Abstract

The anterior cruciate ligament is anchored to the femur and tibia via specialized interfaces known as entheses. These play a critical role in ligament homeostasis and joint stability by transferring forces, varying in magnitude and direction between structurally and functionally dissimilar tissues. However, the precise structural and mechanical characteristics underlying the femoral and tibial entheses and their intricate interplay remain elusive. In this study, two thin-graduated mineralization regions in the femoral enthesis (~21 μm) and tibial enthesis (~14 μm) are identified, both exhibiting distinct biomolecular compositions and mineral assembly patterns. Notably, the femoral enthesis interface exhibits progressively maturing hydroxyapatites, whereas the mineral at the tibial enthesis interface region transitions from amorphous calcium phosphate to hydroxyapatites with increasing crystallinity. Proteomics results reveal that Matrix Gla protein uniquely enriched at the tibial enthesis interface, may stabilize amorphous calcium phosphate, while C-type lectin domain containing 11 A, enriched at the femoral enthesis interface, could facilitate the interface mineralization. Moreover, the finite element analysis indicates that the femoral enthesis model exhibited higher resistance to shearing, whereas the tibial enthesis model contributes to tensile resistance, suggesting that the discrepancy in biomolecular expression and the corresponding mineral assembly heterogeneities collectively contribute to the superior mechanical properties of both the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis models. These findings provide novel perspectives on the structure-function relationships of anterior cruciate ligament entheses, paving the way for improved management of anterior cruciate ligament injury and regeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The enthesis as a critical component facilitating force transduction between ligament/tendon and bone, is a complex structure adapted for elimination of stress concentrators1,2. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) serves as a mechanical stabilizer within the knee joint, linking the femur to the tibia via the ACL femoral and tibial entheses3. Despite the prevalence of ACL injuries4, ligament ruptures occur more frequently than enthesis failures5. The limited capacity for natural ACL often necessitates surgical intervention. However, the intricate reconstruction of the ACL-bone interface presents challenges, affecting the graft’s durability and knee function over time6,7. Despite the potential risk of stress concentration and subsequent fracture at the interface between soft and hard materials8, the femoral and tibial entheses demonstrate significant adaptability in response to combined tension, shear, and torsional forces, with the femoral enthesis experiencing considerably more shear stress than the tibial enthesis2,9. This resilience can be attributed to the multi-scale toughening mechanism of extracellular matrix (ECM) present in natural materials10,11,12,13. Thus, analyzing the interplay between organic and inorganic structural components at the ACL-bone interface offers valuable insights into its mechanical conduction mechanisms.

Recent studies have extensively focused on the structural components of the ECM at the tendon/ligament-bone interface11,14,15,16,17,18,19. This interface exhibits complex transitions from tendon/ligament to fibrocartilage and subsequently to subchondral bone20,21. The fibrocartilage zone is further divided into nonmineralized fibrocartilage (NFC) and mineralized fibrocartilage (MFC) regions22. The gradual increment in mineral contents across the gradient mineralized structure is crucial, as it results in a substantial increase in tissue modulus without inducing stress concentration13,23,24,25,26. Despite the utilization of various micro-nano analytical techniques to investigate the nanoscale structure and composition of bone, ligament, and tendon27,28,29,30, knowledge of the multi-scale structure assembly of the graduated mineralized interface is limited31,32. Consequently, further research is required to elucidate the multiscale composition and assembly of the graduated mineral, as well as the precise biomolecular composition and stiffness transition of the interface tissue. These findings will lay the groundwork for designing soft-to-hard interfaces and determining parameters for current ACL-bone regeneration and repair techniques33,34.

In this study, we employed multiple advanced techniques (Fig. S1), including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), high-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM), focused ion beam-SEM (FIB-SEM), Raman spectroscopy, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), selective electron diffraction (SAED), energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), nanoindentation, and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), to examine the location-specific graduated mineral composition and assembly, and mechanical transitions of the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis in human knee joints.

Results

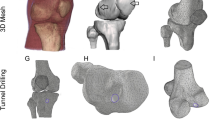

Structural transition of the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces

Healthy human ACL femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis tissues were collected (Figs. 1A and S2A) and identified via histological staining (Figs. 1C and S2B). High-resolution micro-CT and SEM were then employed to examine the microstructures and visualize the macroscale interlocking structures of interfacial tissues. Remarkably, the interfaces in both femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples displayed a complex morphological landscape spanning the critical interface regions, rather than a simple planar structure. This finding is consistent with observations of the supraspinatus tendon-to-bone insertion in mice, suggesting that the interface roughness may contribute to increased toughness at the ligament-to-bone insertion site (Figs. 1B, S3 and movie S1)2,35,36,37. Density-dependent color SEM (DDC-SEM) depicted the mineralization alterations at the interface, between NFC regions (green) and highly mineralized regions (red) (Figs. 1D, and S4)12,38. Moreover, the specific partially mineralized regions of the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces were identified by employing energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) line scanning and surface scanning with the femoral side exhibiting a wider graduated mineralization interface compared to the tibial side (Figs. 1E, F, and S5). The exponential increment curve of Ca and P content in the femoral enthesis interface region yielded a thin region measuring 21.11 ± 2.59 μm and 14.56 ± 3.19 μm in the wave crest and trough region, respectively. In contrast, the tibial enthesis interface region showed thinner regions measuring 13.84 ± 3.41 μm and 6.77 ± 1.70 μm in the crest and trough regions, respectively. The results demonstrated a seamless transition from NFC to highly mineralized regions at both interfaces38, implying the intricate structural adaptations that facilitate efficient force transmission and dissipation at the entheses.

A Schematic and magnetic resonance imaging illustration of the human knee showing the femur-ACL-tibia complex. B Reconstructed 3D volumetric representation of the structures including ligament, ACL-bone interface and subchondral bone tissues (left panel), after threshold-based segmentation with unmineralized ligament digitally removed (right). The micrographs were colored in postprocessing by Amira 2020. C Safranin O/Fast Green (SO) staining images showing histological features of different samples (FE and TE). D DDC-SEM micrographs of FE and TE interface tissues presenting gradual mineral distributions with distinct morphologies. The micrographs were colored in post-processing by combining images obtained from backscatter electron and secondary detectors (red: mineral, green: organic extracellular matrix; original images and processing details are provided in Fig. S4). E SEM images and the corresponding EDX line scan (Ca and P) (down) identifying the FE and TE interface (n = 7/group from the same donor). Data are presented as mean ± SD. (F) A schematic diagram of the interface shape between NFC and MFC in (D) (top panel). The thickness of the two mineralized interfaces quantified by EDX line scan in (D) (bottom panel, n = 12 from 4 donors/group). Each biological replicate is color-coded (orange, green, purple, and yellow), and the technical replicate values were separately pooled for each biological replicate and the mean calculated for each pool; those four means were then used to calculate the average (horizontal bar), standard deviation of the mean (error bars), and P value. Scale bar: (B) 30 μm; (C) 200 μm; (D) 5 μm. *P < 0.05, F (F (3, 12) = 43.215, P < 0.0001; femoral crest versus femoral trough, P = 0.001; tibial crest versus tibial trough, P = 0.001; femoral crest versus tibial crest, P < 0.0001; femoral trough versus tibial trough, P < 0.0001; femoral trough versus tibial crest, P = 0.937), One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Abbreviations, ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; FE, ACL-femoral enthesis; TE, ACL-tibial enthesis; L, ligament; NFC, nonmineralized fibrocartilage; MFC, mineralized fibrocartilage. SB, subchondral bone. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Mechanical performance of the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces

