Abstract

Calcium (Ca) is an essential mineral nutrient and plays a crucial signaling role in all living organisms. Increasing Ca content in staple foods such as rice is vital for improving Ca nutrition of humans. Here we map a quantitative trait locus that controls Ca concentration in rice grains and identify the causal gene as GCSC1 (Grain Ca and Sr Concentrations 1), which encodes a chloroplast vesicle localized homo-oligomeric protein. GCSC1 exhibits Ca2+ transport activity in heterologous assays in yeast and Xenopus laevis oocytes and is involved in the efflux of Ca2+ from the chloroplast to the cytosol. Knockout of GCSC1 results in increased chloroplast Ca concentration, lower stomatal conductance in leaves and enhanced Ca allocation to grains. Natural variation in grain Ca concentration is attributed to the variable expression of GCSC1 resulting from its promoter sequence variation. Our study identifies a chloroplast localized heavy metal-associated domain containing protein that regulates chloroplast Ca2+ efflux and provides a way to biofortify Ca in rice to benefit human nutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcium (Ca) is an essential mineral nutrient for humans, serving as a structural component and a second messenger with critical functions in the skeletal, cardiovascular neurological systems. Inadequate Ca intakes have been linked to many chronic diseases, especially bone health diseases such as rickets in children and osteopenia and osteoporosis in older adults1. Ca deficiency is a global challenge that affects about half of the world’s population2,3. Dairy products are a rich source of Ca but are generally unavailable to most populations suffering from Ca deficiency. Staple food crops, such as rice, are important dietary sources of Ca but the Ca level is generally low and insufficient to satisfy dietary requirement4,5. Biofortification to increase Ca in grains of staple crops is a sustainable approach to alleviate Ca deficiency. However, the genetic basis of Ca accumulation in rice grains is largely unknown, which hampers the development of Ca-biofortified rice varieties.

The accumulation of Ca in rice grains largely depends on root uptake, root-to-shoot translocation, and distribution of Ca to grains. Ca is acquired by the root system from soils and is loaded into xylem in roots for translocation to shoots and distribution to the sink organs such as grains. The intensity of the transpiration stream and the cation exchange capacity of xylem walls are the major factors for long-distance Ca2+ transportation to developing organs6. In addition to being an essential nutrient, Ca2+ also acts as a potent secondary messenger for various aspects of plant physiology including development and stress response7,8. A transient elevation of free Ca2+ concentration in the cytosol can function as an intercellular signal to trigger stimulus-specific response. Distant oscillations of cytosolic Ca2+ level in guard cells, for example, were observed in response to different stimuli and induced Ca2+ programmed stomatal closure8,9. The formation of such stimulus-specific patterns of cellular Ca2+ change relies on the coordinated actions of different Ca2+ channels or transporters that mediate the Ca2+ fluxes across plasma membrane and intracellular membrane8. Various Ca2+ channels and transporters have been identified that mediate the fluxes of Ca2+ between the cytosol and apoplast as well as the intracellular compartments such as vacuole, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria, and chloroplast7,10. For example, the Ca2+ flux into mitochondria and chloroplast is mediated by mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) and chloroplast-localized MCU (cMCU) and bivalent cation transporter BICAT proteins, respectively7,11,12. However, the channel or transporter that mediates the efflux of Ca2+ from chloroplasts into cytosol remains unknown in plants.

In this study, we map a quantitative trait locus (QTL) qGCa-3 that controls Ca concentration in rice grains and identify the causal gene as GCSC1. GCSC1 encodes a heavy metal-associated domain-containing protein localized in chloroplast vesicles that might functions either as a Ca2+-permeable channel or a Ca2+ flux modulator to mediate the efflux of Ca2+ from chloroplasts to cytosol. We show that GCSC1 could form a homo-oligomer and plays a role in maintenance of chloroplast Ca2+ homeostasis and in allocation of Ca2+ to grains via stomatal conductance control. We further reveal that the natural variation of Ca concentration in rice grains is attributed to the variable expression of GCSC1 resulting from its promoter sequence variation. Our studies uncover a promising gene for breeding Ca-biofortified rice varieties and provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying Ca2+ fluxes between the cytosol and the chloroplast.

Results

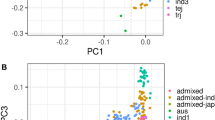

Map-based cloning of qGCa3

By using the rice recombinant inbred lines derived from a cross between Lemont (LM) and TeQing (TQ) (LT-RILs), and TeQing-into-Lemont backcross introgression lines (TILs), we previously identified 134 QTLs that control the variation of 16 elemental concentrations in rice grains13, including 4 QTLs controlling the variation of grain Ca concentration. One of the grain Ca QTLs was repeatedly detected on chromosome 3 (designated as qGCa3) in both mapping populations (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 1a), whereas other three QTLs on chromosome 4, 10 and 12 were detected in only one population13. Strontium (Sr) is a chemical analog of Ca, and Sr accumulation in rice grain is positively correlated to that of Ca13,14. A Sr QTL was also detected in the same region as qGCa3 (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 1b), suggesting that qGCa3 may also control the variation of Sr concentrations in rice grains. We resequenced the whole genomes of LT-RIL population and performed QTL analysis by using the bins as markers14, and narrowed down the qGCa3 locus to an average of 1.94 cM based on either grain Ca (Fig. 1c) or Sr concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 1c). By fine mapping, the qGCa-3 was narrowed down to a ~ 120 kb region between the markers L15406 and L15525 (Fig. 1d). Among the 16 genes in this mapping region (Supplementary Data 1), LOC_Os03g27040 was identified as the candidate gene, which encodes a heavy metal-associated (HMA) domain-containing protein (Fig S2a, b). Transmembrane prediction by DeepTMHMM, MemBrain, or TmAlphaFold suggested no obvious transmembrane domain, whereas two potential transmembrane domains were predicted by DAS (Fig S3a, b; see “Methods”). The protein sequence is conserved in the C-terminal HMA domain but highly variable in the other regions (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Sequence analysis of LOC_Os03g27040 revealed a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) between LM and TQ and a SNP between the reference sequence (Nipponbare) and the two parents, leading to amino acid sequence changes of histidine-to-arginine at position 51 (H51R) and tyrosine-to-serine at position 72 (Y72S), respectively (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. 2a). The variable H51R between LM and TQ is not in the HMA domain nor the N-terminal signal peptide region, suggesting that it might not alter the protein function (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Comparison of the promoter sequence of LOC_Os03g27040 identified 13 SNPs and 6 indels between LM and TQ, including deletions of 58-bp (Del15), 16-bp (Del16) and 6-bp (Del6) in TQ (Fig. 1e). Another potential candidate gene LOC_Os03g27080 which was annotated as Calmodulin-binding transcription activator 2 (Supplementary Data 1) exhibits two variable amino acids, but none of them is located in the conserved domain (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Furthermore, the expression levels of LOC_Os03g27080 in roots and shoots were similar between TQ and LM (Supplementary Fig. 4b), suggesting that LOC_Os03g27080 was likely not the candidate gene for qGCa3.

a–c The LOD profiling of qGCa3 on chromosome 3 in the LT-RIL population grown in multiple years under different conditions. QTL analyses were performed based on grain Ca (a, c) or Sr (b) concentration by using RFLP markers (a, b) or SNPs (c) derived from whole genome resequencing. F flooded; U unflooded. d Fine mapping of qGCa3. The grain Sr of BC2F2;4 plants of six recombinants and the corresponding control lines were determined. e Gene structure and sequence variation of GCSC1 among Nipponbare (NIP), two parental lines “Lemont“(LM) and “TeQing” (TQ). Blue bars, exons; orange bars, untranslated regions; black bar, insertion; vertical lines, SNPs; In insertion; Del deletion. The concentrations of Ca (f) and Sr (g) in grains of two NILs. NIL(TQ), NIL with genotype as TQ; NIL(LM), NIL with genotype as LM. Data in (d, f–h) are presented as mean ± SD with indicated biological replicates. h Expression level of GCSC1 in the root, basal node, and shoot of NIL(TQ) and NIL(LM). Data was presented as mean ± SD with three biological replicates with three plants in each replicate. * and ** in (d, f, g) indicates significant difference at p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively (two-sided Student’s t-test). ns, no significant difference. DW, dry weight. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. P values detailed in Source data.

We developed near isogenic lines (NIL) in the TQ background which contain the genomic fragment from either TQ or LM at the qGCa3 locus. The NIL progeny containing the TQ allele (denoted as NIL(TQ)) accumulated significantly higher concentrations of both Ca and Sr in grains compared to NIL(LM) without obvious changes of major agronomic traits (Fig. 1f, g; Supplementary Fig. 5a–f), suggesting that the TQ allele contributes to higher Ca and Sr in the grain. LOC_Os03g27040 was mainly expressed in the shoots at the vegetative stage, and its expression level was significantly higher in NIL(LM) than in NIL(TQ) (Fig. 1h), suggesting that higher Ca and Sr concentrations in the grain of NIL(TQ) might be due to a lower expression level of LOC_Os03g27040. We therefore designated LOC_Os03g27040 as GCSC1 for GrainCa andSrConcentrations 1 in rice.

