Abstract

Achieving achromaticity across the visible light spectrum is crucial for metalenses in imaging systems. Single-layer metalenses struggle with weak focusing power or small aperture sizes due to inadequate group delay control. Multilayer metalenses offer some improvement but come with increased design and fabrication complexity. Here, we demonstrate a strategy using meta-atoms with material layers engineered for matching dispersion, allowing large and fine adjustments of group delay. Our design substantially broadens the group delay range, allowing us to experimentally demonstrate several polarization-independent metalenses operating across the entire visible spectrum (400-700 nm). We design, fabricate, and characterize achromatic metalenses with aperture diameters of 16 μm, 66 μm, 200 μm, and 400 μm, and numerical apertures of 0.27, 0.11, 0.04, and 0.02, respectively. Among them, the 400-μm diameter, 0.02-numerical-aperture metalens is used to demonstrate full-color imaging capabilities. Our results exhibit diffraction-limited performance, high efficiency, and accurate full-color image reproduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metalenses, which are flat lenses that manipulate light using sub-wavelength artificial structures known as meta-atoms, have gained considerable attention since their emergence1,2,3. Their capability to bend light like conventional lenses but within an extraordinarily thin and flat form factor promises a major paradigm shift in current optical industries4,5,6,7. Despite their potential, metalenses face the issue of chromatic aberration due to their reliance on the resonant transmission of light. To overcome this challenge, it is necessary to ensure that light passing through all locations of the lens arrives at the focal point simultaneously, requiring the metalens to compensate for differences in group delays (GDs) between the lens input surface and focal point8,9,10,11,12.

Efforts to achieve GD compensation in metalenses have exploited the resonant dispersive phase compensation of meta-atoms8,13,14,15 combined with the geometrical phase for circularly polarized light16,17. However, the amount of GD compensation they could provide is minimal due to the ultrathin thickness of meta-atoms. More recent attempts to improve GD compensation in metalenses through more complex meta-atom designs, such as those with ultra-high aspect ratios18,19, multiple scattering elements20, and free-form shapes21 have had limited success. These designs require challenging fabrication processes. In addition, it can be difficult to find meta-atom designs that effectively balance the requirements for phase delay and GD. Ultimately, the key to improving GD compensation may lie in optimizing the entire, continuous topology of the metalens22,23,24. Although this approach has the potential to improve GD compensation significantly, it is computationally challenging, limiting the size of the metalenses that can be designed, and may result in exotic nanofabrication requirements.

Therefore, multilayer structures for creating achromatic metalenses have been explored, but current multilayer designs use stacked layers of independent metalenses25,26, where each layer is responsible for focusing at one wavelength. This limits the metalens working on only a few discrete wavelengths (usually two or three) achromatically27. Moreover, the stacking method introduces loss due to the additional interfaces as well as crosstalk among the layers. They also require a one-to-one correspondence between the meta-atoms in two neighboring layers, which poses a challenge to pattern alignment during the fabrication of such metalenses28,29.

On the other hand, given the limited GD range producible by single layer meta-atoms, some works also shift their focus from pure metasurface lens to a hybrid configuration, where metasurfaces are used along with traditional refractive optical components and serve as correctors. This approach greatly relieves the range of GD that needs to be provided by the meta-atoms with the help of the refractive component, but also has its own drawbacks: first, it has been shown that for an ideal achromatic lens, the required phase at each point of the lens should be linearly changing with the frequency of the incident light, i.e., the phase has a linear dispersion. As a result, meta-atoms with such linear dispersion can be used to construct achromatic metalenses. and thanks to the well-known truncated waveguide theory, this linear dispersion relation holds for most dielectric, non-resonant meta-atoms such as nanopillars. However, with the addition of a refractive element, it is shown that the required phase now for the meta-correctors varies nonlinearly with frequency, which implies that more complicated, resonant-based meta-atoms must be used to compensate such nonlinear relation, thus bringing additional complexity to the design; on the other hand, the design specifications of such hybrid devices are still subject to the range of GD that can be provided by the single-layer meta-atoms, which still poses a limit on the scalability of this method.

Moreover, the recent development of multilevel diffraction lenses (MDLs)30,31,32 has introduced lenses made of concentric dielectric layers with varying heights determined by the desired phase profiles. Similar to metalenses, these MDLs could realize synchronized focusing of light from different areas of the aperture and have demonstrated achromatic focusing and imaging through novel design and optimization strategies. However, the wavelength-scale widths of the concentric dielectric rings pose a fundamental limit to their performance (e.g., Strehl ratio) due to undesired diffraction.