Interestingly, the rough mineralized interface at the ligament-to-bone insertion site has been shown to contribute to enhanced toughness, with the thickness of the interface playing a critical role in determining mechanical properties35,39. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the mechanical performance of the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces, we conducted a thorough evaluation using nanoindentation tests40,41. As a result, a substantial increase in tissue modulus at both interfaces were observed. The tissue modulus of the femoral enthesis sample increased from 40 ± 5 MPa to 760 ± 40 MPa over a ~20 μm thickness interface, whereas the tibial enthesis sample increased exponentially from 27 ± 5 MPa to 1262 ± 218 MPa over a ~10 μm thickness interface (Figs. 2A–C, and S6). The modulus change of both interfaces can be fit with an exponential function, which could produce an efficient mechanical transfer without causing damage12. Comparing the nanoindentation results of femoral enthesis and TE, we found a statistically significant decrease in the modulus of zone-i and an increase in the modulus of zone-iii in tibial enthesis samples (Fig. S7A). Furthermore, the energy dissipation, calculated from the area enclosed by the loading-unloading curves of the nanoindentation test (Fig. S7B)42, was significantly higher in zone-i of the tibial enthesis sample compared to the femoral enthesis sample (Fig. S7C), suggesting that the observed increase in tissue modulus is not solely a function of structural changes but also closely related to alterations in mineral content across the interface regions43. Although the elastic modulus for subchondral bone was found to be lower than previous studies, likely due to the medium stiffness of the probe used to accommodate soft-hard interface tissues, the data obtained from femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces under the same condition offered valuable insights into their distinct mechanical characteristics18,43. To further explore the nanoscale mechanical properties, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was employed to examine the low (i), medium (ii), and highly mineralized (iii) regions of femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples (Fig. 2D–F)44. As anticipated, the distribution of tissue stiffness in zone-i of the femoral enthesis samples exhibited greater variation than that of the corresponding regions in the tibial enthesis samples. Notably, the medium mineralized region (zone-ii) of the tibial enthesis sample displayed a distinctive stiffness peak of 1.82 GPa, which can be ascribed to the narrower mineralization gradient region in tibial enthesis and the inclusion of zone-iii within the scanned area. These distinct stiffness distributions in each mineralized zone were consistent with the microstructures depicted in Fig. 1.

A Schematic view of nanoindentation test for FE and TE. B Average elastic modulus of FE and TE tissues as a function of distance from ligament. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 5/group from the same donor. C Elastic modulus maps of the rectangular area in (A) (resolution: 1 μm in x-axis and 2 μm in y-axis). D Schematic diagram showing the test of nanomechanical response interface regions from the less mineralized region (zone-i) to the intermediate mineralized region (zone-ii), and to the highly mineralized region (zone-iii) using AFM (0.16 × 0.16 μm step). E Consecutive AFM stiffness maps of selected regions in D (zone-i, ii and iii) at interface tissues for both samples. F Corresponding stiffness distributions across calcified cartilage tissues for different samples. G Stress distribution under the tension condition (strain = 7%) in different directions (0°, 30°, 60°, and 90°) for FE and TE models, obtained from FEA. H The max von Mises stress on FE and TE models under different tension conditions (strain = 3%, 5%, and 7%) in different directions (0°, 30°, 60°, and 90°). The FE model exhibits enhanced shear resistance (0o), while the TE model demonstrates greater tensile resistance (90o). Scale bar in (E): 1 μm. Abbreviations, L, ligament; B, bone; FE, ACL-femoral enthesis; TE, ACL-tibial enthesis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

It is important to note that the microscopical and macroscopical structures of the entheses differ based on their anatomical location to fulfill their specific functional demands45,46. Previous studies have reported significant differences in the angle of attachment to the femur and tibia, with the femoral attachment angle being considerably more acute than the tibial attachment angle, resulting in the femoral enthesis being subjected to considerably more shear stress2,9,36. Additionally, finite element analysis (FEA) was utilized to further validate the mechanical superiority of both models based on factors comprising insertion depth, structure, and mechanical gradient alteration in femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis47. The femoral enthesis model exhibited enhanced shear resistance, whereas the tibial enthesis model manifested greater tensile resistance. Specifically, the maximum force value of femoral enthesis was lower than that of tibial enthesis in the force direction of 0°, whereas the maximum force value of femoral enthesis exceeded that of tibial enthesis in the force direction of 90° (Figs. 2G, H, and movie S2).

Multiscale mineral polymorphs transformations at the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces

Spatial gradients in mineral distribution have been shown to play unique roles in mitigating stress concentration during joint movement25,48. This prompted us to analyze the multiscale mineral transformations at the interfaces of femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis using HAADF-STEM and FIB-SEM (Figs. 3 and S8). Noteworthily, both femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples exhibited distinct graduated areas of mineralization, with the femoral enthesis presenting substantially denser mineralization (Fig. 3), corroborated by SEM, EDX-line scan, and TEM images (Figs. 1D, E, and S8). HAADF-STEM and FIB-SEM images of the femoral enthesis sample uncovered three distinct mineral morphologies: loosely fibrous particles and well-defined particles that expanded and fused into platelets, ultimately forming compact aggregates. In contrast, the tibial enthesis sample exhibited three typical mineral forms at the interface: sparsely distributed small ellipsoids that progressively fused into a bulk structure, resulting in dense packing (Figs. 3B–D, and S8). In the mineralization front region (zones-i and ii), the mineral in the femoral enthesis sample had a larger aspect ratio and denser distribution, whilst those in the tibial enthesis sample had an aspect ratio closer to 1 (Fig. 3E–G). Several studies have documented that the incorporation of micro- or nano-particles can effectively improve the stiffness or Young’s modulus49,50. It is worthwhile to highlight that experimental and atomic simulation studies have evinced that the elastic properties of nanoscale materials are dependent on their size51,52,53. The graduated distribution of mineral aggregates at the interface facilitates the adhesion of dissimilar tissues33, and the mineral in the femoral enthesis sample with larger aspect ratios may exhibit an increase in tensile adhesive energy54, thereby effectively anchoring the ACL to the femur under multidirectional stresses.

A FIB-SEM images illustrating the progression of morphologies, distributions and assemblies of mineral particles at the FE and TE interfaces. B Corresponding enlarged BSE images at different sites in (A) showing multiple mineral particles with various morphologies dispersed in the matrix. C 3D rendering of typical mineral particles intersecting with FIB-SEM image planes at the mineralization front of the interface region, demonstrating the mineral appearance and aspect ratio in different samples. D 3D rendering of the mineralization front highlighting distinct mineral assembling patterns for FE and TE. Labeled (colored) mineral tesselles in relation to aspect ratio (unmineralized collagen digitally removed, right panel). E, F Distribution of mineral tesselle sizes generated from label analysis in FE and TE mineralization front obtained from right panel in (D). G The aspect ratio of mineral tesselles in FE and TE mineralization front (n = 64 from 3 donors/group). Each biological replicate is color-coded (orange, green, and purple), and the technical replicate values were separately pooled for each biological replicate and the mean calculated for each pool; those three means were then used to calculate the average (horizontal bar), standard deviation of the mean (error bars), and P value. Scale bar in (A): 2 μm; (D): 1 μm; (B, C, E, F): 200 nm. *P < 0.05, G (P < 0.0001), unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Abbreviations, FE, ACL-femoral enthesis; TE, ACL-tibial enthesis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Compositional analyzes of mineral at the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces

