Abstract

Unintentional releases of rare earth elements (REEs), emerging environmental pollutants, from global industries contribute to atmospheric pollution. However, a gap remains regarding the recognition of REYs in industrial fine particulate matter (PM) as a primary source of atmospheric PM. Here, we identified the characteristic of REEs in PM from 114 large-scale industries covering 13 important sectors. Based on the derived emission factors, 13 industrial sources in China emit 136,914 kg of REEs annually, with cement, coal power and coking responsible for 105,226, 12,635, and 11,940 kg/year, respectively. Source-specific elemental profiles were achieved and can be used to allocate the sources of REEs in atmosphere. The average daily intake of REEs from industrial fine PM inhalation was 11.72 ng/(kg·day) for children and 7.41 ng/(kg·day) for adults, pivotal data for assessing health risks. This study is important for sustainable industrial development and human wellness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rare earth elements (REEs) in the environment are considered as emerging pollutants1,2. REEs are widely used in many industries and thus led to a significant increase in their environmental releases, exceeding allowable limits in the atmosphere occasionally3. Atmospheric particulate matter (PM) is small, particularly PM2.5 and/or PM1.0 can easily enter the alveoli, and harmful substances enriched in PM such as heavy metals and organic contaminant considerably magnify its risk, but REEs have long been neglected. The sharp increase in the migration and enrichment of REEs in the atmosphere3,4, water5,6 and soil7 not only disrupts the balance of natural ecosystems but also has toxic effects on microorganisms, plants and animals. REEs exhibit environmental behavior similar to heavy metals, capable of accumulating in organisms and producing an excitatory effect that is promotive at low doses and inhibitory at high doses, thus posing potential ecological risks5. Moreover, animal studies and human occupational exposure indicate that REEs can induce a variety of health complications, including respiratory issues, oxidative stress, liver, lungs and kidneys tissue damage, as well as neurological damage8. REE ions can enter the brain tissue, accumulate and produce neurotoxicity9. Occupational exposure to REEs may increase the risk of pneumoconiosis and eventually lead to pulmonary fibrosis10. The inhalation of REEs loaded on PM10 can lead to a decrease in the activity of human lung epithelial cells, induce an increase in intracellular reactive oxygen species production and cause significant intracellular DNA damage11. The nLa2O3 and nEu2O3 nanoparticles at a concentration of 80 μg/ml could induce 75.1% and 53.6% of macrophages to produce toxicity and death, respectively12.

The emission of industrial activities contributes greatly to atmospheric PM2.513, which might lead to higher concentration of REEs in the atmosphere. REEs in PM not only threatens human health through the food chain, but also has multiple potential effects on the human body through direct inhalation and skin contact. Fly ash from coal-fired power plants (CFPP) is considered as REEs secondary resource14,15, which has attracted special attention from countries such as China16,17,18, the United States19,20,21,22, Europe23,24,25,26 and India27,28,29, etc. However, most of these studies mainly focus on the recovery potential of REEs, and the atmospheric emission of CFPP as a REEs pollution source is unclear. The occurrence, distribution and emission of REEs from other important industrial sources are even blank.

The long-distance migration of industrial fine PM will increase the risk of general population exposure. The concentration of REEs found in the atmosphere near the steel plant was significantly higher than that in the urban background site, indicating the potential impact of the steel industry on surrounding atmosphere and population health. It is noteworthy that the key question of how much these industrial emissions will increase the concentration of REEs in the atmosphere has been unsolved30. In order to reduce the environmental pollution and health hazards of REEs, it is necessary to analyze their sources and determine which industries produce more REEs and their related characteristics. At present, there is still a huge gap in the knowledge of REEs atmospheric emission inventories and population exposures generated by various important industrial activities.

Here, we focused on the REEs in PM from 13 industrial processes, including the coal-fired industry, which is the world’s primary source of power generation, as well as the iron and steel industry and nonferrous metal smelting industry, which are significant support for national economic development. We used inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to analyze the levels of REEs in various industrial PM, and then further estimated and mapped the annual emissions of REEs in 31 provinces of mainland China based on the emission factor (EF) and industrial production, and compared their spatial distribution differences. Finally, the population exposure due to the industrial emissions were evaluated. It is expected these results are important for sustainable industrial development and human wellness.

Results and discussion

REEs concentrations in multiple industrial fine PM

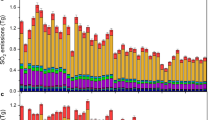

The REEs concentrations in fine PM from 13 industries are shown in Fig. 1a. The individual REE concentration and detailed data are given in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1. The concentration of REEs varies significantly, ranging from 1–2 orders of magnitude among 13 industrial sources, and is 2–3 orders of magnitude lower compared to the common metal elements (Fe, Zn, Al, etc.)31. The highest REEs concentration (434.02 μg/g) and the highest average REEs concentration (240.89 μg/g) in all PM samples were found in CFPP. The REEs concentration of CFPP-2 is the highest, exceeding the world average concentration (403.5 µg/g)32. The REEs concentrations of CFPP-8, CFPP-11, CFPP-4 and CFPP-16 were also high, which were 345.21, 310.88, 306.37 and 303.48 μg/g, respectively. The high melting point of REE makes most REE-containing minerals difficult to decompose during coal combustion and remain in coal ash33,34. The concentration of REEs in coal fly ash will be enriched by 6–10 times14,15,35, and the concentration of individual REE may be about 10–15 times that of raw coal36. The REEs concentrations in 12 PM from CFPP were above 200 μg/g, which were significantly higher than that in Xiamen (12.07–98.45 μg/g)37, and that in Quanzhou’s industrial area, residential area, economic area and agricultural area (209.4, 140.1, 171.7 and 119.9 μg/g, respectively)38. However, there was also a PM sample with a very low REEs concentration (6.10 μg/g). It can be seen that coal from different geological sources affects the level of REEs in PM from CFPP39.