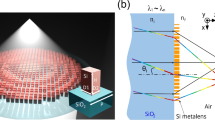

To address these challenges, we present a design of broadband dispersion compensated metalenses that achieve continuous achromatic focusing and imaging across the entire visible light spectrum (400 nm–700 nm). The metalenses are composed of a combination of elements, including a subwavelength-sized nanoantenna made of high-refractive-index silicon nitride (SiN) on top and a pair of layers consisting of low-dispersion SiN and SU8 at the bottom. The low-dispersion SiN is specially engineered to match the dispersion of SU8. The bottom dispersion-matched layers provide large, coarse, and discretized values of GD compensation (Fig. 1A, bottom), while the top nanoantenna layer provides fine control over the GD via the antennas’ resonant modes. In this way, the GD compensation produced by the top nanoantennas can be “reused” with the large, coarse GD offset provided by the bottom dispersion-matched layers. The top nanoantennas are also responsible for imposing phase delay to transform the incident wave into a focusing wavefront (Fig. 1A, top). Utilizing this scheme of dispersion-matched layers, the compound meta-atoms compensate GD profiles accurately across the entire aperture and synchronize all light at the focal point (Fig. 1B). Our method relieves the top nanoantennas from most of the GD compensation tasks, thus allowing for simpler, more fabrication-friendly nanoantenna shapes without deteriorating the performance. Moreover, we designed an algorithm to prevent the dispersion-matched layers from experiencing rapid oscillations in thickness along the radial direction, simplifying fabrication. Compared to current multilayer schemes, our metalenses achieve continuous achromatic focusing across a broad spectral range, with reduced fabrication and alignment efforts, thanks to the large feature sizes of the SiN-SU8 dispersion-matched layers.

A Schematic representation of the top nanoantennas incorporated with a pair of dispersion-matched layers on the bottom, providing fine and coarse two levels of group delay compensation. The black lines illustrate the spatial distributions of the group delay. B Artistic illustration of broadband white light being focused by an achromatic metalens.

In this work, we design, fabricate, and characterize several achromatic, polarization-independent metalenses with aperture sizes of 16, 66, 200, and 400 μm, and numerical apertures (NAs) of 0.27, 0.11, 0.04, and 0.02, respectively to validate our approach. We experimentally observe diffraction-limited focusing and imaging performance with Strehl ratios over 90% across the entire visible spectrum. Our metalenses provide a focal length deviation across the visible band as small as 1.61% of the designed focal length. The best-focusing efficiency is measured to be 88%. We believe our design approach provides a viable path toward realizing fast, large aperture and high-performance achromatic metalenses through the extension of GD range beyond what was possible previously, which will facilitate their application in practical optical devices.

Results

Design principles of the achromatic metalenses with dispersion-matched layers

In our broadband dispersion-compensated metalens, the top nanoantenna layer and bottom dispersion-matched pairs were designed as a whole instead of separately. The coupling between the two layers is automatically taken care of as the constituent meta-atoms include both components – the high-index SiN top nanoantennas and the bottom dispersion-matched SiN-SU8 pairs (Fig. 2B, inset). We used six types of shapes for the nanoantennas (Fig. 2A, inset), which all possess C4 symmetry, rendering the design polarization independent. The transmission phase and GD of each meta-atom were determined by combining full-wave simulations with the transfer-matrix (T-matrix) method, as detailed in the Methods section. The transmission phase can be sampled at an arbitrary wavelength (700 nm in our case) in the band of interest and \(\frac{\partial \varphi }{\partial \omega }\) is calculated as the amount of group delay. To calculate the group delay, we approximate the phase spectrum of all meta-atoms with least-square linear regression across the working bandwidth of 321.21 THz, from 400 nm to 700 nm. Figure 2A shows the phase and GD from the top nanoantennas with a fixed bottom SiN layer thickness, with each dot representing an individual nanoantenna design. Although a phase coverage of 2π is achieved, the GD coverage remains significantly limited, creating a substantial bottleneck for achromatic metalens designs with large aperture sizes and high numerical apertures (NA). This limitation is evident in the narrow span of the point cluster along the y-axis in the phase-GD diagram (Fig. 2A). It can be attributed to both the moderate height (600 nm) of the SiN nanoantennas and the relatively low refractive index of the nanoantenna material compared to their near-infrared counterparts (e.g., silicon)11.

A Phase and group delay is provided by the nanoantennas alone (with a fixed bottom SiN layer thickness). \(\Delta {\tau }_{g,{\mathrm{max}}}^{\left(t\right)}\) indicates the maximum GD range. Inset: the six types of nanoantennas used in the design. B The phase-GD diagram with extended achievable group delay range by the meta-atoms with different bottom SiN layer thicknesses (clusters of colored dots). The required phases and group delay values of ideal achromatic metalenses are indicated by black dots. Note: points with the same color do NOT imply the same thickness of the SiN layers. C Top: the dispersion of the refractive indices of the high-index SiN (nanoantennas), SU8, and low-dispersion SiN. The dispersion of low-dispersion SiN matches that of SU8, thanks to engineering in synthesis condition and material composition. Bottom: the index difference between SU8 and dispersion-engineered SiN across the visible light spectrum (400 nm–700 nm). The maximum dispersion mismatch is 0.0015. D The surface formed by the required phase and local average group delay (LAGD) at different frequencies of the achromatic metalens to be designed, along with the meta-atom phase-LAGD point clusters at various frequencies. The notation of dot colors is the same as in (B). The addition of \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\) helps to modify the meta-atom phase spectra to achieve better coverage of the design requirement, as indicated with the arrows. E The effect of the two-step optimization process used to simplify the bottom SiN layer thickness profile. The red domains indicate regions with fast oscillating layer thicknesses, while the green domains show the layer thicknesses in these regions after the two-step process. F Comparison between the theoretical phase profile (lines) and the realized phase profile (dots) of the designed achromatic metalens across the seven equally spaced wavelengths.

