Abstract

The land sector is anticipated to play an important role in achieving U.S. GHG emissions targets by reducing emissions and increasing sequestration from the atmosphere. This study assesses how much different levels of investment could stimulate land-based mitigation activities in the U.S. By applying a dynamic economic model of the land use sectors, with representation of 26 forestry and agricultural mitigation strategies across 11 U.S. regions, the study shows that annual investments of $2.4 billion could deliver abatement of around 80 MtCO2e annually. Under an optimal allocation of investments, the forestry sector and the Corn Belt are projected to receive the largest share of funds. Restricting land-based activities eligible for funds significantly reduces overall potential mitigation. For instance, if $24 billion investments are allocated only to agricultural activities, mitigation declines by 48% to 54 MtCO2e/yr over the next ten years. Finally, the level of abatement from each policy depends on the timing of implementation as the lowest cost mitigation actions are generally taken by the policy implemented first.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

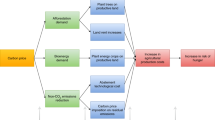

Along with other members of the international community, the U.S. has set ambitious greenhouse gas reduction goals under the Paris Agreement, and all sectors, including the land sector, will play a pivotal role in helping the nation work toward achieving these targets. In the U.S., the land sector (which includes agriculture, forestry, and other land use) is one of the main contributors to both emissions and removals of greenhouse gases (GHG) from the atmosphere. In the most recent U.S. GHG Inventory, it is estimated that about 9.4% of gross U.S. GHG emissions came from agricultural activities for a total of 593.4 Million tons (Mt) of CO2e, while activities in Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) sector represented a net sink, removing about 14.5% of gross emissions in 20231.

Lands have been acknowledged as playing an increasingly important role in U.S. actions to mitigate national GHG emissions and improve carbon sequestration capacity. For instance, the 2021 U.S. Long Term Strategy projects about 1 GtCO2e/yr of net CO2e sequestration from land-based activities is needed to achieve the U.S. 2050 net-zero emissions target2. This goal and interim goals, such as the overall U.S. 2030 target to reduce net GHG emissions by at least 50% compared to 2005 levels, are unlikely to be achieved without specific programs and policies at the local, state, and federal levels targeting emissions reductions and increased carbon sequestration together. Specifically, recent studies show that without policies investing in abatement activities, the land sector could remain a net sink but is expected to increase its net emissions in the near future3,4,5.

In recent years the U.S. has adopted several federal policies to support land-based climate mitigation actions. For instance, the 2022 IRA6, one of the most important pieces of U.S. climate legislation to date, directed investments in the land sector to implement conservation and GHG reduction activities. Specifically, about $24 billion was allotted for investment in agricultural conservation and conservation technical assistance programs between now and 2030 (see Supplementary Table S1). In addition, the U.S. Department of Agriculture is investing over $3.1 billion in 141 selected projects under the Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities program, aiming to sequester 50 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent7. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 provides the Forest Service $5.5 billion and the authority to tackle pressing issues, including increasing wildfire fuel removal, developing national reforestation plans, and encouraging innovation in the wood product industry and bio-based product development8. Finally, the Repairing Existing Public Lands by Adding Necessary Trees (REPLANT) Act supports reforestation efforts on public lands, and pledges to plant 1.2 billion trees and create 49,000 new jobs9.

This policy perspective discusses the potential role of different levels of investments to stimulate mitigation strategies in the U.S. land sector across activities and regions in the next decade. The study employs the domestic land use economic model – the Forestry and Agriculture Sector Optimization Model with Greenhouse Gases (FASOMGHG) – to estimate investment allocation that maximizes GHG mitigation across 26 mitigation activities, 6 in forestry and 20 in agriculture in 11 U.S. regions5.

Currently, the number of studies assessing the projected impacts of recent federal funds on land-based mitigation actions is limited. Bistline et al.10 assessed the effects of IRA funds on key U.S. sectors, including the land sector. Authors show potential mitigation from land-based activities between 0 and 92 MtCO2e/yr in 2030. Coulston et al.11 used a detailed simulation framework to quantify the emissions impact of funding allocation targeting fuel removal and afforestation and found that these investments could reduce the carbon sink of U.S. forests in the near term.