a The REEs concentrations in fine PM from 13 industrial sectors. b Distribution of light REEs (LREEs), medium REEs (MREEs) and heavy REEs (HREEs) in industrial PM samples. LREEs = (La + Ce + Pr + Nd + Sm), MREEs = (Eu + Gd + Tb + Dy + Y), HREEs = (Ho + Er + Tm + Yb + Lu); Critical REEs = (Nd + Eu + Tb + Dy + Er + Y); BFI blast-furnace pig iron, CFPP coal-fired power plant, CK cement kiln co-processing solid waste, COP coking plant, EAF electric-arc furnace steelmaking, HWI hazardous-waste incineration, IOS iron-ore sintering, PCu Primary copper smelting, SAl secondary aluminum smelting, SCu secondary copper smelting, SPb secondary lead smelting, SZn secondary zinc smelting, WI municipal solid-waste incineration.

Relatively high REEs concentrations were found in PM from blast-furnace pig iron (BFI), coking plant (COP), secondary zinc smelting (SZn), municipal solid-waste incineration (WI) and hazardous-waste incineration (HWI), with an average concentration range of 48.14 (±78.21) μg/g to 88.98 (±137.37) μg/g. These important emission sources of REEs have been neglected in previous studies. At least two PM samples from BFI and SZn contained more than 60 μg/g REEs, and even one up to 367.72 and 287.65 μg/g, respectively. Iron ore and coke raw materials may contain a small amount of REEs, which will be extracted together with other metals and eventually partially enriched in PM in the process of BFI. SZn has the highest mean REEs concentration among the secondary metal smelting industry, which may be due to the presence of REEs in some zinc-containing wastes and the smelting process. The use of bituminous coal with a certain adhesion as a raw material may be the reason why the concentration of REEs in PM from COP is evenly distributed at an average of 53.61 μg/g. The domestic waste, industrial waste and electronic waste treated by WI may contain a variety of substances containing REEs. Due to the wide source of raw materials, the REEs concentration in four PM samples from WI exceeded 90 μg/g, which higher than that in Italy (54 μg/g), the remaining was mainly between 7 and 50 μg/g. In view of the frequent use of REEs in medical fields such as pharmaceutical reagents, laser materials and magnet manufacturing in recent years40. The high REEs content of HWI may be largely derived from medical waste, and its average concentration (48.14 μg/g) was similar to that in different medical WI fly ashes (45.23 μg/g) from four cities in China40. Industrial hazardous wastes such as metal mining and nonferrous metal smelting may also contain REEs.

Although the average concentration of REEs in PM from coal-fired power plant (CK), primary copper smelting (PCu) and secondary aluminum smelting (SAl) was nearly ten times lower than that from CFPP, they also showed a certain REEs pollution potential. In the process of aluminum smelting through the Bayer process, most REEs almost completely enter the bauxite residue, especially in red mud3. If red mud is comprehensively utilized as a raw material for CK and co-incineration of various REE-containing wastes, it is likely to cause REEs to be enriched in PM. The concentration of REEs in different PM from PCu and SAl varies greatly. For example, the REEs concentration of PCu-1 was as high as 108.29 μg/g, while that of PCu-2 was only 0.73 μg/g; SAl-3 had a high REEs concentration of 92.00 μg/g, while SAl-1 only contained 9.24 μg/g. The difference in raw materials and process may be the reason why PM emitted from electric-arc furnace steelmaking (EAF), iron-ore sintering (IOS), secondary lead smelting (SPb) and secondary copper smelting (SCu) contain less REEs. In particular, most of the individual REE concentrations in the PM from SPb were <0.05 μg/g, and Tb and Lu elements are almost undetectable.

For individual REE, REEs are often related to mineral phases such as discrete monazite [(Ce, La, Nd, Th)PO4] and xenotime [YPO4], especially the former is most detected35,41. Moreover, Ce, La and Nd are frequently added to alloys, optical fibers, ceramic/glass and polishing agents for the purpose to optimize material performance. Therefore, the content of Ce in all industrial PM was the highest, followed by La, Y and Nd. As shown in Fig. 1b, except for SPb, light REEs (LREEs) account for more than 70% of the total REEs content in other industrial PM, and the contents of medium REEs (MREEs) and heavy REEs (HREEs) are low. CFPP, BFI, COP, HWI and WI not only had relatively high REEs content, but also had >30% critical REEs with greater industrial value and demand, and the outlook coefficient Coutl > 0.7 (Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting their recycling potential, especially when the total amount of PM emitted by these industries is large. The recovery of REEs in industrial PM not only reduces environmental and health hazards, but also may alleviate the tight supply and demand situation of REEs.

Characteristics of REEs from multiple industrial sources

The identification and assessment of environmental pollutant sources have become one of the major challenges in pollution control. Industrial emissions are the main contributors to the total PM2.5 emissions in eastern Asia and even the world13. However, the analysis of industrial sources is not detailed enough, and it is usually simply categorized as industrial sources42. The lack of identification of various industrial sources will not be conducive to targeted and efficient pollution control and management. The composition and distribution of REEs in industrial PM are mostly unaffected by weathering, transport process, sedimentation and diagenesis, and the source information they carry is essentially unaltered, which is possible to track the source of pollutants43,44. Usually, the difference characteristic of REEs distribution patterns and some REEs parameters in environmental PM and pollution source PM is used to identify various pollution sources.