We addressed this issue by placing two dispersion-matched materials, deposition-engineered SiN, and SU8, beneath the nanoantenna layer. By adjusting the thickness difference between the two materials, we can effectively shift the point cluster in the phase-GD diagram in both the x(phase)- and y(GD)-directions. Since GD is linearly dependent on phase for an ideal achromatic lens, with a slope of 1/ω, we ideally require the point clusters to shift linearly with the same slope when varying the thickness of the bottom SiN.

From our theoretical derivations (see Supplementary Note S1), we observed that the additional group delay, denoted by \({\tau }_{g}^{\left(b\right)}\), provided by the bottom SiN-SU8 pairs, can remain invariant across the working band if there is a constant refractive index difference, \(\Delta n={n}_{{{\rm{SiN}}}}^{\left(b\right)}\left(\lambda \right)-{n}_{{{\rm{SU}}}8}\left(\lambda \right)\), between the bottom SiN and SU8\(.\) The approximate expression for \({\tau }_{g}^{\left(b\right)}\) is given by

where c is the speed of light in the vacuum, \({h}_{0}\) is a constant indicating the total thickness of the SiN-SU8 dispersion-matching pair, \({h}_{{{\rm{SiN}}}}\) is the bottom SiN layer thickness, and \({n}_{{{\rm{SiN}}}}^{\left(b\right)}\) and \({n}_{{{\rm{SU}}}8}\) are the refractive indices of bottom SiN and SU8, respectively. Therefore, by varying the height of the SiN layer, we can modulate the additional group delay, which is significantly larger than that can be provided by the top nanoantenna layer, albeit with larger granularity. Setting a thickness variation interval for the bottom SiN layer to no greater than \({\Delta h}_{{{\rm{SiN}}},{\mathrm{max}}}\approx \frac{c\Delta {\tau }_{g,{\mathrm{max}}}^{\left(t\right)}}{{n}_{{{\rm{SiN}}}}^{\left(b\right)}-{n}_{{{\rm{SU}}}8}}\) allows us to expand the group delay coverage by the point cloud in the phase-GD diagram multiple times without eliminating their overlapping regions (Fig. 2B). Here, \(\Delta {\tau }_{g,{\mathrm{max}}}^{\left(t\right)}\) is the maximum GD range provided by the top nanoantennas. With our design scheme, the extended GD range can be written as:

where \({N}_{b}\) is the number of different thicknesses of the bottom SiN layer (\({N}_{b}=0\) means a flat surface) and \(\alpha\) is a coefficient between 0 and 1. \(\alpha\) is introduced to account for the overlapping between phase-GD point clusters corresponding to each SiN thickness. It is defined as the ratio between the actual thickness interval of the SiN layers and the maximum interval allowed: \(\alpha={\Delta h}_{{{\rm{SiN}}}}/{\Delta h}_{{{\rm{SiN}}},{\mathrm{max}}}\). An \(\alpha=1\) indicates that neighboring point clusters are connected with each other with no overlap, while \(\alpha=0\) indicates complete overlap. From this relation, it is evident that our metalens design scheme scales up the GD producible by the meta-atoms by \((1+\alpha {N}_{b})\) times, without introducing any new nanoantenna designs.

To fulfill the requirement described above, we chose SiN and engineered its dispersion to maintain a constant refractive index difference with the spacer material, SU8. SiN has the ability to be engineered through synthesis conditions and material composition33,34,35. We synthesized SiN films under different conditions and compositions, characterizing their indices through ellipsometry measurements. We demonstrated a wide range of tunable indices and highly flexible dispersion curves for our SiN films (see Supplementary Note S2 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Through this process, we optimized the dispersion of the SiN across the targeted spectral band, ensuring a nearly constant refractive index difference with SU8 (Fig. 2C), with the maximum dispersion mismatch as low as 0.0015 across the entire visible spectrum. As a result, the GD range can be scaled up significantly (Fig. 2B) compared to the contribution from the nanoantennas alone.