The analysis presented here complements these studies by providing a detailed description of estimated abatement potential in the land sector across activities, GHGs, and regions from different levels of investments.

Instead of examining investments proposed from specific policies and/or for specific activities in the land sector, this paper implements dynamic economic modeling to project the optimal mix of GHG abatement and increased sequestration activities under alternative levels of investments. That is, this study proceeds as though federal funds will be invested in the regions and activities that achieve the highest levels of mitigation potential as a best-case scenario. It is indeed important to note that the optimal implementation of investment policy is not always possible and the scenarios in this analysis are likely to diverge from reality, but they could be used as a benchmark to support policy design.

This analysis also compares this comprehensive all-lands scenario (which includes both forest and agricultural mitigation options) with a scenario in which only agricultural-based activities are eligible for investments, which allows for the estimation of potential tradeoffs of restricting the portfolio of mitigation activities receiving financial support to the agricultural sector. Finally, this study shows how different investment efforts could compete for the same mitigation activities, reducing the potential per dollar invested as lower-cost opportunities are explored first.

Results

Baseline

To evaluate the mitigation potential of investments in the land sector across activities, a baseline scenario is compared to the investment scenarios. In the baseline scenario, no additional mitigation policies (e.g., GHG incentives, state-level renewable standards) are in place, and only market and biophysical conditions drive future land use and land management decisions. Future demand growths for agricultural and forestry commodities are driven by future U.S. population and GDP growth rates from the AEO Reference Case scenario12 (until 2050), and growth rates follow the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) 2 macroeconomic growth rates13 (after 2050) while international trade projections are calibrated to SSP2 growth projections for the rest of the world. This SSP2 scenario is generally considered a middle of the road case, in which macroeconomic trends follow their historical patterns and population and economic growth is moderate through 21003.

Under the baseline scenario, the land use sector is projected to remain a net GHG sink in the next decade, however, at a declining rate. This outcome is driven by land use change activities pursued to meet the growing demand for agricultural commodities. For instance, in 2030 the U.S. agricultural sector is expected to increase its production by 5.6% for major crop commodities and 6.4% for livestock commodities relative to 2020, driving an increase in emissions from 217 to 232 MtCO2e/yr.

The forest sector is projected to reduce its net sink in the baseline over the near-term, falling by 102 MtCO2e/yr in 2030 relative to the present driven by near term harvests as the demand for timber products is projected to increase by 3.8% in 2030 from 2020. Despite this decline in forest sequestration, the Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU) sector overall is projected to have a continued net sink in 2030.

Investment scenarios

To estimate the impact of different investment levels in the next decade on land-based mitigation potential in the U.S., ten investment scenarios are included in FASOMGHG and compared to the baseline case. Investments are modeled in the form of annual payments to landowners and span from a minimum of $90 million to a maximum of $18 billion over the next decade to explore a wide range of alternative mitigation scenarios. Payments are included in the model in the form of GHG price pathways applied to land emissions and subsidies to sequestration activities (All-land investment scenario). Payments start at $5, $20, $35, $50, and $100/tCO2e and grow at annual rates of 1% or 3%. These values are in line with the recent analysis of IRA investments in Bistline et al.11 where the average abatement costs across models range from $27-102/tCO2e. Results presented for the first ten years of the investments are aggregated in three bins according to the cumulative investments (below $10 billion, above $10 billion and below $25 billion, and above $25 billion). After the first ten years investments are supposed to continue following at the same growth rate as the GHG prices.

Finally, to simulate a scenario that sub-selects activities supported by direct investments, the same ten GHG price pathways are applied to only mitigation activities in the agricultural sector (agriculture-only investment scenario). Under this scenario, no other parameters in the model change, but the monetary incentives to reduce GHG emissions are included only for agriculture-based activities, making them relatively less expensive than forest-based activities (e.g., reducing a ton of CO2e via agriculture soil sequestration receives a monetary reward while a reduction via afforestation does not). As a reference, Supplementary Table S3 shows the annual net emissions from AFOLU under the baseline, All-land, and Agriculture-only GHG price pathway scenarios. It is important to note that this scenario analysis focuses on recent investment volumes but does not seek to replicate other parameters of recent policies, meaning the model’s cost optimization function determines mitigation activities and GHG estimates.

