Abstract

As the cornerstone of AI generated content, data drives human-machine interaction and is essential for developing sophisticated deep learning agents. Nevertheless, the associated data storage poses a formidable challenge from conventional energy-intensive planar storage, high maintenance cost, and the susceptibility to electromagnetic interference. In this work, we introduce the concept of metasurface disk, meta-disk, to expand the capacity limits of optical holographic storage by leveraging uncorrelated structural twist. We develop a physical twisted neural network to describe the optical behavior of the meta-disk and conduct a comprehensive lateral error analysis, where the meta-disk stores large volumes of information through internal structural multiplexing. Two-layer 640 µm x 640 µm meta-disk is sufficient to store over hundreds of high-fidelity images with SSIM of 0.8. By harnessing advanced three-dimensional (3D) printing technology, optical holographic storage is experimentally demonstrated with Pancharatnam-Berry metasurfaces. Our technology provides essential backing for the next generation of optical storage, display, encryption, and multifunctional optical analog computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At the dawn of the 21st century, the rapid development of Industry 4.0 technologies is calling for a human-machine interactive future with digital connectedness and information sharing on a scale not seen1. Data is conferred to an unprecedented resource to unearth hidden knowledge and create big deep learning agents2. Therefore, having colossal labeled data becomes preemptively emphasized, which concomitantly makes its storage very challenging. It was suggested that the amount of global data created, captured, copied, and consumed has reached 64.2 zettabytes (1 ZB = 109 TB) in 2020 and is anticipated to exceed 180 zettabytes in 20253. Current data storage still relies on conventional magnetic-electric disk, which suffers from several issues of energy consumption and vulnerability to electromagnetic interference. For example, in Google’s data centers, the energy expenditures surpass 50% of maintenance and management costs. In this context, creating a highly-secure and low-cost data storage becomes imperative and is attracting worldwide attention from commercial companies, government agencies, and academic institutions.

Forging the path ahead is optical holographic storage4. It unveils an inventive volumetric storage paradigm by harnessing the properties of light, such as its wavelength, polarization state, orbital angular momentum, and incident angle, along with versatile optical materials to store data. This is distinct from the prevailing technologies, such as solid-state drives (SSD), which steadfastly adhere to a planar storage paradigm by directing encoding data on the media surface. The advent of photonic structures and materials brings a paradigm-shift to optical storage5,6,7,8 owning to the precise control over light-matter interaction at sub-wavelength scale9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Early endeavors are many, such as metasurface display and encryption of a single holographic image, yet, the pursuit for high-density holographic storage is an endless goal18,19. Multiplexing techniques have recently found to be a superior solution20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Data encoded in photonics benefits from the selective excitation of incident light with different properties, enabling the storage of large amounts of data at the shared location in theory28,29,30,31,32. However, after one decade of proliferation, the continuous growth of storage capacity has been hindered because of many challenges in practical implementation, such as the sophisticated experimental setup and the limitation of photonic structural design. Therefore, finding a way to break this dilemma becomes fundamentally important for the continued prosperity of this field, possibly through unconventional or innovative approaches.

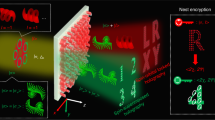

Here we present an optical metasurface disk (meta-disk) to push the capacity limit of optical holographic storage by harnessing uncorrelated structural twist degrees of freedom. Distinct from conventional multiplexing methods that rely on the variations of incident light attributes, our meta-disk stores a great number of images only with an interlayer twist. Diffractive information propagating among the meta-disk is characterized by a physical twisted diffractive neural network (TDNN), where each artificial neuron is formed by local meta-atom with different transmission/reflection coefficients. TDNNs represent a significant advance by providing a general framework to that exploits rotation as a physical weight to induce complex optical behavior, and achieve broadly unconstrained designs with rotated metasurfaces. By intricately intertwining twisted light and diffraction domain in the k-space, controllably twisted diffraction phenomena can be achieved. As a numerical testament, we consider two-layer meta-disk to vividly display two cinematic sequences, i.e., the blooming of flowers and lightning. To experimentally accentuate the concept, we utilize Pancharatnam–Berry metasurfaces as the basic neuron of TDNN and fabricate them with advanced 3D printing techniques. The display of high-precision focal point displacements and dynamic lunar phase images underscore the multifaceted potential applications in information storage. Our avant-garde approach provides a fresh perspective on twisted metasurfaces that may facilitate a myriad of applications in optical information display, processing and encryption, as well as microwave detection and ranging33,34,35.

Results

TDNN enabled high-capacity optical holographic storage

TDNN is a form of physical neural network, whose physical weights are the twist angle between multiple metasurfaces placed on a layered configuration. It offers a pathway for tunable metasurfaces and holds vast potential applications in wavefront shaping. Here holographic storage is picked as a benchmark for the captivating prospect. The fundamental working mechanism is illustrated in Fig. 1. It has been proved that multi-layer transmissive metasurfaces can be mimicked with diffractive neural network to implement a series of inference tasks36. By assembling a rotatable meta-disk at a specific interval, it efficiently achieves high-capacity holographic display. Complex diffraction takes place inside the meta-disk to generate a unique optical response. Through the continuous rotation of the meta-disk (playback), a set of diffraction domains emerges, providing fresh responses and unveiling storage holographic videos. Due to the structure multiplexing facilitated by twist operation, it not only proves to be effective in active device design, but also brings unprecedented improvements in storage capacity even in passive device.

