Abstract

Symmetry plays an important role in determining the physical properties in condensed matter physics, as the symmetry operations of any physical property must include the symmetry operations of the point group of the crystal. As a consequence, crystallographic polarity and chirality are expected to have an impact on the Cooper pairing in a superconductor. While superconductivity with crystallographic polarity and chirality have both been found in a few crystalline phases separately; however, their coexistence and material realizations have not been studied. Here, by utilizing transport, Raman scattering, and transmission electron microscopy, we unveil a unique realization of superconductivity in single-crystalline Mo3Al2C (superconducting Tc=8 K) with a polar charge-density-wave phase and well-defined crystallographic chirality. We show that the intriguing charge density wave order leads to a noncentrosymmetric-nonpolar to polar transition below T*=155K via breaking both the translational and rotational symmetries. Superconductivity emerges in this polar and chiral crystal structure below Tc=8 K. Our results establish that Mo3Al2C is a superconductor with crystallographic polarity and chirality simultaneously, and motivate future studies of unconventional superconductivity in this category.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of ‘ferroelectric metals’ was first proposed by Anderson and Blount more than half a century ago1. Ferroelectricity and metallicity are conventionally considered incompatible as itinerant electrons tend to screen long-range Coulomb interactions and weaken polar instabilities. This makes the appearance of an inversion-symmetry breaking transition in metals rare, although numerous compounds are predicted to host such transitions2,3,4,5,6,7. Despite these challenges, LiOsO3 and WTe2/MoTe2 are two unambiguous examples of experimentally verified polar metals, driven by polar instability which is decoupled with itinerant electrons at the Fermi level8,9,10 and in-plane interlayer sliding mechanisms11,12, respectively. Another way to generate polarization is via translational symmetry breaking by virtue of a charge-density wave (CDW). When a non-centrosymmetric charge modulation occurs, it could result in a potential net electric polarization13,14,15. Achieving CDW-driven polar metals have particular significance that they can in principle enable ultrafast switching at characteristic electronic rather than lattice time scales16,17.

Since superconductivity (SC) tends to arise from itinerant electrons in a metallic system, the coexistence of ferroelectricity/polarity and SC is unusual and is a topic of active discussions18,19,20,21. Examples of such polar superconductors (existence of a polar axis in a superconductor) are the doped SrTiO3 (Tc less than 1 K)18,19,20, bilayer Td-MoTe2 (Tc = 2.3 K)21, and various heavy fermions superconductors (Tc ~ 1–3 K)22. The presence of a polar axis in a superconductor gives rise to phenomena such as exotic nonreciprocal charge transport23,24,25,26, including the superconducting diode effect27, the mixing of spin-triplet and spin-singlet order parameters, as well as topological SC featuring a Majorana edge state28. On the other hand, superconductors with a chiral structure are reported in Li2Pd3B, Li2Pt3B29,30, Mo3Al2C31, NbRh2B232, and TaRh2B232. Among them, Li2Pt3B has been proposed to be a candidate for chiral SC29.

Superconductors with a polar and chiral crystal structure are expected to have unconventional Cooper paring, as the superconducting order parameter must respect the symmetry of the underlying crystal lattice according to the Neumann’s principle. However, such type of superconductors is rare. Identifying superconductors in this category are important not only for fundamental science in the multiferroic and SC community, but also for technological applications27.

In this work, we present evidence for a new category of superconductor, Mo3Al2C, which exhibits superconducting transition temperature (Tc) of 8 K and possesses both structural polarity and chirality. The polarization is induced by a CDW order that appears below T* = 155 K, characterized by a cubic-nonpolar to rhombohedral-polar phase transition. SC emerges deep within this polar and chiral crystal structure below Tc, establishing Mo3Al2C as a unique superconductor with both structural polarity and chirality.

Results

Crystal structure

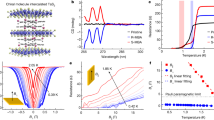

Mo3Al2C has a cubic structure with space group P4132 or its enantiomorphic space group P4332 (point group O) at room temperature (Supplementary Note I). The crystal structure lacks inversion and mirror symmetries. There are four three-fold axes along the body-diagonal directions and three C2 axes perpendicular to a fixed three-fold axis as shown in Fig. 1a. Thus, the structure of Mo3Al2C is noncentrosymmetric, chiral, and nonpolar at room temperature. Upon cooling, as shown in Fig. 1b, resistivity measurement shows that there is a superconducting transition at around Tc = 8 K and bulk SC is confirmed by the magnetic susceptibility measurement (Supplementary Note I). The resistivity measurement also shows a dip at around T * = 155 K33. The anomalies at T * are also found in earlier magnetic susceptibility, specific heat, nuclear-magnetic-resonance (NMR) measurements34,35.