GCSC1 is the causal gene for qGCa3

To investigate the function of GCSC1, we generated three independent knockout mutants of GCSC1 in rice variety Zhonghua 11 background by using the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 6). Elemental analysis showed that gcsc1 contained 10–30% and 21–43% higher Ca and Sr concentration, respectively, in the grain than the wild-type (WT) without penalties on major agronomic traits (Fig. 2b–d; Supplementary Fig. 7a–f). The higher Ca concentration in the grains of gcsc1 was further confirmed by microfocus X-ray fluorescence (µ-XRF) scanning (Fig. 2e–f). Other elements were not significantly affected, except Fe and Zn which were slightly but significantly increased and decreased, respectively, in the grain of gcsc1 (Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 9). Transgenic complementation of the full genomic sequence of GCSC1 from LM into the gcsc1 mutant decreased grain Ca and Sr concentrations to the levels of WT (Fig. 2g-h), confirming the effect of GCSC1 on Ca and Sr accumulation in the grain.

a Knockout mutants of GCSC1 generated by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology. Two gRNA targets are indicated with vertical lines. PAM sits are underlined. Deletions are indicated with red lines. gcsc1-1 is frame shift mutation; gcsc1-2 and gcsc1-3 are premature termination mutants. b The growth phenotype of WT and gcsc1-1 grown in a paddy field at harvesting stage. Bar, 25 cm. The concentrations of Ca (c) and Sr (d) in the grains of WT and gcsc1. e X-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanning the grains of WT and gcsc1. The red and blue colors represent high and low Ca concentration, respectively. Bar, 5 mm. f Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of XRF images in (e). g, h Transgenic complementation of gcsc1 by transforming the cDNA of GCSC1 from LM and expressed under the control of its native promoter. Grain Ca (g) and Sr (h) concentration of WT, gcsc1, and two independent complemented lines were determined. i Genetic complementation of gcsc1 by crossing with NIL(TQ) or NIL(LM). The Ca (i) and Sr (j) concentrations in the grains of WT, gcsc1, NIL(TQ), NIL(LM), and F1 plants were determined. Data in (c, d, f–h) are presented as mean ± SD with indidated biological replicates. Data in (i–j) are shown as boxplots displaying the maximum and minimum, first and third quantiles, and the median. The number below each box indicates the number of biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two-sided Student’s t-test (c, d, f) or Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test (g–j). *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; Different letters above the bars in (g–j) indicate significant difference at p ≤ 0.05. DW, dry weight. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. P values detailed in Source data.

To further confirm that GCSC1 is the causal gene for qGCa3, we performed a genetic complementation by crossing the WT and gcsc1 with NIL(LM) and NIL(TQ), respectively. The grain Ca and Sr concentrations of gcsc1 and NIL(TQ) were significantly higher than those of WT and NIL(LM) (Fig. 2i, j). Grain Ca and Sr concentrations of two independent lines of gcsc1 × NIL(LM) F1 were significantly lower than that of gcsc1, similar to the level in WT × NIL(LM) F1; whereas grain Ca and Sr concentrations of gcsc1 × NIL(TQ) F1 plants were similar to that of gcsc1 (Fig. 2i, j). Furthermore, lower Ca and Sr concentrations were observed in grains of gcsc1 × NIL(LM) F1 plants than that of gcsc1 × NIL(TQ) F1 plants (Fig. 2i, j). These results indicate that the LM GCSC1 allele, but not the TQ allele, complements the knockout gcsc1 allele and suggests that GCSC1 is the causal gene for qGCa-3. The concentrations of Na and Cu were higher in the grain of NIL(LM) compared to that of NIL(TQ) (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Tissue expression pattern of GCSC1

GCSC1 was expressed in most of the plant tissues throughout the growth period of both LM and TQ grown in a paddy field, with leaves showing much higher expression than other tissues (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. 11a). The leaf-specific expression of GCSC1 was further confirmed in stable transgenic plants transformed with a GCSC1-eGFP fusion construct driven by the GCSC1 native promoter from LM. The GFP fluorescence was only detected in the leaf blade with strong GFP signals being observed in the chloroplasts of the mesophyll cells (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, expression of GCSC1 in leaf blades displayed a diurnal rhythmic pattern peaking after the dark-to-light transition (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 11b), similar to that of the circadian regulator gene OsCCA1 but opposite to that of OsPRR117 (Supplementary Fig. 12a-d). Expression of GCSC1 was not affected by Ca deficiency or excess levels of Ca or Sr (Supplementary Fig. 13a-f).

a Expression level of GCSC1 in different organs at different growth stages. Samples were taken from LM grown in a paddy field. b Tissue-specific expression of GCSC1 in leaf blade. Cross section of the leaf blade of transgenic lines expressing GCSC1pro::GCSC1-GFP. Bar, 40 µm. c Diurnal rhythmic expression of GCSC1 in the leaf blade. The leaf blades of three-week-old LM seedlings grown hydroponically were sampled every 2 h for 2 d. The white and grey background represent light and dark conditions, respectively (0 = dawn). The relative expression level of GCSC1 in (a, c) was normalized to the rice OsACTIN1 gene and presented as mean ± SD with three biological replicates with three plants in each replicate. d Subcellular localization of GCSC1 in stable transgenic rice plants expressing UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP. The rectangle indicates the enlarged region. Bar, 10 µm. e Chloroplast localization of GCSC1 determined by western blot. Total protein were extracted from the leaf blade of UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic plants and then fractionated into chloroplast and ER proteins and subjected to immunoblotting with antisera against GFP, RbcL (chloroplast marker), Bip2 (ER marker), and UGPase (cytosol marker). f Immunogold electron microscopy analysis revealed the localization of GCSC1 to the chloroplast vesicle. Ultrathin sections were prepared from the leaf of the UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic line followed by immunogold labeling using GFP antibodies. The yellow rectangles indicate the enlarged parts shown on the right panel. Yellow arrows denote the chloroplast vesicles; blue arrows indicate the gold particles on the chloroplast vesicle that is undergoing of invagination from or fusion into the inner envelope membrane. E envelope membrane; V vesicle; TM thylakoid membranes; S starch; C cytosol. Bar, 1 µm. g Chloroplast membrane localization of GCSC1 determined by LC-MS/MS. Chloroplast proteins from WT plants were extracted and fractionated into stroma and membrane fractions. Proteins in each fraction were determined by LC-MS/MS. The abundance of GCSC1, stroma, and membrane marker proteins were shown in log value transformed. IBAQ, intensity-based absolute-protein-quantification. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

GCSC1 is localized to the chloroplast vesicles

The subcellular localization of GCSC1 was investigated in the protoplasts prepared from rice transgenic line expressing a maize Ubiquitin (UBI) promoter driven GCSC1-GFP fusion construct (UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP). Compared to the ubiquitous GFP signal in the protoplasts of UBIpro::GFP line, the GFP fluorescence in the UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP line was distributed non-uniformly around the chlorophyll autofluorescence (Fig. 3d). Some dot-like signals close to the envelope membrane were also observed on chloroplasts (Fig. 3d), suggesting the chloroplast localization of GCSC1. We further purified the chloroplast and ER proteins from the UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic line and performed immunoblotting using the antisera against GFP and several organelle marker proteins, including RbcL (chloroplast), Bip2 (ER), and UGPase (cytosol). Western blot analysis using the GFP antibody showed a single band with the predicted size in the fractions of total proteins and chloroplast proteins, but not in ER proteins (Fig. 3e), confirming the localization of GCSC1 to the chloroplast.

To determine high-resolution sub-organelle localization of GCSC1, immunogold electron microscopy analysis was performed in the leaf of UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic line using the antibody against GFP. Most of gold particles were found on the vesicle-like structures close to the inner envelope membrane, which are likely the chloroplast vesicles (Fig. 3f; Supplementary Fig. 14a, b). Chloroplast vesicles are formed by invagination of the inner envelope membrane and can be fusion into the inner envelope membrane16,18. Indeed, gold particles were found on the vesicle that was undergoing of invagination from or fusion into the inner envelope membrane (Fig. 3f). In chloroplast, some gold particles were also found outside of vesicles which may be due to the non-specific labeling. By contrast, gold particles were not found on the chloroplast vesicle of the control transgenic line expressing GFP alone (UBIpro::GFP) (Supplementary Fig. 14a, b).

