participants’ trial-by-trial learning rates. These were estimated in a model-agnostic manner based on the trial-by-trial bucket positions resulting from participants’ actions. Critically, this signature held for participants’ data too: learning rates significantly increased for positive clusters (t(222) = +10.1, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (0.028, 0.041)) and significantly decreased for negative clusters (t(222) = −10.0, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.036, −0.024)).

a, b Effects of two clusters of trials, one with negative sample autocorrelation (i.e., when the product of two recent prediction errors is negative) and another one with positive sample autocorrelation on subsequent changes in volatility estimate, stochasticity estimate. These two clusters have opposite effects on changes in volatility and stochasticity. The box plot displays the median across all participants (n = 223), first and third quartiles, outliers (computed using the interquartile range), and minimum and maximum values that are not outliers. c These two clusters have opposite effects on changes in the model’s learning rate. Learning rate decreases following negative sample autocorrelation, indicating that the experienced noise on those trials is primarily caused by stochasticity. The opposite is true for trials with positive sample autocorrelation, in which the learning rate increases. d Model-agnostic analysis revealed that participants’ learning rates calculated independently of the model based on the trial-by-trial bucket position show similar effects. There is a significant reduction in learning rate for the negative cluster, and a significant increase in learning rate for the positive cluster. Mean and standard error of the mean are plotted in (c, d) (n = 223) alongside data points, the empirical distribution and the mean.

Next, we unpacked in more detail how estimated outcome autocorrelation relates to the learning rate. In particular, the prediction of the hierarchical particle filter model is different from models such as delta-bar-delta45,46, in which the learning rate is directly calculated or updated according to the autocorrelation. In the latter type of models, a larger magnitude of autocorrelation is expected to lead to greater increases or decreases in the learning rate. In contrast, the particle filter model predicts the opposite: that smaller autocorrelations lead to even more substantial trial-by-trial learning rate changes. This perhaps counterintuitive prediction arises because the model evaluates evidence to attribute experienced noise to either volatility or stochasticity. When autocorrelation approaches zero, even small fluctuations can significantly impact this attribution. For instance, a slightly positive autocorrelation might attribute noise to volatility, while a slightly negative one in the next trial might attribute it to stochasticity. These rapid attributional shifts near zero autocorrelation cause larger learning rate fluctuations.

We conducted another model-agnostic analysis to evaluate these predictions (Fig. 6). We regressed the magnitude of trial-by-trial changes in learning rate against the absolute value of sample outcome autocorrelation, i.e., the absolute value of the product of two recent prediction errors. We also included the sample outcome autocorrelation itself as a control regressor. In line with the particle filter model’s prediction, this analysis revealed a significant negative relationship between the magnitude of outcome autocorrelation and the size of changes in the learning rate (t(222) = −15.4, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−5.2357e-04, −4.0454e-04)). In other words, changes in learning rate are larger on trials with smaller, closer-to-zero autocorrelation magnitudes. This is consistent with a model in which autocorrelation is used to attribute experienced noise to one of the two sources. The hierarchical particle filter model shows the same effect (t(222) = −17.1, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−3.3164e-04, −2.6306e-04)).

a Regression coefficients are plotted for the relationship between trial-by-trial sample outcome autocorrelation magnitude, |AC | , and changes in model’s learning rate magnitude, |LR | . The trial-by-trial sample outcome autocorrelation magnitude, |AC | , is negatively related to changes in learning rate magnitude, |LR | . This occurs because the model evaluates evidence to attribute experienced noise to either volatility or stochasticity, a process more consequential for smaller, near-zero values of |AC | . b Changes in |LR| as a function of |AC| are plotted for 10% quantiles. c, d A similar effect to that in (a, b) was found in model-agnostic trial-by-trial learning rate data. e Trial-by-trial response time data show a negative relationship with |AC | , suggesting that trials with smaller |AC| are more challenging, presumably because identifying the noise source is more difficult on these trials. f Response time as data a function of |AC| are plotted for 10% quantiles. In (a, c, e), the mean, standard error of the mean, individual data points, empirical distribution, and median are plotted for all participants (n = 223). In (b, d, f), the mean and standard error of the mean across all participants are plotted.

In the model, the ratio of estimated volatility to stochasticity is the key factor that influences the learning rate. Thus, we repeated this analysis with the log-ratio of changes in volatility to changes in stochasticity as the dependent variable, and the same regressors as independent variables. As expected, this analysis revealed a significant negative relationship with the magnitude of autocorrelation (t(222) = –20.0, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.0085, −0.0070)).