a Crystal structure of Mo3Al2C showing one C3 axis and three C2 axis perpendicular to the three-fold axis. b Resistivity of Mo3Al2C on the (1 0 0) surface recorded in the cooling-down process (blue squares) and warming-up process (red circles). The inset of (b) shows the resistivity around superconducting transition temperature. Raman spectra of Mo3Al2C on a polished (1 0 0) surface in the XX (c), \({X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} }\) (d), and XY (e) scattering geometries at 312 K and 26 K. The black solid lines as well as the red and blue shaded areas are the fitting results. Temperature dependent selected area electron diffraction patterns of Mo3Al2C single crystal along [1 1 0]c/[1 \(\bar{1}\)\(\bar{4}\)]h (f) and [0 0 1]c/[1 \(\bar{1}\) 2]h (g), revealing superlattice Bragg peaks below T*. The subscript c and h denote the cubic and hexagonal notations, respectively.

To understand the resistivity anomaly at T *, we perform Raman scattering measurement from a polished (1 0 0) surface of Mo3Al2C in the XX, \({X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} }\), and XY scattering geometries at 312 K and 26 K. For the XX scattering geometry shown in Fig. 1c, we detect two phonon modes at 180 and 319 cm−1 with Lorentzian lineshape at 312 K and 26 K, and a third phonon mode at around 500 cm−1 that appears only at low temperature. These three A1-symmetry modes are dominated by Mo, Al, and C lattice vibrations, respectively36 (Supplementary Note II). Specifically, the broad peak at around 50 cm−1 appearing at low temperatures is the amplitude mode of the CDW order parameter (see the section of the CDW transition). The peak at 129 cm−1 at 312 K in the XX scattering geometry is a leakage of the T2 phonon from the XY scattering geometry due to imperfect cutting or sample polishing of the single crystal. In the \({X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} }\) scattering geometry, we detect three sharp phonon modes at 164, 245, and 285 cm−1 and a broad mode at 75 cm−1 at 312 K shown in Fig. 1d. They are all E-symmetry phonon modes. The three sharp E modes are first-order phonons, while the broad one is a second-order two-phonon excitation as the linewidth is four times of the three sharp ones. Below T *, the three first-order E-symmetry phonon modes do not split at 26 K. In the XY scattering geometry, we detect two T2-symmetry phonons at 129 and 190 cm−1 at 312 K. They split into two modes in the 26 K data as shown in Fig. 1e, indicating a structural phase transition below T *. Since the T2 phonon splitting is independent of the domain orientations, the presence of domains does not affect the conclusion. By virtue of the correlation table of the point group O of the high-temperature structure (METHODS), based on the fact that E modes do not split while T2 modes split into two modes below T *, we infer that low-temperature structure belongs to a rhombohedral point group C3 or D3.

To reveal the potential ordering vector of the low-temperature structure, we conduct transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurement on Mo3Al2C. Figure 1f, g represent the [1 1 0]c and [0 0 1]c zone-axis selected area electron diffraction patterns taken at 300 K and 85 K, respectively. The data at 300 K [left panels of Fig. 1f, g] are consistent with the primitive P4132 cubic structure (a = 6.8638 Å). The data at 85 K, shown in the right panels of Fig. 1f, g, reveal evidence of a phase transition from the presence of the systematic superlattice Bragg peaks alongside the fundamental Bragg peaks. The appearance of the superlattice reflections (1/2, −1/2, 0) [Fig. 1f] and (1/2, −1/2, 0)/(−1/2, −1/2, 0) [Fig. 1g] while they are absent at half of (0, 0, 1) indicates a transition involving 2 × 2 × 1 supercell in the hexagonal setting. Our results suggest that Mo3Al2C undergoes a transition to a rhombohedral structure below T *, leading to either the nonpolar R32 (point group D3) or the polar R3 (point group C3) space group with lattice vectors (−2, 2, 0), (0, −2, 2), and (1, 1, 1) in relation to those of the cubic unit cell. The lattice constants for the supercell are a ≈ 11.896 Å, α = 109.58∘ in the trigonal setting or a ≈ 19.44 Å, c ≈ 11.83 Å in the hexagonal setting.