In general, the required phase profile of a metalens at any arbitrary radial position r can be written as

where f is the focal length and ω is the angular frequency. The required GD can be expressed as \({\tau }_{g}\left(r\right)=\frac{\partial \varphi \left(r,\omega \right)}{\partial \omega }=\frac{1}{{\omega }_{0}}\left[\varphi \left(r,{\omega }_{0}\right)-{\varphi }_{0}\right]\), where \(\varphi \left(r,{\omega }_{0}\right)\) is the required phase shift at an arbitrary reference angular frequency \({\omega }_{0}\), and \({\varphi }_{0}\) is the phase shift at the reference frequency. This linear relationship has been utilized in designing achromatic metalenses in earlier studies8,11,18,20 and is illustrated by the black dotted line in Fig. 2B, referred to as the “requirement line” thereafter.

By analyzing the overlap between the “requirement line” and the point clusters from the meta-atom library in the phase-GD plot (Fig. 2B), we can assess the design limitations and capabilities of the existing meta-atom library for constructing achromatic metalenses. Substantial overlap between the “requirement line” and the point clusters, as observed in Fig. 2B, indicates the potential to achieve broad-range group delay compensation, which is crucial in the design of broadband achromatic metalenses.

Although the straightforward presentation of the phase-GD plot may tempt many to design a metalens directly from it, the inevitable existence of resonances in the meta-atoms causes their phase response to deviate from linear phase dispersion. This results in a frequency-dependent GD, meaning that representing each meta-atom design with a single GD value is not entirely accurate.

To address the issue of frequency dependence of GD, we investigated the average of GD across a specific frequency range, Δω, at each frequency of interest, ω, within the working band. This led us to define a local average group delay (LAGD) for the meta-atoms:

This quantity provides additional flexibility in designing metalenses compared to the traditional definition of GD. It accounts for the nonlinearity in the phase dispersion of the meta-atoms. In the case of a meta-atom that exhibits exactly linear phase dispersion, the LAGD simplifies to the standard GD.

To reconcile the meta-atom's frequency-dependent LAGD with the required constant GD from Eq.3, we introduce a frequency-dependent phase offset \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\) to the phase spectra of all meta-atoms. Since \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\) acts as a constant phase shift on all meta-atoms at each frequency, it does not alter the behavior of the metalens. This adjustment allows us to compensate for the meta-atoms LAGDs by appropriately choosing \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\) so that

In Fig. 2D, we illustrate the effect of \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\) by displaying the phase-GD relationships at various frequencies (cut planes with red, green, and blue edges), as well as the phase-LAGD pairs of the meta-atoms at those frequencies. Without the addition of \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\), the phase-LAGD point clusters (shown in light gray) of meta-atoms do not have a good overlap with the requirement lines (depicted as black dotted lines) at all frequencies due to the nonlinearity in meta-atom phase dispersions. In contrast, after incorporating \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\), it alters both the phases and LAGDs of the meta-atoms, shifting the point clusters (shown in colors) to achieve a much better overlap with the requirement lines at all frequencies. In practice, we used a global optimization process to find the optimal \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\).

So far, the metalens design process described above only considers the design that provides the best matching phase and GD, regardless of the monotonicity of the bottom-layer layer thicknesses when the meta-atoms are assembled. As a result, there is a possibility that bottom SiN thickness at neighboring sites will change in an oscillatory manner to obtain the absolute optimal performance in optimization, which could lead to unnecessary fabrication challenges. This issue can be avoided if we include the constraint of a smooth bottom SiN thickness profile during the optimization. However, such a multi-objective optimization would take much more effort to find the optimal solution. Therefore, we developed a simple two-step strategy to guarantee a monotonic layer thickness variation: First, a global optimization without layer thickness constraint is performed to find the globally optimal layout; Second, a local optimization is used to fine-tune the layer thicknesses, using the previous optimal solution as its initial condition. Figure 2E illustrates the effect on layer thicknesses from this two-step optimization process. This strategy allows us to quickly reach the proximity of the actual optimal solution and enforce the layer thickness monotonicity constraint without significant performance deterioration and extended optimization time. Figure 2F shows the required and realized phase profiles of our finalized metalens design at seven sampling wavelengths, with minimal phase deviations.

Achromatic metalens sample fabrication

Utilizing our design strategy, we created a set of achromatic metalenses with aperture sizes of 16, 66, 200, and 400 μm, and NAs of 0.27, 0.11, 0.04, and 0.02, respectively. In the last two designs, six bottom SiN layer thicknesses, i.e., six SiN stairs, were used instead of the four used in the first two designs, all with a 1.2 μm height interval. The bottom layers of the designed metalenses were fabricated using photolithography processes, and their top layers were fabricated using electron-beam lithography processes. The SEM images of the bottom SiN stairs (Fig. 3B) and the top SiN nanoantennas (Fig. 3C) show well-resolved patterns and great sidewall verticalness. A detailed description of the nanofabrication process can be found in the Methods and Supplementary Note S3.

