Abstract

Shifting precipitation regimes are a well-documented and pervasive consequence of climate change. Subsistence-oriented communities worldwide can identify changes in rainfall patterns that most affect their lives. Here we scrutinize the importance of human-based rainfall observations (collated through a literature review spanning from 1994 to 2013) as climate metrics and the relevance of instrument-based precipitation indices to subsistence activities. For comparable time periods (1955-2005), changes observed by humans match well with instrumental records at same locations for well-established indices of rainfall (72% match), drought (76%), and extreme rainfall (81%), demonstrating that we can bring together human and instrumental observations. Many communities (1114 out of 1827) further identify increased variability and unpredictability in the start, end, and continuity of rainy seasons, all of which disrupt the cropping calendar, particularly in the Tropics. These changes in rainfall patterns and predictability are not fully captured by existing indices, and their social-ecological impacts are still understudied.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shifting precipitation regimes are a well-documented consequence of climate change, known to affect crop production, food security, the incidence of water-borne diseases and human health1,2,3,4,5,6. However, it is difficult to assess how regime shifts vary across regions7,8 since precipitation patterns and volumes both differ and are changing differently across the globe3. In several regions around the world, precipitation patterns simulated by climate models also remain uncertain, particularly at the local level3,9. The largest uncertainties among model projections occur in regions where a shift in the sign of change in precipitation volumes is expected3,10,11. These uncertainties contribute to precluding the interpretation of the ongoing and future local climatic changes and their resulting impacts to local communities.

Using climatic data to assess the social-ecological impacts of climate change requires an understanding of how rainfall patterns affect natural and agro-ecosystems as well as the human communities that depend on these ecosystems for their subsistence12. Seasonal rainfall cycles set the timing over which plants synchronize their phenology, animals adjust their mating seasons and farmers decide their cropping calendar. Any future change to seasonality and the associated intensity and volume of rainfall will impact species distributions, crop production and human societies (e.g., refs. 13,14,15,16). Thus, one challenge for projecting future climate change involves developing indices that capture characteristics of precipitation that are most important to human societies, especially those that are dependent on reliable characteristics of rainfall for maintaining their food provisioning as are thousands of subsistence-oriented communities worldwide.

Subsistence-oriented communities include indigenous and non-indigenous people whose livelihood and culture largely depend on, and are interlinked with, the local environment4. Because of this interconnectedness, these communities have been shown to have a deep understanding of broad environmental processes and functions and their changes, based on the accumulation of experiences, adaptive learning and intergenerational sharing of observations4. In the current race against climate change, many researchers have recognised the importance of the ecological knowledge of these communities to better understand how the changing climate is impacting local environments and peoples17,18. In this paper, we combine this knowledge with climate data, not to validate it19 but to increase our overall understanding of local climatic changes and to identify which of those changes are more relevant for local communities.

Here, we explore how to bridge the gap between information conveyed by instrumental records and the information needed by communities trying to adapt to climate change. We compare observations by subsistence-oriented communities4 with several indices of precipitation characteristics from instrumental observations. Between 2012 and 2013, we assembled these human observations of changes in precipitation and drought by conducting a global meta-analysis4 spanning sources from 1994 to 2013 and including human recollections up to 40 years prior to the reporting dates. We performed the meta-analysis using peer-reviewed and grey literature that reported observations of climatic changes made by subsistence-oriented communities. We then georeferenced these observations and compared them to spatial patterns of climatic indices derived from instrument-based data. These indices include (1) Total Precipitation20 (PRCPTOT shortened here for simplicity to TP); (2) extreme rainfall20 (R95p); (3) drought as defined by Consecutive Dry Days20 (CDD) and (4) drought as defined by the Palmer Drought Severity Index21 (PDSI) (the detailed explanation of these indices is reported in the cited references while technical details on the databases can be found in Supplementary Table 1). We also visually compared human observations with changes in the Dimensionless Seasonality Index (DSI)2,22, which measures the seasonal distribution of rainfall (changes in DSI can indicate either a variation in annual rainfall or seasonal differences in rainfall amounts). All these indices are estimated from global instrument-based records for the period of 1955–2005, which we deem to be roughly comparable to the time period covered by the human observations4. By comparing instrument-based metrics and human observations at every location, we identify regions of agreement and disagreement between the two types of data. We then discuss what we can learn from this comparison and explore how local observations can complement instrumental indices. Finally, we discuss what kind of precipitation information (i.e., new climatic measures) could help local communities be better prepared to plan for, cope with and adapt to climate change.

Results

Matching precipitation data with human observations

The collated human observations that pertain to precipitation changes total 3753 and cover 129 countries, with 1827 localities across seven Ecozones (Fig. 1a). At greater than 60% of these locations, multiple precipitation changes were observed, such as the co-occurrence of increased droughts and altered rainfall patterns (hotspots of changes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). The most reported observations (N = 1114) are about change in patterns of rainfall followed by changes in amounts of rainfall (Supplementary Table 2). Altered patterns and predictability of rains are less commonly reported in the Northern Hemisphere and are mostly reported for tropical and subtropical regions of Africa and Asia, where precipitation generally has a more defined seasonality2,23 (Fig. 1b, c).