Polar domains

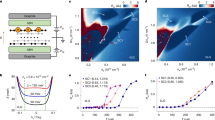

An intriguing question arises: Is the superconductor Mo3Al2C with structural chirality also a polar superconductor? To address this question and probe polar domains in Mo3Al2C, we utilize dark-field transmission electron microscopy (DF-TEM), which is known for its high spatial resolution and ability to isolate distinct types of domains using a specific diffraction spots37. In Fig. 2, we show a series of DF-TEM images taken along the [1 1 0]c or [1 \(\bar{1}\)\(\bar{4}\)]h direction using superlattice peaks (1) \({g}_{1}^{\pm }=\pm {(1/2,-1/2,4)}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) containing the polar contributions along the [1 1 1]c polar axis [Fig. 2a, b], and (2) \({g}_{2}^{\pm }=\pm {(1/2,-1/2,0)}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) containing mainly the information in the plane perpendicular to the [1 1 1]c polar axis [Fig. 2c]. Evident in Fig. 2a, b is the presence of 180∘-type polar domains on a 100-nm scale, showing broken fourfold and two-fold symmetry of the cubic phase, resulting in the polar R3 phase with point group C3. The polar domains with black and white contrasts are associated with the ±[1 1 1]c or ±[001]h polar axes, ~35∘ away from the out-of-plane direction of the images. In addition to the small polar domains, sub-micrometer-sized wavey antiphase boundaries shown as dark lines are resolved [Fig. 2c]. These antiphase boundaries do not exist above T * and exhibit varying features during different cooling cycles, suggesting that domain formation below T * is not simply due to pinning by disorder such as chemical defects or dislocations (Supplementary Note III). These images show that there seems to be no clear interlockings for these two types of domains below T *. Our results reveal a non-polar to polar transition below T * in the superconductor Mo3Al2C.

a Dark-field TEM images were taken at 85 K using \({g}_{1}^{+}={(1/2,-1/2,4)}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) spot along [1 1 0]c. Abundant 180∘ polar domains on the 100 nm scale or less are shown in black and white contrast. Scale bar is 200 nm. b Dark-field-images acquired at the same area using the \({g}_{1}^{-}=-{(1/2,-1/2,4)}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) spot. c Dark-field-images acquired at the same area using the \({g}_{2}^{\pm }=\pm {(1/2,-1/2,0)}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) spots. Red arrows and a white dot loop are added to guide the eye. The reversed contrast between (a) and (b) demonstrates the Friedel’s pair breaking due to the noncentro-symmetrical polar nature, while no contrast change of antiphase domains shown in (c). The average polar domains are on the order of 100 nm, while antiphase domains are about half-micrometer.

CDW transition

To further uncover the nature of phase transition at T *, we study the temperature dependence of the Raman response in the XX and \({X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} }\) scattering geometries. In Fig. 3a, b, we show the Raman response in the XX scattering geometry. Upon cooling to T *, the low-energy electronic continuum below 100 cm−1 builds up gradually in the XX (A1 + E) scattering geometry while the continuum remains unchanged for the \({X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} }\) (E + T1) scattering geometry (Supplementary Note IV), indicating the existence of the A1-type fully-symmetric charge fluctuations. This is a signature of a precursor density-wave order approaching T *, similar to the CDW-compound ErTe338. Below T * as shown in Fig. 3c, the most prominent feature is the redistribution of the low-energy spectra weight: The low-energy continuum intensity below 40 cm−1 is progressively suppressed, while the high-energy continuum intensity in the range between 40 cm−1 and 250 cm−1 is enhanced and a broad peak centered at around 60 cm−1 (labeled as A1) is developed. Such a spectra weight transfer is an evidence for gap opening below T *39. This observation is consistent with gap opening from the previous 27Al NMR studies that the Knight shift and the spin-lattice relaxation rates are significantly reduced below T *35,40. Therefore, the existence of charge fluctuations above T *, the gap opening below T *, and superlattice Bragg peaks appearance below T * all point to a second-order CDW transition at T *. Moreover, as the temperature cools below 100 K, two shoulder peaks at around 68 (labeled as A2) and 90 cm−1 (labeled as A3) become noticeable and gain intensity on top of the A1 peak.

a The colorplot of the T-dependence of Raman spectra in XX [A1 + E] scattering geometry. b T-dependence of Raman spectra for T > T * corresponding to (a). c Same as (b) but for T < T *. d The colorplot of the T-dependence of Raman spectra in \({X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} }\) [E + T1] scattering geometry. e T-dependence of Raman spectra corresponding to (d). Spectra are vertically shifted for better visualizations. f, g, h T-dependence of peak frequency, half-width-at-half maximum (HWHM), and integrated area for the A1, A2, A3, and E1 modes marked in (c) and (e). Error bars represent the standard deviation.

In Fig. 3d, e, we show the Raman response in the \({X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} }\)(E + T1) scattering geometry. In addition to the three fundamental E modes at 164, 245, and 285 cm−1 which persists upon cooling from 312 K to 26 K, several new E-symmetry modes between 140 cm−1 and 220 cm−1 appear below T *. Notably, the two-phonon excitation feature (labeled as E1) softens a bit upon cooling to T *.