All-land investment scenario: mitigation potential

We present the results in form of an investment curve derived from the interpolation of the annual estimates from the economic model. The curve depicts the expected cumulative abatement for the next decade from land-based mitigation activities under cumulative investments level below $50 billion (Fig. 1).

Results show that cumulative investments below $10 billion in forestry and agriculture activities could deliver an average cumulative abatement of 300 MtCO2e in the next decade. For investments between $10 billion and $25 billion, the abatement increases to 680 MtCO2e, and finally, it reaches an average of 1045 MtCO2e per investment higher than $25 billion and below $60 billion in the next ten years. Interestingly, the investment curve exhibits diminishing marginal returns, as doubling the investments does not deliver twice the abatement because the least expensive mitigation activities have already been implemented. For instance, investing $24 billion in the next 10 years could deliver around 800 MtCO2e, but by doubling the cumulative investments to around $48 billion, the cumulative mitigation could only reach around 1180 MtCO2e over the next decade (a 32% increase relative to $24 billion investment). On average, for every $100 invested in land-based activities, around 6 tons of CO2e mitigation could be achieved per these results. After the first decade, assuming the investment pathway continues to grow, the land sector is expected to deliver more mitigation per dollar invested (on average, 12 tons CO2e per $100) as the investment curve becomes less steep and mitigation strategies have more time to deliver their abatement outcomes.

The forestry sector is projected to provide the largest share of abatement across the GHG prices in the All-land scenario, and it is the sector projected to receive the largest share of funding (as funds received by each activity are proportional to the share of abatement delivered). As the level of investment increases, the estimated share of funding allocated to the forestry sector decreases, which indicates that there are more abatement opportunities available in agriculture-based activities under higher incentives and/or that forest-based activities have reached some saturation levels.

Supplementary Table S2 shows that under cumulative investments below $10 billion, on average, almost 80% of abatement comes from forests, while for investments above $10 billion and below $25 billion, the share declines slightly to 70%. For instance, under $24 billion funds, the forestry sector is expected to deliver 56 MtCO2e/yr, agriculture excluding livestock 8 MtCO2e/yr, and livestock 16 MtCO2e/yr of abatement in 2030 with a corresponding $15 billion, $2 billion and $7 billion allocated respectively in the next 10 years. Finally, for investments higher than $25 billion, the average share of forest mitigation declines to 65%, while the share increases for livestock (25%) and agriculture excluding livestock (10%).

Modeled mitigation activities in the forestry sector include reforestation and afforestation, changes in forest management, and changes in timber supply (harvest rates) and production of long-lived wood products. Results show that under the $24 billion investments, changes in forest management (e.g., increase in forest rotation) is the activity estimated to deliver the highest level of mitigation per dollar invested, followed by reforestation and afforestation activities by the end of the decade. Afforestation and reforestation activities like the new National Reforestation Strategy under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 20218, which plans to plant a billion trees across national forests over the next ten years, are also likely to deliver large mitigation potential. Specifically, our results show that a maximum of 30.1 MtCO2/yr could be delivered by this activity in the next decade.

Agricultural-based activities include reduced methane emissions from rice, reduced methane emissions from livestock, and reduced fertilizer applications. Among these activities, the one estimated to deliver the largest mitigation per dollar invested is livestock management through changes in feed mixes and installation of anaerobic digesters with a maximum of mitigation of 34.2 MtCO2e/yr in 2030. Abatement from the agriculture sector could be delivered also by reducing agricultural inputs as recognized by the Conservation Stewardship Program supported by the IRA, and our results show that a maximum of 12.7 MtCO2e/yr of mitigation from agriculture could be achieved by this option in 2030.

By incentivizing land-based mitigation activities, investments might create indirect effects in the market of land commodities5. For instance, results show that the expected production of soybeans, a major input to livestock feed, could decline by up to 5.4% in response to the new investments in land mitigation relative to the baseline.