To compare the enrichment patterns of different elements in industrial PM, the REEs concentrations were normalized by upper continental crust (UCC). The geometric shape of the REEs distribution pattern has vital indicative significance, and distribution patterns showing high consistency typically indicate their common source attributes. As shown in Fig. 2, different REEs in PM have varying degrees of enrichment, and varies with different industrial types. According to the distinct enrichment degrees of LREEs, MREEs and HREEs, the UCC normalized REEs concentration was divided into L-type, M-type and H-type three types15. The PM from CK, COP, EAF, PCu, SAl and SZn enriched LREEs, which was L-type distribution (Fig. 2a). The distribution pattern of SAl is most consistent with the traditional L-type. The slope of the La–Sm segment curve is relatively large, and the Dy–Er segment curve is gentle, indicating that LREEs are enriched and the degree of differentiation is large, while MREEs are relatively depleted and the degree of differentiation is low. The different amplitudes of Gd positive anomalies and Y, Tb negative anomalies can be observed in these industries with L-type patterns. The anomaly of Gd and Y is based on the subtle difference in the stability of the REEs complex45. The SZn also shows a significant positive Eu anomaly, while SAl is just the opposite. The enrichment of Eu may be due to the fact that it is a redox-sensitive element, or it may be because of the replacement of Ca2+ with Eu2+ 46. The REEs in PM from BFI, CFPP, IOS and HWI belong to M-type distribution (Fig. 2b). The REEs distribution of CFPP is a typical M-type subtype, which is expansive and has no Eu anomaly15. One reason for the M-type distribution in coal may be that the adsorption of MREEs by humus is higher7. The REEs enriched in CFPP are about 1.2–1.9 times that of UCC, which may be attributed to the acidic hydrothermal solution providing REEs15. The obvious Gb enrichment in HWI is similar to that in different medical WI fly ashes40. The H-type distribution of REEs in PM includes WI, SCu and SPb (Fig. 2c). The Ho in WI samples is obviously enriched, which is different from the enrichment of Eu and Tb in Italian WI fly ash47. Unlike any other industrial PM, the REEs in PM from SCu have a clear Tb positive anomaly.

a Industries with UCC-standardized REEs concentration showing an L-type distribution [(La/Lu)N > 1]; b industries with UCC-standardized REEs concentration showing an M-type distribution [(La/Sm)N < 1] and [(Gd/Lu)N > 1]; c industries with UCC-standardized REEs concentration showing an H-type distribution [(La/Lu)N < 1].

We can also use the REEs-δEu diagram and the La-Ce-Sm ternary diagram for source apportionment. The source is identified based on the relative position of ambient PM and possible pollution source PM in the figure. In the REEs-δEu diagram, the PM from CFPP contain areas far away from other industrial sources (Fig. 3a). The areas of BFI, CK, COP, EAF, IOS, HWI and WI samples are overlapped, with the δEu is mainly in the range of 0.4–0.8. The distribution of PCu, SAl, SCu, SPb and SZn samples is more dispersed. In the La-Ce-Sm ternary diagram (Fig. 3b), the distribution of PM from SPb, SCu and WI is more dispersed, while other industrial sources overlap seriously. By using this method, it was identified that REEs in the atmosphere of all functional areas in Quanzhou were less affected by emissions from steel plants and cement plants. Vehicle exhaust and soil dust were primary sources, followed by CFPP38.

a The REEs-δEu diagram; b the La-Ce-Sm ternary diagram, which regards the sum of the three variables as a unit 1 and uses the percentage to represent the structural ratio of a single variable to the whole, and reflects the characteristics of the object according to the position information of the research object in the triangle diagram; c, d some REEs ratios characteristics in industrial particulate matter (PM) from 13 industries.

In order to further distinguish these industrial source characteristics, some REEs ratios in PM from various industrial activities were calculated and shown in Fig. 3c, d, including La/Sm, La/Ce, (La/Yb)N, (La/Eu)N, Ce/Nd, (Ce/Yb)N, (Gd/Yb)N and (Sm/Eu)N ratios. The REEs ratios in PM should be a more reliable long-range tracer43. PM emitted from SZn has higher (La/Yb)N, (La/Eu)N and (Ce/Yb)N ratios (average values: 34.14, 25.24 and 24.66) (Fig. 3c), which can be distinguished from other industrial emissions. The ratios of (La/Yb)N and (Ce/Yb)N in PM from HWI and SCu are the lowest, which are at least ten times lower than those from SZn. Ce/Nd ratio seems to be a characteristic index of SPb, which is as high as 47.06, while the values in other industrial PM are relatively low (Ce/Nd = 0.43–3.31). The La/Sm ratio in PM from SPb, CK, EAF and WI is about 3–7 times that of HWI, PCu, SAl and SZn (Fig. 3d). The La/Sm ratios of CFPP, BFI, COP, IOS and SCu samples are in the range of 5.95–7.13. The La/Sm ratio of the CFPP is similar to the reported in the previous study (5.2 ± 0.5), and has been proven to be one of the distinguishing indicators of industrial activities such as refineries, CFPP and transportation43. Based on the La/Ce and La/Sm ratios in atmospheric PM in Beijing, REEs were attributed to local soil and CFPP48. The La-Ce-Sm ternary diagram and the ΣREE vs δEu plot indicate a significant influence of other external pollution sources on the PM2.5 samples in Nanchang; the (La/Sm)N vs (Gd/Yb)N correlation plot further reveals that the samples are affected by both local sources and non-local sources such as coal combustion activities44. The Gd/Yb of EAF, PCu and CFPP are significantly higher than that of SAl and SCu. The (Sm/Eu)N shows the highest ratio of 5.13 in PCu, followed by SCu and SZn (3.02 and 2.71, respectively), and the HWI is only 0.25. It should be noted that these ratios may change with the change of PM particle size49. Previously, our report showed that CFPP emitted 79.3–83.4% of PM2.5, and PM2.5 emitted from other industries was as high as 97.9%50. In the process of pollution source identification, these methods are usually combined to obtain more accurate source apportionment results. Besides, the combination of REEs isotope fingerprinting methods, such as Nd-Pd-Sr multi-isotope technology, is also a powerful tracer and will also be the future trend of source identifications50,51.