To further test these predictions, we analyzed response times, which we thought might reveal additional signatures indicative of process-level computation. We hypothesized that responses would be slower when identifying the noise source is more challenging. In our model, this occurs when outcome autocorrelation approaches zero. The particle filter model predicts this because near-zero autocorrelation causes particles to conflict with each other. In contrast, models adjusting learning rates proportionally to autocorrelation do not offer any clear reason to see such effects. We performed another regression analysis, examining the relationship between trial-by-trial response time and the absolute value of sample outcome autocorrelation (i.e., the absolute value of the product of two recent prediction errors). We also included the sample outcome autocorrelation itself as a control regressor. This analysis revealed a significant negative relationship between response time and the magnitude of autocorrelation (t(222) = –6.9, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−1.8556e-05, −1.0283e-05)).

Replicating results of Experiment 1 in Experiment 2

In Experiment 1, we documented significant evidence that, on average, humans differentiate between volatility and stochasticity solely through outcome observations and adjust their learning rate adaptively. However, we also observed considerable individual variability among participants. To validate the findings of Experiment 1, we conducted Experiment 2 (n = 420), which aimed to replicate the results. Among other aspects, we specifically tested whether maladaptive participants performed worse than the other groups, an effect that was just short of significance in Experiment 1 for maladaptive stochasticity learners. In Experiment 2, however, the performance of both maladaptive stochasticity learners (Z = −3.9, P < 0.001), as well as maladaptive volatility learners (Z = −2.9, P = 0.004), was significantly worse than their corresponding adaptive learners. We further repeated all the analyses performed in Experiment 1 and replicated all the main results. In Figs. 7 and 8, we present the results and corresponding statistics (see also Supplementary Tables 10–13).

a, b Learning rate coefficients obtained from the model-agnostic regression analysis (n = 420). This analysis revealed significant effects of true stochasticity (t(419) = –9.65, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.0778, −0.0515)) and true volatility (t(419) = +4.15, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (0.015, 0.041)) and no significant interaction (t(419) = +0.50, P = 0.62, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.009, +0.015)). The main effects are plotted in (b). c–e Learning rate coefficients from the model-agnostic analysis are plotted for two groups of participants with positive and negative sensitivity to stochasticity quantified using the Kalman model. Maladaptive learners of one factor generally remained adaptive with respect to the other factor. Specifically, the group with negative \({\lambda }_{s}\) (n = 121, 29% of participants) showed significantly adaptive learning rate with respect to true volatility (t(120) = +2.87, P = 0.005, %95 Confidence Interval = (0.027, 0.145)). f–h Learning rate coefficients from the model-agnostic analysis are plotted for two groups of participants with positive and negative sensitivity to volatility quantified using the Kalman model. Maladaptive volatility learners also were adaptive with respect to stochasticity. The group with negative \({\lambda }_{v}\) (n = 141, 33% of participants) showed significantly adaptive lower learning rate coefficients with increases in true stochasticity (t(140) = −4.66, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.162, −0.065)). Mean and standard error of the mean are plotted. Two-sided t-tests are reported. See also Supplementary Tables 10–12.

a Effects of sample autocorrelation on learning rate in Experiment 2. Analysis of two clusters with negative and positive sample autocorrelation revealed that the learning rate increases following positive sample autocorrelation (t(419) = +12.0, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (0.028, 0.039)) and decreases following negative sample autocorrelation (t(419) = −12.4, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−0.034, −0.025)). This was seen in both the model learning rate and the model-agnostic learning rate, which was estimated independently of the model based on trial-by-trial behavioral data. The bar plot on the left shows the mean and standard error of the mean, and the plot on the right shows individual data points across all participants. b, c The relationship between magnitude of sample outcome autocorrelation |AC| and magnitude of changes in learning rate in Experiment 2 is negative for both the model and the model-agnostic learning rate (t(419) = −23.0, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−5.9546e-04, −5.0165e-04)). d Trial-by-trial response time shows a negative relationship with |AC | , suggesting that trials with smaller |AC| are more challenging, presumably because identifying the noise source is more difficult on these trials (t(419) = −10.5, P < 0.001, %95 Confidence Interval = (−2.0335e-05, −1.3930e-05)). Mean and standard error of the mean are plotted in (a–d), alongside individual data points and their empirical distribution. Two-sided t-tests are reported. See also supplementary Tables 13.