In Fig. 3f–h, we present the temperature dependence of the mode energy, half-width-at-half maximum (HWHM), and the integrated area for the A1, A2, A3, and E1 modes. The A1 mode frequency increases from 48 to 60 cm−1 while A2 and A3 modes barely change upon cooling below T *. In contrast, the E1 mode softens from 75 cm−1 at 312 K to 70 cm−1 at T *. The HWHM for the A1 mode decreases by a factor of three, while A2 and A3 modes barely change upon cooling. The integrated area for the A1 mode increases gradually below T *, reaching four times of its value at T * when cooled to the lowest temperature, while the A2 and A3 modes’ integrated area increase moderately below T *. The differences in the temperature dependence between A1, A2, and A3 peaks suggest that the A1 peak represents the CDW amplitude mode while A2 and A3 peaks correspond to the folded phonon modes41,42.

Upon cooling below Tc, the phononic features barely change, namely, the amplitude mode A1 and folded phonon modes A2 and A3 remain the same (Supplementary Note V). This indicates that the CDW order coexists with SC. Furthermore, since Raman scattering is exceptionally sensitive to the subtle breaking of crystalline symmetry39,43, the persistence of the same phononic features above and below Tc indicates that the point group symmetry (C3) persists also in the SC state. Thus, the SC state of Mo3Al2C is both chiral and polar.

Discussions

Origin of the CDW transition

We now discuss the origin of the CDW transition at T * in Mo3Al2C. Based on the density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Supplementary Note VI), there are three unstable modes in the phonon dispersion for the cubic phase of Mo3Al2C: Γ4(0, 0, 0), M5(0.5, 0.5, 0), and X2(0.5, 0.5, 0), consistent with ref. 36. The Γ4 instability leads to a R3 structure without translational-symmetry breaking, and hence the same unit-cell volume. The only structure with 3-fold rotational symmetry that the X2 instability can lead to is a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell with eight times the volume of the primitive cell (Supplementary Note VII). On the other hand, the M5 instability can lead to the R3 structure with the correct translational symmetry breaking and 4 times the volume of the primitive cell. Thus, the only way to get a CDW structure below T * commensurate with 2 × 2 × 1 supercell in the hexagonal setting and 3-fold rotational symmetry in the R3 phase is to have a M5 lattice instability at the Brillouin zone boundary. The observed softening of the second-order E1 mode above T * [Fig. 3f] suggests the softening phonon branch at around M points, similar to the study of 2H-NbSe241.

Origin of the polarization

The origin of the polarization in Mo3Al2C poses new questions. Since the crystal structure is already noncentrosymmetric above T *, the transition to the polar structure is not a simple off-centering of atoms, but rather roots in the breaking of the two-fold rotational symmetries perpendicular to the polar axis in the symmetry group of the re-arranged atoms below T * [Fig. 1a]. It can nevertheless be either due to a zone-center instability that breaks the symmetry (proper ferroelectricity), or a zone-boundary instability that breaks translational symmetry in addition to the rotational symmetry (improper ferroelectricity). In the former case, another important question arises about whether the transition is a displacive or an order-disorder type transition.

The order-disorder mechanism was discussed for the case of LiOsO344,45. One of the key evidence in support of this mechanism in LiOsO3 is the sharp drop in resistivity below the polar transition. The large resistivity above the transition is attributed to the incoherent charge transport induced by the disordered Li off-center displacements8. For Mo3Al2C, this mechanism for the nonpolar-to-polar transition is less likely, because the temperature dependence of the resistivity is almost flat from 300 K down to 8 K for single crystals [Fig. 1b]33 as well as polycrystalline samples46. While some amount of disorders or vacancies could be present in the Mo3Al2C sample33, the flat resistivity curve suggests that the scattering rates for the electrons barely change upon cooling through the transition, which rules out disorders near the transition, and hence an order-disorder mechanism.

Our DFT lattice dynamics calculations, as well as earlier report36, indicate that there are both zone-center and zone-boundary instabilities, which makes both proper and improper instabilities possible. The unstable Γ mode transforms as the Γ4 irreducible representation. It is infrared-active and a polar instability. Thus, the zone-center Γ4 mode leading to the polarization while a zone-boundary M5 mode leading to the CDW order is seemingly possible. However, this scenario is inconsistent with the observation that there is only a single transition at T *. It is also not possible for the CDW order being a secondary and improper order parameter that condenses only due to the nonzero amplitude of the polar mode, because the CDW order breaks the translational symmetry, which by definition cannot be broken by a zone-center Γ polar mode.