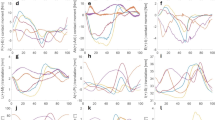

In addition to the gradient structures, the grading of local components serves as another central material motif of the interface tissue25. The diverse mineral morphologies observed in femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces necessitated a comprehensive compositional analysis. Herein, a high-resolution examination of mineral composition and spatial distribution at both the microscale and nanoscale was conducted. Raman spectroscopy was employed to assess the organic and mineral phase at the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces, which revealed the presence of amide III, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), lipids, and amide I peaks in the organic vibrational range (Fig. S9)55,56. In the mineral range, carbonated HAps with PO43- v1 symmetric stretching at 960 cm−1 and a weak planar vibration of CO32- v1 peak at 1071 cm−1 were identified in both femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces (Fig. 4A)57,58. More importantly, a contralateral stretch at 957 cm−1 was detected in the mineral located in the front region of the tibial enthesis interface (Fig. 4A), indicative of the coexistence of HAp precursors and HAps, as further validated by stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy. SRS spectra exhibited a peak at 950 cm-1, corresponding to amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) in the initial region of the tibial enthesis interface. SRS imaging depicted the distribution of ACP and HAps at the tibial enthesis interface, whereas no ACP was observed at the femoral enthesis interface, which was further validated by cryo-TEM (Fig. 4B, S10, and S11)57,58,59. The configuration and position of PO43− at 960 cm−1 and CO32− band at 1071 cm−1 provided significant insights into mineral crystallinity, component proportions, and ionic substitutions. Composition maps of HAp and matrix were generated to elucidate their spatial distribution across both interfaces, giving a gradual increase in HAps content and alternate carbonate content, with wider regions of graduated MFC at the femoral enthesis interface compared to the tibial enthesis interface (Fig. S12A and B). Conversely, a reverse trend was observed in the CO32−/PO43− ratio (Fig. S12C). Further analysis of the interface divided it into four distinct regions (Fig. S8), involved a meticulous elemental analysis of mineral in each region (Fig. S13). Our findings implied a significant increment in calcium, phosphorus, and oxygen content, accompanied by a decrease in carbon content, signifying an enhanced level of mineralization60.

A Raman spectra of the FE and TE interfaces from ligament to subchondral bone in mineral vibrational ranges. B Spectroscopic fingerprint SRS imaging of FE and TE samples showing ACP at 950 cm−1 and HAp at 960 cm−1 by LASSO unmixing. Scale bar in (B): 5 μm. Abbreviations, FE, ACL-femoral enthesis; TE, ACL-tibial enthesis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Overall, the results of this study exposed a depth-dependent distribution of carbonate-substituted HAp at both the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces, with a wider interface observed in femoral enthesis samples compared to tibial enthesis samples, as well as a transformation of ACP to HAp in tibial enthesis samples. While ACP is not known to exist in bone, it is an essential component of tooth enamel, playing a pivotal role in enhancing the enamel’s protective qualities by regulating its solubility, increasing hardness, and improving acid resistance13,61. The presence of ACP confers increased crack resistance59, potentially explain the higher structural integrity of TE. These findings underscore micro-scale spatial gradations in mineral composition and crystallinity at the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces.

Crystallographic features and chemical analysis of mineral polymorphs at the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces

The patterns of mineral assembly at the nanoscale at the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces were analyzed using HRTEM and SAED techniques (Fig. 5A). HRTEM images distinctly exhibited an increase in the crystallinity of particles present at both femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces (i–iv). In the femoral enthesis samples, the crystallization area initially appeared as an elongated 10 nm strip with poor crystalline diffraction, eventually fusing. Conversely, the tibial enthesis samples showed a transition from amorphous, spherical particles with the amorphous scatter of diffuse rings (ACP) to particles approximately 10 nm long ((201) and (211) plane) and finally to highly mineralized polycrystalline particles ((002), (102), (201) and (211) plane) (Fig. 5A). Mineral crystals in the femoral enthesis samples were larger, had a higher aspect ratio, and displayed greater crystallinity, compared to those in the tibial enthesis samples. These findings conjointly unveiled the nanoscale heterogeneity in the assembly modes of HAp at the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces, which may enhance force transmission by effectively dissipating energy at the interface10.

A Corresponding HRTEM and SAED images, collected from zone i-iv in Fig. S8, showing differences in mineral assemblies and their crystallinities of mineral particles at the FE and TE samples. B EELS spectra, acquired at the phosphorus L2,3 edge, carbon K edge, calcium L2,3 edge, nitrogen K edge and oxygen K edge, showing differences in the nanoscale chemical environment of mineral particles (i-iv) in (C). C HHADF-STEM images and corresponding composition maps, collected at the calcium L2,3 edge, nitrogen K edge and oxygen K edge, illustrating the spatial distribution of these elements within the mineral particles from different zones (i-iv) in Fig. S8. (red: nitrogen K edge, green: oxygen K edge, blue: calcium L2,3; The original images and processing details are provided in Fig. S14). Scale bar in (A, HRTEM images): 10 nm; (A, SAED): 5 1 /nm; (C): 10 nm. Abbreviations, FE, ACL-femoral enthesis; TE, ACL-tibial enthesis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

EELS was applied to elucidate the nanoscale chemical environment of various minerals at both femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces (Figs. 5B, C, and SI Table 1). The analysis determined variations in the content of P (L2,3 edges), C (K edges), Ca (L2,3 edges), N (K edge), and O (K edges) in each particle, consistent with the results of EDX (Figs. S13 and S14). Bone carbonate content plays a pivotal role in regulating HAp formation, assembly mode, and morphology62. It is worthwhile emphasizing that the C (K-edge) spectra of all particles in the femoral enthesis sample exhibited four characteristic peaks, whereas in the tibial enthesis sample, carbonyl (peak F) chiefly appeared in particles i-ii, while particles iii-iv exhibited a higher intensity of carbonate (peak G). EELS maps illustrating the localization of the N, O, and Ca signals are delineated in Figs. 5C and S14. The nitrogen signal was found to be co-localized with the mineral or originate from diffuse “cloudy” structures surrounding the mineral, likely representing the organic ECM component. The coexistence of nitrogen and carbonyl peaks within the granules may be attributed to the presence of proteins during the early stage of mineralization63.

Biomolecular Composition of femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis Interfaces

In addition to the transformation of micro/nanostructures and mineral heterogeneity at the nanoscale, the distinctive structural and functional characteristics of the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces are also defined by variations in biomolecules from a molecular standpoint. Thus, LC-MS/MS was employed to identify proteins abundant at the interface (Figs. 6, and S15). The results demonstrated that 59 proteins and four proteins were abundantly expressed in femoral enthesis compared with the ligament and bone, respectively (Fig. 6B, C). On the other hand, 11 proteins and 19 proteins were highly expressed in the tibial enthesis of tibial samples compared to the ligament and bone, respectively (Fig. 6D, E). Taken together, our findings indicate that the protein expression patterns of femoral enthesis are more analogous to those of bone tissues, and those of tibial enthesis tissues are more akin to those of ligament tissues. Nonetheless, these results may have been impacted by incomplete extraction owing to the ultra-thin nature of the interface tissue, potentially compromising protein identification.

A Experimental procedure for the proteomic investigation (n = 3 for each tissue). B–E Tests for differential expression of proteins were based on protein-wise linear models and empirical Bayes statistics87. The plots are based on the fold change (log2) and the P-value (-log10) of all proteins identified in (B) proteins from FE and FL; (C) proteins from FE and FB; (D) proteins from TE and TL; (E) proteins from TE and TB. F Immunofluorescence staining of SLC25A1 (cyan) and CLEC11A (magenta) in ACL-femur tissues and SRPX (cyan) and MGP (magenta) in ACL-tibia tissues. Scale bar: 20 μm. Abbreviations, FL, the femoral part of ACL; FE, ACL-femoral enthesis; FB, ACL-femoral subchondral bone; TL, the tibial part of ACL; TE, ACL-tibial enthesis; TB, ACL-tibial subchondral bone.

In accordance with prior investigations, our findings corroborated the elevated expression of collagen type II in both interfaces11,64. Apart from fibril-forming collagens, a substantial presence of alpha-1 type XVI collagen, a member of the fibril-associated collagens with interrupted triple helices (FACIT) subfamily, was observed in both interface regions. The non-collagenous domains of FACIT collagens introduce kinks in the macromolecular structure, potentially contributing to the unique mechanical properties of the entheses65. Moreover, proteins like biglycan (BGN), decorin (DCN), and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) were abundant in both interface tissues, facilitating collagen fiber assembly. Additionally, the identification of small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycans (SLRP), including chondroadherin (CHAD), fibromodulin (FMOD), and lumican (LUM), in both interface tissues highlighted their crucial role in regulating fiber sliding and thus influencing viscoelastic properties66,67.