The meta-disk composing of NMs has the capability to implement high-capacity optical holographic storage with angle-multiplexed strategy. With interlayer structural twist, it yields twin diffraction domains, resulting in a distinctive response with metasurface rotation. The network characteristics of TDNN can dynamically take shape with the varying angles of multiple layers of NMs, leading to a substantial expansion in design flexibility and freedom. Through the continuous playback of the meta-disk, a series of diffraction domains and innovative holographic videos emerges. NM, neuro-metasurface.

The intricate diffractive effects resulting from the light-metasurfaces interaction provide sufficient design freedom and substantial mapping space. However, it in-turn poses a significant challenge for optimization algorithm and computational source. For example, the design degree of freedom can exponentially reach \(100\times 100\times 100\times 100\) with only two metasurfaces containing 100 \(\times\) 100 unit cells, and continue to increase with the involvement of twist dimension. In addition, other crucial hyper-parameters of TDNN, such as spatial space, neuron period, and grid interpolation, require to be fully investigated to ensure the holographic quality with physical insight. Here, we want to particularly note that our twisted metasurfaces is different from state-of-the-art cascaded/Moiré metasurfaces37,38,39, because they are mostly confined to geometric optics and merely overlay different solutions in discrete states. Thus, they have very limited functionalities and cannot be generalized into a universal method to complex scenes.

Twin diffraction domain and TDNN architecture

To facilitate the understanding, it is essential to introduce the concept of twin diffraction domain. Structural twist operation, namely a rotation operation between two metasurfaces, leads to twin diffraction domains that are isomorphic to each other but has distinct functional scopes within their inherent diffraction domains. Illustrated in Fig. 2a is one example of metasurfaces disk, composed of a stack of metasurfaces (marked as neuro-metasurface, NM1 and NM2). According to Rayleigh–Sommerfeld diffraction, each neuro-atom on the meta-disk acts as an independent secondary source, affecting the following layer with unique diffraction domain, labeled as \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{0}\). The joint operation of NM1 and NM2 will yield distinct functionalities on the output plane, such as image recognition, holographic photography, and optical encryption. On this basis, if we add a rotation/twist angle α to NM1, the generated diffraction domain maintains consistent morphology, but its effective interaction region is switched. As the twist angle changes from \({\alpha }_{1},\,{\alpha }_{1},\,\cdots,{\alpha }_{N},\) it engenders a set of diffraction domain \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{1},\,{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{2},\,\cdots,\,{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{N}\), which originates from initial diffraction domain \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{0}\). Despite the fact that the diffraction domain is shared, the structural twist operation provides additional design degrees of freedom. Hence, the twin diffraction domain can be utilized for multifunctional and multiplexing designs.

a Schematic diagram of the TDNN operation. The structural twist produces a switching effect in the diffraction domain of NM1, allowing the construction of different functionalities on the output plane. b Schematic and comparative effectiveness of bilinear interpolation and nearest-neighbor interpolation. Taking the storage of Maxwell pattern as an example and comparing with theoretical calculation algorithms, both interpolation methods achieve high accuracy. c Flowchart of the TDNN algorithm. d Potential experimental error analysis. Varied degrees of Gaussian distribution error are induced into the phase distribution to observe its impact on the output plane. Here \(\alpha\) represents the rotation angle of NM1, \(\sigma\) represents the standard deviation of Gaussian distributed noise.

The specific TDNN training process is depicted in Fig. 2b. Initially, the phase distribution of all NMs is randomly generated, and corresponding twin diffraction domain is acquired based on the pre-set twist angle. Subsequently, by applying a multi-stage forward diffraction process using fast Fourier transform algorithm (since convolution operation in the spatial domain takes considerable computational resources, the process is expedited by transforming it into the frequency domain using Fourier Transform, followed by an inverse Fourier transform on the product), the frequency-spatial intertwining of twin diffraction domains and the neuro-atoms reveal a set of distinctive mapping images at the output plane. The disparity between each set of mapping images and the target images is characterized using two metrics: the mean squared error (MSE) and the correlation coefficient. For the loss relation across different twin diffraction fields, we perform a weighted average and utilize it as the final loss function and evaluation metrics for adjusting the transmission spectra of the NMs. By iteratively performing the aforementioned forward computation and error backpropagation40,41, the entire set of images is then comprehensively stored in the meta-disk, accompanied by gradually decreasing the MSE and increasing the correlation of the output images. Relying on the rapid computation merited by the twin diffraction domains, intricate diffraction relationships provide an extensive range of design flexibility that can be further expanded with an increase of the number of NM layers and sizes. Simultaneously, by adjusting the parameters of spatial spacing between NMs, it is possible to construct locally linked/global connected twin diffraction domains.