Mitigation opportunities are available across the three greenhouse gases included in the model assessment. CO2-only mitigation activities are projected to receive the largest share of funding, averaging around 83% of total mitigation. A large portion of CO2 mitigation is sourced by forest-based activities but there are also opportunities in agriculture by increasing carbon sequestered in agriculture soils and reducing on-farm energy usage. The USDA Rural Energy for America Program under the IRA provides an example of investments in CO2-only abatement opportunities from agriculture and our results show that agriculture could deliver up to 7 MtCO2e/yr in the next ten years by reducing energy consumption.

Despite the smaller share, non-CO2 mitigation activities still play an important role in the mitigation portfolio providing low-cost opportunities to reduce N2O and CH4 emissions in the atmosphere. Therefore, funding these activities should continue to be a high priority under federal policies, and the results show that they are also cost-effective. For instance, under investments between $10 billion and $25 billion in the next 10 years, about 36% of the abatement will come from non-CO2 activities, mainly from livestock management. This is an important insight as the U.S. has supported the Global Methane Pledge14, a multilateral agreement to take voluntary actions consistent with a collective effort to reduce global CH4 emissions by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030.

Regional distribution of land-based activities in the All-land scenario

Results also provide an estimated regional distribution of investments in land-based mitigation activities that maximize abatement given a specific level of investments. Using the $24 billion investments as an example for the next decade, Table 1 shows the estimated investment received in each region as allocated between agricultural and forestry activities. The Corn Belt region is estimated to receive the largest share of funds with around $5.3 billion for forestry and agriculture mitigation activities. Abatement is coming mainly from forest management, including extended harvest rotation lengths and an increase in planted forest intensity. Great Plains follows with activities aiming at reducing emissions in manure management through the implementation of anaerobic digesters. The South-Central is expected to receive about 14% of total investments. Forest-based activities in the Lake States region are projected to receive around $ 2.7 billion in the next decade. In the Southeast, under the scenario without investments (baseline), future market conditions will drive additional investments in forests for timber production (relative to the present), leaving few low-cost mitigation opportunities available in the next ten years under-investment scenarios. However, a large share of the investments will flow into livestock-based abatement strategies in the region. The Northeast and the Pacific Northwest are projected to direct investments to efforts that increase forest management and increase forest area.

Finally, in the agriculture sector, investments in mitigating GHGs will drive emissions reduction in manure management through the implementation of anaerobic digesters on farms in the Northeast, reduced inputs application in the Corn Belt, reduced methane emissions from livestock production in the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains through feed mix changes, reduced rice production in the South Central, and implementation of more conservation and no-till practices in the Pacific Northwest.

Abatement potential across multiple policies under the All-land scenario

We use the investment curve to show the conceptual importance of the timing of policy implementation when multiple policies are targeting the same sector and its impact on mitigation volume rendered by a specific program when different investments are considered together (Fig. 2).

Panel A Policy A equal to $3 Billion cumulative investments implemented first (T1) and Policy B equal to $21 Billion investments implemented second (T2). Panel B Policy B equal to $21 Billion investments implemented first (T1) and Policy A equal to $3 Billion cumulative investments implemented second (T2).

By considering two policies (‘Policy A’ financing $3 billion and ‘Policy B’ financing $21 billion) targeting forestry and agriculture mitigation activities, results show cumulative abatement of about 800 MtCO2e in the next decade versus the baseline scenario without investments. The abatement delivered by each policy depends on the time of its implementation. For instance, assuming that Policy A is implemented first (T1), its expected cumulative abatement is 230 MtCO2e, while the abatement for Policy B implemented after (T2) is 570 MtCO2e over the same timeframe (Fig. 2A). In contract, if Policy B is implemented at T1 and Policy A is implemented at T2 they will deliver 745 MtCO2e and 55 MtCO2e respectively (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, this result is similar to the USDA estimates that more than 50 MtCO2e could be avoided over the lives of the SCP projects under investments of $3.1 billion7 (which is in line with Policy A simulated in Fig. 2).

Note that cumulative abatement does not change with average investment of $29 per tons of CO2 abated, but the distribution across policies is affected by the timing. In the case that both policies are implemented simultaneously, this average value could be used to assign abatement delivered by each policy (107MtCO2e per Policy A and 693 MtCO2e per Policy B).