Discussion

To learn effectively in noisy environments, it is crucial to be able to distinguish between different types of noise. Volatility and stochasticity are two such types, each playing important but contrasting roles in the learning process. However, the challenge arises from the fact that both volatility and stochasticity increase the variance of observations and introduce interdependencies during their estimation. This makes it computationally demanding to separate them. To address this issue, we conducted two large-scale experiments to investigate whether and how human participants differentiate between volatility and stochasticity based solely on their observations. Our findings revealed that, on average, humans can successfully discriminate between the two and adjust their learning rate accordingly. Specifically, we observed that, across all participants, learning rates increased with higher levels of volatility and decreased with higher levels of stochasticity. These results, and numerous detailed aspects of learning, were consistent with a hierarchical particle filter model that estimates both stochasticity and volatility, but not with a number of earlier models that fail to make this distinction. Also consistent with theoretical considerations, in addition to the majority of participants who made adaptive responses to both volatility and stochasticity, we identified two distinct subgroups among participants, each exhibiting characteristic patterns of systematic errors and maladaptive learning. One subgroup displayed insensitivity to stochasticity, while the other subgroup showed insensitivity to volatility.

Previous research has demonstrated that humans can adapt their learning rates in response to manipulations of either type of noise6,8,12,29,30,48. However, previous studies have generally overlooked the more challenging task of distinguishing between these noise types by manipulating only one source (often volatility, with stochasticity changing only incidentally), employing significantly different statistical generative processes for each type (e.g., binary vs Gaussian), or manipulating them in different conditions with explicit instructions about the type of noise. This neglect is inconsistent with real-life situations where we must differentiate between volatility and stochasticity based solely on our own observations.

The current work is an empirical study testing predictions of our recent theory in a general population of human participants13. In that work, we showed the computational challenges of inferring volatility and stochasticity when both are unknown and changing and showcased the potential interdependence between the two factors across various situations. Following the analyses of that work, we designed an experiment in which true values of both volatility and stochasticity were systematically manipulated in a 2 × 2 factorial design. We further followed the general task design by Nassar et al7,39., which allows for a model-agnostic estimation of learning rate. This enabled us to quantify participants learning rate as a function of experimental factors independent of assumptions often made in model fitting analyses.

In line with our theoretical work, we identified two subgroups of participants exhibiting distinct maladaptive learning patterns in the task. Approximately 30% of participants in both experiments displayed pathological insensitivity to stochasticity, resulting in a significant increase in their learning rate as stochasticity increased. Conversely, around 30% of participants demonstrated pathological insensitivity to volatility, leading to a significant reduction in their learning rate even in more volatile conditions. This approach has the potential to shed light on various brain disorders that impact uncertainty processing, which have primarily been studied in the context of volatility in recent years16,17,18,23,24,26,27,28. We have recently developed these ideas specifically in relation to pathological decision making in anxiety15,21,25,49,50,51,52,53. We proposed that the current evidence aligns more closely with hyposensitivity to stochasticity, which triggers an oversensitivity to volatility due to the compensatory mechanism. The combination of our behavioral paradigm, computational models, and parameter estimation method enables a reexamination of this research program, with a particular emphasis on understanding the interplay between volatility and stochasticity, which presents a more challenging computational problem compared to estimating each factor in isolation.

We also developed a process-level hierarchical particle filter model that adjusts volatility and stochasticity based solely on observations. Similar to how participants are presented with task, this model initializes each block with the same initial set of parameters and updates its estimates of volatility and stochasticity on a trial-by-trial basis. This modeling approach allowed us to investigate the computational mechanisms underlying the learning of volatility and stochasticity in participants. Building on our theoretical analyses (Fig. 1), we examined a simple signature of this type of learning, by dividing trials into those with a positive recent experience of autocorrelation versus a negative one (Fig. 5). The sign of autocorrelation can be readily defined as the sign of the product of two recent prediction errors. Positive autocorrelation indicates volatility is more likely the actual source of experienced noise. Therefore, we expected to see increases in learning rate following periods of positive autocorrelation. Conversely, negative autocorrelation suggests stochasticity is more likely driving the noise. Hence, we predicted decreases in learning rate after such periods. Our analysis revealed strong effects of these recent autocorrelation experiences on changes in learning rate, both in the model and in the data. Periods of positive autocorrelation preceded rises in learning rate, while periods of negative autocorrelation preceded learning rate reductions.