To confirm the localization of GCSC1 to chloroplast vesicle rather than in the stroma, we purified chloroplasts from WT plants and fractionated the proteins into the membrane and stroma fractions. Quantification of proteins by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) revealed that GCSC1 was present only in the membrane fractions, co-existing with several chloroplast membrane proteins (Fig. 3g), including the Translocon on the Outer and Inner Chloroplast membrane TOC75 and TIC6219, and thylakoid membrane localized light-harvesting chlorophyll-binding protein LHCP II20. In contrast, GCSC1 was not detected in the stroma protein fraction (Fig. 3g). We further extracted chloroplast membrane proteins by using two alkaline extraction methods (pH at 8 or 11.5) to strip away the potential membrane-associated peripheral proteins and confirmed the presence of GCSC1 in the membrane protein fraction but not in stroma protein fraction by Western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 15). Taken together, the results indicate that GCSC1 was localized to the chloroplast vesicles.

GCSC1 exhibits Ca2+ transport activity

On the basis of its subcellular localization, we hypothesize that GCSC1 may exhibit Ca2+ transport activity and transport Ca2+ across the chloroplast vesicles. To test this hypothesis, we first determined the binding activity of GCSC1 to Ca2+ in vitro using microscale thermophoresis (MST) assay. Compared to the GFP alone purified from the UBIpro::GFP line showing no binding activity to Ca2+, the GCSC1-GFP recombinant protein purified from the UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic rice plants was able to bind Ca2+ with a high affinity (Kd of 0.14 ± 0.079 µM; Fig. 4a).

a Determination of the binding activity of GCSC1 to Ca2+ using microscale thermophoresis. The GCSC1-GFP or GFP protein was purified from UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP or UBIpro::GFP transgenic plants, respectively, and then mixed with various concentrations of CaCl2 (ligand). b Ca2+ transport activity of GCSC1 in yeast. The yeast mutant k667 transformed with empty vector (EV) or GCSC1 from TQ or LM were serially diluted and spotted on the media containing glucose (Glu) or galactose (Gal) as carbon source and supplied with various concentrations of CaCl2. c, d Growth curves of various yeast strains in the liquid Glu (c) or Gal (d) media supplied without or with 5 mM CaCl2. The O.D.600 was measured at indicated times. The growth curves of yeast strains transformed with GCSC1 from TQ and LM were almost identical and were overlapped in (d). e Ca concentrations in yeast cells transformed with EV or GCSC1 from TQ or LM. Data in (a, c–e) are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). * indicates significant differences between EV and GCSC1 at p ≤ 0.05 (two-sided Student’s t-test). f Ca2+ transport activity of GCSC1 in everted membrane vesicles of E. coli BL21 strain transformed with EV or GCSC1 from TQ or LM. The Ca concentrations in everted membrane vesicles were determined at 0 and 15 min after incubation, and the Ca2+ efflux relative to time point 0 was calculated. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5). Different letters indicate significant differences p ≤ 0.01 (Fisher’s LSD test). g Plasma membrane localization of GCSC1-GFP in Xenopus oocytes. h, Two-electrode voltage-clamp characterization of GCSC1 in Xenopus oocytes. AtCNGC14 expressed oocytes were used as positive control and water-injected oocytes showing background currents were used as negative control. The currents were recorded in a bath solution containing 20 mM CaCl2 by a stepwise mode. i, Steady-state current-voltage (I-V) relationships of recordings as in (h). Data are presented as mean ± SE with four biological replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. P values detailed in Source data.

Next, we tested the Ca2+ transport activity of GCSC1 in yeast. Expressing GCSC1-GFP fusion construct from a high copy number 2 µ origin pYES2 plasmid revealed that GCSC1-GFP likely localizes in the endomembrane system (Supplementary Fig. 16). The yeast cells transformed with GCSC1 from LM or TQ were more sensitive to excess Ca and grew more slowly than the cells harboring an empty vector (Fig. 4b–d). Furthermore, the Ca content in the yeast cells expressing GCSC1 was significantly increased compared to the empty vector control (Fig. 4e). There were no significant differences in the growth rate or the Ca content between the yeast cells carrying GCSC1 from LM and TQ (Fig. 4b-e), suggesting the variable amino acid of GCSC1 (H51R) from LM and TQ did not alter its Ca2+ transport activity. The Ca2+ transport activity of GCSC1 was further determined in everted membrane vesicles prepared from E. coli cells. The membrane of E. coli cells was purified and everted into membrane vesicles in a solution containing 50 mM Ca2+ and then transferred to the same solution without Ca. After 15 min incubation, 85.2% and 64.3% of Ca was effluxed from the inverted membrane vesicles harboring GCSC1 from LM or TQ, respectively; whereas, no obvious Ca efflux was observed for the control inverted membrane vesicles harboring an empty vector (Fig. 4f). There was no significant difference in Ca efflux between GCSC1 from TQ and LM (Fig. 4f).

We further examined the Ca2+ transport activity of GCSC1 in Xenopus oocytes using two-electrode voltage clamp recording. GCSC1-GFP fusion construct was expressed and localized to the plasma membrane of oocytes (Fig. 4g). To avoid the potential effect of GFP on the transport activity, GCSC1 was expressed in oocytes without the GFP fusion. In the presence of 20 mM CaCl2, the oocytes injected with GCSC1 cRNA displayed a large inward current at −150 mV; the amplitude of the current was larger than that injected with the cRNA of AtCNGC14, a known Ca2+-permeable channel gene from Arabidopsis thaliana21 (Fig. 4h). In contrast, the water-injected control oocytes showed a negligible current (Fig. 4h). A current-voltage (I-V) relationship plot revealed that oocytes expressing GCSC1 displayed significant inward currents slightly higher than that of AtCNGC14 (Fig. 4i). Taken together, the results from heterologous assays in yeast, E. coli and Xenopus oocytes provide strong evidence that GCSC1 exhibits Ca2+ transport activity in heterologous assays.

GCSC1 mediates Ca2+ efflux from the chloroplast

Next, we tested whether GCSC1 mediated the flux of Ca2+ across the chloroplast using a Non-invasive Micro-test Technique (NMT). Intact chloroplasts were purified from leaves of WT and gcsc1 and subjected to real-time measurement of Ca2+ flux. The net Ca2+ efflux of gcsc1 chloroplasts was significantly reduced by 30.8−38.4% compared to the WT (Fig. 5a-b). Quantification of the Ca content in the intact chloroplasts showed that gcsc1 accumulated a significantly higher level of Ca in the chloroplasts than the WT (Fig. 5c), which was consistent with the reduction of Ca2+ efflux from chloroplasts in gcsc1 (Fig. 5a-b).

a Measurement of Ca2+ flux in chloroplasts by Non-invasive Micro-test Technique (NMT). Chloroplasts were purified from the leaves of WT and two independent knockout gcsc1 mutants and used for time-course recording of net Ca2+ flux for 5 min with a 5 s interval. Each data point is presented means ± SD with three independent measurements. b The integrated net Ca2+ flux over 5 min for the chloroplasts of WT and gcsc1. c The Ca content in the intact chloroplasts isolated from leaves of WT and gcsc1. The amount of Ca was normalized to the chloroplast number. d N-fusion of targeting peptides directs YC3.6 to chloroplast, nuclear or cytosolic. FRET-based Ca2+ imaging in the chloroplasts (e), nucleus (f), or cytosol (g) of WT and gcsc1 plants transformed with chloroplast targeting Ca2+ indicator cpYC3.6, nuclear Ca2+ indicator nYC3.6 or cytosolic Ca2+ indicator ctYC3.6. Representative confocal images of the cross-section of leaf blades of WT and gcsc1 were showed. Bar, 20 µm. Quantitative analysis of the fluorescent intensity ratio of cpVenus to ECFP for cpYC3.6 (h), nYC3.6 (i), or ctYC3.6 (j) as shown in (e–g). Data in (b–c) are presented as means ± SD with indicated biological replicates on the bottom of each column. Data in (h–j) are presented as boxplots displaying the maximum and minimum, first and third quantiles, and the median. The number below each box indicates the number of replicates. * in (c) and ** in (b) indicate significant differences between WT and gcsc1 at p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively (two-sided Student’s t-test). P values in (h–j) were generated by two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To visualize Ca in the chloroplasts, we generated stable transgenic plants by expressing a fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based Ca2+ indicator Yellow Cameleon 3.6 (YC3.6)22 in the WT and gcsc1 background (Fig. 5d). The YC3.6 was targeted to chloroplast (cpYC3.6) by fusion with a chloroplast stroma-targeted peptide23,24. The YC3.6 was also targeted to the nucleus (nYC3.6) or cytosol (ctYC3.6) by fusion with a nuclear localization signal (NLS)25 or a nuclear export signal (NES)26, respectively, to monitor the nuclear and cytosolic Ca2+ levels. We imaged the YC3.6 signal in the cross-section of leaf blade and calculated the fluorescent intensity ratio of circularly permuted Venus (cpVenus, an improved YFP version present in the YC3.6) to the enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP), which is positively correlated with the Ca2+ level22. The cpVenus/ECFP intensity ratio of cpYC3.6 in the chloroplasts was significantly (P < 0.001) higher in gcsc1 than that of WT, indicating a higher Ca2+ level in the chloroplasts of gcsc1 (Fig. 5e, h). The cpVenus/ECFP intensity ratio of ctYC3.6 in the cytosol was decreased significantly (P < 0.05) in gcsc1, whereas no difference was observed for the cpVenus/ECFP ratio of nYC3.6 in the nucleus between gcsc1 and WT (Fig. 5f, g, i, j). These results indicate that knockout of GCSC1 resulted in increased accumulation of Ca2+ in the chloroplasts and decreased cytosolic Ca2+ levels.