A The optical setup for the characterizations. B A tilted-beam scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of the bottom SiN stairs. Scale bar: 30 μm. (Inset) Microscope image of the SiN stairs. Scale bar: 50 μm. C A top-view SEM image of the achromatic metalens. Scale bar: 800 nm. (Inset) A tilted-beam SEM of the nanoantennas, revealing highly vertical sidewalls. Scale bar: 600 nm. D Transverse (bottom panels) and longitudinal (top panels) cross-sections of the light intensity distribution in the proximity of the focus at seven equally spaced wavelengths from 400 nm to 700 nm. The red dashed line indicates the designed focus position. E Measured focal length versus wavelength change. F Measured full-width-at-half-maximum of the focal spot versus wavelengths, in comparison with the theoretically calculated diffraction-limited value. G Measured Strehl ratio of the focus spots versus wavelengths. A reference value of 0.8 (considered diffraction-limited) is shown by the dashed red line.

Focusing performance characterization of the achromatic metalenses

We characterized the focusing performance of our fabricated metalenses using a typical microscope-type imaging system (Fig. 3A). The light intensity distribution after the metalens was captured by a 10 × objective and a 200-mm-focal-length tube lens. Figure 3D shows the measured transmitted light intensity distribution in both the longitudinal cross-section and the focal plane at seven wavelengths evenly distributed from 400 nm to 700 nm, for the 400-μm-aperture metalens. We observed a focal spot stable at 12.5 mm, showing little variations of the focal lengths across the entire visible light spectrum, which matches well with our design (Fig. 3D). Similarly, we also characterized the focal length for the other three fabricated metalenses. The measured focal lengths for all four metalenses show negligible variation across the entire visible light spectrum (Fig. 3E).

The resolution of an ideal imaging system is bounded by a fundamental limit known as the diffraction limit. We measured the full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of the focal spot at each wavelength for all metalenses and compared the results to the diffraction limit. As shown in Fig. 3F, the measured spot sizes are very close to the diffraction limit, suggesting diffraction-limited performance. To quantitatively verify that, we also characterized the Strehl ratio of our lenses at different wavelengths, as shown in Fig. 3G. The Strehl ratio is a quantity that characterizes the quality of the point spread function (PSF) formed by an imaging system. Any system that has a value of 0.8 or higher is usually considered to have diffraction-limited performance36. Our metalenses achieved a Strehl ratio of around 0.85 or higher at most of the wavelengths and exceeded 0.8 at all wavelengths.

Moreover, the absolute efficiencies of the metalenses are also measured at all wavelengths. The details and the results of the efficiency measurement can be found in Supplementary Note S4 and Supplementary Fig. S5. For smaller aperture lenses with 4 or 6 stairs, the measured efficiency is relatively low (average 15–20%), but for the larger aperture lenses, an average efficiency of ~ 50% is observed, with the highest efficiency value measured to be 88%, for the lens with NA = 0.11 at 550 nm. We attribute the reduced efficiency for smaller aperture metalenses to their increased susceptibility to fabrication and alignment errors, which we validated through full-wave simulation of exemplary metalenses with center-to-center offsets between the top nanoantennas and the bottom stairs of dispersion-matched SiN (see Supplementary Note S8 and Supplementary Fig. S11). We believe these defects can be further mitigated by adopting multiple alignment markers and refining the writing and etching processes.

Full-color imaging tests of the achromatic metalenses

We tested our metalenses with near-ideal PSFs to validate the imaging capabilities in various scenarios. The results for the 400 μm aperture metalens are presented in Figure 4. We started with a standard 1951 USAF resolution test target as the object, which was illuminated by a collimated broadband white light source. The metalens was used as an objective lens, coupled with a 30 mm achromatic doublet lens (serving as the tube lens) to form a 2f-2f imaging system, and a color CCD was used to capture the image (See the detailed testing process and setup in the Methods and Supplementary Fig. S4). Since our substrate contains an array of multiple fabricated metalenses, we used a 0.5 mm diameter pinhole to select one metalens to test and block all others. The finest line group that our metalens can resolve under white light illumination is Group 5 Element 6 (G5E6), which corresponds to a resolution of 57 line pairs per mm (lp/mm) and a line width of 8.77 μm (Fig. 4A). Figure 4 B–D show the separated RGB channels of the raw image captured by the color CCD, exhibiting a well-balanced spectral response. Upon inspection of the individual color channel images, we find that the G5E6 lines can be resolved in the blue and green channels but not in the red channel (see Supplementary Fig. S12). This aligns with our calculations of the diffraction-limited resolution. In addition, modulation transfer function (MTF) curves of the 400 μm aperture metalens at all wavelengths tested are also calculated (see Supplementary Note S5) from the image of the point spread function (PSF) to characterize the imaging capability of the metalens. Shown in Supplementary Fig. S6, the MTF curves (along both tangential and sagittal directions) demonstrate good alignment with the diffraction-limited MTF curves, and share the same cutoff spatial frequency. This result further reinforces the fact that our metalenses perform in a nearly diffraction-limited manner.