Consideration of lateral twist error and fabrication imperfection

Next, we specifically analyze the diffraction processes, simulate the meta-atom lateral errors (including errors caused by imperfect assumptions and approximate handling methods) in meta-disk, and explore the potential impact of unexpected fabrication errors. As a certain level of approximation involved in the TDNN algorithmic flow, we conduct lateral error analysis by integrating the physical processes of diffraction. The diffraction process can be succinctly expressed as \({U}^{l+1}={{{\mathcal{F}}}}^{-1}({{\mathcal{F}}}({{T}^{l}\cdot U}^{l})\cdot {H}_{l})\), with \({H}_{l}\) symbolizing the diffraction operator of free space based on the Rayleigh–Sommerfeld diffraction law, \({{\mathcal{F}}}\) signifying the Fourier transform operator, and \({T}^{l}\) denoting the scattering matrix. Notably, \(l\) spans from 1 to \(L\), and \(L\) denotes the total number of layers. \({U}^{l}\) denotes the \(l\) th-layer optical field, while \({U}^{l+1}\) characterizes the optical field at the next layer. As for TDNN, structural twist operation can be applied to either \({U}^{l+1}\) or \({T}^{l}\), but the induced effect is distinct. The operation on \({T}^{l}\) involves the adjustment of complex transmission spectra of the NM. Conversely, the operation on \({U}^{l+1}\) necessitates the control of the twist operations within the output space of the \(l\) th NMs, which constitutes a complex value space. As such, adding the twist operation to \({T}^{l}\) is a viable strategy to reduce potential error. In addition to the determination of the operation object, another key error comes from the grid interpolation method due to the matrix rotation. Canonical interpolation methods include nearest-neighbor interpolation and bilinear interpolation. We conduct a comparative analysis of these two approaches in Fig. 2b, taking the computational speed and accuracy into account. We display the Maxwell pattern with a two-layer meta-disk by applying the precise Rayleigh–Sommerfeld diffraction algorithm to obtain the reference meta-disk output. To select the optimal approach, we compared the TDNN algorithm based on nearest-neighbor interpolation with the one utilizing bilinear interpolation for the non-twist meta-disk profile. Subsequently, we evaluated the correlation of the final output with the reference case. The findings suggest that bilinear interpolation attains accuracy comparable to more precise algorithms, without a notable increase in computational load, by more extensively leveraging information from surrounding data points.

In addition, transfer function of free space \({H}_{l}\), governed by the Rayleigh–Sommerfeld diffraction law, is another important factor worthy considering, because it will influence the quality of holography. We refine the key control parameter Fresnel number, \(F=\frac{{a}^{2}}{\lambda d}\), where \(a\) is the neuro-atom period, \(\lambda\) represents the working wavelength, and \(d\) is the layer interval of NMs. For a certain working wavelength, we conduct parameter sweeping of \(a\) and \(d\) and generate a heatmap of Fresnel number, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S1b. It turns out that the network performs better in the highlighted region \({\mathrm{lg}}F\in \left[-5,\,-3\right]\)42. In the context of TDNN, the Fresnel number plays a pivotal role in determining the extent of connections between neuro-atoms and neuro-atoms in adjacent layers. Higher Fresnel values typically signify one-to-one mappings, whereas smaller values suggest the presence of multiple-to-one mappings, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S1a. Proper Fresnel number endows TDNN with effective expressive power (Method). To align with our subsequent processing techniques and experimental setup, the parameter set located at the pentagon’s vertex is selected.

Furthermore, the unexpected fabrication error in the experiment should also be considered. Without loss of generality, we introduce Gaussian distributed noise (with mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\)) to simulate errors in the fabrication. As a test, we load each character of the Maxwell’s equations (depicted in Supplementary Fig. S2) into different twin diffraction domain of the meta-disk and select two twist angles (corresponding to character \(E\) and \(H\)) to observe the evolution of image quality as the noise increases; see simulated results in Fig. 2c. We primarily use the correlation as the evaluation metric, and we can observe that the image quality is not significantly compromised when the standard deviation is below 30°. This indicates that our approach possesses a degree of robustness and can withstand potential processing and experimental errors.

Design of Pancharatnam–Berry metasurfaces

Designing a high-efficiency optical metasurfaces is the physical basis of TDNN, which allows for the angle-independent control of transmitted light. In the case of linear polarization, rotation will influence the response of neuro-atoms, which is challenging to be expressed mathematically and resulting in an increased computational burden to algorithm construction. Therefore, Pancharatnam–Berry phase modulation based on circularly polarized incident conditions becomes an optimal choice due to its linearly varying phase response introduced by in-plane rotation43,44,45. After the modulation of the circularly-polarized light, the output field not only undergoes a reversal of circular polarization chirality but also acquires an additional geometric phase, known as the Pancharatnam–Berry phase. In the construction of TDNN, the chirality of polarization undergoes transformations between the meta-disk. To achieve high conversion efficiency and minimize potential efficiency losses, we design rectangular polymer nanopillars with a low refractive index (n = 1.54) and a high aspect ratio, serving as the fundamental building blocks of our structure, as shown in Fig. 3a. After optimization, these nanopillars exhibit strong polarization conversion efficiency, laying the physical basis for independent phase response based on in-plane rotation angle. Utilizing Jones matrix calculations, we can introduce a local geometric phase (\(\varphi=-2\Theta\), where \(\Theta\) represents the in-plane rotation angle) for cross-circular polarization by simply rotating the in-plane nanopillar. Subsequently, we conduct numerical simulations by varying the height (\(h\)) and length (\(l\)) of the nanopillars (Fig. 3b and Methods) to investigate the amplitude of cross-polarized light transmitted through the polymer nanopillars under periodic boundary conditions. To streamline our approach, we maintain the neuro-atom periodic size of 1.25 \(\mu m\) and a width-to-length (\(w/l\)) ratio of 0.5. The results reveal that we can achieve a high level of cross-polarization efficiency by adjusting \(h\) and \(w\). On this basis, we can independently modulate the phase by varying \(\Theta\) of the 3D neuro-atoms. To simplify our laser printing design, we select nanopillars with fixed transverse dimensions and heights (w = 320 nm, \(l\) = 640 nm, and h = 3,800 nm). To enhance the diffraction efficiency, we can further reduce the spacing between nanopillars and select nanopillars with varying transverse dimensions to achieve higher absolute amplitude values.