This may lead us to conclude that the polarization is induced by an improper mechanism, where a zone-boundary M5 mode couples with a zone-center Γ4 polar mode, and leads to a nonzero magnitude of the polarization below T *. The details of this coupling can be understood by building a Landau free-energy expansion for the high-temperature cubic structure via the trilinear coupling between the M5 and the polarization P along the [1 1 1] pseudo-cubic direction (Supplementary Note VIII). When the M5 mode condenses, this leads to a first-order term in P to appear in the free energy expansion, which necessarily leads to a nonzero value of P (Supplementary Note VIII).

We note that the density of states at the Fermi level are dominated by Mo 4d electronic states from the DFT band structure calculations31. In contrast, the Al and C electronic states are negligibly small between −2 eV and 2 eV, and they get a bit larger below −2 eV31. Furthermore, from the DFT phonon calculations36, the phonon density of states below 100 cm−1 are dominated by Mo lattice vibration modes, while they are dominated by C lattice vibration modes above 500 cm−1. In between 100 cm−1 and 500 cm−1, they are dominated by Mo and Al lattice vibration modes. In the Raman spectra shown in Fig. 1c–e, we detect substantial mode intensity for the new Mo modes (A1, A2, and A3) below 100 cm−1 and new C modes at around 500 cm−1 in the XX scattering geometry, while those new E-symmetry modes involving the Al lattice vibration in-between 100 cm−1 and 350 cm−1 in the \({X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} }\) scattering geometry are five times weaker. This indicates that Mo and C atoms are mainly involved in the polar distortions below T *. We note that previous 27Al NMR studies revealed the broadening of Al spectrum below T * and associated it to the gradual distortions near the Al sites toward a lower symmetric structure40. To resolve the lattice distortions below T *, we have performed the single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurement of Mo3Al2C at 300 K and 100 K. We failed to detect the superlattice Bragg peaks in the diffraction patterns (Supplementary Note X). Regardless of the origin for the polarization below T *–proper or improper mechanism, substantial C-lattice contributions to the polar distortion, which are decoupled from the itinerant Mo 4d electronic states around the Fermi level, help to stabilize the polar metal phase of Mo3Al2C according to the decoupled electron mechanism2,9,10

SC state

Finally, we discuss the symmetry and the properties of the SC state in Mo3Al2C. The point group symmetry of Mo3Al2C in the SC state is C3. It contains two irreducible representations A and E. The A-symmetry SC order parameter preserves the three-fold rotational symmetry and the SC gap could be isotropic or anisotropic. The E-symmetry SC order parameter breaks the three-fold rotational symmetry and is a two-component order parameter. The lack of inversion symmetry in the low-crystallographic-symmetry Mo3Al2C necessarily leads to the mixing of singlet and triplet SC order parameters, thus creating an unconventional SC state. Previous studies have reported that Mo3Al2C has a s-wave-like nodeless gap33,34,46,47. However, a recent muon spin relaxation/rotation (μSR) study revealed that the ratio \({T}_{c}/{\lambda }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{-2}\) (λeff is the effective London penetration depth) is comparable to the class of unconventional superconductors in the Uemura plot, which points towards an unconventional pairing mechanism in the isostructural compound W3Al2C48. The study of the relationship between the polar structure and the symmetry of the superconducting order parameters in Mo3Al2C is beyond the scope of this current work but will motivate future studies.

In summary, we identify Mo3Al2C as a new category of superconductor with structural polarity and chirality. Our results open up an avenue to discover more CDW-driven polarization in noncentrosymmetric metals as well as polar superconductors. Materials in this category could have new physical properties and applications, motivating future studies of switchable ferroelectric SC21, nonreciprocal charge transport24,27, and unconventional paring mechanism28,49.

Methods

Single crystal preparation and characterization

Mo3Al2C single crystals were grown using a slow cooling method in a sealed alumina tube. Powders of Mo : Al : C in molar ratio 3 : 4 : 1 were mixed and pre-reacted in a sealed vacuum quartz tube at 1000 °C for 5 h. The product was filled into an one-end-closed alumina tube. Then, the open end was sealed in a laser floating zone furnace in an Argon flow. The sealed alumina tube was heated to 1650 °C, kept for 5 h, 5 °C/h cooled to 1250 °C, then 100 °C/h cooled to room temperature. Millimeter size crystals are mechanically separated from the product, and the single-crystallinity is confirmed by X-ray Laue diffraction and polarized light optical microscope observation.

Electric transport measurements were carried out in a standard four-point probe method in the (1 0 0) plane in the He exchange gas environment using a PPMS on both cooling-down and warming-up processes.

Magnetic susceptibility measurements were carried out in a Quantum Design SQUID magnetometer in He exchange gas environment in zero-field cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) processes.

The crystal structure was determined using a Bruker single crystal x-ray diffractometer. The structure was refined using the SHELXTL Software Package. Additionally, we have performed Laue diffraction to orientate Mo3Al2C crystals before the sample polishing.

Polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopy

The nature exposed surface of Mo3Al2C is (1 1 0) crystallographic plane. To decompose the Raman signal into separate irreducible representations, we choose to work with the high symmetry (1 0 0) crystallographic plane. The as-grown sample is polished to expose its (1 0 0) crystallographic plane with a lapping film (1 μm, Buehler). A strain-free area for Raman scattering measurement is examined by a Nomarski image. The strain-free area is further examined by comparing the phonon linewidth obtained on the as-grown (1 1 0) crystallographic plane and the polished (1 0 0) crystallographic plane. We did not find any noticeable polishing-induced linewidth broadening.

The polished crystals with (1 0 0) plane used for the Raman scattering study were positioned in a continuous helium flow optical cryostat. The Raman measurements were mainly performed using the Kr+ laser line at 647.1 nm (1.92 eV) in a quasibackscattering geometry along the crystallographic c axis. The excitation laser beam was focused into a 50 × 100 μm2 spot on the ab plane, with the incident power around 12 mW. For the measurement below Tc, an elongated laser spot (50 × 600 μm2) and a weak laser power 1–2 mW is used to reduce laser heating. The scattered light was collected and analyzed by a triple-stage Raman spectrometer and recorded using a liquid nitrogen-cooled charge-coupled detector. Linear and circular polarizations are used in this study to decompose the Raman data into different irreducible representations. The instrumental resolution was maintained better than 1.5 cm−1. All linewidth data presented in this paper have been corrected for the instrumental resolution by fitting the Raman peaks using a Voigt profile. The temperature shown in this paper has been corrected for laser heating (Supplementary Sec. XI).

All spectra shown were corrected for the spectral response of the spectrometer and charge-coupled detector. The obtained Raman intensity Iμv, which is related to the Raman response \({\chi }^{{\prime\prime} }(\omega,T)\): \({I}_{\mu v}(\omega,T)=[1+n(\omega,T)] \, {\chi }_{\mu \nu }^{{\prime\prime} }(\omega,T)\). Here μ(v) denotes the polarization of the incident (scattered) photon, ω is energy, T is temperature, and n(ω, T) is the Bose factor.

The Raman spectra have been recorded from the ab (1 0 0) surface for scattering geometries denoted as \(\mu v=XX,XY,{X}^{{\prime} }{X}^{{\prime} },{X}^{{\prime} }{Y}^{{\prime} },RR,RL\), which is short for Z(μv)Z in Porto’s notation, where X and Y denotes linear polarization parallel to the crystallographic axis [1 0 0] and [0 1 0], respectively; \({X}^{{\prime} }\) and \({Y}^{{\prime} }\) denotes linear polarization parallel to [1 1 0] and [1 \(\bar{1}\) 0], respectively; R = X + iY and L = X − iY denote the right- and left-circular polarizations, respectively; The Z direction corresponds to the c axis perpendicular to the (1 0 0) plane.

Transmission electron microscopy measurement

Single crystal of Mo3Al2C were polished, followed by Ar-ion milling, and studied using a JEOL-2010F field-emission TEM equipped cryogenic sample stage.

Group-theoretical analysis

Group theoretical predictions were performed using the tool provided in the Isotropy Software Suite and the Bilbao Crystallographic Server50,51,52.

The correlation table [Table 1] lists all ten nontrivial subgroups of O and provides the correspondences of irreducible representations. Each subgroup is generated by a subset of the symmetry elements of the parent group, as indicated in the table header. Cubic point groups have a complicated product structure involving a tetragonal (or orthorhombic) and a trigonal subsymmetry. Notably, there are two distinct D2 subgroups within O; one is associated with the tetragonal subsymmetry, while the other combines symmetry elements from both classes. Additionally, the table includes a redundant \({D}_{4}^{*}\) group, which, although identical to the standard-oriented D4, is constructed from different generators; the only difference between the two entries lies in the B1 and B2 labels. Based on Table 1, only the C3 and D3 subgroups show that E irreducible representation does not split while T2 irreducible representation splits into two irreducible representations.

First-principles calculations

First-principles calculations were performed using the VASP code which uses projector-augmented wave formalism53,54,55,56. DFT+U formalism was not used due to the metallic nature of Mo3Al2C with only 4d transition metal cations. Similarly, spin-orbit coupling was ignored. The PBEsol exchange correlation functional57 was used due to the success of this generalized gradient approximation in reproducing the lattice parameters of solids, which is particularly important when studying lattice instabilities. The direct method, which involves displacing atoms one by one and using the Hellmann-Feynman forces to obtain force constants, was employed to calculate the phonon frequencies. A Gaussian smearing of 200 meV for the electronic occupations was employed, along with a 8 × 8 × 8 k-grid to approximate the Brillouin zone integrals. While the unstable phonon frequencies exhibit some sensitivity to these parameters, which is often the case for CDW instabilities58, our calculations with lower values of smearing or denser k-grids did not give qualitatively distinct results.