Emission assessment of REEs from industrial fine PM and their regional disparity

We calculated the EFs of 13 industrial processes, and then quantified the primary emission of industrial source PM in 31 provinces of mainland China. These inventories provide important input for modeling the environmental fate, spatial and temporal distribution, and bioenvironmental effects of REEs in PM, and also facilitate the source control of environmental pollution. The sum of REEs annual emissions from 13 industrial sources is 136,914 kg, and the specific spatial distribution is shown in Fig. 4. Overall, industrial emissions in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and Guangdong Province contributed the most to REEs in the environment, followed by the central and eastern regions, while Tibet and Qinghai province accounted for only 0.80%. Shandong, Guangdong and Jiangsu provinces ranked in the top three, at 9688, 8821 and 8752 kg, respectively. Hebei, Anhui, Sichuan, Zhejiang, Henan, Yunnan and Shanxi provinces followed with the annual emissions of REEs exceeded 6000 kg.

ƩREEs the sum of REEs annual emission of 13 industries, BFI blast-furnace pig iron, CFPP coal-fired power plant, CK cement kiln co-processing solid waste, COP coking plant, EAF electric-arc furnace steelmaking, HWI hazardous-waste incineration, IOS iron-ore sintering, PCu primary copper smelting, SAl secondary aluminum smelting, SCu secondary copper smelting, SPb secondary lead smelting, SZn secondary zinc smelting, WI municipal solid-waste incineration.

From the perspective of each industrial source, the spatial distribution of REEs annual emissions in different provinces/cities is discussed in detail (Fig. 4), which is conducive to more accurate pollution control. The total amount of REEs emitted into the atmosphere in the form of fine PM by various industrial processes is different. Province-to-province variation in the amount of REEs emitted from the same industrial source. Despite the fact that the concentration of REEs in PM from CK is low. Based on total production (Supplementary Table 2) and high EF (Supplementary Table 3), CK has become the most important industrial source of REEs, with REEs emission of 105,226 kg (76.86%). CK in Sichuan, Yunnan, Guangdong, Shandong, Anhui, Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces has emitted a large amount of REEs, ranging from 5827 to 75,433 kg. Apart from Tibet and Qinghai province, CK emissions in other provinces are all above 500 kg, making them non-negligible. CFPP accounts for the majority of China’s thermal power generation, and about 67% of electricity came from coal combustion in 201852. According to our statistics, the coal use of CFPP is about 655,621 million tons, the highest of 13 industrial sources. However, REEs emission from CFPP is just 12,635 kg, which is one order of magnitude lower than CK because its EF is the lowest. The top three provinces of CFPP emissions contributing to REEs are Shandong, Inner Mongolia and Jiangsu provinces, with 1219, 1148 and 1051 kg, respectively. The main reason may be that the development degree of coal resources in Shandong and Jiangsu provinces is relatively high, and Inner Mongolia is the concentrated distribution area of large coal bases in China53. With a REEs emission of 11,940 kg, COP is second only to CFPP. This is because there are several processes of PM emission, including coal loading, coke unloading, coke oven heating and coke dry quenching (Supplementary Table 3), which lead to a larger total EF of PM from COP. Shanxi province (as the largest coke province in China) contributed highest, which is nearly 1/4 of the annual emission of REEs in China. BFI is also an important source, emitting 3525 kg of REEs to the environment annually, which can be attributed to its relatively high yield (889 million tons). Hebei province has the highest emission, followed by Shandong, Shanxi, Liaoning and Jiangsu provinces. Similarly, although the REEs concentration in PM from EAF is low, the higher production (1065 million tons) lead to a REEs emission of 1617 kg. The REEs emission from IOS is comparable to that from PCu, at 780 kg and 758 kg, respectively. The spatial distribution of REEs emissions from BFI, EAF and IOS is very similar, which is consistent with the distribution of China’s steel industry mainly concentrated in Liaoning, Hebei, Shanxi, Shandong and Jiangsu provinces54. The contribution of other industries to the total REEs emissions is <0.3%. The annual REEs emissions in other industries ranged from 2.50 kg (SPb) to 174.32 kg (SCu), which is 3–4 orders of magnitude lower than that of CK. The main reason for the low REEs emissions in the secondary metal smelting industry is that the output is 2–4 orders of magnitude lower than that of other industries (Supplementary Table 2). Their REEs emission distribution is closely related to the distribution of metal mineral resources. The low REEs concentration in PM from SPb makes it the lowest industrial source of emissions, which can be ignored. The REEs emissions are comparable in quantity to those of secondary metal smelting since the yields of HWI and WI are not overly high and the EFs are extremely low. The construction progress of WI facilities in the southeastern coastal areas is significantly ahead of that in the central and western regions. Among them, Shandong, Jiangsu, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Fujian and Sichuan provinces may be at the forefront of the country in the number of WI facilities and the scale of treatment, so these areas have larger REEs emissions55. The types of waste treated by HWI are more complicated and need to be based on the specific conditions of each region. Yunnan province may deal with more metal smelting waste; Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Shanxi provinces may have a high proportion of coking waste. Various industrial activities such as metal mining, smelting and coking in Shandong province may be more frequent, so there are more industrial wastes.