A Image of the USAF 1951 resolution test chart, illuminated by a white light source and imaged by the metalens, captured with a color CCD camera. Images from the red (B), green (C), and blue (D) channel images are extracted and shown. E–J Images of different colorful pictures as target objects. Captured images: (E), (G), and (I); Original pictures: (F), (H), and (J). All scale bars: 200 μm. Image source: freesvg.org under the CC 1.0 universal license.

Finally, we used our metalenses to image full-color images. Three different color images (Fig. 4F, H, and J) were used as objects, which were displayed on a Full-HD liquid crystal display (LCD) and transferred to the object plane of the metalens with an inverse microscope system with a 15x size reduction. The obtained images are shown in Fig. 4E, G, and I, respectively. We observe that the colors and details of the target images are well-resolved by our metalenses, and the colors were preserved with high fidelity, indicating achromatic performance across the visible light spectrum. The imperfect edges of the obtained images were caused by the pinhole we used to select the metalens for the test. As we cannot eliminate the distance between the pinhole and the metalens, it leads to a limited maximum chief ray angle (CRA) on the object side, causing vignetting of the images.

Discussion

In this paper, we report an approach for designing broadband achromatic metalenses. By using meta-atoms that consist of high-refractive-index nanoantennas and a pair of dispersion-matched layers, we can achieve a group delay compensation range significantly larger than that possible with nanoantennas alone. To demonstrate our approach, we designed, fabricated, and tested several achromatic, polarization-independent metalenses with aperture sizes of 16, 66, 200, and 400 μm, and NAs of 0.27, 0.11, 0.04, and 0.02, respectively, operating across the entire visible spectrum. Experimental characterization results show stable focal lengths across the entire visible light spectrum (400 nm–700 nm), with mostly > 0.9 Strehl ratios and near diffraction-limited PSFs.

Our broadband achromatic metalenses make use of the bottom dispersion-matched layers to expand the range of group delay compensation beyond what was previously possible due to material constraints and nanofabrication limitations. This method can be easily incorporated into existing meta-atom designs and is applicable across all frequency ranges and material platforms. The larger feature size of the stairs, compared to the nanoantennas, enables their fabrication using photolithography processes, which are CMOS compatible and mass production friendly. Moreover, the additional GD extension provided by the stairs is only limited by their height range and material index, suggesting the potential for even greater performance improvements34.

Thanks to SiN being a proven platform for flexible dispersion tuning and large index changes with varying compositions, we were able to control the dispersion of the bottom SiN layer matching with that of the SU8 spacer by a constant index difference to maximize GD extension. During our attempts, we optimized the SiN synthesis process and achieved deposition of SiN with index difference fluctuation no larger than 0.0015 across the entire visible light spectrum. Leveraging such dispersion matching, we created an exemplary compound meta-atom library with 25 stairs, which allows us to expand the attainable GD range to near 40 fs, an order of magnitude larger than previously reported meta-atom library GD ranges (see Fig. 2B and Supplementary Note S6). Due to the limits of our fabrication equipment, we could only demonstrate metalens prototypes with up to 6 stairs, but this method can be readily extended to design metalenses with more SiN stairs and a much larger GD range, where the SiN stairs can be fabricated potentially with grayscale lithography techniques.

One of the key challenges of our fabrication is the patterning of nanoantennas on top of the SU8 spacer layer, whose morphology will be heavily affected by the SiN stairs underneath if no measures are taken. To address this issue, we compensated the height variation of the SiN stairs through our planarization process of the SU8 layer, making it possible to pattern the top nanoantennas with high quality. We believe the demonstrated fabrication techniques will facilitate the making of highly integrated meta-optical devices, potentially multifunctional as well.

To further improve our achromatic metalens design, we used frequency-dependent LAGDs to account for the meta-atom's nonlinear phase dispersion. By adding a frequency-dependent phase offset \({\varphi }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\) to the meta-atom phase spectra, we can compensate for the meta-atoms GD changes across the working frequency range, leading to minimal phase error. In addition, we developed a two-step optimization strategy to eliminate fast-oscillating features in the SiN stairs caused by meta-atoms with different stair levels, allowing the simple fabrication of the bottom layer with photolithography.

In conclusion, our technology shows a viable way of creating fast and large-aperture achromatic metalenses and brings us one step closer to practical applications where broadband achromatic operation is highly desired, such as photography with full-color imaging, broadband achromatic objective lenses for microscopy, and imaging lenses in multi-spectral imaging systems.