Additionally, analysis of response times revealed a significant negative correlation with autocorrelation magnitude. Participants responded more slowly on trials where autocorrelation approached zero, perhaps indicating increased cognitive load. This effect makes sense under the hierarchical model: on each trial, it probabilistically attributes experienced noise to volatility or stochasticity by weighing evidence from recent outcomes. This attribution process becomes more ambiguous (and perhaps more computationally intensive) when autocorrelation nears zero because the evidence for either source becomes equivocal. The concordance between model-predicted processing demands and observed response times provides independent corroboration for the model’s trial-by-trial evidence evaluation mechanism, a key feature distinguishing it from simpler learning models.

Overall, these findings—together with the findings that a number of simpler models that fail to take account of the stochasticity vs volatility distinction suggest that people are relying on similar computations to solve the task. Of course, we cannot and do not mean to rule out variants that implement similar principles via different means, e.g., covertly representing the space of stochasticity vs volatility via some change of variables or even (though we are not aware of any way to accomplish this) via a one-dimensional summary like the learning rate or the Kalman parameter that captures the key tradeoff between them.

This work builds directly upon a substantial body of research that has investigated the processes involved in estimating volatility in both behavior and the brain6,8,12,20,27,54,55. In terms of volatility, our study aligns with and expands upon these previous investigations by focusing on continuous random walks instead of binary switches. Following Behrens et al.6, studies in neuropsychiatry have examined volatility using behavioral tasks that involve binary hidden causes with switching probabilities. Volatility in those studies have been manipulated as the rate of switch. However, computational models that were often used with these tasks are built on the Kalman filter’s generative assumptions in which volatility is the variance of the Gaussian diffusion noise11,14. Thus, these modeling approaches were often incongruent with the generative assumptions of those tasks14. In contrast, our study manipulates volatility by changing the variance of Gaussian diffusion noise, which not only aligns the computational problem with normative analyses provided by the classical Kalman filter, but also ensures a clean separation between manipulation of volatility and manipulation of the hidden cause. This has important implications for the robustness and interpretability of parameter estimation in the application of our behavioral task and model in psychiatric research.

Unlike volatility, stochasticity has not been extensively studied, even in isolation, although previous evidence generally supports our findings regarding stochasticity. Two notable studies, Dierden and Schultz48 as well as Lee et al.30, reported reductions in learning rate with higher levels of stochasticity. However, both studies rendered the learning of stochasticity and its differentiation from volatility trivial by explicitly instructing participants about the nature and level of noise. Several studies by Nassar and colleagues7,9,29,39 primarily focused on the effects of jumps in reward rates (resembling volatility) and reported relatively weak or mixed evidence regarding stochasticity. Therefore, to our knowledge, our study is the first to provide evidence of human participants exhibiting adaptive responses to stochasticity in changing environments. Lee et al.30 performed two separate experiments that manipulated either volatility or stochasticity individually, but not simultaneously. They found opposing effects on learning rate for the two factors, aligning with theoretical predictions. However, their paradigm did not require computation of either factor by participants. Rather, in their design, participants were explicitly told the levels of volatility or stochasticity at the start of each block. This removed the need to infer the source of noise, in contrast to our paradigm requiring joint estimation of both factors from experience.

In a recent preprint, Pulcu and Browning utilized a 2 × 2 factorial design similar to ours to study the effects of volatility and stochasticity on binary observations56. Unlike our work, however, they failed to find any significant effect with regards to stochasticity (or “noise” in their terminology). Notably, their sample size (n = 70) was smaller than ours (Experiment 1: n = 223, Experiment 2: n = 420). This highlights the importance of our results as well as the robustness of the current experimental design, which allowed us to establish opposing effects of both volatility and stochasticity on learning rate as expected theoretically. While it is not possible to draw any conclusion based on null effects, the discrepancy in findings might be related to differences in effects of stochasticity on binary observations, which should be addressed both conceptually and empirically in the future.