Implications of limiting investments to selected activities: All-land scenario vs Ag-only scenario

As some regulations might target only specific mitigation activities and/or sectors, this section explores the estimated investment dynamics and outcomes if only selected abatement activities receive funding. Specifically, we compare the results of the All-land investment scenario with the Agriculture-only investment scenario, where incentives are only applied to agricultural sector abatement strategies (hence, no crediting forest-based abatement activities).

The expected abatement levels under investments targeting only agriculture are lower than the All-land scenario (Supplementary Fig. S1). For instance, a $24 billion investment in the next 10 years is expected to result in almost 540 MtCO2e cumulative abatement, 48% below the mitigation achieved under the All-land scenario. Ultimately, for the same level of investment, more abatement can be achieved when eligible activities are not restricted, or the same abatement target can be met with fewer investments when more (and cheaper) mitigation options are implemented. Specifically, in an All-land scenario, the investment needed to reach 540 MtCO2e would be around $12 billion, 50% less than the investment needed to achieve the same target in the absence of forestry mitigation options.

When investments target only agriculture mitigation activities, an estimated total of 260 MtCO2e potential abatement is lost compared to the All-land scenario in the next 10 years. This loss can be measured in terms of damage to society by applying the social cost of carbon, a metric that measures the dollar value from damages of emitting an additional ton of CO2 in the atmosphere15. For instance, using a social cost of carbon of 230$/tCO2e16, the damage to society by investing only in agricultural-based mitigation activities is equal to almost $60 billion. Notably, this value is higher than the total investments included in the recent policies for the land sector.

Despite the results showing a net decline in estimated GHG benefits from the investments directed only to agriculture relative to the All-land scenario, some regions will be better off under this case with a larger share of investments directed to their mitigation activities. The changes in the allocation of investments across regions under the two scenarios are driven by different initial land characteristics, current market dynamics, and potential demand for land commodities. For example, the Great Plains and the Southeast are likely to gain from the restricted eligibility of investments to only agriculture-based activities because of more abatement opportunities available in agriculture in these regions than in other regions and in that sector relative to forests per dollar invested. These two regions have large quantities of livestock, which represent the best low-cost mitigation option when forest-based activities are not included in the mitigation portfolio. As a result, the proportion of beef cattle and hogs enrolled in greenhouse gas-reducing manure management systems increases in each of these regions under the Agriculture-only scenario relative to the All-land scenario. Other regions like the Pacific Northwest and the Northeast will likely lose under the Agriculture-only scenario because both regions have limited emissions from agricultural production, and therefore, they find it very expensive to reduce their emissions even with direct monetary support.

Discussion

This analysis presents the best-case scenario of dollars invested in land-based mitigation, as it does not include implementation barriers and risks and the results could therefore be used as a counterfactual to the actual allocation of financial resources to support GHG mitigation in the land sector.

This study finds that the cost-effective composition of land-based activities that can help achieve U.S. GHG mitigation goals includes both forestry and agriculture. Ultimately, both agriculture and forestry activities are necessary to achieve the largest level of abatement per dollar invested in land-related mitigation, and given the synergies and tradeoffs between mitigation activities in the land sector, they should be treated jointly. Moreover, funds should be directed towards both CO2 and non-CO2 mitigation activities as they both present low-cost abatement opportunities. From a societal standpoint focusing only on investments in one sector or set of activities will drive a considerable loss of resources and mitigation potential. For instance, our results found that, on average, achieving the same level of abatement will cost more than twice if only agriculture is targeted.

Despite the limited number of studies on this topic, our estimates fall within the range presented in the literature. For instance, under the 24 billion investments level (which is in line with the IRA funds), this analysis shows about 80 MtCO2e can be achieved annually from U.S. lands, while Bistline et al.10 found a maximum of 90 MtCO2e from the land sector under the IRA investment (Supplementary Fig. S2).

It is noteworthy to mention that this study does not consider co-benefits and potential side effects of these investments on local communities and ecosystems, or other policy goals such as equity and biodiversity preservation. For instance, forest-based mitigation activities might create more ecosystem benefits if implemented in one region relative to another region. As this study estimates only carbon-equivalent benefits, it does not consider other ecosystem services outside forest sequestration that might change the direction or magnitude of investments in each region. Similarly, this analysis does not assess the potential side effects of changes in agriculture practices on local communities in each region.