Self-interaction and oligomeric state of GCSC1

Given the relatively small size of the GCSC1 protein (184 amino acids; 18.4 kDa), it is unlikely that its monomer functions as a Ca2+ channel or transporter. We hypothesized that GCSC1 may form an oligomer, as oligomerization is a common feature for plant ion channels, including several Ca2+-permeable channels27,28. To test this hypothesis, we first used a split-ubiquitin based yeast two-hybrid assay to assess self-interaction of GCSC1. The interaction between GCSC1 proteins was observed as reflected by the growth of yeast cells co-expressing GCSC1-Cub and NubG-GCSC1 on the selection medium, similar to the positive control by co-expression with GCSC1-Cub and NubI (the wild type N-terminal ubiquitin having high affinity to Cub) (Fig. 6a). We further verified the self-interaction of GCSC1 in plant cells using the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay. When GCSC1-nYFP and GCSC1-cYPF were co-expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermis cells, YFP-based fluorescence was observed on the chloroplast (Fig. 6b). These results demonstrate a physical interaction among GCSC1 proteins on the chloroplast, consistent with its subcellular localization (Fig. 3d).

a Self-interaction of GCSC1 determined by split-ubiquitin based yeast two-hybrid analysis. The 1:10 serial dilutions of yeast cells transformed with indicated plasmids were spotted on control medium (left) or selective medium (right). APP and Fe65 proteins were used as positive control. b Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay (BiFC) showing self-interaction of GCSC1 on chloroplast. The N-terminal (nYFP) or C-terminal split YFP (cYFP) were in-frame fused with GCSC1, respectively, and were co-expressed in N. benthamiana leaf epidermis cells. Representative confocal images were shown. Bar, 10 µm. c Determining the oligomerization of GCSC1 by BN-PAGE. Total proteins extracted from WT or UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic line were resolved by BN-PAGE (upper panel) under nondenaturing condition and then immunoblotted with anti-GFP antibody. The loading control was defined by staining the Rubisco using Ponceau S stain. Approximate molecular weights (kDa) are shown on the left. The arrows on the right denote the putative oligomers of GCSC1-GFP fusion protein with indicated molecular weights. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To determine the oligomeric state of GCSG1, we extracted the native GCSG1 protein complex from the UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP line and separated the protein complex using blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE), which allows the separation of membrane protein complexes under nondenaturing conditions29. The proteins purified from the leaves of WT or UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic line were resolved by SDS-PAGE under denatured condition followed by immunoblotting with GFP antibody. A single band corresponding to the GCSC1-GFP fusion protein was detected for the UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic line but not for WT, demonstrating the specificity of the GFP antibody (Fig. 6c). In parallel, the proteins were resolved by BN-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with the GFP antibody. Besides the band corresponding to the monomer of GCSC1-GFP fusion protein (49.6 kDa in size), bands with approximate size equivalent to the dimer and tetramer of GCSC1-GFP fusion protein were also detected (Fig. 6c). No band was detected for the proteins purified from WT (Fig. 6c). These results indicate that GCSC1 could form homodimers and homotetramers.

Knockout of GCSC1 alters Ca allocation and stomatal conductance

To investigate whether knockout of GCSC1 affects the accumulation of Ca and Sr, we determined the Ca and Sr concentrations in the roots, different leaves, and the xylem sap of WT and gcsc1 grown hydroponically with various concentrations of Ca and 0.5 μM Sr, and found no significant difference (Supplementary Fig. 17a–f; Supplementary Fig. 18a, b), suggesting that GCSC1 does not affect the uptake of Ca and Sr by roots or root-to-shoot translocation at the seedling stage. To examine whether GCSC1 affects the Ca allocation between the mature and newly developed tissues under Ca limited condition, we grew plants in Ca sufficient condition (180 μM) and then transferred them to a low Ca nutrient solution (1.8 μM) until a new leaf fully emerged (Fig. 7a). The fresh weight of newly developed leaves of gcsc1 was significantly lower under sufficient Ca condition but was 25.1-43.6% higher than that of the WT under Ca limited condition (Fig. 7b), suggesting that the development of newly leaves were less inhibited in gcsc1 than WT under the Ca limited condition. The Ca concentrations in the mature and new leaves of gcsc1 were significantly lower than those of WT under the Ca limited condition (Fig. 7c) but there was no significant difference in the total amount of Ca in either mature or new leaves between WT and gcsc1 (Supplementary Fig. 19a), suggesting that knockout of GCSC1 did not change the total Ca amount in both mature and new leaves grown under Ca limited condition.

a Diagram showing the treatment of WT and gcsc1 under Ca sufficient (180 μM) or limited (1.8 μM) conditions. Five-leaf-old plants grown hydroponically in nutrient solution containing 180 μM Ca were kept growing or treated with 1.8 μM Ca until a new leaf fully emerged. b Fresh weight of new leaves of WT and gcsc1 plants grown hydroponically as described in (a). c Ca concentrations in the mature and new leaves of WT and gcsc1 plants grown under Ca sufficient or limited conditions. d–f The stomatal conductance (d), transpiration rate (e), and intercellular CO2 concentration (f) on flag leaves of WT and gcsc1 at grain filling stage. g, h, The relative water loss in the flag leaves of WT and gcsc1 at grain filling stage (g) or in the second fully expanded leaves of four-week-old plants grown hydroponically (h). i, Environmental scanning electron microscopy images of three levels of stomatal opening. Bar, 10 µm. j The percentage of three levels of stomatal opening in WT and gcsc1. k Examination of H2O2 accumulation in the guard cells of WT and gcsc1 by staining with a fluorescence dye H2DCFDA. Bar, 10 mm. l Quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity of H2DCFDA in the guard cells of WT and gcsc1. Data are presented as means ± SD in (b–j) with n = 9 in (b), 3 in (c, g, h), 6 in (d–f), 42-49 in (j) and 33-44 in (l). * and ** indicate significant differences between WT and gcsc1 at p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively (two-sided Student’s t-test). DW, dry weight. FW, fresh weight. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. P values detailed in source data.

Transpiration is a major factor driving the accumulation of Ca to transpiring tissues30. The transpiration rate of plant leaves is largely controlled by the stomatal conductance. We determined the stomatal conductance and transpiration rate of the flag leaves of field-grown plants during grain filling and found significantly lower stomatal conductance and transpiration rate, as well as lower intercellular CO2 concentration, in the gcsc1 mutants than the WT (Fig. 7d, f). Consistent with the lower stomatal conductance and transpiration rate, the water loss of detached flag leaves of gcsc1 was significantly lower than that of the WT at the grain filling stage (Fig. 7g). Similarly, lower water loss was also found in the detached leaves of gcsc1 at the seedling stage (Fig. 7h). We further examined the stomatal status in leaves and found that 53–60% of the stomata were completely closed in the leaves of gcsc1 mutants, compared with 32% in the WT (Fig. 7i, j). Taken together, knockout of GCSC1 resulted in smaller stomatal conductance and lower transpiration rate in flag leaves due to the increased stomata closure, which could reduce Ca flow to flag leaves and thus allow more Ca flow to the panicle and the grain. Consistently, the Ca concentration in flag leaves of gcsc1 mutants was generally lower than that of the WT at the grain filling stage (Supplementary Fig. 19b).

To further investigate the functions of GCSC1, we performed transcriptomic analysis on the flag leaves of WT and gcsc1 during grain filling. There were 409 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between WT and gcsc1, including 142 up-regulated genes and 267 down-regulated in genes in gcsc1 (Supplementary Fig. 20a; Supplementary Data 2). Gene Ontology enrichment analysis showed that these DEGs were enriched in signal transduction, stress response, and flavone biosynthetic process (Supplementary Fig. 20b). In particular, several genes involved in the generation and scavenge of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were down-regulated in gcsc1, including six peroxidase genes and one catalase gene that were participated in the removal of H2O2 or superoxide31,32, and two NADPH oxidases (also known as respiratory burst oxidase homologs), OsRbohF and OsRbohG, which are responsible for ROS production33,34 (Supplementary Data 2; Supplementary Fig. 21). The changes in the expression of genes involved in ROS production and scavenging may alter the balance of ROS in the flag leaf and promote the stomatal closure in gcsc1. To confirm this speculation, we determined the ROS level in the guard cells by staining with a fluorescence dye, 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA). We found that gcsc1 mutant plants accumulated more ROS in the guard cells than those of WT (Fig. 7k, l), which could explain the increased stomatal closure in gcsc1.