One notable methodological contribution of this study is the development of a fitting procedure specifically tailored for particle filter models41,42, along with the validation of its reliability and robustness for the current research context. Unlike traditional cognitive models, parameter estimation for particle filter models is known to be challenging57,58, which has limited their application in psychology. The difficulty stems from the non-deterministic nature of the likelihood function in particle filter models, as well as the lack of differentiability of the likelihood function with respect to the generative parameters. To address this, we employed a nonlinear optimization method based on Gaussian processes43,44. We successfully demonstrated that the model parameters are recoverable, and the estimates are robust across participants. Beyond the current application, this work enhances the practical utility of particle filter models in psychological research.

The primary focus of this study was to measure the influence of volatility and stochasticity on learning. However, uncertainty is a significant factor in various other cognitive processes, and gaining insights into how individuals perceive volatility and stochasticity, and their impact on uncertainty, could have broad implications for behavior. These additional issues include attention2, decision noise and the explore-exploit tradeoff47,59, social cause inference27,60,61, the organization of experiences into latent causes or contexts5,62,63, and planning64,65,66,67. By adapting variants of the current task and employing similar computational modeling approaches, we can directly address these problems in diverse behavioral domains.

Methods

Participants and procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Princeton University. Participants were recruited via the Prolific Platform. For Experiment 1, a total of 236 participants participated in exchange for monetary compensation. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size for Experiment 1. 13 participants failed the comprehension quiz and were therefore excluded from the behavioral task. The remaining participants successfully passed the main quality checks of the study: (i) they did not exhibit outlier behavior by leaving the bucket untouched for extended periods of time; and (ii) each participant demonstrated a significant positive effect associated with the prediction error signal (P < 0.001) indicating a consistent tendency to move towards the position of the bag. In Experiment 2, a total of 490 participants participated. The sample size was chosen to allow for adequate statistical power to analyze individual differences based on the findings from Experiment 1. 70 participants failed the comprehension quiz and were excluded from the behavioral task. The remaining 420 participants successfully passed the quality checks.

The task was implemented using JavaScript and made accessible through NivTurk68. All participants gave informed consent. Participants began by reading the instructions, engaging in practice exercises to familiarize themselves with various task aspects, and completing two comprehension quizzes to ensure their attention and understanding. They then proceeded to perform the behavioral task. Following the completion of the behavioral task, participants undertook another task and filled out two questionnaires, which served as pilot data for another study. In Experiment 2, two other pilot questionnaires were also administered prior to the instructions and the behavioral task.

Behavioral task

Participants were asked to move a bucket to collect bags of coins dropped by an invisible bird. Observations (i.e., bags) were generated based on a Markovian random walk with Gaussian diffusion noise and Gaussian observation noise. The volatility and stochasticity represented the variance of the diffusion and observation noise, respectively. We created four timeseries in a 2 × 2 setting, where the true volatility was either 4 or 49, and the true stochasticity was either 16 or 64 (Fig. 1). It is worth noting that only the ratio of volatility to stochasticity is relevant for inference, as explained in the Kalman modeling section below. Prior to the reported experiments, we conducted pilot tests with different combinations of true volatility and stochasticity values. The observed behavior was generally consistent with our theoretical expectations, and we selected the current set of values due to their robust effects. The order of the experimental blocks was randomly assigned to participants. Each block consisted of 50 trials and began with a cartoon image of a bird (randomly selected) along with the phrase: “new bird and new wind condition.” Each trial began with the participant having the ability to move the bucket, followed by a frozen screen where bucket movement was disabled, and a bag falling from the sky. The initial position of the bucket on each trial corresponded to its position when the screen froze on the previous trial, except for the first trial of each block, which started from the middle of the screen. Participants were allowed to keep the bucket in the same position for a few trials, but they received a warning if they left it untouched for an extended period. Step-by-step instructions were provided to participants, covering various aspects of the task, including: (1) informing them that their task is to move the bucket to collect bags of coins dropped by the bird; (2) acknowledging that the bird’s movement was random and the best estimate of its position was its position on the previous trial; (3) recognizing that the bag’s fall location near the bird was random due to wind conditions, which could result in it falling directly below, in front of, or behind the bird; (4) acknowledging that the bird was not visible due to foggy conditions; and (5) informing them that they would encounter four different birds in four distinct wind conditions. Participants engaged in practice trials for two versions of the task: a few trials where they could see the bird and subsequent trials resembling the actual task, where the bird was invisible.

Participants’ performance in the task was calculated by taking the median of block-wise error scores (since the distribution of errors was non-normal). For each block, we computed the error score as the mean of squared difference between the participant’s predictions and the actual outcomes.