Interestingly, our analysis revealed that the expression of C-type lectin domain containing 11 A (CLEC11A) and Solute carrier family 25 member 12 (SLC25A12) was significantly upregulated in the femoral enthesis of femoral samples compared to that of ligament tissue (Figs. 6B and S16). Oppositely, the expression of Matrix Gla protein (MGP) and Sushi repeat containing protein X-linked (SRPX) was significantly upregulated in the tibial enthesis of tibial samples relative to the ligament tissue (Figs. 6D and S16). These observations were in agreement with immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 6F). Previous studies have inferred that CLEC11A may play a decisive role in promoting osteogenesis by stimulating the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into mature osteoblasts68, while MGP may serve as a regulatory protein involved in ACP stabilization and HAp crystallization at the interface69, potentially accounting for the lower crystallinity observed in tibial enthesis samples compared to femoral enthesis samples. SLC25A12 and SRPX have been implicated in regulating the conversion of stress to strain in muscle tissues70,71,72,73,74. The significant presence of these proteins at the interfaces of femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis suggested that their potential role in the mechanical responses observed at the junctions. However, an in-depth understanding of the local distribution of these molecules and their molecular interactions with the surrounding collagen matrix and mineral remains to be explored. Further studies, employing gene knockout mouse models could provide valuable insights into the fundamental influence of these substances on the biomechanical aspects of the ligament-bone interface.

Discussion

The intricate biological characteristics of the enthesis have captured the interest of orthopaedics and tissue engineers for many years75. Despite extensive investigations into femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis18,36,76,77, the multi-scale structure assembly of the graduated mineralized interface remains unknown. A recent study using a murine model demonstrated the development of a mineral gradient at the supraspinatus tendon-to-bone insertion shortly after birth, with an increase in the carbonate content of the apatite mineral at the enthesis over time23. Our results revealed the nanoscale spatial gradient of the structural composition alteration of HAps and organic components in the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interface tissues, playing a significant role in energy dissipation78.

Four potential mechanisms of energy dissipation may be involved for mineralized fibers at soft-hard interface of ACL enthesis, including elastic stretching, molecular slippage, mineral/collagen sliding and crystal dissociation42,79. Under tensile loading, interfibrillar and partially intrafibrillar spherical mineral particles may slide with collagen fibres to dissipate energy, thereby reducing stress concentration and cushioning the impact78. Intriguingly, the unstable ACP minerals are found at the tibial enthesis interface, which should be more likely to undergo translocation with molecular bond breaking between ACP-biomolecules under tensile loads80, potentially resulting in greater energy dissipation in zone-i within the tibial enthesis sample as compared to the femoral enthesis sample. Moreover, proteoglycans, situated on or between collagen fibrils at the ACL enthesis, may exert osmotic pressure to counterbalance compression81. Lubricated molecules including lipids and leucine-rich GAGs abundant in interfacial tissues played a key role in regulating fiber sliding65, thus possibly facilitating the shear resistance of femoral enthesis. And with deeper insertion depth, the femoral enthesis interface was more favorable for shear forces transfer than the tibial enthesis interface39. These discoveries indicate that the graduated mineralization identified at femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis serves to minimize stress concentrations and enable load transfer between soft tissue and bone, thereby promoting the secure attachment of mechanically dissimilar tissues16. In particular, the development of mature HAps with a fibrous arrangement may enhance the ability of the femoral enthesis to resist shearing forces, while the conversion from ACP to maturing HAps may confer tensile resistance to the tibial enthesis (Figs. 2–6).

It is well-established that mechanical loading plays a role in enthesis development and affects the crystallinity within the MFC region of the enthesis82,83. Thus, variations in mineral content and crystallinity between femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis may indicate inherent differences in the loads experienced by these tissue regions. Besides, the observed mineralization is mediated by a complex cellular process involving the release of mineralization precursors or inhibitors from tenocytes and hypertrophic chondrocytes84,85. Further investigations are needed to observe the mineral with nanoscale spatial gradients and collagens in situ to understand their interactions and effect on mechanics. Additionally, the concurrent research is needed to investigate the cellular process and mechanical stimuli responsible for maintaining the nanoscale gradient patterns of calcium phosphate. Collectively, this study sheds light on the future design of bioinspired soft-hard interface materials, and tissue engineering approaches that recapitulate the unique properties of the native enthesis, ultimately improving patient outcomes in orthopaedic surgery and sports medicine.

This study investigated, for the first time, the intricate structural and mechanical characteristics of the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis of the human ACL. The femoral enthesis exhibited a higher resistance to shear forces, while the tibial enthesis contributed more to tensile resistance. The graduated mineralization, ranging from ACP to HAp with varying crystallinity, along with the protein expression profiles, collectively contributed to the unique mechanical properties of these interfaces (Fig. 7). These insights into the structure-function relationships at the ACL entheses provide valuable information for the development of advanced strategies for ACL reconstruction and repair.

Methods

Sample preparation

Specimens of the human healthy ACL-femur and ACL-tibia interface were obtained from surgical discards following amputation procedures with the approval from the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2022LSYD0923) and written informed consent was obtained from each donor. The specimens were obtained from 3 males and 1 female (34–39 years of age, 1 non-manual and 3 manual workers) with ACL and without degenerative changes from macroscopic view or knee X-ray. The ACL femoral and tibial attachments were carefully collected after the removal of excess bone and ligaments, which contained ligament, fibrocartilage, and subchondral bone. The tissue was cut into small pieces and later washed with sterile PBS before being stored at -80°C without any further handling or examination. After collection, the samples were cryo-cut into 3 parts with the blade perpendicular to the plane where the footprint was located, one for macroscopically Micro-CT imaging and mechanical test, one for histology (including SO staining and IF staining), and the other for microscopic evaluation (SEM, Cryo-TEM, Raman spectroscopy, HRTEM, SAED, et al.) and proteomics (Fig. S1). All these samples were serial cryo-sectioned to maintain their original structures and compositions.

Micro-CT

To evaluate the microarchitecture of mineralized fibrocartilage, micro-CT (Bruker, Skyscan 1272) was employed. The frozen samples were sliced into approximately 3 mm cubes and then serially fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and immersed in 70% ethanol. Scans were performed with a pixel size of 3 μm. Amira (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Amira 2020) was employed for the purpose of 3D visualization.

Histology

Samples of Normal femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 48 h. Subsequently, decalcification was carried out utilizing a 10% EDTA-2Na (w/v) solution over a duration of 4 weeks. Afterwards, both specimens were dehydrated and then embedded in paraffin. To identify the ligament-bone interface, measuring 7 μm in thickness were created for Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and Safranin O (SO) staining.

SEM and EDX analyzes

Fresh femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples were thawed at ambient temperature, then immersed in a solution containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde, followed by rinsing with a PBS solution. Subsequently, the specimens were cryo-sectioned into slices that were 30 μm thick along the longitudinal orientation of the interfaces. After cryo-sectioning, the slices were washed with DI water to eliminate the OCT, followed by a series of ethanol solutions (20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, 100%, and 100% (v/v)) for 20 minutes each to facilitate dehydration, and finally left to dry in the air. The samples underwent gold-sputtering and were imaged (Zeiss G300). In order to examine the microstructure of MFC, secondary electrons were collected using a 5 kV accelerating voltage. Acquiring the DDC-SEM images involved the utilization of a 10 kV acceleration voltage. The equipment was equipped with an SE2 detector and a backscatter electron detector that captured secondary electrons and backscattered electrons, respectively. Both modes were used to capture the same area, resulting in the acquisition of DDC-SEM images. The green channel was assigned to the in-lens images, while the red channel was assigned to the backscatter images using Image J. Afterward, the two images were concatenated. Additionally, EDX spectra were obtained in the identical areas utilizing both line and mapping modes to conduct further analysis on the elemental compositions.