a Schematic diagram of a neuro-atom, consisting of an SiO2 substrate and polymer nanopillars. Polarization conversion and geometric phase modulation can be achieved by varying the local rotation angle \(\Theta\). b Polarization conversion efficiency and variation as the width and height of nanopillars. To achieve highest efficiency, we select the parameter set at the red star, ensuring a high polarization conversion rate for the incident wave. c Average correlation coefficient of the stored images and training time with changes in the number of storage images. As the number increases, the training time gradually rises, while the storage correlation coefficient remains at a high level. d Video storage of a blooming and lightning. Storage examples for 36 and 40 frames are demonstrated, each of which corresponds to the storage rotation intervals of 10° and 9°, respectively.

Numerical simulations

Illustrated in Fig. 3d, e is the holographic video enabled by meta-disk. The relative intensity of two image channels can be easily manipulated by TDNN. Our TDNN algorithm incorporates can incorporate stability handling by global min-max normalizing of the target images. Several dozen frames of video images are loaded into two-layer meta-disk. By continuously rotating the meta-disk, the stored holographic video can be reconstructed. We transfer the temporal information of the original video into the continuous twist angles, allowing for a dynamic selection of twist-dependent image frames for holographic video display. To showcase the potential and diversity of our method in holographic display, we configure different rotation angle intervals for “blooming”, “lightning” and “ butterfly” design, as shown in Fig. 3d, e and Supplementary Fig. S3. We utilize a two-layer meta-disk, designed with a 1000 \({\mu m}\) spacing, and each layer consists of circular disks with the radius of 256 neuro-atoms. We demonstrate that high-quality video with a resolution of 200 ×200 can be well reconstructed on the designated output plane by sequentially twisting the metasurface with the interval \(\Delta \alpha\) (the angular difference of meta-disk corresponding to each image) of 5°/7.5° (Supplementary Videos 1, 2 and 3). Besides, it is worth noting that the number of twin diffraction domain and occupancy mode of the meta-disk is crucial as it affects the number and independence of each image, analyzed in Supplementary Fig. S1c, d.

Furthermore, we assess the capacity and scalability of the TDNN architecture. We maintain the previous design configuration and evaluate the storage precision with varying storage capacities. The results indicate that using only two layers of NM devices can efficiently store and retrieve high-precision images, with capabilities of up to \(\sim\)100 images (Fig. 3c). To verify the multiplexing ability of the TDNN for orthogonal image, the construction of classical orthogonal images (different modes of orbital angular momentum (OAM) images) as storage targets is analyzed. OAM possesses an infinite number of modes, each orthogonal to others, which naturally facilitates applications in vortex wave communication and detection. As depicted in the Supplementary Fig. S8, we utilized a three-layer metasurface configuration to examine the trend of OAM purity with increasing mode numbers. The results demonstrate that our twisted diffractive neural network achieves purity exceeding 80% for over 70 distinct OAM modes. We have also conducted a thorough assessment using standard metrics such as structural similarity index (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR). In our study, we introduced these metrics specifically to quantify the level of crosstalk present when generating OAM modes. Supplementary Fig. S9 illustrates the results of our evaluation. When we generated 70 distinct OAM modes in the case of 3 layer 512 × 512 neuro-metasurfaces, the average SSIM and PSNR values under these conditions were found to be 0.4062 and 12.3001, respectively. Due to the limited information storage density, there exists a trade-off between the quantity and quality of stored images. Additionally, to assess the scalability, we conduct a precision analysis for image storage using correlation by controlling the size of the NMs and the number of cascaded layers. With the number of layers vary from 2 to 4, and the neuro-atoms count increases from 512 × 512 to 2048 × 2048, the training correlation gradually increases from 0.8577 to 0.9969, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S4. It is proved that increasing the number of layers and the number of single-layer neuro-atoms are effective ways to expand the model. Additionally, the seamless integration of TDNN networks with frequency multiplexing patterns further extends their design capabilities. Preliminary attempts at combining multiple wavelengths multiplexing modes are explored in Supplementary Fig. S5 by utilizing neuro-atoms capable of operating across multiple frequency, where the storage utility of three frequencies is demonstrated. Further, this methodology can be enhanced by seamlessly integrating the twin diffraction domain of multiple frequencies with TDNN, thereby enabling the creation of unique and distinguishable images across different frequencies.