Model-agnostic blockwise analysis

We performed a within-subject linear regression analysis with the update signal (\(u,\) bucket position on the current trial minus its position on the previous trial) as the dependent variable. We included eight regressors as independent variables, encoding the effects of task factors on the prediction error signal (\(\delta,\) the bag position minus the bucket position) per block and the intercept per block:

where \(u\) is the update vector across all trials, \(\delta\) is the prediction error signal across all trials, \(S\) is a binary vector encoding block-wise small (-1) or large true stochasticity levels, \(V\) is a binary vector encoding block-wise small (-1) or large true volatility levels, and \(I\) is the intercept. This quantifies the main effect of the prediction error (i.e., the coefficient of \(\delta\) regressor), its interaction with either true stochasticity (the coefficient of \(\delta \,*\, S\)) and true volatility (the coefficient of \(\delta \,*\, V\)) as well as their three-way interaction (the coefficient of \(\delta \,*\, S \,*\, V\)). This also enabled us to calculate error-independent block effects, namely the effect of either true volatility or true stochasticity and their interaction. The reported statistics were derived t-tests conducted on the corresponding effect across participants (i.e., equivalent to random effect analysis). See also Supplementary Table 2.

Kalman modeling analysis

Kalman filter makes inference about the hidden cause (i.e., the bird) based on volatility and stochasticity as given parameters. The Kalman filter represents its beliefs about the hidden cause at each step as a Gaussian distribution with a mean, \({m}_{t}\), and variance, \({w}_{t}\). The update, on every trial, is driven by a prediction error signal, \({\delta }_{t}\), and learning rate, \({\alpha }_{t}\). This leads to simple update rules following the observation \({o}_{t}\):

where \(v\) and \(s\) are volatility and stochasticity parameters. Importantly, however, it is not possible to recover both parameters with model fitting, because they are fully interdependent from the inference viewpoint. To see this, we can write Eqs. 3 and 4 in a slightly different form as a function of a single Kalman parameter, \(\kappa\):

where \(\kappa=v/s\) and \({u}_{t}={w}_{t}/s\). This means that from the inference viewpoint, only the ratio of volatility to stochasticity, i.e., \(\kappa\), matters.

For model fitting, we considered one Kalman parameter per block and parameterized the model based on four parameters defining the baseline Kalman parameter (i.e., the average across all blocks, \({\lambda }_{m}\)), along with main effects of true stochasticity (low minus high; referred to as the subjective sensitivity to stochasticity, \({\lambda }_{s}\)), true volatility (high minus low, referred to as subjective sensitivity to volatility, \({\lambda }_{v}\)), and their interaction (\({\lambda }_{i}\)) on the Kalman parameter. We used a constrained gradient-based nonlinear optimization scheme (MATLAB’s fmincon) for minimizing the following error function and fit these four parameters:

where \({b}_{t}^{i}\) is the participant’s bucket position on trial \(t\) of block \(i\).

The Kalman model with three parameters were defined similarly by setting \({\lambda }_{i}=0\). For model comparison between the two Kalman models, we used Bayesian information criterion to properly account for different number of parameters between the two models.

Hierarchical particle filter model

Unlike the Kalman filter, the hierarchical particle filter model starts every block from the same starting point and learn values of volatility and stochasticity based on observations. We assumed that volatility evolves according to a mixture of log-normal distributions. Specifically, volatility on trial \(t\) is defined as:

where \({\bar{v}}_{t}=\log {v}_{t}\), \({z}_{v}\) is a binary random variable drawn from a Bernoulli distribution with parameter \({0\le \mu }_{v}\le 1\), and \(\delta\) denotes the Dirac delta function. When \({z}_{v}=0\), volatility remains the same as the previous trial. On the other hand, when \({z}_{v}=1\), volatility follows a log-normal random walk with a variance of \({\sigma }^{2}\). Therefore, the log-volatility exhibits a mixture distribution with \({\mu }_{v}\) as the weight parameter. A similar generative process was defined for the stochasticity variable, \({s}_{t}\), parametrized by \({\mu }_{s}\) and \({\sigma }^{2}\).