A Ecozonal distribution of selected rainfall observation types made in subsistence-oriented communities and their agreement with instrument-based metrics; (B) Distribution of subsistence-oriented communities reporting changes in rainfall patterns (black circles), superposed on the decadal trend in Dimensionless Seasonality Index (DSI)2,22 (1955–2005). Solid grey lines indicate −23.5 and 23.5 degrees latitude (Tropics). Dashed lines indicate −35 and 35 degrees latitude (Subtropics); (C) Distribution of subsistence-oriented communities reporting changes in rainfall predictability (black circles), superposed on the decadal trend in DSI2,22 (1955–2005). Solid grey lines indicate −23.5 and 23.5 degrees latitude (Tropics). Dashed lines indicate −35 and 35 degrees latitude (Subtropics). TP Total Precipitation, R95p Annual total precipitation from days >95 percentile, CDD Consecutive Dry Days, PDSI Palmer Drought Severity Index. Human observations are provided as source data.

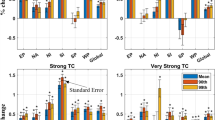

Of the locations with sufficient instrumental data, many human observations show agreement with precipitation indices both globally and regionally (Figs. 1a and 2 and Table 1) although we could not reject the null hypothesis of independence between the two datasets using a Pearson’s Chi-squared test (Supplementary Fig. 2). Globally, we find that observations match better with the metrics that intuitively describe the observed phenomenon (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). For example, we observe strong agreement between observations of changes in drought and the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) (76%), in extreme rainfall and the R95p index (81%), and in observed changes in general rainfall and Total Precipitation (TP) (72%). We note that there is agreement whether we are considering metrics of gradual change (TP, PDSI) or metrics of changes in extreme climate events (R95p), suggesting that humans capably detect changes in both the mean and the extremes independently24 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 3–5).

A TP (GPCC version 7; resolution: 2.5 × 2.5) with human observations of rainfall; (B) R95p (GHCNDEX; resolution: 2.5 × 2.5) with human observations of extreme rainfall; (C) CDD (GHCNDEX; res. 2.5 × 2.5) with human observations of drought; (D) PDSI (Dai et al.21; resolution: 2.5 × 2.5) with human observations of drought. Note: there is a match if the sign of the climate trend at each location is consistent with the sign of the human observation. TP Total Precipitation, R95p Annual total precipitation from days >95 percentile, CDD Consecutive Dry Days, PDSI Palmer Drought Severity Index, GPCC Global Precipitation Climatology Centre, GHCNDEX gridded temperature and precipitation climate extremes indices from the Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN) dataset, HadEX3 dataset of gridded station-based climate extremes indices. Human observations are provided as source data.

At regional levels (Fig. 1a), agreement between human observations and instrumental precipitation metrics is better in Ecozones where respective climate impacts are common. For example, drought and PDSI match best in the Afrotropic region (91%); general rainfall and TP match best in the Afrotropic and Palearctic regions (85% and 76%, respectively), and extreme rainfall and R95p match best in the IndoMalay region (87%). In the Afrotropic and Palearctic regions, the amounts of rainfall over specific periods might be relevant for agriculture or animal husbandry (i.e., greening of pastures), which could explain the high match of human observations for total precipitation or drought in these regions. The IndoMalay region encompasses countries that are heavily influenced by seasonal precipitation as part of the southeast monsoon, and in these areas, subsistence-oriented people are likely to depend on (and therefore monitor) the timing and intensity of heavy monsoon rains. These findings are consistent with previous research (e.g., refs. 25,26) suggesting that people are more attuned to rainfall changes that affect their activities most directly, and that observations of these types of changes therefore tend to be the most accurate.

We also compared the human observations with sub-periods (1975–2005 and 1985–2005) within our full study period (1955–2005) (Table 2 and Fig. 3). We note the possibility of a stronger alignment between observed and instrumental data as the temporal scope of available data increases – at least for the directly corresponding measurement indices (in bold in Table 2). This increased alignment over longer time periods might suggest that people’s observations tend to ‘average’ the trends over long periods of time. At least for annual rainfall (TP), this observation seems to validate our assumption of 50 years as the period of relevance for human observations, offering potentially useful guidance for others who wish to incorporate human observations into their data analyses. While the time span of human observations necessarily varies due to differences in year of data collection, starting period of the observed change and age of the informants, these observations nevertheless document similar changes in precipitation. One unexpected result is the fewer number of matches (Table 2) for some indices in the 30-year time series compared to the 20-year time series. We expected the number to consistently increase as more data are available i.e., the ‘matches’ for the 30-year time series should be at least as many as for the 20-year time series. We suggest that this happens because, for these indices, the direction of change is highly variable for instrumental trends27, i.e., the sign of change switches across the three different time series for several grid cells, which is consistent with the increased unpredictability observed by subsistence-oriented people.

A Human observations and TP calculated for the period 1955–2005; (B) Human observations and TP calculated for the period 1975–2005; (C) Human observations and TP calculated for the period 1985–2005. Interestingly, there are fewer gridboxes with agreement for the shorter time series (1985–2005) and some shifting of gridboxes between the bottom two panels (1975–2005 and 1985–2005), but overall not much change in the percent agreement. Note: Human observations are provided as source data.