Industrial activities are closely related to regional economic development. Therefore, we also assessed REEs emissions from a regional economic perspective to help develop regional emission reduction strategies. Figure 5 shows the economic regions distribution (northeast, central, eastern and western regions) of industrial REEs emissions in China and the contribution of each economic region to REEs emissions. The eastern region is the region with the largest REEs emissions (49,666 kg) due to its developed economy and intensive industrial activities. The REEs emissions in the west (44,752 kg) were slightly lower than those in the east, and the REEs emissions in the northeast were one order of magnitude lower (6758 kg). For the industrial sources of CFPP, CK, BFI, EAF, HWI, IOS, SAl and WI, the REEs emissions from the eastern region have a greater contribution (36.05–62.52%). In terms of COP and PCu industrial sources, the central and western regions are the main REEs emission sources. The central region contributes 58.66% to the total REEs emissions of SCu. The REEs emissions from SZn are mainly considered in the western region.

a Economic regional distribution of REEs emissions. b The contribution of each economic region to industrial REEs emissions. BFI blast-furnace pig iron, CFPP coal-fired power plant, CK cement kiln co-processing solid waste, COP coking plant, EAF electric-arc furnace steelmaking, HWI hazardous-waste incineration, IOS iron-ore sintering, PCu primary copper smelting, SAl secondary aluminum smelting, SCu secondary copper smelting, SPb secondary lead smelting, SZn secondary zinc smelting, WI municipal solid-waste incineration.

In summary, it is recommended to give priority attention to PM emission sources with high REEs concentration and large industrial activities, such as CFPP and CK. The primary task of all regions is to strictly control the REEs emissions of these two types of industries, especially in Shandong, Jiangsu and Guangdong provinces in eastern China. In addition, considering the contribution of each province/city to REEs industrial emissions, Shanxi province in the central region, Inner Mongolia and Shanxi province in the western region should also take measures to reduce COP emissions. Compared with EAF and IOS, BFI pollution control is also relatively urgent for the eastern region, especially Hebei province. Yunnan province in the west should also take into account the prevention and control of SZn industrial activities. Based on the emission evaluation in China, it is preliminarily estimated that these 13 global industries unintentionally release 244,708 kg of REEs annually (Supplementary Table 4).

Exposure assessment of REEs from various industrial fine PM

The emission of these 13 industrial activities may lead to an increase of 23.77 ng/m3 of REEs in the atmosphere of China. In some cases, it exceeded the levels measured in air PM10 and PM2.5 near the steel plant30. The industrial sources of CK, CFPP and COP with high REEs emissions may bring 18.27, 2.19 and 2.07 ng/m3 atmospheric increments to REEs, respectively. The amount of atmospheric REEs increased by CFPP is similar to the amount of REEs increased by coal combustion in PM2.5 in Baoding calculated by Shen et al.56. During the 5 years from 2017 to 2021, the REEs released from coal combustion in PM2.5 samples in Baoding decreased from 3.20 to 2.58 ng/m3. These increases in industrial emissions may directly lead to a significant increase in the daily exposure of REEs in PM2.5 in the general population. As shown in Fig. 6a, b, inhalation is the main route of REEs exposure in PM2.5 for children and adults, with an average daily REEs intake of 11.72 and 7.41 ng/(kg·day), respectively. The ingestion and dermal contact pathways accounted for <1% of the total daily exposure of REEs. Regardless of the exposure route, children’s intake of REEs in PM2.5 was higher than that of adults, mainly because of the differences in relevant calculation parameters. CK contributed the most to the inhalation of REEs in PM2.5 [9.01 ng/(kg·day)], followed by CFPP [1.08 ng/(kg·day)] and COP [1.02 ng/(kg·day)] for children. There is currently no official threshold for REEs exposure in PM2.5 related to human health. It has been reported that in rare earth mining areas, the daily intake of 6.00–6.70 mg REEs by adults may cause subclinical damage, and 4.20 mg or less is considered to be a relatively safe range57. Although the total exposure of REEs absorbed by inhalation, ingestion and skin in PM2.5 caused by industrial emissions is lower than this threshold, the trend of industrial activity is still unclear. The human body also ingests REEs from other sources, including food and water. If appropriate emission reduction measures are not taken, the exposure effects caused by changes in the concentration and emissions of REEs in industrial PM may not be underestimated.

a Contributions of REEs in PM from 13 industries to total exposure amount to children via inhalation, ingestion and dermal absorption; b contributions of REEs in PM from 13 industries to total exposure amount to adults via inhalation, ingestion and dermal absorption. BFI blast-furnace pig iron, CFPP coal-fired power plant, CK cement kiln co-processing solid waste, COP coking plant, EAF electric-arc furnace steelmaking, HWI hazardous-waste incineration, IOS iron-ore sintering, PCu Primary copper smelting, SAl secondary aluminum smelting, SCu secondary copper smelting, SPb secondary lead smelting, SZn secondary zinc smelting, WI municipal solid-waste incineration.

Methods

Sample information

In order to ensure the broad representativeness of the samples, PM samples in this study were collected from 114 factories in 13 industries distributed throughout China. The detailed information of the sampling points and PM samples are given in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5, respectively. All PM samples are collected from multiple electrostatic precipitators or bag filters in each plant and are mixed samples taken at different times. Therefore, these samples represent the final products of each factory. This comprehensive field survey can identify the source of REEs and estimate their emissions in a study.