Fabrication and experimental results

To experimentally validate the high-volume meta-disk, we generate two large-scale samples, each measuring 640 µm × 640 µm and consisting of 512 × 512 neuro-atoms. Fig. 4a presents scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the fabricated meta-disk. Moreover, detailed top-view SEM images of specific sample areas are also depicted in Fig. 4a. In order to achieve collimation through the cascaded NMs and implement experimental rotation modulation, we design a comprehensive optical setup, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. Initially, a tightly collimated linear-polarized laser beam undergoes circular polarization conversion through a quarter-wave plate, followed by the modulation by the first-layer NM. Subsequently, using our custom-designed objective lens (used for adjusting the imaging position) in tandem with an achromatic lens (used for observing the alignment of the optical path), adjustments to the inter-layer spacing could be easily executed. The second-layer NM further modulate the beam, and holographic images are captured at the output plane using a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. During the fabrication process, we utilize state-of-the-art 3D laser printing technology46, leveraging the principles of two-photon polymerization induced by a precision femtosecond laser within a commercial photolithography system. This innovative approach allows us to meticulously craft the metasurfaces with utmost precision and quality. The detailed processing procedures and optical path calibration are depicted in Method and Supplementary Fig. S6. Simultaneously, as a reference in optical path calibration, we investigated the variation trends in the degradation of captured images under z-axis misalignment, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S7. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. S10, we observe the holographic image reconstruction when the first metasurface is shifted by 10 µm (8 pixel) in the x/y directions. In addition, we utilize rotation angles misalignment as additional design parameter. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S11, the quality of reconstructed holographic images gradually deteriorates with increasing rotational misalignment. The simulation results indicate that, as the distance/angle from accurate alignment decreases, the SSIM increases, which corresponds to higher image quality, providing critical direction in calibration.

During the experiments, we encountered various challenges such as the intricacies of experimental calibration, errors in metasurface fabrication, and the intricate coupling among neuro-atoms. These factors collectively posed a significant challenge in the display of highly complex holographic images. Consequently, we opted for relatively simpler images for the practical demonstration. As depicted in Fig. 4c–e, we develop two holographic videos, namely, dynamic focusing and lunar phase analogy, meticulously crafted to convey essential information. Consequently, rotation angle intervals \(\Delta \alpha\) were set at 12, 18, and 30o, resulting in the reconstruction of holographic imagery on the output plane. With continuous rotation angle variations, the trajectory of the focal point shifts, and the complete lunar phase changes were portrayed in the form of holograms on the CCD. It is noteworthy that the observed reduction in image quality primarily stems from the constraints in the manufactured precision of meta-disk and the inherent mechanical errors in the experimental setup. With high-throughput and high-precision 3D laser printing technology, it is possible to fabricate centimeter-scale complex-amplitude metasurfaces, thereby enabling potential for higher resolution. From the fabrication perspective, fixed-spacing glass can be used for double-sided processing to avoid alignment issues during the experiment. Alternatively, a liquid crystal spatial light modulator can be used instead of the metasurface. From the algorithmic perspective, coupling effect shall be incorporated into the network.

Discussion

In summary, we have introduced a paradigm-shift optical holographic storage, termed as meta-disk, based on the TDNN. By virtue of the structural multiplexing, twin diffraction domain offers additional design flexibility and significantly enhances information storage and encryption capability. In addition to dynamic focusing and holographic storage, TDNN holds the promise of evolving into the next generation of nano film. Furthermore, this flexible multiplexing method can synergistically combine with other multiplexing techniques for exponential capacity gain, such as the integration with wavelength and polarization multiplexing. As a groundbreaking information storage technology, it has the potential to become a key application in virtual reality, lens systems, and optical encryption. Moving forward, to tackle the experiment challenges such as metasurface coupling, we are investigating a global design of meta-disk by involving metasurface coupling effect through graph neural network47,48,49. This approach will enable us to demonstrate a more advanced and higher-quality holographic multiplexing system, better reflecting the feasibility of our proposed concept.

We anticipate broader applications of TDNN in vast fields, including 6G communication, photonic computing, image recognition, biomedicine, and quantum computing50,51,52. This work also provides inspiration for existing research on Moiré metasurfaces37,38,39,53,54 and diffraction neural network55,56,57. Within the realm of photonics computing58, prevailing multiplexing practices predominantly center around the reiteration of optical properties, thereby imposing substantial constraints on design freedom and flexibility. In contrast, TDNN strategy goes to great lengths to thoroughly probe the diffraction domain, emancipating itself from the shackles of intricate optical devices and infusing the potential for pioneering opportunities. Meanwhile, our work presents a design approach for optical computing devices capable of performing multiple tasks59, and holds the potential to enhance design flexibility when combined with nonlinear optical devices60.

Methods

Fast Fourier transform algorithm

The integral form of Rayleigh–Sommerfeld diffraction can be represented as follows,

Analogous to the convolution formula,

We can define the impulse response in this way,

This allows the integral of Fresnel diffraction to be transformed into the convolution of terms \({u}_{0}({x}_{0},\,{y}_{0},\,0)\) and \(h\left(x,y\right)\). Integrating irrelevant terms in the impulse response leads to

On the other hand, since performing convolution in the spatial domain is computationally expensive, it is typically preferable to switch to the k-space for calculations. According to the spectral properties, convolution in the spatial domain is equivalent to multiplication in the k-space. Therefore, it is necessary to perform a Fourier transform on both \({u}_{0}({x}_{0},\,{y}_{0},\,0)\) and \(\exp [\frac{{j}_{k}}{2d}({x}^{2}+{y}^{2})]\), followed by an inverse Fourier transform on their product. Considering the above, the fast Fourier transform algorithm for Fresnel diffraction integration is

Rotation interpolation algorithm

The calculation of rotated coordinates involves transforming from the original coordinates \((x,{y})\) to the rotated coordinates \((x^{\prime},{y}^{\prime} )\), given the rotation angle \(\Theta\). The mathematical expression for the rotation transformation is as follows:

When it comes to the interpolation for rotated images, the nearest-neighbor interpolation method and bilinear interpolation method provide efficient and accurate implementations. Here are their specific algorithmic procedures. Nearest-neighbor interpolation is a simple interpolation method based on the principle of finding the nearest neighbor in the original data for a given target point. The mathematical expression is as follows:

Here, \(\left\lfloor {x}^{{\prime} }+0.5\right\rfloor\) and \(\left\lfloor {y}^{{\prime} }+0.5\right\rfloor\) represent the nearest integers to \({x}^{{\prime} }\) and \({y}^{{\prime} }\), respectively.