Comparing human observations with multiple indices can provide additional information that is not evident when comparing with only one index. In the IndoMalay, Nearctic and Palearctic regions, observations of extreme rains match with both R95p (extreme rainfall) and CDD (dry conditions). In these regions, people report increases in drought and extreme rainfall at the same locations. Since extreme rainfall events are typically brief while drought is more prolonged, this pattern suggests people are witnessing more short, intense rains interrupted by longer dry periods. A second interesting feature of these comparisons is that the drought perceived by local communities does not always match equally with measures of relative dryness (PDSI) and lack of rainfall (CDD) in different Ecozones. PDSI corresponds more frequently with the human observations than does CDD. This could be due to two reasons. First, since people in agrarian cultures depend on soil conditions for food production, they likely have a complex conceptualisation of drought4,28 that is captured better by the PDSI index, which considers both precipitation and soil moisture. Second, the sparseness of the CDD data drives our results (Table 1). Relaxing the CDD resolution to the coarser HadEX2 dataset results in a substantially larger number of locations with overlapping data but with more incomplete recording periods (Supplementary Fig. 4). The HadEX3 dataset, instead, has a higher resolution and better data coverage29 with a higher match with human observations of drought (n = 631 with 70% match vs n = 199 and 44% match for GHCNDEX). This difference could be explained partially by the fact that the rainfall data that come from these datasets are assembled using largely independent measuring stations to which different levels of quality control and correction are applied29. All these datasets, however, do not cover key regions where drought is relevant (i.e., sub-Saharan Africa) (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 4) and where people are observing it. Our results suggest that many subsistence-oriented communities tend to integrate the impacts of climate change on precipitation and soil moisture, but also that, in the absence of instrument-based data, human observations provide a first-order interpretation of ongoing changes at local levels.

What we can learn from human observations

Our comparisons reveal some spatially distinct patterns in human observations and trends in precipitation indices (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 3–5). We compared human observations of general rainfall with measured trends in total surface precipitation, and we identified mismatches between these two sets of data (Fig. 2a, purple dots) primarily in Eastern Africa and the Eastern part of the Indian peninsula in Southeast Asia. We also found mismatches between observations of drought and trends in PDSI in these two areas (Fig. 2d), along with a third hotspot of disagreement in Indochina. Data coverage for the other drought index CDD is quite sparse, yet the same three areas suggest similar disagreement between drought and CDD (Fig. 2c).

Several factors could create these mismatches between human observations and instrument-based indices of precipitation, some of which apply to all regions, and some of which are region specific (i.e., Eastern Africa and the Eastern side of the Indian peninsula in Southeast Asia). The first potential cause is a mismatch in temporal scale. In this study, we assumed that human observations represent a period of about fifty years and our comparison of sub-periods described above appears to support this assumption, but these observations could represent longer or shorter periods4. When considering precipitation, for example, variability in patterns can depend strongly on the time period chosen. The IPCC report3 outlines a general increase of precipitation rates in the Tropics over the first decade of the 21st century, but a drying trend before then. As a result, due to these trends cancelling each other out, the general global trend for many areas in this latitudinal range shows no change or a minimal change between 1951 and 2008. This general global trend would be inconsistent with the experiences of local communities where a variable climate is certainly perceived.

A second potential reason for mismatches could relate to a sparse cover of instrumental recording stations or incomplete recording periods near the locations of human observations. The network of stations contributing to the global rainfall data are unevenly distributed3, a challenge for local comparisons with precipitation behaviour. For instance, for all the measurement indices best corresponding with human observation types (numbers in bold in Table 1 and Table 2) that have more than 500 instances where human observations and instrumental observations overlap (numbers in brackets in Tables 1 and 2), matches are high (mostly above 60%). The HadEX2 dataset contains large data gaps in Africa, which have only partially been covered with the HadEX3 dataset27,30 and several meteorological stations have incomplete time series of precipitation data in Eastern Africa2. This region corresponds with a clustering of mismatches between human observations and instrumental data, as well as documented mismatches between simulated and instrumental precipitations patterns, termed the “Eastern African Paradox”31. Similarly, the GHCNDEX dataset includes a very limited number of gauging stations in the Himalaya region29 allowing a comparison only with distant instrumental observations that might not reflect local changes in rainfall. Particularly in such regions with very limited instrumental data the human observations can provide valuable insights.

A third reason is that local, non-climatic factors, such as complex topography, microscale rain-shadows and other contributors to microclimates can create highly localised patterns of precipitation that are difficult to match when instrumental stations are located at a distance from the community. For example, the impact of local topography and inland water basins32 (i.e., Lake Victoria in Eastern Africa, the Himalaya in Asia) could hinder matches between human observations and instrument-based records that, while seemingly close, are detecting very different patterns of precipitation. Additionally, in some cases, other anthropogenic factors (i.e., deforestation in Eastern Africa, dust storms in some Asian regions) might have changed precipitation patterns locally33,34. but are not detected due to the low density of gauging stations. For this analysis, in some cases we had to compare human observation with instrumental observations at hundreds of kilometres of distance. This effect is evident in the different percentages of matches when we consider different datasets or the same datasets at different resolutions (see Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 3–5). Furthermore, most of the mismatches are located on the margins of areas where there is agreement and a shift from wetter toward drier, possibly indicating that drier conditions are more extensive than suggested by the instrumental data.