Sample pretreatment and element determination

Based on the US EPA Method 3052 microwave digestion method58, PM samples were pretreated by an improved mixed acid/microwave digestion system to ensure complete digestion (Supplementary Table 6). In step 1, about 0.1 g PM sample (accurate to 0.0001 g) was added to a 100 ml polytetrafluoroethylene digestion tank, and then a mixed acid of concentrated HNO3, HCl and HF (5:2:2, v/v) was added in turn. After sufficient reaction, it was placed in a microwave digestion instrument (ETHOS UP, China) to digest according to the temperature program of step 2. In step 3, after cooling to room temperature, the digestion tube was moved to the electric heating plate, and the acid was expelled at 180 °C. When the liquid became sticky with the size of soybean grains, the obtained solution was further diluted with 10 ml 10% HNO3 and re-digested. In the process, the base concentration of H2SO4 was added to remove the unreacted hydrofluoric acid and fluoride precipitation. If any residue remains, add 2 ml of concentrated HNO3 to continue heating. The final step 4 is to carry out constant volume and filtration. The digestion tube on the electric heating plate is taken off and cooled and transferred to the volumetric flask. The inner wall of the digestion tube is washed several times with 5% HNO3 and constant volume to 50 ml. Subsequently, it was filtered through a 0.45 μm water filter membrane and placed in a refrigerator to be tested. REEs elements were measured by ICP-MS (Shimadzu 2023, Japan).

Quality control

The instrument was calibrated using a REEs multi-element standard solution with a known concentration of the target element. The calibration curves for the elements show linearity within the concentration range (R2 > 0.999), and more details of the calibration curves are shown in Supplementary Table 7. During the digestion of each batch of samples, blank samples, repeated samples and certified reference materials (rock reference material GB07105) were used to control and ensure the quality of the whole experiment. In the digestion of four batches of samples, the recovery rate of the target element is 73.76–100.78% (Supplementary Table 8), and the results are satisfactory. The detection limit of the method is 0.0023–0.0325 μg/g (Supplementary Table 9). Except for Gd and Lu, the relative standard deviation (RSD) of other elements is in the range of 1.13–5.51% (Supplementary Table 9), and the overall accuracy is better.

Emission and exposure risk assessment

The European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme (EMEP)59 and the Emission Factor Method (EF) recommended by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)60 are used to estimate emission inventories for various industrial sectors. Emissions are calculated using a bottom-up approach and the formula is as follows:

where the subscripts \(i\), \(k\) represent specific industrial sectors and end-of-pipe treatment technologies, respectively. \({E}_{i}\) represents the total annual emissions of REEs in industry \(i\) (data from the official website of the National Bureau of Statistics https://www.stats.gov.cn/). In addition to the production data of IOS for 2018, the data of all other industries are from 2020 (Supplementary Table 2). \({A}_{i}\) is the activity intensity of industry i (e.g., the annual output of coke). \({\bar{C}}_{i}\) is the average value of REEs in PM of all factories in industry i. \({{EF}}_{i}\) (Supplementary Table 3) represents the average EF of fine PM in industry \(i\). \({P}_{i,j}\) and \({\eta }_{k}\) (Supplementary Table 3) represent the pollution coefficient of the \(j\) section in industry \(i\) and the removal efficiency of the end treatment technology \(k\), respectively. The data are extracted from China’s Industrial Source Pollution Production and Discharge Coefficient Manual61.

Furthermore, we used the health risk assessment model recommended by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) to assess the potential health risks associated with the increase of these REEs62. The doses of REEs exposed to industrial PM by inhalation (inh), ingestion (ing) and skin absorption (derm) were calculated. The formula is as follows:

where \({{ADD}}_{{inh}}\), \({{ADD}}_{{ing}}\) and \({{ADD}}_{{dem}}\) were the average daily intake doses of REEs through inhalation, ingestion and skin absorption, respectively, ng/(kg·day); \(\it \sum {{{\rm{ADD}}}}\) was the sum of three exposure doses, ng/(kg·day); \(C\) is the increment of REEs concentration in atmospheric PM caused by emissions from 13 industrial activities (inhalation: ng/m3, ingestion: ng/kg, skin absorption: ng/kg); \({InhR}\) is the inhalation rate, m3/day; \({IngR}\) is the intake rate, mg/day; \({EF}\) is exposure frequency, day/years; \({ED}\) is exposure duration, year; \({AT}\) is the average time, = \({ED}\) × 365 days; BW is body weight, kg; \({SA}\) is the exposed skin surface area, cm2; \({SL}\) is skin adhesion factor, mg/cm2 × day; \({ABS}\) is the skin absorption coefficient. The calculation method of REEs concentration increment \(C\) is shown in Supplementary Formula 1. The detailed information of the relevant parameters is given in Supplementary Table 10.

Data availability

The minimum dataset necessary to interpret, verify and extend the work is provided in the Supplementary Information. The concentrations of rare earth elements for Figs. 1–6 are provided in the Supplementary Information. Data in Figs. 4 and 5, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 for emission assessment are collected from international industry associations and official government document, which are introduced in the “Methods” section and provided in References. Data in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 10 for exposure assessment are collected from research results, which are also introduced in the “Methods” section and provided in References.

References

Kurnia, K. A. et al. Deep learning-based automatic duckweed counting using StarDist and its application on measuring growth inhibition potential of rare earth elements as contaminants of emerging concerns. Toxics 11, 680 (2023).

Gwenzi, W. et al. Sources, behaviour, and environmental and human health risks of high-technology rare earth elements as emerging contaminants. Sci. Total Environ. 636, 299–313 (2018).

Patel, K. S. et al. Occurrence of uranium, thorium and rare earth elements in the environment: a review. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1058053 (2023).

Yan, Y. et al. Characteristics and provenances of rare earth elements in the atmospheric particles of a coastal city with large-scale optoelectronic industries. Atmos. Environ. 214, 116836 (2019).

Malhotra, N. et al. An updated review of toxicity effect of the rare earth elements (REEs) on aquatic organisms. Animals 10, 1663 (2020).