Bilinear interpolation is a method that uses the surrounding four neighbors of the target point for interpolation. This method is based on linear interpolation and involves two linear interpolations, one along the horizontal direction and one along the vertical direction. The value for bilinear interpolation is,

Here, \(\alpha={x}^{{\prime} }-\left\lfloor {x}^{{\prime} }\right\rfloor\) and \(\beta={y}^{{\prime} }-\left\lfloor {y}^{{\prime} }\right\rfloor\) represent the offsets of the target point in the horizontal and vertical directions in the rotated image.

Loss function and evaluation criteria

Mean squared error (MSE) is a commonly used loss function in regression tasks. It measures the average squared difference between the predicted values, denoted as \(\hat{y}\), and the actual values, denotes as \(y\). The formula for MSE is given by

Here, \(n\) is the number of images pixels, \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) represents the model prediction for the \(i\)-th pixel, and \({y}_{i}\) is the actual value for the \(i\)-th pixel. A lower MSE indicates better model performance as it reflects smaller differences between predicted and actual values.

The correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables. In the context of evaluating model performance, particularly in regression tasks, we are interested in the relationship between model outputs and actual labels. The Pearson correlation coefficient is commonly used and is calculated by the following formula,

Here, \({x}_{i}\) and \({y}_{i}\) are the model outputs and actual pixels, respectively. \(\bar{x}\) and \(\bar{y}\) are their respective means. The correlation coefficient ranges from −1 to 1, where values closer to 1 indicate a stronger linear relationship.

Derivation of optimal range of the Fresnel number

Let \(r\) be the distance of neuro-atom on one layer and the other on the next layer, we can simply get \(r=\sqrt{{d}^{2}+{(N\cdot a)}^{2}},\) where \(N\) is the layer’s dimension of one side and \(a\) is the periodic of neuro-atom. The neuro-atom receive the information that maximum phase difference is determined by the diffraction. It should satisfy the following inequality

which can be rewritten as

Substitute the expression of \(r\) into it, then we can get

In the present case, \(\frac{\lambda }{d}\) can be a negligible amount because it’s very small value. We can further get

On the other hand, since the shape of each neuro-atom can be considered as square, the energy distribution of each neuro-atom diffraction pattern can be expressed as \(I\left(x,{y}\right)={I}_{0}{{sinc}}^{2}(\alpha ){{sinc}}^{2}(\beta )\), where \(\left(x,{y}\right)\) is the coordinate of neuro-atom at output plane, and \(\alpha=\frac{\pi {xa}}{\lambda d}\), \(\beta=\frac{\pi {ya}}{\lambda d}\). Its zero point satisfies the condition

The maximum \(x\) or \(y\) is supposed to be \(N\). Then we can get the inequality that

The reference values for \({n}_{1}\) and \({n}_{2}\) are both 242. In summary, the TDNN can reach a good performance when \(F\in (\frac{2{n}_{1}}{{N}^{2}},\,\frac{{n}_{2}}{N})\). In this work, we let \(N=512\), and get \(F\in (1.5\times {10}^{-5},\,4\times {10}^{-3})\).

Numerical design and optimization of neuro-atoms

Numerical simulation of the amplitude responses of the neuro-atom was carried out using in-house-developed rigorous coupled-wave analysis (RCWA61). The scattering parameters (S-parameters) of a polymer-based neuro-atom with periodic boundary conditions for polarization along the long transverse axis \({t}_{l}\) and the short transverse axis \({t}_{s}\) were obtained from the zeroth-order transmission coefficient. According to our analytical results based on Jones matrix calculus, the conversion efficiency was calculated as \({CE}={|\frac{{t}^{l}-{t}^{s}}{2}|}^{2}\).

3D laser printing of phase-modulated meta-disk

3D laser printing of polymer-based phase-modulated meta-disks was successfully accomplished through two-photon polymerization within a tightly focused femtosecond laser beam. This achievement utilized a commercial photolithography system (Photonic Professional GT2, Nanoscribe). The polymer metasurface samples were crafted on glass substrates using an IP-Dip resist (Nanoscribe) and a high numerical aperture objective (Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40 Oil DIC, Zeiss). Optimal printing parameters included a laser power of \(60{mW}\) and a scan speed of \({6500\mu {ms}}^{-1}\). Following laser exposure, the samples underwent development by immersion in propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min, isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min, and methoxynonafluorobutane (Novec 7100 Engineered Fluid, 3 M, with the methoxy group OCH3 positioned at the end of methoxynonafluorobutane) for 2 min. Subsequently, the fabricated samples were air-dried through evaporation. To enhance the mechanical strength of the polymer nanopillars, characterized by very high aspect ratios, small hatching (laser movement step in the transverse directions: 20 nm) and slicing (laser movement step in the longitudinal direction: 100 nm) distances were employed in our 3D optical printing of phase-modulated metasurfaces. To significantly boost fabrication throughput, the galvonometer mirror scanning mode was chosen, and each scanning field was confined to a square unit cell of 125 µm \(\times\) 125 µm to minimize stitching errors and optical aberrations.