A fourth possibility is that humans and instrument-based indices are simply observing different features of precipitation. It is possible that people conceptualise a specific change in rainfall differently than the same precipitation characteristic measured by the indices we consider here. People may perceive “lack of rain” as strictly related to the timing or duration of rainfall relevant to the farming calendar (see also Savo et al.4). Indeed, Funk et al.32 showed that the amounts of precipitation changed over the various seasons in Eastern Africa (one of the regions where we had a clustering of mismatches), and many communities in this area also reported changes in patterns and increased unpredictability of rainfall (Fig. 1c). Insufficient rainfall during the growing season will likely be interpreted as “lack of rain” by a farmer, regardless of rainfall amounts during the other seasons. Thus, while the matches between human observations and precipitation indices can confirm the value of local knowledge, the mismatches can highlight regions where indices are not conveying information that is meaningful for local communities. This suggests that comparison with human observations provides an added value to the assessment of ongoing changes in precipitation patterns (and their impacts), and that regions where people are observing different trends in rainfall than those depicted by coarse global averaging of precipitation data require finer characterisation.

Unpredictability and changing patterns of rainfall

The increased unpredictability and variability of rainfall patterns35 (1114 out of 3753 observations; Figs. 1b, c and 4) is a recurrent human observation that is not easily captured by conventional precipitation indices. Our visual comparison between the changes (decadal trend) in the annual Relative Entropy, annual rainfall, Dimensionless Seasonality Index (DSI)2,22 and human observations of changes in rainfall patterns (Fig. 4), illustrates a prevalence of seasonality changes over the last 50 years2. However, one factor not fully captured by the DSI or other indices is the increased unpredictability of rainfall which pertains, in the context of this paper, to the usual start, ending and persistence (continuous rains vs rains interrupted by dry spells) of the rainy season. In this sense, unpredictability partially corresponds to the interannual variability of rainfall36 but also to the fact that people are no longer able to use critical seasonal clues (e.g., interpretations of wind directionality and cloud formations) to predict the arrival or behaviour of rainfall, which hinders planning activities such as planting and harvest (Table 3). Predictability also pertains to the intensity of rainfall events, with short, intense rains and longer dry periods, or alternation between years with low and high amounts of rainfall (Table 3). Observations about the increasingly unpredictable behaviour of rainfall are almost exclusively located in areas with strong seasonality between latitudes of 30˚N and 30˚S (Fig. 4). These areas have a strong seasonality that now, according to many subsistence-oriented communities, is increasingly unpredictable (according to traditional knowledge systems).

The maps on the left (and on the background on the right) show the (A) Annual Relative Entropy; (B) Annual Rainfall; and (C) DSI (Dimensionless Seasonality Index)2,22 calculated over the period 1955–2005 as decadal trends. Note: Only values around zero indicate no or minor changes. “Match” means that the human observation category “Rainfall - increased variability/changed patterns” matched the direction of the indexes for the plots on the right. Human observations are provided as source data.

Many human observations indicate that rains are delayed and tend to end earlier, leading to a shortening of the rainy season. Shorter rainy seasons are especially reported in Africa, corroborating the large number of human observations of increased drought for this region. These changes in Africa are supported by literature (i.e., refs. 31,37) that also reports that most of the African tropics is experiencing decreasing amounts of rain over increasingly variable periods. Such extended droughts have detrimental consequences for rain-fed agriculture, resulting in food insecurity for many subsistence-oriented communities.

Our results suggest that, in addition to changes in total precipitation, the timing, intensity and distribution of rainfall are of most concern for many communities and critical for their subsistence activities. Thus, developing precipitation indices that document this increased variability also becomes critical. Several researchers have analysed the onset of monsoons or rainy seasons using different methods (e.g., refs. 2,23,35,38,39), but the results and implications are not always consistent or straightforward. While the Dimensionless Seasonality Index can detect changes in the seasonality of rains, it does not determine to what extent a change is significant. An improved and integrated application of this index could result in a better understanding of current and future changes in the seasonality of precipitation, which could be used to plan agricultural practices accordingly (i.e., incorporating crop varieties that tolerate dry sowing or inconsistent rains). However, there are still no analyses, elaborations, or indices built from instrumental data that can solve the unpredictability issue. We recommend that the scientific community focus research on better understanding this increased variability and unpredictability of rainfall, which is already threatening the subsistence activities of thousands of communities globally.

The way forward

This work highlights rainfall changes of major concern for local subsistence-oriented communities. Precipitation changes are difficult to understand at present and harder to project under future greenhouse gas forcing because they are affected by thermodynamic and dynamic effects that are still very uncertain40; in fact, in precipitation projections, model uncertainty is a very relevant factor11. The impacts of these changes are already clear to local communities, but their observations are still largely neglected.