Data availability

The transport and Raman data generated in this study have been deposited in the figshare database under accession code https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27192603. More data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Anderson, P. W. & Blount, E. I. Symmetry considerations on martensitic transformations: “ferroelectric" metals? Phys. Rev. Lett. 14, 217–219 (1965).

Benedek, N. A. & Birol, T. ‘ferroelectric’ metals reexamined: fundamental mechanisms and design considerations for new materials. J. Mater. Chem. C. 4, 4000–4015 (2016).

Zhou, W. X. & Ariando, A. Review on ferroelectric/polar metals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59, SI0802 (2020).

Ghosez, P. & Junquera, J. Modeling of ferroelectric oxide perovskites: from first to second principles. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 13, 325–364 (2022).

Bhowal, S. & Spaldin, N. A. Polar metals: principles and prospects. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 53, 53–79 (2023).

Hickox-Young, D., Puggioni, D. & Rondinelli, J. M. Polar metals taxonomy for materials classification and discovery. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 010301 (2023).

Li, S. & Birol, T. Free-carrier-induced ferroelectricity in layered perovskites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 087601 (2021).

Shi, Y. et al. A ferroelectric-like structural transition in a metal. Nat. Mater. 12, 1024–1027 (2013).

Puggioni, D. & Rondinelli, J. M. Designing a robustly metallic noncenstrosymmetric ruthenate oxide with large thermopower anisotropy. Nat. Commun. 5, 3432 (2014).

Kim, T. H. et al. Polar metals by geometric design. Nature 533, 68–72 (2016).

Fei, Z. et al. Ferroelectric switching of a two-dimensional metal. Nature 560, 336–339 (2018).

Sakai, H. et al. Critical enhancement of thermopower in a chemically tuned polar semimetal MoTe2. Sci. Adv. 2, e1601378 (2016).

Cheong, S.-W. & Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 6, 13–20 (2007).

van den Brink, J. & Khomskii, D. I. Multiferroicity due to charge ordering. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 434217 (2008).

Fiebig, M., Lottermoser, T., Meier, D. & Trassin, M. The evolution of multiferroics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16046 (2016).

Qi, Y. & Rabe, K. M. Electron-lattice coupling effects in nonadiabatic polarization switching of charge-order-induced ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 106, 125131 (2022).

Liu, Q.-M. et al. Room temperature nonvolatile optical control of polar order in a charge density wave. Nat. Commun. 15, 8937 (2024)

Enderlein, C. et al. Superconductivity mediated by polar modes in ferroelectric metals. Nat. Commun. 11, 4852 (2020).

Salmani-Rezaie, S., Ahadi, K. & Stemmer, S. Polar nanodomains in a ferroelectric superconductor. Nano Lett. 20, 6542–6547 (2020).

Hameed, S. et al. Enhanced superconductivity and ferroelectric quantum criticality in plastically deformed strontium titanate. Nat. Mater. 21, 54–61 (2022).

Jindal, A. et al. Coupled ferroelectricity and superconductivity in bilayer Td-MoTe2. Nature 613, 48–52 (2023).

Smidman, M., Salamon, M. B., Yuan, H. Q. & Agterberg, D. F. Superconductivity and spin-orbit coupling in non-centrosymmetric materials: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 036501 (2017).

Edelstein, V. M. The Ginzburg–Landau equation for superconductors of polar symmetry. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 8, 339 (1996).

Tokura, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal responses from non-centrosymmetric quantum materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 3740 (2018).

Itahashi, Y. M. et al. Nonreciprocal transport in gate-induced polar superconductor SrTiO3. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9120 (2020).

Nagaosa, N. & Yanase, Y. Nonreciprocal transport and optical phenomena in quantum materials. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 15, 63–83 (2024).

Nadeem, M., Fuhrer, M. S. & Wang, X. The superconducting diode effect. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 558–577 (2023).

Yip, S. Noncentrosymmetric superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 15–33 (2014).

Yuan, H. Q. et al. S-wave spin-triplet order in superconductors without inversion symmetry: Li2Pd3B and Li2Pt3B. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 017006 (2006).

Togano, K. et al. Superconductivity in the metal rich Li-Pd-B ternary boride. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 247004 (2004).

Karki, A. B. et al. Structure and physical properties of the noncentrosymmetric superconductor Mo3Al2C. Phys. Rev. B 82, 064512 (2010).

Carnicom, E. M. et al. TaRh2B2 and NbRh2B2: superconductors with a chiral noncentrosymmetric crystal structure. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar7969 (2018).