FIB-SEM

Specimen preparation: Using a scalpel, small slices of femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples were carefully dissected, which contained the regions between nonmineralized to mineralized regions at the ligament-bone interface. Next, the specimens were preserved in a solution of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for the entire night, then stained with a PBS solution containing 2% osmium tetroxide for a duration of 2 h. Following multiple rinses with PBS solution, the specimens underwent dehydration using a sequence of acetone concentrations (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%, and 100%) with each step lasting one hour, except for the 70% concentration which lasted overnight. Ultimately, the specimens were embedded in spur resin. To reveal longitudinal sections of the ligament-bone interfaces, all embedded samples were grounded and then polished using a diamond suspension to enhance surface smoothness for the following FIB-SEM serial imaging.

Data collection: The Leica EM trimmer was used to carefully trim resin blocks until the black tissue surface in the block became visible. In order to visualize the region of interest, a scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher, Teneo VS) equipped with an ultramicrotome within its specimen chamber was employed. This enabled us to precisely trim the resin blocks and simultaneously capture the electron microscopic image of the sample. Once the region of interest was identified, imaging was conducted utilizing dual-beam scanning electron microscopy (Thermo Fisher, FIB Helios G3 UC). The data-gathering process was conducted using the serial surface view mode, with a slice thickness of 6 nm at 30 keV and 0.43 nA current. Afterwards, every consecutive facial image was captured in backscatter mode (BSE) utilizing an ICD detector, with a 2 kV acceleration voltage and a current of 0.2 nA. The resolution of the image store was set to 3072 × 2048 pixels, with a dwell time of 15 μs and a pixel size of 4.25 nm.

Segmentation and processing of images: Image stacks were aligned and then denoised with the anisotropic diffusion function in Amira 2020 (Thermo Fisher). The threshold-based segmentation and volume rendering were performed, and label analysis tools were employed to measure the aspect ratios of mineral tesselles.

TEM, EDX, HAADF-STEM, EELS and SAED analyzes

The samples were immersed in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 24 h, rinsed with a PBS solution, treated with 1% OsO4 stain, dehydrated, and subsequently enclosed in a spur resin. Afterwards, the samples were sliced into thin sections using a Lerca EM UC7 ultratome with a thickness of 100 nm. These sections were then positioned onto copper grids with a mesh size of 200 and analyzed using a Super-X EDX detector-equipped aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (FEI Titan G2 80–200 microscope). The examination was conducted at a voltage of 200 kV. Regions of interest were examined using HAADF-STEM, TEM-EDX, and SAED patterns. Images of EELS spectra were collected in the range of 100–600 eV to investigate the characteristic edges of the elements of interest (P, C, Ca, N, O). Principal component analysis was applied to calibrate, normalize, subtract background, and process each spectrum. Prior to conducting each experiment, the electron probe of the microscope was calibrated with a DCOR plus spherical aberration corrector by utilizing a gold standard sample. The HAADF-STEM image, SAED, and EELS analysis were conducted using Gatan Digital Micrograph software.

Raman spectroscopy and SRS microscopy

Raman spectroscopy with a confocal Raman microscope (LabRAM HR Evolution, Horiba Co., Ltd.) equipped with a 532 nm laser was utilized to measure the chemical components across femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples. An EMCCD detector with a spectral resolution of approximately 1 cm−1 was utilized to collect spectra within the range of 200 to 1900 cm-1. For the point mode, the spectra were acquired with a 5 s dwell time. In the case of Raman mapping, a continuous scan was conducted with a spatial resolution of approximately 1 μm and a dwell time ranging from 0.1–0.5 s. There was no observed deterioration of the sample when using this parameter.

SRS was performed to detect and visualize the ACP and HAps across femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples using a Multimodal Nonlinear Optical Microscopy System (UltraView, Zhendian (Suzhou) Medical Technology Co., Ltd). A hyperspectral scan step size of 0.5 cm−1 was used to collect spectra within the range of 920 ~ 1002 cm−1. For imaging, 400 × 400 pixels (0.52 μm/pixel) are acquired with a 30 μs dwell time. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method was utilized for spectroscopic fingerprint SRS imaging86. Each image represents substances of different spectra.

Processing high-pressure freezing (HPF) samples and cryo-TEM

In order to observe the mineral transformations of femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces in situ, cryo-TEM imaging was performed on a FEI Talos F200C under low dose mode at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The cryo-sectioned samples were dipped into external cryoprotectant (1-hexadecene) and carefully loaded into HPF sample carriers (0.2 mm depth, 16770141 Type A, Leica). The lid (16770142 Type B, Leica) was dipped in 1-hexadecene and placed on top of the sample carrier. And the samples were frozen using a HPF device (Leica EM ICE) and freeze substituted in EM AFS2 (Leica). A mixture of 0.5% glutaraldehyde, 1.5% H2O and 100% acetone were used for freeze substitution. The AFS temperature progression began at −108 °C for 1 h, followed by warming to −90 °C at a rate of 9 °C/h, maintaining −90 °C for 60 h, warming to −60 °C at a rate of 2 °C/h, maintaining −60 °C for 20 h, warming to −30 °C at a rate of 2 °C/h, maintaining −30 °C for 15 h, and finally warming to 0 °C at a rate of 10 °C/h. At this point, the samples were removed from the specimen carriers (at room temperature) and subsequently embedded in Epon resin. Then sample blocks were sliced into 100 nm thickness using Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome cryo-chamber maintaining the specimens under −150 °C and cryo-TEM imaging was conducted (Table S2).

Proteomics

Sample preparation: Cryo-sectioning was used to prepare ligament, interface and subchondral bone tissues from femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples of three donors. It should be mentioned that the difference between interface, ligament and subchondral bone was mostly larger than our results, as the interface samples were not completely differentiated from ligament and subchondral bone due to the absence of labelling. In the tube, a total of six types of tissue were gathered and then sliced into small fragments. After rinsing with PBS, the tissue samples were scraped off the slides and transferred into 0.6 ml centrifuge tubes. Subsequently, 20 μl of enzyme digestion buffer (0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate) was added to each tube. The mixture was then heated at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by the addition of 1 μl of trypsin (1 μg/μl). After shaking and mixing, the samples were incubated at 37°C overnight ( > 12 h). Next, they were subjected to centrifugation at 14000 g for 15 minutes and the resultant supernatant was gathered. The supernatant was then desalted and utilized for peptide concentration determination using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer.

LC-MS/MS analysis: The peptides were dissolved in the liquid chromatography mobile phase A (0.1% (v/v) aqueous solution of formic acid) and subsequently separated utilizing an UltiMate 3000 nanoLC ultra-high performance liquid chromatography apparatus. The self-filling column used in chromatography had dimensions of 25 cm length and 100 μm inner diameter, packed with C18 material of 1.9 μm. The first mobile phase, referred to as A, consisted of an aqueous solution containing 0.1% formic acid. The second mobile phase, referred to as B, consisted of an aqueous solution containing 0.1% formic acid and 98% acetonitrile. Liquid phase gradient settings: 0–3 min, 3% ~ 10% B; 3–40 min, 10% ~ 24% B; 40–52 min, 24% ~ 38% B; 52–56 min, 38% ~ 80% B; 56–60 min, 80% B. The rate of flow was kept constant at 450 nL/min.

After being separated by the UHPLC system, the peptides underwent ionization in the NSI ion source and were subsequently analyzed using the Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer. A voltage of 2.0 kV was applied to the ion source, and the high-resolution Orbitrap was utilized to detect and analyze both the peptide parent ions and their secondary fragments. The initial range for mass spectrometry scanning was established as 400−1200 m/z with a scan resolution of 60,000. Additionally, the Orbitrap scan resolution was set at 15,000. The data acquisition mode employed a data-dependent scanning (DDA) program with a cycle time of 1 s. To fragment the HCD collision cell, a fragmentation energy of 27% was utilized. In order to enhance the efficient utilization of the mass spectrum, the automatic gain control (AGC) was adjusted to 100%, the signal threshold was established at 50,000 ions/s, the maximum injection time was limited to 22 ms, and a dynamic exclusion time of 30 s was implemented for the tandem mass spectrometry scan to prevent redundant scans of the parent ions. FAIMS Pro’s compensation voltage was adjusted to −45 V.