Analysis of natural variation of GCSC1

To gain insight into the contribution of genetic variation at GCSC1 to variation of grain Ca/Sr content in rice, we analyzed the sequence of GCSC1 in the resequenced genomes of 4726 diverse worldwide rice accessions35 and identified three non-synonymous polymorphisms in the coding sequence of GCSC1, including the polymorphic H51R between TQ and LM and the Y72S between Nipponbare and TQ/LM (Fig. 1e; Fig. 8a; Supplementary Data 3). A total of four haplotypes of GCSC1 were identified according to the three non-synonymous polymorphisms with the haplotype I being the largest haplotype group (Fig. 8b; Supplementary Data 3). Taking the advantage of the rice grain ionomic data we had previously reported36, we found no significant differences of grain Ca or Sr concentrations among accessions with different GCSC1 haplotypes (Fig. 8c, d; Supplementary Fig. 22), suggesting that the variations in the GCSC1 coding sequence did not affect the natural variation of Ca/Sr accumulation in rice grain. Consistently, the four GCSC1 haplotypes showed similar Ca2+ transport activities in yeast (Supplementary Fig. 23).

a The polymorphic sites in the promoter or coding region of GCSC1 among natural rice accessions. Del15, 58-bp deletion; In29, 28-bp insertion; Del16, 16-bp deletion; S42(In), Ser insertion at position 42. b Haplotype analysis on the coding sequence of GCSC1 in 2956 rice accessions. Grain Ca (c, e, g) and Sr (d, f, h) concentrations in rice accessions with different haplotypes in the coding region (c, d), with or without the indicated indel in the promoter region (e, f), or with different promoter haplotypes derived from the combination of three indels in the promoter (g, h). Data in (c–h) are shown as boxplots displaying the maximum and minimum, first and third quantiles, and the median. The numbers under the boxes are the accession number; different letters above the boxes indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 (Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test without adjustment). The correlations of the relative expression of GCSC1 in leaves with the grain Ca (i) or Sr (j) concentrations in 40 rice accessions. The expression of GCSC1 in the leaves of 4-week-old plants was determined by qRT-PCR. DW, dry weight. k The proposed model of GCSC1 in regulation of Ca allocation in rice. The chloroplast vesicle-localized CGSC1 mediates Ca2+ efflux from chloroplasts to cytosol probably by vesicle traffic from thylakoid membrane to the inner envelope membrane (left panel). Knockout of GCSC1 results in elevation of Ca level in chloroplasts which triggers the production of ROS in guard cells and promotes stomatal closure and reduces transpiration rate, and thus promotes more Ca allocation to grains and results in higher Ca level in grains (right panel). The red dots represent Ca2+. Various Ca2+ channels or transporters involved in the Ca2+ fluxes are indicated. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. P values detailed in source data.

We further determined the contribution of the two major variances in the promoter of GCSC1 on the variation of grain Ca/Sr, including the Del15 and Del16 identified between TQ and LM (Fig.1e; Fig. 8a). In the genomic region of Del15, another sequence variance was isolated in which a 28-bp insertion (In29) was detected (Fig. 8a). The rice accessions with Del15 or In29 had a significantly higher level of grain Ca and Sr than the accessions without these two indels (Fig. 8e, f). In contrast, no difference was observed between the accessions with or without Del16 (Fig. 8e, f), suggesting the Del15 and In29 in the promoter of GCSC1 contributed to the variation of grain Ca/Sr concentrations. Comparisons of rice accessions with different combinations of the three indels revealed the highest grain Ca/Sr concentrations in the accessions containing the In29 (Fig. 8g, h), indicating the In29 in the promoter of GCSC1 is an elite allele that could be used for breeding high grain Ca varieties.

To examine whether the variation of grain Ca/Sr correlated with the GCSC1 expression level, we randomly selected 40 rice accessions with different combinations of indels in the promoter of GCSC1. Correlation analysis revealed significant negative correlations between grain Ca and Sr concentrations and the expression level of GCSC1 in leaves (Pearson’s R2 = 0.13 and 0.19, P = 0.022 and 0.0054, respectively; Fig. 8i, j). These results indicate that the natural variation of Ca/Sr concentration in rice grains is attributed to the variable expression of GCSC1.

Discussion

In this study, we mapped a QTL, qGCa-3, that controls the variation of grain Ca/Sr concentration in rice (Fig. 1a–c; Supplementary Fig. 1a–c), and identified GCSC1 as the causal gene for qGCa-3 by genetic and transgenic complementation (Fig. 2g–j). Knockout of GCSC1 enhanced Ca concentration in the grains by 10–30% without yield penalty or obvious changes in agronomic traits (Fig. 2b–f; Supplementary Fig. 7a–f), and thus has the potential for Ca biofortification in rice. The concentrations of Fe and Na were also elevated but Zn was decreased in grains of gcsc1 suggesting GCSC1 could be also used for Fe biofortification but not for Zn. We showed that the sequence polymorphisms in the GCSC1 promoter region, not in the coding region, cause the natural variation of Ca concentration in rice grains (Fig. 8c–h). We also identified an elite GCSC1 haplotype containing a 28-bp sequence insertion in its promoter that enhances grain Ca concentration significantly (Fig. 8a–h). This elite haplotype can be used in breeding rice varieties with enriched grain Ca through traditional marker-assisted selection approach.

GCSC1 encodes a previously unknown functional protein that contains a single HMA domain at the C-terminal (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Purified GSCS1 binds Ca2+ in vitro with a high affinity; its Kd value is comparable to that of the C2 domain Ca2+ sensor ROD1 (Kd = 0.4 µM)37 and more than an order of magnitude lower than those of the Arabidopsis calmodulin AtCaM1 (Kd = 5.6–20 µM)38, soybean CaM1 (Kd = 5 µM)39, and calmodulin-like protein CML14 (Kd = 12 µM)40. Using heterologous expression assays in yeasts, E. coli inverted vesicles, and Xenopus oocytes, we demonstrated that GCSC1 exhibits a Ca2+ transport activity (Fig. 4b–i). In fact, the inward currents of oocytes expressing GCSC1 were stronger than those expressing the A. thaliana Ca2+-permeable channel AtCNGC1421,41. However, we were not able to detect the Ca2+ transport activity of GCSC1 in an artificial bilayer system, suggesting that GCSC1 might function either as a Ca2+-permeable channel or a Ca2+ flux modulator. The protein sequence of GCSC1 shows no similarity to any canonical Ca2+-permeable channels in plants, including CNGCs, GLR, MCUs, and CSCs/OSCAs10,42. Although GCSC1 contains a HMA domain, which is present in some members of P-type ATPase protein family43, GCSC1 lacks any of the four principal domains of P-type ATPase, the actuator domain, the phosphorylation domain, the nucleotide-binding domain, and the transmembrane domain. In fact, except for the HMA domain, no conserved domain could be identified in other protein regions of GSCS1 (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Therefore, we propose that GCSC1 more likely functions as a Ca2+ flux modulator to mediate the Ca2+ flux across chloroplast and cytosol. GSCS1 could form homodimer and homotetramer (Fig. 6c); it is possible that these homo-oligomers mediate Ca2+ transport. Recently, several noncanonical Ca2+-permeable channels have been identified in plants, including the A. thaliana CNL receptor ZAR1 and wheat CNL receptor Sr35 which could be form pentameric resistosomes and target to plasma membrane to mediate Ca2+ influx as Ca2+-permeable channels44,45,46, and the tetrameric CNL-Like helpers ADR1 and NRG1.1 that were enriched in plasma membrane puncta to assemble Ca2+-permeable cation channels to mediate cytosolic Ca2+ influx47,48.

Unlike the plasma membrane-localized noncanonical Ca2+-permeable channels involved in immune response, GCSC1 is mainly localized to the chloroplast vesicles (Fig. 3d–g; Supplementary Fig. 14a, b) and functions in efflux of Ca2+ from the chloroplasts to the cytosol (Fig. 5a–j). The cytosolic Ca2+ level is maintained by fluxes of Ca2+ between the cytosol and apoplast as well as the intracellular compartments such as vacuole, ER, and chloroplast10,42,49, which requires various Ca2+ channels or transporters (Fig. 8k). Chloroplast has long been considered to be a potential Ca storage compartment as it accumulates as much as 15–25 mM Ca2+ in comparison to the nanomolar level in the cytosol50. The Ca uniporter cMCU and Ca2+ transporter BICAT have been shown to mediate the Ca2+ influx into chloroplast11,12. Knockout of GCSC1 results in reduction of Ca2+ efflux from chloroplast and more Ca2+ accumulation in chloroplast (Fig. 5a–j), indicating that GCSC1 functions in efflux of Ca2+ from the chloroplasts to the cytosol. GCSC1 is mainly localized to the chloroplast vesicles (Fig. 3d–g; Supplementary Fig. 14a, b), which can be invaginated from and fusion into the chloroplast inner envelope membrane. Chloroplast vesicles are believed to play important roles in delivery of lipids and proteins from the inner envelope membrane to thylakoid membrane16,18. The chloroplast vesicle traffic may also be involved in shuttling Ca2+ between the inner envelope membrane and thylakoid membrane as a large proportion of Ca2+ in the chloroplast is bound to the negatively charged thylakoid membrane51. Therefore, GCSC1 is involved in Ca2+ efflux from the chloroplasts to the cytosol via chloroplast vesicle traffic, thus playing an important role in maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis in plant cells (Fig. 8k).