Optical path calibration module

Calibrating the position of the multi-layer NMs is a crucial step to guarantee the success of the experiment. We have established two calibration modules to precisely align it, as shown in Supplementary Figs. S6 and S12. Module calibration can be performed based on the real-time CCD images transmitted to the PC. Calibration Module 1: Turn on LED1 and adjust the lateral and longitudinal positions of NM1 through Objective1 until the spot in the CCD1 is in the center and the imaging of NM1 is clear. Open the laser lens to fine-tune the intensity, adjust the spot to the center after adjusting the laser intensity, and then turn off LED1. Calibration Module 2: Turn on LED2 and turn off the laser. Adjust the lateral and longitudinal positions of NM2 through the CCD2 to overlap the spot with the previous level’s spot center through Objective2. Then turn off LED2, turn on the laser, and adjust the longitudinal position of NM2 to ensure the spot size is appropriate. Finally, turn on CCD3 and adjust the front and back position knobs of Achromatic Lens 1 for focusing until the received image is the clearest.

Data availability

Data presented in this publication is available on Figshare with the following identifier (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19602145.v1).

Code availability

The codes used in the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Industry 4.0 metaverse unlocked: How AR/VR, AI and 3D technology are powering the next Industrial Revolution. Telecom Ramblings. https://www.telecomramblings.com/2023/10/industry-4-0-metaverse-unlocked-how-ar-vr-ai-and-3d-technology-are-powering-the-next-industrial-revolution/ (2023).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Taylor, P. Data Growth Worldwide 2010-2025. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/871513/worldwide-data-created/ (2023).

Heanue, J. F., Bashaw, M. C. & Hesselink, L. Volume holographic storage and retrieval of digital data. Science 265, 749–752 (1994).

Gu, M., Li, X. & Cao, Y. Optical storage arrays: a perspective for future big data storage. Light Sci. Appl. 3, e177 (2014).

Monge, R., Delord, T. & Meriles, C. A. Reversible optical data storage below the diffraction limit. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 202–207 (2024).

Wiecha, P. R. et al. Pushing the limits of optical information storage using deep learning. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 237–244 (2019).

Ma, Y. et al. One-hour coherent optical storage in an atomic frequency comb memory. Nat. Commun. 12, 2381 (2021).

Yu, N. et al. Light propagation with phase discontinuities: Generalized laws of reflection and refraction. Science 334, 333–337 (2011).

Qian, C. et al. Dynamic recognition and mirage using neuro-metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2694 (2022).

Jia, Y. T. et al. A knowledge-inherited learning for intelligent metasurface design and assembly. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 82 (2023).

Lin, D. et al. Dielectric gradient metasurface optical elements. Science 345, 298–302 (2014).

Arbabi, A. et al. Dielectric metasurfaces for complete control of phase and polarization with subwavelength spatial resolution and high transmission. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 937–943 (2015).

Ni, X., Kildishev, A. V. & Shalaev, V. M. Metasurface holograms for visible light. Nat. Commun. 4, 2807 (2013).

Fan, Z. X. et al. Homeostatic neuro-metasurfaces for dynamic wireless channel management. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn7905 (2022).

Yu, N. F. & Capasso, F. Flat optics with designer metasurfaces. Nat. Mater. 13, 139–150 (2014).

Cai, T. et al. Ultrawideband chromatic aberration-free meta-mirrors. Adv. Photon. 3, 016001 (2021).

Qu, G. et al. Reprogrammable meta-hologram for optical encryption. Nat. Commun. 11, 5484 (2020).

Mueller, Balthasar et al. Metasurface polarization optics: Independent phase control of arbitrary orthogonal states of polarization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 113901 (2017).

Xiong, B. et al. Breaking the limitation of polarization multiplexing in optical metasurfaces with engineered noise. Science 379, 294–299 (2023).

Luo, X. et al. Metasurface-enabled on-chip multiplexed diffractive neural networks in the visible. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 158 (2022).

Bao, Y. et al. Full-colour nanoprint-hologram synchronous metasurface with arbitrary hue-saturation-brightness control. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 95 (2019).

Ma, W. et al. Pushing the limits of functionality-multiplexing capability in metasurface design based on statistical machine learning. Adv. Mater. 34, 2110022 (2022).

Xiong, B. et al. Realizing colorful holographic mimicry by metasurfaces. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005864 (2021).

Deng, L. et al. Structured light generation using angle-multiplexed metasurfaces. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2300299 (2023).

Wan, S. et al. Angular-multiplexing metasurface: building up independent-encoded amplitude/phase dictionary for angular illumination. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2101547 (2021).

Deng, Z. et al. Full-color complex-amplitude vectorial holograms based on multi-freedom metasurfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910610 (2020).

Ren, H. et al. Complex-amplitude metasurface-based orbital angular momentum holography in momentum space. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 948–955 (2020).

Ouyang, X. et al. Synthetic helical dichroism for six-dimensional optical orbital angular momentum multiplexing. Nat. Photon. 15, 901–907 (2021).