This study focuses only on direct land-based GHG mitigation opportunities through land management and land use without considering other mitigation activities and policies outside the land sector that are likely to affect land use and land management and indirectly change its GHG balance. As suggested in other studies, bioenergy and mitigation from the land use sector could either complement each other or create additional resource competition when considered conjunctively17. Future research should test the results of this study under alternative investment pathways directed to bio-energy supply. Similarly, this report does not include future demand for land for solar or wind energy production, which is likely to increase under decarbonization scenarios18. Finally, the models do not include demands for non-traditional land-based commodities (e.g., cross-laminated timber or biochar), which might be driven by decarbonization activities outside the land sector and will have effects on emissions fluxes from the land sector.

Lastly, this study does not include potential climate change impacts above those inherent in the underlying data. Other recent studies apply the same model to assess the potential impacts of future climate change19, but those aspects were not included in this analysis. These important considerations are likely to affect the distribution of investments among mitigation categories and across regions and should be addressed in future research.

Methods

Model

This study applies the FASOMGHG model3,5,20,21,22 to assess the impacts of investment aimed at reducing GHG emissions. FASOMGHG is a detailed dynamic intertemporal optimization model of the U.S. forestry and agriculture sectors with representations of regional production processes, land management alternatives, and commodity market feedback on resource systems. The model captures spatial and activity-scale heterogeneity in forestry and agriculture ecosystem characteristics, production costs, and processing. FASOMGHG represents agriculture, forestry, and bioenergy markets within 11 regions, endogenous trade for agricultural commodities (including limited representation of bi-lateral trade with specific regions outside of the U.S), and exogenous trade projections for forest commodities, based on projections presented in Daigneault and Favero23.

The model maximizes the sum of consumer and producer surplus over dynamic intervals for both the forestry and agriculture sectors together. A simplified version of the objective function (OBJ) of the model is presented below:

\({{where\; TGHG}}_{g,t}={\sum}_{r}{{FGHG}}_{r,g,t}+{\sum}_{r}{{AGHG}}_{r,g,t}+{\sum}_{r}{{LGHG}}_{r,g,t}\)

Below we report variables and indexes:

t: time period; g = greenhouse gas (CO2, CH4 and N2O); r = region

i: discount rate by period

\({{FWELF}}_{t}\): annual welfare value for the forest sector

\({{AWELF}}_{t}\): annual welfare value for the agricultural sector

\({{LC}}_{t}\): the cost associated with the linkage between the forest and agricultural sector for land conversion and commodity movement

\(\overline{{{PGHG}}_{t}}\): Exogenous price of GHG emissions ($/ton CO2eq)

\({{TGHG}}_{g,t}\): Total GHG stock

\({{TGHGB}}_{g,t}\): Baseline GHG stock (million tons of CO2eq)

\({{FGHG}}_{r,g,t}\): Forest GHG stock (million metric tons)

\({{AGHG}}_{r,g,t}\): Agriculture GHG stock

\({{LGHG}}_{r,g,t}\): GHG associated with land conversion.

The dynamic nature of the FASOMGHG model yields multi-period equilibrium on a five-year time-step basis over a period of 85 years (from 2015 to 2100), resulting in dynamic simulation of prices, production, consumption, management, and GHG implications in the forest and agriculture sectors. The model solves all time periods at the same time via intertemporal optimization. This commonly used model function allows actors within the model (farmers and timberland managers) to have what is called perfect foresight on expected future environmental, economic, and policy conditions. Intertemporal optimization is an important model attribute, particularly for the forestry sector, as it recognizes that forestry investments are made today with expected returns decades into the future. Furthermore, intertemporal dynamics play a role in agricultural management since the two sectors are linked via competition for land resources, and soil carbon management in agriculture follows a dynamic multi-decadal process.

FASOMGHG represents both privately managed and public timberlands, though public harvest levels are held fixed and exogenously determined, as management decisions regarding public lands are less driven by and responsive to markets than those regarding private lands. Initial data on forest characteristics are from the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) database24, and the forest sector of the model has been recently updated to align with the spatially explicit FIA-based optimization framework LURA - the Land Use and Resource Allocation model3,18,25.