It is well known that transpiration is a key factor controlling Ca distribution in plants30. Suppression of transpiration in leaves is known to reduce the accumulation of Ca in the transpiring leaf tissues and meanwhile enhance the allocation of Ca to the organs with a low transpiration, such as seeds and fruits30,52. The node I in rice is a transport hub that controls the flow of nutrients and water towards the flag leaf or the panicle during the grain filling53. The enlargement of the vascular bundles in the node slows down the flow toward the flag leaf, thus facilitating the flow toward the panicle. In general, a slower flow to the flag leaf allows relatively more to be distributed to the panicle. Knockout of GCSC1 led to reduced stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, and water loss in flag leaves (Fig. 7d–h). Therefore, the higher level of Ca in the grains of gcsc1 can be explained by a reduction in the transpiration rate in flag leaves which reduces the Ca flow to flag leaves, and allows more Ca to be allocated to grains (Fig. 8k). The Ca2+ and ROS signaling play a crucial role in regulating stomatal opening9,54,55. Disruption of Ca homeostasis in the chloroplasts has been shown to alter the stomatal aperture11,56,57. Knockout of Arabidopsis thylakoid membrane-localized Ca2+ sensing receptor CAS reduced cytosolic Ca2+ transients and altered the stomatal closure56,57. The cMCU knockout also lead to constitutive reduction in stomata opening and enhanced resistance to long-term water deficit11. Knockout of GCSC1 not only altered the cytosolic/chloroplast Ca2+ balance, but also affected the expression of several genes involved in generation and scavenge of ROS (Supplementary Data 2), which leads to more ROS accumulation in guard cells and promotes the stomata closure (Fig. 7i–l). The diurnal pattern of GCSC1 expression in leaves (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. 11b) is also consistent with a role of GCSC1 in regulating stomatal opening.

In summary, we have identified GCSC1 as the causal gene underlying a QTL for Ca accumulation in rice grains. CGSC1 encodes a function unknown HMA domain-containing protein that is localized to the chloroplast vesicle and mediates Ca2+ efflux from the chloroplasts to the cytosol. Knockout of GCSC1 results in elevation of Ca level in the chloroplasts and a reduction of transpiration rate in flag leaves, thus allowing more Ca to be allocated to grains. We also identified the elite GCSC1 haplotype from rice germplasms which is associated with higher Ca concentration in grains. The identification of natural variation at the GCSC1 loci provides an efficient way to breed rice varieties with higher levels of Ca in the grains, thus contributing to solving global Ca deficiency.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The recombinant inbred lines (LT-RILs) and “TeQing”-into-“Lemont” backcross introgression lines (TILs) were derived from crosses between “Lemont” (LM, Geng/japonica) and “TeQing” (TQ, Xian/indica) as described previously13,15,58. Near isogenic lines (NILs) were generated by crossing the RIL containing the LM genomic fragment at the qGCa3 locus with TQ and continued backcrossing with TQ. The NILs in TQ background and containing the genomic fragment from TQ or LM, respectively, at the qGCa3 locus, were chosen at BC3F2 generation by marker-assisted selection. The knockout mutants of GCSC1 were created via CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology59. Two target editing sites were selected within the first exon of GCSC1. The primers used for vector construction are listed in Supplementary Data 4.

The growth of LT-RIL and TIL populations in the paddy field for harvesting grains for QTL mapping was described previously13. The NILs, and recombinant lines for fine mapping were grown in the paddy field in Hunan province or Hainan province, China, to produce seeds for grain ionomic profiling analysis. For elemental analysis of the WT and gcsc1 mutants and gene expression analysis at seedling stage, rice seedlings were grown hydroponically with half-strength Kimura B solution according to previous studies15,58. Plants were grown in a closed greenhouse with a setup of 12-h light (26–28 °C)/12 h dark (22 °C) photoperiod, 50–60% relative humidity and approximately 700 mmol m−2 s−1 light. For examining the Ca remobilization in gcsc1, plants were grown hydroponically with half-strength Kimura B solution containing various concentrations of Ca, and the nutrient solution was renewed every 3 days.

QTL analysis and fine mapping of qGCa3

The QTL analyses of LT-RILs and TILs population using restriction length polymorphism (RFLP) and simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers, respectively, were performed using Windows QTL cartographer version 2.5 (http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm) according to our previous studies15,58. For QTL analyses of LT-RILs using the bin markers, the whole genome of LT-RILs was resequenced and the QTL analyses were performed using the R/qtl package60 as described previously14. For fine mapping of qGCa3, the RIL containing the LM genomic fragment at the qGCa3 locus was crossed with TQ and backcrossed with TQ again to generate the BC2F1. The BC2F2 population was generated by self-pollination. Two markers, L14212 and L22000, were developed and used to detect the recombination events occurred between these two markers that covered the qGCa3 locus. Additional 6 molecular markers were developed for fine mapping. Six recombinants were isolated from 1332 BC2F2 plants and the fixed recombinant BC2F2;4 plants for determining grain Ca/Sr concentrations were generated by two rounds of self-pollination. qGCa3 was fine mapped between the markers L15406 and L15525 by progeny testing. The markers shown in Fig. 1e were also used to determine the genotype of the paired recombinant lines for the progeny testing. The primer sequences used for fine mapping are listed in Supplementary Data 4.

Tissue elemental analysis and microfocus X-ray fluorescence (µ-XRF) scanning

The concentrations of Ca and Sr in grains of LT-RILs and TILs for QTL analysis were determined using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) (Elan DRCe, PerkinElmer Corp., USA) as described previously13,15,58. For quantification of elemental concentrations in grains of NILs, WT, and gcsc1 mutants, 6–12 seeds at the top of the panicle were collected and manually dehusked and digested with pure HNO3 according to previous studies58,61. The elemental concentrations were determined using an ICP-MS (NexION 300D, PerkinElmer Corp., USA). The Ca concentration in grains was also determined by an atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS, PinAAcle 900T, PerkinElmer Corp., USA). For determination of Ca and Sr in roots and different leaves of WT and gcsc1, plants were grown hydroponically with modified half strength solution Kimura B solution containing 1.8, 18, 180, 900, or 1800 μM CaCl2 for 18 days (solution refreshed every 3 d). The SrCl2 was then added to the nutrient solution to a final concentration of 0.5 μM and kept growing for 3 days. Roots and different leaves were excised and washed three times with Milli-Q water, dried overnight at 65 °C, and digested with HNO3 before elemental concentrations were determined using a NexION 300D ICP-MS.

To determine the effect of GCSC1 knockout on the allocation of Ca in mature leaves and newly developed leaves in the vegetative stage, WT, and gcsc1 plants were cultured hydroponically with standard half-strength Kimura B solution containing 180 μM Ca(NO3)2 for 32 days. Half of plants were then transferred to nutrient solution containing 1.8 μM Ca(NO3)2 and kept growing until one new leaf fully emerged. The other half of plants continued growing in half-strength Kimura B solution containing 180 μM Ca(NO3)2 as control. The upmost fully expanded leave before treatment was marked as the mature leave. The fresh weight of new leaves was measured after the treatment. The Ca concentration in the mature and new leaves was determined by ICP-MS as described above.

To determine the grain Ca concentration, grains of WT and gcsc1 were attached to a Kapton tape using a plastic tweezer and then scanned on an X-ray fluorescence (µ-XRF) spectrometer (M4 TORNADO Micro-XRF spectrometer, Bruker, Germany). The relative fluorescence intensities of µ-XRF images were quantified using ImageJ v1.8.0 (https://imagej.net/imagej-wiki-static/Fiji/Downloads).

Measurement of water loss, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate

The measurement of water loss and stomatal conductance were conducted according to previous studies with modifications61. For measurement of water loss of leaves from the plants at seedling stage, the second fully expanded leaf counting from the top of four-week-old plants grown hydroponically were detached and kept on a bench in ambient laboratory conditions. For measurement of water loss of flag leaves from the plants at grain filling stage, plants were grown in a greenhouse until flowering. At appreciate 10 d after flowering, the flag leaves were detached and the fresh weight was recorded at various time points. Water loss was expressed as the percentage of initial fresh weight. The stomatal conductance and transpiration rate were measured on the flag leaves of WT and gcsc1 plants grown in a paddy field using a portable gas analysis system (LI-COR 6800, LI-COR Inc.). The measurement was performed under the following conditions: a constant water concentration of 35.19 ± 4.58 mmol mol−1, a constant temperature of 32.28 ± 1.58 °C, and a constant CO2 concentration of 395.49 ± 2.22 mL L−1.