Our data show that local knowledge can offer an additional and robust way of observing climate change (see also18,41,42) providing insights that can inform research in three important ways. First, humans often observe multiple changes in rainfall patterns at one location and often associate changes with other environmental indicators (e.g., prevailing wind direction); as such, their ecological knowledge could aid in designing multifactor indices of rainfall behaviour. Second, our analysis shows that local observations highlight areas where changes are already occurring, but insufficient spatiotemporal coverage by instrument-based data often limits quantification of those changes. Finally, many communities have identified the unpredictability of rainfall as an emerging problem for planning subsistence activities, as also mentioned in the latest IPCC report15. Our work emphasises a need for more applicable precipitation indices describing the seasonality and unpredictability of rainfall, which matters most to thousands of communities around the world. This knowledge could contribute to improving climate services and the use of sub-seasonal to seasonal forecast in agriculture and other sectors43,44.

Methods

This paper combines qualitative and quantitative data on precipitation amounts and distribution. The methods used to gather and analyse those two different types of data are reported below.

Qualitative data

The observations by subsistence-oriented communities were collated between 2012 and 2013 through an extensive review of peer reviewed and grey literature (e.g., scientific articles, project reports, participatory videos)4. The sources used in this article date between 1994 and 2013; however, the documented observations reflect precipitation changes that occurred up to 30-40 years before the interviews reported in the reviewed studies. The age of informants as well as the starting period of the observed change also varied. However, the observations tend to agree about the direction of the observed change for changes that began occurring around the middle of the 20th century. We only considered sources in English or translated into English and only those reporting direct observations by subsistence-oriented communities (e.g., fishers, agro-pastoralists, Inuit, Aymara) that have a close relationship with their environment. We used a variety of keywords such as climate change, traditional ecological knowledge, interviews, observations adding the name of each country in the world (250 including overseas territories). We collated a total of 1017 studies (the complete list is freely available as a Supplementary material in Savo et al.4) that covered multiple observations of climate change (e.g., changes in winds, changes in phenology, changes in floods), and aggregated several categories to examine general trends in the observations (an overview of the full dataset is provided in Savo et al.4). In this paper, we focused only on five detailed categories related to precipitation (Supplementary Table 2). In total, these categories included 3753 observations globally (provided as source data). We did not compare snowfall observations with quantitative indices because of the low number of human observations (253), the limited availability of instrument-based measures of only snowfall, and frequent inclusion of snowfall as a component of total precipitation20.

Although the aim of our paper is not to validate the human observations, we discuss some of the potential biases that could be related to these data. The first-hand observations by subsistence-oriented communities were collected by independent researchers using different interview methods. We only included direct observations by subsistence-oriented people, excluding the information reported by researchers, rangers, or other actors. The observations were gathered in different times of the year through questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, participatory videos etc. (e.g., refs. 45,46). Questions were also different, spanning from generic questions (have you noticed any change in the environment?) to specific questions (have you noted a decrease/increase in rainfall?). However, since our dataset includes observations of diverse changes from a variety of localities across the globe, we believe that our data have significance beyond the diversity of data collection methods and seasons, typology of questions and researchers’ approaches, and culture and gender of the informants4. This is because we found agreement among observations collated by different researchers with different methods in close vicinity, and because in the studies participants could report changes in both directions (e.g., increase or decrease of rainfall). Finally, many researchers have verified the observations in the collated case studies comparing them with local climatic data (e.g., refs. 47,48). For these reasons, we can identify patterns in the observations that are likely to represent actual changes in precipitation amounts and behaviours.

We compiled all data into a single database. Each observation was characterised by the country and locality where the study was based, subsistence activity of the observers, details about the observed change (e.g., “the highest rainfalls used to be in June or July, whereas now, they occur in September”49) and the bibliographic source. Each observation was georeferenced using the name of the locality and the open source Geonames geographical database (http://www.geonames.org) (see also4). For the observations of changes in rainfall patterns, we detailed if communities were noticing an early or delayed start and end of rains as well as changes in duration or predictability of the rainy season.

Quantitative data

We compared the qualitative data to quantitative observations of five different climatic indices (Supplementary Table 1) that were estimated as decadal trends from instrument-based records for a period of 50 years (1955–2005) and subsets of this period (1975–2005 and 1985–2005).

-

(a)

We selected this period because it is consistent with the analyses reported in Savo et al.4 and aligns with the period over which we assumed human observations apply. We recognise that the actual time scale of human observations is not exact, but we note that subsistence-oriented communities generally observed these changes over one-to-two generations4.

-

(b)

The five quantitative climatic indices included: (1) monthly Total Precipitation (TP); (2) extreme precipitation as defined by the annual total precipitation from days > 95 percentile (R95p); (3) drought as defined by Consecutive Dry Days (CDD), or the number of consecutive days where precipitation is less than 1 mm/day; (4) drought as defined by the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), which incorporates measures of precipitation and potential evapotranspiration into a hydrological accounting system; (5) a global measure of the Dimensionless Seasonality Index (DSI), which provides a measure of the seasonal distribution of rainfall, weighted by the normalised mean annual rainfall. Changes in DSI can indicate either a variation in annual rainfall or seasonal differences in rainfall amounts. The Relative Entropy (RE), which is a component of DSI5, provides a measure of the number of wet months and the duration of the rainy season within unimodal rainfall regimes (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 1).