Zhigadlo, N. D., Logvinovich, D., Stepanov, V. A., Gonnelli, R. S. & Daghero, D. Crystal growth, characterization, and point-contact Andreev-reflection spectroscopy of the noncentrosymmetric superconductor Mo3Al2C. Phys. Rev. B 97, 214518 (2018).

Koyama, T. et al. Normal and superconducting properties of the noncentrosymmetric Mo3Al2C. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 073709 (2013).

Koyama, T. et al. Partial gap opening on the Fermi surface of the noncentrosymmetric superconductor Mo3Al2C. Phys. Rev. B 84, 212501 (2011).

Reith, D., Blaas-Schenner, C. & Podloucky, R. Density functional theory study of phase stability, vibrational, and electronic properties of Mo3Al2C. Phys. Rev. B 86, 104105 (2012).

Huang, F.-T. et al. Polar and phase domain walls with conducting interfacial states in a Weyl semimetal MoTe2. Nat. Commun. 10, 4211 (2019).

Eiter, H.-M. et al. Alternative route to charge density wave formation in multiband systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 64–69 (2013).

Devereaux, T. P. & Hackl, R. Inelastic light scattering from correlated electrons. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 175–233 (2007).

Kuo, C. N., Liu, H. F. & Lue, C. S. NMR characteristics in noncentrosymmetric Mo3Al2C. Phys. Rev. B 85, 052501 (2012).

Mialitsin, A. Raman scattering from layered superconductors: effects of charge ordering, two-band superconductivity, and structural disorder (Ph.D. thesis, Rutgers University-Graduate School-New Brunswick, 2010). https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/30272/

Snow, C. S., Karpus, J. F., Cooper, S. L., Kidd, T. E. & Chiang, T.-C. Quantum melting of the charge-density-wave state in 1T–TiSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 136402 (2003).

Wu, S. et al. Symmetry breaking and ascending in the magnetic kagome metal FeGe. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011043 (2024).

Liu, H. M. et al. Metallic ferroelectricity induced by anisotropic unscreened coulomb interaction in LiOsO3. Phys. Rev. B 91, 064104 (2015).

Sim, H. & Kim, B. G. First-principles study of octahedral tilting and ferroelectric-like transition in metallic LiOsO3. Phys. Rev. B 89, 201107 (2014).

Bauer, E. et al. Unconventional superconducting phase in the weakly correlated noncentrosymmetric Mo3Al2C compound. Phys. Rev. B 82, 064511 (2010).

Bonalde, I. et al. Evidence for conventional superconducting behavior in noncentrosymmetric Mo3Al2C. Phys. Rev. B 84, 134506 (2011).

Gupta, R., Ying, T. P., Qi, Y. P., Hosono, H. & Khasanov, R. Gap symmetry of the noncentrosymmetric superconductor W3Al2C. Phys. Rev. B 103, 174511 (2021).

Kallin, C. & Berlinsky, J. Chiral superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 054502 (2016).

Kroumova, E. et al. Bilbao crystallographic server: Useful databases and tools for phase-transition studies. Phase Transit. 76, 155–170 (2003).

Aroyo, M. I. et al. Crystallography online: Bilbao crystallographic server. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 43, 183–97 (2011).

Hatch, D. M. & Stokes, H. T. Invariants: program for obtaining a list of invariant polynomials of the order-parameter components associated with irreducible representations of a space group. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 951–952 (2003).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Christensen, M. H., Birol, T., Andersen, B. M. & Fernandes, R. M. Theory of the charge density wave in AV3Sb5 kagome metals. Phys. Rev. B 104, 214513 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The spectroscopic work conducted at Rutgers (S.F.W. and G.B.) was supported by the NSF Grant No. DMR-2105001. The sample growth, characterization, and TEM work (X.H.X. F.T.H and S.W.C.) were supported by the DOE under Grant No. DOE: DE-FG02-07ER46382. The theoretical work conducted at the University of Minnesota (E.R. and T.B.) was supported by the NSF CAREER Grant No. DMR-2046020. The work at NICPB was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme grant agreement No. 885413.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.B. and S.W.C. designed and supervised the experiments. S.F.W. and G.B. acquired and analyzed the Raman data. X.H.X. and S.W.C. synthesized the single crystal. F.T.H. and S.W.C. acquired and analyzed the TEM data. E.R. and T.B. did the supercell, domain, and free-energy model analysis and first-principles phonon calculations. All authors contributed to the discussion and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shunsaku Kitagawa, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, S., Huang, FT., Xu, X. et al. Polar charge density wave in a superconductor with crystallographic chirality. Nat Commun 15, 9276 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53627-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53627-1