Stomata imaging and detection of ROS in guard cells

For imaging intact status of stomata, the second fully expanded leaves of 4-week-old WT and gcsc1 grown hydroponically were cut and immediately fixed by liquid nitrogen. The stomatal pictures were obtained in the middle leaves using an environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM, QuattroS, ThermoFisher). The ROS level in guard cells was detected by staining with a fluorescence dye H2DCFDA according to previous studies62. The second fully expanded leaves of 4-week-old rice seedlings were cut and immediately immerged in 0.01% Tween-20 and vacuum-infiltrated for 5 min. After rinsing twice with distilled water, leaves were incubated in 2% (w/v) cellulase RS (Yakult) for 5 h at 40 °C without shaking to facilitate peeling off the epidermal strips. The epidermal strips were peeled off from leaves. After washing with loading buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl at pH 7.2), the epidermal strips were incubated in staining buffer (loading buffer containing 50 mM H2DCFDA) for 12 min at room temperature in the dark. The epidermal strips were washed with distilled water to remove the excess dye. The fluorescence was examined using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica SP8) with the following settings: excitation, 488 nm; emission, 525 nm and power, 15%. For quantifying the gray value in the guard cells, the guard cells region was selected and the mean gray value was recorded using ImageJ.

Genetic and transgenic complementation test

For transgenic complementation experiment, the gcsc1 knockout mutant was transformed with the genomic sequence of GCSC1 from LM and fusion in frame with GFP. The promoter sequence, full-length genomic sequence and 3′-untranslation region (UTR) sequence of GCSC1 and GFP were PCR amplified separately using the primers listed in Supplementary Data 4. The correct PCR fragments were confirmed by Sanger sequencing and were ligated into the BamHI-HindIII site of pCAMBIA1301 vector to generate the GCSC1pro::GCSC1-eGFP-3’UTR construct. After being sequenced for confirmation, the resulting plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 and introduced into gcsc1 as described previously15. For genetic complementation, two independent lines of gcsc1 were crossed with NIL(TQ) and NIL(LM). The WT was also crossed with NIL(TQ) and NIL(LM) as controls. The grain Ca and Sr concentrations in grains of F1 plants were determined using ICP-MS.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative reverse transcription PCR

To investigate the expression of GCSC1 in NIL(TQ) and NIL(LM), the shoots, roots, and basal nods were harvested from 4-week-old plants grown in half-strength Kimura B solution. Different tissues of TQ and LM grown in a paddy field were collected to determine the expression pattern of GCSC1 at different growth stages. To determine the rhythmic expression of GCSC1, the leaf blades of TQ and LM seedlings grown in half-strength Kimura B solution were sampled with 2 h interval for 2 d. Total RNA was extracted using a total RNA extraction kit (RP3301, Bioteke), and then treated with RNase-free DNase to remove potential genomic DNA contamination. The cDNA synthesis was carried out using HiScript II Q Select RT SuperMix (R233, Vazyme). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed on a Real-Time PCR System (CFX96, BIO-RAD) with AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master MIX (Q111, Vazyme). The ΔCt method was used for calculating the relative expression of GCSC1 with rice OsActin gene as internal control. The primer sequences were listed in Supplementary Data 4.

Genome-wide transcriptomic analysis

The flag leaves of WT and gcsc1 plants grown a in paddy field were harvested for Genome-wide transcriptomic analysis. Total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality and integrity were assessed on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and checked using RNase free agarose gel electrophoresis. The mRNA was enriched by Oligo(dT) beads and transcribed into cDNA by using NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB #7530, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The resulting cDNA library was sequenced using Illumina Novaseq6000. The raw reads were filtered to obtain high-quality reads by removing adapter sequences and low-quality reads (containing over 10% of N or trim the ends of reads with low sequencing quality (<Q20)). The clean reads were aligned to the Nipponbare reference genome (version 4). An index of the reference genome was built, and paired-end clean reads were mapped to the reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.0.4). The mapped reads of each sample were assembled by using StringTie (v1.3.1) in a reference-based approach. For each transcription region, a FPKM (fragment per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) value was calculated to quantify its expression abundance and variations, using RSEM software (v1.3.3). RNAs differential expression analysis was performed by DESeq2 (v1.4.4) between two different groups and by edgeR (v4.2.1) between two samples. The genes with the parameter of false discovery rate (FDR) below 0.05 and absolute fold change≥2 were considered differentially expressed genes. For GO enrichment analysis, all differential expression genes (DEGs) were mapped to GO terms in the Gene Ontology database (http://www.geneontology.org/), gene numbers were calculated for every term, significantly enriched GO terms in DEGs comparing to the genome background were defined by hypergeometric test. The calculated p-value were gone through FDR correction with FDR ≤ 0.05 as a threshold.

Tissue expression pattern and subcellular localization of GCSC1

To investigate the tissue expression pattern of GCSC1, leaves of GCSC1pro::GCSC1-eGFP-3’UTR transgenic plants were cut into sections by hand sectioning, and then were examined using a Two-photon laser scanning microscope (Olympus FV1000 MPE) equipped with a 500–550 nm barrier filter to detect GFP fluorescence and a 650–710 nm barrier filter to detect chlorophyll autofluorescence. To investigate the subcellular location of GCSC1, the full-length coding sequence of GCSC1 was amplified from cDNA synthesized from LM using primers listed in Supplementary Data 4 and ligated into the KpnI–SacI site of p1301GFP vector61 to create the UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP construct. The correct construct confirmed by Sanger sequencing was transformed into rice variety Zhonghua11 using Agrobacteria-mediated transformation method as described above. Protoplasts were prepared from the leaf sheaths of UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic plants. The GFP fluorescence and chlorophyll autofluorescence were examined using a Two-photon laser scanning microscope (Olympus FV1000 MPE) as mentioned above.

Immunogold labeling and transmission electron microscope

For immunogold labeling analysis, young leaves were detached from 3-week-old UBI::GCSC1-GFP transgenic plants grown under half-strength Kimura B solution. Detection of immunogold labeling signals was performed as described previously with modifications62. The leaf sections were fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.2, and stored at 4 °C overnight. Section samples were fixed in 2% (w/v) osmium tetroxide in PBS for 1 h at room temperature after washing three times with PBS. After three rinses in MilliQ water, samples were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and slowly infiltrated with LR White resin over several days. Sectioning was performed using a Leica Ultracut R microtome with a diamond knife and 80-nm-thick sections were collected on formvar-coated gold grids. Ultrathin sections were exposed to 10% H2O2 for 10 min. After washing in distilled water three times, the sections were blocked in 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The grids were incubated with anti-GFP (ab6556, Abcom) at 4 °C overnight. Following three washes in 1× PBST, grids were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG (whole molecule 5 nm colloidal gold) antibody (G7277, Sigma) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing three times with 1× PBST and distilled water, the grids were stained with 2 min of 2 % (w/v) aqueous uranyl acetate and 2 min of lead citrate. The grids were dried at room temperature and examined with a transmission electron microscope (HT7800, Hitachi) using a voltage of 80 kV.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

To confirm the location of CGSC1 to chloroplast but not to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, total protein was extracted from intact chloroplast or ER, respectively, and western blot analysis was performed on purified proteins. Chloroplast proteins were extracted according to previous studies with modifications63,64. Briefly, leaves of four-week-old UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP or UBIpro::GFP transgenic plants were homogenized in a blender on ice with pre-cold isolation buffer (50 mM HEPES/KOH, 0.3 M Sorbitol, 5 mM Ascorbate, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.6). The homogenate was then filtered through 3 layers of miracloth (475855, Millipore) and centrifuged at 1500 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended using isolation buffer and centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was then resuspended in 1 ml isolation buffer, and placed on top of Percoll gradients by underlying 4 ml 10% Percoll (2 ml 2× isolation buffer, 0.4 ml Percoll, 1.6 ml H2O), 3 ml 30% Percoll (1.5 ml 2× isolation buffer, 0.9 ml Percoll, 0.6 ml H2O), 3 ml 50% Percoll (1.5 ml 2× isolation buffer, 1.5 ml Percoll, 0 ml H2O). Samples were centrifuged at 8000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C. Intact chloroplasts between 30 and 50% Percoll were collected after removal of broken chloroplasts by a syringe. Intact chloroplasts were washed twice using isolation buffer by centrifugation for 5 min at 10,000 × g and 4 °C. Collected chloroplasts were boiled in SDS loading buffer before western blot analysis.