-

(c)

We calculated linear, decadal trends for the five climatic indices listed in Supplementary Table 1 (TP, CDD, PDSI, R95p, DSI) using available datasets at various resolutions (i.e., GHCNDEX, HadEX2, HadEX3). The details and sources of the various datasets are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Most datasets were available at a resolution of 2.5 × 2.5 degrees. Where possible, we used this resolution for consistency and comparability, and we provide as supplementary files the decadal trends at coarser resolutions (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Note that the recent HadEX3 dataset for the CDD and R95p indices was available at a resolution of 1.875 ×1.25 degrees and DSI was available in 0.5 × 0.5 and 1 × 1 degree resolutions (we showed the 0.5 × 0.5 resolution in Fig. 4). Unlike Feng et al.2, we calculated the decadal trend instead of annual changes in the index to remain consistent with our other datasets.

Data analyses

For the instrument-based datasets, we estimated linear decadal trends for sites that contained at least 25 years of data for the period 1955–2005, 15 years of data for the period 1975-2005 and 10 years of data for the period 1985-2005 using the R statistical software package (www.R-project.org) to calculate ordinary least squares regression50. For the HadEX2 dataset we instead estimated linear decadal trends for locations with at least 10 years of data to increase the data coverage; data are only presented in the Supplementary files (i.e., Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Time series are complete for the Dai et al.21 and the GPCC datasets, while for the HadEX3 and GHCNDEX datasets, between 81% to 89% of time series had more than 90% of valid data (source data). After estimating trends for each location with sufficient data, we coded the direction of the trends so that they could be compared with the qualitative data of human observations. Specifically, increasing trends in wetness (or precipitation) were positive, and decreases in wetness (or precipitation) were negative. The magnitudes of the specific trend and their significance were not a priority; we focused instead on the direction of the general trends and their relationship with human observations. Thus, although there is the potential for temporal autocorrelation in the monthly TP data, we did not remove the seasonal cycle because previous research has suggested that the seasonality will not significantly affect the observed direction of the trend (i.e., increasing or decreasing rainfall)51. We performed a Pearson’s chi-squared test with Yates continuity correction52 in R to test whether there was a correlation between rainfall data (TP) and human observations.

We also tested whether there was a change in correspondence between human observations and rainfall data across time (Fig. 3). For each period shown in the three panel Fig. 3, we have:

-

1.

Created a gridbox raster where raster values are the average of all decadal trend values within 10 cells of the original raster cells (horizontally and vertically, and we used the centroid of each grid cell).

-

2.

Compared the sign for the average values obtained with the sign for all human observations that occur within each gridbox to assign “same” or “different” categories to human observations.

-

3.

Created separate rasters for: (a) all human observations, (b) human observations that agree about increased precipitation, c) human observations that agree about decreased precipitation, where the raster values are counts of points that occur inside the gridboxes.

-

4.

Obtained the percentage of agreement about increased or decreased precipitation within each gridbox, dividing human observations that agree about increased precipitation and the total of human observations (b/a from point 3) and dividing human observations that agree about decreased precipitation and the total of human observations (c/a) and we have merged these agreements into one raster.

-

5.

Finally, we have displayed the rasters as coloured gridboxes based on specified bins.

We compared human observations with instrument-based data globally, and then regionally (by Ecozone). We referenced the latitude and longitude of each human observation site with shapefiles documenting the terrestrial ecoregions of the world53 made freely available by the World Wildlife Fund (http://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/terrestrial-ecoregions-of-the-world), overlapping the continent shapes54. For each human observation, we identified the closest available instrumental observation and compared the sign of the climate trend at this location with the sign of the human observation (e.g., increasing precipitation to increasing rainfall). We then recorded if the sign of the trends matched. We performed this comparison for every combination of human observations (Supplementary Table 2) and climatic indices (Supplementary Table 1) available except for DSI for which we only performed a visual comparison. To ensure that human observations were not being compared to geographically irrelevant climate observations, we only analysed the sites where the nearest instrumental observation was within 250 km of the human observation with which it was being compared. To test whether 250 km was too coarse for regions with complex topography or varied microclimates, we also investigated smaller distances (50 km, 100 km). However, these distances resulted in a substantial loss of qualitative data (i.e., observations) not close enough to instrumental observations. Finally, we used different datasets at different resolutions (Supplementary Table 1) to assess if matches and mismatches were possibly affected by the granularity of instrument-based data.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data about people observations are included in this article, in the supplementary information files and as source data. The instrumental observations were downloaded from the websites provided in Supplementary Table 1. Data completeness for the GCHNDEX and HadEX3 datasets (R95p, CDD; 1955–2005) are included as source data. Source data are provided with this paper. Correspondence and requests for other data should be addressed to V.S. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to V.S.

References

Liu, J., Wang, B., Cane, M. A., Yim, S. Y. & Lee, J. Y. 2013. Divergent global precipitation changes induced by natural versus anthropogenic forcing. Nature 493, 656–659 (2013).