Agricultural land uses represented in the model include cropland, pasture (medium productivity grassland systems that are passively managed), cropland pasture (higher productivity pasture systems that are considered part of the permanent crop rotation), and rangeland (typically lower productivity grassland and rangeland in the Western U.S.). The model allocates land between alternative uses (cropland, forestry, pasture, cropland pasture, and rangeland) to produce primary and secondary agricultural commodities and forest products and to meet biomass demand. Biomass and biofuel demand is currently set exogenously to meet projections from the Annual Energy Outlook (2022) reference scenario for corn ethanol, soybean biodiesel, and woody biomass13.

Comprehensive GHG emissions and carbon sequestration accounting for agriculture, forestry, and other land use is implemented in the model, including carbon stored in above- and below-ground biomass for forests, CO2 emissions from energy intensive input use in agriculture, carbon fluxes related to soil management and land use change, and non-CO2 emissions from crop and livestock production systems.

Baseline and investment scenarios

To estimate the impact of different investment levels in the next decade on land-based mitigation potential in the U.S., a baseline scenario - with no carbon payments for sequestration activities and emissions reduction activities - and ten investment scenarios are included in FASOMGHG. Investments are modeled in the form of annual payments to landowners and span from a minimum of $90 million to a maximum of $18 billion over the next decade to explore a wide range of alternative mitigation scenarios consistent with current policies. Payments are included in the model in the forms of GHG price pathways applied to emissions and subsidies to sequestration activities (\(\overline{{{PGHG}}_{t}}\): in Eq. 1). Payments start at $5, $20, $35, $50, and $100/tCO2e, and they are assumed to grow at different annual rates of 1% and 3%.

In the model investments are not allocated to specific land-based activities but on the land sector in order to present the cost-effective composition of mitigation-activities per dollar invested and provide a guideline on future use of funds that are still not allocated across activities.

Mitigation can be achieved either by reducing emissions or increasing sequestration from the baseline through different activities such as increasing forest areas, decreasing fertilization usage, changing tillage practices, enrolling livestock in manure management systems, etc. Landowners respond to price incentives by implementing activities that reduce GHG emissions up to the point in which reducing an extra ton of CO2e is equal to the exogenous payment. This function leads to landowners implementing the cheapest mitigation activities first and then moving to more expensive ones.

In the model, investments in the form of carbon payments \({{PGHG}}_{t}\) apply to all GHGs from the land sector, ranging from methane in livestock and nitrous oxide from rice production to carbon stored in the soil, and they are received as subsidies when activities to reduce emissions or increase carbon sequestration are implemented. Specifically, the mitigation volume (A) at any time (t) is measured as the difference between GHGs emissions in the baseline scenario without payments (\({{TGHGB}}_{g,t}\)) and emissions estimated in the payment scenario \({{TGHG}}_{g,t}\) across GHG measured in tons of carbon equivalent (tCO2e). For non-CO2 GHGs, note that Carbon Dioxide Equivalence (CO2e) calculations use 100-year Global Warming Potential (GWP) values from IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) to be consistent with the UNFCCC reporting requirements.

Future public investments \(({I}_{t})\) are calculated ex-post by discounting annual expenditures to compensate landowners for their land-based mitigation activities as follows:

where r is the discount rate of 5%, and t0 is the initial year. A similar approach has been used in Austin et al.26. Supplementary Table S3 provides the net emissions from AFOLU under each GHG price scenario under the All-land and Agriculture-only investments framework.

Data availability

The model output data generated by the FASOMGHG model, which was used to visualize the results, have been deposited on the Research Gate repository: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10896.62725.

References

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2021. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA 430-R-23-002. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-andsinks-1990-2021 (2023).

U.S. Department of State & the U.S. Executive Office of the President. The Long-Term Strategy of the United States: Pathways to Net-Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/US-Long-Term-Strategy.pdf (2021).

Wade, C. M. et al. Projecting the impact of socioeconomic and policy factors on greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration potential in U.S. forestry and agriculture. J. For. Econ. 37, 127–161 (2022).

Wear, David N., & John W. Coulston. From sink to source: Regional variation in US forest carbon futures. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16518 (2015).