Fang, X., Ren, H. & Gu, M. Orbital angular momentum holography for high-security encryption. Nat. Photon. 14, 102–108 (2019).

Kamali, S. M. et al. Angle-multiplexed metasurfaces: encoding independent wavefronts in a single metasurface under different illumination angles. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041056 (2017).

Zhao, R. et al. Multichannel vectorial holographic display and encryption. Light Sci. Appl. 7, 95 (2018).

Ma, W. et al. Deep learning for the design of photonic structures. Nat. Photon. 15, 77–90 (2021).

Fan, Z. X. et al. Transfer-learning-assisted inverse metasurface design for 30% data saving. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 024022 (2022).

Jia, Y. T. et al. In situ customized illusion enabled by global metasurface reconstruction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109331 (2022).

Lin, X. et al. All-optical machine learning using diffractive deep neural networks. Science 361, 1004–1008 (2018).

Wei, Q. et al. Rotational multiplexing method based on cascaded metasurface holography. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2102166 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Moiré metasurfaces for dynamic beamforming. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo1511 (2022).

Cai, X. et al. Dynamically controlling terahertz wavefronts with cascaded metasurfaces. Adv. Photon. 3, 036003 (2021).

Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.04747 (2016).

Kingma, D. & Ba, J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980 (2014).

Zheng, M., Shi, L. & Zi, J. Optimize performance of a diffractive neural network by controlling the Fresnel number. Photonics Res. 10, 2667 (2022).

McDonnell, C. et al. Functional THz emitters based on Pancharatnam-Berry phase nonlinear metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 12, 30 (2021).

Tymchenko, M. et al. Gradient nonlinear pancharatnam-berry metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 207403 (2015).

Xie, X. et al. Generalized Pancharatnam-Berry phase in rotationally symmetric meta-atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 183902 (2021).

Grebenyuk, S. et al. Large-scale perfused tissues via synthetic 3D soft microfluidics. Nat. Commun. 14, 193 (2023).

Wu, O. et al. General characterization of intelligent metasurfaces with graph coupling network. Laser Photonics Rev. 2400979 (2024).

Lin, P. et al. Assembling reconfigurable intelligent metasurfaces with synthetic neural network. IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag. 72, 5252–5260 (2024).

Lin, P. et al. Enabling intelligent metasurfaces for semi-known input. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 178, 82–91 (2023).

Qian, C. & Chen, H. A perspective on the next generation of invisibility cloaks—intelligent cloaks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 180501 (2021).

Wainberg, M. et al. Deep learning in biomedicine. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 829–838 (2018).

Zhao, M. et al. A 3D nanoscale optical disk memory with petabit capacity. Nature 626, 772–778 (2024).

Fan, Z. et al. Spatial multiplexing encryption with cascaded metasurfaces. J. Opt. 25, 125105 (2023).

Wu, Z. L. & Zheng, Y.B. Moiré metamaterials and metasurfaces. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 1701057 (2018).

Qian, C. et al. Deep-learning-enabled self-adaptive microwave cloak without human intervention. Nat. Photon. 14, 383–390 (2020).

Li, J. X. et al. Spectrally encoded single-pixel machine vision using diffractive networks. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd7690 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. A programmable diffractive deep neural network based on a digital-coding Metasurface Array. Nat. Electron. 5, 113–122 (2022).

Zhou, T. et al. Large-scale neuromorphic optoelectronic computing with a reconfigurable diffractive processing unit. Nat. Photon. 15, 367–373 (2021).

Li, X. R. et al. Plasmonic photoconductive terahertz focal-plane array with pixel super-resolution. Nat. Photon. 18, 139–148 (2024).

White, A. D. et al. Integrated passive nonlinear optical isolators. Nat. Photon. 17, 143–149 (2023).

Hench, J. & Strakoš, Z. The RCWA method - a case study with open questions and perspectives of algebraic computations. Electron. Trans. Numer. Anal. 39, 331–357 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work at Zhejiang University was sponsored by the Key Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology under Grants No. 2022YFA1404704 (H.C.), 2022YFA1404902 (H.C.), and 2022YFA1405200 (H.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NNSFC) under Grants No.11961141010 (H.C.) and No. 61975176 (H.C.), the Top-Notch Young Talents Program of China and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (H.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Q., Z.F., and H.C. conceived the idea of this research. Z.F. performed the simulation and experiment. Y.F. assisted with the setup of the experimental platform. Y.J. assisted in the design of the network. Z.F. and C.Q. wrote the paper. E.L. and R.F. shared their insights and contributed to discussions on the results. C.Q., H.Q. and H.C. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yongmin Liu, XiaoHong Sun, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Z., Qian, C., Jia, Y. et al. Holographic multiplexing metasurface with twisted diffractive neural network. Nat Commun 15, 9416 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53749-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53749-6

This article is cited by

-

The Principle of Holographic Encryption Based on Metasurfaces and Its Research Progress

Journal of Electronic Materials (2026)

-

Dispersion-engineered compact twisted metasurfaces enabling 3D frequency-reconfigurable holography

PhotoniX (2025)

-

Broadband unidirectional visible imaging using wafer-scale nano-fabrication of multi-layer diffractive optical processors

Light: Science & Applications (2025)

-

A guidance to intelligent metamaterials and metamaterials intelligence

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Programmable metasurfaces for future photonic artificial intelligence

Nature Reviews Physics (2025)