Tepe, N., Romero, M. & Bau, M. High-technology metals as emerging contaminants: strong increase of anthropogenic gadolinium levels in tap water of Berlin, Germany, from 2009 to 2012. Appl. Geochem. 45, 191–197 (2014).

Wang, L. & Liang, T. Geochemical fractions of rare earth elements in soil around a mine tailing in Baotou, China. Sci. Rep. 5, 12483 (2015).

Pagano, G., Guida, M., Tommasi, F. & Oral, R. Health effects and toxicity mechanisms of rare earth elements—knowledge gaps and research prospects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 115, 40–48 (2015).

Xia, Q. et al. The neural toxicity of lanthanides: an update and interpretations. Sci. China Press. 42, 1308–1314 (2012).

Sabbioni, E. et al. Long-term occupational risk of rare-earth pneumoconiosis: a case report as investigated by neutron activation analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 26, 19–32 (1982).

Tong, Y. et al. Seasonal variation of rare earth element concentrations in PM10 and their cytotoxicity in a typical rare earth mining city. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 12, 129–140 (2017).

Gao, J. et al. Determining the cytotoxicity of rare earth element nanoparticles in macrophages and the involvement of membrane damage. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13938–13948 (2017).

Huang, Y. et al. Quantification of global primary emissions of PM2.5, PM10, and TSP from combustion and industrial process sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 13834–13843 (2014).

Franus, W., Wiatros-Motyka, M. M. & Wdowin, M. Coal fly ash as a resource for rare earth elements. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 9464–9474 (2015).

Seredin, V. V. & Dai, S. Coal deposits as potential alternative sources for lanthanides and yttrium. Int. J. Coal Geol. 94, 67–93 (2012).

Liu, C. et al. Fast screening of coal fly ash with potential for rare earth element recovery by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 16716–16722 (2021).

Pan, J. et al. Recovery of rare earth elements from coal fly ash by integrated physical separation and acid leaching. Chemosphere 248, 126112 (2020).

Pan, J., Hassas, B. V., Rezaee, M., Zhou, C. & Pisupati, S. V. Recovery of rare earth elements from coal fly ash through sequential chemical roasting, water leaching, and acid leaching processes. J. Clean. Prod. 284, 124725 (2021).

Huang, Z., Fan, M. & Tian, H. Rare earth elements of fly ash from Wyoming’s Powder River Basin coal. J. Rare Earths 38, 219–226 (2020).

Sahoo, P. K., Kim, K., Powell, M. A. & Equeenuddin, S. M. Recovery of metals and other beneficial products from coal fly ash: a sustainable approach for fly ash management. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 3, 267–283 (2016).

Gerardo, S., Matthews, K., Warner, J. & Song, W. Role of nanoscale crystallinity on the recovery of rare earth elements (REEs) from coal fly ash. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 10, 943–948 (2023).

Smith, R. C., Taggart, R. K., Hower, J. C., Wiesner, M. R. & Hsu-Kim, H. Selective recovery of rare earth elements from coal fly ash leachates using liquid membrane processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 4490–4499 (2019).

Blissett, R. S., Smalley, N. & Rowson, N. A. An investigation into six coal fly ashes from the United Kingdom and Poland to evaluate rare earth element content. Fuel 119, 236–239 (2014).

Strzałkowska, E. Rare earth elements and other critical elements in the magnetic fraction of fly ash from several Polish power plants. Int. J. Coal Geol. 258, 104015 (2022).

Adamczyk, Z., Komorek, J. & Lewandowska, M. The high temperature ashes (HTA) from bituminous coal combustion as a potential resource of rare earth elements. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. Miner. Resour. Manag. 34, 135–150 (2018).

Adamczyk, Z., Komorek, J., Kokowska-Pawłowska, M. & Nowak, J. Distribution of rare-earth elements in ashes produced in the coal combustion process from power boilers. Energies 16, 2696 (2023).

Saikia, B. K., Hower, J. C., Islam, N., Sharma, A. & Das, P. Geochemistry and petrology of coal and coal fly ash from a thermal power plant in India. Fuel 291, 120122 (2021).

Mondal, S. et al. Recovery of rare earth elements from coal fly ash using TEHDGA impregnated resin. Hydrometallurgy 185, 93–101 (2019).

Kumari, A., Panda, R., Jha, M. K., Kumar, J. R. & Lee, J. Y. Process development to recover rare earth metals from monazite mineral: a review. Miner. Eng. 79, 102–115 (2015).

Dai, Q. et al. The fractionation and geochemical characteristics of rare earth elements measured in ambient size-resolved PM in an integrated iron and steelmaking industry zone. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 17191–17199 (2016).

Yang, Q. et al. Atmospheric emissions of particulate matter-bound heavy metals from industrial sources. Sci. Total Environ. 947, 174467 (2024).

Ketris, M. P. & Yudovich, Y. E. Estimations of Clarkes for Carbonaceous biolithes: world averages for trace element contents in black shales and coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 78, 135–148 (2009).

Kolker, A. et al. Distribution of rare earth elements in coal combustion fly ash, determined by SHRIMP-RG ion microprobe. Int. J. Coal Geol. 184, 1–10 (2017).

Fu, B. et al. A review of rare earth elements and yttrium in coal ash: content, modes of occurrences, combustion behavior, and extraction methods. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 88, 100954 (2022).

Okeme, I. C. et al. An advanced analytical assessment of rare earth element concentration, distribution, speciation, crystallography and solid-state chemistry in fly ash. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 177, 105950 (2021).

Besari, D. A. A., Anggara, F., Rosita, W. & Petrus, H. T. B. M. Characterization and mode of occurrence of rare earth elements and yttrium in fly and bottom ash from coal-fired power plants in Java, Indonesia. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 9, 20 (2022).