Methods

Numerical simulation of meta-atoms

We combined full-wave simulation with the T-matrix method to obtain the phase and GD responses of meta-atoms. First, all nanoantennas are simulated with periodic boundary conditions in a commercial finite element solver package – COMSOL. The complex Fresnel coefficients of reflection and transmission were retrieved from the model. Next, we connect the nanoantennas with the bottom SiN-SU8 layers. Here, we consider the nanoantennas as a film with known Fresnel coefficients. The transmission coefficients for the complete meta-atoms were calculated using:

Here, \({E}_{+z}\) and \({E}_{-z}\) indicate the electric field of light propagating forward (\(+z\)) and backward (\(-z\)) along the axis \(z\). The meta-atom structure starts at \(z=0\) and ends at \(z={z}_{0}\). Supplementary Fig. S1 illustrates the model configuration. The T-matrices for the nanoantenna layer and SiN layer were given as follows, respectively:

where \({t}_{a,b}\) and \({r}_{a,b}\) are the complex Fresnel coefficients of reflection and transmission for light propagating from media \(a\) to \(b\).

Fabrication of the achromatic metalenses

The metalenses were fabricated on top of a fused silica substrate. First, we deposited a 6 μm low-dispersion SiN film using PECVD with the gas ratio NH3:SiH4 = 140:35. Following that, gold markers for the alignment of the bottom stairs layer and top nanoantenna layer were defined using E-beam lithography (EBPG Vistec 5200). We used multiple contact lithography and ICP-RIE dry etching steps to define the bottom stairs. Next, we spin-coated SU8 to planarize the surface. The SU8 was back etched to decrease its thickness and then underwent thermal reflow at 220 °C to relocate and harden the material. For the final device layer, a 600 nm high-index SiN was grown by PECVD with a gas ratio NH3:SiH4 = 100:75. Finally, the top meta-atom layer was fabricated with e-beam lithography and ICP-RIE dry etching, where a 40-nm Cr layer was used as the etching mask. The fabrication process with a detailed workflow can be found in Supplementary Note S3 and Supplementary Fig. S3.

Characterization experiments of the achromatic metalenses

The characterization setup shown in Fig. 3A consists of an infinity-corrected objective lens with 0.25 NA and 10 × magnification (0.6 NA and 50x magnification for characterizing the NA = 0.27 metalens) and a 2-inch wide-angle tube lens with a 200 mm focal length that matches the objective. The objective was mounted on a motorized translation stage to scan along the optical axis. A GigE monochromatic CCD camera was placed at the back-focal plane of the tube lens for image acquisition. The fabricated metalenses were positioned on a 3-D translation stage to align with the beam. For sample illumination, a tunable wavelength Ti: Sapphire laser was coupled into the system with a single-mode fiber. The output beam was then collimated and illuminated the sample from the backside.

The experimental setup for imaging is depicted in Supplementary Fig. S4. A broadband light source was used to illuminate the USAF 1951 resolution test target. The metalens were mounted on a 3-D translation stage. To prevent light from entering nearby metalenses, as multiple metalenses were fabricated on the same chip, a 500 μm-diameter pinhole was placed right in front of the metalens. The light collected by the metalens continued to propagate through a conventional lens with a 30 mm focal length. The metalens and the second lens formed a 2f-2f optical relay system for imaging. Finally, the image was captured by a color CCD camera.

Data availability

All data presented within the Article and Supplementary Materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ni, X., Ishii, S., Kildishev, A. V. & Shalaev, V. M. Ultra-thin, planar, Babinet-inverted plasmonic metalenses. Light. Sci. Appl. 2, e72 (2013).

Pors, A., Nielsen, M. G., Eriksen, R. L. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Broadband focusing flat mirrors based on plasmonic gradient metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 13, 829–834 (2013).

Khorasaninejad, M. et al. Metalenses at visible wavelengths: Diffraction-limited focusing and subwavelength resolution imaging. Science 352, 1190–1194 (2016).

Aieta, F., Genevet, P., Kats, M. & Capasso, F. Aberrations of flat lenses and aplanatic metasurfaces. Opt. Express 21, 31530–31539 (2013).

Khorasaninejad, M., Capasso, F. Metalenses: Versatile multifunctional photonic components. Science 358, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam8100 (2017).

P. Lalanne, Chavel, P. Metalenses at visible wavelengths: past, present, perspectives. Laser Photonics Rev. 11, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201600295 (2017).

Chang, S., Guo, X. & Ni, X. Optical metasurfaces: Progress and applications. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 48, 279–302 (2018).

Chen, W. T. et al. A broadband achromatic metalens for focusing and imaging in the visible. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 220–226 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Meta-optics achieves RGB-achromatic focusing for virtual reality. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe4458 (2021).

Byrnes, S. J., Lenef, A., Aieta, F. & Capasso, F. Designing large, high-efficiency, high-numerical-aperture, transmissive meta-lenses for visible light. Opt. Express 24, 5110–5124 (2016).

Shrestha, S., Overvig, A. C., Lu, M., Stein, A. & Yu, N. Broadband achromatic dielectric metalenses. Light. Sci. Appl. 7, 85 (2018).

Ndao, A. et al. Octave bandwidth photonic fishnet-achromatic-metalens. Nat. Commun. 11, 3205 (2020).