Database search: MaxQuant (v1.6.15.0) was utilized to search the data obtained from secondary mass spectrometry. The database was searched using UniProt Human (20387 sequences). To calculate the false positive rate (FDR) caused by random matching, the inverse library was included. Additionally, the common contamination library was added to eliminate the impact of contaminated proteins on the identification results. The enzyme cut mode was set to Trypsin/P, with a maximum of 2 missed cut sites. The mass error tolerance for the primary parent ion was set to 20 ppm for the First search and 5 ppm for the Main search. The mass error tolerance for the secondary fragment ion was set to 0.02 Da. Fixed modification was assigned to cysteine alkylation, while oxidation of methionine and acetylation of protein N-terminal were considered as variable modifications. The FDR for protein identification and peptide-spectrum match (PSM) identification was established at 1%.

Proteomics data analysis: The DEP R package was used to identify the proteins that showed differential expression87, using PSMs information as input. The data underwent log2-transformation and was normalized using the normalize Between Arrays function. Next, the lmFit function was employed to establish a linear model for every protein. For every protein, the moderated t-statistic of eBayes was computed, and the p-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the positive FDR through the contrasts fit and eBayes functions. Proteins exhibiting differential expression were characterized by a fold change greater than 2 and an adjusted p value below 0.05.

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent analysis was performed to verify protemoics results according to a standard method. Sections with a thickness of 7 μm thick were initially thawed at ambient temperature and rinsed with a PBS solution having a pH of 7.2. Following an overnight thermal antigen retrieval process utilizing a sodium citrate solution (10 mM) at 65 °C, the samples were treated with 5% (wt/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sangon Biotech, China) at ambient temperature for 60 minutes. Next, the femoral enthesis samples were subjected to incubation with various primary antibodies, including SLC25A12 antibody (1:50, 67467-1-Ig, Proteintech) and CLEC11A antibody (1:100, 55019-1-AP, Proteintech). In the same way, the tibial enthesis samples were left to incubate overnight at 4 °C with various primary antibodies, including MGP antibody (1:400, 60055-1-Ig, Proteintech) and SRPX antibody (1 200, 11845-1-AP, Proteintech). Following PBS Tween (0.01% Tween) wash, the samples were left to incubated at room temperature for 90 minutes with the corresponding secondary antibodies (diluted 1:200 in PBS): Alexa Fluor® 488 Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Antibody (Product #A-11008, Invitrogen) and Donkey anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 546® conjugate (Product #A10036, Invitrogen). Following the rinsing process with PBS solution, the samples were mounted using a fluorescent mounting medium in order to facilitate imaging with a Zeiss 880 laser confocal microscope. Image J was used to analyze the obtained images.

Nanoindentation

Fresh femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples were dissected into small pieces about 200 μm-thick along the longitudinal direction of the interfaces and immersed in a PBS solution for further measurement. Nano-indentation tests were performed using a nano-indenter (PIUMA, Optics 11, Amsterdam Netherlands) to investigate indentation behavior. The soft cantilever (radius: 50 μm, stiffness: 178 N/m) was utilized to measure the elastic modulus of tissues at an indentation depth of 3000 nm. A nanoindentation test matrix (step: x and y-2 × 2 μm) was conducted on the samples to analyze the modulus transition of the ACL-femoral and ACL-tibial interfaces. In order to replicate the physiological conditions, all measurements were conducted in a PBS solution.

AFM

To characterize the nanomechanical attributes of femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis samples, AFM was utilized for conducting Force-Displacement (FD) measurements. The Cypher ES AFM (Oxford Instruments Asylum Research, United States) along with Si cantilevers (AC160TS-R3, Olympus, Japan) were employed. With a back angle α of 35°, the spring constant was 26 N/m and the tip radius measured 7 nm. Data was collected for a 40 × 40 array of FD measurements in three distinct regions within a 5 × 5 μm2 area for both femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis cryo-cut samples. The approach speed of the tip was 3 μm/s until a force of 6 μN was attained, after which the tip was retracted at the identical speed. To fit Young’s modulus, the FD data were analyzed assuming a Hertz model with a tapered end.

FEA

To investigate the role of the spatial arrangement of the modulus and insertion depth at the femoral enthesis and tibial enthesis interfaces, we built a finite element model to investigate their advantages (Fig. S17). Geometric modeling: In the part of Abaqus, the stereo model was established according to the dimensions shown below (Fig. S17A). Partition the computational grid: Both parts of the model adopted a hexahedral and tetrahedral mixed mesh, dominated by hexahedrons for mesh partitioning (Fig. S17B). Define material properties: The ligament part was defined as hyperelastic anisotropic structures using the Holzapfel-Gasser-Ogden material model with C10: 1.95, D: 0.00683, K1: 22.627, K2: 471.255, κ: 0.004888. The material properties of the transition zone were defined based on the data curve obtained from nanoindentation experiments; that was, different material properties were assigned to the corresponding elements according to the different central positions of the grid cells (the average coordinate value of the surrounding nodes). The material properties of individual elements were isotropic elastic bodies with a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3 and Young’s modulus varying in the range of 40–760 MPa for femoral enthesis and 27 to 1261 MPa for TE, depending on their locations. Build the assembly and set up interactions: The two parts were assembled according to their relative position, and the interfaces were bonded. Define the boundary conditions: The surface close to subchondral bone was set as the fixed end (Encastre) (Fig. S17C). Apply load: Displacement loads of 0, 30, 60, and 90 degrees were applied to the ligament end (the same percentage, strain = total displacement divided by model original length = 3%, 5%, and 7%) and submitted for calculation (Fig. S17D).

Statistics and reproducibility

The investigators were blinded to group allocation during data collection and analysis. For each figure, unless otherwise indicated, results were replicated in at least three biological replicates. The data were presented as the mean ± SD. Differences between the values were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s post hoc test to make pairwise comparisons between multiple groups and a two-tailed Student’s t-test when only two groups were being compared using SPSS software (I BM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0). A significance level of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The raw LC-MS/MS data have been deposited to the iProX database (http://www.iprox.org) with the iProX accession: IPX0009424000. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code for proteomic analysis is available at https://github.com/arnesmits/DEP87.

References

Evans, E., Benjamin, M. & Pemberton, D. Variations in the amount of calcified tissue at the attachments of the quadriceps tendon and patellar ligament in man. J. Anat. 174, 145–151 (1991).

Suzuki, D. et al. Functional adaptation of the fibrocartilage and bony trabeculae at the attachment sites of the anterior cruciate ligament. Clin. Anat. 33, 988–996 (2019).

Dodds, J. A. & Arnoczky, S. P. Anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament: a blueprint for repair and reconstruction. Arthroscopy 10, 132–139 (1994).

Musahl, V. & Karlsson, J. Anterior cruciate ligament tear. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 2341–2348 (2019).

van der List, J. P., Mintz, D. N. & DiFelice, G. S. The location of anterior cruciate ligament tears: a prevalence study using magnetic resonance imaging. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 5, 232596711770996 (2017).

Senftl, M. et al. Occurrence of inadequate ACL healing after dynamic intraligamentary stabilization and functional outcome—a multicentre case series. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 32, 1265–1274 (2021).

Previ, L. et al. Spontaneous healing of a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament: a case series and literature review. J. EXP ORTOP 10, 11 (2023).

Fang, Y. et al. Dissecting biological and synthetic soft–hard interfaces for tissue-like systems. Chem. Rev. 122, 5233–5276 (2021).

Otsubo, H. et al. The arrangement and the attachment areas of three ACL bundles. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 20, 127–134 (2011).

Tai, K., Dao, M., Suresh, S., Palazoglu, A. & Ortiz, C. Nanoscale heterogeneity promotes energy dissipation in bone. Nat. Mater. 6, 454–462 (2007).

Rossetti, L. et al. The microstructure and micromechanics of the tendon–bone insertion. Nat. Mater. 16, 664–670 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Identification of an ultrathin osteochondral interface tissue with specific nanostructure at the human knee joint. Nano Lett. 22, 2309–2319 (2022).