EPA. Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Potential in the U.S. Forestry and Agriculture Sector. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Atmospheric Protection. Washington DC. EPA. epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-03/epa-430-r-23-004-mitigation-report_full_report_v2.pdf (2024).

USDA. “Inflation Reduction Act”, https://www.usda.gov/ira (2024).

USDA. “Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities Project Selection FAQs”, https://www.usda.gov/climate-solutions/climate-smart-commodities/faqs (2024).

USDA. “Bipartisan Infrastructure Law”, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/about/priorities/bipartisan-infrastructure-law (2024).

U.S. Senators Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) & Rob Portman (R-Ohio), U.S. Representatives Jimmy Panetta (CA-20) & Mike Simpson (ID-2). “The REPLANT Act of 2021” https://www.agriculture.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/REPLANT%20Factsheet.pdf (2024).

Bistline, John et al. Emissions and energy impacts of the Inflation Reduction Act. Science 380, 1324–1327 (2023).

Coulston, J. W., Domke, G. M., Walker, D. M., Brooks, E. B. & O’Dea, C. B. Near-term investments in forest management support long-term carbon sequestration capacity in forests of the United States. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad345 (2023).

EIA. Annual Energy Outlook 2022. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/ (2022).

Riahi, K. et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168 (2017).

The White House. Joint US-EU press release on the Global Methane Pledge. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/18/joint-useu-press-release-on-the-global-methane-pledge/ (2021).

Nordhaus, W. D. Revisiting the social cost of carbon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1518–1523 (2017).

U.S. EPA. Supplementary Material for the Regulatory Impact Analysis for the Final Rulemaking, “Standards of Performance for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources and Emissions Guidelines for Existing Sources: Oil and Natural Gas Sector Climate Review”: EPA Report on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases: Estimates Incorporating Recent Scientific Advances. Washington, DC: U.S. EPA. (2023).

Favero, A., Daigneault, A. & Sohngen, B. Forests: Carbon sequestration, biomass energy, or both? Sci. Adv. 6, eaay6792 (2020).

Van de Ven, D. J. et al. The potential land requirements and related land use change emissions of solar energy. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–12. (2021).

Baker, J. S. et al. Projecting U.S. forest management, market, and carbon sequestration responses to a high-impact climate scenario. For. Policy Econ. 147, 1–17 (2023).

Adams, D. et al. FASOMGHG conceptual structure, and specification: Documentation. Unpublished paper. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University, Department of Agricultural Economics. (2005).

Adams, D. M., Alig, R., McCarl, B., Callaway, M. & Winnett, S. The Forest and Agricultural Sector Optimization Model (FASOM): model structure and policy applications. Res. Paper PNW-RP-495. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland. (1996).

McCarl, B. A. & Spreen, T. H. Price endogenous mathematical programming as a tool for sector analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 62, 87–102 (1980).

Daigneault, A. & Favero, A. Global forest management, carbon sequestration and bioenergy supply under alternative shared socioeconomic pathways. Land Use Policy 103, 105302 (2021).

Jones, J. P. H. et al. The importance of cross-sector dynamics when projecting forest carbon across alternative socioeconomic futures. J. For. Econ. 34, 2015–231. (2019).

Latta, GregoryS., Justin, S. Baker & Ohrel, Sara A land use and resource allocation (LURA) modeling system for projecting localized forest CO2 effects of alternative macroeconomic futures. For. Policy Econ. 87, 35–48 (2018).

Austin, K. et al. The economic costs of planting, preserving, and managing the world’s forests to mitigate climate change. Nat. Commun. 1, 1–9 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (Contract #68HERH19D0030, Call Order #68HERH23F0146) (A.F., C.W., Y.C., and J.B.). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F., C.W., S.O., J.B., and J.C. conceptualized and designed the study. C.W., Y.C., G.L., and B.M. curated data, supported model development, and ran the model. A.F., C.W., S.O., J.B., J.C., and S.R. wrote the original draft and reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.F. and C.W. created visualizations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Favero, A., Wade, C.M., Cai, Y. et al. US land sector mitigation investments and emissions implications. Nat Commun 15, 9625 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53915-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53915-w

This article is cited by

-

Investing in U.S. forests to mitigate climate change

Carbon Balance and Management (2025)