Feng, X., Porporato, A. & Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Changes in rainfall seasonality in the tropics. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 811–815 (2013).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I To The Sixth Assessment Report Of The IPCC (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Savo, V. et al. Observations of climate change among subsistence-oriented communities around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 462–473 (2016).

Patz, J. A., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Holloway, T. & Foley, J. A. Impact of regional climate change on human health. Nature 438, 310–317 (2005).

Wheeler, T. & Von Braun, J. Climate change impacts on global food security. Science 341, 508–513 (2013).

Themeßl, M. J., Gobiet, A. & Leuprecht, A. Empirical‐statistical downscaling and error correction of daily precipitation from regional climate models. Int. J. Climatol. 31, 1530–1544 (2011).

Themeßl, M. J., Gobiet, A. & Heinrich, G. Empirical-statistical downscaling and error correction of regional climate models and its impact on the climate change signal. Clim. Change 112, 449–468 (2012).

Rowell, D. P. Sources of uncertainty in future changes in local precipitation. Clim. Dyn. 39, 1929–1950 (2012).

Power, S. B., Delage, F., Colman, R. & Moise, A. Consensus on twenty-first-century rainfall projections in climate models more widespread than previously thought. J. Clim. 25, 3792–3809 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Quantifying the uncertainty sources of future climate projections and narrowing uncertainties with bias correction techniques. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF002963 (2022).

Ensor, J. E. et al. Asking the right questions in adaptation research and practice: Seeing beyond climate impacts in rural Nepal. Environ. Sci. Policy 94, 227–236 (2019).

Nelson, G. C. et al. Agriculture and climate change in global scenarios: why don’t the models agree. Agric. Econ. 45, 85–101 (2014).

Engelbrecht, B. M. et al. Drought sensitivity shapes species distribution patterns in tropical forests. Nature 447, 80–82 (2007).

Pörtner, H. O. et al. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Sillmann, J. K. et al. Combined impacts of climate and air pollution on human health and agricultural productivity. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 093004 (2021).

Reyes‐García, V. et al. Local indicators of climate change: the potential contribution of local knowledge to climate research. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 7, 109–124 (2016).

Ford, J. D. et al. Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 349–353 (2016).

Mistry, J. & Berardi, A. Bridging indigenous and scientific knowledge. Science 352, 274–1275 (2016).

Sillmann, J., Kharin, V. V., Zwiers, F. W., Zhang, X. & Bronaugh, D. Climate extremes indices in the CMIP5 multimodel ensemble: Part 2. Future climate projections. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 2473–2493 (2013).

Dai, A. Characteristics and trends in various forms of the Palmer Drought Severity Index during 1900–2008. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D12115 (2011).

Pascale, S., Lucarini, V., Feng, X., Porporato, A. & ul Hasson, S. Analysis of rainfall seasonality from observations and climate models. Clim. Dyn. 44, 3281–3301 (2015).

Yim, S. Y., Wang, B., Liu, J. & Wu, Z. A comparison of regional monsoon variability using monsoon indices. Clim. Dyn. 43, 1423–1437 (2014).

Hulme, M., Dessai, S., Lorenzoni, I. & Nelson, D. R. Unstable climates: exploring the statistical and social constructions of ‘normal’ climate. Geoforum 40, 197–206 (2009).

Speranza, C. I., Kiteme, B., Ambenje, P., Wiesmann, U. & Makali, S. Indigenous knowledge related to climate variability and change: insights from droughts in semi-arid areas of former Makueni District, Kenya. Clim. Change 100, 295–315 (2010).

Roncoli, C., Ingram, K. & Kirshen, P. Reading the rains: local knowledge and rainfall forecasting in Burkina Faso. Soc. Nat. Resour. 15, 409–427 (2002).

Donat, M. G. et al. Updated analyses of temperature and precipitation extreme indices since the beginning of the twentieth century: the HadEX2 dataset. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 2098–2118 (2013).

Leclerc, C., Mwongera, C., Camberlin, P. & Boyard-Micheau, J. Indigenous past climate knowledge as cultural built-in object and its accuracy. Ecol. Soc. 18, 22 (2013).

Donat, M. G. et al. Global land-based datasets for monitoring climatic extremes. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 94, 997–1006 (2013).

Dunn, R. J. et al. Development of an updated global land in situ‐based data set of temperature and precipitation extremes: HadEX3. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD032263 (2020).

Wainwright, C. M. et al. Eastern African Paradox’ rainfall decline due to shorter not less intense Long Rains. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2, 34 (2019).

Funk, C., Hoell, A., Shukla, S., Husak, G. & Michaelsen, J. in The Monsoons and Climate Change: Observations and Modeling (eds. de Carvalho, L. M. V. & Jones, C.) p. 163-185 (Springer, 2016).

Werth, D. & Avissar, R. The local and global effects of African deforestation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L12704 (2005).

Lau, W. Desert dust and monsoon rain. Nat. Geosci. 7, 255–256 (2014).

Kitoh, A. & Uchiyama, T. Changes in onset and withdrawal of the East Asian summer rainy season by multi-model global warming experiments. J. Meteor. Soc. Jpn 84, 247–258 (2006).