DeRocher, K. A. et al. Chemical gradients in human enamel crystallites. Nature 583, 66–71 (2020).

Tits, A. et al. Structural and functional heterogeneity of mineralized fibrocartilage at the Achilles tendon-bone insertion. Acta Biomater. 166, 409–418 (2023).

Buss, D. J., Rechav, K., Reznikov, N. & McKee, M. D. Mineral tessellation in mouse enthesis fibrocartilage, Achilles tendon, and Hyp calcifying enthesopathy: a shared 3D mineralization pattern. Bone 174, 116818 (2023).

Genin, G. M. et al. Functional grading of mineral and collagen in the attachment of tendon to bone. Biophys. J. 97, 976–985 (2009).

Qu, D. et al. Micro- and ultrastructural characterization of age-related changes at the anterior cruciate ligament-to-bone insertion. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 3, 2806–2814 (2016).

Moffat, K. L. et al. Characterization of the structure-function relationship at the ligament-to-bone interface. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7947–7952 (2008).

Zhou, Y. et al. Three-dimensional characterization of the microstructure in rabbit patella–patellar tendon interface using propagation phase-contrast synchrotron radiation microtomography. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 25, 1833–1840 (2018).

Siegel, I. M. Injury and repair of the musculoskeletal soft tissues. JAMA 260, 2304 (1988).

Subit, D., Masson, C., Brunet, C. & Chabrand, P. Microstructure of the ligament-to-bone attachment complex in the human knee joint. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 1, 360–367 (2008).

Wei, X. & Messner, K. The postnatal development of the insertions of the medial collateral ligament in the rat knee. Anat. Embryol. 193, 53–59 (1996).

Schwartz, A. G., Pasteris, J. D., Genin, G. M., Daulton, T. L. & Thomopoulos, S. Mineral distributions at the developing tendon enthesis. PLoS ONE 7, e48630 (2012).

Meyers, M. A., McKittrick, J. & Chen, P.-Y. Structural biological materials: critical mechanics-materials connections. Science 339, 773–779 (2013).

Liu, Z., Meyers, M. A., Zhang, Z. & Ritchie, R. O. Functional gradients and heterogeneities in biological materials: Design principles, functions, and bioinspired applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 88, 467–498 (2017).

Woo, S. L.-Y., Gomez, M. A., Seguchi, Y., Endo, C. M. & Akeson, W. H. Measurement of mechanical properties of ligament substance from a bone-ligament-bone preparation. J. Orthop. Res. 1, 22–29 (1983).

Goh, K. L., Listrat, A. & Béchet, D. Hierarchical mechanics of connective tissues: integrating insights from nano to macroscopic studies. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 10, 2464–2507 (2014).

Puetzer, J. L., Ma, T., Sallent, I., Gelmi, A. & Stevens, M. M. Driving hierarchical collagen fiber formation for functional tendon, ligament, and meniscus replacement. Biomaterials 269, 120527 (2020).

Ahn, T. et al. Hierarchical nature of nanoscale porosity in bone revealed by positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy. ACS Nano 15, 4321–4334 (2021).

Reznikov, N., Bilton, M., Lari, L., Stevens, M. M. & Kröger, R. Fractal-like hierarchical organization of bone begins at the nanoscale. Science 360, eaao2189 (2018).

Li, C., Ouyang, L., Armstrong, J. P. K. & Stevens, M. M. Advances in the fabrication of biomaterials for gradient tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 39, 150–164 (2020).

Khanarian, N. T. et al. FTIR-I compositional mapping of the cartilage-to-bone interface as a function of tissue region and age. J. Bone Min. Res. 29, 2643–2652 (2014).

Calejo, I., Costa-Almeida, R., Reis, R. L. & Gomes, M. E. A physiology-inspired multifactorial toolbox in soft-to-hard musculoskeletal interface tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 38, 83–98 (2020).

Spalazzi, J. P., Gallina, J., Fung-Kee-Fung, S. D., Konofagou, E. E. & Lu, H. H. Elastographic imaging of strain distribution in the anterior cruciate ligament and at the ligament–bone insertions. J. Orthop. Res. 24, 2001–2010 (2006).

Hu, Y. et al. Stochastic interdigitation as a toughening mechanism at the interface between tendon and bone. Biophys. J. 108, 431–437 (2015).

Beaulieu, M. L., Carey, G. E., Schlecht, S. H., Wojtys, E. M. & Ashton-Miller, J. A. Quantitative comparison of the microscopic anatomy of the human ACL femoral and tibial entheses. J. Orthop. Res. 33, 1811–1817 (2015).

Deymier-Black, A. C., Pasteris, J. D., Genin, G. M. & Thomopoulos, S. Allometry of the tendon enthesis: mechanisms of load transfer between tendon and bone. J. Biomech. Eng. 137, 111005 (2015).

Qu, D. et al. Compositional mapping of the mature anterior cruciate ligament-to-bone insertion. J. Orthop. Res. 35, 2513–2523 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Rectangle-capped and tilted micropillar array for enhanced anisotropic anti-shearing in biomimetic adhesion. J. R. Soc. Interface 12, 20150090 (2015).

Abraham, A. C. & Haut Donahue, T. L. From meniscus to bone: a quantitative evaluation of structure and function of the human meniscal attachments. Acta Biomater. 9, 6322–6329 (2013).

Armitage, O. E. & Oyen, M. L. Indentation across interfaces between stiff and compliant tissues. Acta Biomater. 56, 36–43 (2017).

Su, Z. et al. Understanding the mechanics of the temporomandibular joint osteochondral interface from micro- and nanoscopic perspectives. Nano Lett. 23, 11702–11709 (2023).

Fratzl, P., Gupta, H. S., Paschalis, E. P. & Roschger, P. Structure and mechanical quality of the collagen–mineral nano-composite in bone. J. Mater. Chem. 14, 2115–2123 (2004).

Deymier, A. C. et al. Micro-mechanical properties of the tendon-to-bone attachment. Acta Biomater. 56, 25–35 (2017).

Silva, C. J. P. et al. Enthesis: not the same in each localisation - a molecular, histological and biomechanical study. Eur. Cells Mater. 44, 43–55 (2022).

Killian, M. L. Growth and mechanobiology of the tendon-bone enthesis. Semin. Cell Developmental Biol. 123, 64–73 (2022).

Zaffagnini, S., Martelli, S. & Acquaroli, F. Computer investigation of ACL orientation during passive range of motion. Computers Biol. Med. 34, 153–163 (2004).

Bar-On, B., Barth, F. G., Fratzl, P. & Politi, Y. Multiscale structural gradients enhance the biomechanical functionality of the spider fang. Nat. Commun. 5, 3894 (2014).

Rose, S. et al. Nanoparticle solutions as adhesives for gels and biological tissues. Nature 505, 382–385 (2013).

Fu, S.-Y., Feng, X.-Q., Lauke, B. & Mai, Y.-W. Effects of particle size, particle/matrix interface adhesion and particle loading on mechanical properties of particulate–polymer composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 39, 933–961 (2008).

Wong, E. W., Sheehan, P. E. & Lieber, C. M. Nanobeam mechanics: elasticity, strength, and toughness of nanorods and nanotubes. Science 277, 1971–1975 (1997).

Zhou, L. G. & Huang, H. Are surfaces elastically softer or stiffer? Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 1940–1942 (2004).

Li, P., Wang, Q. & Shi, S. Differential scheme for the effective elastic properties of nano-particle composites with interface effect. Comput. Mater. Sci. 50, 3230–3237 (2011).

Arno, M. C. et al. Exploiting the role of nanoparticle shape in enhancing hydrogel adhesive and mechanical properties. Nat. Commun. 11, 1420 (2020).

Bonifacio, A. et al. Chemical imaging of articular cartilage sections with Raman mapping, employing uni- and multi-variate methods for data analysis. Analyst 135, 3193 (2010).