For inference with this generative model, we utilized a Rao-Blackwellised Particle Filtering approach41. This approach involves employing a particle filter42 for inference on \({v}_{t}\) and \({s}_{t}\) and subsequently, utilizing the Kalman filter for inference on the hidden cause, conditioned on the particles for \({v}_{t}\) and \({s}_{t}\). The particle filter is a Monte Carlo sequential importance sampling method that estimates the underlying distribution by sequentially refining a set of particles along with their associated weights. The algorithm consisted of three steps for each trial. First, in a prediction step, each particle underwent a transition to the next step based on the generative process. Second, the particle weights were updated based on the probability of the current observation:

where \({a}_{t}^{l}\) is the weight of particle \(l\) on trial \(t\), \({m}_{t-1}^{l}\) and \({w}_{t-1}^{l}\) are estimated mean and variance by the Kalman filter on the previous trial (Eqs. 1–4), and \({v}_{t}^{l}\) and \({s}_{t}^{l}\) are the samples for volatility and stochasticity. Note that this process was conducted separately for each block, but we omitted the index of block to keep the notation uncluttered. During this step, particles were also resampled using the systematic resampling procedure69 if the ratio of effective particles to total particles falls below 0.5.

In the third step, the Kalman filter was utilized to update the mean and variance. Specifically, for each particle, Eqs. 1–4 were employed to update \({m}_{t}^{l}\) and \({w}_{t}^{l}\) for every particle. Variables of interest on trial \(t\) were defined as the weighted average of all particles, in which the weights were given by the particle weights. In all blocks, the initial values for volatility and stochasticity were set to 1, while the initial value for \(w\) was set to 10.

Model fitting procedure for the hierarchical particle filter model

It is notoriously difficult to fit parameters of a particle filter model due to its nondeterministic nature and lack of differentiability with respect to the generative parameters. Therefore, we employed a gradient-free optimization method based on Gaussian process, implemented in MATLAB’s bayesopt routine. To compute the objective function, we used the predictions by the model and calculated the error as the squared distance between the predictions and the participant’s bucket position. For every set of parameters, we repeated this process 10 times using different randomization seeds. We then utilized a regularized objective function for optimization, defined as the mean over the errors across all seeds plus its standard error of the mean. Regularization helps mitigate the issue stemming from the non-deterministic nature of the particle filter process and results in a set of parameters that reliably minimizes the error function. For optimization, we constrained the \({\sigma }^{2}\) in the range of 0.1 and 1. For model comparison between the hierarchical and Kalman model, we used Bayesian information criterion to account for different number of parameters between the two models.

For the recovery analysis, we generated 100 synthetic datasets by simulating the particle filter with randomly chosen parameters for \({\mu }_{s}\), \({\mu }_{v}\) and \({\sigma }^{2}\) and defined the mean prediction as the bucket’s position on each trial. We subsequently applied the same fitting procedure to these synthetic datasets. The analysis revealed a high level of recoverability for all three parameters (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Model-agnostic analysis of trial-trial learning rate dynamics

For each participant, we used the bucket position to define the trial-wise update (change in prediction) and prediction error (outcome minus prediction) values. The per-trial learning rate was then calculated as the update divided by the prediction error, bounded between 0 and 1 (set to 0 if negative and 1 if greater than 1). We also divided trials into two clusters based on the direction of sample autocorrelation, specifically the sign of the product of prediction errors on the two recent trials. This allowed us to examine how learning rate changes were modulated by the local outcome autocorrelation structure. The changes in learning rate were calculated separately for each cluster.

All reported statistical tests are two-sided. We performed parametric tests (e.g., t-test), unless the data were expected to not be normally distributed, in which case appropriate nonparametric rank tests were conducted. When analyzing the response time data, we first excluded trials where the response time was identified as an outlier. To detect outliers, we used MATLAB’s is outlier routine, which flags data points greater than three scaled median absolute deviations as outliers. In the corresponding regression analysis, we regressed the response time on any trial against |AC| and AC on the previous trial. An intercept was included in all regression analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated in this study have been deposited as a Zenodo open repository70 and is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13840905.

Code availability

Analyses were conducted using custom code written in MATLAB (2022a). The code70 is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13840905.

References

Dayan, P. & Long, T. Statistical Models of Conditioning. 10, 117–123 (1998).

Dayan, P., Kakade, S. & Montague, P. R. Learning and selective attention. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 1218–1223 (2000).

Courville, A. C., Daw, N. D. & Touretzky, D. S. Bayesian theories of conditioning in a changing world. Trends Cognit. Sci. 10, 294–300 (2006).