Lebel, T., Diedhiou, A. & Laurent, H. Seasonal cycle and interannual variability of the Sahelian rainfall at hydrological scales. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 8389 (2003).

Dunning, C. M., Black, E. C. & Allan, R. P. The onset and cessation of seasonal rainfall over Africa. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 11405–11424 (2016).

de Carvalho, L. M. V. & Jones, C. The Monsoons and Climate Change: Observations and Modeling (Springer, 2016).

ul Hasson, S., Pascale, S., Lucarini, V. & Böhner, J. Seasonal cycle of precipitation over major river basins in South and Southeast Asia: a review of the CMIP5 climate models data for present climate and future climate projections. Atmos. Res. 180, 42–63 (2016).

Overland, J. E. et al. Nonlinear response of mid-latitude weather to the changing Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 992–999 (2016).

Berkes, F. & Jolly, D. Adapting to climate change: social-ecological resilience in a Canadian western Arctic community. Conserv. Ecol. 5, 18 (2001).

Nakashima, D., McLean, K.G., Thulstrup, H.D., Castillo, A.R. & Rubis, J.T. Weathering Uncertainty: Traditional Knowledge For Climate Change Assessment And Adaptation (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2012).

Stigter, C. J., Dawei, Z., Onyewotu, L. O. Z. & Xurong, M. Using traditional methods and indigenous technologies for coping with climate variability. Clim. Change 70, 255–271 (2005).

Orlov, A., J. Sillmann, J. & Vigo, I. Renewable energy needs better forecasts to handle extreme seasons. Nat. Energy 5, 108–110 (2020).

Ford, J. D., Smit, B., Wandel, J. & MacDonald, J. Vulnerability to climate change in Igloolik, Nunavut: what we can learn from the past and present. Polar Rec. 42, 127–138 (2006).

McNamara, K. E. & Westoby, R. Local knowledge and climate change adaptation on Erub Island, Torres Strait. Local Environ. 16, 887–901 (2011).

McNeeley, S. M. & Shulski, M. D. Anatomy of a closing window: vulnerability to changing seasonality in Interior Alaska. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 464–473 (2011).

Prno, J. et al. Community vulnerability to climate change in the context of other exposure-sensitivities in Kugluktuk, Nunavut. Polar Res. 30, 7363 (2011).

Tschakert, P., Sagoe, R., Ofori-Darko, G. & Codjoe, S. N. Floods in the Sahel: An analysis of anomalies, memory, and anticipatory learning. Clim. Change 103, 471–502 (2010).

Von Storch, H. & Zwiers, F. W. Statistical Analysis in Climate Research (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Pryor, S. C. & Ledolter, J. Addendum to “Wind speed trends over the contiguous United States”. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, D10103 (2010).

Yates, F. Contingency tables involving small numbers and the χ 2 test. Supplement to. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1, 217–235 (1934).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. Bioscience 51, 933–938 (2001).

Environmental Systems Research, Inc. (ESRI). 20020401, World Continents: ESRI Data & Maps (ESRI, 2002).

Liwenga, E. T. Adaptive livelihood strategies for coping with water scarcity in the drylands of central Tanzania. Phys. Chem. Earth 33, 775–779 (2008).

McDowell, J. Z. & Hess, J. J. Accessing adaptation: multiple stressors on livelihoods in the Bolivian highlands under a changing climate. Glob. Environ. Change 22, 342–352 (2012).

Yaro, J. A. The perception of and adaptation to climate variability/change in Ghana by small-scale and commercial farmers. Reg. Environ. Change 13, 1259–1272 (2013).

Shimola, K. & Krishnaveni, M. On a Sustainable Future of the Earth’s Natural Resources (ed. Ramkumar, M.) p. 509–516 (Springer, 2013).

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are due to the Hakai scholars for their suggestions and comments. We are grateful to Domenico Fabio Savo for his help with the R code troubleshooting and to Vidur Mithal for his help with the HadEX3 datasets. V.S. was supported by the Government of Canada/avec l’appui du gouvernement du Canada, the Tula Foundation (Heriot Bay, BC, Canada) through the Hakai Institute (Heriot Bay, BC, Canada) and the Department of Education Science, University Roma Tre. K.E.K. was supported by the NSERC Canada Research Chair programme and NSERC Discovery Grant R832686. J.S. and A.S.H. were supported by the Research Council of Norway grant 244551/E10 (CiXPAG). J.S. further acknowledges funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy - EXC 2037: “CLICCS-Climate, Climatic Change, and Society” - Project Number: 390683824, contribution to the Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN) of Universität Hamburg. C.L.Q. was supported by the UK Royal Society (Grant RP\R1\191063).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both V.S. and K.E.K. conceptualised the research design and contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript. V.S. conducted the bibliographic search and performed the analyses of the ethnographic data. J.S. provided support for the selection of climatic datasets and indices and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. C.M., J.B. and A.S.H. carried out the analyses of climatic data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. C.L.Q. and D.L. contributed to the writing of the manuscript with valuable input.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks James Ford, Katharine Willett and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Savo, V., Kohfeld, K.E., Sillmann, J. et al. Using human observations with instrument-based metrics to understand changing rainfall patterns. Nat Commun 15, 9563 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53861-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53861-7