The ER membrane proteins were isolated as previously described65,66. Briefly, leaves of four-week-old UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP transgenic plants were harvested and homogenized in a blender on ice with pre-cold homogenization buffer (500 mM sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, and 150 mM Tricine-KOH, pH 7.5). The homogenate was filtered through 3 layers of miracloth (475855, Millipore), and the filtrate was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was placed on the top of sucrose gradients by underlying 5 ml of 30% sucrose and 3 ml of 20% sucrose, then centrifugation and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4 °C. The ER membrane between the 20% to 30% sucrose interface was carefully collected with a syringe and boiled in SDS loading buffer before western blot analysis. Total protein was extracted from leaves as control using a Plant Protein Extraction Kit (CW0885, Cwbio).

The chloroplast membrane proteins were extracted by using two methods with different pH values. Intact chloroplasts were prepared from leaves of four-week-old UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP or UBIpro::GFP transgenic plants as described above. The intact chloroplasts were then lysed by incubation on ice for 30 min in an alkaline solution (100 mM Na2CO3, pH 11.5), or by hypotonic shock at −80 °C following by resuspension in a suspension buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, 4 mM MgCl2, pH 8). The lysis was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C to yield the pellet of chloroplast membranes. The supernatant fraction containing soluble stromal proteins was kept for western blot analysis. The membrane pellets were washed with the alkaline solution or the suspension buffer, respectively, and were then resuspended in a protein extraction buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.45, 8% SDS, 1 mM EDTA) before western blot analysis. Total chloroplast protein extracted by the protein extraction buffer from intact chloroplasts was used as a control.

For western blot analysis, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P Transfer membranes, IPVH00010, Millipore). The membranes were incubated with the purified primary rabbit anti-GFP antibody (ab6556, Abcom), anti-UGPase (AS05086, Agrisera), anti-psbB (CP47) antibody (PHY0319, PhytoAB), anti-Rbisco large subunit form I and form II (RbcL) (AS03037, Agrisera), anti-biding immunoglobulin protein (BIP2) (AS09481, Agrisera). Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L)-HRP (AT0097, CMCTAG) was used as a secondary antibody, and an ECL Pico-Detect Western Blotting Substrate (IF6747, CMCTAG) was used for detection via chemiluminescence (Bio-Rad).

LC-MS/MS

The subcellular location of GCSC1 was also investigated by fractionation of chloroplast membrane and stromal proteins and determined by LC-MS/MS. Three leaves of different WT Zhonghua11 plants grown in a paddy field were harvested for chloroplasts isolation as described above. Intact chloroplasts were lysed by hypotonic shock and resuspensed in suspension buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, 4 mM MgCl2, pH 8), followed by incubation on ice for 10 min. The lysis was frozen at −80 °C overnight. The chloroplast lysis was centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C to yield the soluble stromal fraction and a pellet of chloroplast membranes.

The presence of GCSC1 protein in the stromal and membrane fractions were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. The samples were reacted with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 56 °C for 30 min and 55 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) at room temperature for 30 min in darkness. For protein digestion, the protein solution was enzymatically hydrolyzed with trypsin and 100 mM TEAB at 37 °C for 4 h, then was maintained with trypsin. Peptides were desalted using C18 column, vacuum-dried. Digested peptides in 0.1% formic acid, 2% acetonitrile were loaded on an Eskigent nano-UPLC system (Ekspert NanoLC, AB SCIEX) coupled to a Hybrid Q-TOF mass spectrometer (TripleTOFTM 5600-plus, AB SCIEX). The polypeptide solution was applied to a C18 trap column (5 μm, 100 μm × 20 mm) and subjected to gradient elution in a C18 analytical column (3 μm, 75 μm × 150 mm) at a flow rate of 300 nL min−1 over a 90 min time gradient using the two mobile phases buffer A (2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, 98% H2O) and buffer B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, 2% H2O). For information-dependent acquisition, a first-order mass spectrum scan was performed using an ion accumulation time of 250 ms, and 40 precursor ion secondary spectra were acquired with an ion accumulation time of 50 ms. MS1 spectra were acquired in the range of 350−1500 m/z, and MS2 spectra were acquired in the range of 100−1500 m/z. The time for precursor ion dynamic exclusion was set to 15 s. The mass spectrometry analysis was performed using Proteinpilot software (v5.0.2) for protein identification and quantification with setting of conf ≥ 95% and unique peptide number ≥ 1.

Microscale thermophoresis (MST) assay

The CGSC1-GFP fusion protein and GFP protein purified from the UBIpro::GCSC1-GFP and UBIpro::GFP transgenic plants, respectively, were used for microscale thermophoresis (MST) assay. Total proteins were extracted from shoots of three-week-old seedlings in ice cold IP buffer 1 (50 mM Tris‐HCl pH7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, Protease inhibitor cocktail (P9599, Sigma)) and purified using GFP-Trap beads (gta-20, Chromotek) according to the product manual. The purified GFP and GCSC1-GFP proteins were diluted in the MST buffer [0.2 M glycine: 1 M Tris base (pH 10.4) = 10: 1, 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 and 1 mg/ml BSA]. 20 μL of the highest concentration CaCl2 (40 μM) in MST buffer was filled into the first tube, and 10 μL of MST buffer was filled into the micro reaction tubes 2 to 15. 10 μL of tube 1 was transferred to tube 2 and mix well by pipetting up and down several times. A serial dilution was obtained by repeating this procedure and removed 10 μL from the last tube after mixing. For binding test, 10 μL of GFP (600 nM) or GCSC1-GFP (600 nM) proteins were mixed with 10 μL of calcium ion (CaCl2). After slight centrifugation, samples were loaded into standard capillaries. A range of concentrations of calcium ion (CaCl2) were diluted serially from 20 μM to 1.22 nM. The final concentration of GFP or GCSC1-GFP proteins were 300 nM. Thermophoresis was performed in a Nanotemper Monolith NT. 115 apparatus (NanoTemper Technologies). The binding affinities were calculated using MO. Affinity Analysis software.

Ca2+ transport activity assays in yeast

To determine the Ca2+ transport activity, the coding sequence of GCSC1 was amplified from LM or TQ cDNA using the primers listed in Supplementary Data 4 and then introduced into the KpnI–XbaI site of pYES2 vector. The correct constructs confirmed by sequencing were transformed into an excess Ca sensitive yeast mutant strain k667, which lacks the vacuolar Ca2+-ATPase PMC1 and vacuolar Ca2+/H+ antiporter VCX167, using a Frozen EZ Yeast Transformation II kit (T2001, ZYMO RESEARCH). Yeast transformants were selected on synthetic medium lacking uracil (SD-U). For the plate experiment, four serial tenfold dilutions of yeast cultures were spotted on the SD-U medium containing 2% glucose or galactose with 0, 10, 20, 80 mM CaCl2 and incubated at 30 °C for 3 d. For the liquid proliferation test, yeast cells were washed with Milli-Q water for three times, and the O.D.600 was adjusted to 0.01 in 30 ml of liquid SD-U medium containing 0 or 5 mM CaCl2. The O.D.600 was monitored at indicated times for 60 h. For measurement of Ca content in yeast cells, yeast strains carrying GCSC1 or an empty vector (pYES2) were cultured to log phase in liquid SD-U medium containing 2% galactose. After washing three times with ice-cold Milli-Q water, the yeast cells were collected and digested for Ca determination by ICP–MS.

Ca2+ transport assays in everted membrane vesicles

The Ca2+ transport activity of GCSC1 in everted membrane vesicles were performed as described previously with modificatioins68. Briefly, the coding sequence of GCSC1 was amplified from LM or TQ cDNA using the primers listed in Supplementary Data 4. The correct PCR products confirmed by sequencing were introduced into the SacI–KpnI site of pTrcHis2A vector. The correct constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli (E.coli) strain Rosetta 4 mM MgSO4, 2 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF were added to the suspension, to improve the membrane quality. The cells were then disrupted through high-pressure cell disrupter (JN-Mini, JNBIO) at 4 °C. The lysate was collected in a tube suspended in ice water. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifuged at 8000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant solution was centrifuged at 150,000 × g at 4 °C for at least 1 h to pelletize membrane vesicles. The pelleted membranes are suspended in buffer B (75 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 0.15 M K2SO4, 1 mM MgSO4, and 250 mM sucrose) to a final concentration of approximately 10 mg/mL membrane vesicles.

For Ca transport activity assays in everted vesicles, Ca uptake was started by the addition of 50 mM CaCl2 to 1 mL everted vesicles suspended in buffer B, and the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Each assay contained 10 mg/mL everted membrane vesicles and 50 mM CaCl2. The everted membrane vesicles were then filtered through 0.22 μm pore size nitrocellulose filters and transferred to the buffer B without Ca for Ca exclusion. After 15 min incubation, each sample was filtered through mixed cellulose esters (MCE) membrane filters with 0.22 μm pore size, and washed twice with 5 mL of the same buffer. Ca content was determined by AAS (PinAAcle 900 T, PerkinElmer Corp., USA).

Two-electrode voltage clamping