Das Gupta, S. et al. Raman microspectroscopic analysis of the tissue-specific composition of the human osteochondral junction in osteoarthritis: A pilot study. Acta Biomater. 106, 145–155 (2020).

Akiva, A. et al. On the pathway of mineral deposition in larval zebrafish caudal fin bone. Bone 75, 192–200 (2015).

Kazanci, M., Fratzl, P., Klaushofer, K. & Paschalis, E. P. Complementary information on in vitro conversion of amorphous (precursor) calcium phosphate to hydroxyapatite from Raman microspectroscopy and wide-angle x-ray scattering. Calcif. Tissue Int 79, 354–359 (2006).

Saber-Samandari, S. & Gross, K. A. Amorphous calcium phosphate offers improved crack resistance: a design feature from nature? Acta Biomater. 7, 4235–4241 (2011).

Gupta, H. S. et al. Two different correlations between nanoindentation modulus and mineral content in the bone–cartilage interface. J. Struct. Biol. 149, 138–148 (2005).

Gordon, L. M. et al. Amorphous intergranular phases control the properties of rodent tooth enamel. Science 347, 746–750 (2015).

Wingender, B. et al. Carbonate substitution significantly affects the structure and mechanics of carbonated apatites. Acta Biomaterialia 122, 377–386 (2021).

Nitiputri, K. et al. Nanoanalytical electron microscopy reveals a sequential mineralization process involving carbonate-containing amorphous precursors. AC Nano 10, 6826–6835 (2016).

Thomopoulos, S., Williams, G., Gimbel, J., Favata, M. & Soslowsky, L. Variation of biomechanical, structural, and compositional properties along the tendon to bone insertion site. J. Orthop. Res. 21, 413–419 (2003).

Mouw, J. K., Ou, G. & Weaver, V. M. Extracellular matrix assembly: a multiscale deconstruction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 771–785 (2014).

Rigozzi, S., Müller, R., Stemmer, A. & Snedeker, J. G. Tendon glycosaminoglycan proteoglycan sidechains promote collagen fibril sliding—AFM observations at the nanoscale. J. Biomech. 46, 813–818 (2013).

Thorpe, C. T., Birch, H. L., Clegg, P. D. & Screen, H. R. C. The role of the non-collagenous matrix in tendon function. Int. J. Exp. Path. 94, 248–259 (2013).

Yue, R., Shen, B. & Morrison, S. J. Clec11a/osteolectin is an osteogenic growth factor that promotes the maintenance of the adult skeleton. Elife 5, e18782 (2016).

Murshed, M. Mechanism of Bone Mineralization. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8, a031229 (2018).

Agudelo, L. Z. et al. Skeletal muscle PGC−1α1 reroutes kynurenine metabolism to increase energy efficiency and fatigue-resistance. Nat. Commun. 10, 2767 (2019).

Housmans, B. A. C. et al. Direct comparison of non-osteoarthritic and osteoarthritic synovial fluid-induced intracellular chondrocyte signaling and phenotype changes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 31, 60–71 (2022).

Maciej-Hulme, M. L., Melrose, J. & Farrugia, B. L. Arthritis and Duchenne muscular dystrophy: the role of chondroitin sulfate and its associated proteoglycans in disease pathology and as a diagnostic marker. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 324, C142–C152 (2022).

An, H., Zheng, H., Zhang, L., Ma, L. & Liu, Z. Partial least squares based identification of Duchenne muscular dystrophy specific genes. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 14, 973–982 (2013).

Martin, K. S., Azzolini, M. & Lira Ruas, J. The kynurenine connection: how exercise shifts muscle tryptophan metabolism and affects energy homeostasis, the immune system, and the brain. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 318, C818–C830 (2020).

Lu, H. H. & Thomopoulos, S. Functional attachment of soft tissues to bone: development, healing, and tissue engineering. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 15, 201–226 (2013).

Zhao, L., Thambyah, A. & Broom, N. D. A multi-scale structural study of the porcine anterior cruciate ligament tibial enthesis. J. Anat. 224, 624–633 (2014).

Zhao, L., Lee, P. V. S., Ackland, D. C., Broom, N. D. & Thambyah, A. Microstructure variations in the soft-hard tissue junction of the human anterior cruciate ligament. Anat. Rec. 300, 1547–1559 (2017).

Jiang, N. et al. Spatial heterogeneity directs energy dissipation in condylar fibrocartilage. Small 19, e2301051 (2023).

Depalle, B., Qin, Z., Shefelbine, S. J. & Buehler, M. J. Large deformation mechanisms, plasticity, and failure of an individual collagen fibril with different mineral content. J. Bone Min. Res. 31, 380–390 (2016).

Uskoković, V. et al. Insights into the kinetics of thermally induced crystallization of amorphous calcium phosphate. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 29221–29235 (2018).

Baer, E., Hiltner, A. & Keith, H. D. Hierarchical structure in polymeric. Mater. Sci. 235, 1015–1022 (1987).

Thomopoulos, S. et al. Decreased muscle loading delays maturation of the tendon enthesis during postnatal development. J. Orthop. Res. 25, 1154–1163 (2007).

Schwartz, A. G., Lipner, J. H., Pasteris, J. D., Genin, G. M. & Thomopoulos, S. Muscle loading is necessary for the formation of a functional tendon enthesis. Bone 55, 44–51 (2013).

Ayoubi, M. et al. 3D interrelationship between osteocyte network and forming mineral during human bone remodeling. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, e2100113 (2021).

Zou, Z. et al. Three-dimensional structural interrelations between cells, extracellular matrix, and mineral in normally mineralizing avian leg tendon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 14102–14109 (2020).

Lin, H. et al. Microsecond fingerprint stimulated Raman spectroscopic imaging by ultrafast tuning and spatial-spectral learning. Nat. Commun. 12, 3052 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Proteome-wide identification of ubiquitin interactions using UbIA-MS. Nat. Protoc. 13, 530–550 (2018).

Sadeqi, S., Summers, R., Erbulut, D. U. & Goel, V. K. Optimization of material coefficients in the holzapfel-gasser-ogden material model for the main four ligaments of the knee joint-A finite element study. Appl. Math. 12, 1166–1188 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (82072512 to X. Dai, 32371411 to X. Wang, T2121004 to H. Ouyang, 12125205 to J. Qian). We thank Xi Zheng from Zhejiang University for SEM imaging and EDX analysis; we thank Chaogang Xing for support in obtaining and analyzing micro-CT data; we thank Jiansheng Guo from the Center of Cryo-Electron Microscopy, Zhejiang University for FIB-SEM imaging; we thank Lingyun Wu from the Center of Cryo-Electron Microscopy, Zhejiang University for cryo-TEM imaging; we thank Shoupu Yi from Zhendian (Suzhou) Medical Technology Co., Ltd for stimulated Raman spectroscopic imaging; and we thank Guoqing Zhu from Zhejiang University for the HRTEM and SAED imaging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.F., X.W., X.D., and H.O. conceived the original ideas and designed the project. Methodology: J.F., H.L., W.Li., Z.P., R. M., Y.Y., C.X., J.L., W.S., R.Li., J.W., J.D., K.Xu., X.Yu., T.Xu., W.D.; J.F., X.W., and X.Y. discussed the results, interpreted the data, and wrote and revised the paper. X.D., H.O. and J.Q. contributed to the manuscript revision and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, J., Wang, X., Lai, H. et al. Decoding the mechanical characteristics of the human anterior cruciate ligament entheses through graduated mineralization interfaces. Nat Commun 15, 9253 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53542-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53542-5

This article is cited by

-

Hierarchically structuralized hydrogels with ligament-like mechanical performance

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Evaluating the impact of contrast agents on micro and nano mechanics of soft-to-hard tissue interface

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

3D full-field lacunar morphology and deformation of calcified fibrocartilage in the loaded Achilles enthesis of a mouse

Communications Materials (2025)

-

Mechano-chemo-biological theory of cells and tissues: review and perspectives

Acta Mechanica Sinica (2025)