Wang, S., Yu, R., Hu, G., Hu, Q. & Zheng, Q. Distribution and source of rare earth elements in PM2.5 in Xiamen, China. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 36, 3217–3222 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Geochemical characteristics and source apportionment of rare earth elements in the dustfall of Quanzhou city. Environ. Sci. 12, 0250–3301 (2016).

Taggart, R. K., Hower, J. C., Dwyer, G. S. & Hsu-Kim, H. Trends in the rare earth element content of U.S.-based coal combustion fly ashes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 5919–5926 (2016).

Zhao, L., Zhang, F. S. & Zhang, J. Chemical properties of rare earth elements in typical medical waste incinerator ashes in China. J. Hazard. Mater. 158, 465–470 (2008).

Rao, A. K., Md, S., RamaDevi, G., Thakurta, S. G. & Sreenivas, T. On the characterization and leaching of rare earths from a coal fly ash of Indian origin. Sep. Sci. Technol. 56, 541–557 (2021).

Lu, D. et al. Natural silicon isotopic signatures reveal the sources of airborne fine particulate matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 1088–1095 (2018).

Olmez, I. & Gordon, G. E. Rare earths: atmospheric signatures for oil-fired power plants and refineries. Science 229, 966–968 (1985).

Zhao, Y., Yu, R., Hu, G., Lin, X. & Liu, X. Characteristics and environmental significance of rare earth elements in PM2.5 of Nanchang, China. J. Rare Earths 35, 98–106 (2017).

Dai, S., Graham, I. T. & Ward, C. R. A review of anomalous rare earth elements and yttrium in coal. Int. J. Coal Geol. 159, 82–95 (2016).

Perämäki, S. E., Tiihonen, A. J. & Väisänen, A. O. Occurrence and recovery potential of rare earth elements in Finnish peat and biomass combustion fly ash. J. Geochem. Explor. 201, 71–78 (2019).

Funari, V., Bokhari, S. N. H., Vigliotti, L., Meisel, T. & Braga, R. The rare earth elements in municipal solid waste incinerators ash and promising tools for their prospecting. J. Hazard. Mater. 301, 471–479 (2016).

Wang, C. X., Zhu, W., Peng, A. & Guichreit, R. Comparative studies on the concentration of rare earth elements and heavy metals in the atmospheric particulate matter in Beijing, China, and in Delft, the Netherlands. Environ. Int. 26, 309–313 (2001).

Suzuki, Y., Suzuki, T. & Furuta, N. Determination of rare earth elements (REEs) in airborne particulate matter (APM) collected in Tokyo, Japan, and a positive anomaly of europium and terbium. Anal. Sci. 26, 929–935 (2010).

Hoàng-Hòa, T. B. et al. Pb, Sr and Nd isotopic composition and trace element characteristics of coarse airborne particles collected with passive samplers. C. R. Geosci. 347, 267–276 (2015).

Lahd Geagea, M., Stille, P., Gauthier-Lafaye, F. & Millet, M. Tracing of industrial aerosol sources in an urban environment using Pb, Sr, and Nd isotopes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 692–698 (2008).

International Energy Agency. Coal 2019-Analysis and Forecasts to 2024 https://www.iea.org/reports/coal-2019 (2019).

Wang, T. et al. Reflection on China’s coal resource guarantee capacity and exploration work under the background of “double carbon”. Coal Sci. Technol. 51, 1–8 (2023).

Gao, W. et al. The evolution of China’s iron and steel industry layout and its influence on the spatial and temporal distribution of air pollutants. Master’s thesis, Northeastern University (2020).

Yang, J. et al. The environmental society of domestic waste incineration facilities in county-level areas of China risk analysis and coping strategies research-based on the analysis of facility load rate and network public opinion in 31 provinces. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 6, 1674–6252 (2023).

Shen, Y. et al. Insight study of rare earth elements in PM2.5 during five years in a Chinese inland city: composition variations, sources, and exposure assessment. J. Environ. Sci. 138, 439–449 (2024).

Zhu, W. et al. Investigation on intake allowance of rare earth—a study on bio-effect of rare earth in South Jiangxi. Chin. Environ. Sci. 1, 63–66 (1997).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Method 3052: microwave assisted acid digestion of siliceous and organically based matrices. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/3052 (1996).

European Environment Agency. EMEP/EEA air pollutant emission inventory guidebook 2023: technical guidance to prepare national emission inventories. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/emep-eea-guidebook-2023 (2023).

United Nations Environment Programme. Toolkit for identification and quantification of releases of dioxins, furans and other unintentional POPs under Article 5 of the Stockholm Convention. https://toolkit.pops.int/ (2013).

Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Handbook of emission sources inventory survey, pollution discharge calculation methods, and coefficients. https://www.mee.gov.cn (2021).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Risk assessment guidance for superfund, Volume I: human health evaluation manual 637 (Part A). https://www.epa.gov/risk/ risk-assessment-guidance-superfund-rags-part (1989).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant numbers XDB0750400, XDB0750100, XDB0750000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 21936007, 22376204, 22076201), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP) (grant number 2019 QZKK0605), Chinese Academy of Sciences Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (grant number YSBR-086).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. conducted the laboratory analysis of samples, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. Q.Y., C.Z. and C.C. collected and organized the relevant sample information, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript; G.L. designed the research, conducted data analysis and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ahsan Habib, Jianlin Wu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yun, J., Yang, Q., Zhao, C. et al. Atmospheric emissions of fine particle matter bound rare earth elements from industry. Nat Commun 15, 9338 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53684-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53684-6

This article is cited by

-

Municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash in concrete : A systematic review and meta-analysis

Scientific Reports (2025)