Aieta, F., Kats, M. A., Genevet, P. & Capasso, F. Multiwavelength achromatic metasurfaces by dispersive phase compensation. Science 347, 1342–1345 (2015).

Khorasaninejad, M. et al. Achromatic metalens over 60 nm bandwidth in the visible and metalens with reverse chromatic dispersion. Nano Lett. 17, 1819–1824 (2017).

Fan, Z.-B. et al. A broadband achromatic metalens array for integral imaging in the visible. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 67 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Broadband achromatic optical metasurface devices. Nat. Commun. 8, 187 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. A broadband achromatic metalens in the visible. Nature Nanotechnol. 13, 227–232 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. High-efficiency broadband achromatic metalens for near-IR biological imaging window. Nat. Commun. 12, 5560 (2021).

Lim, S. W. D., Meretska, M. L. & Capasso, F. A high aspect ratio inverse-designed holey metalens. Nano Lett. 21, 8642–8649 (2021).

Chen, W. T., Zhu, A. Y., Sisler, J., Bharwani, Z. & Capasso, F. A broadband achromatic polarization-insensitive metalens consisting of anisotropic nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 10, 355 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Broadband polarization-independent achromatic metalenses with unintuitively-designed random-shaped meta-atoms. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.10845 (2021).

Chung, H., Chung, H., Miller, O. D. & Miller, O. D. High-NA achromatic metalenses by inverse design. Opt. Express 28, 6945–6965 (2020).

Lin, Z. & Johnson, S. G. Overlapping domains for topology optimization of large-area metasurfaces. Opt. Express 27, 32445–32453 (2019).

Lin, Z., Liu, V., Pestourie, R. & Johnson, S. G. Topology optimization of freeform large-area metasurfaces. Opt. Express 27, 15765–15775 (2019).

Avayu, O., Almeida, E., Prior, Y. & Ellenbogen, T. Composite functional metasurfaces for multispectral achromatic optics. Nat. Commun. 8, 14992 (2017).

Zhou, Y. et al. Multilayer noninteracting dielectric metasurfaces for multiwavelength metaoptics. Nano Lett. 18, 7529–7537 (2018).

Feng, W. et al. RGB Achromatic metalens doublet for digital imaging. Nano Lett. 22, 3969–3975 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Dual-layer achromatic metalens design with an effective Abbe number. Opt. Express 28, 26041–26055 (2020).

Balli, F., Sultan, M., Lami, S. K. & Hastings, J. T. A hybrid achromatic metalens. Nat. Commun. 11, 3892 (2020).

Wang, P., Mohammad, N. & Menon, R. Chromatic-aberration-corrected diffractive lenses for ultra-broadband focusing. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–7 (2016).

Meem, M. et al. Broadband lightweight flat lenses for long-wave infrared imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 21375–21378 (2019).

Xiao, X. et al. Large-scale achromatic flat lens by light frequency-domain coherence optimization - Light: Science & Applications. Light. Sci. Appl. 11, 323 (2022).

Nguyen, S. V. & Fridmann, S. Plasma deposition and characterization of thin silicon‐rich silicon nitride films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 134, 2324 (1987).

Ng, D. K. T. et al. Exploring high refractive index silicon-rich nitride films by low-temperature inductively coupled plasma chemical vapor deposition and applications for integrated waveguides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 21884–21889 (2015).

Ye, M., Peng, Y. & Yi, Y. S. Silicon-rich silicon nitride thin films for subwavelength grating metalens. Opt. Mater. Express 9, 1200–1207 (2019).

Williams, C. S., Becklund, O. A. Introduction to the Optical Transfer Function (SPIE Press, 2002).

Acknowledgements

The work was partially supported by the Sony Faculty Innovation Award and the National Science Foundation under grant agreement ECCS-2047446.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.N. conceived the idea and supervised the research. S.C. performed theoretical calculations, coding, and numerical simulations of the metalens design. Y.D., L.Z., and M.T.R. fabricated the metalenses. L.Z., M.T.R., and A.I. performed the synthesis and characterization of the Si3N4 films. S.C. conducted the characterizations of the metalenses. S.C. and X.N. analyzed the data. L. Z., Y.D., M.T.R., and A.I. provided advice and discussed the results. S.C., L.Z., and X.N. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Juejun Hu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, S., Zhang, L., Duan, Y. et al. Achromatic metalenses for full visible spectrum with extended group delay control via dispersion-matched layers. Nat Commun 15, 9627 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53701-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53701-8

This article is cited by

-

Broadband spin-unlocked achromatic meta-devices empowered by hybrid-phase cooperative dispersion engineering

PhotoniX (2025)

-

Neural array meta-imaging

eLight (2025)

-

High-performance achromatic flat lens with high NA

Light: Science & Applications (2025)

-

Ultra-compact on-chip snapshot chiral spectral imaging with dispersion-engineered chiral metalens

npj Nanophotonics (2025)

-

Free-standing bilayer metasurfaces in the visible

Nature Communications (2025)